Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Relationship Between Mode of Delivery and Sexual Health Outcomes After Childbirth

Uploaded by

sipen poltekkesbdgOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Relationship Between Mode of Delivery and Sexual Health Outcomes After Childbirth

Uploaded by

sipen poltekkesbdgCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/274725131

The Relationship Between Mode of Delivery and Sexual Health Outcomes after

Childbirth

Article in Journal of Sexual Medicine · April 2015

DOI: 10.1111/jsm.12883 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

27 352

5 authors, including:

Alexandre Faisal-Cury Paulo Rossi Menezes

University of São Paulo University of São Paulo

41 PUBLICATIONS 814 CITATIONS 320 PUBLICATIONS 10,222 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Julieta Quayle Simone Grilo Diniz

University of São Paulo University of São Paulo

48 PUBLICATIONS 118 CITATIONS 90 PUBLICATIONS 1,411 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Cost-effectiveness of a mobile technology intervention compared to enhanced usual treatment for depressive symptoms in chronic non-communicable diseases

patients in Brazil and Peru: LATIM-MH Randomized Control Trial View project

Gender and maternity care View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Julieta Quayle on 24 April 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

1

The Relationship Between Mode of Delivery and Sexual Health

Outcomes after Childbirth

Alexandre Faisal-Cury, MD, PhD,* Paulo Rossi Menezes, PhD,* Julieta Quayle, PhD,*

Alicia Matijasevich, MD, PhD,* and Simone Grilo Diniz, MD, PhD†

*Preventive Medicine Department, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; †Maternal and Child Health Department,

University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

DOI: 10.1111/jsm.12883

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Several factors are implicated in the women’s sexuality after childbirth. Nevertheless, there is con-

flicting evidence about the influence of mode of delivery (MD)

Aim: To prospectively evaluate the relationship between MD and sexual health outcomes after childbirth

Methods: A prospective cohort study conducted between May 2005 and March 2007 included 831 pregnant women

recruited from primary care clinics of the public sector in São Paulo, Brazil. The exposure variable was MD:

uncomplicated vaginal delivery (spontaneous vaginal delivery without episiotomy or any kind of perineal laceration);

complicated vaginal delivery (either forceps or normal, with episiotomy or any kind of perineal laceration) and

cesarean delivery. Socio-demographic and obstetric data were obtained through a questionnaire applied during the

antenatal and postnatal period. Crude and adjusted risk ratios, with 95% confidence intervals, were calculated using

Poisson regression to examine the associations between MD and sexual health outcomes.

Main Outcome Measures: The three main sexual health outcomes were later resumption of sexual life, self-

perception of decline of sexual life (DSL), and presence of sexual desire.

Results: One hundred and forty-one women (21.9%) resumed sexual life 3 or more months after delivery. Although

87.1% of women had desire, DSL occurred in 21.1% of the cohort. No associations were found between MD and

sexual health outcomes.

Conclusions: Women’s sexuality after childbirth were not influenced by the type of delivery. Efforts to improve the

treatment of sexual problems after childbirth should focus beyond MD. Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR, Quayle J,

Matijasevich A, and Diniz SG. The relationship between mode of delivery and sexual health outcomes after

childbirth. J Sex Med **;**:**–**.

Key Words. Mode of Delivery; Sexual Functioning; Childbirth; Postpartum Depression

Introduction marital conflicts, depression, and economic strains

[4]. There is conflicting evidence about the role of

C hildbirth and the postpartum period repre-

sent a major life transition and usually has a

substantial impact on the sexual adjustment for

mode of delivery (MD) on sexual health outcomes.

In a retrospective cohort study of 626 pregnant

women over a 6-month period after childbirth,

both mothers and fathers [1] [2]. Not all women Signorello et al. [5] found that women who deliv-

adapt well to the psychological and biological ered with an intact perineum were significantly

changes, and two-thirds experience significant more likely to report better sexual outcomes. Klein

worsening in sexual functioning 6 months after et al. [6] found that women without perineal

childbirth [3]. A variety of reasons has been impli- trauma had a greater chance of resuming sexual

cated for the deterioration of sexual life including intercourse by 6 weeks postpartum in comparison

© 2015 International Society for Sexual Medicine J Sex Med **;**:**–**

2 Faisal-Cury et al.

with women with perineal trauma. A recent study tially better or worse sexual outcomes for women 2

of 1,507 nulliparous women found that most years after the birth compared with planned

women having a first birth did not resume vaginal vaginal delivery [23]. Another study with 276 iden-

sex until later than 6 weeks postpartum. Moreover, tical twin pairs demonstrated that childbirth was

women who had an operative vaginal birth, caesar- associated with decreased sexual function among

ean section, or perineal tear or episiotomy appear parous twins. However, MD was not found to be

to delay longer to resume sexual life [7]. In con- associated with altered sexual function in the 29

trast, studies about resumption of sexual life, per- pairs discordant for MD. The authors stated that

formed at 7 and 12 weeks after delivery, found that childbirth appears to have a lasting impact on

sexual activity was not influenced by the degree of sexual function, due to psychological more than

perineal laceration [8,9]. physical factors, well beyond the postpartum

Possible reasons for the association between period [24].

later resumption of sexual life and perineal trauma The purpose of the present study is to evaluate

include pudendal neuropathy, perineal pain and/or prospectively, up to 18 months after delivery, the

dyspareunia, and poor maternal health [10]. association between MD and sexual health out-

Pudendal nerve trauma has been demonstrated comes after childbirth, namely later resumption

after vaginal delivery [11,12]. Dyspareunia is of sexual life, presence of sexual desire, and self-

reported by 41–67% of women 2–3 months after report of sexual life decline.

childbirth [3,5,13,14]. Perineal pain typically

resolves by 3 months after delivery, although dys- Methods

pareunia takes somewhat longer to resolve [13].

Finally, poor health outcomes may impact sexual Study Design and Sample

function among women with severe obstetrical This was a prospective cohort study, conducted

morbidity [15]. Nevertheless, there is scarce as between May 2005 and March 2007, with 831

well conflicting evidence regarding the effect of pregnant women recruited from primary care

MD on sexual function in the period beyond the clinics of the public sector in three administrative

first year [16]. districts in the Western area of the city of São

In a longitudinal cohort study, Ejegård et al. Paulo, Brazil. The study area comprised a hetero-

evaluated the long-term sexual effects of episi- geneous population of approximately 400,000,

otomy and perineal laceration [17]. They stated where people with high, medium, and low income

that episiotomy may affect women’s sexual life live near each other. Private health care is usually

during the second year postpartum with more only accessible for women from the middle and

frequent pain and vaginal dryness at intercourse. upper middle classes. The public primary care

