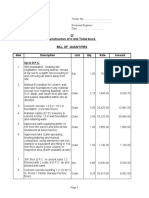

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Are Stable Coins Stable?: Usman W. Chohan, Mba, PHD

Uploaded by

Quentin VandeweyerOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Are Stable Coins Stable?: Usman W. Chohan, Mba, PHD

Uploaded by

Quentin VandeweyerCopyright:

Available Formats

Are Stable

Coins Stable?1

29th March, 2020 2

Usman W. Chohan, MBA, PhD 3

Discussion Paper Series: Notes on the 21st Century

Abstract: Stable coins attempt to resolve the problem of wide

volatility in dollar-denominated prices that characterize most

cryptoinstruments, by “pegging”their value to fixed amounts of

traditional monetary instruments. This discussion paper considers

the challenges faced by “stable coin” cryptocurrencies, at

different levels of collateralization, through comparison with

pegged currencies, which follow a similar dynamic in terms of

maintaining support for a given monetary value. Thepaper suggests

that the novelty of cryptocurrencies should not detract from

observing what are fundamental difficulties in constructing pegs

to traditional currencies.

1

This paper formed the basis of the Crypto Research Report’s first

podcast:

https://cryptoresearchnewsletter.substack.com/p/introducing-the-academic

-blockchain?fbclid=IwAR1NwuB6BoiSoi1pN1IU6pE26lvLkzESGZ-r91J_StMV7wbOUez

t9zhRZcU

2

Originally published on SSRN on January 24th, 2019

3

Critical

Blockchain Research Initiative (CBRI)

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

1

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

2

Are Stable Coins Stable?

Cryptocurrencies have generally been characterized by wide

fluctuations in their dollar-denominated prices. This volatility

has proven dissuasive to users as a unit of account and store of

value, and to a portion of traditional investors attempting to

grapple with what is already a complex domain and novel asset

class. However, anew breed of cryptocurrencies, termed “stable

coins,” have emerged in the recent past with an approach to

mitigate this volatility through a sustained peg (or in

cryptocurrency jargon, a “tether”) with traditional instruments

such as the US dollar or a basket of currencies.In addition,

tethers can be constructed against other assets such as oil and

gold; and perhaps even more interestingly, a peg between

cryptocurrencies themselves. The pegging itself can be conducted

using deliberate issuance of coin, deliberate transactions with

other assets, or through an algorithm that maintains the pegged

relationship using pre-programmed code, buying and selling as

required.

Do such concepts resolve the problem of volatility without raising

new concerns in turn? Pondering this question, the purpose of

this discussion paper is to consider the challenges faced by

“stable coin” cryptocurrencies through comparison with pegged

currencies, which follow a similar dynamic (depending on their

level of collateralization) in terms of maintaining support for a

given monetary-value peg.The paper suggests that the novelty of

cryptocurrencies should not detract from observing what are

fundamental difficulties in constructing pegs (or tethers)

totraditional currencies.In what has culminated in a substantial

public interest in cryptocurrencies and aburst of research into

the promise of blockchain technology at the global level, it is

also worth noting that these novel and alternative assets face a

series of problems that traditional asset classes too have

grappled with. Tethering (pegging) the value of stable coins, at

different levels of collateralization,is but one such example

that has borne out many a times in traditional currencies.

The most prominent names among the stable coins are

Tether,

Basis,

Digix,

and

Sagacoin

,but newer names continue to enter the space

as of this writing. Their value is generally rigidly tied to a

specific currency such as the dollar or euro, or in turn pegged

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

3

to a basket of national currencies.4 Pegging appears

prima facie

to be a useful solution to the volatility problem, which would

allow for greater adoption of cryptocurrencies across societies.

The value of stable coins is “stable” on a dollar-denominated

basis, which makes them more viable as units of account or stores

of value. This would also seem to remove some of the speculative

aspect underlying the prices of cryptoinstruments. However, a

closer inspection of the challenges to using tethered crypto

instruments leaves some of the optimism directed towards them to

dissipate, irrespective of the level of collateralization of the

coin, which can be seen conceptually by segmenting the problem

into fully collateralized, partially collateralized, and

uncollateralized cryptoinstruments.

As of this writing, the most prominent stable coin is

Tether

, which

is purportedly a fully collateralized coin, although the claim

has been disputed.First, for a fully collateralized coin, i.e.

one whose value is fully pegged to a traditional currency on a

1-to-1 basis, the coin issuer must hold reserves in excess(or at

least equal to) the value of circulating coins, which raises

expenses in terms of5 See discussion in Chohan 2018lElectronic

copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=33268233raising

capital, as well as issues with respect to their scalability.

Tether

is an example of one such cryptocurrency which claims to

have coins in reserve greater than those in circulation. However,

a lack of transparency regarding Tether’s mechanism has led this

to be disputed.7Second, for a partially collateralized coin, the

problems of bank runs emerge, as they would in pegs of

traditional currencies which are at risk.

