Professional Documents

Culture Documents

More Control, Less Con Ict? Job Demand-Control, Gender and Work-Family Con Ict

Uploaded by

putrifaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

More Control, Less Con Ict? Job Demand-Control, Gender and Work-Family Con Ict

Uploaded by

putrifaCopyright:

Available Formats

Gender, Work and Organization. Vol. 14 No.

5 September 2007

More Control, Less Conflict? Job

Demand–Control, Gender and

Work–Family Conflict

Anne Grönlund*

The connection between working hours and work-to-family conflict has

been established in a number of studies. However, it seems what is impor-

tant is not only the quantity of work but also its quality, as captured by the

job demand–control model. Survey data from 800 Swedish employees

show that job demands spill over negatively into family life, while job

control reduces work-to-family conflict. Interestingly, women in jobs with

high demands and high control — regarded as the prototype for modern,

flexible work life — do not experience more work-to-family conflict than

men, even when working the same hours.

Keywords: work-to-family conflict, job demand–control model, gender

Introduction

T he aim of this article is to study how the psychosocial work environment

influences the possibility of combining paid work and family life. It

presents a new approach, for most previous research on work and stress has

stopped at the company gates, while research on work–family conflict has

stayed on the other side of those gates, focusing on working hours and largely

ignoring the theories used in research on work stress.

The issue is important because the balancing of work and family is a

potential source of stress. To the extent that the work environment affects this

balancing act, it may have unacknowledged effects on health, as well as on

gender equality. Further integration of research on work and family may also

contribute to the development of theories that better describe a situation

where women’s participation in the labour force approaches that of men,

making the notion of separate spheres seem increasingly outdated.

Address for correspondence: *Department of Sociology, Umeå University, 901 87, Umeå Unver-

sity, Sweden, e-mail: Anne.Gronlund@soc.umu.se

© 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 477

Two fields of research

This article brings together insights from two fields of research, the field of

work and stress and that of work–family conflict, in an empirical analysis of

how the psychosocial work environment, measured by the demand–control

model, affects family life for men and women.

The job demand–control model

Control has become a key word in both academic and public debate about the

relationship between work and stress. In the demand–control model, the

theoretical model that has dominated this research field for more than 25

years, the concept of control refers to the decision latitude employees have in

their job (Karasek, 1979; Karasek and Theorell, 1990). According to this

model, it is control (that is, the extent to which employees can control the pace

of work, decide when and how to perform different tasks and have a say in

policy decisions) that separates good jobs from bad ones. A job with high

demands and low control is ‘high strain’, while a job high in control and low

in demands is ‘low strain’. However, high job demands do not necessarily

lead to stress if the employee has a high degree of control. Such active jobs are

also optimal for learning and therefore employees will develop ever better

strategies for dealing with the job demands. By contrast, in high strain jobs

the constant stress inhibits learning, causing strain to accumulate. In the

fourth category of the model, the passive job, the problem is not stress but

passivity and learned helplessness (see Figure 1).

Over the years a number of researchers have used the job demand–control

model to analyse the relationship between the psychosocial work environ-

ment and different stress-related problems ranging from cardiovascular

disease to musculoskeletal symptoms, irritable bowel syndrome and psycho-

logical distress. A review of the research on psychological distress shows that

the model has been supported in many, but far from all, studies (van der Doef

and Maes, 1999).

The lack of unanimity may partly be due to the fact that different hypoth-

eses can be derived from the model. The strain hypothesis states that, because

job demands increase stress and job control reduces it, high strain jobs are the

Job demands

Low High

Job High Low strain work Active work

control Low Passive work High strain work

Figure 1: The demand–control model (Karasek and Theorell, 1990)

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

478 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

most stressful. This hypothesis has been confirmed in many studies, but the

comparison is generally with low strain jobs and is it not always clear whether

the outcome is produced exclusively by the high demands or the low control,

whether both contribute independently to the outcome or whether they have

a synergistic relationship, producing a strain greater than the additive effect

(van der Doef and Maes, 1999; Fletcher and Jones, 1993). The buffer hypoth-

esis, which can be regarded as a further specification of the strain hypothesis,

claims that control can moderate the negative effect of high demands or, in

other words, that the effect of demands varies with the level of control.

This hypothesis has received less support than tests of additative effects

(van der Doef and Maes, 1999; Fletcher and Jones, 1993; Ganster and Fusilier,

1989; Sauter et al., 1989; Wallace, 2005; Warr, 1990 — but see Wall et al., 1996)

and the question of how the stress-reducing power of control should be

tested has been debated at length (Fletcher and Jones, 1993; Ganster and

Fusilier, 1989; Karasek, 1979, 1989; Landsbergis et al., 1995; Spector, 1998;

Wall et al., 1996). However, the designer of the model, Robert Karasek, states

that ‘for the demand–control model, the existence of a multiplicative interac-

tion term is not the primary issue’, because ‘the practical implications for job

redesign are largely unchanged if two separate linear effects for control and

demand are observed’ (Karasek, 1989, p. 143).1

In this article, both hypotheses will be tested. Firstly, the independent,

additative effects of demand and control will be examined. As Karasek notes,

these are interesting in themselves and this is especially true when the model

is applied to a new area, in this case, work–family conflict. In a second step,

I will examine the interactive effects of demand and control, both by com-

paring the job types described in Figure 1 and by using a multiplicative

interaction term. Taken together, this should provide a quite comprehensive

test of the model.

Work–family conflict

Demands for presence and commitment do not come only from work but also

from the home, and increased female labour participation has meant that the

effort to combine the two spheres has become a daily challenge to a great

number of people.

The balancing of paid work and family is also an expanding field of

research, with two basic hypotheses. The role-strain hypothesis states that

multiple roles create stressful conflict. The basic premise is that people have

limited time and energy, and thus the more roles they have to fulfil, the

greater the need to set priorities and negotiate with other parties and, conse-

quently, the smaller the chance of meeting all expectations (Goode, 1960;

Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). By contrast, the expansion hypothesis claims

that multiple roles can serve as a buffer against stress (Sieber, 1974; Thoits,

1983). In terms of this hypothesis, a role also brings privileges that are not

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 479

accompanied by requests for performance. One of these privileges is the

possibility to ‘role bargain’, trading off obligations in one role by invoking the

demands of another. Moreover, the feeling of being needed and appreciated

in different contexts can strengthen self-esteem and create a sense of security,

for problems and failures in one sphere can be compensated for by success

and satisfaction in the other.

These hypotheses have been competing for credibility and both have been

supported by empirical research. Several studies show that longer working

hours increase the perceived level of work–family conflict as well as psycho-

logical distress in general (Fenwick and Tausig, 2001; Fredriksen-Goldsen

and Scharlach, 2001; Grönlund, 2004; Kinnunen and Mauno, 1998; Voydanoff,

1988). A higher class position or income (Fenwick and Tausig, 2001;

Fredriksen-Goldsen and Scharlach, 2001; Grönlund, 2004; Kinnunen and

Mauno, 1998; Nordenmark, 2002; Voydanoff, 1988), as well as more or

younger children (Grönlund, 2004; Kinnunen and Mauno, 1998; Lundberg

et al., 1994; Lundberg and Frankenhaeuser, 1999; Moen and Yu, 1999;

Voydanoff, 1988), also increase conflict and distress. In each of these

instances, however, there are divergent results (for working hours see

Härenstam and Bejerot, 2001; Moen and Yu, 1999; Nordenmark, 2002; for

class position see Moen and Yu, 1999; for children see Karasek et al., 1987;

Nordenmark, 2002). The latter findings, as well as studies showing that

working wives experience less psychological distress than housewives

(Lennon and Rosenfield, 1992) or that more roles mean fewer mental prob-

lems (Thoits, 1983) may be regarded as support for the expansion hypothesis.

However, they could also be the result of selection in labour or family

‘markets’. In other words, people who successfully combine work and family

may have been functioning better to start with (Bolger et al., 1990).

