Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ellis - 2018 - Assessment and Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - Revisión

Ellis - 2018 - Assessment and Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - Revisión

Uploaded by

Emmanuel Domínguez RosalesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ellis - 2018 - Assessment and Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - Revisión

Ellis - 2018 - Assessment and Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - Revisión

Uploaded by

Emmanuel Domínguez RosalesCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment REVIEW ARTICLE

and Management of C O N T I N U UM A U D I O

I NT E R V I E W A V A I L AB L E

ONLINE

Posttraumatic Stress

Disorder S U P P L E M E N T A L D I G I T AL

C O N T E NT ( S D C )

A V AI L A B L E O N L I N E

By Janet Ellis, MBBChir, MD, FRCPC; Ari Zaretsky, MD, FRCPC

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: The goal of this article is to increase clinicians’ understanding of

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and improve skills in assessing risk for

and diagnosing PTSD. The importance and sequelae of lifetime trauma

burden are discussed, with reference to trends in prevention, early

intervention, and treatment.

RECENT FINDINGS: PTSD has different clinical phenotypes, which are

reflected in the changes in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria. PTSD is almost always

complicated by comorbidity. Treatment requires a multimodal approach,

usually including medication, different therapeutic techniques, and

management of comorbidity. Interest is growing in the neurobiology of

childhood survivors of trauma, intergenerational transmission of trauma,

and long-term impact of trauma on physical health. Mitigation of the risk of

PTSD pretrauma in the military and first responders is gaining momentum,

given concerns about the cost and disability associated with PTSD. Interest

is also growing in screening for PTSD in medical populations, with evidence

of improved clinical outcomes. Preliminary research supports the

treatment of PTSD with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. CITE AS:

CONTINUUM (MINNEAP MINN)

SUMMARY: PTSD is a trauma-related disorder with features of fear and 2018;24(3, BEHAVIORAL NEUROLOGY

AND PSYCHIATRY):873–892.

negative thinking about the trauma and the future. Untreated, it leads to

ongoing disruption of life due to avoidance, impaired vocational and social Address correspondence to

functioning, and other symptoms, depending on the phenotype. Despite a Dr Janet Ellis, 2075 Bayview Ave,

theoretical understanding of underlying mechanisms, PTSD remains Toronto, Ontario M4N 3M5,

Canada, janet.ellis@

challenging to treat, although evidence exists for benefit of pharmacologic sunnybrook.ca.

agents and trauma-focused therapies. A need still remains for treatments

that are more effective and efficient, with faster onset. RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE:

Drs Ellis and Zaretsky report no

disclosures.

INTRODUCTION UNLABELED USE OF

W

PRODUCTS/INVESTIGATIONAL

itnessed or experienced traumatic events may include war, USE DISCLOSURE:

violence, natural disaster, acute physical trauma, unexpected Drs Ellis and Zaretsky report

or unnatural death of a loved one, bullying, and physical no disclosures.

illness. Most people will have some symptoms of acute stress © 2018 American Academy

disorder after a traumatic event, but most will recover. of Neurology.

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 873

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a trauma-related syndrome of chronic

distress, with dissociative features, including reexperiencing of the trauma, mood

and cognitive changes, hyperarousal, and avoidance.1 It is associated with personal

chaos; an impaired sense of cohesion; distress; withdrawal from hobbies, work,

and social activities; a poor quality of life; and increased health care utilization.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Between 10% and 50% of people who have had exposure to a life-threatening

trauma will develop persisting symptoms of PTSD.2,3 The lifetime prevalence of

PTSD varies by the diagnostic system used, gender, country, culture, values, and

exposure to war or crime-related trauma.4 While more exposure to trauma occurs

in lower-income countries compared to higher-income countries, the prevalence

of PTSD is fairly consistent, possibly implying a capacity to adapt to a level of

expected trauma. The exception to this is in postconflict zones, where the prevalence

of PTSD is highest,5 highlighting the increased risk of PTSD with interpersonal

violence. A 2013 study found that 89.7% of 2953 US adults had exposure to at least one

traumatic event and that exposure to multiple traumatic events was the norm.6 A

2017 systematic review of over 7 million primary care patients found a median

point prevalence of PTSD of 12.5% and of 24.5% across studies in veterans.7

Wittchen and colleagues8 found a range of lifetime prevalence of 0.56% to 6.67%

across European countries, with the highest prevalence in Croatia.

CONSEQUENCES OF POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Exposure to a traumatic event and the duration of PTSD increase the risk

of developing chronic physical conditions, emphasizing the importance of

prevention and intervention.9 An increased risk of hypertension, ischemic heart

disease, obesity, and dementia has been found in those with a high lifetime

burden of trauma.10 Some emerging evidence indicates that overall trauma load

and PTSD increase the risk of later-life cognitive decline.11 PTSD and depression

are strongly associated, and both should be treated to improve outcome. Eating

disorders are another common comorbidity, with reported trauma rates and

PTSD varying from 12% to 45%.12,13

DIAGNOSIS

Since some of the symptoms of PTSD are outside usual experience and,

furthermore, patients are generally not forthcoming about their symptoms

owing to avoidance, it is especially important for clinicians to become familiar

with and understand the diagnostic criteria and experience of PTSD. The

overriding experience of PTSD is that of living in fear and avoidance of

trauma-related triggers.

It is vital to recognize PTSD symptoms before planning treatment for any

mental health issue after a traumatic event. It is important to assess for PTSD

without inadvertently causing repeated trauma. Simply asking the patient to

recount the trauma may lead to a dissociative flashback, distress, shutdown of

any further history, a rupture in the therapeutic relationship, and possibly refusal

to return to treatment. A traumatic event should lead a clinician to conduct a

focused screen for further vulnerability and relevant diagnostic criteria in a

deliberate probe for symptoms rather than asking the patient to recount the trauma.

Patients may require stabilization; out-of-control substance use, unstable

living situation, and untreated comorbidity should all be addressed as much as

874 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

possible before starting active trauma therapy. The patient needs to develop KEY POINTS

skills in self-calming (breathing, visualization, or relaxation exercises when

● Posttraumatic stress

dysregulated) and grounding (the ability to reconnect with the present by disorder is a trauma-related

refocusing on sensory information in the present). After stabilization, specialized syndrome of chronic

parallel treatments for both PTSD and comorbid conditions (eg, depression, distress, reexperiencing the

anxiety, substance use) should be undertaken. trauma, dissociative

features with mood and

Pitfalls for clinicians when assessing patients with PTSD include

cognitive changes,

underestimating the distress or impact of the traumatic event (eg, the meaning or hyperarousal, and

subjective experience of a migraine14 or intensive care unit admission); failing avoidance.

to recognize the hidden face of PTSD in a complicated comorbid clinical picture;

and feeling frustrated with such patients as they are prone to unreliable ● Between 10% and 50%

of people who have

follow-up because of avoidance: “I’ll talk about anything else!” had exposure to a life-

PTSD is extremely disruptive to patients, who may not identify the problem as threatening trauma will

PTSD, simply believing that they are not coping. Patients with PTSD often say: develop persistent

“I do not know what this is, but I am not myself.” Many patients immediately symptoms of posttraumatic

stress disorder.

recognize the phrase “living in fear” as descriptive of how they feel, but they

generally do not put this into words themselves. The profound avoidance ● A traumatic event should

associated with PTSD can impact the therapeutic alliance, causing impatience in lead a clinician to conduct a

the clinician who may be faced with the paradox of a patient who is desperately focused screen for further

vulnerability and relevant

seeking help, yet misses appointments and does not follow through on taking

symptoms.

medications or doing homework.

