Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 129.219.247.33 On Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

Uploaded by

shamOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 129.219.247.33 On Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

Uploaded by

shamCopyright:

Available Formats

The Blood of Christ in the Later Middle Ages

Author(s): Caroline Walker Bynum

Source: Church History , Dec., 2002, Vol. 71, No. 4 (Dec., 2002), pp. 685-714

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of Church

History

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4146189

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4146189?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Church History

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Blood of Christ in the Later

Middle Ages'

CAROLINE WALKER BYNUM

In one of our earliest descriptions of meditation on the crucifix, Aelred

of Rievaulx (d.1166) described the body on the cross, pierced by the

soldier's lance, as food and urged the female recluses for whom he wrote

not only to contemplate it but also to eat it in gladness: "Hasten, linger

not, eat the honeycomb with your honey, drink your wine with your

milk. The blood is changed into wine to inebriate you, the water into milk

to nourish you."2 Marsha Dutton, who has written so movingly of

Cistercian piety, speaks of this as a eucharistic interpretation of the literal,

physical reality of the crucifixion and points to the parallel with Berengar

of Tours' oath at the synod of Rome in 1079: "The bread and wine which

are placed on the altar.., .are changed substantially into the true and

proper vivifying body and blood of Jesus Christ our Lord and after the

consecration there are the true body of Christ which was born of the

virgin... and the true blood of Christ which flowed from his side... in

their real nature and true substance."3

1. I worked on this paper in the spring of 2000 when I was Aby Warburg Visiting Professor

at the Warburg Haus in Hamburg; I am grateful to the staff there for assistance. An

earlier version was given as a talk at the New England Medieval Conference at Yale

University in October, 2000. For helpful comments, I thank my host, Paul Freedman,

and the conference participants, especially Frederick Paxton. Portions of sections 3-5

appeared in different form in German as "Das Blut und die Korper Christi im spiten

Mittelalter: Eine Asymmetrie," Vortriige aus dem Warburg-Haus 5 (2001): 75-119. I am

grateful to Guenther Roth, Dorothea von Miicke, and two anonymous readers for

Church History for many valuable suggestions.

2. Aelred of Rievaulx, De institutione inclusarum, c. 31, in Aelred, Opera omnia, vol. 1, ed. A.

Hoste and C. H. Talbot, Corpus christianorum: continuatio medievalis 1 (Turnhout:

Brepols, 1971), 671; trans. M. P. Macpherson, "Rule of Life for a Recluse," in The Works

of Aelred of Rievaulx 1: Treatises and Pastoral Prayer, Cistercian Fathers Series 2 (Spencer,

Mass.: Cistercian Publications, 1971), 90. And see Marsha Dutton, "Eat, Drink, and Be

Merry: The Eucharistic Spirituality of the Cistercian Fathers," in Erudition at God's

Service, ed. John R. Sommerfeldt, Studies in Medieval Cistercian History 11 (Kalamazoo,

Mich.: Cistercian Publications, 1987), 9, and Caroline Walker Bynum, Jesus as Mother:

Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1982), 122-24.

3. Dutton, "Eat, Drink and Be Merry," 29, n. 28, quoting Berengar from Gary Macy, The

Theologies of the Eucharist in the Early Scholastic Period: A Study of the Salvific Function of the

Sacrament According to the Theologians, c. 1080-c. 1220 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1984), 37.

Caroline Walker Bynum is University Professor at Columbia University in the City

of New York.

? 2002, The American Society of Church History

Church History 71:4 (December 2002)

685

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

686 CHURCH HISTORY

Dutton's interpreta

standard one. Inde

eucharistic references in medieval devotional literature wherever eat-

ing and drinking, bread and wine, body and blood, occur.4 Some

work in literary studies has been inclined to take eucharistic change as

the semiotics of early modern Europe. (In a book recently published

on the "new historicism," eucharist becomes a way of thinking about

everything.)5 And some art historians have used the rise of ocular

communion or Augenkommunion (the idea that one receives the eu-

charist by viewing the consecrated host) as their central evidence for

the visuality of late medieval culture." Recent work seems to find the

eucharist everywhere.

4. On the eucharist, see Macy, Theologies of the Eucharist; David Burr, Eucharistic Presence

and Conversion in Late Thirteenth-Century Franciscan Thought, Transactions of the Amer-

ican Philosophical Society 74.3 (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society,

1984); Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food

to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987); Miri Rubin, Corpus

Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1991); Charles Caspers, Gerard Lukken, and Gerard Rouwhorst, eds., Bread of Heaven:

Customs and Practices Surrounding Holy Communion: Essays in the History of Liturgy and

Culture (Kampen, Netherlands: Kok Pharos, 1995); and Andre Haquin, ed., Fete-Dieu

(1246-1996) 1. Actes du Colloque de Liege, 12-14 Septembre 1996, Universite catholique de

Louvain: Publications de l'Institut d'Etudes Medievales (Louvain-la-Neuve: College

Erasme, 1999).

5. Catherine Gallagher and Stephen Greenblatt, Practicing New Historicism (Chicago: Uni-

versity of Chicago Press, 2000).

6. On visuality or "Schaufrdmmigkeit," see Uwe Westfehling, Die Messe Gregors des

Grossen: Vision, Kunst, Realitdt: Katalog und Fiihrer zu einer Ausstellung im Schniitgen-

Museum der Stadt Kiln (Cologne: Wienand, 1982), esp. 37; Robert Scribner, "Vom

Sakralbild zur sinnlichen Schau," in Klaus Schreiner and Norbert Schnitzler, eds.,

Gepeinigt, begehrt, vergessen: Symbolik und Sozialbezug des Kdrpers im spditen Mittelalter und

derfriihen Neuzeit (Munich: Fink, 1992), 309-336; Anton Legner, Reliquien in Kunst und

Kult zwischen Antike und Aufkldrung (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft,

1995), 256-77; Judith Oliver, "Image et devotion: le r61le de l'art dans l'institution de la

Fete-Dieu," in Haquin, ed., Fite-Dieu, 153-72; and Bruno Reudenbach, "Der Altar als

Bildort: Das Fluigelretabel und die liturgische Inszenierung des Kirchenjahres," in

Goldgrund und Himmelslicht: Die Kunst des Mittelalters in Hamburg (Hamburg: Stiftung

Denkmalpflege: Dolling und Galitz, 1999), 26-33. For intelligent caveats about this, see

Paul Binski, "The English Parish Church and Its Art in the Later Middle Ages: A Review

of the Problem," Studies in Iconography 20 (1999): 1-25, esp. 13-14, who agrees with me

about recent overemphasis on the eucharist.

On the rise of spiritual communion, see Jules Corblet, Histoire dogmatique, liturgique et

archeologique du sacrement de l'eucharistie, 2 vols. (Paris: Societe Generale de Librairie

Catholique, 1885-86); Edouard Dumoutet, Le Desir de voir l'hostie et les origines de la

devotion au Saint-Sacrement (Paris: Beauchesne, 1926); Dumoutet, Corpus Domini: Aux

sources de la piete eucharistique medievale (Paris: Beauchesne, 1942); Peter Browe, Die

Verehrung der Eucharistie im Mittelalter (Munich: Hueber, 1933); F. Baix and C. Lambot,

La Devotion a' la eucharistie et le VIIle centenaire de la Fete-Dieu (Gembloux: Duculot, 1964);

Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast, 31-69; Rubin, Corpus Christi, 35-82; and Charles

Caspers, "The Western Church During the Late Middle Ages: Augenkommunion or

Popular Mysticism?," in Bread of Heaven, ed. Caspers et al., 83-98.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 687

But, if we turn again

thing odd. Aelred does

that blood changes to w

the blood from Christ's

Moreover, no change is

comb," writes Aelred,

told that the flesh beco

the side become milk a

recluse is urged to enter

drink there the preciou

ering up "the drops o

then, in Aelred's meditat

on blood more than o

change (blood to wine)

blood); and third, an im

on grains pulled togeth

but on blood that spills i

body.

