Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Planning Fallacy in Oil and Gas Decision-Making

Uploaded by

TheGimhan123Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Planning Fallacy in Oil and Gas Decision-Making

Uploaded by

TheGimhan123Copyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/290821305

The planning fallacy in oil and gas decision-making

Article in The APPEA Journal · January 2010

DOI: 10.1071/AJ09023

CITATIONS READS

2 150

4 authors, including:

Matthew Brian Welsh S. H. Begg

University of Adelaide University of Adelaide

61 PUBLICATIONS 491 CITATIONS 93 PUBLICATIONS 792 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Matthew Brian Welsh on 18 January 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Lead author THE PLANNING FALLACY IN OIL AND

Matthew

Welsh GAS DECISION MAKING

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. INTRODUCTION

Begg

Australian School of Petroleum The planning fallacy

University of Adelaide Decision making under uncertainty, whether regard-

North Terrace ing subsurface geology or future economic conditions, is

Adelaide SA 5005 an integral part of the oil and gas industry. In fact, the

matthew.welsh@adelaide.edu.au industry is often regarded as the classic example of deci-

nigel.rees@student.adelaide.edu.au sion making under uncertainty (Newendorp and Schuyler,

2000). It has been well documented, however, that the oil

hugh.ringwood@student.adelaide.edu.au and gas industry has a poor record when it comes to ac-

steve.begg@adelaide.edu.au curately assessing these uncertainties—costing the sector

upwards of $30 billion per year from unexpected outcomes

ABSTRACT (Goode, 2002).

A specific bias known to affect oil and gas decisions,

The ‘planning fallacy’ describes the tendency of people first described in the 1970s (see Kahneman and Tversky,

to underestimate costs and times required for the comple- 1979), is the planning fallacy. This is the tendency to hold

tion of complex projects. Psychological research has dem- a confident belief that one’s own project will proceed as

onstrated that a key component of this results from the planned, even while knowing that the vast majority of

packing/unpacking bias—where options or problems that similar projects have run late (Kahneman and Tversky,

are not specifically stated tend to be ignored by people 1979). More generally, people are inclined to underestimate

when making estimates or assigning probabilities to events. how long it will take them to complete tasks and projects,

We have investigated this effect as it relates to oil and and how much these projects will cost.

gas decision making, highlighted by experimental results There are countless examples of this phenomenon: the

comparing estimates of drilling times made by both student Panama Canal, Montreal Olympic Stadium, the Sydney

and industry participants. Specifically, participants were Opera House and the Channel Tunnel between Britain and

provided with a drilling scenario and asked to estimate France all suffered heavily from the planning fallacy. A

the time required to drill the well—including drilling, more recent example is the Wembley Stadium-Multiplex

tripping, rigging and all potential problems. In the packed debacle.The stadium was initially scheduled for completion

condition the options were given as just stated while, in the in 2003; however, destruction of the old stadium was not

unpacked condition the ‘all potential problems’ category even completed by this time. Subsequent financial, legal

was divided into a list of specific problems. and construction knock-on delays resulted in a reschedule

The packing effect was shown to markedly alter the of the expected completion time to May 2006, to be ready

time estimates made by all groups of participants—alter- for the FA Cup final; however, construction was further

ing estimates of problem times by more than 100 hours delayed and only completed in March 2007, some four

on average. Additional analyses assessed the interactions years later and estimated to be $109 million over budget

between the packing/unpacking effect and personal traits (Long, 2005). A study of oil and gas projects has showed

such as optimism, tendency to procrastinate and industry that the industry is equally susceptible to this bias, with an

experience. These findings are discussed in terms of their analysis by Merrow (2003) concluding that mega-projects

import for oil and gas decision makers desiring to improve (those requiring investments of over $1 billion) suffered

prediction accuracy and, thus, economic outcomes by an average of 46% cost and 28% time overruns.

avoiding, or limiting, the impact of the planning fallacy.

What causes the planning fallacy?

KEYWORDS

People plan tasks on a daily basis and have, over the

Decision making, planning fallacy, optimism, procras- course of their lives, had ample opportunity to learn that

tination, bias. their completion predictions suffer from an optimistic bias

SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10 APPEA Journal 2010 50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE—1

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. Begg

(Koole and Spijker, 2000). With this in mind, we must ask desired conclusion. Koole and Spijker (2000) argue that

why people continue to fall victim to the planning fallacy. the notion of motivated reasoning also extends to the task

Buehler et al (1994) summarised three main elements of generating completion predictions. People’s wishes and

in people’s predictions of task completion times: people desires thus affect their tendency to engage in scenario

underestimate their own but not others’ completion times; thinking, thereby producing a change in their level of op-

people focus on plan-based scenarios rather than on rel- timistic bias.

evant past experiences while generating their predictions;

and people’s attributions diminish the relevance of past UNPACKING

experiences.

Kruger and Evans (2004), however, suggest that taking

INSIDE/OUTSIDE PERSPECTIVE an inside perspective does not always result in a planning

fallacy. They argue that the planning fallacy is, often, a

The first of Buehler et al’s (1994) points refers to the result of just the opposite—not analysing the task enough

proposal from Kahneman and Tversky (1979) that opti- in an inside perspective. They hypothesise that prompting

mistic predictions are made when one considers an inside people to think more about the task at hand and its indi-

or singular view to estimating a task completion time. vidual components can lead to a decreased—as opposed

This involves looking at the task’s specific aspects and to an increased—planning fallacy.

how they will be completed. This is opposed to an outside This approach follows from the work of Fischoff et al

or distributional view, which is when one considers the (1978), who showed that people’s assessments of the likeli-

task in a broader perspective including knowledge of how hood of various events was affected by the manner in which

long similar tasks have taken to complete and possible the events were presented. Specifically, they showed that

complications delaying progress. Ideally, of course, people people’s assessments of the probable reasons for a car not

should conduct their predictions using both singular and starting were limited by the explicit options available to

distributional information. The existence of the planning them. That is, the weight assigned to a catch-all ‘all other

fallacy, however, implies that people implement an internal problems’ category was found to be much less than the

perspective when predicting completion times. Specifically, weight assigned to the explicit categories that comprised

it seems that people tend to overlook their past experiences that general category.

and judge each new project as a singular event. That said, While not referring to this effect specifically, Tversky

people readily adopt an outside approach when making and Koehler’s (1994, pp. 332–3) statement regarding sup-

predictions for other people’s projects’ completion times— port theory is germane:

recognising that a project of particular type is likely to take ‘When people assess their degree of belief in an

approximately as long to complete as similar projects.This implicit disjunction, they do not normally unpack the

is known as the actor-observer differences in prediction; hypothesis into its exclusive components and add their

we are not surprised if our neighbour’s house extension support, as required by extensionality. Instead, they tend

runs overtime, or if a colleague misses a deadline, as we to form a global impression that is based primarily on

have repeatedly seen these types of event, yet we do not the most representative or available cases. Because this

always make the leap to considering our own projects in mode of judgment is selective rather than exhaustive,

this distributional manner (Buehler et al, 1994). unpacking tends to increase support. In other words,

More generally, the consensus from researchers is that the support of a summary representation of an implicit

people typically arrive at their predictions by constructing hypothesis is generally less than the sum of the support

a mental scenario that sketches out how a given project of its exclusive components.’

is likely to develop (Buehler et al, 1994). As humans are Applying this thinking to the planning fallacy suggests

incapable of predicting all possible outcomes of an event, that one reason why people may set optimistic task

these mental scenarios neglect many alternative ways in completion times is that they do not naturally unpack

which the future might unfold. This process of scenario those tasks into their various subcomponents (Kruger and

thinking influences people to hold on to their favourite Evans, 2004).

versions of the future, causing people to repeat their past

mistakes despite their knowledge of past outcomes (Bue- PERSONAL TRAITS

hler et al, 1997).