Moreover, other obstetrical factors and pain clinics offer free antenatal care for all women

history may also influence the propensity for dys- living in their catchment areas. Antenatal care is

pareunia. Van Brummen et al. in a prospective offered regularly, typically once a month, generally

cohort study with 377 nulliparous women evalu- starting as soon as the woman seeks a pregnancy

ated the factors that determine sexual activity and test at one of these clinics. Women followed in

satisfaction with the sexual relationship 1 year after these clinics are at low obstetrical risk. High-risk

the first delivery. They found that women were pregnancies are referred to regional hospitals

five times less likely to be sexually active after a for prenatal care. There were two public hospitals

third/fourth degree anal sphincter tear as com- in the study area, providing approximately

pared with women with an intact perineum [18]. 2,000 deliveries per year. After childbirth, the

On the other hand, studies report that sexual primary care clinics continue to provide clinical

dysfunction occurs postnatally but performance and gynecological care including contraception,

returns to prepregnancy levels within 1 year after breastfeeding orientation, and cervical smear.

delivery [19]. There is inconsistent evidence of Pregnant women between 20 and 30 weeks of

chronic dyspareunia after severe lacerations or pregnancy, whose conception occurred naturally,

operative delivery. Most studies suggest no differ- aged 16 years or older and with singleton pregnan-

ence after the first 6 [20], 12 [21], or even 36 cies, who were receiving antenatal care in primary

months [22]. Similar conclusion has been reached care clinics in the study area, were considered eli-

in relation to the long-lasting effects of cesarean gible for this study. Pregnant women with a history

delivery on sexuality. In the Breech Trial, planned of psychosis were excluded. Postpartum women

cesarean section was not associated with substan- were interviewed at home (mean time of interview

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

Mode of Delivery and Sexuality after Childbirth 3

after delivery: 11.1 months, standard deviation 60–113, and 114–810 USD). Household assets

[SD]: 2.3 months, range 6–18 months). Further measured included electricity, plumbing, com-

details of the study sample have been described puter, television, cable television, bathroom,

elsewhere [25]. telephone, and refrigerator. An “asset-based score

(AS)” was created using principal component

Instruments analysis. The primary component was used to gen-

Main Exposure Variable erate tertiles. Monthly family income per capita

Main exposure variable was mode of delivery. Data was defined as the monthly family income divided

on method of birth and degree of perineal trauma by the number of adults and children living in

were combined to provide a single variable. Three the house. Number of previous pregnancies was

categories were used: uncomplicated spontaneous recorded. Current obstetric data included gesta-

vaginal delivery (UVD) (without episiotomy or tional age, birth weight, and Apgar score at 5

any kind of perineal laceration); complicated minutes of life. Obstetric complications in the last

vaginal delivery (CVD) (either forceps or normal, pregnancy (yes/no) was defined by the presence of

with episiotomy or any kind of perineal lacera- a gestational age less than 37 weeks, a newborn

tion); and cesarean delivery (CD). Data about type weight under 2,500 grams, or a 5-minute Apgar

of delivery were extracted from medical charts. score less than 7. In the postpartum period,

breastfeeding was evaluated and defined as feeding

Main Outcome Variable the baby with breast milk, regardless of supple-

Two sexual health outcomes were evaluated by menting with other food. Breastfeeding length

direct questions. Time of resumption of sexual was ascertained through a single question to the

activity was ascertained through a single question mother: “How long have you breastfed?”. A vari-

to the mother (“Have you resumed your sexual life able (yes–no) for “breastfeeding more than 4

(intercourse) after childbirth?”). If the answer was months” was created. The presence of antenatal

yes, they were asked how many months after deliv- and postnatal depression was assessed with the

ery this happened. According to the answers given Self-Report Questionnaire (SRQ-20), which was

by women who restarted sexual life after child- developed for screening common mental disorders

birth, two groups were formed: earlier resumption in patients treated in primary care settings [26].

(1–2 months after delivery) and later resumption The SRQ-20 was validated in primary care

(3 or more months after delivery). Self-evaluation centers in Brazil, with 85% sensitivity and 80%

of sexual life was ascertained through questions to specificity [27]. The SRQ-20 has good psychomet-

the mother. One question was about the presence ric properties for diagnosing antenatal and postna-

of desire (“At the moment, do you feel desire tal depression, performing even better than others

to have a sexual life?”). The other question was instruments specifically designed for this purpose

about decline of sexual life (DSL) after childbirth [28]. The optimal cut-off point for the SRQ-20

(“Considering your sexual life before pregnancy, was set at 7/8 for the present study. Body mass

how would you describe your present sexual life: index (BMI) was assessed after delivery, and par-

improved, the same, worsened?”). The question ticipants were classified in three groups: under-

focused on the sexuality with a partner. According weight (below 19.9), normal weight (20–25.0), and

to the answers, two groups were formed: women overweight or obese (above 25.0). The presence of

who answered “improved” or “the same” were a health problem after childbirth was defined as

classified as “no decline” in sexual life; and women any consultation with a physician that has led to

who answered “worsened” were classified as any kind of surgery or hospitalization for treat-

“decline” in sexual life. ment. Timing of interviews was divided in three

groups: group 1: up to 8 months (99 participants;

Questionnaire 14.1%); group 2: from 9 to 12 months (408 par-

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics ticipants; 58.3%), and group 3: from 13 to 18

as well as obstetric information were obtained months (193 participants; 27.6%).

through a structured detailed questionnaire that

was applied during the antenatal assessment. Procedures

The information obtained included age, years of During the study period, trained research assis-

schooling, marital status, and skin color. Socioeco- tants went to the primary care clinics and

nomic indicators were “assets score” (in tertiles) approached all pregnant women. Eligible women

and “monthly family income per capita” (0–59, were invited to participate. Those who agreed

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

4 Faisal-Cury et al.

signed an informed consent form and were inter- eries (3.9%) were common reasons for performing

viewed between 20 and 30 weeks of pregnancy. a primary cesarean delivery. Women who had

The same group of research assistants interviewed resumed sexual activity were of similar age but

these women at home after childbirth. Participants were more educated, had higher family income,

then answered the SRQ-20 and the questionnaire and had less symptoms of depression and anxiety

with questions about sexual patterns and health than the group of 184 women who did not return

conditions. The Ethics Committee of the Univer- after delivery or did not resume sexual activity in

sity of São Paulo, School of Medicine, approved the postpartum period.

the research project. One hundred and forty-one women (21.9%)

resumed sexual life 3 or more months after deliv-

Statistical Analysis ery. The mean time for the beginning of sexual

The proportion of women reporting a decline in activity in the postpartum period was 2.1 months

sexual life, presence of sexual desire, and later (range 1–12). Although the majority of women

resumption of sexual life after childbirth was (87.1%) answered they had sexual desire, 136

calculated. Crude and adjusted risk ratios (RRs) women (21.1%) were classified as having a decline

with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were in sexual life after childbirth.

estimated using Poisson regression with robust In the bivariate analysis, MD was not associated

variance to examine the associations between with any sexual health outcomes (Table 1).

later sexual resumption, sexual desire, and decline Married women restarted sexual life after delivery

in sexual life after childbirth with MD. In the later than not married (single) women. In regard to

adjusted analyses, we examined the effects of MD the other sexual health outcomes, DSL was asso-

on these three sexual health outcomes accounting ciated with unmarried status, older women’s age,

for potential confounders. To be included as antenatal depression, postnatal depression, and

potential confounders, variables had to be associ- health problems whereas the presence of sexual

ated with MD and outcomes with a P level of <0.2. desire was associated with higher asset-based

Statistical associations were assessed with Wald score, higher familiar per capita monthly income,

tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered statisti- more than 9 years of education, white skin color,

cally significant. Statistical analyses were per- unmarried status, first pregnancy, antenatal and

formed using STATA version 12 (StataCorp, postnatal depression (Table 1).

