Professional Documents

Culture Documents

wei10662 fmдллллллждблжд

wei10662 fmдллллллждблжд

Uploaded by

vikaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

wei10662 fmдллллллждблжд

wei10662 fmдллллллждблжд

Uploaded by

vikaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/51881900

Original sound compositions reduce anxiety in emergency department

patients: A randomised controlled trial

Article in The Medical journal of Australia · December 2011

DOI: 10.5694/mja10.10662 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

27 283

7 authors, including:

Tracey J Weiland George Jelinek

University of Melbourne University of Melbourne

180 PUBLICATIONS 2,373 CITATIONS 264 PUBLICATIONS 5,621 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Keely Macarow Philip Samartzis

RMIT University RMIT University

7 PUBLICATIONS 32 CITATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS 31 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Raising Alterity: Working towards a just city View project

Smart Heart View project

All content following this page was uploaded by George Jelinek on 14 November 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Research

Original sound compositions reduce

anxiety in emergency department patients:

a randomised controlled trial

E

Tracey J Weiland mergency departments (EDs)

BBSc(Hons), PhD/MPsych, Abstract

Senior Research Fellow1 can provoke anxiety among

Objective: To determine whether emergency department (ED) patients’

George A Jelinek patients.1 There have been few self-rated levels of anxiety are affected by exposure to purpose-designed music

MB BS, MD, FACEM,

Academic Director 1

trials of interventions that might or sound compositions with and without the audio frequencies of embedded

reduce this anxiety. Although live per- binaural beat.

Keely E Macarow

BA, MA, PhD, formance has positive effects on Design, setting and participants: Randomised controlled trial in an ED between

Coordinator of

Postgraduate Research 2 patients and staff,2 incorporating live 1 February 2010 and 14 April 2010 among a convenience sample of adult

music in busy EDs is unrealistic. patients who were rated as category 3 on the Australasian Triage Scale.

Philip Samartzis

GradDipArt&Design, Several auditory interventions can Interventions: All interventions involved listening to soundtracks of 20 minutes’

MA, PhD, duration that were purpose-designed by composers and sound-recording

Senior Lecturer 2 modify patients’ anxiety in hospital.

artists. Participants were allocated at random to one of five groups: headphones

David M Brown The positive effect of music on anxi- and iPod only, no soundtrack (control group); reconstructed ambient noise

DipArt, MA, ety has been well demonstrated. A

PhD Candidate 2

simulating an ED but free of clear verbalisations; electroacoustic musical

review of 42 randomised contriolled composition; composed non-musical soundtracks derived from audio field

Elizabeth M Grierson

LicDip, MA, PhD, trials found that about half of them recordings obtained from natural and constructed settings; sound composition

Head of School 2 of audio field recordings with embedded binaural beat. All soundtracks were

showed that music was effective in

Craig Winter presented on an iPod through headphones. Patients and researchers were

MB BS, MBA, FACEM,

reducing perioperative pain and blinded to allocation until interventions were administered. State–trait anxiety

Director 1 anxiety.3 Reduced preoperative anxi- was self-assessed before the intervention and state anxiety was self-assessed

ety has also been associated with again 20 minutes after the provision of the soundtrack.

1 Emergency Medicine, audio featuring binaural beats, 4 Main outcome measure: Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory.

St Vincent's Hospital and

University of Melbourne,

which are apparent sounds per- Results: Of 291 patients assessed for eligibility, 170 patients completed the

Melbourne, VIC. ceived independent of physical stim- pre-intervention anxiety self-assessment and 169 completed the post-

2 School of Art, uli.5 Binaural beats are perceived intervention assessment. Significant decreases (all P < 0.001) in anxiety level

RMIT University, were observed among patients exposed to the electroacoustic musical

Melbourne, VIC. when two sounds of similar but

composition (pre-intervention mean, 39; post-intervention mean, 34), audio

Tracey.Weiland@ slightly different frequency are pre- field recordings (42; 35) or audio field recordings with embedded bianaural

svhm.org.au sented separately to each ear and beats (43; 37) when compared with those allocated to receive simulated ED

produce two apparent new frequen- ambient noise (40; 41) or headphones only (44; 44).