This is a form of motivated reasoning (Buehler et al, A secondary concern for those interested in the plan-

1997), a phenomenon in which people’s reasoning is af- ning fallacy is whether there are individual traits that

fected by motivational factors. Kunda (1990) proposed result in greater or lesser susceptibility to the bias. For

that motivation may affect reasoning through reliance on example, one might expect that more experienced people,

a biased set of cognitive processes—that is, strategies for having seen a greater variety of tasks of the type under

accessing, constructing, and evaluating beliefs. The mo- consideration, might be less susceptible. This is, however,

tivation to be accurate enhances use of those beliefs and at odds with both the inside/outside view explanation

strategies that are considered most appropriate, whereas presented above (which argues that people tend to ignore

the motivation to arrive at particular conclusions enhances past results) and the results from Fischoff et al’s (1978)

use of those that are considered most likely to yield the study where mechanics were shown to be just as likely

2—50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE APPEA Journal 2010 SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10

The planning fallacy in oil and gas decision making

to fall victim to the packing of specific categories for a tive displayed a marginally significant tendency to over-

car not starting into a general one as a student sample. estimate their completion times; that is, they tended to

Other traits one might expect to impact on the planning predict more pessimistically. These findings indicate that

fallacy include optimism and the tendency to procrasti- motivational reasoning has the ability to influence the

nate. The research on these questions has, however, been degree of optimistic bias by affecting people’s tendency to

varied, and it seems unclear as to whether certain effects engage in scenario thinking (Koole and Spijker, 2000) and,

described result from stable, personality traits or contex- thus, Buehler et al (1997) argue that it may be possible to

tual drivers. For example, Buehler et al (1997) identified eliminate the planning fallacy altogether by substituting

that incentives to finish a task promptly tended to increase speed incentives for accuracy incentives.

the optimistic bias in time prediction and increased the An alternate approach is the one put forward by Kruger

tendency to neglect or underweight previous experiences. and Evans (2004)—if the planning fallacy results from

While optimistic time predictions provide initial impetus a failure to unpack a task into its constituent subtasks,

to get a project underway, any benefit of this diminishes then unpacking a task prior to having participants make

over time and consequently long-term projects can suffer estimates should increase the accuracy of their estimates.

considerably (Buehler et al, 1997). In this context, then, it This approach is the one that we test herein as it requires

seems less than clear whether the optimism referred to no incentives and has been shown to increase accuracy in

is, in fact, an attribute of the individual. simple oil-industry related questions (Welsh et al, 2005).

Similarly, Pezzo et al (2006) suggested that self-pre-

sentation motives can lead to an increase in optimistic Aims and hypotheses

planning. A key attribute in time prediction for projects

is that they are normally required to be reported to other The present studies chiefly look at whether the plan-

people (such as management). As a direct consequence, ning fallacy is observed in an oil and gas decision-making

people tend to make optimistically biased time predictions task, and what impact a variety of variables have on its

in order to present well to others. Thus, accountability has strength. Specifically, we are interested in whether: un-

little effect on debiasing the planning fallacy as making packing a task into more comprehensive sub-tasks lessens

time predictions available to the public also increased its effects; participants of differing levels of experience

self-presentation concerns. In neither case, however, was are affected differently; having received training in deci-

the individual’s baseline level of optimism considered a sion making grants a benefit; and, people with different

potential contributor to the planning fallacy. personality traits differ in their estimates or susceptibility

Procrastination, by contrast, has been specifically dis- to the planning fallacy.

cussed in terms of the planning fallacy but the results are

not clear. Given that procrastination, by definition, involves HYPOTHESES

the behaviour of postponing task initiation (Ferrari et al,

1995) one would expect that this would have an impact H1. People in the unpacked condition will estimate longer

on completion times. Specifically in terms of the planning times for problems associated with drilling.

fallacy, this suggests that a procrastinator will suffer from H2. People in the unpacked condition will estimate longer

optimistically biased task completion time forecasts. Con- completion times for the drilling task.

versely, Buehler and Griffin (2003) discussed that there H3. All four groups will be affected by the planning fallacy.

may also be reason to believe that procrastinators may H4. Decision training will lessen susceptibility to the

be less inclined to optimistic bias—as Lay (1995) noted planning fallacy.

many procrastinators dwell on their past experiences of H5. Optimists will tend to estimate shorter times for

task completion time problems more readily than non- problems associated with drilling.

procrastinators, which could be interpreted as greater will- H6. Procrastinators will tend to estimate shorter comple-

ingness to adopt an outside perspective when estimating tion times for the drilling task.

completion times. Pychyl et al (2000) found that students

who scored highly on a procrastination scale did, in fact, METHODOLOGY

start their tasks later and spend less time on the task than Participants

a non-procrastinator. They were, however, able to predict

these actions in advance. Participants were 104 petroleum engineering students

and oil and gas industry professionals, 77 male and 23

Avoiding the planning fallacy female (with four failing to state their sex) with a mean

age of 25.7 years (Standard deviation [SD] = 9.4). These

As previously discussed, Buehler et al (1997) investi- were gathered as four separate groups: third year, fourth

gated the role of motivated reasoning in making completion year, masters, and industry. The groups differed in terms

predictions. The results showed that participants who had of their average industry experience from less than half a

received a speed incentive displayed greater optimistic year to more than 10 years. Participants from each group

bias in their completion predictions relative to participants were randomly assigned to either the packed or unpacked

without such an incentive. Another observation was that questionnaire condition. The summary statistics for each

participants who were provided with an accuracy incen- of these groups are given in Table 1.

SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10 APPEA Journal 2010 50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE—3

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. Begg

Materials and procedure groups and the relationships between our variables. NHST

includes a wide variety of statistical tests but linking all

Participants’ details were gathered using a survey de- of these is the calculation of a p-value, which indicates

livered in person (to the three student groups) or online the likelihood of seeing as large a difference between

(to the industry group). This requested the participant’s groups (or as strong a relationship between variables) as

age, sex, years of industry experience and asked whether observed in the data, by chance alone. That is, a p-value

they had received decision training or not (participants of .05 (conventionally written as p = .05), indicates that

were free to decide what constituted decision training and there is only a 5% chance of having found a relationship

thus we expected significant differences in what a ‘yes’ in as strong as the one in the data if there is, in truth, no such

response to this question might signify in practical terms). relationship. A p-value of .05 or lower is, by convention,

The questionnaire also included two personality scales, the accepted as the cut-off for concluding that there is, in fact,

Lay procrastination scale (LPS) to measure procrastination a statistically significant relationship in the data. We use

(Lay, 1986) and the revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) this convention throughout.

to measure optimism (Scheier et al, 1994), the summary While the analyses of primary interest are the com-

results of which are shown in Table 1. parisons between the different groups in our experiment,