College Station, TX, USA). After adjustment for potential confounders the

lack of association between MD and later resump-

tion of sexual life, DSL and sexual desire remained

Results

unchanged (Table 2).

Eight hundred and sixty-eight eligible pregnant

women were identified, and 831 (95.7%) women

Discussion

were included in the study during the antenatal

care period. Of these, 701 (84.4%) women were Our prospective cohort study showed that MD is

re-assessed during the postnatal period. Among not associated with different sexual health out-

701 postpartum women, 644 (91.8%) had resumed comes, including later resumption of sexual life,

sexual activity in the postpartum period and were desire, and self-perception of sexual life decline

included in this study. Participants had a mean age after childbirth. Although one in five women com-

of 25 years (range 16–44) and most were living plained of deterioration in sexual life after preg-

with a partner (78.1%). In addition, 46.5% had nancy, there is no relationship between MD and

completed 9 years of education. Regarding to the this type of sexual problem. Moreover, sexual

family income, 30.6% had a family per capita desire and later resumption of sexual life after

monthly income below US$ 60.00. According delivery were not associated with MD.

to the MD, 333 (51.7%), 105 (16.3%), and 206 In agreement with our results, a review of

(31.9%) were UVD, CVD, and CD, respectively. studies about sexuality during pregnancy and post-

Among the reasons for performing a cesarean partum confirmed that intercourse is resumed, on

section were intrapartum bleeding (3.5%); acute average, 6–8 weeks after birth in Europe and the

fetal distress (10.2%); one previous cesarean deliv- United States. Before the sixth week postpartum,

ery (10.6%); blood pressure disturbances (19.6%); only 9–17% of the couples practice intercourse,

and meconium stain (21.2%). Breech presentation in the sixth week 50–62%, in the second month

(3.9%) and two or more previous cesarean deliv- 66–94%, in the third month 88–95%, in the

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

Mode of Delivery and Sexuality after Childbirth 5

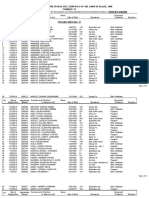

Table 1 Socioeconomic, demographic, and other health-related characteristics of the sample, according to the sexual

health outcomes

Later sexual Decline of Presence of

resumption sexual life sexual desire

N N (%) P level N (%) P level N (%) P level

Mode of delivery 0.85 0.09 0.07

UVD 333 73 (22.0) 76 (22.9) 282 (84.9)

CVD 105 25 (23.6) 14 (13.2) 99 (93.4)

CD 206 43 (20.8) 46 (22.3) 180 (87.4)

Asset score (tertiles) 0.67 0.08 0.008

First 204 49 (24.0) 52 (25.5) 167 (81.8)

Second 256 54 (21.1) 54 (21.1) 224 (87.5)

Third 184 38 (20.6) 30 (16.3) 170 (92.4)

Family per capita monthly income (USD) 0.87 0.87 0.002

0–59 195 44 (22.5) 42 (21.5) 156 (80.0)

60–113 218 48 (22.0) 46 (21.1) 196 (89.9)

114–810 224 46 (20.5) 44 (19.6) 205 (90.6)

Years of education (y) 0.35 0.08 0.001

1–4 108 23 (21.3) 31 (28.7) 85 (78.7)

5–9 192 49 (25.5) 39 (20.3) 162 (84.4)

>9 342 69 (20.2) 64 (18.7) 313 (91.5)

Skin color 0.38 0.96 0.03

White 304 62 (20.4) 64 (21.0) 274 (90.1)

Black/mixed/other 340 79 (23.2) 72 (21.2) 287 (84.4)

Marriage status 0.04 0.04 0.04

Unmarried 141 21 (14.9) 55 (39.0) 130 (92.2)

Married 503 115 (22.8) 86 (17.1) 431 (85.7)

Mother’s age 0.36 0.03 0.62

16–19 131 24 (18.3) 18 (13.7) 117 (89.3)

20–29 359 78 (21.7) 77 (21.4) 309 (86.1)

30–44 154 39 (35.3) 41 (26.6) 135 (87.6)

Obstetric complications 0.67 0.68 0.87

No 524 113 (21.5) 109 (20.8) 457 (87.2)

Yes 120 28 (23.3) 27 (22.5) 104 (86.7)

Number of pregnancies 0.79 0.13 0.006

1 222 52 (23.4) 40 (18.0) 205 (92.3)

2 198 42 (21.2) 39 (19.7) 172 (86.8)

3 or more 224 47 (21.0) 57 (25.4) 184 (82.1)

Breastfeeding (in months) 0.32 0.79 0.28

0–4 200 39 (19.5) 41 (20.5) 170 (85.0)

>5 444 102 (23.0) 95 (21.4) 391 (88.0)

BMI (kg/m2) 0.18 0.51 0.07

200–250 326 81(24.8) 63 (19.3) 292 (89.5)

154–199 41 8 (19.5) 10 (24.4) 32 (78.0)

251–414 277 52 (18.7) 63 (22.7) 237 (85.5)

Postnatal depression 0.15 0.000 0.000

No 465 95 (20.4) 60 (12.9) 430 (92.4)

Yes 179 46 (25.7) 76 (42.4) 131 (73.2)

Antenatal depression 0.76 0.02 0.001

No 445 96 (21.5) 83 (18.6) 401 (90.1)

Yes 199 45 (22.6) 53 (26.6) 160 (80.4)

Health problems 0.47 0.003 0.62

No 569 122 (21.4) 109 (19.1) 500 (87.8)

Yes 63 16 (25.4) 22 (34.9) 54 (85.7)

Timing of interview (months) 0.054 0.16 0.88

6–8 91 19 (20.9) 16 (17.6) 79 (86.8)

9–12 380 73 (19.2) 75 (19.7) 337 (88.7)

13–18 173 49 (28.3) 145 (26.0) 153 (88.4)

seventh month 95–100%, and in the thirteenth 19% of the couples resume intercourse within

month 97% of the couples [29]. Wide variations the first month after birth, 19% did not resume

have also been found in a prospective cohort with sexual life until 4 months after birth. In this study,

570 pregnant women interviewed in four occa- women reported that they resumed intercourse, on

sions, starting at the second trimester of pregnancy average, 7 weeks postpartum [1]. In Brazil, there is

and ending at 12 months after birth. Although no formal recommendation regarding the time to

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

6 Faisal-Cury et al.

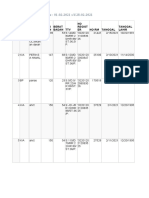

Table 2 Crude and adjusted associations of type of delivery with the sexual health outcomes

Later sexual resumption Decline of sexual life Presence of sexual desire

Crude Adjusted* Crude Adjusted† Crude Adjusted‡

RR/95% CI RR/95% CI RR/95% CI RR/95% CI RR/95% CI RR/95% CI

Type of delivery P = 0.73 P = 0.88 P = 0.04 P = 0.08 P = 0.08 P = 0.08

UVD 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

CVD 1.07 (0.72:1.59) 1.01(0.68:1.50) 0.57 (0.34:0.98) 0.62 (0.37:1.06) 1.07 (0.99:1.16) 1.00 (0.92:1.08)

CD 0.95 (0.68:1.32) 1.02 (0.74:.1.42) 0.97 (0.70:1.34) 0.88 (0.63:1.24) 1.03 (0.96:1.11) 0.99 (0.92:1.07)

*Marriage status, women’s body mass index (BMI).