The contradictory results also suggest that the ‘either–or’ argument of the

two hypotheses has become increasingly irrelevant, considering that the

number of dual-earner couples has grown dramatically in recent decades

(Pitt-Catsouphes et al., 2006). Also, as other researchers have pointed out, it

may be more reasonable to assume that multiple roles in paid work and

family are positive, up to the point when the demands grow too heavy

(Fredriksen-Goldsen and Scharlach, 2001; Härenstam et al., 2000). The inter-

esting issue, then, is under what circumstances multiple roles are stimulating

and when and how they become a problem.

A crucial question, however, is how to define ‘demands’. Whereas the

theory speaks of a role conflict, empirical studies present the problem largely

as a time conflict. Although measures of workload have been included in

several studies (see Byron, 2005; Fredriksen-Goldsen and Scharlach, 2001;

Moen and Yu, 1999; Voydanoff, 1988), the insights from research on work and

stress have not been thoroughly considered. Still, it seems reasonable to

assume that combining work and family is not only a question of time

(Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). Although a heavy workload may cause a stress

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

480 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

that invades private life, job control may provide a means to limit the prob-

lems. In fact, if job control can turn stressful demands into positive chal-

lenges, the level of control may determine whether a strong commitment to

both work and family will lead to strain or gain.

However, control may not have this beneficial effect. According to several

researchers, efforts to increase organizational flexibility have loosened the

regulation of work, leaving it up to individual employees to define their goals,

prioritize different tasks and draw the line between work and private life

(Allvin, 1997; Allvin and Aronsson, 2003; Allvin et al., 1999, Beck, 1998; Elvin-

Nowak, 1998; Garhammer, 1995; Hanson, 2004). This freedom can become a

burden, for personal responsibility for complex problems may cause feelings

of guilt and failure (Elvin-Nowak, 1998; Spector, 1998). The balancing of work

and family is a case in point. In the modern, ‘temporary negotiation family’

(Beck, 1998, p. 122) the roles, the division of labour and, ultimately, the

relationship itself are under constant scrutiny and negotiations are compli-

cated by the fact that many organizations expect strong commitment from their

employees (Hochschild, 1997). In fact, employee control and participation may

be used as a means to strengthen commitment and so, in the work–family

loyalty competition, control may contribute to a feeling of insufficiency.

Empirically, the effect of job control on work–family conflict has been little

investigated. In a study of married American women, Lennon and Rosenfield

(1992) show that women with a high degree of job control have fewer stress

symptoms than housewives and that control moderates the stressful effect of

having more children. In a few other studies, however, control has no sig-

nificant effect on work–family conflict (Fredriksen-Goldsen and Scharlach,

2001; Kinnunen and Mauno, 1998; Moen and Yu, 1999) and control has not

been considered in relation to job demands. Wallace (2005) discusses the

relevance of the demand–control model to work–family conflict, but only

measures the control of working time, a variable not included in the original

model. Voydanoff (1988) examines the interaction between job demands and

job control, but does not discuss the main effects of demand and control. Also,

with data from 1977, the study’s results may be affected by selection effects

(see data section in this article). At that time, female labour force participation

was considerably lower than today2 and women often did not work during

the child-rearing years (OECD, 2002). On a more general level, both work and

family life have gone through considerable changes over the past three

decades, as sketched out above. Therefore, it is of great interest to examine

how job control may influence work–family conflict in the 20th century and

whether control can moderate the negative effect of job demands.

The significance of gender

Another unexplored issue is whether job demands and job control have the

same impact on women and men. Some research has shown gendered effects

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 481

on psychological wellbeing as well as on cardiovascular disease, but the

results are inconclusive: while some studies show that the effect is weaker

among women, others find it to be stronger (van der Doef and Maes, 1999;

Karasek et al., 1987; Karasek and Theorell, 1990). In either case, the standard

explanation is that the gendered division of unpaid work complicates the

work–health relationship for women. The fact that women still carry the main

responsibility for childcare and housework (Bianchi et al., 2000; Statistiska

Centralbyrån SCB, 2003) is also cited when women report more stress, show

higher levels of stress hormones and experience more work–family conflict

than men who have the same number of working hours (Fenwick and Tausig,

2001; Fredriksen-Goldsen and Scharlach, 2001; Greenhaus et al., 1987;

Grönlund, 2004; Gutek et al., 1991; Härenstam and Bejerot, 2001; Lundberg

and Frankenhaeuser, 1999; Lundberg et al., 1994; Nordenmark, 2002; Shinn

et al., 1989). However, such gender differences may also be influenced by the

fact that women generally have lower positions and less control over their

own work (Karasek and Theorell, 1990). Therefore, it is a shortcoming that

work stress and family stress have been considered two separate fields of

research.

The perception of work–family conflict may also, as other researchers have

pointed out, be shaped by stereotypical notions of gender roles (Barnett and

Baruch, 1987; Gutek et al., 1991). Traditionally, men have fulfilled their family

responsibilities by being good providers. To some extent, therefore, the com-

bination of work and family could have a synergistic effect for men, as ‘having

a job makes it possible to discharge family responsibilities; having a family

makes work meaningful’ (Barnett and Baruch, 1987, p. 130). Women may have

less scope for such role bargaining, both because they generally have a lower

position and income than their partner and because the social construction of

gender makes motherhood less negotiable than fatherhood. While the tradi-

tional nuclear family has been portrayed as a greedy organization for women

(Coser, 1974), the modern construction of motherhood does not exclude a

professional career. Still, the implicit condition seems to be that the family

should not receive less service and attention (Barnett and Baruch, 1987; Elvin-

Nowak, 1998).

As mentioned above, a number of studies show that women experience

more work–family conflict than men when spending the same time in paid

work. There are also some studies reporting similar levels of work–family

conflict among women and men (see, for example, Eagle et al., 1997;

Kinnunen and Mauno, 1998). However, research designs vary considerably

and to some extent, these inconsistencies may explain the inconsistent results.

Considering that many women adjust their behaviour (notably, their involve-

ment in paid work) precisely to avoid such a conflict, the issue of selection

effects and sampling strategies needs further attention.3 Also, it seems impor-

tant to examine whether work and family obligations have gender-specific

effects. For example, there are studies showing that income and working

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

482 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

hours have gendered effects on the amount of time spent on housework

(Brines, 1994; Greenstein, 2000; Grönlund, 2004), as well as on work–family

conflict (Gutek et al., 1991).

In this article, I examine whether job demands and job control have

gender-specific effects on work–family conflict. More precisely, I focus on

work-to-family conflict, because, increasingly, researchers recognize that

work–family conflict consists of two distinct but related concepts: work inter-

ference with family (or work-to-family conflict) and family interference with

work. However, work-to-family conflict is the most common, and the most

commonly studied, type (Allen et al., 2000; Byron, 2005; Frone, 2003; Gutek

et al., 1991).

Regarding gendered effects of job demands and job control, different

hypotheses can be formulated. On the one hand, both could have a stronger

impact among women. Because of the gendered division of housework, high

job demands may be more burdensome for a woman, while job control may

provide a way to juggle the obligations of the two spheres. However, job

control may also raise expectations that this juggling act could and should be

impeccably handled and so contribute to feelings of inadequacy and if this is

the case, control may be less positive for women (Elvin-Nowak, 1998). In

either case, gender differences are likely to be most pronounced in a situation

of high demands.

Aim, data and variables

The aim of this article is twofold. The first aim is to study the applicability of the

demand–control model to research concerning the possibility of combining

paid work and family. This will be done by analysing (a) whether job demand

increases and job control reduces the perceived level of work-to-family conflict

and (b) whether control can moderate the effect of high demands.

The second aim is to examine whether job demands and job control have

gender-specific effects on work-to-family conflict. Women’s greater responsi-

bility for housework could make job demands more of a burden and control

more of a relief. However, control may also induce feelings of personal

responsibility and guilt, especially in women, who are normatively required

to balance their work against family needs. In either case, gender differences

are likely to be most pronounced in a situation of high demands.

