Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Russian Empire's Religious Policy in Georgia (The First Half of The 19th Century)

The Russian Empire's Religious Policy in Georgia (The First Half of The 19th Century)

Uploaded by

Andrei Si Evelina InsurataluOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Russian Empire's Religious Policy in Georgia (The First Half of The 19th Century)

The Russian Empire's Religious Policy in Georgia (The First Half of The 19th Century)

Uploaded by

Andrei Si Evelina InsurataluCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/299034300

The Russian empire's religious policy in Georgia (the first half of the 19th

century)

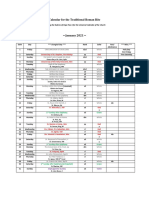

Chapter · January 2014

CITATIONS READS

0 60

1 author:

Khatuna Kokrashvili

Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

2 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Certain Aspects of Georgia-Russian Relations in Modern Historiography, David Muskhelishvili Editor, Caucasus Region Political, Economic and Security Issues, Nova

Publishers, New York, 2014. View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Khatuna Kokrashvili on 16 February 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

CAUCASUS REGION POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, AND SECURITY ISSUES

CERTAIN ASPECTS

OF GEORGIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS

IN MODERN HISTORIOGRAPHY

DAVID MUSKHELISHVILI

EDITOR

New York

Complimentary Contributor Copy

In: Certain Aspects of Georgian-Russian Relations ISBN: 978-1-63321-921-2

Editor: David Muskhelishvili © 2014 Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Chapter 6

THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE’S RELIGIOUS POLICY IN

GEORGIA (THE FIRST HALF OF THE 19TH CENTURY)

Khatuna Kokrashvili*

Institute of History at Ivane Javakhishvili University, Georgia

From the history of the Russian Georgian religious relations, in the second half of the 18th

century after the anti-Osman expedition ended successfully, Russia, according to the

Kuchuck-Kainarji peace treaty, was declared to be a defender of all eastern Christians. [1]

Hence by means of this international document, the historical ambition of the Russian empire

connected with the main idea of the Russian messiahship was officially formed. According to

this idea, born as early as in the 15th century, after the collapse of Constantinople, Moscow

was recognized as the centre of the Christian East, i.e., the ―third Rome;‖ as for the whole of

Russia, she was given the function of defender and spreader of the Orthodox Christian faith

and as successor to the Byzantine empire. According to the regulation of the 23rd article of the

Kuchuck-Kainarji peace treaty, Russia officially confirmed an important advantage for

herself in the whole of the Christian East including in the Transcaucasian region, in countries

already conquered by her, and also those she intended to conquer in future; defending the

Orthodox faith became an indivisible part of Russia‘s colonial policy; the idea of expanding

the empire‘s frontiers was interpreted as a sacred mission, entrusted to her from above, i.e., by

God Himself, besides, she was justified by spreading, defending and protecting Orthodox

Christianity within the limits of the mentioned territories.

During the whole of the 18th century the relations in the church and religious sphere also

acquired a specific character alongside the political relations of Russia and Georgia. It is

noteworthy that there was quite a large number of ecclesiastics in Russian cities and

theological centres who had come to Russia from Georgia to receive education or who had

actively found work in various places of the empire. Moreover some were entrusted with

managing independent church chairs in Russia. In this connection it is sufficient to remember

the names of the following Georgian ecclesiastics: the Georgian catholicos-patriarch, Anton I,

who was head of the archbishop‘s chair in the town of Vladimir; Archbishop Ioseb Samebeli;

the archimandrite of Yuriev monastery; Bishop Ioann Mangleli archimandrite of Znamenski

*

Main Scientific Worker/Corresponding author: E-mail: kh.kokrashvli@gmail.com.

Complimentary Contributor Copy

64 Khatuna Kokrashvili

monastery in Moscow; Gaioz Baratashvili, a graduate of the Moscow Theological seminary,

later bishop of Mozdok, and still later bishop of Astrakhan. It should be noted that the latter

successfully led the Russian-Georgian ecclesiastic mission of spreading the Orthodox faith

among the Caucasian mountain peoples. [2] Thus the ecclesiastical authorities of the Russian

empire did their best to find active and trustworthy supporters of the idea of Russian Georgian

unity, among a selected part of the Georgian ecclesiastics.

