Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sabbe Sa Khārā Aniccā Iti Yadā Paññāya Passati

Uploaded by

Archon Rehabh0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views1 pageOriginal Title

Content (1)_Part45

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views1 pageSabbe Sa Khārā Aniccā Iti Yadā Paññāya Passati

Uploaded by

Archon RehabhCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

ideas that we associate with “our eternal selves”.

But our permanent self is a myth,

and once we learn that, we can look beyond the need to have life stay the same.

First of all, aniccā refers to everything in this world which is impermanent.

The characteristic of impermanence has been noted not only in Buddhist thought but

also elsewhere in the history of thought. It was the ancient Greek philosopher

Heraclitus who observed that one cannot step down the same river twice.

In the Buddhist scriptures it is said that everything is impermanent like clouds,

samsara like dancing, human beings like lightning or falls. Similarly, our mental

states are impermanent. At one point we were happy, and at another we were sad.

This is true also of things we see around us. Understanding impermanence is

important not only simply for our practice of the Dhamma but also in our daily lives.

It is a key to understanding the ultimate nature of things.

Impermanent indeed are the compounded things, they are of the nature of

arising and passing away. Having come into being, they cease to exist. Hence their

pacification is tranquility. Impermanence is a synonym for “arising and passing

away” or “birth and destruction”. In fact, the law of universal impermanence has not

only negative or destructive aspect but also a positive or constructive one. It is on the

truth of the impermanence of the nature that the possibility of all things depends. If

things do not change continuously but are permanent and irreversible, then human

evolution and the development of lives will come to a dead stop.

But due to perversion of view, one is unable to see the true nature of existent

reality. One sees things which are impermanent as permanent and becomes

passionately attached to those things which are transient, mutable and therefore

unsatisfactory. The Buddha has said that, “Yad aniccaṃtaṃdukkham”. It means that

whatever is impermanent is unsatisfactory. The world dukkha is rendered variously as

“ill”, “suffering”, “pain” or “unsatisfactoriness”. We do not deny that there are

different forms of happiness, both physical and spiritual, for layperson as well as for

the monastic. But all these are included as Dukkha, not because there is suffering in

the ordinary sense of the word, but because “Anything is impermanent in dukkha”.

The Dhammapāda says:

Sabbe saṅkhārā aniccā iti yadā paññāya passati

45

You might also like

- Mythological Body~ A New Age Physiology Philosophy [Sharirvigyan Darshan]From EverandMythological Body~ A New Age Physiology Philosophy [Sharirvigyan Darshan]No ratings yet

- Grief and Counseling NotesDocument4 pagesGrief and Counseling NotesWonjiDharmaNo ratings yet

- The Vedic Description of The SoulDocument4 pagesThe Vedic Description of The SoulBraham sharmaNo ratings yet

- Bascis Hare Rama Hare KrishnaDocument70 pagesBascis Hare Rama Hare KrishnaRahul GautamNo ratings yet

- Module 2: Swami Vivekananda Section 2: Nature of ManDocument4 pagesModule 2: Swami Vivekananda Section 2: Nature of ManAbhijeet JhaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Buddhism - Rewata Dhamma SayadawDocument23 pagesIntroduction To Buddhism - Rewata Dhamma SayadawDhamma ThoughtNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Concept of RebirthDocument22 pagesBuddhist Concept of RebirthDhammaland IndiaNo ratings yet

- Blossoms Fall Booklet Edition3 PrintfinalDocument22 pagesBlossoms Fall Booklet Edition3 PrintfinalNancyLeeNo ratings yet

- The Lha or Energy BodyDocument4 pagesThe Lha or Energy BodyMichael Erlewine100% (1)

- Metaphysics - Upanishads EssenceDocument59 pagesMetaphysics - Upanishads EssencebantysethNo ratings yet

- BondageDocument7 pagesBondageEdilbert ConcordiaNo ratings yet

- Breath of LifeDocument217 pagesBreath of LifeAnonymous VJYMo8l89Y100% (2)

- Emptiness Meditation in Kalachakra Practice Dr. Alexander BerzinDocument15 pagesEmptiness Meditation in Kalachakra Practice Dr. Alexander BerzinErcan CanNo ratings yet

- Nibbana by Bhikkhu Bodhi PDFDocument4 pagesNibbana by Bhikkhu Bodhi PDFhaykarmelaNo ratings yet

- Into The Dharma Verse HandoutDocument3 pagesInto The Dharma Verse HandoutSabaoth777No ratings yet