MJA 2011; 195: 694–698 cies — the sum and the difference of Conclusion: In moderately anxious ED patients, state anxiety was reduced

doi: 10.5694/mja10.10662 the original two sounds.5 This is an by 10%–15% following exposure to purpose-designed sound interventions.

auditory brainstem response to the Trial registration: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN

difference in amplitude of the origi- 12608000444381.

nal two tones. Binaural beat may

induce a meditation-like state and tal sound recordings with and without • sound compositions from audio

also reduce chronic anxiety.6 embedded binaural beat. field recordings of natural and con-

Only a few studies have explored structed settings;

the impact of music on anxiety in the • sound compositions from audio

Methods field recordings obtained from natural

ED setting. Music therapy has been

settings with embedded binaural beat;

shown to alleviate anxiety among • reconstructed ambient noise simu-

adults accompanying children to the Tool development

lating the ED but free of clear verbali-

ED,7 but not among adults undergo- Sound compositions were developed sations.

ing laceration repair.8 One pilot study in studios at RMIT University. Ambi- Use of specific sounds, instruments,

showed reduced pain9 among ED ent noise recordings, composition tempo, dynamics and timbre for both

patients, and others showed some testing, and the clinical study were the electroacoustic composition and

benefit on self-rated stress and noise conducted in the ED at St Vincent’s the audio field recordings were based

disturbance.10,11 No study has investi- Hospital, Melbourne (SVHM). SVHM on feedback from patients in the pre-

gated possible anxiolytic effects of is an adult tertiary referral hospital on liminary study, the composer’s aes-

The Medical Journal soundofinterventions

Australia ISSN:

or 0025-

binaural beat the fringe of the central business dis- thetic judgements and feedback from

729X 5/19 December 2011 195 11/12 694-698

among adult ED patients. trict of Melbourne, with about 40 000 fellow investigators. The electro-

©The Medical Journal of Australia 2011

www.mja.com.au We conducted a randomised con- ED attendances annually. acoustic musical composition used

Research trolled trial to investigate whether Using the results of a preliminary software-based electronic processing

emergency patients’ self-rated levels study to determine patients’ listening to transform a variety of sounds pro-

of anxiety were affected by exposure preferences (Box 1), four 20-minute duced by melodic and percussion

to purpose-designed musical compo- sound recordings were created: instruments. Audio field recordings

sitions and non-musical environmen- • electroacoustic musical composition; included sounds of bellbirds, cocka-

694 MJA 195 (11/12) · 5/19 December 2011

Research

1 Preliminary study

• no soundtrack intervention, head-

12

phones only (control group);

In a preliminary study, ten 60-second electroacoustic soundtracks, and ten 60-second

composed environmental soundtracks were created. For electroacoustic soundtracks, • reconstructed ambient noise sim-

decisions regarding the inclusion of sounds, instruments, tempo, dynamics and timbre were ulating ED noise but free of clear

based on the composer’s aesthetic judgements and feedback from fellow researchers — for verbalisations;

example, what they liked and what they found relaxing. Environmental soundtracks were

created, arranged and mixed to reflect the acoustic and spatial complexities of regional and • electroacoustic musical composi-

urban environments, including natural bush habitats, farms, city streets, the beach and tion;

factories. • composed non-musical audio

One hundred emergency department patients were recruited using convenience sampling. field recordings;

Patients aged 18 years or over were eligible if they presented between 9 am and 6 pm on

weekdays during the data collection period.

• combination of audio field record-

ings with embedded binaural beat.