The sample

The article is based on Swedish data from a survey conducted by the Euro-

pean Social Survey (ESS) in 2004. The questionnaires were distributed to

representative samples of the population in different European countries. In

Sweden they were completed by 1948 individuals, or 66 per cent of those

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 483

contacted (ESS, 2004). The subsample used in this analysis consists of 800

employees who were living with a partner and/or children.

In research on work–family conflict, the possibility that women with a

strong work commitment might differ from women in general is so often

discussed that such selection is sometimes put forward as a third hypoth-

esis, beside the role strain and role expansion hypotheses (Bolger et al.,

1990). Because of this, Sweden, which is considered to be a dual breadwin-

ner society (Lewis, 1992), provides a good case to study. The labour partici-

pation and the average tenure of Swedish women are equal to those of men

and the difference in working time is only 5 hours per week (Boje and

Grönlund, 2003; SCB, 2005, 2006). While the unpaid work at home is con-

siderably more gendered, Swedish men do more housework than men in

other countries (Esping-Andersen, 1999).4 Combining multiple roles in

work and family is thus the normal situation for Swedish women and, to

some extent, for Swedish men. Consequently, selection effects should be

smaller in Sweden than elsewhere.

Measures

The dependent variable is work-to-family conflict. It is measured with an

index of four questions, asking how often the respondents (a) keep worrying

about work problems when they are not working; (b) feel too tired after work

to enjoy the things they would like to do at home; (c) find that their job

prevents them from giving the time they want to their partner or family and

(d) find that their partner or family gets fed up with the pressures of their job

(never, hardly ever, sometimes, often, always) (alpha 0.71, also see Table 1).

The concept of job demands refers to psychological stressors, primarily

related to work load and time pressure (Karasek, 1979; Karasek and Theorell,

1990). Here, the job demand index is built from two items: ‘My job requires

that I work very hard’ and ‘I never seem to have enough time to get every-

thing done in my job’ (agree strongly, agree, neither agree nor disagree,

disagree, strongly disagree) (alpha 0.53, see Table 1).

Job control is measured by an index combining three items where respon-

dents have estimated, on scales from zero to ten, the extent to which they are

allowed to (a) decide how their own daily work is organized (b) influence

policy decisions about the activities of the organization and (c) choose or

change the pace of work (alpha 0.68).

Although self-reports are commonly used to measure job demands and

control, their use is potentially problematic, especially when the dependent

variable has a subjective character. Theoretically, correlations can be overes-

timated as both dependent and independent variables may be biased by

personality factors.5 However, earlier research shows that self-reported mea-

sures of demands and, especially, control are highly correlated with expert

ratings (Karasek, 1979; Karasek and Theorell, 1990). Also, as there is no reason

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

484 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

to believe that self-report bias would affect men and women differently, the

gender patterns discussed here are not likely to be affected by validity prob-

lems (Karasek et al., 1987).

To isolate the effects of job demands and job control, I control for working

hours, class position, children and gender ideology. The primary reason is

that they may confound the relationship between job demands and job

control and work-to-family conflict. Class position may influence the levels of

job demands and control (Karasek and Theorell, 1990) and several studies

show that a higher position or income is associated with more work-to-family

conflict (see above). Therefore, if class is not controlled for, we run the risk of

attributing to job demand/control what are in fact effects of different class

positions. Similarly, respondents with demanding jobs may put in more

hours at work and since longer working hours are associated with more

work-to-family conflict, their influence should be controlled for. As noted

above, parenthood is a common indicator of demands from the home sphere.

Here, it could also be a confounder, since parents with preschool children

may choose jobs with lower demands and more control. Finally, I include

gender ideology, because people’s attitudes towards combining work and

family may influence their willingness to take a demanding job, as well as

their perceived level of work-to-family conflict.

The analyses in this article may also shed new light on results presented in

previous studies on work-to-family conflict, and this is another reason for

including variables that have been central in those studies. For example, if the

well-established effect of working hours can be attributed to job demands,

this has both practical and theoretical implications. Also, because previous

research has shown mixed results for most of these variables, it seems impor-

tant to establish their effects in this sample. As mentioned above, the risk for

selection effects should be smaller in this sample than in samples gathered

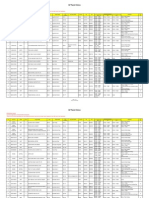

Table 1: Variable statistics

Cronbach’s

Min–max Median Mean SA alpha

Work–family conflict (n = 790) 0.00–1.00 0.37 0.39 0.17 0.71

Women (n = 389) 0.00–0.88 0.38 0.40 0.18 0.73

Men (n = 401) 0.00–1.00 0.38 0.38 0.17 0.70

Job demands (n = 799) 0.00–1.00 0.62 0.60 0.19 0.53

Women (n = 393) 0.00–1.00 0.62 0.60 0.19 0.55

Men (n = 406) 0.13–1.00 0.62 0.60 0.19 0.50

Job control (n = 788) 0.00–1.00 0.67 0.65 0.20 0.68

Women (n = 386) 0.00–1.00 0.67 0.65 0.21 0.68

Men (n = 402) 0.00–1.00 0.70 0.66 0.20 0.67

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 485

decades ago or in countries where women are less established on the labour

market.

In the analyses, the work time variable is divided in short working hours

(1–39 hours), normal full-time hours (40 hours) and long working hours (41

hours or more, which in Sweden means paid or unpaid overtime). Class

position is measured using the Goldthorpe class scheme (Erikson and

Goldthorpe, 1992). Here, five categories of employees are identified: service

classes 1 and 2, routine non-manual workers, skilled manual workers and

unskilled manual workers. In this sample, 19 per cent of the male respon-

dents, but only ten percent of the women, belong to service class 1. The

routine non-manual workers are predominantly women, while nine out of ten

skilled manual workers are men. Regarding working hours, one-fourth of the

women and almost half the men have long working hours, while 46 per cent

of the women but only 19 per cent of the men work short hours.

For parenthood, I use variables measuring whether there are preschool

children (0–6 years) and older children (7–18 years) in the home. In the latter

case, the family has at least one older but no younger child, while in the first

case there might also be older children at home. About three out of ten

respondents belong to each group. Gender ideology is an index of three

items: ‘A woman should be prepared to cut down on her paid work for the

sake of the family’, ‘Men should take as much responsibility as women for the

home and the children’ (negated) and ‘When jobs are scarce, men should have

more right to a job than women’ (agree strongly, agree, neither agree nor

disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) (alpha 0.60, higher score = more equal

attitudes). The mean value is high (0.76 on a 0–1 scale) and dispersion is low

(SD 0,14), indicating that Swedes in general have gender-equal attitudes. Also,

there is no significant difference between men and women.

Results

The first step in the analysis is to analyse how job demands and job control

influence work-to-family conflict and whether the effects are the same for

women and men. In a second step, the joint effect of demand and control will

be examined.

Work environment and family

The regression results for the total sample in Table 2 show that both job

demands and job control have the predicted effects on work-to-family con-

flict. For employees with high job demands, work spills over negatively on

private life, regardless of working hours, gender, class position and the age of

the children, while a high level of job control reduces work-to-family conflict.