- Śańkar's Concept About T He "Nature of Self": Sandhya NandyDocument8 pagesŚańkar's Concept About T He "Nature of Self": Sandhya Nandyeeyas MachiNo ratings yet

- The Dalai Lama On Death and DyingDocument3 pagesThe Dalai Lama On Death and DyingJohn LewisNo ratings yet

- Abhidhamma and PracticeDocument18 pagesAbhidhamma and PracticeRick Thornbrugh100% (1)

- Navigating The Bardos by Roger J. WoolgerDocument15 pagesNavigating The Bardos by Roger J. Woolgerbrisamaritima56No ratings yet

- On of Soul in Gita WayDocument15 pagesOn of Soul in Gita WayAkshay JadavNo ratings yet

- Yearning of The SoulDocument97 pagesYearning of The SoulViraj PanaraNo ratings yet

- Answers About The AfterlifeDocument13 pagesAnswers About The AfterlifeRitesh Verma100% (1)

- State of AlonenessDocument8 pagesState of AlonenessErendiraNo ratings yet

- Brahm AcharyaDocument4 pagesBrahm AcharyaBr Bao TichNo ratings yet

- BrahmacharyaDocument4 pagesBrahmacharyaPreetam MondalNo ratings yet

- Swami Nirmalananda Giri - The Breath of LifeDocument217 pagesSwami Nirmalananda Giri - The Breath of LifePaola DiazNo ratings yet

- Wholesome Fear: Transforming Your Anxiety About Impermanence and DeathFrom EverandWholesome Fear: Transforming Your Anxiety About Impermanence and DeathRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Annatta, Annica, and Dukkha Power PointDocument10 pagesAnnatta, Annica, and Dukkha Power PointStephen LeachNo ratings yet

- Rebirth and KammaDocument91 pagesRebirth and KammasatiNo ratings yet

- Buddhism View On DeathDocument3 pagesBuddhism View On DeathTanya Alyssa Untalan AquinoNo ratings yet

- Nibbana by Bhikkhu BodhiDocument4 pagesNibbana by Bhikkhu Bodhianjana12No ratings yet

- Doc101 222 p2 TextDocument69 pagesDoc101 222 p2 TextjhapraveshNo ratings yet

- The Dhammapada for Awakening: A Commentary on Buddha's Practical WisdomFrom EverandThe Dhammapada for Awakening: A Commentary on Buddha's Practical WisdomRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Understanding Reality - Nina Van GorkomDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Reality - Nina Van Gorkom5KevNo ratings yet

- Simply Being - A CommentaryDocument5 pagesSimply Being - A CommentaryDr Edo ShoninNo ratings yet

- I. Introduction To Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma, and SanghaDocument4 pagesI. Introduction To Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma, and SanghaLuiz AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Kundalini Awakening and Altered States by Sound - 2012Document7 pagesKundalini Awakening and Altered States by Sound - 2012James ShivadasNo ratings yet

- Self Enquiry - The Method and Its Fruit - Eng & Port - 16 PgsDocument14 pagesSelf Enquiry - The Method and Its Fruit - Eng & Port - 16 PgsJoão Rocha de LimaNo ratings yet

- Stages On The PathDocument8 pagesStages On The PatharpitaNo ratings yet

- Ritual Meditations - TendaiDocument8 pagesRitual Meditations - TendaiMonge Dorj75% (4)

- Thezensite - Lecture On Dogen Zenji's Genjo-Koan by Okumura - enDocument32 pagesThezensite - Lecture On Dogen Zenji's Genjo-Koan by Okumura - enzdenek.bernardNo ratings yet

- Yearning of The SoulDocument26 pagesYearning of The SoulAnonymous AHIfjTqLFlNo ratings yet

- The Dhammapada for Awakening: A Commentary on Buddha's Practical WisdomFrom EverandThe Dhammapada for Awakening: A Commentary on Buddha's Practical WisdomNo ratings yet

- Birth and DeathDocument6 pagesBirth and DeathNyi SherNo ratings yet

- Julius Evola - The Meaning and Context of ZenDocument4 pagesJulius Evola - The Meaning and Context of Zenrichardrudgley100% (1)

- Dying and Death EbookDocument56 pagesDying and Death Ebooklivsnervo100% (1)

- Dona HollemanDocument5 pagesDona Hollemanstefanobendandi7550% (2)

