Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anthrax Infection Among Heroin

Anthrax Infection Among Heroin

Uploaded by

Asmi AsmuCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anthrax Infection Among Heroin

Anthrax Infection Among Heroin

Uploaded by

Asmi AsmuCopyright:

Available Formats

BRIEF REPORT

METHODS

Anthrax Infection Among Heroin

Users in Scotland During 2009– The Scottish Drugs Misuse Database (SDMD) holds informa-

2010: A Case-Control Study by tion on individuals attending treatment services for problem

drug use (first visit or first visit in 6 months) [4], capturing

Linkage to a National Drug information from specialist drug services and general practi-

Treatment Database tioners across Scotland. Using data collated by Health Protec-

tion Scotland during the anthrax outbreak investigation, 82

Norah E. Palmateer,1 Colin N. Ramsay,2 Lynda Browning,3 confirmed/probable cases of anthrax were probabilistically

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/55/5/706/351765 by guest on 30 March 2021

David J. Goldberg,1 and Sharon J. Hutchinson1,4 linked to the SDMD (data available to 31 March 2010) using

1

Blood-Borne Viruses and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2Environmental Public the limited identifiers available (first and fourth characters of

Health, and 3Gastrointestinal Disease and Zoonoses, Health Protection Scotland, surname, first part postcode, sex, and date of birth). Data from

and 4Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Strathclyde,

Glasgow, United Kingdom each linked case’s last SDMD registration were extracted. Ten

controls per linked case were randomly selected from the

SDMD and were matched to cases by attendance at the same

Using a data-linkage approach, we conducted a case-control

study to investigate risk factors in an outbreak of anthrax or nearby drug treatment service within a period of ± 12

infection among Scottish heroin users. Factors associated months. Controls were restricted to individuals who had re-

with an increased risk of infection included longer injecting ported using heroin in the month prior to registration.

history, receiving opioid substitution therapy, and alcohol Conditional (matched) logistic regression analyses were

consumption. Smoking heroin was associated with lower conducted to examine the association between potential risk

risk of infection. factors, derived from the SDMD data, and case/control status.

Variables with P values <.1 (based on the univariable associa-

tion) were considered for inclusion in multivariable models.

During December 2009–October 2010, 82 confirmed/probable Two multivariable models were fitted, examining the entire

cases of infection with Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) were de- sample and those who had reported ever injecting (according

tected across Scotland among drug using individuals [1, 2]. All to their SDMD registration).

cases reported injecting and/or smoking heroin during the Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the robust-

week prior to onset of illness [2]. Most cases presented with ness of the multivariable models to the exclusion of the fol-

severe soft tissue infections, with the more seriously ill patients lowing cases (and corresponding controls): 3 cases with

having symptoms consistent with systemic infection. The pre- SDMD registration dates after anthrax onset, 14 cases with ≥5

sentations were generally not typical of classical cutaneous or years between registration and anthrax onset, and 9 cases who

pulmonary anthrax [2]: a previously documented case in had not reported taking heroin in the month prior to their

Norway of anthrax in an injector [3] led the investigators to last registration. All analyses were undertaken in Stata version

propose the term “injectional” anthrax. 9.2 software.

To determine the demographic/behavioral correlates of

anthrax infection, we conducted a case-control analysis of data

obtained via linkage of the Scottish anthrax cases to a national RESULTS

drug treatment database.

Sixty-five of 82 (79%) cases linked to the SDMD. A compari-

son of individuals who did and did not link to the SDMD

Received 10 February 2012; accepted 14 May 2012; electronically published 22 May 2012. revealed that a significantly larger proportion of nonlinkers

Correspondence: Norah Palmateer, BScH, MSc, Meridian Court, 4th Fl, 5 Cadogan St,

Glasgow, G2 6QE, United Kingdom (norah.palmateer@nhs.net).

lived in the west of Scotland (88% vs 62%, P = .03). Gender of

Clinical Infectious Diseases 2012;55(5):706–10 linkers and nonlinkers was identical (71% male). Linkers were

© The Author 2012. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Infectious Diseases slightly older than nonlinkers (mean age 35.2 vs 32.6, median

Society of America. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please e-mail: journals.

permissions@oup.com.

age 36 vs 31, respectively), although this was not statistically

DOI: 10.1093/cid/cis511 significant.