A partial collateralization implies a fractional reserve pegging

mechanism, as is found in traditional currencies(particularly

those of emerging markets), where pegging at only a portion of

the reserve heightens the risk of coin holders selling whenever

the durability of the pegis in question. This in turn depends on

the actual reserves held by the coin issuer.Due to a lack of

transparency among coin issuers (such as Tether), there are risks

ofbank run behaviour, further combustible due to the mercurial

attitudes of a segment of investors towards cryptocurrencies. In

a crisis event, the coin issuer shall be forced to purchase its

4

Alternatively, as mentioned earlier, the pegging can be conducted against

a basket of cryptocurrencies or against other assets such as oil or

gold.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

4

issuance using its dollar reserves to prevent the coin’s price

from precipitous falls. This could be done in a manual or

algorithmic fashion. The durability of the peg, already a tough

proposition given the trust deficit faced by cryptocurrencies

issuers, is therefore a key determinant in such conditions.

Third, for uncollateralized coins, the need for transparency and

bridging the trust deficit is even greater. A coin issuer that is

uncollateralized and pegged would require not just coin issuance

but some time of additional instrument, such as a fixed income

issuance (“crypto-bonds,” so to speak5), with the interest repaid

in coins. At falling price levels for the coin, the issuer would

be forced to buy the coins through the emission of additional

crypto-bonds,and these bonds would need to be emitted at below

par value (at a discount), so as to attract fixed-income

investors with the potential of a price rise, in addition to the

coin-bearing interest. Coin-bearing interest would be premised on

future earned income through issuances. For this to occur, the

issuer would require ever larger fixed-income emissions (a high

growth trajectory), which in turn would depend on investor

interest in such an asset.

Without future issuances, current interest liabilities will not be

met, and so greater discounts or higher coin interest rates would

need to be applied, exacerbating the problem over time. This

would destroy the issuer’s ability to maintain the peg. In sum,

irrespective of the level of collateralization, stable coin

issuers will face substantial challenges, relating to credibility

of their pegs and resources to assure the viability of the peg,

that are often present in currencies (particularly in emerging

markets) where pegs have at times not been sustainable. At full

collateralization,substantial reserves will need to be held,

which would also need the assurance of transparency, which in

current cases has been left wanting. At partial

collateralization, the tether (peg) will be susceptible to

traditional bank-run behaviour. At no collateralization, coin

5

The term crypto-bonds is used distinctively from the recent trend of

mainstream institutions to issue bond that are denoted on a blockchain.

One example of this is the Chinese issuance of “cryptobonds,” and

another is the World Bank commissioning the Commonwealth Bank of

Australia to build a bond that is underwritten with some blockchain

element. These are not examples of the sense in which a crypto-bond is

used here, as a fixed income instrument that provides an additional

justification for investors in uncollateralized stablecoins.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

5

issuers would need to emit fixed-income instruments which would

be even more susceptible to bank-run behaviour.

As of this writing, the precipitous decline in cryptocurrencies, and

the marked volatility of the larger (and unpegged)

cryptocurrencies would suggest that investor appetite for such

risk is far lower than in the period 2015-2017. While volatility

is an issue that is

prima facie

dealt with through tethers, the

viability of such a tether - or to put it another way: the

stability of the stable coin - remains an open question,

irrespective of the level of collateralization, and particularly

more so for lower levels of collateralized cryptocurrencies.

For this reason, the most common usage of stablecoins is as

intermediate instruments that help investors to hedge bets and

smoothen their transactions on crypto-exchanges. This is a

utility function that is quite limited to the specific

exchange-oriented investor that facilitates their transaction

requirements in the absence of larger capital markets and deeper

pools of capital on the exchanges.

In the long-run, stablecoins may become a redundant technology

because of the intermediary function they serve. Stablecoins are

in fact a “translation device” between traditional finance and

cryptocurrencies. However, if and when cryptocurrencies receive

widespread adoption, they will form a natural comparative

relationship with traditional asset classes. In that case, having

stablecoins to peg cryptoinstruments will be an unnecessary

feature. This is ultimately the goal that cryptoanarchists and

casual investors alike would yearn for: wider and deeper capital

markets for cryptocurrencies where devices of pegging and

comparison no longer pose a need.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

6

References

1. Abdullah, S., Rothenberg, S., Siegel, E., & Kim, W. (2020).

School of Block–Review of Blockchain for the Radiologists.

Academic Radiology, 2

7

(1), 47-57.

2. Abramowicz, M. (2016). Cryptocurrency-based law. Ariz. L. Rev.

,

58

, 359.

3. Adhami, S., & Giudici, G. (2019). Initial Coin Offerings: Tokens

as Innovative Financial Assets. In Blockchain Economics and

Financial Market Innovation(pp. 61-81). Springer, Cham.

4. Ahvenainen, T. (2018). Kryptovaluutat piensijoittajan

näkökulmasta.

5. Albrecht, S., Lutz, B., & Neumann, D. (2019). How Sentiment

Impacts the Success of Blockchain Startups-An Analysis of Social

Media Data and Initial Coin Offerings. In H ICSS(pp. 1-10).

6. Albrecht, S., Lutz, B., & Neumann, D. (2019). The behavior of

blockchain ventures on Twitter as a determinant for funding

success. Electronic Markets, 1-17.