Russia skillfully used the pro-Russian orientation of the Georgian kings to occupy the

dominating position in the Caucasian region: it was the critical moment and carried out by the

Georgian kings that mainly defined the course in the Russian direction. At the end of the 18th

century beyond any doubt, ―the coreligious factor‖ was one of the most important factors that

determined Georgia‘s historical choice towards Russia in the many centuries long fight

against Islamic world-orientation. [3]

It is noteworthy that the historiography of the Georgian church from the very beginning

especially accentuated the phenomenon of coreligiousness as its ideological basis. Georgia,

finding itself in a hopeless situation, with the help of this ideological basis started its relations

with Russia.[4] Academician I. Javakishvili also mentioned the great significance of the

factor of faith. He showed that the Russian authorities, as well as diplomatic establishments

profitably used this factor in their military and political interests, while Georgia, hoping to be

protected by the coreligious empire, was a loser, as a rule.

The terms, stipulated in the 8th article of the Georgievski Treaty concluded between

Russia and Georgia in 1783 seemed quite unacceptable for the autocephalous status of the

Georgian Orthodox Christian church. The 8th article defined the Georgian-Russian

interrelations in the sphere of the church; the Catholicos-Patriarch of the Georgian Orthodox

Christian Church was declared to be a member of the Russian Holy Synod, and occupied the

8th place in the Russian ecclesiastical hierarchy. In an urgent situation it was envisioned to

work out an additional article which would be able to regulate the forms of governing the

Georgian Orthodox Christian Church and settling its relations with Russia. [5] However, such

an article was not worked out; consequently, the management and the regulations of the

Georgian church remained unchanged at the given stage. It is noteworthy that the equalization

of the title of the catholicos-patriarch with ordinary rank and file members of the Holy Synod

hierarchically, as well as the attempts of the secular authorities to establish the main

principles of managing for the autocephalous Georgian church, was unjustified according to

all the laws and norms of church law. [6] All this indicated quite definitely the

insurmountable desire of the Holy Ruling Synod to subject the Georgian autocephalous

church to its influence at any cost gradually, step by step, to humiliate it and to diminish its

hierarchical status and self-consciousness.

The relations between Russia and Georgia at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries are

assessed in Georgian historiography as the manifestation of naivete on the part of the Kartli-

Kakheti authorities and their superfluous, ―inexhaustible‖ trust of Russia, founded mainly on

―coreligiousness.‖ Owing to such a policy, the development of processes ended in the well-

known manifesto of 1801 which was followed by the abolition of the Kartli-Kakheti kingdom

and the factual annexation of Georgia. [7] The same act played a decisive role in the solution

of the fate of the Georgian church.

It must be noted here as well that irrespective of coreligiousness and common faith with

Russia, the Georgian Orthodox Christian Church found itself face to face with the Russian

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 65

church, fundamentally different from it by its structure. The last circumstance determined the

character of the church policy of Russia in Georgia to a significant extent.

The church reform, carried out by Peter I in 1722, set the beginning to a new, so called

‗synod period‘ of the development of the Orthodox church in Russia. The result was the

abolition of the institute of patriarchs and the establishment of a permanently acting council

(synod) of high hierarchs the Holy Ruling Synod. The cultural-legal forms and principles of

church management were fundamentally changed. According to the ecclesiastical regulations,

the monarch was declared to be the highest ruler of the church and consequently,

representatives of the clergy took an oath of allegiance to the monarch and the dynasty, and

not to church dogmas. With the aim of guaranteeing a corresponding status to the Holy

Synod, the latter was declared to be a governmental organ, i.e., an establishment, having state

power like the Senate. The result of the reform was that the reins of government of the church

factually turned out to be in the hands of the state power; Russia‘s emperor himself governed

the affairs of the church through the Holy Synod.