Finally, participants were asked to estimate task comple- we have also included comparisons with an analogue in

tion times (in hours) for a hypothetical infill well described the form of the time breakdown of an offshore Louisiana

to them in general terms as follows: well (Bourgoyne et al, 1986) so as to ground our results

‘An oilfield is located offshore Louisiana in about against real-world values. Our task, however, excluded cer-

350 ft of water. The field contains four wells that are tain tasks incorporated into the analogue (such as casing

currently producing 1,000 bbl of oil and 18 MMSCF of placement) so the analogue times were adjusted to take

gas per day. Production is declining and it has been these differences into account. Table 2 shows the adjusted

decided to drill an infill well in order to improve pro- time estimates from the analogue well.

duction. The well is required to be drilled to 10,000 ft

drilling overbalance with mud. For this example, we RESULTS

will assume the well can be drilled straight to 10,000 ft

without the need for staged casing. The rig is already in Overview of data

place and ready to commence drilling. From other well Before analysing the data in terms of the hypotheses

data, the stratigraphy can be assumed to be reasonably regarding the effect of group and question form (packed or

homogeneous and consolidated. The well needs to be unpacked), a general overview of the dataset as a whole was

ready up to the point where casing could then be run desired in order to assess the strength of any relationships

if required.’ between the demographic variables and the personality

In the packed form of the questionnaire, seen by ap- measures. Preliminary assessment of the relationships be-

proximately half the participants, they were asked to make tween the variables generated a correlation matrix using

time estimates for the following tasks: drilling, tripping, ranked rather than raw data for the time estimates, as

rigging up and all other associated problems. In the un- the data were not normally distributed (time estimates,

packed version, by comparison, the all other associated both generally and in our data, tend to be exponentially

problems category was broken down into its individual distributed). This is included as Table 3.

components as follows: mud conditioning, well control op- Looking at Table 3, one sees, firstly, that the four time

erations, fishing operations, severe weather, rig repairs estimates (drilling, tripping, rigging and problems) are all

and logistic delays. related to one another with significant, positive, correla-

tions ranging from .39 to .68, p < .001. That is, people who

Data analysis and comparison tended to estimate longer times for one aspect of the task

also estimated longer times for the other three.

In all cases, we use null hypothesis significance testing Turning, secondly, to the personality variables (optimism

(NHST) to assess the strength of any differences between and procrastination), one sees limited impact of these on

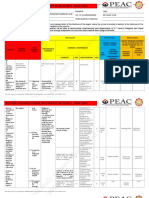

Table 1. Summary of group statistics—counts, means and SDs (in parentheses).

Group N Male Female Age Years of experience Procrastination Optimism

Third year 32 20 12 21.4 (2.9) 0.4 (1.4) 56.7 (10.4) 15.6 (2.4)

Fourth year 29 24 3 24.1 (7.4) 1.4 (4.9) 56.8 (13.6) 15.5 (3.9)

Masters 16 9 6 26.5 (5.4) 2.9 (3.1) 53.75 (10.7) 17.3 (2.7)

Industry 27 24 2 32.5 (14.0) 10.1 (13.9) 51.1 (8.7) 16.4 (2.5)

Note: the scores in the procrastination and optimism columns are the means and SDs of participants’ raw scores from the LPS and LOT-R tests described in the

materials and procedure section.

4—50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE APPEA Journal 2010 SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10

The planning fallacy in oil and gas decision making

the time estimates. Procrastination seems as if it may be problems.That is, older (more experienced) people tended

weakly related to the estimation of problem times, with to estimate longer times to complete the drilling, tripping

people inclined toward procrastination slightly more likely and rigging aspects of the described task but not for the

to estimate lengthier delays due to problems. This rela- problems.

tionship, however, while nearing statistical significance, Finally, we consider whether sex plays a role in time

p = .057, is very weak at r (102) = .19. Optimism, similarly, estimation or affects the personality variables. To assess

has only weak relationships with the time estimates, with this, we used a series of Mann-Whitney U-tests (non-par-

more optimistic people perhaps slightly more likely to ametric equivalents of independent samples t-tests that

estimate shorter times for problems, r (102) = .19, p = .059. allow comparisons to be made despite the fact that the

Thirdly, we consider the role of demographic variables variables we are considering are not normally distributed).

(age, experience and sex). Of these, only the first two are These found that males’ estimates of drilling and tripping

included in the correlation tables and one can see that times were significantly (or nearly so) longer than females’,

they are, unsurprisingly, very strongly related to one an- U = 648.5 and 708.5, p = .023 and .072, respectively. The

other, r (98) = .954, p <.001, and can, as such, be treated as strongest effect, however, was for age, with females being

measures of essentially the same thing. Strangely, though, significantly younger than the males, U = 568, p = .009.

it seems that age, rather than experience, has the stronger Given the relationships between age and time estimates

correlations with the time estimates, correlating positively described above, it seems likely that this effect accounts

and significantly with all of the time estimates except for the majority of the differences in time estimation be-

tween the sexes. As such, we do not consider males and

Table 2. Adjusted time breakdown from analogue well. females separately beyond this point.

Task Hours Time Fraction Effects of experimental conditions

Drilling 300 0.26 To assess the effect of the experimental conditions -

that the four groups would differ from one another and

Tripping 200 0.17

that the form on which the question was presented to

Rigging up 250 0.22 the participants (packed or unpacked) would affect their

time estimates—a series of eight 2x4 analysis of varianc-

All Associated Problems 400 0.35

es (ANOVAs) were run; one for each of the variables in

mud conditioning (145) (0.13) Table 3. In each case, given the knowledge that the time

estimates would violate the assumption of normality re-

well control operations (12) (0.01)

quired for a standard ANOVA, the analyses were run on

fishing operations (100) (0.09) rank-transformed data (Conover and Iman, 1981). These

analyses determine, for each of the variables of interest,

severe weather (97) (0.08) whether there is a difference between groups, or if it is

rig repair (20) (0.02)

caused by the question format, or some interaction between

these two possibilities. Summary statistics for each group’s

logisitic delays (26) (0.02) performance on the four time measures are shown in Table

4, divided by packing condition.

Total 1,150 1.00

Table 3. Correlations between demographic variables and ranked time estimates.

Drilling Tripping Rigging Problems Procrastination Optimism Age Experience

Drilling - .001 .001 .001 .798 .222 .037 .083

Tripping .68 - .001 .001 .597 .574 .001 .003

Rigging .61 .57 - .001 .297 .957 .016 .025

Problems .55 .39 .57 - .057 .059 .491 .617

Procrastination .03 -.05 .10 .19 - .154 .150 .305

Optimism -.12 .06 -.01 -.19 -.14 - .060 .053

Age .21 .32 .24 .07 -.14 .19 - .001

Experience .17 .29 .22 .05 -.10 .19 .95 -

Note: values in the bottom left triangle are the correlation coefficients while those in the top right are the corresponding p-values (two-tailed in all cases). Signifi-

cant relationships (p < .05) are indicated by bold entries. N = 104 in all cases except age and experience, N = 102, and the age-by-experience correlation N = 100.

SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10 APPEA Journal 2010 50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE—5

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. Begg

GROUP DIFFERENCES the time allocated to the other aspects of the overall task.