7. Antonopoulos, A. M. (2014). Mastering Bitcoin: unlocking digital

cryptocurrencies. " O'Reilly Media, Inc.".

8. Aивлиева, А. А. (2018). ПРОГНОЗИРОВАНИЕ УСПЕШНОСТИ ПРОЕКТОВ НА

ICO.

9. Бабінська, О. В. (2017). Криптовалюта: правовий аспект. Вісник

Чернівецького торговельно-економічного інституту. Економічні

науки

, (4), 183-188.

10. Baele, L., & Dodebier, D. (2017). Could cryptocurrencies

contribute to a well-diversified portfolio for European

investors?.

11. Bahrawy, A., Alessandretti, L., Kandler, A., Pastor-Satorras,

R., & Baronchelli, A. (2017). Evolutionary dynamics of the

cryptocurrency market. R oyal Society open science,

4

(11), 170623.

12. Barbosa, A. C., Oliveira, T. A., & Coelho, V. N. (2018, July).

Cryptocurrencies for smart territories: an exploratory study. In

2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN)

(pp. 1-8). IEEE.

13. Bech, M. L., & Garratt, R. (2017). Central bank

cryptocurrencies. BIS Quarterly Review September .

14. Bellini, E., Iraqi, Y., & Damiani, E. (2020). Blockchain-based

Distributed Trust and Reputation Management Systems: A Survey.

IEEE Access.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

7

15. Belotti, M., Božić, N., Pujolle, G., & Secci, S. (2019). A

Vademecum on Blockchain Technologies: When, Which, and How. IEEE

Communications Surveys & Tutorials ,

21

(4), 3796-3838.

16. Bian, S., Deng, Z., Li, F., Monroe, W., Shi, P., Sun, Z., ...

& Zhang, T. (2018). Icorating: A deep-learning system for scam

ICO identification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.03670 .

17. Bianchetti, M., Ricci, C., & Scaringi, M. (2018). Are

cryptocurrencies real financial bubbles? Evidence from

quantitative analyses. E vidence from Quantitative Analyses

(February 24, 2018). A version of this paper was published in

Risk

, 2

6

.

18. Camilla, N. (2019). Decentralised Monetary Systems. A vailable

at SSRN 3498841

.

19. Caporale, G. M., Gil-Alana, L., & Plastun, A. (2018).

Persistence in the cryptocurrency market. R esearch in

International Business and Finance ,

46

, 141-148.

20. Chan, S., Chu, J., Nadarajah, S., & Osterrieder, J. (2017). A

statistical analysis of cryptocurrencies. J ournal of Risk and

Financial Management,

10(2), 12.

21. Chatterjee, A., Pitroda, Y., & Parmar, M. (2020). Dynamic

Role-Based Access Control for Decentralized Applications. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2002.05547 .

22. Chatterjee, K., Goharshady, A. K., & Pourdamghani, A. (2019,

May). Probabilistic smart contracts: Secure randomness on the

blockchain. In 2

019 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain

and Cryptocurrency (ICBC)(pp. 403-412). IEEE.

23. Chatterjee, K., Goharshady, A. K., & Goharshady, E. K. (2019,

April). The treewidth of smart contracts. In Proceedings of the

34th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing(pp. 400-408).

24. Chodhury, N. (2019). I nside Blockchain, Bitcoin, and

Cryptocurrencies

. CRC Press.

25. Chod, J., & Lyandres, E. (2018). A theory of icos:

Diversification, agency, and information asymmetry. A gency, and

Information Asymmetry (July 18, 2018) .

26. Chuen, D. L. K., Guo, L., & Wang, Y. (2017). Cryptocurrency: A

new investment opportunity?. The Journal of Alternative

Investments

, 2

0

(3), 16-40.

27. Ciatto, G., Calegari, R., Mariani, S., Denti, E., & Omicini,

A. (2018, June). From the Blockchain to Logic Programming and

Back: Research Perspectives. In W OA(pp. 69-74).

28. Chohan, U.W. (2016) The Panama Papers and Tax Morality.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2759418

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

8

29. Chohan, U.W. (2017a). Cryptocurrencies: A Brief Thematic

Review.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3024330

30. Chohan, U.W. (2017b).Assessing the Differences in Bitcoin &

Other Cryptocurrency Legality Across National Jurisdictions.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3042248

31. Chohan, U.W. (2017c). A History of Bitcoin.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3047875

32. Chohan, U.W. (2017d). Cryptoanarchism and Cryptocurrencies.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3079241

33. Chohan, U.W. (2017e). Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs): Risks,

Regulation, and Accountability.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3080098

34. Chohan, U.W. (2017f). The Decentralized Autonomous

Organization and Governance Issues.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3082055

35. 郭笑春, & 胡毅. (2020). 数字货币时代的商业模式讨论——基于双案例的比较研

究. 管 理评论 ,

32

(1), 324-336.