The position of an over-procurator was established with the purpose of the permanent

control of the Holy Synod. At the beginning, the competence of the over-procurator was

compiling reports to the emperor and writing annual accounts for the Synod. As time went on

the circle of his duties extended and he was charged with governing the establishments and

departments of the Synod: the chancellery, economy, the teaching committee, printing-house,

etc. The over-procurator had the main position in the secretariat of the Holy Ruling Synod,

and this in its turn conditioned the further strengthening of this institution and the local

extension of its duties. However paradoxical as it may seem, the essentially non-canonical

character of the church reform of Peter I was officially recognized by the Constantinople and

Antioch patriarchs. [8]

The use of church lands in the interests of the state seemed to be quite a characteristic

phenomenon for church reforms carried out in Russia. This process was finished in the 18th

century when in 1874 all movable and immovable property of the church was declared to be

the property of the state. [9] I.e., all the rights of the control, exploitation and the disposal of

incomes turned out to be the prerogative of the state. A salary was paid to representatives of

the clergy, thus turning them into state officials.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the power of the monarchy in Russia became

absolute; all the segments found in the country were subjected to state and emperor as much

as possible. The process of the formation of capitalist relations was accompanied by definite

changes in the social and economic life of the Russian empire; these, fundamental

circumstances of their kind, determined the absolutely new relations between the state and the

church.

At the beginning of the 19th century the relations between the church and the state in

Russia stepped into quite a new phase. If the state power managed in the 18th century to halt

and put to an end to the political independence of the church, in the first half of the 19th

century the process of managing the affairs of the church appeared in the hands of secular

bureaucratic officials. In 1802 on the initiative of Alexander I the Holy Synod was deprived

of the right of any direct communication with state establishments: from that time on such

relations were realized through the over-procurator; consequently, the power of the latter

became higher: besides the power that he already had, he was also given the functions of

guiding and managing. [11]

Complimentary Contributor Copy

66 Khatuna Kokrashvili

The expansion of the territories of the empire in all directions at the expense of adjoining

regions, settlements inhabited by representatives of different nationalities and different

religions significantly influenced the general condition of the Russian Orthodox Christian

Church. It is quite natural that a question, corresponding to the state interest, was raised about

relations with various religious trends and beliefs. The existence and development of different

religions inside an empire were to be subjected to the following ideological formula

―Orthodox, Autocracy and Nationalism.‖ Consequently, all efforts were directed so that

Orthodox Christianity should preserve its position as leader so that it could fullfill, the

function of a state religion with its legal status, clearly determined by the state legislation.

It is quite natural that in conditions when absolute monarchy flourishes, Russian power

could not bear the existence of an independent self-governing church organization in Georgia.

In 1801 Eastern Georgia became a gubernia of the Romanov empire, having no rights. After

the Kartli-Kakheti kingdom was joined to Russia, the process began of transforming the

Georgian Orthodox Christian church in the Russian manner.

The interrelations between the Georgian church and the Georgian state were historically

built on the following principle: full freedom and no pressure in the matter of spreading the

Christian faith; full independence of the church ways of life and its internal management,

non-interference by secular authorities in the competence of the high hierarchs of the church;

the inviolability of church property. However, when the new epoch set in, the reorganization

of the Georgian Orthodox Christian church was turned in a diametrically opposite direction.

[12]

The Russian emperor, Paul I from the very beginning declared the following in his

highest rescript to General Knorring: ―I want Georgia to be a gubernia as I have already

written to you and so connect it with the Senate; as for the church connect it with the Synod,

without touching upon their privileges. Let the governor be someone of royal blood, but he

will be under you and the chief of the new regiment of hussars.‖ [13] At the same time the

Holy Synod revealed a special gift for initiatives with the same kind of declarations to

establish the exact number of eparchies and monasteries on the territory of Eastern Georgia,

about the availability of the organs of church courts of law, about the preparation of the

personnel of the clergy, and finally about the theological schools and church incomes. [14]

All this doubtlessly pointed to the fact that together with joining Georgia to Russia there was

a plan for reorganizing the Georgian Orthodox Christian church: it was planned to form the

Tbilisi (Kartli) eparchy and the Telavi (Kakheti) eparchy; in each of them dicasteries should

be established, and in the other towns of the country – ecclesiastical management. In addition

they intended to introduce the position of an auditor in the Tbilisi eparchy, eparchy of Gori.