● Pitfalls for clinicians

Identifying Those at Risk in the Clinical Environment when diagnosing patients

Health professionals often fail to recognize illness-related PTSD, apart from in with posttraumatic stress

disorder include

patients who have experienced acute physical trauma or burns. An increasing misdiagnosing the trauma

literature exists on the prevalence and impact of PTSD in patients with human (eg, underestimating the

immunodeficiency (HIV) and cancer and in patients who have experienced impact of an experience of a

childbirth or a stroke, been in intensive care, received an organ transplant, or had migraine or intensive care

unit admission) and failing to

cardiac surgery. recognize the hidden face of

PTSD is more likely to result from interpersonal violence than a natural posttraumatic stress

disaster.15 A higher risk of PTSD occurs with extended exposure to danger, disorder in a complicated

serious injury, dissociation during the event, or the loss of a loved one during the comorbid clinical picture.

traumatic event. The latter, if combined with PTSD, may result in an inability to

● Individual vulnerability to

grieve as the death is a reminder of the trauma.16 These survivors remain in posttraumatic stress

limbo, living in a hypervigilant fearful state with PTSD and without the capacity disorder includes a past

to deal with their complicated (avoided) grief, sometimes for years. Individual history of trauma, any

psychiatric disorder, and

vulnerability to PTSD includes a past history of trauma, any psychiatric disorder,

low social support.

and low social support. The way patients construe the cause of the trauma and

their posttrauma worldview should be carefully ascertained, since self-blame

(eg, “I should not have been walking in the dark”) and blanket negative

assumptions (eg, “I cannot keep myself safe,” “My life has been ruined by this

event”) predict and maintain PTSD.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

Diagnostic Criteria

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth

Edition (DSM-5),17 a diagnosis of PTSD can only be made 1 month after exposure

to at least one traumatic event. PTSD may also have a delayed onset of 6 months

or more after the event. DSM-5 changed the classification of acute stress disorder

and PTSD from anxiety disorders to trauma-related disorders, reflecting that an

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 875

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

KEY POINTS external traumatic event is required for the illness to develop. A DSM-5 diagnosis

of PTSD includes seven specific criteria, including duration of at least 1 month

● When obtaining the

history, patients with

and functional impairment, an initial traumatic event, intrusive reexperiencing,

possible posttraumatic avoidance, numbing or negative alterations in cognition and mood, and

stress disorder should be alterations in arousal and reactivity (SDC 11-1; links.lww.com/CONT/A252).

asked about reexperiencing When obtaining the history, clinicians should ask the patient about the

the trauma through

following symptoms: reexperiencing (the trauma) through associated thoughts,

associated thoughts,

physiologic response, physiologic response, flashbacks, or nightmares; avoidance of trauma reminders;

flashbacks, or nightmares; loss of enjoyment; negative feelings or thinking; a sense of blame and isolation;

avoidance of trauma hyperarousal; irritability; poor sleep; tension; hypervigilance; and reactivity (more

reminders; loss of

highly emotional, less control of anger, possible self-destructive or aggressive

enjoyment; negative

feelings or thinking, a sense behavior). Avoidance can exhibit as an inability to leave the house for fear of

of blame and isolation; another assault or accident, not speaking with friends in case they ask about the

hyperarousal; irritability; traumatic event, or not being able to watch TV in case there is a trigger such as a

poor sleep; tension; motor vehicle accident. Common physiologic responses to trauma reminders

hypervigilance; and

reactivity. include increased heart and respiratory rate, sweating, nausea, and flushing. Patients

may also have significant features of dissociation, including feeling like an outside

● The different phenotypes observer or feeling detachment from self (depersonalization), or experiencing a

of posttraumatic stress sense of unreality, distance, or distortion of the external world (derealization). The

disorder make it more

difficult to recognize, and

addition of the dissociation subtype in DSM-5 describes acute PTSD and allows

symptoms may be masked what was previously informally called complex PTSD, a phenotype of PTSD

by comorbid substance use, from childhood trauma, to be diagnosed using the same criteria (SDC 11-1;

brain injury, depression, or links.lww.com/CONT/A252).18

anxiety disorder.

A flashback (as compared to the experience of a normal memory) is an

● Two phenotypes of involuntary dissociative episode. The patient temporarily involuntarily

posttraumatic stress reexperiences an aspect of the past traumatic event as if it were happening in the

disorder have been present (eg, smelling or tasting blood after being shot in the jaw or feeling

described, dysphoria and breathless with pain in the sternum after a steering wheel/airbag/seat-belt injury

emotional numbing, both

with reexperiencing, from a multivehicle accident). Once initiated, a flashback often continues

avoidance, and intrusively, as if the play button has been pressed for a horror movie.19 This

hyperarousal but differing in experience is cognitively disorganizing, often terrifying, and highly distressing.

sleep, irritability, and The clinical assessment of PTSD includes identifying events as traumatic and

concentration symptoms.

eliciting their significance, identifying the individual’s risk factors, and detecting

the signs of failure of recovery from the trauma. The different phenotypes of

PTSD make it more difficult to recognize, and symptoms may be masked by

comorbid substance use, brain injury, depression, or anxiety disorder.

PHENOTYPES OF POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Two main phenotypes of PTSD have been described: dysphoria PTSD with

disrupted sleep and more dysphoric irritability, which often occurs after an acute

traumatic event as an adult (CASE 11-1), and complex PTSD from repeated

childhood trauma, often with an “emotionally numbed” presentation of PTSD

(CASE 11-2).21,22 Both phenotypes have reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal,

but they differ in sleep, irritability, and concentration symptoms (FIGURE 11-123).

QUESTIONNAIRES AND SCREENING TOOLS

A diagnosis of PTSD should not be made by self-report tools alone; clinical

assessment or clinician-administered semistructured interviews are needed to

confirm the diagnosis, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5

(SCID-5)24 and the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS).25 A 2005 review

876 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

A 22-year-old woman presented for a new episode of psychiatric CASE 11-1

assessment and care with severe depression and posttraumatic stress

disorder (PTSD). Two years earlier, while walking home after an evening

lecture, she was sexually assaulted by a stranger, who held a knife to her

throat. A passerby took her to a police station, and a rape procedure was

conducted. The woman was in a shocked state and felt emotionally

numb. The next day, she began to experience intense fear and startle

reactions to loud sounds. She was unable to watch the news on television

or walk outside unaccompanied without fear, even during the day. She

experienced severe insomnia, nightmares of the rape, and daily flashbacks.

She became suicidally depressed, despite seeing a psychiatrist for

supportive psychotherapy and receiving an antidepressant over a 2-year

period. She was hospitalized twice and received 12 courses of bilateral

electroconvulsive therapy but remained depressed, with profound PTSD.

The patient began trauma-focused therapy with the psychiatrist in this

new episode of care. She was provided with psychoeducation about

trauma, PTSD and avoidance, and the rationale for imaginal and behavioral

exposure to feared memories and situations. She was treated with sertraline

150 mg once daily and risperidone 1 mg at night. Prazosin was carefully

titrated up to 2 mg to treat nightmares.20

The patient wrote out the major “chapters” of the rape memory narrative

to address them, with gradually increasing exposure to distressing details of

the rape both in her journal as well as in sessions. She was asked to recall

the experience as if it were happening in 90-minute taped imaginal exposure

sessions, in which she was asked to recount the trauma in sequence from

start to finish in as much detail as possible, in the present tense, while the

therapist aimed to keep her engaged within a moderate range of anxiety and

distress. This exposure therapy helped her to form a narrative and process

thoughts and emotions surrounding the event. She listened to the tapes

daily between sessions and recorded her subjective units of distress. In

parallel, she listed the things she avoided and began to deliberately expose

herself to these (objectively safe) situations, first accompanied, then alone.