706 • CID 2012:55 (1 September) • BRIEF REPORT

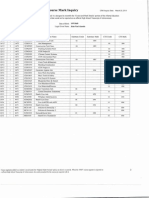

Table 1. Comparison of Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics Between Scottish Anthrax Cases (n = 65) and Controls (n = 650)

Unadjusted Conditional Logistic

Cases Controls Regression

Characteristic N % N % OR 95% CI P Value

Gender

Male 46 71 458 70 1.00

Female 19 29 192 30 0.98 .56–1.74 .96

Age at last attendance (years)

<25 12 18 147 23 1.00 … …

25–29 15 23 169 26 1.12 .50–2.53 .78

30–34 13 20 155 24 1.08 .47–2.50 .86

35+ 25 38 179 28 1.84 .85–3.98 .12

Time since onset of drug use (107

missing)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/55/5/706/351765 by guest on 30 March 2021

<9 years 11 21 154 28 1.00 … …

9–15 years 20 38 180 32 1.48 .67–3.26 .25

16+ years 21 40 222 40 1.17 .52–2.64 .70

Time since onset of problematic drug

use (82 missing)

<5 years 14 25 174 30 1.00 … …

5–9 years 11 20 187 32 0.71 .31–1.63 .42

10+ years 31 55 216 37 1.78 .88–3.61 .11

Ever injected (10 missing)

No 8 12 163 25 1.00 … …

Yes 57 88 477 75 2.67 1.21–5.87 .02

Injected in past month (72 missing)

No 21 36 257 44 1.00 … …

Yes 37 64 328 56 1.50 .83–2.71 .18

Time since onset of injecting, among

those who had ever injected (67

missing)

<5 years 18 35 174 41 1.00 … …

5–9 years 6 12 110 26 0.50 .19–1.33 .16

10+ years 27 53 142 33 2.00 1.00–3.97 .05

Shared needle/syringe in past month,a

among those who had injected in past

month (118 missing)

No 25 78 228 79 1.00 … …

Yes 7 22 59 21 1.36 .50–3.69 .55

Shared other injecting equipment in past

monthb, among those who had

injected in past month (142 missing)

No 22 69 175 67 1.00 … …

Yes 10 31 88 33 0.97 .41–2.27 .94

Route of heroin administration in past

monthc,d (4 missing)

Injecting, but not smokinge 28 50 242 37 1.00 … …

Injecting and smokinge 10 18 98 15 0.95 .43–2.12 .90

Smoking, but not injectinge 16 29 298 46 0.47 .24–.92 .03

Other only 2 4 8 1 2.64 .40–17.45 .32

Frequency of heroin taking in past

monthc (51 missing)

<daily 11 20 113 19 1.00 … …

≥daily 43 80 488 81 0.72 .34–1.50 .38

BRIEF REPORT • CID 2012:55 (1 September) • 707

Table 1 continued.

Unadjusted Conditional Logistic

Cases Controls Regression

Characteristic N % N % OR 95% CI P Value

Heroin quantity in a typical day during

past monthc (450 missing)

<0.5 g 10 53 107 45 1.00

≥0.5 g 9 47 130 55 0.77 .29–2.02 .60

Currently receiving any prescription

drugsf (149 missing)

Any OST ± other drug 25 48 153 30 1.00 … …

Other drug only 1 2 48 9 0.09 .01–.79 .03

None 26 50 313 61 0.41 .21–.79 .01

Ever tested for hepatitis C (288 missing)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/55/5/706/351765 by guest on 30 March 2021

No 13 31 159 41 1.00 … …

Yes 29 69 226 59 1.53 .77–3.05 .22

Any alcohol consumption in past month

(234 missing)