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

486

Table 2: The effect of job demand, job control and control variables on work-to-family conflict. Multivariate linear regression,

B-coefficients and R2 contribution

R2 without the variable

Total sample Women Men (women–men)

Job demands 0.33*** 0.33*** 0.34*** 12.4e (13.2–15.4)

Job control -0.11*** -0.10** -0.10* 22.3e (23.0–25.9)

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Working hours (ref: 40 hours) 21.5 (20.7–24.9)

-39 hours -0.02a -0.05** 0.00

41-hours 0.05** 0.04a 0.05**

Class position (ref: unskilled manual workers) 23.2 (23.9–24.5)

Skilled manual workers 0.01 -0.01 0.01

Routine non-manual workers 0.01 0.01 -0.02

Service class 2 0.01 -0.01 0.04a

Service class 1 0.03 -0.03 0.06*

Woman (ref: man) 0.03* — — 22.9

Children (ref: no children) 22.8 (23.2–25.8)

0–6 years 0.03* 0.03 0.03a

7–18 years 0.02a 0.04* 0.00

Gender ideology 0.00 0.12* -0.10a 23.6 (23.6–25.7)

Constant 0.21*** 0.18** 0.27***

R2 as per cent (n) 23.5 (773) 24.3 (378) 26.4 (395)

T-value significant at *** 0.001 level, ** 0.01 level, * 0.05 level (a 0.10 level).

GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

© 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 487

Also long working hours are associated with more conflict and when

working hours are entered into the regression, the job demand coefficient

decreases. However, only a minor part of the effect of job demands is

explained by longer working hours. At the same time, the effect of job control

increases, indicating an interaction between control and working hours.

Further analysis shows that the conflict-reducing effect of control tends to be

lower when working hours are long, but the interaction term is only signifi-

cant at the 0.10 level. On entering class position, the effect of job control again

increases slightly, but there is no significant interaction.

Women experience more work-to-family conflict than men, even when

they are in the same class position, have children in the same age group and

put in the same number of working hours. In fact, the difference becomes

significant only when working time is controlled for. This suggests that the

length of working hours affects men and women differently, but the interac-

tion is not significant. Further, we note that parents, at least those with

preschool children, experience more conflict than non-parents, while gender

ideology has no significant effect. The coefficients of the main variables

change only negligibly when these variables are controlled for.

In sum, the effects of job demands and job control on work-to-family

remain significant when we control for working hours, class position, gender,

gender ideology and children. The coefficient for job control increases from

0.08 to 0.11 when control variables are included, but no significant interac-

tions are found. Meanwhile, the coefficient for demands decreases from 0.40

to 0.33, mainly because jobs with high demands imply longer working hours.

The results also show that some of the impact attributed to working

hours in previous research can in fact be explained by job demands. In

bivariate regressions, short working hours dampen work-to-family conflict,

but when job demands are controlled for, this effect becomes insignificant,

while the negative effect of long working hours is almost halved. Compar-

ing the variables’ contribution to R2 — the share of variance explained by

the model — we find that job demands have by far the biggest impact.

When demands are excluded, R2 drops from 23.5 to 12.4 per cent. In

comparison, the unique contribution of the other variables is marginal.

However, time and intensity are also connected, as high job demands tend

to be less problematic when working hours are short (interaction significant

at 0.052 level). In relation to previous research, it is also interesting to note

that although service class employees have a higher conflict level than

workers in bivariate regressions, this difference is explained by their higher

job demands.6

The hypotheses of gender-specific effects are not supported. As the sepa-

rate regressions in Table 2 show, job demands and job control have similar

effects for men and women. However, closer analysis reveals that the effect of

control appears at different levels for men and women. If the control index is

divided into four parts (by the quartiles) we find that men with the lowest

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

488 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

level of control experience more work-to-family conflict than other men,

while for women conflict is not reduced until their job control reaches the

highest level. The difference is confirmed by a significant interaction

(gender*control) effect at the two middle levels of control. No such gender

difference is found as regards job demands. For both men and women, the

level of conflict increases at every step, although the difference between the

middle levels is insignificant in both cases.

Regarding the other variables, we note that gender role attitudes have

gender-specific effects. Even with the same working hours and class posi-

tions, women with visions of equality experience more work-to-family con-

flict than women with traditional attitudes. The reason may be that women

who believe men should take an equal share of housework and childcare

are more frustrated by the actual, rather unequal, division of work (see

Greenstein, 1995). For men, there is an opposite tendency and interaction

terms (not presented in the Table) confirm that these gender differences are

significant. The gender differences regarding the effects of working hours

and children, however, are not. Still, the analysis suggests that part-time work

is an effective means for Swedish women to reduce work-to-family conflict.

Women with short working hours experience less conflict, despite the fact

that they do more housework than full-timers.7 Presumably, the fact that

many mothers of preschool children shift to part-time work can also explain

why only school-age children affect work-to-family conflict.

Job control as a buffer

The results presented so far are consistent with the predictions of the job

demand–control model, as high demands are more stressful than low

demands, and high control less stressful than low control. But it is now time

to investigate the joint effect of these two variables.

As noted earlier, different hypotheses can be formulated on the basis of the

demand–control model. The strain hypothesis postulates that high demands

increase stress and low control reduces it and therefore, high strain jobs

(Figure 1) are particularly stressful. The buffer hypothesis, more specifically,

claims that there is an interaction such that control moderates the negative

effect of demands. These claims will be investigated in two ways. First, the

four job types devised by Karasek and Theorell will be compared regarding

their effects on work-to-family conflict. Here, our focus is not so much on the

traditional comparison of high strain and low strain jobs, but rather on the

active job type, which is portrayed as the prototype for modern, flexible work

life (Castells, 2000; Piore and Sabel, 1984). Secondly, the interaction between

demand and control will be tested with a multiplicative interaction term. In

both cases, men and women will be compared. The general hypothesis is that

in jobs with high demands, control will have different effects for women and

men.

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 489

Table 3: Percentage of men and women with a work-to-family conflict (0.5 or more

on the conflict scale) in different job categories. The number in parentheses is the

mean value of conflict, controlling for working hours, children, class position and

gender ideology

Job demands

Low High

Job control High Low strain work Active work

Women 14.1 (0.32) Women 39.6 (0.44)

Men 12.6 (0.33) Men 43.3 (0.42)

Low Passive work High strain work

Women 2.7 (0.34) Women 53.7 (0.50)

Men 16.5 (0.33) Men 43.2 (0.45)

Table 3 displays the proportion of men and women in high strain, low

strain, passive and active jobs who experience a work-to-family conflict. To

construct the job categories the demand and control indexes were dichoto-

mized at the median value. Work–family conflict was defined as a score of 0.5

or more on the conflict scale. Since this gives a rather crude picture of the

variation and because the conflict level is also influenced by other factors, the

figure also includes the mean value of conflict, controlling for the variables

used earlier.

The table shows that most employees have either high strain or active jobs,

but that high strain jobs are more common among women than among men.

Regarding the association between job type and work-to-family conflict, we

find a sharp dividing line between jobs with high demands and those with

low demands. When demands are high, more than four out of ten respon-

dents experience work-to-family conflict; when they are low, this conflict is

only half as common. The impact of control is most obvious for women,

especially when demands are high: both the proportion of women experienc-

ing conflict and women’s average conflict level is considerably higher in high

strain jobs than in active jobs.

The impressions are confirmed by multivariate regressions (not presented

here). These show that for both women and men, low strain and passive jobs

are less stressful than high strain jobs, quite in line with the strain hypothesis.

However, the difference between high strain and active jobs is significant

only among women. This finding indicates that control could have a buffering

effect, at least for women. Also, separate regressions for the different job types

show that the gender difference in work-to-family conflict is significant only

in high strain jobs. This is another indication that when job demands are high,

control is especially important to women.

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

490 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

However, none of the interaction terms for job type and gender is signifi-

cant. Also, a multiplicative interaction term of demands and control is not

significant and neither is the three-way interaction of demand*control*gender.

In sum, the effects of job demands and job control on work-to-family conflict

appear to be additative, rather than interactive.

Discussion

The article points to a connection between individuals’ psychosocial work

environment and their capacity to strike a balance between paid work and

family life. Although no causal inferences can be made from a cross-sectional

study, the results suggest that job demands increase work-to-family conflict,

while a high degree of job control can reduce it. This indicates that Robert

Karasek’s demand–control model, which has been used for more than two

decades to study the impact of work environment on stress-related health

problems ranging from psychological distress to cardiovascular disease, is

also relevant to family research.