After 6 months, the patient’s overt PTSD symptoms went into remission,

except for brief periods of high stress, and after 1 year, the prazosin was

discontinued. The patient was able to speak about the rape and reestablish

intimate relationships in her social and interpersonal life, but she was unable

to reestablish her chosen career track.

This case exemplifies the dysphoric, fear-based, hyperaroused adult after COMMENT

a single traumatic event, who also developed a severe depression

comorbid with the PTSD. Left untreated, most people with severe PTSD

will develop another psychiatric disorder. Like this woman, these patients

will mostly not recover until their PTSD is recognized and treated by

someone with PTSD expertise.

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 877

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

CASE 11-2 A 24-year-old man from Bosnia was referred for psychiatric assessment

while undergoing treatment for sarcoma, as he was missing oncology

appointments and had difficulty coping with his treatment because of

extreme anxiety and difficulty surrounding treatment decisions and side

effects. His childhood experience included an absent father, a mother

with an alcohol use disorder, and little routine. At age 12, he witnessed his

mother, two siblings, and others being killed outside their family home,

while he managed to keep hidden. He spontaneously recounted this story

during the consultation with a flat, disengaged affect.

His main symptoms were flat mood (with a loss of meaning in life and

little joy or positive emotion but no feelings of guilt or worthlessness),

decreased energy, and sense of hopelessness. He reported feeling

numb, shut down, and internally dysphoric. He did not startle easily and

reported good sleep but did not wake refreshed. He was not especially

irritable. He experienced flashbacks and nightmares, and he avoided

Bosnians and reminders of genocide. He did not seek psychiatric help

after he immigrated, because he could not bear to “open up” the

memories. He did not have hypervigilance but was disoriented and dazed

during flashbacks and for some of the day, especially after his cancer

diagnosis. Overall, his flat, dysphoric state could have been mistaken for

a sole diagnosis of depression but without a feeling of heaviness or guilt

to account for his lack of functioning. However, this was a shut-down,

flat, numbed presentation of comorbid depression and complex

posttraumatic stress disorder; he was difficult to access/engage,

preoccupied, and slow, with derealization.

Venlafaxine XR was begun and titrated up to 150 mg, and he was given

support with the logistics of making appointments and treatment

decisions. He was referred to a local specialized center for victims of

torture for trauma-focused therapy, processing, and eye movement

desensitization and reprocessing therapy to help with recovery from his

childhood trauma. He was seen for existential concerns at the cancer

center; he struggled to accept that something else had gone wrong in his

life, as if he were cursed. He completed treatment and eventually

returned to school. One year later, he was noted to be more animated and

engaged in conversation, able to withstand direct gaze, and present in the

moment. He said he felt better than he ever remembered feeling in his life.

COMMENT This case exemplifies the difficulty of adapting to new trauma in those with

complex posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or childhood trauma. It also

demonstrates how easy it can be to misdiagnose PTSD as depression in this

type of shut-down, numbed presentation. All patients with significant

complex trauma will be at risk of an increase in symptoms or new

symptoms of PTSD when faced with serious medical illness or acute

physical trauma.

878 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

concluded that the mean KEY POINTS

diagnostic efficiency of screening

● Patients having four or

tools was over 85% and that more categories of

using a small number of core childhood trauma had a 4 to

symptoms of PTSD was effective 12 times greater increased

across trauma populations.26 risk for substance abuse,

depression, and suicide

Four validated self-report scales

attempts; a 2 to 4 times

are commonly used: the Impact greater risk of smoking, 50

of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R),27 or more sexual partners, and

the PTSD Checklist–Civilian sexually transmitted

disease; and a 1.4 to 1.6 times

Version (PCL-C),28 the PTSD

greater risk of physical

Symptom Scale-Self-Report inactivity and morbid

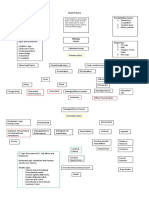

Version (PSS-SR),29 and the FIGURE 11-1 obesity.

Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS).30 Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and

complex PTSD in classification hierarchy. This ● Of deployed US military

figure demonstrates the underlying similarity in personnel, 14% to 16% were

IMPACT ON LONG-TERM found to have posttraumatic

symptom clusters in both PTSD and complex

PHYSICAL AND PTSD. Since complex PTSD usually results from stress disorder, which was

MENTAL HEALTH repeated trauma in childhood, thus impacting prospectively associated

The physical and mental health development, personality traits often include with early-age heart disease

difficulties with sense of self/self-esteem mortality among those free

correlates of a lifetime trauma of heart disease at baseline.

(self-organization), intense uncontrolled

load are consistent with an emotions (affect dysregulation), and trust of

epigenetic understanding of the others, as well as attachment difficulties

etiology and comorbidity of (leading to difficulties in relationships).

PTSD.31–33 One mechanism Consequently, both groups need treatment for

PTSD. In addition, patients with complex PTSD

involves repeated states of require longer-term attachment-informed

physiologic stress response and psychological work to change the way they cope

loss of regulation, with increased and experience the world and themselves.

Modified from Cloitre M, et al, Eur J Psychotraumatol.23

risk of psychiatric and physical © 2013 The Authors.

disorders. In a landmark paper,

Felitti and colleagues34 reported a

strong relationship between abuse

or childhood family dysfunction and increased adult health risk behaviors and

mortality, including mortality from cancer and heart, liver, lung, and skeletal

disease. Patients having four or more categories of childhood trauma had

a 4 to 12 times greater risk for substance abuse, depression, and suicide

attempts; a 2 to 4 times greater risk for smoking, 50 or more sexual partners,

and sexually transmitted disease; and a 1.4 to 1.6 times greater risk of

physical inactivity and morbid obesity compared to patients with no

childhood trauma.34

Literature examining the mental and behavioral health in armed forces deployed

in Iraq and Afghanistan suggests that depression is more common in women and

substance use is more common among men.35 Of deployed US military personnel,

14% to 16% were found to have PTSD, which was prospectively associated with

early-age heart disease mortality among those free of heart disease at baseline.36

This finding suggests that early-age heart disease may be an outcome after

military service in veterans with PTSD.37

PTSD is associated with smoking, drug and alcohol abuse, and obesity in

military veterans and civilian trauma survivors.38 This may be due to maladaptive

coping with distress with habitual use of substance or food. Alcohol and nicotine

use is high in PTSD; the odds of alcohol use disorders increase with the number

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 879

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

of PTSD criteria the patient meets. Research on comorbid PTSD and substance use

disorder supports parallel treatment to reduce PTSD severity and drug/alcohol

use posttreatment and improve subsequent follow-up.39

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER AND NEUROLOGIC DISORDERS

Stroke-related PTSD is common, with 25% of patients developing PTSD in the

first year after stroke and over 10% having chronic PTSD 1 year later,40 which

can be an important factor in secondary prevention with medication adherence.