The brief tracks were played to patients on iPods through headphones. The play order was

random. Participants were administered a purpose-designed survey about their usual

Participants were asked to listen to

listening preferences and their responses to the sound compositions (by rating the extent to the soundtrack through headphones

which each track evoked each of ten emotions). Before the patient listened to the tracks, the

researcher demonstrated use of the iPod, and participants were encouraged to pause

attached to an iPod. Soundtracks

between each track to answer the survey. ◆ were played through semi-open pro-

fessional headphones (AKG, k121

studio; Harman International, Stam-

toos, bullfrogs, green frogs, a glacial unable to give informed consent (eg, ford, Conn, USA). The headphones

stream, footsteps on snow, trees cognitively impaired or highly care- were covered with new disposable

blowing in the wind, water in a lake, dependent patients). No attempt was sanitary covers (SS-3-100; Scan

sailing-boat masts, crickets, and rain made to specifically recruit patients Sound Inc, Deerfield Beach, Fla, USA)

on a tin roof. who were anxious. for each listener. Headphones and

The binaural beat was embedded iPods were wiped with alcohol.

into the background of the audio field Main outcome measure Patients in the control group wore

recordings. We constructed binaural Patients’ anxiety levels were self- headphones attached to an iPod but

beat audio using two digital sine-tone reported as measured by the Spiel- did not hear a soundtrack. The

generators at 200 Hz and 210 Hz. To berger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory researcher recorded the duration of

alter the depth of the meditative state, (STAI),14 a 40-item self-report meas- listening or headphone wearing.

the interval between generators was ure containing 20 items measuring Medical and nursing assessment and

reduced by 2 Hz during the course of state anxiety (anxiety experienced at management took precedence over

the composition until a 4 Hz fre- that moment) and 20 measuring trait any study activity. The listening was

quency differential was achieved, anxiety (usual level of anxiety). Scores sometimes interrupted for treatment.

gradually increasing to 10 Hz over the for state and trait components each Staff were advised to carry on as nor-

final movement of the composition. range from 20 to 80, with a higher mal, interrupting patients if they nor-

To construct the ambient sound- score corresponding to higher anxiety. mally would do so. Regardless of the

track, the ED was analysed for key This scale is the most widely validated actual listening duration, the STAI

sounds to determine the range of anxiety scale.14,15 (state component) was readminis-

sounds occurring within daily opera- tered 20 minutes after the provision of

tion. Closed-field condenser micro- Procedure

the soundtracks, thereby keeping

phones captured specific noises such Between 1 February 2010 and 14 April exposure time consistent. Neither

as air conditioning, fluorescent lights, 2010, one of us (D M B) and another participants nor researchers were

telephones, computers, specialist researcher recruited participants blinded to allocation at the post-inter-

medical equipment, etc. This type of between 9 am and 6 pm on weekdays. vention assessment of outcomes.

microphone did not record anything Category 3 patients were identified We recorded participants’ receipt of

in close proximity (such as human using the ED administration system. analgesia before or during the study.

voices). Additional sounds generated After each patient was allocated to a Basic patient demographics (age, sex,

by staff, such as footsteps, were later cubicle, had an initial medical assess- country of birth, presenting com-

recreated in a studio. ment and gave consent he or she was plaint) were recorded to determine

given the STAI to self-administer whether the sample was representa-

Participants (state and trait components). We used tive of the broader population of cate-

Patients were eligible to participate if a computer-generated block-ran- gory 3 patients.

they were ⭓ 18 years of age and were domisation sequence (administered This study was approved by the

classified on arrival in the ED as cate- by a non-recruiting researcher). Par- Human Research Ethics Committee at

gory 3 according to the Australasian ticipan ts an d researchers w ere SVHM.