However, the model is not unequivocally supported. While job demands

are strongly associated with work-to-family conflict, control has a more

marginal effect. When job demands are high, they harm the balance

between the two spheres, regardless of whether control is high (as in active

jobs) or low (as in high strain jobs). Moreover, as there is no significant

interaction between demands and control, the results do not support

the idea that control can transform stressful demands into positive

challenges.

Regarding gender, there are both similarities and differences. Overall, the

effects of job demands and job control are similar among men and women,

but closer analysis shows that for women, work-to-family conflict is reduced

only when job control is at a very high level. The comparison of high strain

and active jobs also reveals some interesting gender patterns. The findings

show that active jobs are gender neutral, in the sense that women and men

experience the same work-to-family conflict, even when they have the same

working hours, class position and family situation. However, in high strain

jobs, the most common job type among women, there is a significant gender

difference in work-to-family conflict.

One reason for this finding may be that, for men, high strain jobs are

spread over a large spectrum of jobs, ranging from truck drivers to physi-

cians, while for women they are more concentrated in education, healthcare

and service positions. In the latter, the individual is highly dependent on

other people and is often confined to a certain place and schedule. As

Hochschild (2003, p. 11) pointed out, such occupations also require a substan-

tial amount of ‘emotional labour’. By contrast, active jobs are more likely to be

found in what Reich (1994, p. 155) has named the ‘symbol analytic services’,

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 491

characterized by the processing of words, figures and pictures. Such jobs can

often be performed individually and even from home, features that are likely

to facilitate handling the work–family puzzle.8

Another reason why the gender difference in conflict is eliminated when

high demands are matched by high control could be that men and women use

their job control in different ways. Women, who carry the main responsibility

at home, may use the freedom of work to balance work and family demands,

lowering their perceived conflict, while men with high control jobs may

encounter higher expectations from their partners than other men and find it

more difficult to trade off family obligations by referring to their demanding

job.

Finally, control may not only reduce strain but also produce gain —

especially for women. As shown in the article, only a high level of control

reduces work-to-family conflict for women, especially in a situation of high

demands. Jobs with that much freedom usually imply higher status and this

may facilitate the role bargaining emphasized in the expansionist view on

work-to-family conflict. In particular, a woman with an active job may face

lower expectations of traditional role enactment. Although control, as defined

in the theoretical model, does not include control over other people, this

power aspect cannot be totally dismissed.

In sum, this article shows that the issue of how the work environment

affects family life deservers further attention and research. Studies of work

and stress have put family issues aside, while research on work–family con-

flict has focused largely on working hours. However, the combination of

work and family involves more than just time. In order to reduce work–family

conflict, women resort to part-time work, but analyses of the ESS data show

that the difference in conflict between employees with high strain and low

strain jobs is the same as that between those with long hours (41 hours or

more) and those with part-time work (below 35 hours). In fact, women

working part-time in high strain jobs do not experience less conflict than

women doing 41 hours in low strain jobs. Thus, the issue of improving the

work environment is as important as the classic issue of working time when

it comes to gender and family policy.

Although job demands and job control seem to be relevant concepts, these

measures could be developed and supplemented to fit work–family research

as well. An important issue here is whether work is family flexible, that is,

whether job control means that schedules, deadlines and workload can be

temporarily adjusted to meet family needs, such as caring for a sick child.

Another issue is whether there is a corresponding control in the private

sphere, in the form of flexible gender roles, good and affordable childcare or

a network of friends and relatives, that makes it possible to temporarily

delegate caring responsibilities. Also, measures of social support at the work-

place, sometimes considered as a third dimension in the demand–control

model, could be included and extended to embrace support from the private

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

492 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

sphere. Finally, measures should be developed that capture the different

demands — for example, in emotional work — that men and women have to

meet due to the gender segregation in paid and unpaid work.

On a more general level, the findings in this article point to the importance

of further integrating work life research with research on work–family con-

flict. In the latter, different mechanisms linking the two spheres have been

thoroughly discussed, but the image of work remains poorly delineated.

Here, insights from both labour market and organizational research could

contribute to our understanding of how different aspects of work influence

work-to-family conflict.

Notes

1. Some researchers also note that even if job strain is defined as an interaction

between job demands and job control, a variety of mathematical forms can be used

to measure it (Karasek, 1979; Landsbergis et al., 1995).

2. Between 1977 and 2005 the female labour force in the USA grew by 73 per cent,

according to ILO statistics (ILO, 2005).

3. For example, a recent review shows that when a larger share of the sample

consists of parents, there are significant gender differences such that mothers

experience more work–family conflict than fathers (Byron, 2005).

4. An analysis of the ESS data used in this article also shows that Swedish men

do a significantly larger share of housework than men in other European

countries.

5. However, studies of the impact of personality on work-related stress show incon-

sistent results. It is not clear whether personality traits affect the perception of

work, whether different personalities are selected to different jobs or, indeed,

whether the work environment forms the personality (Ganster and Fusilier, 1989;

Karasek and Theorell, 1990; Landsbergis et al., 1995; Marchand et al., 2005; Spector

and O’Connell, 1994; Theorell, 2003).

6. The results also suggest that the presence of children affect work-to-family conflict

only under certain circumstances, since its effect is not significant unless variables

such as gender, job demands and job control are controlled for. This may explain

the mixed results of children in previous research. However, this sample may not

be perfect for testing the effect of children, because 69 per cent of the respondents

have children living at home.

7. A significant difference in housework between women working part-time and

those in full-time employment is found both in this sample and in several other

studies (Bianchi et al., 2000; Brines, 1994; Nordenmark, 1997).

8. These propositions are based on official Swedish statistics that show that male

high strain jobs comprise a large spectrum of occupations ranging from truck

drivers to physicians, while for women they mainly include education, healthcare

and service occupations. The same statistics show that active jobs often require a

university degree and therefore, many of them are likely to be ‘symbol analytical’

(Arbetsmiljöverket and SCB 2001).

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 493

References

Allen, Tammy D., Herst, David E.L., Bruck, Carly S. and Sutton, Martha (2000) Con-

sequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future

research, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5,2, 278–308.

Allvin, Michael (1997) Det individualiserade arbetet. Om modernitetens skilda praktiker

(The individualization of work. On the divergent practices of modernity).

Stockholm: Symposion.

Allvin, Michael and Aronsson, Gunnar (2003) The future of work environment

reforms, International Journal of Health Services, 33,1, 99–111.

Allvin, Michael, Wiklund, Per, Härenstam, Annika and Aronsson, Gunnar (1999)

Frikopplad eller frånkopplad. Om innebörder och konsekvenser av gränslösa arbeten (Free

or disconnected? About the meaning and consequences of boundaryless work).

Arbete och hälsa no. 2. Stockholm: Arbetslivsinstitutet.

Arbetsmiljöverket and SCB (2001) Negativ stress och ohälsa. Inverkan av höga krav, låg

egenkontroll och bristande socialt stöd i arbetet (Negative stress and unhealth. The

effect of high demands, low control and lack of social support at work). Informa-

tion om utbildning och arbetsmarknad 2.

Barnett, Rosalind C. and Baruch, Grace K. (1987) Social roles, gender and psychologi-

cal distress. In Barrett, R.C., Biener, L. and Baruch, G.K. Gender and Stress, pp.

122–43. New York and London: Free Press.

Beck, Ulrich (1998) Risksamhället. På väg mot en ny modernitet. Gothenburg: Daidalos.

Bianchi, Suzanne M., Milkie, Melissa A., Sayer, Liana C. and Robinson, John P. (2000)

Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor,

Social Forces, 79,1, 191–228.

Boje, Thomas P. and Grönlund, Anne (2003) Flexibility and employment insecurity. In

Boje, T.P. and Furåker, B. (eds) Post-industrial Labour Markets. Profiles of North

America and Scandinavia, pp. 186–213. London and New York: Routledge.