Patients with respiratory failure due to Guillain-Barré syndrome should also be

screened for PTSD afterward.41 In one study, 5.17% (12) of 232 patients with

multiple sclerosis developed PTSD.42

It used to be assumed that people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) had

decreased risk for PTSD, as they could not remember the trauma,43 and

TBI-related amnesia may be confused with traumatic dissociative amnesia, which

results in the patient being unable to recall some parts of the trauma without

evidence of a significant TBI. However, mild TBI confers extra risk of PTSD, and

the combination is synergistic, with increased symptoms, cognitive impairment,

and difficulty in treatment.44

Migraine may predispose patients to PTSD and headache-related disability,14

especially in male patients.45,46

DEVELOPMENT OF POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Learning and evolutionary theory add to our theoretical understanding of two main

experiences of PTSD: (1) extreme distress when faced with any trauma-associated

cues due to fear conditioning (the learned association of all trauma-related

experience to fear/distress, such as an assault by a tall bald man may generalize

to fear of all tall or all bald men, as tallness or baldness becomes associated

with fear) and (2) avoidance

behavior, which is reinforced by

immediate relief when a trauma

cue is removed or avoided (this is

called negative reinforcement, as it

is relief on removal of aversive

cue).47 During exposure therapy,

the patient is guided to engage

with a fear memory repeatedly

while feeling safe in the here and

now (in the therapist’s office)

and to discuss and process the

thoughts and emotions of this

“silent horror movie” memory

FIGURE 11-2 cognitively with the therapist,

Fear consolidation. Individuals with posttraumatic thus disrupting and altering the

stress disorder show increased sensitization to memory by extinguishing fear

stress, overgeneralization of fear, and impaired

extinction of fear memories. Individuals who recover

and enabling a different way of

from stress appropriately demonstrate an ability thinking about it. This is

to discriminate between fear-inducing and normal followed by reconsolidation of

stimuli as well as normal extinction of fear the less distressing, more

memories.

Reprinted with permission from Mahan AL, Ressler KJ,

processed memory

Trends in Neurosciences.48 © 2012 The Authors. (FIGURE 11-248).

880 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Understanding Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Using Cognitive and KEY POINTS

Learning Theory

● Mild traumatic brain injury

Classic fear conditioning involves the pairing of an innate fear reaction confers extra risk of

(adrenergic response: startle, increased heart rate) to an unconditioned stimulus posttraumatic stress

(eg, stabbing) with a previously neutral valence (conditioned) stimulus (eg, disorder, and the

sound of ambulance, sight of blood). If PTSD ensues, the sound of a siren or the combination is synergistic,

with evidence of increased

sight of spilled ketchup may induce a fear response and flashbacks. Avoidance

symptoms, cognitive

symptoms are negatively reinforced by operant conditioning, as avoidance of impairment, and difficulty

triggers reduces distress and leads to reinforced learning that avoidance is the in treatment.

best action. Failure to recover from a trauma results in continued maladaptive

avoidance, repeatedly reinforced. ● Learning theory, along

with memory engagement,

disruption, alteration, and

Neurobiology, Neuroendocrinology, and Neurocircuitry reconsolidation, underpins

Animal models of PTSD have elucidated neurobiological underpinnings in the use of prolonged

humans. PTSD-like effects have been induced in rats, with anxiety behaviors of exposure therapy for

posttraumatic stress

avoidance, reduced concentration and sleep, decreased hippocampal volume, disorder.

physiologic changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and

amygdala hyperactivity.49 Traumatic events interfere with the memory function ● Animal models of

of the hippocampus and increase the plasticity processes in the amygdala.50 posttraumatic stress

disorder have elucidated

Physiologic changes have been reproduced, including decreased growth rate and

neurobiological

thymus weight and increased adrenal weight, anxiety and startle response, underpinnings in humans.

cardiovascular reactivity, and hormonal reactivity, while fear stimuli result in

freezing and avoidance. Zoladz and colleagues49 also found that predator ● Three main brain

exposure alone did not cause persistent PTSD-like behavior, so a social instability structures involved in

appraising threat and

model was introduced by randomly changing the rat roommate combinations, regulating fear have been

which successfully produced PTSD-like symptoms with predator exposure, studied in posttraumatic

replicating findings in humans that insufficient social support and instability are stress disorder: the

associated with increased risk of PTSD. prefrontal cortex, the

hippocampus, and

Neurobiological correlates support the learning hypothesis of PTSD and explain the amygdala.

its symptoms. Three main brain structures involved in appraising threat and

regulating fear have been studied in PTSD: the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, ● In posttraumatic stress

and the amygdala.51 disorder, the amygdala is

mostly hyperactive,

The amygdala plays a pivotal role in the brain circuit regulating fear

promoting an abnormal fear

conditioning.52 The central amygdala is responsible for sending fear signals to response of hypervigilant

the hypothalamus and brainstem. The medial prefrontal cortex is able to inhibit and hyperaroused behavior.

the amygdala in a top-down manner and reduces subjective distress. The

hippocampus codes fear memories and appraises and interprets the context and

threat of memories evoked. Together with the medial prefrontal cortex, the

hippocampus modulates fear, regulating the amygdala’s output to subcortical

brain regions that activate the fear response.

In PTSD, the amygdala is mostly hyperactive, promoting an abnormal fear

response of hypervigilant and hyperaroused behavior.53 PTSD results from an

acquired impaired capacity for fear extinction, possibly mediated by less activity

in the medial prefrontal cortex. Stress causes limbic activation, which inhibits

prefrontal cortex functioning, reducing inhibition of the amygdala and resulting in a

further fear response (FIGURE 11-3).

Neuroanatomic changes have been found in PTSD, including a decreased volume

of the prefrontal cortex, with decreased activation on exposure to traumatic

events.54 This loss of cortical reappraisal and ability to reduce the heightened

amygdala response allows repeated activation of the amygdala and dysregulated

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 881

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

FIGURE 11-3

Limbic system of the brain and its involvement in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The

prefrontal cortex is responsible for reactivating past emotional association and emotional

regulation. The hippocampus allows for conditioned fear of traumatic events and learned

responses to contextual cues. Both the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex have altered

responsiveness in patients with PTSD. The top-down control of the amygdala by the

hippocampus and prefrontal cortex could play a role in the hyperactivity of the amygdala

seen in patients with PTSD who are hypervigilant. The ultimate effects of PTSD include

increased stress reactivity, generalized fear responses, and impaired extinction. Other

affected regions of the brain include the anterior cingulate cortex, the orbitofrontal

cortex, the parahippocampal gyrus, the thalamus, and the sensorimotor cortex, which

contributes to fear regulation and PTSD.

Reprinted with permission from Mahan AL, Ressler KJ, Trends in Neurosciences.48 © 2012 The Authors.

circuits between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system. Reconsolidation of

unstable fear memories can lead to ongoing distressing flashbacks that feed into

further activation of the amygdala, with reduced prefrontal cortex inhibition. This

leads to the trauma memories becoming more intrusive over time, with persistent

hyperarousal and distress. Unstable trauma memories also provide an opportunity

for exposure therapy and thus extinction of fear from the memory before

reconsolidation of a more stable and less fear-linked memory.

Reduced prefrontal cortex function may also explain the impaired executive

function seen in PTSD as well as cognitive deficits due to decreased volume and

dysfunction in the hippocampus, with specific deficits in hippocampal-dependent

learning and memory.55 PTSD leads to changes in the HPA axis stress response

(with possible epigenetic changes) and the sympathetic nervous system, with

increased arousal, skin conductance, adrenaline and noradrenaline levels, blood

pressure, and anxiety behavior (FIGURE 11-456).57

Lifetime trauma burden increases the risk for developing acute disabling

symptoms of PTSD in those who have experienced previous trauma or have

882 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

KEY POINTS

● Reconsolidation of

unstable fear memories can

lead to ongoing distressing

flashbacks that feed into

further activation of the

amygdala, with reduced

prefrontal cortex inhibition.

This leads to the trauma

memories becoming more

intrusive over time, with

persistent hyperarousal

and distress.

● Lifetime trauma burden

increases the risk for

developing acute disabling

symptoms of posttraumatic

stress disorder in those who

have experienced previous

trauma or have chronic

complex posttraumatic

stress disorder.