There is, in other words, in this imagery, an asymmetry between the

body and blood that may at first escape our attention. To Aelred and

his Cistercian contemporaries, indeed in twelfth-century piety gener-

ally, the food of Christ, whether honeycomb or bread, is food and

overwhelmingly an image of union and community, of members like

grains of wheat gathered into Ecclesia.7 But the blood is blood, changed

into wine to hide the horror of sacrifice,8 a complex image of violence

7. Macy, Theologies of the Eucharist, sees the ecclesiological interpretation of the eucha-

rist as dominant from about the middle of the twelfth century on. For an example of

the eucharistic elements as symbols of the pious gathered into one church, see

Rupert of Deutz, Commentaria in Joannem, bk. 6, sect. 206, in J.-P. Migne, ed.,

Patrologiae cursus completus: series latina, 221 vols. (Paris; Migne, 1841-64) [hereafter

PL] vol. 169, cols. 468-69 and 483D-484A. Macy tends, however, to underestimate

the element of sacrifice, which remained crucial in eucharistic devotion and theol-

ogy; see Jaroslav Pelikan, The Growth of Medieval Theology (600-1300), vol. 3 of The

Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine (Chicago: The University

of Chicago Press, 1978), 129-44 and 184-204, and P. J. Fitzpatrick, "On Eucharistic

Sacrifice in the Middle Ages," in Sacrifice and Redemption: Durham Essays in Theology,

ed. S.W. Sykes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 129-56.

8. As Dutton points out, the argument that the eucharist should be veiled because of

its horror was traditional and went back to Ambrose; see Dutton, "Eat, Drink and Be

Merry," 9-10. See also Macy, Theologies of the Eucharist, 28-51, 72 and 108; Pelikan,

Growth of Medieval Theology, 199; Rubin, Corpus Christi, 91 n. 56; Brian Stock, The

Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and

Twelfth Centuries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), 290-91; and Klaus

Berg, "Der Traktat des Gerhard von K61n iiber das kostbarste Blut Christi aus dem

Jahre 1280," in 900 Jahre Heilig-Blut-Verehrung in Weingarten 1094-1994: Festschrift

zum Heilig-Blut-Jubillium am 12. Miirz 1994, ed. Norbert Kruse and Hans Ulrich

Rudolf, 3 vols. (Sigmaringen: Thorbeke, 1994), vol. 1, 442, 449-50. As Roger Bacon,

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

688 CHURCH HISTORY

and division as well

even ecstasy. What

sions on the para

devotional literatur

competition. In this

this asymmetry. Fir

to a factor that has

the existence of a n

ond, I want to expl

symbols themselves

I. EUCHARISTIC BACKGROUND

There are many reasons for this disjunction or asymmetry be-

tween body and blood, and some lie in liturgical and theologi

developments concerning the eucharist itself. Work done over th

past fifty years has revealed to us the complicated process by wh

university theologians and preachers attempted to focus the atte

tion of the faithful on the host."1 As the cup was withdrawn fro

the laity, ostensibly for disciplinary reasons (the fear of spillag

the doctrine of concomitance was employed to explain that t

whole Christ (totus Christus) was present in each of the two ele-

ments and in every fragment.1" Moreover, despite the legal r

quirement of at least yearly communion (actual partaking of the

eucharistic elements), reception with the eyes at the moment

consecration or elevation (so-called ocular or spiritual communion

became for many the focal point of eucharistic devotion. Th

The Opus maius of Roger Bacon, tr. Robert Belle Burke, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Th

University of Pennsylvania Press, 1928), vol. 2, 822, expressed it: "[If the body a

blood were visible,] we could not sustain it from horror and loathing. For the huma

heart could not endure to masticate and devour raw and living flesh and to drin

fresh blood. And therefore the infinite goodness of God is shown in veiling th

sacrament."

9. Since I wrote this paper, an excellent full-length study of the blood relic at Westmi

has appeared: Nicholas Vincent, The Holy Blood: King Henry III and the Westminster B

Relic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). Vincent's study focuses on w

the relic at Westminster did not give rise to a cult. Although it attempts to pu

English phenomenon in a European context, it has little about blood cult in Germa

in which I have been particularly interested in this paper.

10. See n. 6 above.

11. James J. Megivern, Concomitance and Communion: A Study in Eucharistic Doctrin

Practice, Studia Friburgensia, n.s. 33 (Fribourg, Switzerland: University Press, 1963

Megivern points out, the old argument that the doctrine of concomitance was devel

to justify the withdrawal of the cup is untenable. The roots of the idea are in

medieval efforts to refute the notion that receiving communion divides Christ

pieces.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 689

liturgy increasingly em

of Corpus Christi dev

Blood and was much

never attained the ritu

miracles of the chalice

Nonetheless, blood fren

have discussed elsewhe

were denied access to th

flooding of ecstasy throu

mouths as blood.13 Cath

in her mouth or pourin

host.14 The priest John

crucified Christ bleeding

replaced by the form of

the sacrament, "totally

denly, in a miraculous m

Lord Jesus Christ, whom

uous rushing river thr

12. Peter Browe, Die Eucharisti

rischen Theologie, NF 4 (Bresl

vol. 1, 447-515; Caroline Wal

the Thirteenth Century," Wo

Heilig-Blut-Verehrung im Ub

(1094-1803)" in 900 Jahre Hei

"Der bleibende Gehalt der He

1, 382.

13. See Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast; Reginald Gr6goire, "Sang," Dictionnaire de

spiritualitd, ascetique et mystique, doctrine et histoire, ed. M. Viller et al., vol. 14 (Paris:

Beauchesne, 1990), cols. 324-33; Rubin, Corpus Christi, especially chapters 2 and 5;

Peter Dinzelbacher, "Das Blut Christi in der Religiositait des Mittelalters," in 900

Jahre Heilig-Blut-Verehrung, vol. 1, 415-434; and Danible Alexandre-Bidon, "La d&-

votion au sang du Christ chez les femmes medievales: des mystiques aux laiques

(XIIIle - XVIe siecle)," in Le Sang au moyen age: Actes du quatrihme colloque international

de Montpellier, Universite Paul Valery (27-29 novembre 1997), ed. Marcel Faure

(Montpellier: Universite Paul Valery, 1999), 405-13. Dinzelbacher maintains that the

substitution of blood for communion wine in visions was fairly infrequent ("Das

Blut Christi," 425).

14. Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast, 177; on Catherine's blood mysticism generally, see

ibid., 174-79, and Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz, "'Die Braut auf dem Bett von Blut und

Feuer': Zur Bluttheologie der Caterina von Siena (1347-1380)," in 900 Jahre Heilig-Blut-

Verehrung, vol. 1, 494-500.

15. Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast, 399, n. 49. See also ibid., 62, n. 128, for Mechtild of

Hackeborn (d. ca. 1298) who received Christ's heart "in the form of a cup" contain-

ing "the drink of life" at "the hour of communion." On the blood mysticism (with

strong eucharistic overtones) of the Helfta nuns generally, see Bynum, Jesus as

Mother, chapter 5.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

690 CHURCH HISTORY

intimate parts of he

wafer, she experienc

Symbolically speak

breached, threaten

streets in the new f

round white whole

menaced by Jews, in

story, it dripped m

trine of real presen

those who violated

it, Jews who desecra

of God.17 When Geo

heresy in 1525, saw

it to hold in the b

much medieval dev

one hand, bread-bo

munity, and, on th

sacrifice, reproach.1

16. "Les 'Vitae Sororum

liotheque de Colmar," ed.

raire du moyen age 5 (19

spirituelle Theologie: zu M

seiner Zeit (Munich: Art

Visionary (New York: Zon

drawing of St. Bernard a

has drawn our attention, shows such inundation. The fact that the nun's hands are

over the gushing flood may suggest that the adherent is still at some distance from

immersion-union, but it may also suggest that access to the Christ of blood and suffering

is through touch, grasping, physical encounter. See Jeffrey F. Hamburger, Nuns as

Artists: The Visual Culture of a Medieval Convent (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1997), plate 1. There is, in this period, a strong devotional emphasis on touching as well

as seeing the precious blood-an emphasis found especially in the references (both

visual and textual) to Thomas putting his hand into Christ's side and touching his heart;

see Horst Appuhn, "Sankt Thomas," Kunst in Hessen und am Mittelrhein 5 (1966): 7-10,

and "Der Auferstandene und das Heilige Blut zu Wienhausen: Ober Kult und Kunst im

spiten Mittelalter," Niederdeutsche Beitriige zur Kunstgeschichte 1 (1961): 90-94.

17. See the works cited in n. 77 below. For a number of examples of objects that accuse and

threaten by bleeding, see Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast, 329 nn. 135 and 138. Medieval

writers occasionally understood unworthy reception as itself killing Christ; see, for

example, Gerald of Wales, Gemma ecclesiastica, c. 50, in Giraldi Cambrensis Opera, ed. J. S.