†Marriage status, mother’s age, years of education, asset score, number of pregnancies, antenatal depression, health problem.

‡Monthly family income per capita, skin color, years of education, asset score, number of pregnancies, antenatal depression.

resume sexual life after delivery, and it remains the in the vagina, perineum, and rectum were all associ-

woman’s choice. ated with not resuming sexual life at 3 and 6 months

There is little agreement about the impact of after childbirth. No statistical differences were

MD on the resumption of sexual activity following found at 12-month follow-up [33]. In our study, we

childbirth. We did not find an association between did not find any difference in relation to the presence

vaginal delivery with episiotomy/perineal lacera- of desire and self-perception of DSL after childbirth.

tion or cesarean delivery with later resumption of It seems that an occasional decline in sexual desire in

sexual life. In accordance with the present study the postpartum period [34,35] may improve with

results, Hartmann et al. [30] reported that episi- time. Moreover, desire as well as pleasure is influ-

otomy did not affect the postpartum sexual func- enced by other important life issues such as body

tions of the women, and Rogers et al. [31] reported image, mother’s mental health, and marital relation-

that spontaneous perineal trauma was not associ- ship [36]. For example, breastfeeding has been asso-

ated with sexual dysfunction. Klein et al. [32] ciated with a delay in resumption of sexual activity

reported similar results as well. [37] and reports of a lack of sexual desire [1,38].

Other studies suggest that assisted vaginal deliv- Depression has also been implicated in the sexual

ery and cesarean section may delay sexual activity dysfunction after childbirth. In a previous publica-

after childbirth. A recent prospective pregnancy tion, we have shown that postpartum women with

cohort study of 1,507 nulliparous women found symptoms of depression/anxiety have more than

that 53% and 65% of women had resumed vaginal three times higher risk of reporting DSL after

sex by 6 and 8 weeks, respectively, and women who childbirth compared with women without these

had an operative vaginal birth, caesarean section or symptoms [39]. Morof et al. [40] evaluated the

perineal tear or episiotomy appear to delay longer sexual health experiences of both depressed and

[7]. Differences may be explained by the distinct nondepressed women. They found that women who

socio-demographic characteristics of the sample were depressed were less likely to have resumed

and by the obstetric procedures used in each study. intercourse by 6 months postpartum, engaged in less

Women in the Australian study were married, varied sexual activities and were more likely to report

older, and more educated than women in our sexual problems than nondepressed women. In the

study. Moreover, we have higher rates of cesarean present study, the lack of association between MD

delivery and spontaneous vaginal delivery. and sexual health outcomes did not change after

The timing of resumption of vaginal sex is only controlling for breastfeeding, antenatal, postnatal

one dimension of sexuality after childbirth. It may be depression, timing of interview in months (and other

more important to evaluate the impact of MD on covariates).

other aspects of women’s sexual health such as sexual The lack of association between MD and sexual

desire and pleasure. Regarding to the long-term functioning may be explained by the psychologi-

effects of MD on sexual functioning studies suggest cal, behavioral, and cultural factors that influence

that there is no significant difference at 12–18 sexuality after childbirth. Postpartum female

months after childbirth between women who deliv- sexual function is likely to be impacted by transi-

ered vaginally without episiotomy, heavy perineal tion to role as a mother, changes in body image,

laceration, operative interventions, and women who marital satisfaction, mood, fatigue, and anxiety or

underwent elective cesarean section [32]. This is in apprehension regarding the infant’s well-being

line with the results of a large population-based [41]. Serati et al. [42] have stated that sexual func-

study with 2,490 pregnant women in Sweden. Tears tion is dependent on many mechanisms associated

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

Mode of Delivery and Sexuality after Childbirth 7

more with psychological than organic factors. in the public sector and cannot be generalized to

According to Abdool [36], female sexual desire and other groups of postpartum women.

orgasmic disorders are a complex subject as they

encompass components of a subjective experience.

Although hormonal changes and peripartum trau- Conclusion

matic events may be part of this, it seems from the In this study, the MD had no impact on different

literature that it is short lived and self-limiting. sexual health outcomes, namely later resumption of

Despite the fact that the MD is not associated sexual life, presence of sexual desire, and decline of

with sexual health outcomes, sexual dysfunction sexual life after birth. Spontaneous uncomplicated

was quite frequent among our sample. DSL after or complicated vaginal delivery and cesarean deliv-

childbirth may have a negative impact on several ery had the same impact on sexuality evaluated up

domains of women’s life. Therefore, health pro- to 18 months after childbirth. Nevertheless, decline

fessionals should address sexuality concerns as an of sexual life is a relatively common occurrence

essential component in the practice standards after delivery, and efforts to recognize and treat this

during and beyond the postpartum period. It has problem should not focus only on MD.

been stated that healthcare workers need to be

aware of this silent suffering, as sexual morbidity

can have a detrimental effect on a women’s quality Acknowledgments

of life, as well on her social, physical, and emo- The study was funded by FAPESP (2003/08553-7).

tional well-being [36]. PRM was partially funded by the CNPq-Brazil.

Our study has some strengths, including a pro- AFC received postdoctoral fellowships from the

spective evaluation of sexual functioning up to CNPq-Brazil and FAPESP (2005/04572-2).

18 months after delivery and the representative

nature of our sample of pregnant women attending Corresponding Author: Alexandre Faisal-Cury, MD,

PhD, Departamento de Medicina Preventiva,

antenatal care in primary care units in the city of

Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, Av.

São Paulo, a large urban center in a middle- Dr. Arnaldo 455, São Paulo, SP CEP 01246-903, Brazil.

income country. Additionally, in relation to our Tel: 55-11-99362007; Fax: 55-11-36838196; E-mail:

exposure variable, MD, data were retrieved mostly lim39@usp.br; faisal@ip2.com.br

from public teaching hospital charts. In these hos-

pitals, the quality of medical data is good. Conflict of Interest: The author(s) report no conflicts of

interest.