36. Chohan, U.W. (2017g). The Double Spending Problem and

Cryptocurrencies.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3090174

37. Chohan, U.W. (2017l). Independent Budget Offices and the

Politics–Administration Dichotomy. International Journal of Public

Administration. 41 (12), 1009-1017

38. Chohan, U.W. (2017m). What is a Charter of Budget Honesty? The

Case of Australia. Canadian Parliamentary Review. 40(1), 11-15.

39. Chohan, U.W. (2017n). Qu’est-ce qu’une charte d'honnêteté

budgetaire? Le cas d’Australie. R evue Parlementaire Canadienne.

40(1), 11-15.

40. Chohan, U.W. (2017p). “Public Value as Rhetoric: A Budgeting

Approach.” International Journal of Public Administration. 41

(15), 1217-1227.

41. Chohan, U.W. (2018c). The Roles of Independent Legislative

Fiscal Institutions: A Multidisciplinary Analysis. UNSW,

Canberra, Australia.

42. Чахова, Д. А., & Кошелева, А. И. (2018). Проблемы и

перспективы развития блокчейн-туризма в регионах РФ (на примере

Калужской области). Региональная экономика и управление:

электронный научный журнал, (2018-53).

43. Chohan, U.W. (2018g). Proof-of-Stake Algorithmic Methods: A

Comparative Summary

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3131897

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

9

44. Chohan, U.W. (2018h). Oversight and Regulation of

Cryptocurrencies: BitLicense.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3133342

45. Chohan, U.W. (2018i). Blockchain and the Extractive

Industries: Cobalt Case Study.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3138271

46. Chohan, U.W. (2018k). The Concept and Criticisms of Steemit.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3129410

47. Chohan, U.W. (2019a). Public Value and Budgeting:

International Perspectives: Routledge.

48. Chohan, U.W. (2019g). Are Cryptocurrencies Truly Trustless?

Cryptocurrencies and Mechanisms of Exchange.

Springer.

49. Chohan, U.W. (2019h). Are Stable Coins Stable?

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3326823

50. Chohan, U.W. (2019i). The Limits to Blockchain? Scaling vs.

Decentralization.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3338560

51. Chohan, U.W. (2019j). Cryptocurrencies and Hyperinflation.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3322329

52. Chohan, U.W. (2019k). Cryptocurrencies and Inequality.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3322329

53. Chohan, U.W. (2020a). Some Precepts of the Digital Economy.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3512353

54. Chohan, U.W. (2020b). Reimagining the Public Manager:

Delivering Public Value. Routledge, UK.

55. Chohan, U.W. (2020c). A Post-Coronavirus World: 7 Points of

Discussion for a New Political Economy. CASS Working Papers on

Economics & National Affairs No. EC015UC

56. Chohan, U.W. (2020d). Tax Evasion & Whistleblowers: Curious

Policy or Durable Strategy?. CASS Working Papers on Economics &

National Affairs.

57. Chohan,U.W. and D'Souza, A.P. (2020). The Joys & Ills of

Social Media: A Review.

58. Danila, Ş. C., & Robu, I. B. (2019). The Influence of

Cryptocurrency Bitcoin over the Romanian Capital Market. A udit

Financiar

,

57

(155).

59. Decourt, R.F.; Chohan, U.W.; Perugini, M.L. (2017). “Bitcoin

returns and the Monday Effect.” Conference Proceedings of the 14th

Convibra: Administração (Brazil).November.

http://www.convibra.com.br/upload/paper/2017/33/2017_33_14675.pdf

60. Gesso, C.(2020). Eco-Sustainable Metropolises: An Analysis of

Budgetary Strategy in Italy‟s Largest Municipalities.

International Journal of Business Administration.11(2).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

10

61. Huang, W., Meoli, M., & Vismara, S. (2019). The geography of

initial coin offerings. S mall Business Economics , 1-26.

62. Hrga, A., Benčić, F. M., & Žarko, I. P. (2019, July).

Technical Analysis of an Initial Coin Offering. In 2019 15th

International Conference on Telecommunications (ConTEL)(pp. 1-8).

IEEE.

63. Jiang, H., Liu, D., Ren, Z., & Zhang, T. (2018). Blockchain in

the eyes of developers. a rXiv preprint arXiv:1806.07080 .

64. Joo, M. H., Nishikawa, Y., & Dandapani, K. (2019). ICOs, the

next generation of IPOs. Managerial Finance

.

65. Kabir, S. M. H., Chowdhury, M. A. M., Aktaruzzaman, M., &

Rahman, M. M. The Role of Islamic Crypto Currency in Supporting

Economic Growth of Malaysia.

66. Kadam, S. (2018, March). Review of Distributed Ledgers: The

technological Advances behind cryptocurrency. In I nternational

Conference Advances in Computer Technology and Management

(ICACTM)

.

67. Kozubík197, A. (2018). On the Risk Factors of the Yield in the

Cryptocurrencies Market. Recent Advances in Information

Technology, Tourism, Economics, Management and Agriculture , 507.

68. Malinova, K., & Park, A. (2018). Tokenomics: when tokens beat

equity. Available at SSRN 3286825.

69. Mann, T. J. (2019). Blockchain Technology-China's Bid to High

Long-Run Growth. Gettysburg Economic Review

, 11

(1), 5.