Brewer, J. F. Dimock, and G. F. Warner, 8 vols., Rerum Britannicarum medii aevi scrip-

tores, 21 (London: Longman, 1861-91; Kraus reprint, 1964-66), vol. 2, 139. I owe this

reference to an anonymous reader for Church History.

18. Edward Peacock, "Extracts from Lincoln Episcopal Visitations in the 15th, 16th, and 17th

Centuries," Archaeologia: or Miscellaneous Tracts relating to Antiquity 48 (London: The

Society of Antiquaries, 1885), 251-53, and see Rubin, Corpus Christi, 344-45.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 691

II. BLOOD RELICS

Body/blood asymmetry is then profoundly eucharistic. But

reasons for the asymmetry lie beyond eucharist as well. There i

obvious element we have tended to overlook because of our recent

concentration on eucharistic devotion-that is, a second blood tradi-

tion in medieval Europe, the devotion to the blood relics of Christ. The

first point I wish to make in this essay, then, is that the two traditions,

that of blood relic and that of eucharistic blood, influenced each other

profoundly, crossing and recrossing in the course of the Middle Ages.

Theological discussions of concomitance inflected discussions of

blood relic, providing a defense against skeptical objections to its

historicity;19 eucharistic practices influenced its cult, so much so that

we find, by the late-thirteenth century, a sort of quasi-eucharistic rite

of drinking the blood of the relic (rather like the use of the ablutions

cup after Mass).20 Similarly, traditions concerning the collecting and

revering of Christ's blood as relic undergirded and encouraged the

stress in eucharistic devotion on blood as sacrifice, violation and

access-pulled the eucharist, so to speak, away from Last Supper and

toward crucifixion.21 Some of the rather puzzling devotional asym-

metry I mentioned earlier has roots in the fact that there were in the

European tradition, to put it simply, two bloods and one body.22

And the bloods could compete. In a poem composed for the abbey

of F&camp just at the time Aelred was writing his meditation on the

crucifix, pilgrims were urged to behold the relic of precious blood

"not as you do in the sacrament" but just as it flowed from the Savior's

19. For two examples, see n. 56 below.

20. Wine or water was poured over the relic and drunk; see Rainer Jensch, "Die Weingar-

tener Heilig-Blut- und Stiftertradition: Ein Bilderkreis kl6sterlicher Selbstdarstellung"

(Diss. Phil., Tuibingen, 1996), 23-24, and Adalbert Nagel, "Das Heilige Blut Christi," in

Festschrift zur 900-Feier des Klosters: 1056-1956 (Weingarten, 1956), 201-03. Edmund Rich

of Abingdon (d. 1240), archbishop of Canterbury, washed the wounds of a crucifix with

wine and then drank it; see Louis Gougaud, Devotions et pratiques ascetiques du moyen age

(Paris: Descle6, de Brouwer, 1925), 77-78. On the general relationship between eucharist

and relic, see Godefridus J. C. Snoek, Medieval Piety from Relics to the Eucharist: A Mutual

Relationship (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1995).

21. There are, however, a few Holy Blood altars that relate the blood closely to the Last

Supper; see Barbara Welzel, Abendmahlsaltdire vor der Reformation (Berlin: Gebr. Mann

Verlag, 1991), 24, 26, and 116-31. It is important to note that such depictions of the Last

Supper are usually of the moment of Judas's betrayal, not of the consecration.

22. The devotion to Christ's foreskin was, in a sense, a body-devotion parallel to the

devotion to blood relics. But it was far rarer. See Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast, 377 n.

135. Charroux provides an example of devotion to parallel bodily relics of foreskin and

blood from the circumcision: see X. Barbier de Montault, Oeuvres complates, vol. 7: Rome,

part 5.2 (Paris: Vives, 1893), 528.

23. Dinzelbacher, "Das Blut Christi," 415.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

692 CHURCH HISTORY

side when he died fo

passage "demonstrat

of Christ was a for

seems, however, to h

itly competed with

Fecamp poet, who say

not veiled by specie

("en sa fourme propr

to save the world.

To make clear the complex relationship between eucharist an

blood relics, I wish to sketch the history of these relics and then t

examine a little-known thirteenth-century polemical treatise by on

Gerhard of Cologne that demonstrates the ways in which the theology

of the blood of Christ competed with, absorbed, and influenced eu

charistic theology and imagery.26

Our earliest reference to a relic of the blood Christ shed at the

Passion may be in a letter from Braulio of Saragossa about 649, w

expressed concern that such veneration might overshadow the m

Blood relics proliferated in the west in the Carolingian period not lo

before theologians such as Paschasius Radbertus and Ratramnus

gan to discuss the Eucharist. Holy blood was supposedly discove

at Mantua in 804 in Charlemagne's presence. Its fate is unknown,

another vial, found in the mid-eleventh century, became the center

an important cult and was later claimed to be the source of the fam

relic at the German cloister of Weingarten near Ravensburg. T

oldest surviving western blood relic is probably the cros

Reichenau, supposedly acquired in 925 from the countess Swanah

24. "Non pas comment u Sacrement/Mes en sa fourme proprement/Vermel comment

sengna/Quant pour nous mort soufrir dengna." In Oskari Kajava, ed., Etudes sur d

pokmes franpais relatifs a' l'abbaye de Fecamp (Helsinki: Sociat6 de Litterature Finn

1928), 95.

25. Jonathan Sumption, Pilgrimage: An Image of Medieval Religion (Totowa, N.J.: Rowman

and Littlefield, 1975), 48. The competition is all the more interesting in light of the fact

that the cult at Fecamp appears to have originated in a eucharistic miracle that was later

re-figured as a blood relic; see Vincent, Holy Blood, 57-58.

26. On blood relics generally, see Barbier de Montault, Oeuvres completes, vol. 7, 524-37;

Johannes Heuser, "'Heilig-Blut' in Kult und Brauchtum des deutschen Kulturraumes.

Ein Beitrag zur religiosen Volkskunde" (Diss. Phil., Bonn, 1948); Nagel, "Das Heilige

Blut Christi," 197-98; Sumption, Pilgrimage, 44-49 and 312; Thomas Stump and Otto

Gillen, "Heilig-Blut," in Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunst-Geschichte, ed. Otto Schmitt, vol.

2 (Stuttgart: Alfred Druckenmiiller, 1948) [hereafter RDK], cols. 947-58; R. Haubst, "Blut

Christi," R. Bauerreiss, "Bluthostien," A. Winklhofer, "Blutwunder," in Lexikon fir

Theologie und Kirche, ed. Josef H6fer and Karl Rahner, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Freiburg: Herder,

1958) [hereafter LTK], cols. 544-49; and Vincent, Holy Blood, 31-81 (see 51-52 n. 76 for

more bibliography).

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 693

who had received it fr

then streamed into Eur

many, after the First C

Bruges only a little later

blood for Westminster

elevating the claims of

(since Louis had only

is ... holy... on account

made upon it, not the bl

Indeed relics often expre

in Henry III's gift to W

Hapsburg acquired for

relic of the holy blood

and was clearly intende

bor Weingarten suppos

Not all blood relics in th

however, derived in th

disputed bleeding host

spilled chalices. (Thes

fraudulent-that Marg

see.)32 And blood could

27. On Braulio, see Caroline Wa

tianity, 200-1336 (New York

early cult, see Jensch, "Die

30-31; Nagel, "Das Heilige B

Ojberblick;" Helmut Binder, "

Verehrung, vol. 1, 337-47, an

ibid., 331-36.

28. Stump and Gillen, "Heilig-

und Stiftertradition," 31.

29. Jacques Toussaert, Le sentim

1963), 259-67. Although obtai

receive regular processions un

explosion of miracles and dev

30. Matthew Paris, Chronica

Britannicarum medii aevi sc

and vol. 5, 29, 48, and 195;

Iconography of the Thirteent

in England in the Thirteenth

W. M. Ormrod (Woodbridge

Vincent, Holy Blood.

31. Jensch, "Die Weingartener

Blut," 197; and Binder, "Das

Verehrung, vol. 1, 348-58. Not

was also patron of Weingarte

32. The Book of Margery Kemp

Bowdon, ed. S. B. Meech wit

Oxford University Press for

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

694 CHURCH HISTORY

images-crucifixes, a

ple, the cathedral at

supposedly went bac

by Jews, out of whi

greatly revered.33

Although modern a

from blood relics and to sort out three distinct sources of the blood

revered in late medieval cult,34 it is clear that adherents often care

little on which traditions the relics drew. We do not know, for exam-

ple, what kind of blood the relic revered at Cloister Wienhausen wa

despite the convent's pride in it, indulgences connected to it, and

stories in the surviving chronicle of the miracles it worked.35 Th

source was not important to the nuns: Christ's blood was Christ's

blood.