Our study also has some limitations. First, the

assessment of our three sexual health outcomes

was based on a direct question, and we did not Statement of Authorship

include questions about dyspareunia and subjec-

tive reasons for sexual life decline. Moreover, we Category 1

cannot exclude the risk for recall bias considering (a) Conception and Design

the fact that many women may not feel comfort- Alexandre Faisal-Cury; Paulo Rossi Menezes

(b) Acquisition of Data

able or eager to report sexual problems. In this

Alexandre Faisal-Cury; Paulo Rossi Menezes

case, estimates would possibly be biased toward

(c) Analysis and Interpretation of Data

the null hypothesis. Some misclassification may

Alexandre Faisal-Cury; Alicia Matijasevich; Julieta

have occurred regarding to the lower rate of CVD Quayle, Simone Grilo Diniz

(16.3%). Although it may be explained by the

characteristic of both obstetric facilities, medical Category 2

teaching schools that praise normal delivery (a) Drafting the Article

(without episiotomy), it is known that perineal lac- Alexandre Faisal-Cury; Alicia Matijasevich; Julieta

erations grade 1 are frequently omitted by the Quayle, Simone Grilo Diniz

nurses or doctors. Second, we have complete data (b) Revising It for Intellectual Content

about sexual life for 77% (644 of 831) of the origi- Alexandre Faisal-Cury; Paulo Rossi Menezes, Alicia

nal sample of pregnant women. Third, as a result Matijasevich; Julieta Quayle, Simone Grilo Diniz

of the high incidence of female sexual dysfunction

in the nonpregnant female population, it would be Category 3

important to include assessment of sexual behavior (a) Final Approval of the Completed Article

before and during pregnancy. Lastly, our results Alexandre Faisal-Cury; Paulo Rossi Menezes; Alicia

were obtained from low income women attended Matijasevich; Julieta Quayle, Simone Grilo Diniz

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

8 Faisal-Cury et al.

References year after childbirth? BJOG 2006;113:914–8, (eng). PubMed

PMID: 16907937.

1 Byrd JE, Hyde JS, DeLamater JD, Plant EA. Sexuality 19 Reamy KJ, White SE. Sexuality in the puerperium: A review.

during pregnancy and the year postpartum. J Fam Pract Arch Sex Behav 1987;16:165–86, (eng). PubMed PMID:

1998;47:305–8, (eng). PubMed PMID: 9789517. 3592963.

2 Johnson CE. Sexual health during pregnancy and the postpar- 20 Barrett G, Peacock J, Victor CR, Manyonda I. Cesarean

tum. J Sex Med 2011;8:1267–84, quiz 85–6 (eng). PubMed section and postnatal sexual health. Birth 2005;32:306–11,

PMID: 21521481. (eng). PubMed PMID: 16336372.

3 Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, Victor C, Thakar R, 21 Liebling RE, Swingler R, Patel RR, Verity L, Soothill PW,

Manyonda I. Women’s sexual health after childbirth. Murphy DJ. Pelvic floor morbidity up to one year after

BJOG 2000;107:186–95, (eng). PubMed PMID: difficult instrumental delivery and cesarean section in the

10688502. second stage of labor: A cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol

4 Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bosch R, Fugl-Meyer AR, 2004;191:4–10, (eng). PubMed PMID: 15295337.

Laumann EO, Lizza E, Martin-Morales A. Epidemiology/risk 22 Bahl R, Strachan B, Murphy DJ. Pelvic floor morbidity at 3

factors of sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2004;1:35–9, (eng). years after instrumental delivery and cesarean delivery in the

PubMed PMID: 16422981. second stage of labor and the impact of a subsequent delivery.

5 Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, Repke JT. Postpar- Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:789–94, (eng). PubMed

tum sexual functioning and its relationship to perineal trauma: PMID: 15746673.

A retrospective cohort study of primiparous women. Am J 23 Hannah ME, Whyte H, Hannah WJ, Hewson S, Amankwah

Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:881–8, discussion 8–90. (eng). K, Cheng M, Gafni A, Guselle P, Helewa M, Hodnett ED,

PubMed PMID: 11303195. Hutton E, Kung R, McKay D, Ross S, Saigal S, Willan A;

6 Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Robbins JM, Kaczorowski J, Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Maternal outcomes at

Jorgensen SH, Franco ED, Johnson B, Waghorn K, Gelfand 2 years after planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal

MM, Guralnick MS, Gary WL, Arvind KJ. Relationship of birth for breech presentation at term: The international ran-

episiotomy to perineal trauma and morbidity, sexual dysfunc- domized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol

tion, and pelvic floor relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:917–27, (eng). PubMed PMID: 15467565.

1994;171:591–8, (eng). PubMed PMID: 8092203. 24 Botros SM, Abramov Y, Miller JJ, Sand PK, Gandhi S,

7 McDonald EA, Brown SJ. Does method of birth make a Nickolov A, Goldberg RP. Effect of parity on sexual function:

difference to when women resume sex after childbirth? An identical twin study. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:765–70,

BJOG 2013;120:823–30, (eng). PubMed PMID: 23442053. (eng). PubMed PMID: 16582110.

8 Andrews V, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Jones PW. Evaluation of 25 Faisal-Cury A, Menezes P, Araya R, Zugaib M. Common

postpartum perineal pain and dyspareunia—A prospective mental disorders during pregnancy: Prevalence and associated

study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;137:152–6, factors among low-income women in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Arch

(eng). PubMed PMID: 17681663. Womens Ment Health 2009;12:335–43. PubMed PMID:

9 Rogers RG, Leeman LM, Migliaccio L, Albers LL. Does WOS:000270663900009.

the severity of spontaneous genital tract trauma affect 26 Harding TW, de Arango MV, Baltazar J, Climent CE,

postpartum pelvic floor function? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Ibrahim HH, Ladrido-Ignacio L, Murthy RS, Wig NN.

Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:429–35, (eng). PubMed PMID: Mental disorders in primary health care: A study of their fre-

17896065. quency and diagnosis in four developing countries. Psychol

10 Handa VL. Sexual function and childbirth. Semin Perinatol Med 1980;10:231–41, (eng). PubMed PMID: 7384326.

2006;30:253–6, (eng). PubMed PMID: 17011395. 27 Mari JJ, Williams P. A validity study of a psychiatric screening

11 Clark MH, Scott M, Vogt V, Benson JT. Monitoring pudendal questionnaire (SRQ-20) in primary care in the city of Sao

nerve function during labor. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:637–9, Paulo. Br J Psychiatry 1986;148:23–6, (eng). PubMed PMID:

(eng). PubMed PMID: 11294173. 3955316.

12 Lee SJ, Park JW. Follow-up evaluation of the effect of 28 Pollock JI, Manaseki-Holland S, Patel V. Detection of

vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor. Dis Colon Rectum depression in women of child-bearing age in non-Western

2000;43:1550–5, (eng). PubMed PMID: 11089591. cultures: A comparison of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression

13 Abraham S. Recovery after childbirth. Med J Aust Scale and the Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20 in Mongolia.