No 24 55 300 69 1.00 … …

Yes 20 45 137 31 1.88 .98–3.62 .06

Excessive alcohol consumption in past

monthg (275 missing)

No 28 82 355 87 1.00 … …

Yes 6 18 51 13 1.61 .61–4.20 .34

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; OST, opioid substitution therapy.

a

Sharing may include borrowing or lending used needles/syringes.

b

Other equipment includes spoons, filters, or water.

c

Among those who reported taking heroin in the last month (56 of 65 cases, and all controls).

d

Injecting includes intravenous or intramuscular injecting; smoking includes snorting and inhalation; “other” includes routes of administration reported as

swallowing, oral, or other.

e

These categories may also include those who take heroin via the “other” route, as defined above.

f

Other drug refers to any prescription drug other than opioid substitutes (eg, antidepressants, sedatives, etc).

g

Excessive defined as >14 units/week for women and >21 units/week for men.

Table 1 presents the unadjusted analyses of demographic/ generated using the whole sample, with the exception of

behavioral characteristics of cases and controls. Ever injecting, smoking heroin, which was no longer significantly associated

time since onset of injecting, route of heroin administration, with case status (AOR, 0.57; 95% CI, .28–1.15, P = .12).

receiving opioid substitution therapy (OST), and alcohol con- The models generated from sensitivity analyses were very

sumption were significantly associated with case/control similar to that generated using all cases (not shown; available

status. from authors on request).

In adjusted analyses, among all subjects, those who had

been injecting for ≥10 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 2.43; DISCUSSION

95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31–4.52) and those who were

currently receiving OST (AOR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.40–5.37) were By using a record-linkage approach to generate case-control

both more likely to be a case (Table 2). Individuals who only data [5], we have identified selected risk factors for anthrax

smoked heroin in the past month were less likely to be a case infection in the recent Scottish outbreak. This approach was

(AOR, 0.42; 95% CI, .20–.86). Alcohol consumption in the used because it was not possible to undertake a traditional

past month was marginally associated (P = .09) with greater case-control study due to logistic constraints, and because the

odds of being a case (AOR, 1.77; 95% CI, .91–3.47). When information collected during the anthrax outbreak investiga-

analyses were restricted to those who had ever injected tion did not have controls for comparison. We found that

(Table 2), the effect sizes and P values were similar to those longer injecting history, receiving OST, and alcohol

708 • CID 2012:55 (1 September) • BRIEF REPORT

Table 2. Multivariable Conditional (Matched) Logistic Regression Analyses on (a) All Anthrax Cases and Controls, and (b) Anthrax

Cases and Controls Who Reported Having Ever Injected Drugs on Their Last Scottish Drugs Misuse Database Registration

b) Subjects Who Reported Ever Injecting Drugs

a) All Subjects (N = 715) (N = 488)

Adjusted Conditional Adjusted Conditional

Cases Controls Logistic Model Cases Controls Logistic Model

Characteristic N % N % AOR 95% CI P Value N % N % AOR 95% CI P Value

Time since onset of injecting

<10 years 24 37 284 44 1.00 … … 24 42 257 60 1.00 … …

10+ years 27 42 142 22 2.43 1.31–4.52 <.01 27 47 128 30 2.49 1.33–4.67 <.01

Never injected 8 12 163 25 1.02 .37–2.83 .96 … … … … … … …

Missing 6 9 61 9 1.08 .38–3.03 .89 6 11 46 11 1.13 .39–3.32 .82

Route of heroin administration—

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/55/5/706/351765 by guest on 30 March 2021

only smoked heroin in past

montha

No 49 75 352 54 1.00 … … 45 79 300 70 1.00 … …

Yes 16 25 298 46 0.42 .20–.86 .02 12 21 131 30 0.57 .28–1.15 .12

Currently receiving OST

No 27 42 361 56 1.00 … … 24 42 239 56 1.00 … …

Yes 25 38 153 24 2.74 1.40–5.37 <.01 23 40 118 27 2.44 1.16–5.14 .02

Missing 13 20 136 21 1.42 .60–3.35 .42 10 18 74 17 1.56 .63–3.91 .34

Any alcohol consumption in past

month

No 24 37 300 46 1.00 … … 20 35 207 48 1.00 … …

Yes 20 31 137 21 1.77 .91–3.47 .09 19 33 103 24 1.89 .92–3.86 .08

Missing 21 32 213 33 0.98 .29–3.25 .97 18 32 121 28 1.58 .33–7.61 .57

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; OST, opioid substitution therapy.