Indeed, in this conflation of types of blood, we see one of the most

sinister aspects of blood-cult. Whether Christ himself, the consecrated

host, or a devotional object, the victim is increasingly in the years

Wunder, 166-71; Jensch, "Die Weingartener Heilig-Blut- und Stiftertradition," 37-39;

Hartmut Boockmann, "Der Streit um das Wilsnacker Blut: zur Situation des deutschen

Klerus in der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts," Zeitschrift fiir historische Forschung 9 (1982):

385-408; Charles Zika, "Hosts, Processions and Pilgrimages: Controlling the Sacred in

Fifteenth-Century Germany," Past and Present 118 (1988): 25-64; and Hartmut Kiihne,

"'Ich ging durch Feuer und Wasser....' Bemerkungen zur Wilnacker Heilig-Blut-

Legende," in Gerlinde Strohmaier-Wiederanders, ed., Theologie und Kultur: Geschichten

einer Wechselbeziehung: Festschrift zum einhundertfiinfzigjaihrigen Bestehen des Lehrstuhls fiir

Christliche Archiiologie und Kirchliche Kunst an der Humboldt-Universitiit zu Berlin (Halle:

Andre Gursky, 1999), 51-84. On frauds generally, see Franti~ek Graus, "Fdilschungen im

Gewand der Fr6mmigkeit," in Fdilschungen im Mittelalter: Internationaler Kongress der

Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Miinchen, 16.-19. September 1986, 5 vols. (Hannover:

Hahn, 1988), vol. 5, 261-80. It is significant that the goal of pilgrimage at Wilsnack was

known at the time as the "blood of Christ," although the objects revered were wonder-

hosts.

33. Stump and Gillen, "Heilig-Blut," col. 956, figure 7; M.-D. Chenu, "Sang du Christ," in

Dictionnaire de theologie catholique, ed. A. Vacant, E. Mangenot, and E. Amann, vol. 14

(Paris: Letouzey et And, 1939), col. 1094-97; Jensch, "Die Weingartener Heilig-Blut- und

Stiftertradition," 31. In the fifteenth century, Nicolas V (wrongly) attributed the story to

a sermon of Athanasius cited at II Nicaea (787). In the eleventh century, Siegebert of

Gembloux tells the miracle of Beirut under the year 765, and it was often celebrated in

the high Middle Ages; the Roman martyrology mentions it for November 9.

34. See, for example, the articles from LTK cited in n. 26 above, which strain to divide the

surviving stories into categories according to the source of the blood.

35. The seventeenth-century chronicle from Wienhausen, which draws on earlier traditions,

has been edited by Horst Appuhn, Chronik des Klosters Wienhausen (Celle: Bomann-

Archio, 1956); the blood miracles are on 140-42. We have records of several fourteenth-

century donations to maintain an eternal light before the holy blood; see Appuhn, "Der

Auferstandene und das Heilige Blut," 98. Contemporary accounts from Rothenburg ob

der Tauber also show some confusion about the source of the blood relic there. And see

n. 25 above on F~camp.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 695

around 1300 seen as vio

such stories involve not

but the quite frequent

tian women and crimin

became a kind of crucif

cases on the iconographic

Christ's torture). What

Golgotha, images that e

that display bloody sp

containers for repeated

any tale of violation, t

proaches and accusation

If those who flocked to

those who propagated t

type of blood from ano

the point of rejecting

relics especially raised

treatise on the eucharis

can be asked whether C

blood which he poured

shall not perish (Luke

perish which was of the

however, rejected entir

remained on earth after the ascension.37

In the course of the thirteenth century, queries about Christ's blood

were raised in discussions of visions, eucharist, resurrection, the

nature of the hypostatic union, and relics. According to Matthew

Paris, Grosseteste defended veneration of the heart's blood from

Christ's right side.38 Aquinas argued, in contrast, that the red and

living blood of the heart shed at death was part of Christ's core human

nature (as opposed to material, such as fingernails, sloughed off in

growth). It thus remained united with his divinity during the triduum

36. Romuald Bauerreiss, Pie Jesu: Das Schmerzensmann-Bild und sein Einfluss auf die mittel-

alterliche Frimmigkeit (Munich: Karl Widmann, 1931); see also n. 17 above and n. 77

below.

37. Innocent III, De sacro altaris mysterio, bk 4, c. 30, PL 217, col. 876D-877B. Almost

hundred years earlier, Guibert of Nogent had raised objections to relics of Christ's milk,

teeth, and foreskin; see Klaus Guth, Guibert von Nogent und die hochmittelalterliche Kritik

an der Reliquienverehrung, Studien und Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Benediktiner-

Ordens und seiner Zweige, Supplement 21 (Augsburg: Winfried, 1970).

38. Matthew Paris, Chronica majora, vol. 4, 643, and vol. 6 (reprint 1964), 138-44; see als

Roberts, "Relic of the Holy Blood," 141. Franciscans generally took this position; see

Chenu, "Sang du Christ." And on the entire controversy, see Vincent, Holy Blood,

82-117.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

696 CHURCH HISTORY

(the period between

him from the dead

assumed in assumi

venerated contemp

was easier for Franc

to think that the bo

corporeitatis and th

whip up the devoti

who later followed

pelled to maintain

held together only

could escape.

The doubts of theologians sometimes reached other blood sources.

As is well known, stories of eucharistic visions proliferated in the

thirteenth century and were used, often by preachers and occasionally

by university theologians, to support the doctrine of the real pres-

ence.41 But Dominicans were in general suspicious of such visions and

went to great lengths to argue that such miracles were owing to a

deep spiritual impact on the beholder, not to a change in the host.42 If

39. For a thorough discussion of the concept of the "truth [or core] of human nature" in

twelfth- and thirteenth-century theology, see Philip Lyndon Reynolds, Food and the Body:

Some Peculiar Questions in High Medieval Theology (Leiden: Brill, 1999).

40. Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologica, pt III, quaestio 54, art. 3, in S. Thomae Aquinatis

opera omnia, ed. Robert Busa, 7 vols. (Stuttgart and Bad Cannstadt: Friedrich Frommann,

1980), vol. 2, 853-54; Quaestiones quodlibetales, Quodl. 5, quaestio 3, art. 1, in ibid., vol. 3,

466.

41. See, for example, the numerous eucharistic miracles in Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dia-

logus miraculorum, ed. J. Strange, 2 vols. (Cologne: Heberle, 1851), esp. distinctio 9, and

Gerald of Wales, Gemma ecclesiastica. And see n. 12 above.

42. See Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologica, pt III, quaestio 76, art. 8, in Opera omnia, ed.

Busa, vol. 2, 896; In Quattuor libros sententiarum, bk 4, distinctio 10, quaestio 1, art. 4b, in

Opera omnia, ed. Busa, vol. 1, 473-74; and Berg, "Der Traktat des Gerhard von Kaln," 436

and 441-44. For a detailed discussion of the theology of the "real presence" in the

twelfth and thirteenth centuries and of the concern to avoid too literalist an interpre-

tation, see Hans Jorissen, Die Entfaltung der Transsubstantiationslehre bis zum Beginn der

Hochscholastik (Muinster: Aschendorf, 1965). On eucharistic theology generally, see also

James F. McCue, "The Doctrine of Transubstantiation from Berengar through the

Council of Trent," Harvard Theological Review 61 (1968): 385-430; Edith Dudley Sylla,

"Autonomous and Handmaiden Science: St. Thomas Aquinas and William of Ockham

on the Physics of the Eucharist," in John E. Murdoch and Edith D. Sylla, eds., The

Cultural Context of Medieval Learning: Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on

Philosophy, Science and Theology in the Middle Ages-September 1973, Boston Studies in the

Philosophy of Science 36 (Boston: D. Reidel, 1974), 349-91; Stock, Implications of Literacy,

241-325; Burr, Eucharistic Presence and Conversion; Macy, Theologies of the Eucharist; Macy,

"The Dogma of Transubstantiation in the Middle Ages," Journal of Ecclesiastical History

45.1 (1994): 11-41, reprinted in Treasures from the Storeroom: Medieval Religion and the