Bolger, Niall, DeLongis, Anita, Kessler, Ronald C. and Wethington, Elaine (1990) The

microstructure of daily role-related stress in married couples. In Eckenrode, J. and

Gore, S. (eds) Stress Between Work and Family, pp. 95–115. New York and London:

Plenum Press.

Brines, Julie (1994) Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home,

American Journal of Sociology, 100,3, 652–88.

Byron, Kristin (2005) A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its anteced-

ents, Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 67, 169–98.

Castells, Manuel (2000) Nätverkssamhällets framväxt. Informationsåldern. Ekonomi, sam-

hälle och kultur. Band 1 (The information age. economy, society and culture. Vol. 1:

the rise of the network society). Gothenburg: Daidalos.

Coser, Lewis A (1974) Greedy Institutions. Patterns of Undivided Commitment. New York:

Free Press.

Doef, Margot van der and Maes, Stan (1999) The job demand–control (–support)

model and psychological well-being: a review of 20 years of empirical research,

Work and Stress, 13,2, 87–114.

Eagle, Bruce W., Icenogle, Marjorie L., Maes, Jeanne D. and Miles, Edward W. (1997)

The importance of employee demographic profiles for understanding experiences

of work–family inter-role conflicts, Journal of Social Psychology, 138,6, 690–709.

Elvin-Nowak, Ylva (1998) Flexibilitetens baksida. Om balans, kontroll och skuld i yrkesarbet-

ande mödrars vardagsliv (The flipside of flexibility. On balance, control and guilt in

working mothers). Report no. 101, Psykologiska institutionen. Stockholm:

Stockholm University.

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

494 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

Erikson, Robert and Goldthorpe, John H. (1992) The Constant Flux. A Study of Class

Mobility in Industrial Societies. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1999) Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

European Social Survey (ESS) (2004) ESS2–2004 Documentation report. The ESS Data

Archive, Edition 1.0. Norwegian Social Science Data Services. www.europeansocial

survey.com

Fenwick, Rudy and Tausig, Mark (2001) Scheduling stress. Family and health out-

comes of shift work and schedule control, American Behavioral Scientist, 44,7, 1179–

98.

Fletcher, Ben C. and Jones, Fiona (1993) A refutation of Karasek’s demand-discretion

model of occupational stress with a range of dependent measures, Journa1 of

Occupational Behaviour, 14, 319–30.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, Karen I. and Scharlach, Andrew E. (2001) Families and Work. New

Direction s in the Twenty-First Century. New York and Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Frone, Michael R. (2003) Work–family balance. In Campbell, James Quick and Tetrick,

Lois E. (eds) Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology, pp. 143–62. Washington:

American Psychological Association.

Ganster, Daniel C. and Fusilier, Marcelline R. (1989) Control in the workplace. In

Cooper, Cary L. and Robertson, Ivan T. (eds) International Review of Industrial and

Organiztional Psychology, pp. 235–80. Chichester/New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Garhammer, Manfred (1995) Changes in working hours in Germany. The resulting

impact on everyday life, Time and Society, 4,2, 167–203.

Goode, William J. (1960) A theory of role strain, American Sociological Review, 25,4,

483–96.

Greenhaus, Jeffrey H. and Beutell, Nicholas J. (1985) Sources of conflict between work

and family roles, Academy of Management Review, 10,1, 76–88.

Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Bedeian, Arthur G. and Mossholder, Kevin W. (1987) Work

experiences, job performance and feelings of personal and family well-being,

Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 31, 200–15.

Greenstein, Theodore N. (1995) Gender ideology, marital disruption and the employ-

ment of married women, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57,1, 31–42.

Greenstein, Theodore N. (2000) Economic Dependence, gender, and the division of

labor in the home: a replication and extension, Journal of Marriage and the Family,

62,2, 322–35.

Grönlund, Anne (2004) Flexibilitetens gränser. Förändring och friktion i arbetsliv och familj

(The boundaries of flexibility. Change and friction in work and family life). Umeå:

Boréa.

Gutek, Barbara A., Searle, Sabrina and Klepa, Lilian (1991) Rational Versus gender

role expectations for work–family conflict, Journal of Applied Psychology, 74,4, 560–

68.

Hanson, Marika (2004) Det flexibla arbetets villkor — om självförvaltandets kompetens

(Self-governing competence for flexible work). Arbetsliv i omvandling no. 8. Stock-

holm: Arbetslivsinstitutet.

Härenstam, Annika and Bejerot, Eva (2001) Combining professional work with family

responsibilities — a burden or a blessing? International Journal of Social Welfare 10,3,

202–14.

Härenstam, Annika, Westberg, Hanna, Karlqvist, L., Leijon, O., Rydbeck, A., Walden-

ström, K., Wiklund, P., Nise, G. and Jansson, C. (2000) Hur kan könsskillnader i arbets-

och livsvillkor förstås? Metodologiska och strategiska aspekter samt sammanfattning av

MOA-projektets resultat ur ett könsperspektiv (How can gender differences in work

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 495

and living conditions be explained? Methodological and strategic aspects and

summary of the results from the MOA project from a gender perspective). Arbete

och hälsa 2000:15. Stockholm: Arbetslivsinstutet.

Hochschild, Arlie R. (1997) The Time Bind. When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes

Work. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Hochschild, Arlie R. (2003) The Managed Heart. Commercialization of Human Feeling,

Berkeley, Los Angeles, CA, London: University of California Press.

ILO (2005) http://laboursta.ilo.org/cgi-bin/brokerv8.exe

Karasek, Robert A. (1979) Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain,

Administrative Science Quarterly 24, June, 285–308.

Karasek, Robert A. (1989) Control in the work-place and its health related aspects. In

Sauter, Steven L, Hurrell, Joseph J. and Cooper, Cary L. (eds) (1989) Job Control and

Worker Health, pp. 29–159. Chichester and New York: John Wiley.

Karasek, Robert A. and Theorell, Töres (1990) Healthy Work. Stress, Productivity and the

Reconstruction of Working Life. New York: Basic Books.

Karasek, Robert, Gardell, Bertil and Lindell, Jan (1987) Work and non-work correlates

of illness and behaviour in male and female Swedish white collar workers, Journal

of Occupational Behaviour, 8, 187–207.

Kinnunen, Ulla and Mauno, Saija (1998) Antecedents and outcomes of work–family

conflict among employed women and men in Finland, Human Relations, 51,2,

157–77.

Landsbergis, Paul A., Schnall, Peter L., Schwatz, Joseph E., Warren, Katherine and

Pickering, Thomas G. (1995) Job strain, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease:

empirical evidence, methodological issues and recommendations for future

research. In Sauter, Steven L. and Murphy, Lawrence R. (eds.) Organizational Risk

Factors for Job Stress, pp. 97–112. Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association.

Lennon, Mary Clare and Rosenfield, Sarah (1992) Women and mental health. the

interaction of job and family conditions, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33,3,

316–27.

Lewis, Jane (1992) Gender and the development of welfare regimes, Journal of Euro-

pean Social Policy, 2,3, 159–73.

Lundberg, Ulf, Mårdberg, Bertil and Frankenhaeuser, Marianne (1994) The total

workload of male and female white collar workers as related to age, occupational

level and number of children, Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 35, 315–27.

Lundberg, Ulf and Frankenhaeuser, Marianne (1999) Stress and workload of men and

women in high-ranking positions, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4,2,

142–51.

Marchand, Alain, Demers, Andre and Durand, Pierre (2005) Do occupation and work

conditions really matter? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress among

Canadian workers, Sociology of Health and Illness, 27,5, 602–27.

Moen, Phyllis and Yu, Yan (1999) Having it all: overall work/life success in two-earner

families, Research in the Sociology of Work, 7, 109–39.