1990;152:387, (eng). PubMed PMID: 2093822. J Affect Disord 2006;92:267–71, (eng). PubMed PMID:

14 Clarkson J, Newton C, Bick D, Gyte G, Kettle C, Newburn 16616376.

M, Radford J, Johanson R. Achieving sustainable quality in 29 von Sydow K. Sexuality during pregnancy and after childbirth:

maternity services—Using audit of incontinence and dyspareu- A metacontent analysis of 59 studies. J Psychosom Res

nia to identify shortfalls in meeting standards. BMC Preg- 1999;47:27–49, (eng). PubMed PMID: 10511419.

nancy Childbirth 2001;1:4, (ENG). PubMed PMID: 30 Hartmann K, Viswanathan M, Palmieri R, Gartlehner G,

11710963. PMCID: PMC59837. Thorp J, Lohr KN. Outcomes of routine episiotomy: A sys-

15 Hicks TL, Goodall SF, Quattrone EM, Lydon-Rochelle MT. tematic review. JAMA 2005;293:2141–8, (eng). PubMed

Postpartum sexual functioning and method of delivery: PMID: 15870418.

Summary of the evidence. J Midwifery Womens Health 31 Rogers RG, Borders N, Leeman LM, Albers LL. Does

2004;49:430–6, (eng). PubMed PMID: 15351333. spontaneous genital tract trauma impact postpartum

16 Leeman LM, Rogers RG. Sex after childbirth: Postpartum sexual function? J Midwifery Womens Health 2009;54:98–103,

sexual function. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:647–55, (eng). (eng). PubMed PMID: 19249654. PMCID: PMC2730880.

PubMed PMID: 22353966. 32 Klein K, Worda C, Leipold H, Gruber C, Husslein P, Wenzl

17 Ejegård H, Ryding EL, Sjogren B. Sexuality after delivery with R. Does the mode of delivery influence sexual function after

episiotomy: A long-term follow-up. Gynecol Obstet Invest childbirth? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1227–31,

2008;66:1–7, (eng). PubMed PMID: 18204265. (eng). PubMed PMID: 19630552.

18 van Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, van de Pol G, Heintz AP, van 33 Rådestad I, Olsson A, Nissen E, Rubertsson C. Tears in the

der Vaart CH. Which factors determine the sexual function 1 vagina, perineum, sphincter ani, and rectum and first sexual

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

Mode of Delivery and Sexuality after Childbirth 9

intercourse after childbirth: A nationwide follow-up. Birth J Midwifery Womens Health 2000;45:227–37, (eng). PubMed

2008;35:98–106, (eng). PubMed PMID: 18507580. PMID: 10907332.

34 Elliott SA, Watson JP. Sex during pregnancy and the first 39 Faisal-Cury A, Huang H, Chan YF, Menezes PR. The

postnatal year. J Psychosom Res 1985;29:541–8, (eng). relationship between depressive/anxiety symptoms during

PubMed PMID: 4067892. pregnancy/postpartum and sexual life decline after delivery. J

35 Reading AE, Sledmere CM, Cox DN, Campbell S. How Sex Med 2013;10:1343–9, (eng). PubMed PMID: 23433352.

women view postepisiotomy pain. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) PMCID: PMC3727156.

1982;284:243–6, (eng). PubMed PMID: 6799123. PMCID: 40 Morof D, Barrett G, Peacock J, Victor CR, Manyonda I.

PMC1495830. Postnatal depression and sexual health after childbirth.

36 Abdool Z, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Postpartum female sexual Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:1318–25, (eng). PubMed PMID:

function. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;145:133–7, 14662221.

(eng). PubMed PMID: 19481858. 41 DeJudicibus MA, McCabe MP. Psychological factors and the

37 Rowland M, Foxcroft L, Hopman WM, Patel R. Breastfeeding sexuality of pregnant and postpartum women. J Sex Res

and sexuality immediately post partum. Can Fam Physician 2002;39:94–103, (eng). PubMed PMID: 12476241.

2005;51:1366–7, (eng). PubMed PMID: 16926969. PMCID: 42 Serati M, Salvatore S, Siesto G, Cattoni E, Zanirato M,

PMC1479788. Khullar V, Cromi A, Ghezzi F, Bolis P. Female sexual function

38 Avery MD, Duckett L, Frantzich CR. The experience of during pregnancy and after childbirth. J Sex Med 2010;7:2782–

sexuality during breastfeeding among primiparous women. 90, (eng). PubMed PMID: 20626601.

J Sex Med **;**:**–**

View publication stats

You might also like

- Katherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1Document4 pagesKatherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1angelie21No ratings yet

- Uterine RuptureDocument21 pagesUterine RuptureSirisha Pemma100% (7)

- Lag Aert 2017Document8 pagesLag Aert 2017abdi syahputraNo ratings yet

- Male ParticipationDocument12 pagesMale Participationsiska khairNo ratings yet

- Factors in Uencing Couples' Sexuality in The Puerperium: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesFactors in Uencing Couples' Sexuality in The Puerperium: A Systematic ReviewIonela BogdanNo ratings yet

- Sexual - Life - and - Dysfunction - After - Maternal - Morbidi BGFNBRNDocument14 pagesSexual - Life - and - Dysfunction - After - Maternal - Morbidi BGFNBRNOctaria SaputraNo ratings yet

- 1 Monteiro Etal 2021Document6 pages1 Monteiro Etal 2021Gabriel GursenNo ratings yet

- 06 Chapter 2Document48 pages06 Chapter 2Prakash BalagurunathanNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Floor Healing Milestones After Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury: A Prospective Case Control Feasibility StudyDocument9 pagesPelvic Floor Healing Milestones After Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury: A Prospective Case Control Feasibility Studywijana410No ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Menstrual Cycle Irregularity and MenopauseDocument11 pagesFactors Associated With Menstrual Cycle Irregularity and MenopauseRyan IlhamNo ratings yet

- Zhou2009 Article DesignOfAQuestionnaireForEvaluDocument12 pagesZhou2009 Article DesignOfAQuestionnaireForEvalufatihnkNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Floor Muscle Strength in Primiparous Women According To The Delivery Type: Cross-Sectional StudyDocument9 pagesPelvic Floor Muscle Strength in Primiparous Women According To The Delivery Type: Cross-Sectional StudySarnisyah Dwi MartianiNo ratings yet

- Urinary Incontinence in Pregnant Women: Integrative Review: Open Journal of Nursing, 2016, 6, 229-238Document10 pagesUrinary Incontinence in Pregnant Women: Integrative Review: Open Journal of Nursing, 2016, 6, 229-238Diana AstriaNo ratings yet

- Changes in The Sexual Function During Pregnancy: Aim. MethodsDocument10 pagesChanges in The Sexual Function During Pregnancy: Aim. MethodsYosep SutandarNo ratings yet

- Cancer NursingDocument11 pagesCancer NursingAsia SzmyłaNo ratings yet

- Optimal Birth Spacing: What Can We Measure and What Do We Want To Know?Document3 pagesOptimal Birth Spacing: What Can We Measure and What Do We Want To Know?rizmahNo ratings yet

- Research Article:: Postnatal Quality of Life in Women Aftr Normal Vaginal Delivery and Caesarean SectionDocument2 pagesResearch Article:: Postnatal Quality of Life in Women Aftr Normal Vaginal Delivery and Caesarean SectionTORRES Hazel Ann I.No ratings yet