Eucharist (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1999), 81-120; and "Reception of the

Eucharist According to the Theologians: A Case of Diversity in the Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Centuries," in ibid., 36-58.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 697

in transubstantiation on

Christ's body could no

thirteenth- and fourtee

versus annihilation in eu

not just to support real p

Christus) on the altar a

other words, to protect

fragmentation.44

Indeed historians have

theologians to the wond

Ages. For example, when

logian and member of

hosts of Wilsnack in th

visual evidence in the m

theological issues. Tocke

it [the wonderhost] in my

pieces that were already

certainly not red or red-l

And even if it were red

and even if it were blood

Christ... to be venerated

years."45 In 1451, the pa

We have heard from man

how the faithful stream to

worship the precious blood

a transformed red host..

greed for revenue.... [But

43. Thomas Aquinas, Summa the

4, in Opera omnia, ed. Busa, vo

substance and accidents to ar

accidents of bread, whereas th

well; see Andre Goossens, "R

Haquin, ed., Fate-Dieu, 173-91,

the Poetry and Art of the Cath

44. Burr, Eucharistic Presence an

tionslehre; and n. 42 above. Th

Dominicans) for trans-substant

undergirded by their desire to a

and to adhere as well to the Bo

two poles in a relationship of c

Identity (New York: Zone, 200

The Mass of St. Gregory in the

in the Middle Ages, Proceeding

2001, ed. Anne-Marie Bouche a

45. Hartmut Kiihne, " 'Ich ging

from Tocke's Notiz.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

698 CHURCH HISTORY

it without damage t

glorified body of Ch

glorified veins. In or

tion of simple folk,

no longer promulga

In late-fifteenth-ce

eucharist" maintain

flesh or a child or

is a miracle for the

The priest should t

individual claim is

the priest should r

miraculous one sho

nity for a crowd to

Debates over visio

blood in triduum an

Middle Ages. In the

Paul II halted some

veneration of bloo

Nicolas V indeed im

blood came from d

the church permitt

the increasingly fre

less, the phenomen

nounce on their ont

46. Peter Browe, "Die eu

Quartalschrift 37 (1929):

47. Wolfgang Brtickner,

zum historischen Verstin

(1996): 139-66, esp. 151.

48. R. Haubst, "Blut Chris

im Mittelalter," Theologis

vol. 6 (Berlin: de Gruyt

Rudolf, "Die Heilig-Blut-

halt;" and Berg, "Der Tr

49. Chenu, "Sang du Chris

39-40; and Kasper, "De

permitted blood veneratio

forbade further discussi

Passion. In the early sixt

was poured out did part

Verehrung im Uberblick

came to think that anyt

hypostatic union; see K

sixteenth century, Pete

came not from the veritas humanae naturae of Christ but rather from the excess blood of

humors; see Berg, "Der Traktat des Gerhard von Kiln," 454-55.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 699

on the subject, second,

hosts be displayed alon

idolatry,50 and third,

hidden, even their conta

For all the popular ent

struggled to pull a spir

back toward wholeness

toward host, body, Ecc

As increasing demands f

authorities to limit blood cult were understood as an assertion of

clerical control, a move against the people's access.52 To some

logians and prelates, Christ was to be encountered most powerf

his unseen eucharistic presence at mass. The real blood w

Nicholas of Cusa stressed, "completely un-seeable in glorified

Access for laity should be via the host at mass, either taken rever

from the hands of priests or viewed from afar at the mome

elevation. Body and blood were seen only through-that is, beh

beyond-the species on the altar. And blood was doubly veiled

the laity received it only by concomitance, in the round white wa

the body of Christ. Nevertheless, many Christians, suppor

clergy (including bishops, friars, and even popes), cried out for a

physical, a more labile and multivalent, presence. "Blood of C

save me!" They journeyed across Europe to sites such as Wilsn

Weingarten, Orvieto, and Andechs, seeking the holy blood

fluid, scintillating redness carried overtones both of violatio

hence vengeance against enemies) and of breach (hence access

very heart of God). Whatever they saw in the vials and monst

held out to them, they revered it as sanguis Christi offered pro n

Calvary.

III. GERHARD OF COLOGNE

As this brief overview suggests, the relationship of blood venera-

tion to eucharistic devotion in the high Middle Ages was complex an

highly problematic. In order to demonstrate this further, I turn to the

Tractatus de sacratissimo sanguine domini, composed in 1280 by Gerhar

(called Saxo), a Dominican from Cologne. The treatise, which h

50. Boockmann, "Der Streit," 391-92.

51. Briickner, "Liturgie und Legende."

52. See n. 74 below for a Reformation image that makes clear the demand for return of

blood to the laity. As both my brief account here and the large bibliography on Wilsnack

(see n. 32 above) should make clear, differing opinions about blood relics, wonderhosts,

and bleeding images do not fall into an elite versus popular or a clerical versus lay

pattern.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

700 CHURCH HISTORY

recently been publ

of abbot Hermann

relic against skepti

Gerhard's treatise

(His recent editor w

anti-Semitic, polem

example of how co

and eucharistic pie

most certainly Ge

Albert the Great),

eucharistic theolog

and in an apocalypt

practices. It thus u

front in these mat

generalizations abou

tion.

Gerhard's treatise falls into five parts: praise of the precious blood,

a defense against critics, an account of its history from Longinus to the

reception at Weingarten, a call for pilgrimage to the Weingarten relic,

and a short confirmation of the abbey's friendship with Mantua, from

which the blood came. Gerhard begins by arguing that Christ has left

believers both Testaments, the Jews themselves (spared by the church

to serve as an eternal reminder of Christ's suffering), the sacrament of

the altar, and the instruments that took his life (cross, nails, lance, and

thorns). Yet despite all these signs, some Christians remain lazy,

complacent, numb, even in the last days Gerhard fervently believes

are upon them. So Christ, "who knew all beforehand," has left his

blood itself that those sleeping "may come again to love" through "the

sight of blood drops before their eyes."55 We can thus be like Doubt-

ing Thomas, "who came to belief later than the others and had to

touch the scars;" but we are more than Thomas, for he felt only

wounds whereas we "see the blood itself, rose-colored and shining

red." There are, says Gerhard, "pseudo-philosophers," followers of

Aristotle, Pythagoras, and Hippocrates, who argue that Christ could

53. On Gerhard, see Berg, "Der Traktat des Gerhard von K61n," 435-57. There is no

evidence that he is the same person as the Gerhard of Cologne whose sermons have

been edited by Ph. Strauch or the Gerhard who wrote the De medulla animae. Gerhard's

Tractatus de sacratissimo sanguine domini is edited and translated into German (somewhat

freely) by Berg, in "Der Traktat des Gerhard von Kaln," 459-76. On Weingarten, see 900

Jahre Heilig-Blut-Verehrung, ed. Kruse and Rudolf, 3 vols.

54. Berg, "Der Traktat des Gerhard von K61n," 453-55; on Gerhard see also Nagel, "Das

Heilige Blut," 193-94.

55. Gerhard argues that the name "Weingarten" was prophetic; Christ knew there would be

a blood relic there. See Tractatus de sacratissimo sanguine, 474.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 701

not have risen whole (

and living blood (the bl

naturae). Yet we know

the Mount of Olives, an

saw there true blood. H

blood on earth to inflam

make his subtle and gl

ciples, so he could not

and yet left it behind

Cannot one and the sa

moment be changed in

priests, really here prese

[in heaven]?"56

Complex theological ar

of Christ in resurrection and in eucharist are here used to bolster the

claims of relic against eucharist. If by concomitance, all Christ is i

every particle, then (argues Gerhard) Christ's blood can be totally

heaven and yet present both in the eucharist and in relic. If Christ

body after the resurrection was so glorified and subtle that it could go

through doors and yet was touch-able by Thomas the Doubter, so h

blood can be glorified (almost immaterial) in heaven and yet palpab

drops (see-able, touch-able and even drink-able) here on earth.

Gerhard's account, the visual piety (Schaufrbmmigkeit) so emphasiz

recently by scholars as a characteristic of eucharistic devotion

turned against eucharist: yes, the sacrament can be received by th

eyes, but it is under a veil, whereas the throbbing, shimmering, living

blood is see-able without a covering.57 Subtle arguments about sub

tilitas and wholeness are all very well for pseudo-philosophers, sa

Gerhard, but Christ is himself a doctor who appeals directly to ord

nary hearts. Gerhard thus aligns himself not only with the monks

Weingarten who commissioned his treatise but also with popul

piety and against his fellow Dominicans.