FIGURE 11-4

Stress response. Normal responses to stress (A), stress response in a patient with major

depressive disorder (B), and stress response in a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) (C). In each panel, arrow thickness denotes the magnitude of biological response.

In healthy subjects and those with depression, periods of stress are associated with

increased cortisol and corticotropin-releasing factor. Corticotropin-releasing factor acts

on the anterior pituitary to stimulate corticotropin, which, in turn, stimulates cortisol

production by the adrenal cortex. Cortisol inhibits the release of both corticotropin and

corticotropin-releasing factor while also inhibiting many other stress-related biological

reactions. In patients with PTSD, cortisol levels are low, which allows for increased levels

of corticotropin-releasing factors. Additionally, the negative-feedback system of the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is more sensitive in patients with PTSD, contributing to

altered stress regulation in PTSD.

Reprinted with permission from Yehuda R, N Engl J Med.56 © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society.

chronic complex PTSD. A longer and stronger physiologic reaction occurs

on anticipation or exposure to stress in those previously traumatized (due to the

initial increased secretion of cortisol and receptor density) compared to those

who have not experienced trauma, although enhanced negative feedback

follows, with an ongoing lower baseline cortisol.58 This phenomenon provides

the neurobiological explanation of why those with past trauma might be more

likely to develop PTSD with subsequent trauma.

Recent Trends in the Neurobiology of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

An important area of recent research in PTSD is the study of genetic and

epigenetic phenomena with increasing trauma load. Epigenetic alteration of

the BDNF gene has been linked with brain function, memory, stress, and

neuropsychological changes.59 Using the psychosocial predator stress model,

Zoladz and colleagues demonstrated hypermethylation of the BDNF gene in the

dorsal hippocampus in mice.49 Changes in brain structures and pathways have

been explored in those with childhood trauma.60

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 883

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Interventional research with the aim of regulating the HPA-prefrontal

cortex-amygdala circuitry includes electroconvulsive therapy, deep brain

stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic

stimulation (rTMS), and transcranial direct current stimulation.

Neurotransmitters involved in control of thinking (such as g-aminobutyric acid

[GABA]) could be a target of treatment for PTSD. The current understanding

of the neurobiology of PTSD may explain the efficacy of selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as a partial treatment for PTSD, as they increase

plasticity and learning capacity so that memories and danger assessment

of trauma-related cues can be altered more easily and sympathetic overdrive

is lessened.

TREATMENT OF POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

A broad, evidence-based approach is often needed in the treatment of PTSD,

including managing comorbid psychiatric illness, brain injury, and chronic pain;

medication; and using different therapeutic techniques, including prolonged

exposure therapy, cognitive processing therapy, and eye movement

desensitization and reprocessing therapy.

Early evidence supports new treatments for PTSD, such as rTMS, and

preliminary effectiveness has been shown for virtual reality exposure therapy,

Internet-based cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy,

brainspotting, and yoga.61,62

A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological treatments for

adults with PTSD demonstrated the efficacy of exposure therapy, including

prolonged exposure therapy, cognitive therapy, cognitive-behavioral

therapy mixed therapies, cognitive processing therapy, eye-movement

desensitization and reprocessing therapy, and narrative exposure therapy, in

improving PTSD symptoms.63 However, evidence is limited on whether any

one treatment or approach is more effective for particular symptoms or

patients. The tolerability and potential adverse effects of a particular

psychotherapy intervention over medication have also not yet been

fully explored.

In February 2017, the American Psychological Association published a

guideline for the treatment of PTSD in adults.64 The recommendations

were based on the strength of the evidence, outcomes, patient-reported

preference, balance of benefits, and applicability to the treatment population.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, cognitive therapy,

and prolonged exposure therapy received strong recommendations. Other

suggested treatments included brief eclectic psychotherapy, eye movement

desensitization and reprocessing therapy, and narrative exposure therapy.

Recommended medications included fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline,

and venlafaxine, while insufficient evidence was found for risperidone

and topiramate.

Prolonged exposure therapy uses learning theory to extinguish fear from the

trauma memory by repeatedly engaging in the memories in a safe environment

without a feared outcome.65 Grounding and distraction may be needed in a

patient who quickly dissociates (the patient is physically present in the room but

increasingly goes back to the traumatic event in his/her mind, to the extent of

smelling smoke, coughing, feeling hot and terrified, as if back in the fire). In

prolonged exposure therapy, the memory is associated with less and less fear

884 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

each time it is engaged, processed, and consolidated, gradually reversing the KEY POINTS

classic conditioned response. The patient listens to a tape of the session daily,

● The current

while also gradually reducing avoidance behavior (eg, leaving the house, walking understanding of the

down a street, crossing the street, being a passenger in a car, driving), which neurobiology of

reverses the operant negative reinforcement, and the patient’s world gradually posttraumatic stress

opens up again. disorder may explain the

efficacy of selective

Cognitive theory provides a model of PTSD as a failure to accept and integrate

serotonin reuptake

a trauma and explains symptoms of avoidance.66 Cognitive processing therapy inhibitors as a partial

addresses the distressing thoughts (eg, “it was my fault”) and associated feelings treatment for posttraumatic

(eg, guilt) that people may have in response to trauma.67 Self-blame and guilt stress disorder as they

increase plasticity and

will make patients avoid trauma-associated cues, and, depending on how they

learning capacity so that

think about the future, they may become extremely avoidant and limited in their memories and danger

daily life (eg, thinking that the world is a dangerous place and they cannot assessment of trauma-related

keep themselves safe). cues can be altered more

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy is a therapy easily and sympathetic

overdrive is lessened.

developed in 1987 for the treatment of PTSD.68,69 A good evidence base exists

for eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, although ● A broad, evidence-based

controversy exists over whether the mechanism of eye movement approach is often needed in

desensitization and reprocessing therapy is distinct from prolonged exposure the treatment of

posttraumatic stress

therapy and whether it offers a treatment that is any more effective. In eye disorder, including

movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, the patient is asked to allow managing comorbid

distressing trauma images to emerge while remaining aware of associated psychiatric illness, brain

thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations and using side-to-side eye movements injury, and chronic pain;

medication; and using

or bilateral stimulation such as hand tapping.68,69 This is thought to allow

different therapeutic

processing of the trauma memory. techniques, including

prolonged exposure

Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy therapy, cognitive

Brief eclectic psychotherapy combines and integrates elements from processing therapy and eye

psychodynamic therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and directive movement desensitization

and reprocessing therapy.

psychotherapy.70 Psychoeducation and exposure occur jointly with the patient

and therapist; a structured writing task and memorabilia are used to help ● The 2017 American

the patient access, feel, and express his or her trauma-related emotions. Psychological Association

This combination could be argued to effectively target social connection and guideline for the treatment

of posttraumatic stress

prefrontal cortex emotional regulation, correct cognitive distortions, and

disorder in adults gives

allow habituation. strong recommendation for

cognitive-behavioral

Recent Trends in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder therapy, cognitive

A recent consensus statement called for more research into novel pharmacologic processing therapy,

agents, therapeutic strategies, and targets based on our current understanding cognitive therapy, and

prolonged exposure

of PTSD neurocircuitry and mechanisms.71 Two reviews confirm new evidence

therapy.

for the use of rTMS based on interrupting the brain circuitry of PTSD (including

reducing hyperactivity of the amygdala), facilitating fear extinction capacity ● Prolonged exposure

and increasing cognitive control in the salience network (a network of brain therapy uses learning theory

regions of the brain that discriminate between stimuli, deciding how to allocate to extinguish fear from the

trauma memory by

attention to new stimuli and coordinating the brain's responses).72,73 Combining repeatedly engaging in the

brief script-driven exposure with deep transcranial magnetic stimulation was memories in a safe

found to reduce PTSD in patients who were treatment resistant.74 environment without a

feared outcome.