- Adverse Childhood Experiences and Repeat Induced Abortion: General GynecologyDocument6 pagesAdverse Childhood Experiences and Repeat Induced Abortion: General Gynecologychie_8866No ratings yet

- BJOG - 2005 - Bartellas - Sexuality and Sexual Activity in PregnancyDocument5 pagesBJOG - 2005 - Bartellas - Sexuality and Sexual Activity in Pregnancyศุภชัย ศิลาวัชรพลNo ratings yet

- Amicus Brief To The InterAmerican Court of Human RightsDocument17 pagesAmicus Brief To The InterAmerican Court of Human RightsMeica MagosNo ratings yet

- Aerts Et Al 2014Document8 pagesAerts Et Al 2014chatsashNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument12 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyCristina ToaderNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Duration .BreastfeedingDocument14 pagesPredictors of Duration .BreastfeedingJihan Nadila AsriNo ratings yet

- Infertility and Life Satisfaction Among WomenDocument29 pagesInfertility and Life Satisfaction Among WomenIshrat PatelNo ratings yet

- Infertility Project PDFDocument11 pagesInfertility Project PDFSunil KumarNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1049386713001060 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S1049386713001060 Mainannisa.indriyaniNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Psychosocial Interventions On The Mental Health, Pregnancy RatesDocument13 pagesThe Effects of Psychosocial Interventions On The Mental Health, Pregnancy RatesMaria Galia Elias QuirogaNo ratings yet

- Reproductive Health: Maternal Position During The First Stage of Labor: A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesReproductive Health: Maternal Position During The First Stage of Labor: A Systematic ReviewDyah AgNo ratings yet

- Javon WitherspoonDocument6 pagesJavon Witherspoonapi-445367279No ratings yet

- BHP Williams 2012Document6 pagesBHP Williams 2012AnyaNo ratings yet

- Nalses: Psychological Conditions and Their Relevance Sterilization: ReviewDocument12 pagesNalses: Psychological Conditions and Their Relevance Sterilization: ReviewAdriana MeloNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Resilience or Vulnerability To Hot Flushes and Night Sweats During The Menopausal TransitionDocument28 pagesFactors Associated With Resilience or Vulnerability To Hot Flushes and Night Sweats During The Menopausal TransitionKhoiro QonitaNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument19 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptErna Jovem GluberryNo ratings yet

- Aerobic Exercise, Mood States and Menstrual Cycle Symptoms: Epublications@BondDocument13 pagesAerobic Exercise, Mood States and Menstrual Cycle Symptoms: Epublications@BondPilarRubioFernándezNo ratings yet

- Endo Met RitisDocument9 pagesEndo Met RitisabdullahNo ratings yet

- Endo Met RitisDocument9 pagesEndo Met RitisabdullahNo ratings yet

- Age As The Risk Factor That Affected The Increased Degree of Uterine ProlapseDocument5 pagesAge As The Risk Factor That Affected The Increased Degree of Uterine Prolapsehypebeast dopeNo ratings yet

- Neri Journal R DutyDocument5 pagesNeri Journal R DutyAnamarcel Barillo NeriNo ratings yet

- Annals of Epidemiology: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesAnnals of Epidemiology: Original Articleoktavia mandaaNo ratings yet

- Author Information Kafaei Atrian MDocument9 pagesAuthor Information Kafaei Atrian MabdullahNo ratings yet

- Journal Uro 1Document15 pagesJournal Uro 1Gladys AilingNo ratings yet

- Bvaa 131Document10 pagesBvaa 131Sthephany AndreinaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Stress On The Menstrual CycleDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Stress On The Menstrual Cyclemaria paula brenesNo ratings yet

- Articulo Peruano PDFDocument10 pagesArticulo Peruano PDFStephanyChavezFeriaNo ratings yet

- 192 2013 Article 2061Document12 pages192 2013 Article 2061siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Desk Study Report - Group 2Document18 pagesDesk Study Report - Group 2api-660098543No ratings yet

- Healthcare Decisionmaking Targeting Women As Leaders of Change For Population Health 2376 127X 1000221Document7 pagesHealthcare Decisionmaking Targeting Women As Leaders of Change For Population Health 2376 127X 1000221Arifah UsrahNo ratings yet

- Infertilitas Pasangan Usia Subur Di Klinik Rumah BundaDocument15 pagesInfertilitas Pasangan Usia Subur Di Klinik Rumah Bundakelas bidanNo ratings yet

- The Quality of Life of Women SufferDocument8 pagesThe Quality of Life of Women SufferKritika AgarwalNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Abortion On Having and Achieving Aspirational One-Year PlansDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Abortion On Having and Achieving Aspirational One-Year PlansAhlfea JugalbotNo ratings yet

- Perception ChildbearingDocument18 pagesPerception ChildbearingnorjumawatonshahruddNo ratings yet

- Author Information Kafaei Atrian MDocument9 pagesAuthor Information Kafaei Atrian MabdullahNo ratings yet

- Demographic Research: Volume 32, Article 4, Pages 107 Published 9 January 2015Document42 pagesDemographic Research: Volume 32, Article 4, Pages 107 Published 9 January 2015paaztiiNo ratings yet

- Etiology and Risk Factors of Female Infertility in Pravara Rural Hospital, LoniDocument9 pagesEtiology and Risk Factors of Female Infertility in Pravara Rural Hospital, LoniIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Maternal Nursing Care - CHPT 6 Human Sexuality and FertilityDocument28 pagesMaternal Nursing Care - CHPT 6 Human Sexuality and Fertilitythubtendrolma100% (1)

- Toksemia GravidarumDocument9 pagesToksemia GravidarumabdullahNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study To Assess The Quality of Life Among Mothers After Normal Vaginal Delivery and Caesarean SectionDocument4 pagesA Comparative Study To Assess The Quality of Life Among Mothers After Normal Vaginal Delivery and Caesarean SectionEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence Among Post-MenoDocument11 pagesPrevalence of Urinary Incontinence Among Post-MenoAquarelle Prothesiste OngulaireNo ratings yet

- Author Information Kafaei Atrian MDocument9 pagesAuthor Information Kafaei Atrian MabdullahNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Effects of Kegel Exercises Applied To Urinary Incontinence On Sexual SatisfactionDocument10 pagesOriginal Article: Effects of Kegel Exercises Applied To Urinary Incontinence On Sexual SatisfactionAnonymous XxK0PcDEsNo ratings yet

- Kegels Are Not Going to Fix This: The latest medical understanding of pelvic floor disorders and their impact on quality of lifeFrom EverandKegels Are Not Going to Fix This: The latest medical understanding of pelvic floor disorders and their impact on quality of lifeNo ratings yet