Around these anti-intellectual uses of quite learned arguments (n

always very fairly deployed) floods a plethora of images for the ho

56. Gerhard, Tractatus de sacratissimo sanguine, 467. Thomas of Chobham in his treatise

preaching (ca. 1210) makes similar use of the eucharistic analogy. Discussing ho

Christ's foreskin can both remain on earth and be resurrected, Thomas asserts: "just

by a miracle the body of Our Lord can be at one and the same time in several places,

that body can exist in several forms. ... Christ's foreskin, glorified as part of his integ

body, may exist in another place unglorified." Cited in Vincent, Holy Blood, 85.

57. See Jensch, "Die Weingartener Heilig-Blut- und Stiftertradition," 23, and Nagel, "D

Heilige Blut," 200-201. The late-thirteenth-century indulgences at Weingarten were f

seeing the relic; and the crystal form of the reliquary clearly corresponded to th

devotional emphasis.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

702 CHURCH HISTORY

blood. It is dew, se

quencher of thirst,

tilla), from which a

is suffering, tortu

yet an indictment

it is accusation as well as violation. It accuses the Jews who (in

Gerhard's view) killed Christ, but it also charges the Christians of

Gerhard's own day with being the "new Jews," who kill Christ again

by their lethargy and neglect. In contrast to many other theologians,

Gerhard's word of choice for the relic he defends is cruor (bloodshed)

not sanguis.

At the end of the treatise, in a passage reminiscent of Aelred's

depiction of the crucifixion, Gerhard suddenly shifts to blood as wine.

The imagery undoubtedly reflects the ritual known as "blood-

drinking" (that is, imbibing of wine that had been poured over the

reliquary or into which the relic had been dipped-a ritual we know

was practiced at Weingarten).58 Gerhard writes:

You, the true vineyard [that is, Weingarten], surpassing all others,

[are] where the health-bringing wine out of the side of the Lord

makes believers intoxicated with the wonderful drunkenness of

which the Psalmist speaks.... You, fertile and fecund vineyard, [a

planted by God. ... So that you are made fertile, God has let his mil

rain flow out of the highest clouds, his flesh, which never bore sin

But so that you may become drunk with the juice of the grape,

same Christ has poured out his totally pure blood from the winecel

lar of his flesh; and the Lord wanted this intoxicating wine, th

fructifying rain, this soul-cleansing water to be drunk and stored u

in his most glorious vineyard [Weingarten].59

But blood as wine comes in Gerhard's treatise almost as an after-

thought, following blood as dew and water, fructifying and clean

blood as fire, inflaming and inebriating; blood as reproach, ac

Jews and Christians of violating Christ. There is eucharistic im

here, it is true. But this eucharistic imagery (like the eucha

58. See above n. 20, and Hans Ulrich Rudolf, "Heilig-Blut-Brauchtum im Uberblick

Jahre Heilig-Blut-Verehrung, vol. 2, 553-74. The earliest miracles at Weingarten

have come from being touched by the Holy Blood reliquary or from visitin

Meingoz's grave or both; see Norbert Kruse, "Der Bericht von den ersten Wund

Heiligen Bluts im Jahre 1200," in 900 Jahre Heilig-Blut-Verehrung in Weingarten,

124-36.

59. Gerhard, Tractatus de sacratissimo sanguine, 474-75.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 703

practice of blood-drink

the relic by which it is

To Gerhard, therefor

Christ's side to provide

"The blood is changed i

a hundred and thirty

bringing wine out of t

cated.... Christ has po

winecellar of his flesh.

of the grape." To Aelre

logically, figuratively,

blood as inflamer of m

Christ, but, initially and

There are many facto

horror of what some h

piety. I am not able to

the history of blood r

may have read languag

too narrowly or exclusi

true that liturgy and t

host central to practic

out-leaping from hos

goating, those who did

pressure to keep bloo

symbol of community

such as Gerhard-who

charist. The way in wh

body was magnified by

that is, by the fact th

spirituality centered on

based in physical contin

words of consecration a

historical filiation, the

has elegantly put it, "rea

was available in two

60. Dinzelbacher, "Das Blut Ch

religious at Wilsnack that the

crated wine.

61. Peter Dinzelbacher, "Die 'Realprisenz' der Heiligen," in Heiligenverehrung in Geschichte

und Gegenwart, ed. P. Dinzelbauer and D. Bauer (Ostfildern: Schwabenverlag, 1990)

115-74. One must not, however, take the point too far; relics were also, even to simple

adherents, triggers of remembrance-that is, mnemonic as well as thaumaturgic.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

704 CHURCH HISTORY

through the matte

and torment-bloo

IV. THE ASYMMETRY OF SYMBOLS

The asymmetry of body and blood is, however, rooted in something

deeper than the historical traditions of blood relic and eucharist, and

this is the second point I wish to underline in my essay. From the

eleventh century, blood took on, so to speak, a life of its own. Blood

visions and blood devotions proliferated, flowing free of any anchor-

ing to eucharist or relic. In 1010 Ademar of Chabannes saw a great

crucifix "high against the southern sky.., .as if planted in the heav-

ens" and on it hung the crucified one "the color of fire and deep

blood."62 In ca. 1060, the reformer Peter Damian, contemplating alone

in his cell, saw Christ "pierced with nails, hanging on the cross" and

wrote, in what may be the first example of such visionary drinking

"with my mouth I eagerly tried to catch the dripping blood."'63 In the

late twelfth century, an English monk from Evesham abbey was found

as if lifeless on Good Friday with "the balls of his eyes and his nose

wet with blood." Once recovered, the monk recounted to his brothers

a vision of the cross.

While I was kneeling before the image and was kissing it on the

mouth and eyes, I felt some drops falling gently on my forehead.

When I removed my fingers, I discovered from their color that it was

blood. I also saw blood flowing from the side of the image on the

cross, as it does from the veins of a living man when he is cut for

blood-letting. I do not know how many drops I caught in my hand

as they fell. With the blood I devoutly anointed my eyes, ears and

nostrils. Afterward-if I sinned in this I do not know-in my zeal I

swallowed one drop of it, but the rest, which I caught in my hand, I

was determined to keep.

Following this encounter, the monk traveled in vision through th

places of punishment, graphically described, and thence to the place

of glory. But even in the midst of glory, there was blood. "The tongue

cannot reveal nor human weakness worthily describe what we saw a

we went on.... In the middle of endless thousands of blessed spirit

62. Ademar of Chabannes, Historia 3.46, trans. in Richard Landes, Relics, Apocalypse and t

Deceits of History (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995), 87. See below n

65.

63. Peter Damian, Opusculum 19: De abdicatione episcopatus [Letter 72], c. 5, PL 145, col. 432B,

trans. Owen J. Blum, The Letters of Peter Damian, 1-120, The Fathers of the Church,

Mediaeval Continuation, 4 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America

Press, 1989-98), vol. 3, 129-30; Dinzelbacher, "Das Blut Christi," 425, n. 147, says this is

the first such vision.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 705

who stood round,... the

It was as if he were han

from scourgings, insulte

driven into him, pierced

over his hands and feet

side!"64

Scholars have usually b

blood mysticism and t

eleventh century, of so

question of the origin

affective mysticism or b

particular asymmetry w

find a clue in the natu

gists tell us, "natural

connotations brought f

symbols are multivalen

physiological sense con

boundaries, intricately

through eating and th

munity and of self. Bl

more complex and labi

and death. It is sanguis

European languages a

64. "The Monk of Evesham's V

Heaven and Hell Before Dante

65. Both Rachel Fulton and Phy

origins of the devotion to the

Passion: An Intellectual Histor

Columbia University Press,

Chabannes and Peter Damian

66. See, for example, Mary Dou

intro. (New York: Pantheon,

Hurley (New York: Vintage,

society as "a society of blood,

stresses the symbolic importa

on. I pointed out the symbolic

chapter of Holy Feast and Hol

There are some interesting ide

(Paris: Fayard, 1988) but it is

moyen dge, ed. Faure, are usef

attempts no overview of bloo

67. Hence Miri Rubin's argume

Christi, 3-5, 11, 288, etc.) see

polyvalent and culturally c

particular perspective. But th

everything. The symbol itself

empirical question into which

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

706 CHURCH HISTORY

sense, life) and out

between bloods is e

To speak in this wa

language causes se

agents who bring th

is to argue that sym

they totally constru

Going back throug

the Hebrew Script

was thus equated

writing, the body/

the opposition bod

fertile, curative,7

eval clergy came t

the chalice. Small wonder too that reformers from the fourteenth to

the sixteenth centuries, whatever their technical theologies of euch

ristic presence, saw the administering of the cup to the laity as a

68. Georges Dumezil, "Le sang dans les langues classiques," Nouvelle revue franqai

d'hdmatologie 25 (1983): 401-4. (Interestingly enough, German does not have th

distinction.)