Looking at the data one sees that, in 10 of the 12 cases,

Differences between the groups were discovered for the time estimates for the non-problem aspects of the task

three of the variables shown in Table 1, with another ap- were reduced in the unpacked condition, which a sign test

proaching significance. Specifically, age, experience and indicates is significant (p = .003). That is, while the overall

rigging estimates differed significantly between the groups, time estimates tended to increase in the unpacked condi-

F(3, 92) = 9.59, 9.23 and 3.06, p < .001, .001 and p = .032, tion, this effect was counteracted, to some extent, by the

respectively. Post-hoc Bonferroni analyses confirmed that tendency of people to reduce their estimates of the other

the industry group differed significantly from the third aspects of the task. Interestingly, the two cases where this

year and fourth year groups in terms of age and from effect was not observed were in the estimates made by the

all three other groups in terms of experience—being, un- industry group (for tripping and rigging up).

surprisingly, older and more experienced than the three

student groups. The differences between groups’ rigging INTERACTION EFFECTS

estimates, by comparison, were accounted for the differ-

ence between the third year and fourth year groups—as No significant interactions between group and unpack-

was the near-significant difference in problem times, F(3, ing were observed in any of the eight ANOVAs. This can

92) = 2.44, p = .069. be seen in Figures 1 and 2, which depict the relationships

Apart from this, however, the groups were fairly homo- between group and unpacking condition for the two time

geneous, with no noticeable differences between their estimation variables where a significant effect was found

time estimates and none between their scores on the per- for either group or form (rigging and problems). That said,

sonality measures. given the limited sample size and loss of power resulting

from the necessary use of ranked data, it is possible that

EFFECT OF UNPACKING genuine, interaction effects simply have not been found.

Given this, there are patterns of results in Table 4 that

Differences between participants’ scores according to deserve comment. For example, the fact that the indus-

whether they had seen the packed or unpacked version of try group’s estimates of problems changed by more than

the question were also assessed via the ANOVAs described 200 hours between the packed and unpacked conditions

above. Only one of the eight ANOVAs showed a signifi- (the largest change of any group) might be indicative of a

cant result for unpacking—the one run for the estimates greater understanding of the nature of the problems given

of problem times. This found a highly significant effect, in the unpacked list but, if so, this highlights the dangers

with people who had seen the unpacked version making of the planning fallacy as the industry group’s estimates of

estimates of problem times that were significantly longer problem times in the packed condition were amongst the

than those of participants who saw the packed version of lowest—less than half that of the fourth year group. The

the question, F(1, 92) = 9.37, p =.003. This can be seen in implications of this are discussed in the effect of decision

the data in Table 4, where, in all four groups participants training section below.

seeing the unpacked version of the question made estimates

of problem times noticeably larger than their equivalents Effect of decision training

in the packed condition—an average of more than 100

hours difference across the four groups. In addition to the hypotheses regarding group differ-

An additional effect of unpacking can be seen in Table ences and the impact of unpacking condition, we were

4; unpacking the problem estimation task, while increasing also interested to see what impact decision training had

the time attributed to problems, also seemed to reduce on time estimates and, in particular, whether this would

Table 4. Mean (and SD) time estimates by group and packing condition.

Task Condition Third year Fourth year Masters Industry

Packed 285.3 (601.3) 345.6 (417.2) 228.6 (112.9) 398.4 (112.9)

Drilling

Unpacked 249.1 (492.3) 305.8 (209.4) 179.7 (210.7) 333.8 (126.2)

Packed 24.0 (28.6) 84.1 (185.0) 51.1 (45.0) 56.1 (24.4)

Tripping

Unpacked 20.9 (25.7) 78.6 (119.5) 36.6 (37.6) 61.1 (27.3)

Packed 22.3 (20.2) 139.0 (278.3) 51.4 (30.8) 70.4 (34.4)

Rigging up

Unpacked 20.4 (12.8) 112.5 (139.7) 77.4 (76.0) 74.2 (38.5)

Packed 50.3 (125.2) 139.8 (208.2) 93.1 (81.7) 65.7 (46.0)

Problems

Unpacked 113.4 (68.2) 270.9 (288.1) 161.4 (131.2) 267.1 (51.4)

Packed 381.9 (739.9) 708.5 (913.6) 424.3 (157.4) 590.7 (698.1)

Total

Unpacked 403.8 (563.4) 767.8 (544.2) 455.1 (379.9) 736.2 (616.5)

Packed 15 17 7 15

N

Unpacked 17 12 9 12

6—50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE APPEA Journal 2010 SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10

The planning fallacy in oil and gas decision making

have a differential impact on participants’ estimates of in age, experience and personality variables and ensured

problem time in the different conditions. To assess this, that the decision training referred to was uniform in its

we focussed on the differences between the third year and content (as all of the fourth years had undertaken decision

fourth year groups as these were judged most similar on our training in the same university course).

demographic variables but were sharply divided in terms To confirm that the two groups did not differ significantly

of whether they had received decision training—with none on any of the four predictor variables (age, experience,

of the third years and all but one of the fourth years having procrastination and optimism), independent samples t-tests

done so. This was preferred to a more general division of were conducted, finding no significant differences between

the sample into participants who had and had not received the groups—although the difference in age approached

decision training as it effectively controls for differences significance, t (59) = 1.81, p = .075, as one would expect

with groups from different year level cohorts.

The effect of decision training on predictions of prob-

lem time under each of the unpacking conditions was as-

sessed using a 2x2 ANOVA on the ranked problem time

data. This analysis found that both decision training and

the question format affected estimates of problem time

significantly and in the expected manner. That is, people

who had had decision training estimated greater lengths

of time for problems, F(1, 57) = 6.22, p = .016, as did people

who saw the unpacked version of the question, F(1, 57) =

24.53, p < .001.

No interaction between the two factors was observed,

however, as Figure 3 shows. That is, looking at Figure 3,

one can see that each of the factors (decision training and

unpacking condition) affects estimates of problem times

but each does so largely independently of one another—

as indicated by the fact that the lines are near parallel.

(NB: while plotting category values connected by lines

is technically incorrect, this is the traditional means of

demonstrating interaction effects in ANOVA results so

this convention is used here.)

More evidence for the potential benefits of decision

training was noted above—in the fact that the group with

Figure 1. Rigging estimates by group and unpacking condition.

Figure 3. Mean estimates of problem times by unpacking condition

Figure 2. Problem estimates by group and unpacking condition. and decision training.

SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10 APPEA Journal 2010 50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE—7

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. Begg

the highest estimates of problem time, in the packed condi- DISCUSSION

tion, was the fourth years. That is, having previously been

made aware of the packing/unpacking bias and its relevance

Overview

to the planning fallacy, this group made estimates for the The data presented above offer significant support for

packed category that were approximately double those a number of our hypotheses and shed some light on the

made by the remaining three groups. This, combined with remainder. The hypotheses are discussed individually be-

the observation made above regarding the strength of the low, in terms of the degree of support that the data offer

packing effect on estimates made by the industry group, for them and any possible confounds.

strongly argues for a benefit in providing such training.