[15]

After the demise of Paul I the Georgian envoys presented a note to the Russian

government. They formulated the following requests, concerning the question of the church:

non-interference in the internal affairs of the Georgian Orthodox Christian church, preserving

the title and order of the Catholicos-Patriarch, Anton II, and to all ecclesiastics in the

Georgian eparchies.

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 67

The abolition of the autocephaly and Russia’s church reform in Georgia

According to the manifesto of September 12, 1801 the Georgian clergy were promised

the inviolability of the privileges they had, free performance of religious rites and a

guaranteed right to church property. [16] As a matter of fact, the manifesto recognized and

affirmed the independence and inviolability of the Georgian church. Besides, the religious

symbols connected with Georgia obtained special significance. Alexander I expressed his

wish to return to the Georgians St. Nino‘s cross, made of vine, the Georgian people‘s

centuries long sacred relic, as a sign of favour. In this case it was extremely noteworthy that

this sacred cross was at the head of the Russian troops when they first stepped on the territory

of Georgia.

However, it is universally known that the Russian authorities were always distinguished

by their short memory: they permitted Anton II to preserve his title, but his competence was

restricted. Moreover, many cases are registered of the violation of the rights of the Georgian

Orthodox Christian church and of the clumsy interference on the part of the Russian officials

in the functions of the archpriests Knorring, Lazarev, Tsitsianov and others were the ones at

fault. The latter actively interfered in the internal affairs of the church, demanding materials,

connected with church property, and also demanding data, reflecting all income and

expenditure. Apart from that, they voluntarily and without agreeing with anybody, planned to

reduce the number of eparchies and the clergy and demanded that the Catholicos-Patriarch

should not take any decision without permission of the political authorities, etc. [17]

As soon as he assumed office, commander in chief General Tormasov began to take

important steps with the purpose of the structural and administrative reorganization of the

Georgian Orthodox Christian Church. At the beginning in order to avoid mass discontent the

imperial government intended to use local Georgian personnel while carrying out the reform.

With this purpose in mind, Catholicos-Patriarch, Anton II, was offered to draw up a project

for the reorganization of the Georgian church. Anton II agreed to carry out a reform on

condition that the independence of the Georgian church was preserved. However, the reform,

planned by the Russian imperial government, in its essence implied including the Georgian

Orthodox Christian Church into Russia‘s church system and its complete merging with it.

This, in its turn, was only possible if the autocephaly of the Georgian church was abolished. It

is not surprising that proceeding from this, the request of the Georgian patriarch, already

mentioned, turned out to beunacceptable to the Russian party.

With the purpose of registering the number of churches and monasteries existing on the

territory of Georgia, and also to define with approximate precision, the number of the

ecclesiastics, the commander-in-chief Tormasov raised a question before the over-procurator

of the Synod in 1809 regarding the establishment of a theological dicastery as the high

ecclesiastical organ of management. Supposedly the new organ was to be headed by the

Catholicos of Georgia, and Varlaam Eristavi was prepared for the role of his assistant.

Varlaam Eristavi was Georgian by origin, brought up in Russia and well-versed in questions

of the management of Russian churches. But this initiative according to the plan prepared

beforehand, was not realized, for Anton II was summoned to Russia, to Petersburg, by the

will of Emperor Alexander I. Obeying the will of the emperor, the Catholicos-Patriarch of

Georgia departed to Petersburg on November 3rd, 1810. [18]

It should be noted that as early as from 1805, according to the emperor‘s wish, under the

pretext of becoming acquainted with representatives of the high clergy and the arrangement

Complimentary Contributor Copy

68 Khatuna Kokrashvili

of the church clerical work, there was the custom in Russia to invite ecclesiastics to

Petersburg, at the expense of the state and with the right to attend the sittings of the Holy

Synod. Candidatures of the persons to be invited were chosen after undergoing a thorough

selection. Besides, as a rule, the wish of the emperor to get acquainted with the high

representatives of the clergy personally very often was used for political aims: for instance,

the new order enabled the over-procurator, Golitsin, to take advantage of the occasion and

while the head of the eparchy was visiting the emperor, to completely carry out the planned

reforms, corresponding to the new system. [19]