69. As it is in many religions; see A. Closs, "Blut," LTK, vol. 2, cols. 537-38; Schumann,

"Blut: religionsgeschichtlich," in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart: Handwarter-

buch ftir Theologie und Religionswissenschaft, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Tiibingen: Mohr [Siebeck],

1927), cols. 1154-56; and Kasper, "Der bleibende Gehalt," 377-80. Grosseteste (according

to Matthew Paris) states this explicitly; see Matthew Paris, Chronica majora, vol. 6, 143.

70. For example, Alger of Liege, De sacramentis corporis et sanguinis Dominici, bk 2, c. 8, PL

180, col. 826D. For other examples, among them Peter Lombard, Rupert of Deutz,

Gerald of Wales, and Peter the Chanter, see Macy, Theologies of the Eucharist, 64-70, and

Dinzelbacher, "Das Blut Christi," nn. 58 and 67. Medieval authors themselves explored

the connection of the physical object and its religious significance. Robert of Melun (d.

1167), for example, argued that God can change anything into anything but in fact he

converts bread to flesh and wine to blood because wine has more "similitude" with

blood; see Jorissen, Die Entfaltung der Transsubstantiationslehre, 27-28.

71. In the later Middle Ages, the blood was sometime carried in procession aroun

sown fields to protect crops and increase fertility; see Rudolf, "Die Heili

Verehrung im Uberblick," 16. And on women's blood as food to fetus and suckl

Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the

Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone, 1991), 181-238.

72. Hans Wissmann, Otto Bbcher, and Walter Michel, "Blut...," TRE, vol. 6, 727-38; and

Mitchell B. Merback, The Thief, the Cross, and the Wheel: Pain and the Spectacle of Punish-

ment in Medieval and Renaissance Europe (London: Reaktion, 1999), 97-98. Note the

prominence of blood as healing in the story of Longinus. See also R. Po-chia Hsia, The

Myth of Ritual Murder: Jews and Magic in Reformation Germany (New Haven, Conn.: Yale

University Press, 1988), 9, 143-51.

73. For the power of cannibalistic images, see Holy Feast and Holy Fast, 319, n. 75, 412, n. 77;

and Schumann, "Blut: religionsgeschichtlich," cols. 1154-56. For the motif of blood-

eating in popular piety, see Frederic C. Tubach, Index exemplorum: A Handbook of

Medieval Religious Tales, FF Communications 204 (Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Sciences

and Letters, 1969), number 761.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 707

audacious act of rebelli

diate access to God.74

But blood was also cruor: death, discord, suffering, horror, division.

It was escape from body and destruction of body; it breached body. It

was the drops, bits, fragments, of which Aelred and Gerhard so

insistently speak. Throughout medieval miracle collections stream

stories of bits of hair, walls, utensils-as well as, of course, the host

itself-that bleed in order to display insults and accuse perpetrators.75

Christian sin itself was represented as bodily transgression, blood-

shedding-for example, in the late medieval devotional image known

as the Feiertagschristus, which depicts peasants and peasant imple-

ments bloodying Christ by disobeying the Third Commandment.76

However horrifying it is, it is (alas!) not surprising that blood relics-

and hosts (bodies) breached by blood-were associated not only with

relatively innocent competition among religious houses, cities, and

monachies but also with pogroms and crusades, the slaughtering of

Jews, and the persecution of heretics.77

74. See the woodcut from 1530 in Leopold Kretzenbacher, Bild-Gedanken der spiitmittelalter-

lichen HI. Blut-Mystik und ihr Fortleben in mittel- und siidosteuropiiischen Volksilberlieferun-

gen (Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1997), 89, figure 10.

Here Martin Luther and Jan Hus give the Lord's Supper under both species in front of

an altar with a huge grape vine curling around a chalice or basin that contains the

crucified Christ als Blutquell.

75. For objects that accuse by bleeding, see n. 17 above, and see also Peter Browe, "Die

Eucharistie als Zaubermittel im Mittelalter," Archiv fiir Kulturgeschichte 20 (1930): 134-

54. On the theme of horror cruoris, see n. 8 above.

76. Robert Wildhaber, "Feiertagschristus," in RDK, vol. 7, cols. 1002-1010. See also Rudolf

Berliner, "Arma Christi," Miinchner Jahrbuch der Bildenden Kunst 3rd ser., vol. 6 (1955):

68, who sees the motif more broadly as "Christ attacked by the sins of the world," and

Douglas Gray, Themes and Images in the Medieval English Religious Lyric (London:

Routledge and K. Paul, 1972), 51-54, who gives examples of the theme in devotional

literature.

77. See Bauerreiss, Pie Jesu; Browe, "Die Eucharistie als Zaubermittel;" Lionel Rothkrug,

"Popular Religion and Holy Shrines: Their Influence on the Origins of the German

Reformation and Their Role in German Cultural Development," in Religion and the

People, 800-1700, ed. J. Obelkevich (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1979), 20-86, esp. 27-8; F. Lotter, "Hostienfrevelvorwurf und Blutwunderfiilschung bei

den Judenverfolgungen von 1298 ('Rintfleisch') und 1336-1338 ('Armleder')," in

Fiilschungen im Mittelalter: Internationaler Kongress der Monumenta Germaniae Historica,

Miinchen, 16.-19. September 1986, 5 vols. (Hannover: Hahn, 1988), vol. 5, 533-84; Hsia,

The Myth of Ritual Murder; Rainer Erb, ed., Die Legende vom Ritualmord: Zur Geschichte der

Blutbeschuldigung gegen Juden (Berlin: Metropol, 1993), especially Friedrich Lotter, "In-

nocens Virgo et Martyr: Thomas von Monmouth und die Verbreitung der Ritual-

mordlegende im Hochmittelalter," 25-72; Diane Wood, ed., Christianity and Judaism:

Papers Read at the 1991 Summer Meeting and the 1992 Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical

History Society, Studies in Church History 29 (Oxford: Published for the Ecclesiastical

History Society by Blackwell, 1992); J. M. Minty, "Judengasse to Christian Quarter: The

Phenomenon of the Converted Synagogue in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Holy

Roman Empire," in Popular Religion in Germany and Central Europe, 1400-1800, eds. R.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

708 CHURCH HISTORY

V. AN EXAMPLE FROM ICONOGRAPHY

It is this blood--complex symbolically and historically-that pou

out in late medieval art and devotion, threatening body by breachi

but also, by this same breaching, offering access. I turn for a fin

illustration to the familiar but exceedingly complex iconography o

the so-called Mass of St. Gregory, the earliest examples of which

appear about 1400.78 [See Figures 1 and 2.] Often said to go back to

story in Paul the Deacon's Life of Gregory, in which a woman

convinced of the real presence by the apparition of a bloody finger in

place of bread, the motif may, in fact, have nothing to do with ear

accounts of Gregory except insofar as they emphasize his devotion

the eucharist and his efficacy at gaining release for souls in the period

of purgation after death.79 Whatever its origins (and they may w

Scribner and T. Johnson (New York: St. Martin's, 1996), 58-86; John McCulloh, "Jewis

Ritual Murder: William of Norwich, Thomas of Monmouth, and the Early Dissemina-

tion of the Myth," Speculum 72.3 (1997): 698-740; Robert C. Stacey, "From Ritua

Crucifixion to Host Desecration: Jews and the Body of Christ," Jewish History 12.1 (1998

11-28; and Miri Rubin, Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews (Ne

Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999). Blood can, of course, have denotations an

connotations of community, especially in a family or racial sense, as the rhetoric

National Socialism makes clear; see Kasper, "Der bleibende Gehalt," 378. I have di

cussed these issues in "Violent Imagery in Late Medieval Piety," Bulletin of the Germa

Historical Institute 30 (Spring, 2002): 3-36.