ONLINE THERAPY/VIRTUAL REALITY. In the past decade, e–mental health has been

shown to be a viable treatment for PTSD through virtual platforms in the form of

individual online psychotherapy, virtual reality programs, and Internet-based

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 885

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

self-help programs as the accessible first step of care.75 Internet-based

cognitive-behavioral therapy using video, audio, and virtual reality has

evidence as a preventive intervention early in the posttrauma period.76

TREATMENT OF COMPLEX TRAUMA

The picture and experience of complex trauma is different from acute

adult-onset PTSD after a single traumatic event. Some authors make the

argument that short-term, non–attachment-attuned treatment (treatment that is

not predicated on the therapeutic relationship being part of the treatment) for

single-trauma PTSD should not be assumed to be effective in those with complex

trauma.77,78 Little robust literature exists on effective treatment for complex

PTSD resulting from repeated trauma, including trauma in childhood. Some

Level 2 and Level 3 evidence exists for sensorimotor therapy and brainspotting

in the treatment of complex trauma. In brainspotting, the patient is guided

in a state of “focused activation” to correlate neurologic stimulation and

internal experience and allow for processing.61 It is posited that holding attention

on that “brainspot” allows processing of the traumatic event to continue

until activation has cleared. Significant controversy remains regarding the

mechanism of action of brainspotting, and strong evidence for its effectiveness

is lacking, partly because of the difficulty of manualizing this therapy into a

semistructured model of exact replicable steps.

PREVENTION OF AND EARLY INTERVENTION FOR POSTTRAUMATIC

STRESS DISORDER

Mitigation of the risk of PTSD pretrauma in the military and first responders is

gaining momentum, given concerns about the cost and disability associated with

PTSD. Interest is also growing in screening for PTSD in medical populations,

with evidence of improved clinical outcomes with secondary prevention and

early treatment.

Primary Prevention

Currently, a strong literature on successful primary prevention is lacking. Various

strategies have been used, such as pharmacologic intervention, pre–military

deployment screening for risk factors or stress, promotion of resilience, and

immediate postdeployment individual exposure therapy. Two recent studies

showed some promise for hydrocortisone in pretraumatic injury,79 and four

sessions of computerized attention bias modification training, thought to

disrupt threat monitoring and anticipatory stress response, reduced the risk

for PTSD.80

Secondary Prevention

Early posttrauma intervention, such as early brief exposure starting in the

emergency department to disrupt memory consolidation by habituating and

reducing the fear associated with the trauma memory, has had some success.81

Other early interventions to attempt to disrupt fear conditioning by reducing the

level of fear and arousal using propranolol or opioids have mixed evidence;

previous trials with clonidine and prazosin were not effective in reducing PTSD,

although prazosin has some evidence for reducing nightmares and improving

sleep in established PTSD (via a1 receptor antagonism).20

886 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Recent Trends in the Prevention of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder KEY POINTS

Interest in how PTSD impacts the brain in the neurobiology of childhood

● Cognitive processing

survivors of trauma and in understanding and preventing intergenerational therapy addresses the

transmission of trauma is growing. Intergenerational transmission of trauma distressing thoughts and

may involve epigenetic phenomena and can also be understood in terms of associated feelings that

attachment and the impact of unprocessed trauma on the parent’s capacity to people may have in

response to trauma.

nurture his or her children (as illustrated in the Still Face Experiment82).83

PTSD in medical populations is the subject of ongoing program development ● Emerging evidence exists

and research, including patients in the intensive care unit; patients with HIV, for the use of repetitive

cancer, or stroke; patients who have had cardiac surgery or an organ transplant; transcranial magnetic

or patients who have given birth. Identifying those at particular risk and screening stimulation for

posttraumatic stress

for symptoms allows for sustainable stepped care, timely interventions, and disorder based on

judicious use of limited resources.84 interrupting the brain

Screening and early intervention in medical populations is an area of current circuitry of posttraumatic

research. Zatzick and colleagues84 conducted a trial in 207 acute physical stress disorder (including

reducing hyperactivity of

trauma survivors, screening for PTSD symptoms and then randomly the amygdala), facilitating

assigning to a stepped-care combined intervention (psychopharmacology and fear extinction capacity, and

cognitive-behavioral therapy, n = 104) or control (usual care, n = 103). At increasing cognitive control

6, 9, and 12 months postinjury, intervention participants had significantly in the salience network.

reduced PTSD symptoms compared to controls; they also showed improved

● Internet-based

physical function 1 year after hospitalization. Similarly, a stepped-care cognitive-behavioral

cognitive-behavioral therapy model of intervention in those who have had therapy using video, audio,

myocardial infarctions was found to improve outcomes.85 and virtual reality has

evidence as a preventive

A 2017 review demonstrated evidence that trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral

intervention early in the

therapy and modified prolonged exposure therapy delivered within weeks posttrauma period.

for individuals showing signs of distress due to a potential traumatic event

are effective to treat acute stress and early PTSD symptoms as well as to prevent ● Early posttrauma

PTSD.86 Posttrauma escitalopram improved sleep quality and had a signal intervention, such as early

brief exposure starting in

for secondary prevention in a subgroup of participants, and peritrauma the emergency department

intranasal oxytocin showed reduced PTSD symptoms after 1 month in those to disrupt memory

with high PTSD symptoms at baseline.87,88 Early intervention using video consolidation by habituating

games in the emergency department showed some success. This distracted and reducing the fear

associated with the trauma

patients, reduced further distressing activation of the fear memory, and was memory, has had some

associated with physiologic calming before memory consolidation in the success.

immediate posttraumatic period. Some research supports the use of agents

such as D-cycloserine (partial agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate [NMDA] ● Interest in how

posttraumatic stress

receptor) to augment the effects of learning.89

disorder impacts the brain

in the neurobiology of

EXISTENTIAL DISTRESS IN TRAUMA AND POSTTRAUMATIC GROWTH childhood survivors of

Apart from biological factors (eg, family history, past personal history of trauma and in understanding

psychiatric illness, TBI), psychological factors (eg, early loss, past trauma, low and preventing

intergenerational

self-esteem), and social factors (eg, low social support, financial difficulty), transmission of trauma

existential factors (finding meaning in an altered existence/life posttrauma, is growing.

coping with a threat to survival) can also play a part in trauma recovery.

Existential distress may result from a sense of demoralization, the inability to

accept the trauma, uncertainty about safety, death anxiety, and lost faith, and

they can all interfere with recovery.

In contrast, posttraumatic growth describes a philosophical change in

worldview after trauma, including increased gratitude to be alive, a sense of

connection to others, greater sense of meaning, spiritual well-being, and a sense

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 887

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

KEY POINTS of clear priority, with constructs of openness, optimism, and social support.90 A

2015 meta-analysis suggested active psychological intervention facilitates

● Identifying those at

particular risk for

posttraumatic growth and can help people make the most of adversity.91

posttraumatic stress

disorder and screening for

symptoms allows for CONCLUSION

sustainable stepped care,

Untreated PTSD is associated with a sense of personal chaos and distress.

timely interventions, and

judicious use of limited Patients cannot live normal lives, fully connect in relationships, or function at

resources. work and are highly avoidant of internal or external trauma-related cues; their

lives become painfully restricted. Since PTSD can easily be misdiagnosed, a

● Posttraumatic growth clear understanding and knowledge of the different presentations of PTSD

describes a philosophical

change in worldview after and patterns of functional impairment are important to prevent and mitigate

trauma, including increased PTSD-associated distress, adverse health consequences, and comorbidity.

gratitude to be alive, a sense The downstream health costs, suffering, and disability associated with PTSD

of connection to others, make it imperative to continue to research feasible, acceptable, effective,

spiritual well-being, and a

sense of clear priority, with

efficient, and accessible treatments for PTSD from single events as well as

constructs of openness, repeated childhood trauma. Ideally, primary and secondary prevention will

optimism, and social reduce the incidence and severity of PTSD. A failure to address acute or

support. lifelong PTSD can lead to epigenetic and attachment-based intergenerational

transmission of trauma.