Nordenmark, Mikael (1997) Arbetslöshet, kön och familjeliv (Unemployment, gender

and family life). In Ahrne, G. and Persson, I. (eds) Familj, makt och jämställdhet

(Family, power and gender equality) SOU no. 138, pp. 293–320. Rapport till utred-

ningen om fördelningen av ekonomisk makt och ekonomiska resurser mellan

kvinnor och män Stockholm: Fritzes.

Nordenmark, Mikael (2002) Multiple social roles — a resource or a burden: is it

possible for men and women to combine paid work with family life in a satisfactory

way? Gender, Work & Organization, 9,2, 125–44.

OECD (2002) Employment Outlook. Paris: OECD.

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

496 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

Piore, Michael J. and Sabel, Charles F. (1984) The Second Industrial Divide. Possibilities

for Prosperity. New York: Basic Books.

Pitt-Catsouphes, Marcie, Kossek, Ellen Ernst and Sweet, Stephen (eds) (2006) The Work

and Family Handbook. Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives and Approaches. London:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Reich, Robert B. (1994) Arbetets marknad inför 2000-talet (The work of nations). Stock-

holm: SNS Förlag.

Sauter, Steven L., Hurrell, Joseph J. and Cooper, Cary L. (1989) Job Control and Worker

Health. Chichester and New York: John Wiley.

Statistiska Centralbyrån (SCB) (2003) Tid för vardagsliv. Kvinnors och mäns tidsanvänd-

ning 1990/91 och 2000/01 (Time for everyday life. Women’s and men’s time use

1990/91 and 2000/01). Levnadsförhållanden, report no. 99. Stockholm: SCB.

Statistiska Centralbyrån (SCB) (2005) Arbetskraftsundersökningen. Grundtabeller. Års-

medeltal (Labour force survey. Annual means). Stockholm: SCB.

Statistiska Centralbyrån (SCB) (2006) www.scb.se/templates/tableOrChart_23368.asp

Shinn, Marybeth, Wong, Nora W. Simko, Patricia A. and Ortiz-Torres, Blanca (1989)

Promoting the well-being of working parents: coping, social support and flexible

job schedules, American Journal of Community Psychology, 17,1, 31–55.

Sieber, Sam (1974) Toward a theory of role accumulation, American Sociological Review,

39,4, 567–78.

Spector, Paul E. (1998) A control theory of the job stress process. In Cooper, Cary L.

(ed) Theories of Organizational Stress, pp. 153–69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spector, Paul E. and O’Connell, Brian J. (1994) The contribution of personality traits,

negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the subsequent reports of job

stressors and job strains, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67,

1–11.

Theorell, Töres (2003) Kontroll över den egna situationen — en förutsättning för

hantering av negativ stress (Control over one’s situation — a prerequisite for

handling negative stress). In Ekman, R. and Arnetz, B. (eds) Stress — molekylerna,

individen, organisationen, samhället (Stress — molecules, individuals, organizations,

society), pp. 289–300. Stockholm: Liber.

Thoits, Peggy (1983) Multiple identities and psychological well-being: a reformulation

and test of the social isolation hypothesis, American Sociological Review, 48,2, 174–87.

Voydanoff, Patricia (1988) Work role characteristics, family structure demands and

work–family conflict, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50,3, 749–62.

Wall, Toby D., Jackson, Paul R., Mullarkey, Sean and Parker, Sharon K. (1996) The

demand–control model of job strain: a more specific test, Journal of Occupational and

Organizational Psychology, 69, 153–166.

Wallace, Jean E. (2005) Job stress, depression and work-to-family conflict. a test of the

strain and buffer hypotheses, Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 60,3, 510–39.

Warr, Peter B. (1990) Decision latitude, job demands, and employee wellbeing, Work

and Stress, 4,4, 285–94.

Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007 © 2007 The Author(s)

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

MORE CONTROL, LESS CONFLICT? 497

Appendix

Table 1: Correlations

Job demands Job control Gender Gender ideology

Job demands 1 0.006 0.004 0.078*

Job control 0.006 1 -0.058 0.006

Gender 0.004 -0.058 1 0.063

Gender ideology 0.078* 0.006 0.063 1

Correlation is significant at the * 0.05 level.

Table 2: Means in work-to-family conflict by class, gender and parenthood

Unskilled Skilled Routine non- Service Service

workers workers manual workers class 2 class 1

0.35 0.37 0.38 0.42 0.44

Men Women No children Children Children

0–6 yrs 7–18 yrs

0.38 0.40 0.38 0.40 0.40

Short working 40 hours Long working

hours (1–39) hours (41+)

0.34 0.37 0.47

© 2007 The Author(s) Volume 14 Number 5 September 2007

Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

You might also like

- Steiber2009SIR PDFDocument20 pagesSteiber2009SIR PDFAndrew FedorenkoNo ratings yet

- Dejong e 2001Document18 pagesDejong e 2001Anonymous qggLvxScNo ratings yet

- Ten Years On A Review of Recent Research On The Job Demand Control Support Model and Psychological Well BeingDocument36 pagesTen Years On A Review of Recent Research On The Job Demand Control Support Model and Psychological Well BeingAlejandro GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Wood 2016 Challenge and Hindrance StressorsDocument53 pagesWood 2016 Challenge and Hindrance Stressors王俊翰No ratings yet

- Women Executives On Work-Life Balance: An Analytical StudyDocument8 pagesWomen Executives On Work-Life Balance: An Analytical StudyAbdullah SiddiqNo ratings yet

- Rudolph Et Al-2015-Stress and HealthDocument14 pagesRudolph Et Al-2015-Stress and HealthMonica PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Work Adjustment Theory: An Empirical Test Using A Fuzzy Rating ScaleDocument21 pagesWork Adjustment Theory: An Empirical Test Using A Fuzzy Rating ScalePhạm LinhNo ratings yet

- Job Stress and Job Performance Controversy: An Empirical AssessmentDocument21 pagesJob Stress and Job Performance Controversy: An Empirical AssessmentArun MaxwellNo ratings yet

- JNM - 2013 - Analyzing Work Alienation and Its Effects - FINALDocument21 pagesJNM - 2013 - Analyzing Work Alienation and Its Effects - FINALhasnat basirNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Selected Psycho Graphic Variables On Individual Job StressDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Selected Psycho Graphic Variables On Individual Job Stressabi12No ratings yet

- 1.IJHRM - Occupational - Pia Muriel CardosoDocument8 pages1.IJHRM - Occupational - Pia Muriel Cardosoiaset123No ratings yet

- 8 Aminah Ahmad1 PDFDocument9 pages8 Aminah Ahmad1 PDFMas Roy TambbachEleggNo ratings yet

- 24 Hour Banking Deal or Dilemma - AIMS 2006 - IIM AhmadabadDocument7 pages24 Hour Banking Deal or Dilemma - AIMS 2006 - IIM AhmadabadVikram VenkateswaranNo ratings yet

- Rollero, Fedi, de Piccoli, 2016 SIRDocument32 pagesRollero, Fedi, de Piccoli, 2016 SIRTehmina QaziNo ratings yet

- Stress Is Not Always Negative or Harmful and IndeedDocument3 pagesStress Is Not Always Negative or Harmful and Indeedsalm owaiNo ratings yet

- Consecinte Ale CMF Asupra Starii de BineDocument13 pagesConsecinte Ale CMF Asupra Starii de BineAndra Corina CraiuNo ratings yet

- Relationships of Work - Family Conflict With Business and Marriage Outcomes in Taiwanese Copreneurial WomenDocument13 pagesRelationships of Work - Family Conflict With Business and Marriage Outcomes in Taiwanese Copreneurial WomenKamboj BhartiNo ratings yet

- Three Work Stress Models and Psychological Well-Beings of EmployeesDocument18 pagesThree Work Stress Models and Psychological Well-Beings of EmployeesPisitta Nurse VongswasdiNo ratings yet

- Attribution Theory and Self EfficacyDocument14 pagesAttribution Theory and Self EfficacyJithesh Kumar KNo ratings yet