78. The earliest example (ca. 1400) seems to come from St. Georg, in Riziins (Graubiinden

Switzerland, although some consider this a precursor or a parallel tradition; see Berlin

"Arma Christi," plate 18 on 68. According to Marianne Lorenz, "Die Gregoriusmes

Entstehung und Ikonographie" (Diss., Masch.-Schr., Innsbruck, 1956), the earliest exam

is a relief in the parish church of Miinnerstadt (1428). On the Gregorymass generally

Herbert Thurston, "The Mass of St. Gregory," The Month 112 (1908): 303-319; J. A. Endre

"Die Darstellung der Gregoriusmesse im Mittelalter," Zeitschriftfiir christliche Kunst 30.11-

(1917): 146-56; Louis R6au, Iconographie de l'art chritien, vol. 3, pt 2 (Paris: Presses univer

sitaires de France, 1958), 609-15; Comte J. de Borchgrave d'Altena, "La Messe de saint

Gregoire: Etude iconographique," Musees royaux des beaux-arts: Bulletin; Bulletin Koninklij

Musea voor Schone Kunsten 8 (1959): 3-34; Carlo Bertelli, "The Image of Pity in Santa Croce

Gerusalemme," in Douglas Fraser, Howard Hibbard, and Milton J. Lewine, eds., Essays

the History of Art Presented to Rudolf Wittkower (London: Phaidon, 1967), 40-55; Colin Eisler

"The Golden Christ of Cortona and the Man of Sorrows in Italy," The Art Bulletin 51.2 (Jun

1969): 107-118, 233-246; Westfehling, Die Messe Gregors des Grossen, especially 16-54; Bri

itte d'Hainaut-Zveny, "Les messes de saint Gr6goire dans les retables des Pays-Bas. Mise en

perspective historique d'une image poldmique, dogmatique et utilitariste," Bulletin: Musees

royaux des beaux-arts de Belgique, Bruxelles 41-42 (1992-93): 35-61; and Flora Lewis, "Rewar

ing Devotion: Indulgences and the Promotion of Images," in Diana Wood, ed., The Chur

and the Arts, Ecclesiastical History Society (Oxford: Published for the Ecclesiastical Histor

Society by Blackwell, 1992), 179-94. Thomas Lentes and the Art History Research Group a

Miinster are preparing an extensive catalogue of Gregorymass iconography. I discuss t

iconography in Bynum, "Seeing and Seeing Beyond."

79. To say that the image does not originate as an illustration of Paul the Deacon does no

of course mean that there is no connection of Gregory to eucharistic devotion in earl

literature. There is much in Gregory's own writing about the mass, and the devotion

the arma Christi and the Schmerzensmann was early associated with Gregory's feast da

See Westfehling, Die Messe Gregors des Grossen, 16-22.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 709

FIG. 1. Mass of St. Gregory,

wing from the altar of the C

Museum, Luibeck.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

710 CHURCH HISTORY

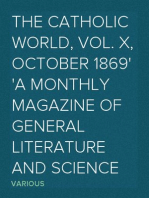

FIG. 2. Mass of St. Greg

Maria zur Wiese, Soest.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 711

have been, as Endres

may have come from

tached),80 the depiction

elements. The first and

the Schmerzensmann (th

his torture (the so-called

is little emphasized (an

indicating that the mo

second (closer to the sto

shows Christ present a

appearing at the elevat

connection to the salvat

an inscription that off

the image84 or through

mass.85

80. See the classic article by

Bertelli, "The Image of Pity in

Gregors des Grossen, 18-22.

81. See, for example, the Grego

from about 1490, in the Ger

duced in Gertrud Schiller, Iko

1966-80), vol. 2, plate 807. For

N. Nemilov, "Gedanken zur g

Beispiel der sog. Gregorsmess

Wege-Beispiel, ed. Brigitte To

blot, 1991), 126, and Westfehl

82. For an example see the altar

ches Museum, Utrecht; reprod

ing to Westfehling, Christ ble

many examples do not show t

inspection reveals, however, t

sometimes bypasses even the

times the chalice is covered by

mass (see, for example, ibid., 40

of Europe and New Spain, 115

83. For an example, see the m

Bibliotheque nationale, Cod. L

Gregors des Grossen, 24, poin

84. See, for example, the altar

of the fifteenth century (the i

Hermitage; see Nemilov, "Ge

123-33 and esp. plate 20. See a

1446; Westfehling, Die Messe

probably our earliest exampl

"Rewarding Devotion."

85. Mass of St. Gregory, attri

Libeck; see Brigitte Heise an

Erliuterung der Bildprogramm

Hansestadt Liibeck, 1993), 67

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

712 CHURCH HISTORY

Once again then in

making througho

both closely connect

own as stimulator

theology, pious pre

within, the rim of t

altarpiece attribute

host almost covers the Schmerzensmann. The wounds are hidden be-

hind a circle whose rim seems to hold in the blood, as George Cart

almost contemporaneous vision suggested.86 The doctrine of conco

itance is made visual; every fragment is whole; body contains blo

In such depiction, blood is included only as part of the body fro

which it flows; it is, like body, a means of incorporation into t

community, Ecclesia, which forms that body.

But even in the Mass of St. Gregory, blood escaped. It flowed in th

Mass, and outside it as well. And it leapt away from the host as w

as leading to it.87 For example, this wing from the St. Anne altar of

Wiesenkirche in Soest, 1473, combines the elements of the Grego

mass I have carefully sorted out-vision, eucharistic celebration, a

purgatory-and yet does more. [figure 2] What we see here before

astonished Gregory is the blood leaping not only from chalice to p

but also from chalice to graveyard where the poor souls who rece

it appear to rise from the dead under its saving power. The impac

this Gregorymass is completely different from that of the alm

contemporary painting attributed to Dedeke. It is not clear whet

mass is being said. The pope wears his tiara;88 the paten is empt

there is no host on the altar linen. Blood takes on a life and direction

an energy, of its own. Although iconographically the Gregorym

was by definition connected to altar and celebrant (it is Gregory w

86. See n. 18 above.

87. Mass of St. Gregory, Wing of the St. Anne Altar, Wiesenkirche, Soest, about

reproduced in Schiller, Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst, vol. 2, plate 806. For

examples, see Hans Georg Gmelin, Spiitgotische Tafelmalerei in Niedersachsen und Br

(Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1974), 162, plate 22.8; 260, plate 67.1; 379, plate 1

381, plate 121.1; 430, plate 142.3; 467, plate 153.1; and 469, plate 154.2.

88. It seems that, from at least the twelfth century on, the pope would have remove

tiara (as bishops today remove the mitre) during the canon of the mass. See J

Braun, Die liturgische Gewandung im Occident und Orient nach Ursprung und Entwick

Verwendung und Symbolik (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1964)

87, and on the tiara as a form of mitre, see Gerhard B. Ladner, "Der Ursprung un

mittelalterliche Entwicklung der paipstlichen Tiara," in Herbert A. Cahn and

Simon, eds., Roland Hampe zum 70. Geburtstag am 2. Dezember 1978 dargebracht

Mitarbeitern, Schiilern und Freunden, 2 vols. (Mainz: Von Zabern, 1980), vol. 1, 44

and vol. 2, plates 86-93. This suggests that the Soest depiction is not of the mome

consecration.

This content downloaded from

129.219.247.33 on Fri, 19 Feb 2021 17:25:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST 713

makes it a Gregorymas

from Christ to penitent

Dedeke version lifts so

crated by the celebran

elevated host echoes th

ders and buttocks) that

is subsumed in the ho

image from Soest, the

carries our eyes not to p

the sharp lines of blood

from chalice and towar

Our eyes go toward C

need salvation. The mo

splinters to our right. B

VI. CONCLUSION

A full exploration of blood piety would necessitate a discussio

almost every aspect of medieval devotion and medieval life

intention here has not been to give a complete history of blood

and blood mysticism but rather to point to the remarkable asymm

of body and blood historians have been inclined to label simpl

cursorily "eucharistic." Hence I have argued that body and

were different kinds of symbols and that blood was doubly

twofold historically as eucharist and relic, twofold symbolical

sanguis and cruor, life and death.

More could be said. But even the material I have explored

suggests three modifications of received wisdom. First, any gen

ization that sees in medieval blood imagery echoes of eucha

devotion must take into account the complex ways in which b

cult departed from and competed with eucharist. As the monk

Weingarten who commissioned Gerhard's treatise or the pilgrim

F camp argued, relic and vision might offer more immediate

than did the (withheld) communion cup. Not every referen

blood, to drinking and eating, to the wound in Christ's sid