Triage Scale (ATS)13 — that is, patients blinded to allocation until interven-

with an acuity level indicating they tions were administered. Allocations Data analysis

required medical assessment within 30 were concealed using opaque paper, We analysed data using SPSS version

minutes. Participation was restricted to folded and stapled to data collection 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA)

these patients to maximise homo- instruments. Removal of the paper using an intention-to-treat approach.

geneity in the sample. Patients were revealed the allocation. Participants We used descriptive statistics includ-

excluded if they had a hearing impair- were allocated at random to one of ing frequencies, percentages, meas-

ment, did not speak English or were five groups: ures of central tendency and cross

MJA 195 (11/12) · 5/19 December 2011 695

Research

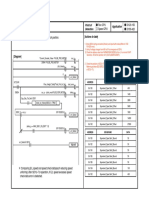

2 Recruitment, randomisation and retention of patients throughout the trial

Emergency department (ED) Excluded (n = 116)

patients assessed for eligibility • Non-cognisant: 11

(n = 291) • Refused consent: 84

• In isolation: 4

• Hearing impaired: 1

• Tested on previous visit: 2

• Unable to communicate in English: 14

Provided consent (n = 175)

Failed to complete baseline test (n = 5)

Completed baseline anxiety self-assessment

(n = 170)

Allocated to intervention (n = 170)

No soundtrack Reconstructed Electroacoustic Composed Composed

intervention, ambient noise musical non-musical non-musical

iPod and simulating an ED composition soundtracks derived soundtracks derived

headphones only (n = 34) (n = 34) from audio field from audio field

(control group) recordings recordings +

(n = 34) (n = 34) binaural beat

(n = 34)

• Interrupted during • Completed • Completed • Completed • Completed

intervention listening: 14 listening: 29 listening: 29 listening: 26

period: 18

Completed post-intervention anxiety self-assessment (n = 169)

• Withdrawals: 0

• Incomplete: 1, from electroacoustic composition intervention group

tabulations. Demographic data were detect a difference between means col; however, one patient did not

analysed using the Fisher exact test with a two-sided test at a 5% signifi- complete the post-intervention STAI.

for 2 2 cross-tabulations and the cance level, a sample size of 34 in each Those refusing consent did not differ

independent samples t-test for inter- group was required (assuming a dif- significantly from the sample in terms

val data. Preliminary analyses indi- ference in means of 13% and a com-

cated th ere was no significant mon standard deviation of 10%).

departure from normality. Therefore, 3 Comparison of participants with all

data were analysed using repeated patients attending the ED during

Results the study period and classified as

m eas ure s an aly sis of va ria nc e category 3 on the ATS

(ANOVA) to determine any change in Participation

anxiety from baseline within each Sample Eligible*

Between 1 February 2010 and 14 April Variable (n = 170) (n = 3117)

group. Univariate ANOVA was used

to compare levels of anxiety for each 2010, 291 category 3 patients in the Median age in 52 47

years (range) (35–69) (30–70)

group after accounting for baseline SVHM ED were considered for partic-

ipation in our study. Of those Men 93 1678

differences (using percentage differ- (no. [%]) (54.7%) (53.8%)

ence from baseline). No attempt was approached, 84 refused consent, 32

were considered ineligible and 175 Country of 110 (69%) 1818

made to adjust for multiple compari- birth Australia (58.3%)

sons. Alpha was set at 0.05. consented (Box 2). Five of those who (no. [%])

consented failed to complete baseline Abdominal Abdominal

Modal

Sample size calculation STAI and were withdrawn. The presenting pain pain

Our sample size estimate was based remaining 170 participants were complaint

on previous studies investigating bin- equally allocated to one of the five ATS = Australasian triage scale.

aural beat and anxiety using the interventions (34 per group). There ED = emergency department.