- Article 3Document30 pagesArticle 3danstane11No ratings yet

- Organizational Psychology Review 2012 Gutnick 189 207Document19 pagesOrganizational Psychology Review 2012 Gutnick 189 207Nela BellovodaNo ratings yet

- Reviewing The Effort-Reward Imbalance Model:drawing Up The Balance of 45 Empirical StudiesDocument15 pagesReviewing The Effort-Reward Imbalance Model:drawing Up The Balance of 45 Empirical StudiesPandu Fatwa AnugrahNo ratings yet

- McClelland's Acquired Needs TheoryDocument14 pagesMcClelland's Acquired Needs TheorySuman SahaNo ratings yet

- Affectivity, Organizational Stressors, and Absenteeism: A Causal Model of Burnout and Its ConsequencesDocument23 pagesAffectivity, Organizational Stressors, and Absenteeism: A Causal Model of Burnout and Its ConsequencesalberNo ratings yet

- Anchal Kumar - A Study On Work Life Balance in Hospitality IndustryDocument40 pagesAnchal Kumar - A Study On Work Life Balance in Hospitality Industryvipul guptaNo ratings yet

- The Curvilinear Relation Between Experienced Creative Time Pressure and Creativity: Moderating Effects of Openness To Experience and Support For CreativityDocument8 pagesThe Curvilinear Relation Between Experienced Creative Time Pressure and Creativity: Moderating Effects of Openness To Experience and Support For CreativityalexandrasecretariaNo ratings yet

- Toward A Dual-Process Model of Work-Home InterferenceDocument22 pagesToward A Dual-Process Model of Work-Home InterferenceBeaHmNo ratings yet

- Weom 050093 ProofsDocument6 pagesWeom 050093 Proofsjomel rodrigoNo ratings yet

- Real Time Affect at Work: A Neglected Phenomenon in Organisational BehaviourDocument10 pagesReal Time Affect at Work: A Neglected Phenomenon in Organisational BehaviourCRNIPASNo ratings yet

- Southeast Asia Psychology JournalDocument12 pagesSoutheast Asia Psychology Journalyufei78No ratings yet

- Juggle Between Work HOME IN UK WOMENDocument50 pagesJuggle Between Work HOME IN UK WOMENANKIT SINGH RAWATNo ratings yet

- A Longitudinal and Multi-Source Test of The Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction RelationshipDocument20 pagesA Longitudinal and Multi-Source Test of The Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction RelationshipkobieroNo ratings yet

- J Hannes 2011Document14 pagesJ Hannes 2011agusSanz13No ratings yet

- BalanceDocument28 pagesBalancetaliabelal2017No ratings yet

- Academy of ManagementDocument31 pagesAcademy of ManagementPascia SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Workfamily BalanceDocument21 pagesWorkfamily Balanceshankar_missionNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Occupational StressDocument8 pagesThesis On Occupational Stressnicolesavoielafayette100% (2)

- ISSN 1466-1535: SKOPE Research Paper No. 84 May 2009Document34 pagesISSN 1466-1535: SKOPE Research Paper No. 84 May 2009Tanvee SharmaNo ratings yet

- Theeffectsofthephysical Environmentonjob Performance:towards Atheoreticalmodel OfworkspacestressDocument10 pagesTheeffectsofthephysical Environmentonjob Performance:towards Atheoreticalmodel OfworkspacestressHaris Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Wilson Baumann Matta Ilies Kossek 2018 AMJDocument23 pagesWilson Baumann Matta Ilies Kossek 2018 AMJPetrutaNo ratings yet

- Sample 2Document14 pagesSample 2David KariukiNo ratings yet

- JOB 2002 Van Dyne Jehn Cummings Work StrainDocument18 pagesJOB 2002 Van Dyne Jehn Cummings Work StrainAbdalur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Albardilla2020Revista de Estudios de La FelicidadDocument21 pagesAlbardilla2020Revista de Estudios de La FelicidadMaria Angelica Alferez AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Review of Literature Work Life BalanceDocument6 pagesReview of Literature Work Life BalancetusharNo ratings yet

- Balancing Work and Home How Job and HomeDocument19 pagesBalancing Work and Home How Job and HomeIulia NicoriciNo ratings yet

- Working To Live or Living To Work Worklife Balance Early in The CareerDocument20 pagesWorking To Live or Living To Work Worklife Balance Early in The Careerapi-245973900100% (1)

- The Impact of Demoggraphic Factors On Family Interference With Work and Work Interference With Family and Life SatisfactionDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Demoggraphic Factors On Family Interference With Work and Work Interference With Family and Life SatisfactioninventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Making The Link Between Work Life Balance Practices and Organizational Performance (LSERO Version)Document52 pagesMaking The Link Between Work Life Balance Practices and Organizational Performance (LSERO Version)NoorunnishaNo ratings yet

- Work Life Balance and Well Being-1Document21 pagesWork Life Balance and Well Being-1Expert WritersNo ratings yet

- Michael ArgyleDocument13 pagesMichael Argylepeye28No ratings yet

- THEORY Used To Explain ProjectDocument3 pagesTHEORY Used To Explain ProjectLaiba khanNo ratings yet

- Predicting Occupational Coping Responses - Journal of Occupational Health PsychologyDocument10 pagesPredicting Occupational Coping Responses - Journal of Occupational Health PsychologyDavid W. AndersonNo ratings yet

- Managing Occupational Stress in A High-Risk Industry Measuring The Job Demands of Correctional OfficersDocument13 pagesManaging Occupational Stress in A High-Risk Industry Measuring The Job Demands of Correctional OfficersNorberth Ioan OkrosNo ratings yet

- When Less Time Is Preferred. An Analysis of The Conceptualization and Measurement of OveremploymentDocument29 pagesWhen Less Time Is Preferred. An Analysis of The Conceptualization and Measurement of OveremploymentCarlos SáezNo ratings yet

- EdwardsRothbard1999 PDFDocument45 pagesEdwardsRothbard1999 PDFAngelica HalmajanNo ratings yet

- Stress in OrganisationsDocument40 pagesStress in OrganisationsVatsala MirnaaliniNo ratings yet

- نموذج الحفاظ على الموارد المطبق على العمل - الصراع والتوتر الأسريDocument22 pagesنموذج الحفاظ على الموارد المطبق على العمل - الصراع والتوتر الأسريkhalid alkhudhirNo ratings yet

- A Role For Equity Theory in The TurnoverDocument21 pagesA Role For Equity Theory in The TurnoverSinh TruongNo ratings yet

- Spillover PDFDocument22 pagesSpillover PDFmiudorinaNo ratings yet

- SOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTFrom EverandSOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTNo ratings yet

- ID Perbedaan Gaya Kepemimpinan Dalam PerspeDocument10 pagesID Perbedaan Gaya Kepemimpinan Dalam PerspeFery ApriadiNo ratings yet

- Using Social Enterprises For Social Policy in South Korea - Kim - 2017Document14 pagesUsing Social Enterprises For Social Policy in South Korea - Kim - 2017putrifaNo ratings yet

- Prodi Manajemen: e - Jurnal Riset Manajemen Fakultas Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Unisma WebsiteDocument10 pagesProdi Manajemen: e - Jurnal Riset Manajemen Fakultas Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Unisma WebsiteputrifaNo ratings yet

- 109 75615 1 10 20180221Document32 pages109 75615 1 10 20180221putrifaNo ratings yet

- Business-Unit-Level Relationship Between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesBusiness-Unit-Level Relationship Between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-AnalysisputrifaNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Brand Awarenes, Brand Acosiation Dan Perceived Quality Terhadap Keputusan Pembelian PC Tablet Di Kota PadangDocument23 pagesPengaruh Brand Awarenes, Brand Acosiation Dan Perceived Quality Terhadap Keputusan Pembelian PC Tablet Di Kota PadangputrifaNo ratings yet