70. Othman, A. H. A., Alhabshi, S. M., & Haron, R. (2019). The

effect of symmetric and asymmetric information on volatility

structure of crypto-currency markets. Journal of Financial

Economic Policy.

71. Pant, D. R., Neupane, P., Poudel, A., Pokhrel, A. K., & Lama,

B. K. (2018, October). Recurrent neural network based bitcoin

price prediction by twitter sentiment analysis. In 2018 IEEE 3rd

International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security

(ICCCS)(pp. 128-132). IEEE.

72. Shahnaz, A., Qamar, U., & Khalid, A. (2019). Using Blockchain

for Electronic Health Records. IEEE Access

, 7

, 147782-147795.

73. Stübinger, J. (2019). Statistical arbitrage with optimal

causal paths on high-frequency data of the S&P 500. Quantitative

Finance

, 19

(6), 921-935.

74. Vlcek, F. Virtual Currencies: A New Challenge for Tax Law and

Monetary Law.

75. Vyhovska, N., Polchanov, A., Frolov, S., & Kozmenko, Y.

(2018). The Effect of IT-Transformation of the Country’s

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

11

Financial Potential during the Post-Conflict Reconstruction/

Public and Municipal Finance

, 7

(3), 15-25.

76. van Rijmenam, M., Schweitzer, J., & Williams, M. A. A

Distributed Future: Where Blockchain Technology Meets

Organisational Design and Decision-Making.

77. Willrich, S., Melcher, F., Straub, T., & Weinhardt, C. (2019).

Towards More Sustainability: A Literature Review Where Bioeconomy

Meets Blockchain.

78. Yilmaz, K. N., & Hazar, B. H. (2018). Pre dicting future

cryptocurrency investment trends by conjoint analysis. Journal of

Economics, Finance and Accounting (JEFA)

, 5

(4).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326823

You might also like

- Bondar - Stablecoins From Electronic Money On Blockchain To A Cryptocurrency Basket PDFDocument97 pagesBondar - Stablecoins From Electronic Money On Blockchain To A Cryptocurrency Basket PDFДмитрий БондарьNo ratings yet

- Maxwell Murialdo - Can A Stablecoin Be Collateralized by A Fully Decentralized, Physical AssetDocument42 pagesMaxwell Murialdo - Can A Stablecoin Be Collateralized by A Fully Decentralized, Physical AssetJose Gonzalez AntomilNo ratings yet

- Types of Stablecoins: Bitcoin EtherDocument3 pagesTypes of Stablecoins: Bitcoin Etherneyer vpNo ratings yet

- The Crypto Revolution: A Guide to Building Wealth with CryptocurrenciesFrom EverandThe Crypto Revolution: A Guide to Building Wealth with CryptocurrenciesNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Guide To Stable CoinsDocument25 pagesThe Ultimate Guide To Stable CoinsJoe DagherNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1062940822001735 MainDocument26 pages1 s2.0 S1062940822001735 MainMay SamyNo ratings yet

- Celo: A Stablecoin Ecosystem For The Real-World Defi: ResearchDocument12 pagesCelo: A Stablecoin Ecosystem For The Real-World Defi: ResearchNguyen PhuocNo ratings yet

- Hayek Money by AmetranoDocument51 pagesHayek Money by AmetranoYousef abachirNo ratings yet

- Terra White PaperDocument16 pagesTerra White Paperkr2983No ratings yet

- Stablecoins - Coinbase White PaperDocument39 pagesStablecoins - Coinbase White PaperNalanda Public School Kinder Garten. OngoleNo ratings yet

- 3 Opening - Discussion - On - BankingDocument35 pages3 Opening - Discussion - On - BankinggemaclawNo ratings yet

- Cryptoliquidity: The Blockchain and Monetary StabilityDocument42 pagesCryptoliquidity: The Blockchain and Monetary StabilityIguaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0275531919311146 MainDocument18 pages1 s2.0 S0275531919311146 MainМария МихалеваNo ratings yet

- Blockchain Structure and Cryptocurrency PricesDocument71 pagesBlockchain Structure and Cryptocurrency PricesMarcos del RíoNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Finance - 2023 - Alexander - Crypto Quanto and Inverse OptionsDocument39 pagesMathematical Finance - 2023 - Alexander - Crypto Quanto and Inverse OptionsAny “AnyMu” MuanalifahNo ratings yet

- What Are Stablecoins?: Nearly Every IndustryDocument11 pagesWhat Are Stablecoins?: Nearly Every IndustryJonas BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Should We Fear Stablecoins by Lawrence H. WhiteDocument6 pagesShould We Fear Stablecoins by Lawrence H. WhiteLegal KidNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Approaches To Regulating Decentralized FinanceDocument5 pagesChallenges and Approaches To Regulating Decentralized FinanceAakankshaNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrencies and Digital Assets - Market Structure, Risks, and OpportunitiesDocument4 pagesCryptocurrencies and Digital Assets - Market Structure, Risks, and Opportunitiessiquanmo123No ratings yet

- SSRN Id3211745Document42 pagesSSRN Id3211745Cypag Asistente Rev fiscalNo ratings yet