*2.9% required an interpreter. ◆

STAI.4,16 With power set at 90%, to were no violations of allocation proto-

696 MJA 195 (11/12) · 5/19 December 2011

Research

4 Presenting complaints of 5 Mean total state anxiety scores before allocation and after the intervention, and

participants (n = 170) number of participants requiring pain relief*

Presenting complaint No. (%) Total state anxiety,

mean (SEM)

Pain — abdominal 28 (16.5%)

Pain — chest 15 (8.8%) Absolute difference Participants

Pre Post from control† requiring pain

Shortness of breath 10 (5.9%) Intervention intervention intervention (95% CI) relief (no. [%])

Trauma 10 (5.9%) Control (headphones 43.7 (14.2) 43.7 (16.4) 27 (79.4%)

Collapse 7 (4.1%) only)

Headache 7 (4.1%) Simulated emergency 40.3 (11.6) 40.8 (11.5) 2.9 (- 2.28 to 8.57) 19 (55.9%)

department ambient

Pain — limb 7 (4.1%) noise

Pain — back 7 (4.1%) Electroacoustic 38.9 (11.5) 33.7 (7.8) 10 (1.9 to 12.9) 21 (61.8%)

Palpitations 6 (3.5%) musical composition

Pain — loin 5 (2.9%) Audio field recordings 42.2 (13.9) 34.6 (9.6) 9.1 (- 0.1 to 10.8) 27 (79.4%)

Seizure 4 (2.4%) Audio field recordings 42.6 (10.9) 36.9 (11.1) 6.8 (- 2.3 to 8.6) 27 (79.4%)

+ binaural beat

Weakness 4 (2.4%)

4 (2.4%) State anxiety score ranges: low or no anxiety, 20–37; moderate, 38–44; high, 45–80.17 * n = 34 for each

Pain other

group except electroacoustic composition (n = 33). † Based on post-intervention mean values. ◆

Other* 56 (32.9%)

* Represents 35 other presenting complaints

where n ⭐ 3. ◆ composition, composed audio field control group and the participants

recordings, or composed audio field who listened to simulated ED sounds

recordings + binaural beat reporting remained moderately anxious after

of age, sex, Australian country of significantly lower levels of anxiety the intervention.

birth, or modal presenting complaint. after the intervention compared with A previous study using music dur-

those in the control group and the ing laceration repair in a Pittsburgh

Demographics and clinical data group listening to simulated ED ED showed that listening was asso-

The demographic characteristics of the sound (Box 6). These effects were ciated with reduced pain but not

final sample were comparable to all unchanged after controlling for provi- reduced anxiety. 8 In that study, par-

other patients who would have been sion of pain relief. ticipants chose the artist and style of

eligible to participate based on ATS music. In contrast, our study used

code (Box 3). Sixty-nine percent (118) Trait anxiety highly original compositions devel-

of participants required pain relief dur- Mean trait anxiety did not differ sig- oped by experienced musicians and

ing their ED stay. No significant differ- nificantly between groups and ranged composers, and we did not record

ences were found between any groups from low to moderate (Box 7). particular anxiety-provoking activi-

in terms of age, sex or pain relief ties experienced by our patients,

required. Participants had a broad Discussion who received usual ED care and

range of presenting complaints (Box 4). procedures for category 3 patients.

Our study is the first randomised Such patients are typically quite

State anxiety controlled trial to show that sound unwell and undergo many investi-

There was a significant interaction compositions decrease anxiety in gations and procedures. Our results

effect between time and intervention adult ED patients. We showed that indicate that these patients gained

(F(4,164) = 6.28; P < 0.001), indicating a the baseline level of anxiety in considerable relief from anxiety by

change over time in some, but not all, patients in the mid range of urgency listening to sound compositions and

of the intervention groups. Pairwise in an Australian ED was moderate at raise the possibility that such origi-

comparison based on mean total state baseline. Mean normal state anxiety nal compositions are more effective

anxiety levels (Box 5) revealed a sig- scores have previously been reported in alleviating anxiety than simply

nificant decrease in anxiety (post- as 35.7 for men and 35.2 for women.19 listening to well known music. This

intervention mean compared with In our study, they ranged between s h ou ld b e e xplo re d in f utu re

pre-intervention mean) among par- 38.9 and 43.7 for the five groups, research.