● Untreated posttraumatic

stress disorder is associated It is hoped that understanding the neurobiological correlates of PTSD

with a sense of personal (hyperaroused amygdala and fear network and inhibition of the prefrontal

chaos and distress. Patients cortex salience network, with consequent emotional dysregulation) will combat

cannot live normal lives,

vestiges of internalized stigma or doubt by the general public in the existence of

fully connect in

relationships, or function at PTSD. This may reduce the associated shame of trauma vulnerability and

work and are highly avoidant increase the recognition of PTSD as a war wound or civilian trauma-related

of internal or external disorder that requires specialized multimodal treatment.

trauma-related cues; their The link between the mind and the body is a hot topic in medicine; PTSD

lives become painfully

restricted. provides the ideal paradigm for biopsychosocial research in biomarkers,

pharmacologic interventions, rTMS, sensorimotor psychotherapy, and

● The downstream health existential and trauma-focused cognitive therapies.

costs, suffering, and

disability associated with

PTSD make it imperative to

continue to research ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

feasible, acceptable, The authors would like to thank Saurav Barua, MPH, for his assistance with

effective, efficient, and references and literature review; Andrew Irwin, BSc, for his assistance with the

accessible treatments for

figures; and Clare Pain, MD, and Anthony Feinstein, MD, for their expert advice

posttraumatic stress

disorder from single events and comments.

as well as repeated

childhood trauma.

REFERENCES

1 Stam R. PTSD and stress sensitisation: a tale of 3 Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al.

brain and body Part 1: human studies. Neurosci Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National

Biobehav Rev 2007;31(4):530–557. doi:10.1016/ Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;

j.neubiorev.2006.11.010. 52(12):1048–1060. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.

1995.03950240066012.

2 Gradus JL. Prevalence and prognosis of stress

disorders: a review of the epidemiologic 4 Burri A, Maercker A. Differences in prevalence

literature. Clin Epidemiol 2017;9:251–260. rates of PTSD in various European countries

doi:10.2147/CLEP.S106250. explained by war exposure, other trauma and

cultural value orientation. BMC Res Notes 2014;

7(1):407. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-407.

888 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

5 Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Koenen KC, McLaughlin KA. 18 Thompson-Hollands J, Jun JJ, Sloan DM. The

Epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: association between peritraumatic dissociation

prevalence, correlates and consequences. Curr and PTSD symptoms: the mediating role of

Opin Psychiatry 2015;28(4):307–311. doi:10.1097/ negative beliefs about the self. J Trauma Stress

YCO.0000000000000167. 2017;30(2):190–194. doi:10.1002/jts.22179.

6 Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, et al. 19 Brewin CR. Re-experiencing traumatic events in

National estimates of exposure to traumatic PTSD: new avenues in research on intrusive

events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and memories and flashbacks. Eur J Psychotraumatol

DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress 2013;26(5): 2015;6(1):27180. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.27180.

537–547. doi:10.1002/jts.21848.

20 George KC, Kebejian L, Ruth LJ, et al.

7 Spottswood M, Davydow DS, Huang H. The Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of

prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in prazosin versus placebo for the treatment of

primary care: a systematic review. Harv Rev nightmares and sleep disturbances in adults

Psychiatry 2017;25(4):159–169. doi:10.1097/ with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma

HRP.0000000000000136. Dissociation 2016;17(4):494–510. doi:10.1080/

15299732.2016.1141150.

8 Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al. The size

and burden of mental disorders and other 21 Elhai JD, Biehn TL, Armour C, et al. Evidence for a

disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. unique PTSD construct represented by PTSD’s

Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;21(9):655–679. D1-D3 symptoms. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25(3):

doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. 340–345. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.10.007.

9 Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, Demmer RT, et al. 22 Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, et al.

Potentially traumatic events and the risk of six Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and

physical health conditions in a population-based neurobiological evidence for a dissociative

sample. Depress Anxiety 2013;30(5):451–460. subtype. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167(6):640–647.

doi:10.1002/da.22090. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168.

10 Edmondson D, Kronish IM, Shaffer JA, et al. 23 Cloitre M, Garvert DW, Brewin CR, et al. Evidence

Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for coronary for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: a

heart disease: a meta-analytic review. Am Heart J latent profile analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2013;

2013;166(5):806–814. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.031. 15:4. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706.

11 Greenberg MS, Tanev K, Marin MF, Pitman RK. 24 First MB, Williams JB, Karg RS, Spitzer RL.

Stress, PTSD, and dementia. Alzheimers Dement Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—

2014;10(3):S155–S165. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.008. Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research

Version; SCID-5-RV). Arlington, VA: American

12 Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The

Psychiatric Association, 2015.

prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in

the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol 25 Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The

Psychiatry 2007;61(3):348–358. doi:10.1016/ development of a clinician-administered PTSD

j.biopsych.2006.03.040. scale. J Trauma Stress 1995;8(1):75–90.

doi:10.1002/jts.2490080106.

13 Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Schlesinger MR, et al.

Comorbidity of partial and subthreshold PTSD 26 Brewin CR. Systematic review of screening

among men and women with eating disorders in instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. J Trauma

the national comorbidity survey-replication Stress 2005;18(1):53–62. doi:10.1002/jts.20007.

study. Int J Eat Disord 2012;45(3):307–315.

27 Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of

doi:10.1002/eat.20965.

Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress.

14 Smitherman TA, Kolivas ED. Trauma exposure Psychosom Med 1979;41(3):209–218.

versus posttraumatic stress disorder: relative

28 Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE.

associations with migraine. Headache 2013;53(5):

Psychometric properties of the PTSD

775–786. doi:10.1111/head.12063.

Checklist—Civilian version. J Trauma Stress

15 Monson CM, Gradus JL, La Bash HAJ, et al. The 2003;16(5):495–502.

role of couples' interacting world assumptions

29 Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO.

and relationship adjustment in women's

Reliability and validity of a brief instrument

postdisaster PTSD symptoms. J Trauma Stress

for assessing posttraumatic stress disorder.

2009;22(4):276–281. doi:10.1002/jts.20432.

J Trauma Stress 1993;6(4):459–473. doi:10.1002/

16 Simon NM, Shear KM, Thompson EH, et al. The jts.2490060405.

prevalence and correlates of psychiatric

30 Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, et al.

comorbidity in individuals with complicated

Assessment of a new self-rating scale for

grief. Compr Psychiatry 2007;48(5):395–399.

post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med

doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.002.

1997;27(1):153–156.

17 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

31 Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of

statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed

life stress on depression: moderation by a

(DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric

polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003;

Association, 2013.

301(5631):386–389. doi:10.1126/science.

CONTINUUMJOURNAL.COM 889

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

32 Zhang TY, Labonté B, Wen XL, et al. Epigenetic 44 Zatzick DF, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al.

mechanisms for the early environmental Multisite investigation of traumatic brain injuries,

regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid posttraumatic stress disorder, and self-

receptor gene expression in rodents and reported health and cognitive impairments. Arch

humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38(1): Gen Psychiatry 2010;67(12):1291–1300. doi:10.1001/

111–123. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.149. archgenpsychiatry.2010.158.