- Life does not end here: Itinerary of Metapsychic PhilosophyFrom EverandLife does not end here: Itinerary of Metapsychic PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- GOD in us. The Spirit in the body. Essay on the Survival of Perception.: Itinerary of Metapsychic PhilosophyFrom EverandGOD in us. The Spirit in the body. Essay on the Survival of Perception.: Itinerary of Metapsychic PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- THE TWO KINDS OF REALITY Sayadaw U JotikaDocument15 pagesTHE TWO KINDS OF REALITY Sayadaw U JotikaPollts100% (1)

- Your BodyDocument14 pagesYour BodyWilliam AllenNo ratings yet

- Samadhi 2Document6 pagesSamadhi 2Genevieve BegueNo ratings yet

- Born Together With All BeingsDocument6 pagesBorn Together With All BeingsDannyPasenadiNo ratings yet

- The Unsolved Mystery of Life and Death: 蛻變:生命存在與昇華的實相(國際英文版:卷一)From EverandThe Unsolved Mystery of Life and Death: 蛻變:生命存在與昇華的實相(國際英文版:卷一)No ratings yet

- Some Worksheets Sent by Schools Showing Utilization of Printer and Worksheets Donated For Special ChildrenDocument1 pageSome Worksheets Sent by Schools Showing Utilization of Printer and Worksheets Donated For Special ChildrenArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- 50 Worksheets Specially Designed For Children With Special Needs, An Example Is Shown AboveDocument1 page50 Worksheets Specially Designed For Children With Special Needs, An Example Is Shown AboveArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Name of Special Software:-PARTS OF THE BODYDocument1 pageName of Special Software:-PARTS OF THE BODYArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Name of Special Software:-THE ELEPHANT'S STORYDocument1 pageName of Special Software:-THE ELEPHANT'S STORYArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Smart FdsiDocument1 pageSmart FdsiArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Smart FdsiDocument1 pageSmart FdsiArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Smart FdsiDocument1 pageSmart FdsiArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- 2017 18 3Document1 page2017 18 3Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- M IEWS Annual Report 2010-11Document64 pagesM IEWS Annual Report 2010-11Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Report On Project Smart - Fdsi A CSR Initiative of Fourth Dimension Solutions LTDDocument1 pageReport On Project Smart - Fdsi A CSR Initiative of Fourth Dimension Solutions LTDArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Highlights of The Year 2017-18: Worksheets Were Developed For CWSN ChildrenDocument1 pageHighlights of The Year 2017-18: Worksheets Were Developed For CWSN ChildrenArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Iews 2017Document1 pageIews 2017Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- M IEWS Annual Report 2009-10Document26 pagesM IEWS Annual Report 2009-10Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Year 2016-2017Document1 pageOverview of The Year 2016-2017Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Or Play Ing Movies, Presentatio NsDocument1 pageOr Play Ing Movies, Presentatio NsArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2017-18: August 3Document1 pageAnnual Report 2017-18: August 3Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Assisted Rehab Care Home For Nurturing (Archon)Document1 pageAssisted Rehab Care Home For Nurturing (Archon)Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

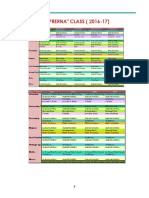

- Yearly Report "PRERNA" CLASS (2016-17)Document1 pageYearly Report "PRERNA" CLASS (2016-17)Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- 2017-18-19Document1 page2017-18-19Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Progress in 2017-18:: Medicines and Tonics Added This YearDocument1 pageProgress in 2017-18:: Medicines and Tonics Added This YearArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Resource Center PartnershipDocument1 pageResource Center PartnershipArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Prerna - Resource Center in St. Thomas SchoolDocument1 pagePrerna - Resource Center in St. Thomas SchoolArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- 2017 18 3Document1 page2017 18 3Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- 2017-18-19Document1 page2017-18-19Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Resource Center PartnershipDocument1 pageResource Center PartnershipArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Assisted Rehab Care Home For Nurturing (Archon)Document1 pageAssisted Rehab Care Home For Nurturing (Archon)Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Enefits of Educational Software For Children With Special Needs, Developed by Project SMARTDocument1 pageEnefits of Educational Software For Children With Special Needs, Developed by Project SMARTArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2017-18: August 3Document1 pageAnnual Report 2017-18: August 3Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Year 2016-2017Document1 pageOverview of The Year 2016-2017Archon RehabhNo ratings yet

- Enefits of Educational Software For Children With Special Needs, Developed by Project SMARTDocument1 pageEnefits of Educational Software For Children With Special Needs, Developed by Project SMARTArchon RehabhNo ratings yet

![Mythological Body~ A New Age Physiology Philosophy [Sharirvigyan Darshan]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/709216737/149x198/a930ce142e/1709964282?v=1)