ticipants listening to the electroacous- indicating moderate anxiety. Mean We found that binaural beat pro-

tic composition (P = 0.001), composed anxiety was significantly reduced vided no additional anxiety reduction

audio field recordings (P < 0.001), and among patients who listened to elec- over audio field recordings alone, in

composed audio field recordings + troacoustic music, audio field record- contrast with the 26% reduction in

binaural beat (P < 0.001). When com- ings or audio field recordings with preoperative anxiety observed else-

pared with each other, these same embedded binaural beat, to between where.4 This raises the possibility that

three groups showed no significant 33.7 and 36.9 — a level of no or low binaural beat is less effective in the

difference in post-intervention mean anxiety. The statistically significant busy ED environment than in the

level of anxiety. effect size of about 10%–15% was felt quiet preoperative area.

After accounting for baseline anxi- to be clinically significant as well. We As we had no previous experience

ety levels, significant differences were did not investigate whether the effect of applying binaural beat audio to

observed between groups, with those persisted beyond the post-interven- soundtracks, it is possible that this

allocated to receive the electroacoustic tion assessment or was transient. The intervention was not delivered appro-

MJA 195 (11/12) · 5/19 December 2011 697

Research

department care: perspectives of accompanying

6 Percentage difference in mean (SEM) state anxiety compared with baseline, by persons. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 3489-3497.

intervention group

2 Lelchuk Staricoff R. Arts in health: a review of the

medical literature. London: Arts Council England,

5%

2004.

3 Nilsson U. The anxiety- and pain-reducing effects

of music interventions: a systematic review.

AORN J 2008; 87: 780-807.

0 4 Padmanabhan R, Hildreth AJ, Laws D. A

prospective, randomised, controlled study

examining binaural beat audio and pre-operative

anxiety in patients undergoing general

State anxiety (% difference)

anaesthesia for day case surgery. Anaesthesia

−5%

2005; 60: 874-877.

5 Oster G. Auditory beats in the brain. Scientific

American 1978; 229: 94-102.

6 Le Scouarnec RP, Poirier RM, Owens JE, et al. Use

−10% ED ambient sound of binaural beat tapes for treatment of anxiety: a

Headphones only pilot study of tape preference and outcomes.

Electroacoustic composition Altern Ther Health Med 2001; 7: 58-63.

Audio field recordings + 7 Holm L, Fitzmaurice L. Emergency department

−15% binaural beat waiting room stress: can music or aromatherapy

Audio field recordings improve anxiety scores? Pediatr Emerg Care

2008; 24: 836-838.

8 Menegazzi JJ, Paris PM, Kersteen CH, et al. A

randomized, controlled trial of the use of music

−20% during laceration repair. Ann Emerg Med 1991; 20:

Pre intervention Post intervention

348-350.

Time 9 Tanabe P, Thomas R, Paice J, et al. The effect of

standard care, ibuprofen, and music on pain relief

ED = emergency department. Vertical bars represent SEM. P <0.05 significant. and patient satisfaction in adults with

Headphones only v composition, P = 0.024; headphones only v audio field recordings + binaural beat, musculoskeletal trauma. J Emerg Nurs 2001; 27:

P = 0.012; headphones only v audio field recordings, P 0.001. 124-131.

ED sound v composition, P = 0.004; ED sound v audio field recordings + binaural beat, P = 0.002;

10 Short A, Ahern N. Evaluation of a systematic

ED sound v audio field recordings, P 0.001. ◆

development process: relaxing musing for the

emergency department. Aust J Music Ther 2009;

priately, although we followed stand- length of the scale may limit its clini- 20: 3-26.

ard advice in programming. As we cal utility in the ED. Although a 6- 11 Short A, Ahern N, Holdgate A, et al. Using music

only tested these interventions on item short version of the STAI exists,20 to reduce noise stress for patients in the

emergency department: a pilot study. Music Med

ATS category 3 patients who had the validity in a broad range of clinical 2010; 2: 201-207.

received medical assessment in the samples was unknown at the time we 12 Macarow K, Brown D, Jelinek G. Art does matter:

ED, we cannot generalise our findings began the study. Nonetheless, only designing sound compositions for emergency

department patients [presentation]. Fifth

to all ED patients, including those five patients (2.9%) failed to complete International Conference on the Arts in Society;

with illness or injury of a different the pre-intervention STAI. 22–25 July 2010; Sydney, Australia. Urbana-

severity, or those who presented out- The use of randomised controlled Champaign, Ill: Common Ground Publishing.