- Preconception Health Care InterventionsDocument26 pagesPreconception Health Care Interventionssipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Preconception Care ofDocument11 pagesPreconception Care ofsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Early Mobilization, Early Breastfeeding Initiation, and Oxytocin Massage Against Uterine InvolutionDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of Early Mobilization, Early Breastfeeding Initiation, and Oxytocin Massage Against Uterine Involutionsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Preconception Care ForDocument10 pagesPreconception Care Forsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Eb PreconsepsiDocument246 pagesEb Preconsepsisipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Abdul Sattarkhudhurali2018Document7 pagesAbdul Sattarkhudhurali2018KimIstiRisHwaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Pregnancy On Endometriosis - Facts or Fiction?Document10 pagesThe Effect of Pregnancy On Endometriosis - Facts or Fiction?sipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Yoga For Hypertension Posadzki2014Document12 pagesYoga For Hypertension Posadzki2014sipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Sexual Disfungtion BreastfeedingDocument9 pagesSexual Disfungtion Breastfeedingsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Pelvic Floor Muscle ExerciseDocument16 pagesThe Effect of Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercisesipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- NIFAS Aktivitas Fisik Dan Terjadinya DPPDocument16 pagesNIFAS Aktivitas Fisik Dan Terjadinya DPPsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- NIFAS Aktivitas Fisik Dan Terjadinya DPPDocument16 pagesNIFAS Aktivitas Fisik Dan Terjadinya DPPsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Sexologi Post PartumDocument10 pagesJurnal Sexologi Post PartumEndrianus Jaya PutraNo ratings yet

- WHO RHR 18.04 EngDocument106 pagesWHO RHR 18.04 EngabydlNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: Aderonke Oyetunji, Prakash Chandra TDocument9 pagesPsychiatry Research: Aderonke Oyetunji, Prakash Chandra Tsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Sexual Activity and DysfungtionDocument11 pagesSexual Activity and Dysfungtionsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Judul Jurnal IpbDocument1 pageJudul Jurnal Ipbsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Judul Jurnal IpbDocument1 pageJudul Jurnal Ipbsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- s12884 018 1667 7Document11 pagess12884 018 1667 7sipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- ANAK Efek Intervensi Perkembangan AnakDocument8 pagesANAK Efek Intervensi Perkembangan Anaksipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Faktor Resiko DPP 2020Document13 pagesFaktor Resiko DPP 2020sipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- ANAK Efek Intervensi Perkembangan AnakDocument8 pagesANAK Efek Intervensi Perkembangan Anaksipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Sexual Disfungtion BreastfeedingDocument9 pagesSexual Disfungtion Breastfeedingsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- 1Document12 pages1sipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- 1Document12 pages1sipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Pre Test 7-9Document10 pagesPre Test 7-9Naomi VirtudazoNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Effect of Antenatal Betamethasone On Neonatal Respiratory Morbidities in Late Preterm Deliveries (34-37 Weeks)Document9 pagesEvaluation of The Effect of Antenatal Betamethasone On Neonatal Respiratory Morbidities in Late Preterm Deliveries (34-37 Weeks)Rizka RamadaniNo ratings yet

- Placental AbruptionDocument34 pagesPlacental Abruptionrosekatekate929No ratings yet

- ANTEPARTUM HEMORRHAGE - Afina RazibDocument11 pagesANTEPARTUM HEMORRHAGE - Afina Razibرفاعي آكرمNo ratings yet

- Fetal SurvillanceDocument26 pagesFetal SurvillanceBetelhem EjiguNo ratings yet

- Planned Caesarean: What Are The Health Effects of Mother and Child?Document30 pagesPlanned Caesarean: What Are The Health Effects of Mother and Child?Komal KhanNo ratings yet

- High Risk PregnancyDocument71 pagesHigh Risk PregnancyGERALDINE TENECLANNo ratings yet

- Epic InstructionsDocument3 pagesEpic Instructionserik_romanelliNo ratings yet

- A Short History of MidwiferyDocument5 pagesA Short History of MidwiferyaarthiashokNo ratings yet

- Post-Partum Hemorrhage Pathophysiology PaperDocument5 pagesPost-Partum Hemorrhage Pathophysiology Paperapi-399619969No ratings yet

- Cervical Incompetence: Risk FactorsDocument40 pagesCervical Incompetence: Risk FactorsAriaPratamaNo ratings yet

- 10 The Role of Routine Cervical Length Screening in Selected High - and Low-Risk Women For Preterm Birth PreventionDocument6 pages10 The Role of Routine Cervical Length Screening in Selected High - and Low-Risk Women For Preterm Birth PreventionWailea Faye SalvaNo ratings yet

- Queen's SquareDocument45 pagesQueen's SquareGarifuna NationNo ratings yet

- Animal Form and Function Gen Bio IIDocument73 pagesAnimal Form and Function Gen Bio IIPalad , John Carlo BernabeNo ratings yet

- Silabus S1 KebidananDocument14 pagesSilabus S1 KebidananCindymarinapjNo ratings yet

- Management Placenta PreviaDocument24 pagesManagement Placenta PreviaMuhammad RifaldiNo ratings yet

- Determining Gravidity and ParityDocument25 pagesDetermining Gravidity and ParityRon Ar IcaNo ratings yet

- Lake IndependenceDocument81 pagesLake IndependenceGarifuna NationNo ratings yet

- Uterine Hyperstimulation, Management of - ABMU Maternity Guideline 2018Document7 pagesUterine Hyperstimulation, Management of - ABMU Maternity Guideline 2018Chintya MarcellinNo ratings yet

- Newborn Care: A Newborn Baby or Animal Is One That Has Just Been BornDocument26 pagesNewborn Care: A Newborn Baby or Animal Is One That Has Just Been BornJenny-Vi Tegelan LandayanNo ratings yet

- Third Stage of LabourDocument29 pagesThird Stage of LabourAyanayuNo ratings yet

- Reff. Maji Natitu To Mb/R/3 TMK, Muhimbili 2021 Majernity: Total .Reff. Janyary 2021. Total Reff. February 2021Document5 pagesReff. Maji Natitu To Mb/R/3 TMK, Muhimbili 2021 Majernity: Total .Reff. Janyary 2021. Total Reff. February 2021EMNY KATAMWANo ratings yet

- Hubungan Antara Panjang, Insersi, Dan Indeks Pilinan Tali Pusat Terhadap Berat Badan Lahir Pada Persalinan Preterm Di RSUP Sanglah, Denpasar, BaliDocument5 pagesHubungan Antara Panjang, Insersi, Dan Indeks Pilinan Tali Pusat Terhadap Berat Badan Lahir Pada Persalinan Preterm Di RSUP Sanglah, Denpasar, BaliGufront MustofaNo ratings yet

- Subject: Field Observation Report: Pphi SindhDocument2 pagesSubject: Field Observation Report: Pphi Sindhrafique512No ratings yet

- PartographDocument38 pagesPartographsushmita yadavNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Maternal Health Literacy and Pregnancy OutcomeDocument11 pagesThe Relationship Between Maternal Health Literacy and Pregnancy Outcome1854 Joshua LallawmsangaNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kunjungan Pustu KlampokDocument61 pagesLaporan Kunjungan Pustu Klampokranggie nindya slamanthaNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine ActionDocument9 pagesAbnormal Uterine ActionAnu ThomasNo ratings yet

- The Perinatal MortalityDocument38 pagesThe Perinatal MortalityMed PoxNo ratings yet