a

In model a), the “No” category includes 4 controls with missing route of heroin administration and 9 cases who did not report taking heroin (consisting of 2

cases who reported taking other illicit drugs, 6 cases who reported taking no illicit drugs, and 1 case missing this information); in model b), it includes 6 cases

who did not report taking heroin (consisting of 1 case who reported taking other illicit drugs, 4 cases who reported taking no illicit drugs, and 1 case missing this

information).

consumption were positively associated with anthrax infection. aerobic, this is perhaps less likely to be the case here. The as-

We also found that only smoking heroin was associated with sociation between anthrax and longer injecting career may

lower risk of infection. The risk factors identified in this study reflect the poorer health and therefore greater susceptibility to

are consistent with the hypotheses developed, but not formally infection of long-term drug users [9, 10]. Similarly, the associ-

confirmed, in the investigation of the anthrax outbreak [2]. ation between alcohol and anthrax may reflect higher sus-

Notably, we did not find an association between sharing in- ceptibility to infection due to alcohol’s immunosuppressive

jecting equipment and anthrax infection. This is consistent effects [11].

with other evidence, described in the outbreak report [2], With regard to route of heroin administration and risk of

which strongly points to the heroin itself as the source of in- infection, it is conceivable that the intravenous administration

fection. The latter is also supported by the observed correla- of heroin is more conducive to the germination of spores and

tion between length of injecting and infection: whereas we proliferation of vegetative organisms than smoking/inhaling

might have expected younger, less experienced drug users— heroin. However, inhalation of anthrax spores via heroin inha-

who tend to engage in riskier behavior [6]—to have a greater lation/smoking is a biologically plausible route of infection,

burden of infection, the opposite was observed. Older age/ and evidence from the outbreak case histories verified that in-

longer injecting career have previously been implicated in bac- fection did occur in noninjecting heroin users, including at

terial soft tissue infections among injectors, which may have least 1 fatal case.

been explained by the higher propensity for older individuals The finding that those who were currently receiving OST

to inject into the skin/muscle—an anaerobic environment in were more likely to have had anthrax was significant, even

which Clostridia species proliferate [7, 8]. Since B. anthracis is after adjustment for time since onset of injecting.

BRIEF REPORT • CID 2012:55 (1 September) • 709

Nevertheless, there may still be residual confounding and this criminal justice). Understanding the risk factors for anthrax

association may simply reflect the more problematic and long- infection may help to inform risk communication in future

standing drug use of the anthrax cases, since the likelihood of outbreaks of anthrax or other bacterial infections affecting

being in treatment for drug use increases with increasing drug users.

length and severity of drug use.

This study has a number of limitations. First, because the Notes

linked data was from a preexisting source (ie, it was not col-

Acknowledgments. We would like to thank Catherine Taylor from In-

lected with the specific purpose of investigating the anthrax formation Services Division of National Services Scotland for undertaking

outbreak), we were limited to examining the data that are col- the data linkage and Amanda Weir from Health Protection Scotland for

lected for drug misuse treatment. her assistance with the random selection of controls.

Financial support. This work was supported by Health Protection

Second, there was a long time delay between SDMD regis- Scotland. No direct funding was received for the study.

tration and anthrax onset for many of the cases. Thus, the be- Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

havior that was recorded during an individual’s historical All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential

Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the

attendance at a treatment facility may not be representative of content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/55/5/706/351765 by guest on 30 March 2021

his/her behavior in the period immediately preceding onset of

anthrax illness. Nevertheless, studies have demonstrated that References

drug-taking behavior can be consistent over time, particularly

1. Ramsay CN, Stirling A, Smith J, et al. An outbreak of infection with

among long-term heroin users [10], who are highly represent-

Bacillus anthracis in injecting drug users in Scotland. Euro Surveill

ed among our linked anthrax cases. 2010; 15:pii=19465.