13 Australasian College for Emergency Medicine.

side the hours of recruitment. It is trial methodology precluded allowing Policies and guidelines. P06: Australasian Triage

possible that patients requiring more patients to choose preferred or famil- Scale. Melbourne: ACEM, 2000. http://

urgent treatment, who are presum- iar sounds. Although sound prefer- www.acem.org.au/infocentre.aspx?docId=59

(accessed Nov 2010).

ably more anxious, might not derive ence and familiarity are important 14 Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al.

similar benefits. factors in the efficacy of sounds to State–trait anxiety inventory. Menlo Park, Calif:

A potential limitation of this study relieve anxiety,4 this has not always Mind Garden Inc, 1970.

15 Bieling PJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP. The state-

is the use of the STAI. At a total length been observed.8

trait anxiety inventory, trait version: structure and

of 40 items (20 state, 20 trait), the Our findings have important impli- content re-examined. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36:

cations for emergency medicine. 777-788.

7 Mean total trait anxiety scores, by Original sound compositions deliv- 16 Wang SM, Kulkarni L, Dolev J, Kain ZN. Music and

intervention group preoperative anxiety: a randomized, controlled

ered in EDs can significantly reduce study. Anesth Analg 2002; 94: 1489-1494.

Intervention group Mean (95% CI) the anxiety of patients waiting for 17 Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE, et al.

further management in this busy Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Control 35.61 Palo Alto, Calif: Consulting Psychologists Press,

(headphones only) (31.87–39.35) environment. 1983.

Reconstructed 39.72 18 Jezova D, Makatsori A, Duncko R, et al. High trait

emergency department (36.04–43.40) Acknowledgements: This study was supported by the anxiety in healthy subjects is associated with low

ambient sound Australian Research Council Linkage Project’s funding neuroendocrine activity during psychosocial

scheme (project number LP0882346), project title,

Electroacoustic musical 36.96

stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol

“Designing sound for health and wellbeing”. David Brown

composition (33.28–40.64) Psychiatry 2004; 28: 1331-1336.

received support in the form of research assistance from

St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne. We acknowledge the 19 Ruffinengo C, Versino E, Renga G. Effectiveness of

Audio field recordings 39.99 an informative video on reducing anxiety levels in

work of the late Associate Professor Andrew Dent who

(36.31–43.67)

was instrumental in the development of this study. patients undergoing elective coronarography: an

Audio field recordings 40.43 Competing interests: No relevant disclosures. RCT. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2009; 8: 57-61.

+ binaural beat (36.75–44.11) 20 Tluczek A, Henriques JB, Brown RL. Support for

Received 24 Jun 2010, accepted 30 Nov 2010.

the reliability and validity of a six-item state

Trait anxiety score ranges: low, < 39; moderate,

1 Ekwall A, Gerdtz M, Manias E. Anxiety as a factor anxiety scale derived from the state-trait anxiety

39–45; high, > 45.18 ◆

influencing satisfaction with emergency inventory. J Nurs Meas 2009; 17: 19-28. ❏

698 MJA 195 (11/12) · 5/19 December 2011

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- New Zealand Football National Leagues System ProposalDocument6 pagesNew Zealand Football National Leagues System ProposalStuff NewsroomNo ratings yet

- Quantum Cosmology and Baby Universes TQW - DarksidergDocument365 pagesQuantum Cosmology and Baby Universes TQW - DarksidergGhufranAhmedHashmi100% (2)