- Last PartDocument3 pagesLast PartJuniorsNo ratings yet

- Stablecoins: Growth Potential and Impact On BankingDocument26 pagesStablecoins: Growth Potential and Impact On BankingNicolas CassanelloNo ratings yet

- Crypto CurrenciesDocument10 pagesCrypto CurrenciesVinay KumarNo ratings yet

- العملات الافتراضية - تقارير بنك التوسيات الدولى BISDocument6 pagesالعملات الافتراضية - تقارير بنك التوسيات الدولى BISWael HassanNo ratings yet

- MONETARY POLICY - in The Digital AgeDocument4 pagesMONETARY POLICY - in The Digital AgeEbNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0377221722005975 MainDocument16 pages1 s2.0 S0377221722005975 Mainsonia969696No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1057521918304095 MainDocument17 pages1 s2.0 S1057521918304095 MainSinggih HadiNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Maker Protocol: October 29, 2022Document15 pagesUnderstanding The Maker Protocol: October 29, 2022Athanasios TsagkadourasNo ratings yet

- Brainard 20220708 ADocument12 pagesBrainard 20220708 AJoey MartinNo ratings yet

- 09 StablecoinsDocument56 pages09 Stablecoinsayush agarwalNo ratings yet

- Criptocurrencies and Monetary PolicyDocument13 pagesCriptocurrencies and Monetary PolicyFelipe Kiritschenko Oliveira Bastos SilvaNo ratings yet

- BIS Working Papers: The Digitalization of MoneyDocument35 pagesBIS Working Papers: The Digitalization of Money5ty5No ratings yet

- Rbi Dy Gov Crypto 20220214Document12 pagesRbi Dy Gov Crypto 20220214bruhuhuNo ratings yet

- TheDeFinvestor STABLECOINSDocument7 pagesTheDeFinvestor STABLECOINSlishengminNo ratings yet

- Crypto 1Document4 pagesCrypto 1khan.sarim1971No ratings yet

- How To Value Payment Tokens 0.5. v2Document14 pagesHow To Value Payment Tokens 0.5. v2Distro MusicNo ratings yet

- Is Bitcoin Really UntetheredDocument52 pagesIs Bitcoin Really UntetheredFinance Master rechercheNo ratings yet

- English Vietnamese What Is Cryptocurrency?Document8 pagesEnglish Vietnamese What Is Cryptocurrency?SunnyNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrencies and The Future of Money: Mcmaster University, Hamilton, Canada Mit, Cambridge, UsaDocument22 pagesCryptocurrencies and The Future of Money: Mcmaster University, Hamilton, Canada Mit, Cambridge, UsaAtul MhatreNo ratings yet

- 5 Social EngineeringDocument5 pages5 Social EngineeringmittleNo ratings yet

- Taming Wildcat StablecoinsDocument49 pagesTaming Wildcat StablecoinsForkLogNo ratings yet

- An Overview of StablecoinDocument26 pagesAn Overview of StablecoinBankole AyoadeNo ratings yet

- Crypto CurrenciesDocument18 pagesCrypto Currenciesศรุต พึ่งพระNo ratings yet

- Tether BTC Scam SSRN Id3195066 PDFDocument119 pagesTether BTC Scam SSRN Id3195066 PDFJohn NovakNo ratings yet

- Inverse and Quanto Inverse Options in A Black-Scholes WorldDocument36 pagesInverse and Quanto Inverse Options in A Black-Scholes WorldJulien KuntzNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0165188921000907 MainDocument26 pages1 s2.0 S0165188921000907 MainAndini valentinaNo ratings yet

- Occasional Paper Series: in Search For Stability in Crypto-Assets: Are Stablecoins The Solution?Document55 pagesOccasional Paper Series: in Search For Stability in Crypto-Assets: Are Stablecoins The Solution?Quentin VandeweyerNo ratings yet

- 1.introduction To Cryptocurrencies Cryptocurrency Design and Economics 1Document4 pages1.introduction To Cryptocurrencies Cryptocurrency Design and Economics 1professor9980No ratings yet

- Discuss The Role of Asset Pricing in Finance and Investing .Discuss The Market Model and What Beta IsDocument7 pagesDiscuss The Role of Asset Pricing in Finance and Investing .Discuss The Market Model and What Beta IsMuhammad UsmanNo ratings yet

- This Document Is Being Provided For The Exclusive Use of TATEO JAGERDocument5 pagesThis Document Is Being Provided For The Exclusive Use of TATEO JAGERmittleNo ratings yet

- The Reasons Behind The Crashing Crypto MarketDocument5 pagesThe Reasons Behind The Crashing Crypto MarketmanishaNo ratings yet

- Internet Wildcat Banking or Always-On Dollars?: 10 Stablecoin MythsDocument20 pagesInternet Wildcat Banking or Always-On Dollars?: 10 Stablecoin MythsTrina KundiNo ratings yet

- IG Bloomberg CryptoebookDocument12 pagesIG Bloomberg CryptoebookTHAN HAN100% (1)

- Investment ProposalDocument4 pagesInvestment ProposalRohit MethilNo ratings yet