HYPOTHESES

Comparison with analogue

Hypothesis 1 (H1): People in the unpacked condition will

As a final test of our participants’ estimates we com- estimate longer times for problems associated with drilling

pared their results, divided according to group and packing

condition, with the values calculated from the real world There is clear evidence that unpacking the problem

analogue to our problem. This test was included to avoid category into its constituent parts increases the estimates

the criticism that a manipulation, such as unpacking, that of total problem time made by our participants; this is

causes people to increase their time estimates is only useful observed both generally and in all four groups. Differences

if people are, prior to unpacking, underestimating. That between estimates made by participants in the packed

is, before claiming that unpacking reduces the planning and unpacked conditions varied from around 60 hours to

fallacy, we must demonstrate that people in fact commit more than 200 hours across the four groups.

the planning fallacy in the task we are using. Thus, differ-

ences between participants’ estimates and the real world Hypothesis 2 (H2): People in the unpacked condition will

analogue values are included as Table 5 so as to enable

estimate longer completion times for the drilling task

performance in our experimental conditions to be com-

pared to observed results from the real world. The data show that, both overall and within each group,

Looking at Table 5, perhaps the clearest result is that the people in the unpacked condition did, in fact, estimate

total estimates made by our participants are significantly longer completion times for the overall drilling task. The

less than the values from the analogue—by 382.2 hours difference between estimates in the packed and unpacked

in the best case and as much as 768.1 hours in the worst. conditions, however, ranged from relatively minor (~22

Of the other results, it seems that participants were fairly hours in the third year group) up to quite large (~145 hours

accurate in their estimates of drilling times but greatly in the industry group). Overall, the differences were not

underestimated the times for the other tasks relative to statistically significant but the pattern of results seems

the analogue. The largest errors, as would be expected, are fairly clear, with unpacking the problem category into

seen in the estimated problem times in the packed condi- its subcategories increasing the overall completion time

tion. Of the groups, the fourth year and industry groups estimates.

are clearly the best performers, with estimates hundreds The fact that this effect was not significant, however, de-

of hours closer to the observed values than those made serves some additional discussion. While there are sample

by the third year and masters groups. size considerations (as will be discussed in the limitations

Overall, for the 32 time estimate comparisons (group by section below), the main reason for this effect not reach-

task by condition) 28 show underestimation by participants ing statistical significance seems to relate to the way in

relative to the real-world base line. A sign test shows this which people react to estimation tasks like the one used

to be highly significant, p < .001, indicating that all of our herein. Specifically, it seems that people, while influenced

groups do seem to be falling victim to the planning fallacy by the unpacking to add weight to the problems category,

under both conditions. in some sense have a global estimate that they are divid-

Table 5. Difference between real world and estimated times by group and packing condition.

Task Condition Third year Fourth year Masters Industry

Packed -14.7 45.6 -71.4 98.4

Drilling

Unpacked -50.9 5.8 -120.3 33.8

Packed -176 -115.9 -148.9 -143.9

Tripping

Unpacked -179.1 -121.4 -163.4 -139.9

Packed -227.7 -111.0 -199.6 -179.6

Rigging up

Unpacked -229.6 -137.5 -172.6 -175.8

Packed -349.7 -260.2 -306.9 -334.3

Problems

Unpacked -286.6 -129.1 -238.6 -132.9

Packed -768.1 -441.5 -725.7 -559.3

Total

Unpacked -746.2 -382.2 -694.9 -413.8

8—50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE APPEA Journal 2010 SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10

The planning fallacy in oil and gas decision making

ing up amongst the available categories. Thus, in order to many of the industry personnel while having previously

increase the total time assigned to problems, they reduce taken decision training may no longer have retained any

the weight assigned to the other categories. While this benefit from it.

correction is not enough to undo the effect of unpacking

entirely, it is enough to reduce the difference between the Hypothesis 5 (H5): Optimists will tend to estimate shorter

packed and unpacked estimates to a point where statistical

significance is harder to obtain given our samples sizes

times for problems associated with drilling

and statistical tests. The relationship between individual optimism scores

and estimates of problem time in the data were weak but

Hypothesis 3 (H3): All four groups will be affected by the the correlation observed between these two variables was

planning fallacy in the predicted direction, r (102) = -0.19, and approached

significance, p =.059, when considered as a two-tailed test

While H1 and H2 refer specifically to the effect of pack- (that is, testing for a difference in either direction). Given

ing/unpacking, H3 refers, instead, to whether the groups are the fact that our hypothesis predicts the direction of the

seen to display the planning fallacy—that is, whether their relationship, however, we can conclude that the effect

estimates are lower than the true time taken to complete is significant if considered as a one-tailed test, p = .030

the task under discussion. Thus the relevant results are (half the two-tailed probability). That said, the observed

those comparing participants’ estimates with the real-world relationship is very weak—a correlation of -0.19 indicat-

data; and this comparison supports the hypothesis. That ing that one variable explains ~3.6% of the variance in

is, both overall and considering each component sepa- the other. While it is possible that the correlation would

rately, people tended to underestimate times relative to be increased if we considered a broader cross-section of

the real-world baseline. In general, then, it seems safe people (with a commensurately wider range of optimism

to conclude (bearing in mind the caveats regarding our scores), the uniformity of our sample across groups seems

analogue discussed below) that our participants were af- to indicate that our sample is fairly representative of the

fected by the planning fallacy, regardless of which group oil industry itself and thus one should probably conclude

or condition they were in. that optimism is not going to prove a useful predictor of

estimates of problem times.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Decision training will lessen

susceptibility to the planning fallacy Hypothesis 6 (H6): Procrastinators will tend to estimate

shorter completion times for the drilling task

The comparison between the third and fourth year

groups described above tested for the impact of decision By comparison, no statistical evidence was found linking

training on the strength of the planning fallacy and un- individuals’ procrastination scores with the overall time

packing effect.The results indicated that decision training estimates for the drilling task as a whole. The only result

did, in fact, significantly reduce the effect of the planning that approached significance was between procrastination

fallacy—with the fourth year group making estimates that score and problem time, r (102) = 0.19, p = .057, indicating

were significantly longer (and thus closer to the real-world that people who scored highly on the procrastination scale

values) than those of the third year group—in every case actually tended to predict more time for problems. This

(i.e., each combination of condition and task). Statistical relationship is in the opposite direction to that predicted

analyses also, however, indicated that both groups were and might be interpreted as procrastinators being adept

affected by the unpacking manipulation. That is, while at generating reasons to put off a task—the assumption

participants with decision training provided estimates being that potential problems are a reason not to start a

of problem time in the packed condition that were sig- task. That said, as was the case with optimism, the strength

nificantly better than those made by participants without of this relationship is very weak and thus its potential as

decision training, both groups reacted in the same way a predictor of people’s behaviour is limited.

to the Problem task being unpacked into its constituent

parts—by increasing the amount of time allocated to it. Implications

Thus, the conclusion is that decision training has a sepa-

rate effect from the unpacking effect and that both can Overall, the results have clear implications for oil and gas

be used to reduce susceptibility to the planning fallacy. decision making. A primary observation is that oil industry

The fact that the industry group, who had the second personnel, making decisions of a type they can reasonably

highest rate of decision training, showed no such benefit be expected to understand, are subject to the planning

in terms of their packed condition estimates of time does, fallacy—tending to make estimates of completion times

however, need some explanation. A possible reason is that that are far shorter than real-world data indicates. This

the decision training referred to (remembering that this was seen in all four of our groups, indicating that this is a

group’s training was not uniform) may not have included general tendency not removed by greater experience—an

specific reference to the planning fallacy. Another likely observation reinforced by the fact that the group least af-

reason is that the benefit of decision training has been fected by the planning fallacy was the fourth year group

observed to erode over time (Welsh et al, 2005) and thus who had the second least industry experience of the groups.

SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10 APPEA Journal 2010 50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE—9

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. Begg

Equally important are the twin observations that account for sample size in determining p-values—it is pos-

both decision training and utilisation of the unpacking sible that this may have resulted in false negatives, where

strategy reduce the strength of the planning fallacy. The we have failed to find an effect that does exist. Looking at

clear difference between the otherwise similar third and our data, it seems likely, for example, that a more powerful

fourth year groups seems to strongly support the idea that (in statistical terms) analysis would probably have found

knowledge of the planning fallacy (and potential mecha- a statistically significant interaction between group and

nisms for reducing it) does provide a benefit in terms of packing condition whereby the industry group was more

reduced susceptibility to this bias. Similarly, the results strongly affected by the unpacking of the problem category.

clearly indicate that unpacking a general category into its Similarly, it seems likely that somewhat larger sample

constituent parts helps people reduce the impact of the sizes would have confirmed the effect of optimism (H5)

planning fallacy on their estimates (as argued by Kruger and procrastination (H6) on time estimation as discussed

and Evans, 2004). above (although the effect size would remain very small)

Thus, it would seem to be in the interests of the industry and confirmed an overall effect of packing on total time

to institute decision training to make personnel aware of estimates (H2).

the planning fallacy, its effect and possible consequences. A second problem lies in the distribution of the data

Additional training in specific debiasing strategies such and the types of NHST testing that this necessitated. As

as unpacking general categories would further reduce the noted throughout, time estimation data is not normally

effect of the planning fallacy and greatly improve industry distributed (a common assumption for parametric NHST

forecasts. This is of particular importance given the pat- tests) and so non-parametric equivalents had to be used.

tern of results described above—where unpacking had These tests, while avoiding the assumptions about data

its greatest effect on the estimates made by the industry distributions, have less statistical power and thus are less

group. This implies that, while industry experience does likely to find a significant difference than their parametric

not help avoid the planning fallacy when general catego- equivalents.Thus, combined with the sample size considera-

ries are presented, once an unpacking process has been tions noted above, the necessity of using non-parametric

initiated, industry experience allows more appropriate tests increases the likelihood of false negatives.

time estimates to be generated for these subcategories. A third, potential problem lies in our analogous data.

That is, the benefit of unpacking will be greatest for those While this was taken from a real-world example (that was

people with greater knowledge to draw upon. used to construct our scenario), in order to produce a work-

A final observation regarding the implications of the able question for our participants there were a number

findings described above relates to the global nature of of differences between the real well and the hypotheti-

time estimates discovered herein. The fact that people’s cal one in terms of the included tasks. As such, we had

estimates of problems increased when this category was to adjust the analogue’s times to account for these dif-

unpacked was predictable, but the observation that this ferences. Thus, while the results described above can be

often resulted in a reduction in the time estimates relating considered indicative of likely differences between real

to other aspects of the overall task has implications for the and estimated times, they certainly could not be argued to

use of unpacking as a debiasing technique for the planning measure such precisely. Additionally, the analogue, while

fallacy. Clearly, this implies that people may have a global chosen to be representative of the situation described to

impression of how long the entire task will take and then participants, represents a single observation from the real

divide this among the available categories with the result world rather than an average across a variety of similar

that unpacking one category reduces the weight available wells. As such, it may be that this well is less typical than

to the other categories. That said, this global impression is, we would hope and that similar wells might take more or

itself, amenable to alteration, as in the unpacked condition less time on average than indicated by this data; or that

we did still see an overall increase in time estimates for the the breakdown of time per task is unusual.

complete task. A reasonable assumption might thus be that Finally, we must consider the fact that the estimation

the global impression is formed from a combination of a task used herein, while based on real data, required our

person’s knowledge and the sheer number of categories in participants to make their estimates based on far less data

need of estimates. Thus, while unpacking a single category than they would, in the course of their jobs, have available

tends to reduce the weight assigned to other categories, to them. The idea that greater certainty about the specific

this also increases the global time estimate. This effect details of the well in question would reduce susceptibility

must, clearly, be borne in mind when undertaking actions to the planning fallacy, however, is questionable at best.

designed to reduce the planning fallacy. If anything, given Buehler et al’s (1994) inside/outside

distinction, one would, in fact, expect the opposite—with

Limitations more specific details leading to an increase in the strength

of the planning fallacy.

As is always the case with laboratory research, there are

a number of caveats that must be kept in mind when exam- Future research

ining our results. Firstly, we must consider the relatively

small numbers of participants in our groups (the masters Our findings point to a number of potentially fruit-

group in particular). While this is unlikely to have resulted ful lines of research regarding the planning fallacy. For

in any false positives in our statistics—as NHST techniques example, the idea of initial global estimates and their

10—50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE APPEA Journal 2010 SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10

The planning fallacy in oil and gas decision making

dependence on the number of categories made available time predictions. Organizational Behavior and Human

to a person during an estimation task is one that seems Decision Processes, 92, 80–90.

amenable to experimental confirmation. That is, we could

test the extent to which varying the initial number of cat- BUEHLER, R., GRIFFIN, D. AND MACDONALD, H.,

egories affects an individual’s overall estimates of time, 1997—The role of motivated reasoning in optimistic time

cost, etcetera. predictions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,

Additional work with a larger sample could also estab- 23, 238–47.

lish whether the patterns of results discussed above that

failed to reach statistical significance do, in fact, reflect BUEHLER, R., GRIFFIN, D. AND ROSS, M., 1994—Explor-

underlying relationships; it is possible that we simply ing the “planning fallacy”: why people underestimate their

failed to find such relationships due to limited statistical task completion times. Journal of Personality and Social

power resulting from our sample sizes and use of non- Psychology, 67, 366–81.

parametric tests. With a larger, industry sample, it might

also be possible to divide the sample into groups accord- CARROLL, J.B., 1993—Human cognitive abilities: a survey

ing to their level of experience and thereby tease out, in of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

greater detail, the effects of experience on susceptibility University Press.

to the planning fallacy.

Finally, while we found no clear evidence of impact of CONOVER, W.J. AND IMAN, R.L., 1981—Rank transforma-

personal traits on susceptibility to the planning fallacy or tions as a bridge between parametric and nonparametric

debiasing through unpacking of categories, it should be statistics. The American Statistician, 35 (3), 124–9.

noted that our analyses, in terms of individual differences,

was extremely limited and it may be worthwhile consider- COSTA, P.T.J. AND MCCRAE, R.R., 1992—NEO PI-R

ing the impact of a wider range of individual traits. For Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assess-

example, it might be effective to use the Big 5 personality ment Resources.

measures from the NEO PI-R (Costa and McCrae, 1992),

or to assess the relationship between the planning fallacy FERRARI, J.R., JOHNSON, J.L. AND MCCOWN, W.G.,

and differences in specific intelligence measures such as 1995—Procrastination and task avoidance. New York, NY:

those described by the Cattell-Horn-Carroll model of in- Plenum Press.

telligence (Carroll, 1993).