Third, there was a large amount of missing data in the drug 2. National Anthrax Outbreak Control Team. An outbreak of anthrax

treatment records; thus, the current study was likely under- among drug users in Scotland, December 2009 to December 2010.

Available at: http://www.documents.hps.scot.nhs.uk/giz/anthrax-outbreak/

powered to detect some associations. anthrax-outbreak-report-2011-12.pdf. Accessed 28 December 2011.

Fourth, 17 anthrax cases did not link to the SDMD. Plausi- 3. Ringertz SH, Hoiby EA, Jensenius M, et al. Injectional anthrax in a

ble reasons for this could include: incomplete coverage of heroin skin-popper. Lancet 2000; 356:1574–5.

4. Information Services Division (ISD) Scotland. Drug Misuse Statistics

drug treatment services by the SDMD, that the cases had Scotland 2010. Available at: http://www.drugmisuse.isdscotland.org/

never received treatment for drug misuse, or that there were publications/10dmss/10dmss.pdf. Accessed 28 December 2011.

inaccuracies in the identifying information used for record 5. Bellis MA, Beynon C, Millar T, et al. Unexplained illness and deaths

among injecting drug users in England: a case control study using Re-

linkage. The predominance of nonlinkers from the west of

gional Drug Misuse Databases. J Epidemiol Commun H 2001;

Scotland, and Glasgow in particular (9 of the nonlinkers), 55:843–4.

likely reflects an issue with completeness of reporting of data 6. Garfein RS, Doherty MC, Monterroso ER, et al. Prevalence and inci-

dence of hepatitis C virus infection among young adult injection drug

to the SDMD in this area since mid-2009 due to the introduc-

users. J Acq Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1998; 18(suppl 1):

tion of an electronic system (Andrew Deas, Information Ser- S11–9.

vices Division, personal communication, 2012). To verify if 7. Hankins C, Palmer D, Singh R. Unintended subcutaneous and intra-

the exclusion of these cases would bias our findings, we com- muscular injection by drug users. CMAJ 2000; 163:1425–6.

8. Brett MM, Hood J, Brazier JS, Duerden BI, Hahné SJ. Soft tissue in-

pared data on injecting/smoking heroin in the week prior to fections caused by spore-forming bacteria in injecting drug users in

anthrax onset and found no statistically significant difference the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect 2005; 133:575–82.

between the linkers and nonlinkers (5% of linkers vs 0% of 9. Rosen D, Hunsaker A, Albert SM, Cornelius JR, Reynolds CF 3rd.

Characteristics and consequences of heroin use among older adults in

nonlinkers had only smoked heroin, P = .64).

the USA: a review of the literature, treatment implications, and recom-

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a method of using mendations for further research. Addict Behav 2011; 36:279–85.

routinely collected data to enable a case-control analysis where 10. Darke S, Mills KL, Ross J, Williamson A, Havard A, Teesson M. The

ageing heroin user: career length, clinical profile and outcomes across

otherwise this would not be possible, which can be used to

36 months. Drug Alcohol Rev 2009; 28:243–9.

support hypotheses and/or corroborate the findings of other 11. Szabo G. Alcohol’s contribution to compromised immunity. Alcohol

investigations (eg, epidemiological, clinical, microbiological, or Health Res World 1997; 21:30–41.