33 Yehuda R, Daskalakis NP, Lehrner A, et al. 45 Peterlin BL, Gupta S, Ward TN, MacGregor A. Sex

Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on matters: evaluating sex and gender in migraine

epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid and headache research. Headache 2011;51(6):

receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. 839–842. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01900.x.

Am J Psychiatry 2014;171(8):872–880. doi:10.1176/

appi.ajp.2014.13121571. 46 Friedman LE, Aponte C, Hernandez RP, et al.

Migraine and the risk of post-traumatic stress

34 Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. disorder among a cohort of pregnant women.

Relationship of childhood abuse and household J Headache Pain 2017;18(1):67. doi:10.1186/

dysfunction to many of the leading causes of s10194-017-0775-5.

death in adults. The Adverse Childhood

Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998; 47 Blechert J, Michael T, Vriends N, et al. Fear

14(4):245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. conditioning in posttraumatic stress disorder:

evidence for delayed extinction of autonomic,

35 Ramchand R, Rudavsky R, Grant S, et al. experiential, and behavioural responses. Behav

Prevalence of, risk factors for, and Res Ther 2007;45(9):2019–2033. doi:10.1016/

consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder j.brat.2007.02.012.

and other mental health problems in military

populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. 48 Mahan AL, Ressler KJ. Fear conditioning, synaptic

Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015;17(5):37. doi:10.1007/ plasticity and the amygdala: implications for

s11920-015-0575-z. posttraumatic stress disorder. Trends Neurosci

2012;35(1):24–35. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.007.

36 Gates MA, Holowka DW, Vasterling JJ, Keane TM,

Marx BP, Rosen RC. Posttraumatic stress 49 Zoladz PR, Diamond DM. Psychosocial stress in

disorder in veterans and military personnel: rats: animal model of PTSD based on clinically

Epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. relevant risk factors. In: Martin CR, Preedy VR,

Psychol Serv 2012;9(4):361–382. Patel VB, eds. Comprehensive guide to post-

traumatic stress disorder. Cham, Switzerland:

37 Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and

Springer, 2015:1–17. link.springer.com/

mortality among U.S. Army veterans 30 years

referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-

after military service. Ann Epidemiol 2006;

08613-2_58-1. Published June 26, 2015. Accessed

16(4):248–256.

April 2, 2018.

38 Boscarino JA. A prospective study of PTSD and

50 Southwick SM, Vythilingam M, Charney DS.

early-age heart disease mortality among

The psychobiology of depression and resilience

Vietnam veterans: implications for surveillance

to stress: implications for prevention and

and prevention. Psychosom Medicine 2008;

treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:

70(6):668–676.

255–291. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.

39 Tipps ME, Raybuck JD, Lattal KM. Substance 102803.143948.

abuse, memory, and post-traumatic stress 51 Shin LM, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. Amygdala, medial

disorder. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2014;112:87–100. prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in

doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2013.12.002. PTSD. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1071(1):67–79.

40 Edmondson D, Richardson S, Fausett JK, et al. doi:10.1196/annals.1364.007.

Prevalence of PTSD in survivors of stroke and 52 Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and

transient ischemic attack: a meta-analytic anxiety. Annu Rev Neurosci 1992;15(1):353–375.

review. PLoS One 2013;8(6):e66435. doi:10.1371/ doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.002033.

journal.pone.0066435.

53 Koenigs M, Grafman J. Posttraumatic stress

41 Chemtob CM, Herriott MG. Post-traumatic disorder: the role of medial prefrontal cortex

stress disorder as a sequela of Guillain-Barre and amygdala. Neuroscientist 2009;15(5):

syndrome. J Trauma Stress 1994;7(4):705–711. 540–548. doi:10.1177/1073858409333072.

doi:10.1007/BF02103017.

54 Dahlgren MK, Laifer LM, VanElzakker MB, et al.

42 Ostacoli L, Carletto S, Borghi M, et al. Prevalence Diminished medial prefrontal cortex activation

and significant determinants of post-traumatic during the recollection of stressful events is an

stress disorder in a large sample of patients acquired characteristic of PTSD [published

with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Psychol Med online ahead of print September 12, 2017].

Settings 2013;20(2):240–246. doi:10.1007/ Psychol Med. doi:10.1017/S003329171700263X.

s10880-012-9323-2.

55 Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, et al.

43 Vanderploeg RD, Belanger HG, Curtiss G. Mild Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic

traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nature

disorder and their associations with health Neurosci 2002;5(11):1242–1247. doi:10.1038/nn958.

symptoms. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90(7):

1084–1093. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.023.

890 JUNE 2018

Copyright © American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

56 Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl 70 Gersons BP, Schnyder U. Learning from traumatic

J Med 2002;346(2):108–114. experiences with brief eclectic psychotherapy

for PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2013;4.

57 Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Vermetten E, et al.

doi:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.21369.

Cortisol response to a cognitive stress challenge

in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related 71 de Kloet CS, Vermetten E, Geuze E, et al.

to childhood abuse. Psychoneuroendocrinology Assessment of HPA-axis function in

2003;28(6):733–750. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(02) posttraumatic stress disorder: pharmacological

00067-7. and non-pharmacological challenge tests, a

review. J Psychiatr Res 2006;40(6):550–567.

58 Sriram K, Rodriguez-Fernandez M, Doyle III FJ.

doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.002.

Modeling cortisol dynamics in the

neuro-endocrine axis distinguishes normal, 72 Berlim MT, Van den Eynde F. Repetitive

depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder transcranial magnetic stimulation over the

(PTSD) in humans. PLoS Comput Biol 2012;8(2): dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for treating

e1002379. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002379. posttraumatic stress disorder: an exploratory

meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind

59 Kim TY, Kim SJ, Chung HG, et al. Epigenetic

and sham-controlled trials. Can J Psychiatry

alterations of the BDNF gene in combat-related

2014;59(9):487–496. doi:10.1177/

post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatr

070674371405900905.

Scand 2017;135(2):170–179. doi:10.1111/acps.12675.

73 Trevizol AP, Barros MD, Silva PO, et al.

60 McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. The impact of

Transcranial magnetic stimulation for

childhood maltreatment: a review of neurobiological

posttraumatic stress disorder: an updated

and genetic factors. Front Psychiatry 2011;2:48.

systematic review and meta-analysis. Trends

doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00048.

Psychiatry Psychother 2016;38(1):50–55. doi:

61 Grand D. Brainspotting. A new brain-based 10.1590/2237-6089-2015-0072.

psychotherapy approach. Trauma Gewalt

74 Isserles M, Shalev AY, Roth Y, et al.

2011;3:276–285.

Effectiveness of deep transcranial magnetic

62 Cullen M. Mindfulness-based interventions: an stimulation combined with a brief exposure

emerging phenomenon. Mindfulness 2011;2(3): procedure in post-traumatic stress disorder—a pilot

186–193. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0058-1. study. Brain Stimul 2013;6(3):377–383. doi:10.1016/j.

brs.2012.07.008.

63 Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, et al.

Psychological treatments for adults with 75 Maercker A, Hecker T, Heim E. Personalized

posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic Internet-based treatment services for

review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2016; posttraumatic stress disorder. Nervenarzt 2015;

43:128–141. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.10.003. 86(11):1333–1342. doi:10.1007/s00115-015-4332-7.

64 American Psychological Association Guideline 76 Freedman SA, Dayan E, Kimelman YB, et al. Early