FISCHHOFF, B., SLOVIC, P. AND LICHTENSTEIN, S.,

Conclusions 1978—Fault trees: sensitivity of estimated failure probabil-

itiies to problem representation. Journal of Experimental

Despite the limitations discussed above, it seems clear Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 4, 330–44.

that our experimental results support the idea that oil and

gas industry personnel are affected by the planning fallacy GOODE, P., 2002—Connecting with the reservoir. Austra-

when estimating completion times and that this effect can lian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association

be ameliorated by both: training in decision making that Journal, 42 (2), 50–5.

makes clear how and why the planning fallacy occurs; and

specific debiasing through unpacking of general categories KAHNEMAN, D. AND TVERSKY, A., 1979—Intuitive pre-

into subcategories. Uptake of this information offers the dictions: Biases and corrective procedures. TIMS Studies

potential to greatly improve the accuracy of forecasting in Managment Science, 12, 313–27.

within the industry, preventing adverse outcomes in the

form of unexpected delays and cost growth. KOOLE, S. AND SPIJKER, M., 2000—Overcoming the plan-

Specifically, the accuracy of estimates of costs, time, ning fallacy through willpower: effects of implementation

etcetera, are likely to be greatly improved if a project’s intentions on actual and predicted task-completion times.

constituents are clearly enumerated prior to any estimates European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 873–88.

being made—rather than relying on a simple, mental sce-

nario of how the project seems likely to unfold—as it has KRUGER, J. AND EVANS, M., 2004—If you don’t want to be

been clearly demonstrated that outcomes and possibilities late, enumerate: Unpacking reduces the planning fallacy.

that are out of sight are also out of mind. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 586–98.

REFERENCES KUNDA, Z., 1990—The case for motivated reasoning.

Psychological Bulletin, 108 (3), 480–98.

BOURGOYNE, A.T.J., CHENEVERT, M.E., MILLHEIM,

K.K. AND YOUNG, F.S.J., 1986—Applied Drilling Technol- LAY, C., 1986—At last, my research article on procrastina-

ogy. Richardson, TX: SPE. tion. Journal of Research in Personality, 20, 474–95.

BUEHLER, R. AND GRIFFIN, D., 2003—Planning, person- LAY, C., 1995—Trait procrastination, agitation, dejection

ality and prediction: the role of future focus in optimistic and self-discrepancy. Motivation and Emotion, 18, 269–84.

SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10 APPEA Journal 2010 50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE—11

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. Begg

LONG, S., 2005—Multiplex loses money to Wembley

Stadium Project. ABC Local Radio National. Accessed 10

October 2009. <http://www.abc.net.au/am/content/2005/

s1380951.htm>

Merrow, E., 2003—Mega-field developments require spe-

cial tactics, risk management. Offshore, 63 (June), 90–6.

NEWENDORP, P.D. AND SCHUYLER, J., 2000—Decision

Analysis for Petroleum Exploration. Aurora, Colorado:

Planning Press.

PEZZO, S.P., PEZZO, M.V. AND STONE, E.R, 2006—The

social implications of planning: how public predictions

bias future plans. Journal of Experimental Social Psychol-

ogy, 42, 221–7.

PYCHYL, T.A., MORIN, R.W. AND SALMON, B.R., 2000—

Procrastination and the planning fallacy: an exmaination

of the study habits of university students. Journal of Social

Behavior and Personality, 15 (5), 135–50.

SCHEIER, M.F., CARVER, C.S. AND BRIDGES, M.W.,

1994—Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and

trait anxiety, self mastery and self-esteem): a reevaluation

of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 67, 1,063–78.

TVERSKY, A. AND KOEHLER, D.J., 1994—Support Theory:

a nonextensional representation of subjective probability.

Preference, Belief and Similarity: Selected Writings.

WELSH, M.B., BRATVOLD, R.B. AND BEGG, S.H., 2005—

SPE 96423—Cognitive biases in the petroleum industry:

impact and remediation. Proceedings of the Society of

Petroleum Engineers 81st Annual Technical Conference

and Exhibition.

12—50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE APPEA Journal 2010 SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10

The planning fallacy in oil and gas decision making

THE AUTHORS

Matthew B.Welsh has a BA(Hons) in Hugh Ringwood completed his

philosophy and a BSc(Hons) and PhD BPetEng (Hons) at the Australian

in psychology, all from the University School of Petroleum in 2009. He is

of Adelaide. He has been employed undertaking a junior field engineer

as a research fellow in the Improved internship with Baker Hughes-Baker

Business Performance Group at the Atlas. Hugh is also employed as a

Australian School of Petroleum for research assistant at the University

the past six years, conducting research of Adelaide, Australia, as part of the

focussing on the psychological aspects Lake Eyre Basin Analogues Research

of decision making and the impact that these can have on the Group (LEBARG). Member: SPE, PESA and Engineers Australia.

accuracy of forecasts and thus economic outcomes. Member:

SPE, Cognitive Science Society and Association for Psychologi-

Stephen (Steve) H. Begg has a

cal Science.

BSc and PhD in geophysics from the

University of Reading, England. He is

Nigel Rees completed his BPetEng a Professor of Petroleum Engineering

(Hons) in geology and geophysics at and Management at the University of

the Australian School of Petroleum in Adelaide, Australia, focussing on deci-

2009. He is employed as a research sion making under uncertainty, asset

assistant for the Lake Eyre Basin and portfolio economic evaluations,

Analogues Research Group conduct- and psychological factors that impact

ing research on the geomorphology these. Formerly, he was the director of strategic planning and

and sedimentology of large mud- decision science with Landmark Graphics. Prior to that he held

dominated rivers and floodplains in the a variety of senior operational engineering and geo-science

Channel Country, Central Australia. Nigel is also employed roles for BP Exploration, and was a reservoir characterisation

as a junior field engineer with Baker Atlas. Member: SPE, researcher and manager for BP Research. Steve has been an

Engineers Australia and PESA. SPE Distinguished Lecturer and has Chaired several SPE Forums

and Advanced Technology Workshops related to his areas of

expertise. Member: SPE and AAPG.

SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10 APPEA Journal 2010 50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE—13

M. B. Welsh, N. L. Rees, H. A. Ringwood and S. H. Begg

14—50th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE APPEA Journal 2010 SECOND PROOF—WELSH 27 JAN 10

View publication stats

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Many Faces of ImpulsivityDocument6 pagesThe Many Faces of ImpulsivityTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- System Dynamics As Model-Based Theory BuildingDocument19 pagesSystem Dynamics As Model-Based Theory BuildingTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- A Definition of TheoryDocument25 pagesA Definition of TheoryKim Kevin Sadile AveriaNo ratings yet

- The Dunning-Kruger EffectDocument50 pagesThe Dunning-Kruger EffectZai RodríguezNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0272696315000595 Main PDFDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0272696315000595 Main PDFAnhNo ratings yet