710 • CID 2012:55 (1 September) • BRIEF REPORT

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Statement of Acc Ount For Dec 2022Document3 pagesStatement of Acc Ount For Dec 2022Carl Black100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ionized Gases - Von EngelDocument169 pagesIonized Gases - Von EngelGissela MartinezNo ratings yet

- Double-Layer Bow Turban TUTORIALDocument25 pagesDouble-Layer Bow Turban TUTORIALcindmau4No ratings yet

- ECG Definition: - PurposeDocument2 pagesECG Definition: - PurposeJustine Karl Pablico100% (1)

- Performance Management and Career Planning (PPT)Document12 pagesPerformance Management and Career Planning (PPT)riya penkar100% (1)

- Proclus Commentary On The Timaeus of Plato, Book OneDocument177 pagesProclus Commentary On The Timaeus of Plato, Book OneMartin EuserNo ratings yet

- Science Olympiad 17-18 Tryout Study GuideDocument2 pagesScience Olympiad 17-18 Tryout Study Guideapi-362736764No ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Macbeth About GuiltDocument8 pagesThesis Statement For Macbeth About GuiltInstantPaperWriterCanada100% (2)

- Ebook Management and Cost Accounting 8Th Edition PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument50 pagesEbook Management and Cost Accounting 8Th Edition PDF Full Chapter PDFjohn.brown384100% (25)

- Img 20150510 0001Document2 pagesImg 20150510 0001api-284663984No ratings yet

- Code of Professional ResponsibilityDocument78 pagesCode of Professional ResponsibilityKrishna limNo ratings yet

- PHILIPPINE POPULAR CULTURE CoverageDocument17 pagesPHILIPPINE POPULAR CULTURE CoverageCasanaan Romer BryleNo ratings yet

- PAS 12 Income TaxesDocument24 pagesPAS 12 Income TaxesPatawaran, Janelle S.No ratings yet

- Std-Vii-Rise of Small Kingdoms in South India (Notes)Document5 pagesStd-Vii-Rise of Small Kingdoms in South India (Notes)niel100% (2)

- Comparative Management ModelsDocument6 pagesComparative Management Modelsmonstervarsha25% (4)

- Different Types OF: Loans and AdvancesDocument19 pagesDifferent Types OF: Loans and Advancesharesh KNo ratings yet

- Remix Artifact PlanningDocument1 pageRemix Artifact Planningapi-525109589No ratings yet

- B1 Diagnostic TestDocument3 pagesB1 Diagnostic TestDiana Patricia HURTADO OLANONo ratings yet

- Referat Bladder Trauma: Rizal TriantoDocument28 pagesReferat Bladder Trauma: Rizal TriantoTrianto RizalNo ratings yet

- Drop and Go ManifestDocument1 pageDrop and Go ManifestrosielavisNo ratings yet

- 1 SericultureDocument15 pages1 SericultureTamanna100% (1)

- Biography of IBN E SAFIDocument5 pagesBiography of IBN E SAFIToronto_ScorpionsNo ratings yet

- Honda Goldwing GL1800 Hitch Installation Guide Bushtec Motorcycle TrailersDocument13 pagesHonda Goldwing GL1800 Hitch Installation Guide Bushtec Motorcycle TrailersthegodofgodesNo ratings yet

- Wu FDocument21 pagesWu Fmary bloodNo ratings yet

- GEK1515 - L1 Introduction IVLE VersionDocument52 pagesGEK1515 - L1 Introduction IVLE VersionYan Ting ZheNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ HSG TỈNH TIẾNG ANH 11Document10 pagesĐỀ HSG TỈNH TIẾNG ANH 11trần an hạNo ratings yet

- Taylor Magazine (December 1992)Document69 pagesTaylor Magazine (December 1992)JankatDoğanNo ratings yet

- Functional Occlusion: Science-Driven ManagementDocument4 pagesFunctional Occlusion: Science-Driven Managementrunit nangaliaNo ratings yet

- The Ghost Child: A Carnage Novelette by Simeon Stoychev Smashwords EditionDocument34 pagesThe Ghost Child: A Carnage Novelette by Simeon Stoychev Smashwords EditionYojan ShresthaNo ratings yet

- MP190E34W: Technical DescriptionsDocument19 pagesMP190E34W: Technical DescriptionsBroCactusNo ratings yet