- Crypto-Assets - The Global Regulatory PerspectiveDocument20 pagesCrypto-Assets - The Global Regulatory PerspectiveJeremy CorrenNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrency Development and Digital Mining ProcessDocument11 pagesCryptocurrency Development and Digital Mining ProcessnhoporegNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of High APY Decentralized Autonomous Organizations in The Blockchain EcosystemDocument8 pagesThe Rise and Fall of High APY Decentralized Autonomous Organizations in The Blockchain EcosystemIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Occasional Paper Series: in Search For Stability in Crypto-Assets: Are Stablecoins The Solution?Document55 pagesOccasional Paper Series: in Search For Stability in Crypto-Assets: Are Stablecoins The Solution?Quentin VandeweyerNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3722314Document195 pagesSSRN Id3722314Quentin Vandeweyer100% (1)

- Money Stuff Maybe SPACs Are Really IPOsDocument15 pagesMoney Stuff Maybe SPACs Are Really IPOsQuentin VandeweyerNo ratings yet

- Its Time For A Venial Value Timing SinDocument16 pagesIts Time For A Venial Value Timing SinQuentin VandeweyerNo ratings yet

- Uncolat BsDocument1 pageUncolat BsQuentin VandeweyerNo ratings yet

- Buffett's Alpha: Andrea Frazzini, David Kabiller, and Lasse Heje PedersenDocument34 pagesBuffett's Alpha: Andrea Frazzini, David Kabiller, and Lasse Heje PedersenRafaelNo ratings yet

- Reserve Fund BsDocument1 pageReserve Fund BsQuentin VandeweyerNo ratings yet

- CE5215-Theory and Applications of Cement CompositesDocument10 pagesCE5215-Theory and Applications of Cement CompositesSivaramakrishnaNalluriNo ratings yet

- Business Occupancy ChecklistDocument5 pagesBusiness Occupancy ChecklistRozel Laigo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Land Use Paln in La Trinidad BenguetDocument19 pagesLand Use Paln in La Trinidad BenguetErin FontanillaNo ratings yet

- 1.6 Program AdministrationDocument56 pages1.6 Program Administration'JeoffreyLaycoNo ratings yet

- Karmex 80df Diuron MsdsDocument9 pagesKarmex 80df Diuron MsdsSouth Santee Aquaculture100% (1)

- Tech Mahindra Sample Verbal Ability Placement Paper Level1Document11 pagesTech Mahindra Sample Verbal Ability Placement Paper Level1Madhav MaddyNo ratings yet

- Optimization of Crude Oil DistillationDocument8 pagesOptimization of Crude Oil DistillationJar RSNo ratings yet

- Electric Arc Furnace STEEL MAKINGDocument28 pagesElectric Arc Furnace STEEL MAKINGAMMASI A SHARAN100% (3)

- Central Banking and Monetary PolicyDocument13 pagesCentral Banking and Monetary PolicyLuisaNo ratings yet

- WhatsNew 2019 enDocument48 pagesWhatsNew 2019 enAdrian Martin BarrionuevoNo ratings yet

- Industrial Management: Teaching Scheme: Examination SchemeDocument2 pagesIndustrial Management: Teaching Scheme: Examination SchemeJeet AmarsedaNo ratings yet

- Ap06 - Ev04 Taller en Idioma Inglés Sobre Sistema de DistribuciónDocument9 pagesAp06 - Ev04 Taller en Idioma Inglés Sobre Sistema de DistribuciónJenny Lozano Charry50% (2)

- SPIE Oil & Gas Services: Pressure VesselsDocument56 pagesSPIE Oil & Gas Services: Pressure VesselsSadashiw PatilNo ratings yet

- Computer Vision and Action Recognition A Guide For Image Processing and Computer Vision Community For Action UnderstandingDocument228 pagesComputer Vision and Action Recognition A Guide For Image Processing and Computer Vision Community For Action UnderstandingWilfredo MolinaNo ratings yet

- Spine Beam - SCHEME 4Document28 pagesSpine Beam - SCHEME 4Edi ObrayanNo ratings yet

- Certification DSWD Educational AssistanceDocument3 pagesCertification DSWD Educational AssistancePatoc Stand Alone Senior High School (Region VIII - Leyte)No ratings yet

- Pet Care in VietnamFull Market ReportDocument51 pagesPet Care in VietnamFull Market ReportTrâm Bảo100% (1)

- Massive X-16x9 Version 5.0 - 5.3 (Latest New Updates in Here!!!)Document158 pagesMassive X-16x9 Version 5.0 - 5.3 (Latest New Updates in Here!!!)JF DVNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam StatconDocument4 pagesMidterm Exam Statconlhemnaval100% (4)

- Cencon Atm Security Lock Installation InstructionsDocument24 pagesCencon Atm Security Lock Installation InstructionsbiggusxNo ratings yet

- ARISE 2023: Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Engineering, Navi MumbaiDocument5 pagesARISE 2023: Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Engineering, Navi MumbaiGAURAV DANGARNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law I Green Notes PDFDocument105 pagesCriminal Law I Green Notes PDFNewCovenantChurchNo ratings yet