- Using Cognitive and Causal Modelling To Develop A Theoretical Framework For Implementing Innovative PracticesDocument15 pagesUsing Cognitive and Causal Modelling To Develop A Theoretical Framework For Implementing Innovative PracticesTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Managing The Unexpected in MegaprojectsDocument22 pagesManaging The Unexpected in MegaprojectsTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study ResearchDocument24 pagesThe Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study ResearchTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- The Law of Regression To The TailDocument5 pagesThe Law of Regression To The TailTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Effect of Project Complexity On Cost and Schedule Performance in Transportation ProjectsDocument17 pagesEffect of Project Complexity On Cost and Schedule Performance in Transportation ProjectsTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Holistic Appraisal of Value Engineering in Construction in United StatesDocument5 pagesHolistic Appraisal of Value Engineering in Construction in United StatesTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- What Is QCA PDFDocument19 pagesWhat Is QCA PDFauladecomunicacaoNo ratings yet

- Design and Build Defined: Samir BoudjabeurDocument10 pagesDesign and Build Defined: Samir BoudjabeurTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study ResearchDocument24 pagesThe Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study ResearchTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- What Is QCA PDFDocument19 pagesWhat Is QCA PDFauladecomunicacaoNo ratings yet

- Theory Testing in Social ResearchDocument28 pagesTheory Testing in Social ResearchTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Research Guidelines For The Delphi SurveyDocument8 pagesResearch Guidelines For The Delphi SurveyTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Golafshani - Understanding Reliability and Validity in Qualitative ResearchDocument10 pagesGolafshani - Understanding Reliability and Validity in Qualitative ResearchWilliam MamudiNo ratings yet

- The Evaluation of Complex Infrastructure Projects - A Guide To Qualitative Comparative AnalysisDocument49 pagesThe Evaluation of Complex Infrastructure Projects - A Guide To Qualitative Comparative AnalysisTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Characterising and Justifying Sample Size Sufficiency in Interview-Based StudiesDocument18 pagesCharacterising and Justifying Sample Size Sufficiency in Interview-Based StudiesTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Confusing Categories and ThemesDocument2 pagesConfusing Categories and ThemesTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Theory Testing Using Case Studies - Vol 12-Issue1-Article335 PDFDocument9 pagesTheory Testing Using Case Studies - Vol 12-Issue1-Article335 PDFTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- The Logic of Small Samples in Interview-Based Qualitative ResearchDocument17 pagesThe Logic of Small Samples in Interview-Based Qualitative ResearchTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Themes, Theories, and ModelsDocument7 pagesThemes, Theories, and ModelsTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Theme Development in Qualitative Content Analysis and Thematic AnalysisDocument12 pagesTheme Development in Qualitative Content Analysis and Thematic AnalysisTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- The Online Survey As A Qualitative Research ToolDocument15 pagesThe Online Survey As A Qualitative Research ToolTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- CIMA Business Economics Study Text PDFDocument489 pagesCIMA Business Economics Study Text PDFSimon Chawinga100% (11)

- Cima BPP Learning Text EcoDocument241 pagesCima BPP Learning Text EcoSunil KakkarNo ratings yet

- C03 Study Text - BPPDocument421 pagesC03 Study Text - BPPTinh Linh0% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Lessons From Good Language Learner Part2 ContentsDocument3 pagesLessons From Good Language Learner Part2 ContentsMegabiteUQNo ratings yet

- Income Certificate Format - 2021Document1 pageIncome Certificate Format - 2021Faltu Ka jhamlqNo ratings yet

- Laoang Elementary School School Boy Scout Action Plan Objectives Activities Time Frame Persons Involve Resources NeededDocument3 pagesLaoang Elementary School School Boy Scout Action Plan Objectives Activities Time Frame Persons Involve Resources NeededMillie Lagonilla100% (5)

- Advanced Pharmaceutical Engineering (Adpharming) : Accreditation Course AimsDocument2 pagesAdvanced Pharmaceutical Engineering (Adpharming) : Accreditation Course AimsJohn AcidNo ratings yet

- VWR Traceable 300-Memory StopwatchDocument1 pageVWR Traceable 300-Memory Stopwatchlusoegyi 1919No ratings yet

- Association of Guidance Service and The Development of Individual Domains Among Tertiary StudentsDocument10 pagesAssociation of Guidance Service and The Development of Individual Domains Among Tertiary StudentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Learning - Module 3Document171 pagesFacilitating Learning - Module 3Rema MandaNo ratings yet

- Visual Literacy MatrixDocument2 pagesVisual Literacy MatrixernsteinsNo ratings yet

- AQA GCSE Maths Foundation Paper 1 Mark Scheme November 2022Document30 pagesAQA GCSE Maths Foundation Paper 1 Mark Scheme November 2022CCSC124-Soham MaityNo ratings yet

- Artikel Bahasa InggrisDocument16 pagesArtikel Bahasa InggrisRizalah Karomatul MaghfirohNo ratings yet

- Mark Scheme Summer 2008: IGCSE Mathematics (4400)Document46 pagesMark Scheme Summer 2008: IGCSE Mathematics (4400)Tammachat DumrongjakNo ratings yet

- What Is Applied Linguistics?: WWW - Le.ac - Uk 1Document2 pagesWhat Is Applied Linguistics?: WWW - Le.ac - Uk 1Ngô Xuân ThủyNo ratings yet

- DDA Assistant DirectorDocument28 pagesDDA Assistant DirectorAnshuman SinghNo ratings yet

- Kota Krishna Chaitanya - ResumeDocument4 pagesKota Krishna Chaitanya - Resumexiaomi giaNo ratings yet

- Ib Business Management Syllabus 1Document4 pagesIb Business Management Syllabus 1api-244595553No ratings yet

- Tablante, Caesar Cyril L.-UpdDocument1 pageTablante, Caesar Cyril L.-UpdCaesar Cyril TablanteNo ratings yet

- Edgar G. Sanchez, SGC Chairperson Rev. Ronald Melody, BarangayDocument3 pagesEdgar G. Sanchez, SGC Chairperson Rev. Ronald Melody, BarangayJick OctavioNo ratings yet

- EFA - Module 2 r1Document57 pagesEFA - Module 2 r1Jerry CañeroNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence Applied To Software TestingDocument7 pagesArtificial Intelligence Applied To Software TestingFaizal AzmanNo ratings yet

- Adilabad Voter ListDocument645 pagesAdilabad Voter Listsamaritan10167% (3)

- Hypothesis Test - Difference in MeansDocument4 pagesHypothesis Test - Difference in Meansr01852009paNo ratings yet

- List of TextbooksDocument5 pagesList of TextbooksESPORTS GAMING ZONENo ratings yet

- Strategy and Strategic-ConvertiDocument28 pagesStrategy and Strategic-Convertifarouk federerNo ratings yet

- Olugbenga's CV EngineerDocument2 pagesOlugbenga's CV EngineerSanni Tajudeen OlugbengaNo ratings yet

- Supa TomlinDocument33 pagesSupa TomlinDiya JosephNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan For Grade 7 Final DemoDocument9 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan For Grade 7 Final DemoEljean LaclacNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was Shared Via: Flexible Instructional Delivery Plan (Fidp) 2020-2021Document5 pagesThis Study Resource Was Shared Via: Flexible Instructional Delivery Plan (Fidp) 2020-2021Sa Le HaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Welding API 577 Capter 7Document12 pagesIntroduction To Welding API 577 Capter 7Edo Destrada100% (1)

- Spotting Error RulesDocument2 pagesSpotting Error RulesMohanshyamNo ratings yet

- Research Methods: Content Analysis Field ResearchDocument30 pagesResearch Methods: Content Analysis Field ResearchBeytullah ErdoğanNo ratings yet