- Manual de Instalação PSCBR-C-100Document214 pagesManual de Instalação PSCBR-C-100danielwjunior100% (2)

- ProblemDocument11 pagesProblemMaximino Eduardo SibayanNo ratings yet

- TM 9 2320 280 20 2Document954 pagesTM 9 2320 280 20 2Angel Torres100% (2)

- EMC NetWorker Fundamentals - Course Description PDFDocument2 pagesEMC NetWorker Fundamentals - Course Description PDFmoinkhan31No ratings yet

- 2158-2017 05 IEEE YP Loke FinFETDocument29 pages2158-2017 05 IEEE YP Loke FinFETAditya MadhusudhanNo ratings yet

- Airline Reservation SystemDocument81 pagesAirline Reservation SystemBanagiri AkhilNo ratings yet

- Assessment On The Preparation of The Department of Education On The First Year of Implementation of The Senior High School Program.Document20 pagesAssessment On The Preparation of The Department of Education On The First Year of Implementation of The Senior High School Program.Veron GarciaNo ratings yet

- Design of Pile Cap ExampleDocument11 pagesDesign of Pile Cap ExampleNikhilVasistaNo ratings yet

- Powerapps Design TemplatesDocument17 pagesPowerapps Design TemplatesMarino AbreuNo ratings yet

- Question of Smart AgricultureDocument3 pagesQuestion of Smart AgricultureEmtronik ClassNo ratings yet

- Turcon Varilip PDR: Trelleborg Se Aling SolutionsDocument41 pagesTurcon Varilip PDR: Trelleborg Se Aling SolutionsaceinsteinNo ratings yet

- Marble Granite Selection Check ListDocument5 pagesMarble Granite Selection Check Listvahab_shaikNo ratings yet

- Plan Child Bank Statement Year001Document7 pagesPlan Child Bank Statement Year001Naima AbdulrahmanNo ratings yet

- Group 4 - HandoutDocument17 pagesGroup 4 - HandoutKyle Justin RayosNo ratings yet

- Presentation PosterDocument1 pagePresentation PosterMihir PatelNo ratings yet

- SAP BPC Consultant A Leading MNCDocument3 pagesSAP BPC Consultant A Leading MNCSathish SarupuriNo ratings yet

- Let Us Know Who You Are: Guest Details 1 Payment 2 ConfirmationDocument3 pagesLet Us Know Who You Are: Guest Details 1 Payment 2 ConfirmationFahrudin AlkhemiNo ratings yet

- How To Destroy Reading Comprehension Passages by RhymeDocument10 pagesHow To Destroy Reading Comprehension Passages by RhymeyaaarNo ratings yet

- Model LG LifeGuard Safety HoseDocument1 pageModel LG LifeGuard Safety HoseAbdullah FazilNo ratings yet

- 50 SoundDocument4 pages50 SoundKer QiNo ratings yet

- Erased Log by SosDocument3 pagesErased Log by SosJeremy LuriciNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Theories of HumorDocument5 pagesLinguistic Theories of HumorNilmalvila Blue Lilies PondNo ratings yet

- Holiday Homework (Summer 2015) - Maths-S-IB HL FormDocument5 pagesHoliday Homework (Summer 2015) - Maths-S-IB HL Formatharva234No ratings yet

- Ffective Riting Kills: Training & Discussion OnDocument37 pagesFfective Riting Kills: Training & Discussion OnKasi ReddyNo ratings yet

- Tpde QB PDFDocument11 pagesTpde QB PDFvignanarajNo ratings yet

- lp33 User ManualDocument94 pageslp33 User ManualAndrew SisonNo ratings yet

- Sd3 (U) Over Speed: Application Point of DetectionDocument1 pageSd3 (U) Over Speed: Application Point of DetectionAce Noah SomintacNo ratings yet

- Chromecore 434N-S: Technical Data SheetDocument1 pageChromecore 434N-S: Technical Data Sheetdneprmt1No ratings yet