- Computer System Sevicing NC Ii: SectorDocument44 pagesComputer System Sevicing NC Ii: SectorJess QuizzaganNo ratings yet

- Pharaoh TextDocument143 pagesPharaoh Textanon_31362848No ratings yet

- Ril Competitive AdvantageDocument7 pagesRil Competitive AdvantageMohitNo ratings yet

- E OfficeDocument3 pagesE Officeஊக்கமது கைவிடேல்No ratings yet

- 0901b8038042b661 PDFDocument8 pages0901b8038042b661 PDFWaqasAhmedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Walter Nicholson Microcenomic TheoryDocument15 pagesChapter 11 Walter Nicholson Microcenomic TheoryUmair QaziNo ratings yet

- Type BOQ For Construction of 4 Units Toilet Drawing No.04Document6 pagesType BOQ For Construction of 4 Units Toilet Drawing No.04Yashika Bhathiya JayasingheNo ratings yet

- Safety Inspection Checklist Project: Location: Inspector: DateDocument2 pagesSafety Inspection Checklist Project: Location: Inspector: Dateyono DaryonoNo ratings yet

- The Dark Net: Inside the Digital UnderworldFrom EverandThe Dark Net: Inside the Digital UnderworldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (104)

- Defensive Cyber Mastery: Expert Strategies for Unbeatable Personal and Business SecurityFrom EverandDefensive Cyber Mastery: Expert Strategies for Unbeatable Personal and Business SecurityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Digital Marketing Handbook: A Step-By-Step Guide to Creating Websites That SellFrom EverandThe Digital Marketing Handbook: A Step-By-Step Guide to Creating Websites That SellRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention EconomyFrom EverandHow to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention EconomyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (421)

- More Porn - Faster!: 50 Tips & Tools for Faster and More Efficient Porn BrowsingFrom EverandMore Porn - Faster!: 50 Tips & Tools for Faster and More Efficient Porn BrowsingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (23)

- The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for PowerFrom EverandThe Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- The Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of ComputationFrom EverandThe Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of ComputationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- Branding: What You Need to Know About Building a Personal Brand and Growing Your Small Business Using Social Media Marketing and Offline Guerrilla TacticsFrom EverandBranding: What You Need to Know About Building a Personal Brand and Growing Your Small Business Using Social Media Marketing and Offline Guerrilla TacticsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (32)

- React.js Design Patterns: Learn how to build scalable React apps with ease (English Edition)From EverandReact.js Design Patterns: Learn how to build scalable React apps with ease (English Edition)No ratings yet

- So You Want to Start a Podcast: Finding Your Voice, Telling Your Story, and Building a Community That Will ListenFrom EverandSo You Want to Start a Podcast: Finding Your Voice, Telling Your Story, and Building a Community That Will ListenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (24)

- Grokking Algorithms: An illustrated guide for programmers and other curious peopleFrom EverandGrokking Algorithms: An illustrated guide for programmers and other curious peopleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- Practical Industrial Cybersecurity: ICS, Industry 4.0, and IIoTFrom EverandPractical Industrial Cybersecurity: ICS, Industry 4.0, and IIoTNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Some Websites that Offer Virtual Phone Numbers for SMS Reception and Websites to Obtain Virtual Debit/Credit Cards for Online Accounts VerificationsFrom EverandEvaluation of Some Websites that Offer Virtual Phone Numbers for SMS Reception and Websites to Obtain Virtual Debit/Credit Cards for Online Accounts VerificationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- An Internet in Your Head: A New Paradigm for How the Brain WorksFrom EverandAn Internet in Your Head: A New Paradigm for How the Brain WorksNo ratings yet

- Python for Beginners: The 1 Day Crash Course For Python Programming In The Real WorldFrom EverandPython for Beginners: The 1 Day Crash Course For Python Programming In The Real WorldNo ratings yet

- How to Start a Blog with WordPress: Beginner's Guide to Make Money by Writing OnlineFrom EverandHow to Start a Blog with WordPress: Beginner's Guide to Make Money by Writing OnlineRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Web Copy That Sells: The Revolutionary Formula for Creating Killer Copy That Grabs Their Attention and Compels Them to BuyFrom EverandWeb Copy That Sells: The Revolutionary Formula for Creating Killer Copy That Grabs Their Attention and Compels Them to BuyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Articulating Design Decisions: Communicate with Stakeholders, Keep Your Sanity, and Deliver the Best User ExperienceFrom EverandArticulating Design Decisions: Communicate with Stakeholders, Keep Your Sanity, and Deliver the Best User ExperienceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- HTML5 and CSS3 Masterclass: In-depth Web Design Training with Geolocation, the HTML5 Canvas, 2D and 3D CSS Transformations, Flexbox, CSS Grid, and More (English Edition)From EverandHTML5 and CSS3 Masterclass: In-depth Web Design Training with Geolocation, the HTML5 Canvas, 2D and 3D CSS Transformations, Flexbox, CSS Grid, and More (English Edition)No ratings yet

- Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4Chan And Tumblr To Trump And The Alt-RightFrom EverandKill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4Chan And Tumblr To Trump And The Alt-RightRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (240)