So as it seems it was not a fortuitous decision at all, taken by the emperor, concerning

―the invitation‖ of Anton II to Russia: by the time the Georgian Catholicos-Patriarch arrived

in Petersburg the rescript of Emperor Alexander I would have already been prepared, in it the

aims of the government were indicated quite distinctly, namely as follows: ―After the

Georgian kingdom was joined to Russia the Georgian church had to obey the rules of

management of the Holy Synod for the presence of the Catholicos-Patriarch in Georgia would

not be compatible with the new system of the church.‖ [20]. In exchange for the voluntary

rejection of the throne of the archpriest the emperor promised Anton II to preserve all his

advantages, existing in the ecclesiastical sphere, among them a permanent seat in the Holy

Synod. In spite of a decided protest of the Georgian Catholicos-Patriarch, he was removed

from the Georgian church and was forced to leave Russia by a state decree.

The Russian church reform, carried out in Georgia in the first half of the 19th century,

developed in several directions: it implied a radical structural-administrative reorganization of

the Georgian church, the commutation of the church taxes and secularization of the church

lands: besides, it was envisioned to transform the order of the church service, the condition of

the lowest strata of the clergy and the system of theological education.

It was Varlaam Eristavi who was charged with the work on the project of the

reorganization of the Georgian church. The project, presented by him, was signed and

confirmed by the emperor on June 30, 1811. [21] The first stage of the reform of the church

was also connected with this project: the autocephaly of the Georgian church was abolished;

the Georgian exarchate was established instead of the patriarchy. The exarchate in fact was

subjected to the governing Holy All-Russian Synod). The first exarch of Georgia was

Varlaam Eristavi. The number of eparchies diminished substantially – instead of 13 eparchies,

existing in Eastern Georgia only two were formed: Mtskheta for Kartli and Alaverdi in

Kakheti; a dicastery was established for the clerical work of both eparchies. It was a special

organ whose chairman was Georgia‘s exarch. It was a special ecclesiastical management for

guiding the ecclesiastical affairs of Kartli and Kakheti, substituted later by the Synodal

Office. The functions of the dicastery were to study the situation in churches and monasteries,

to impose church taxes, to calculate and register the income of churches, to study divorces

and to regulate disputable problems or lawsuits, arising between ecclesiastics.

Since that time it was the exarch who was head of the Georgian Orthodox Christian

Church instead of a Catholicos-Patriarch. In a hierarchical sense it was the eccleasistical

degree between a metropolitan and patriarch. Apart from that the exarch was given an

advantageous right to occupy a permanent fourth place in the governing Holy Synod. To tell

the truth, not a single bishop had such a high title; however in reality Georgia‘s exarch had

fewer privileges in comparison with the rest of its members, viz. in many respects his rights

were more limited than, for instance, the rights of other eparchies inside Russia. [22]

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 69

A new era of church management set in the history of the Georgian church with the

establishment of the exarchate. It is true that the Russian power abolished the autocephaly of

the Georgian Orthodox Christian Church which then directly became subordinated to the

Holy Synod. At the same time a church organization was established that was allowed to

exercise all-round state control over the Georgian church and to give priority to the interests

of the empire.

The second stage of the reorganizing the Georgian church ended in 1814 viz. after the

abolition of the catholicate in Western Georgia, and according to the project drawn up by

Archbishop Dosytheos Pitskhelauri. Its result was that the church governing organs of Eastern

Georgia, the Imereti kingdom, and also of the principalities of Samegrelo and Guria were

united in the Georgian exarchate. On May 8, 1815 a Georgian-Imeretian Synodal office was

established instead of the ecclesiastical dicasstery. According to the definition of the Holy

Synod, Eastern Georgia was to have three eparchies instead of two the Mtskheta eparchy,

Telavi eparchy and Sighnagi eparchy. It was the same Dosytheos Pitskhelauri who was made

head of the Sighnagi eparchy. He was also appointed head of the recently restored ―Ossetian

ecclesiastical commission.‖ According to the high decree of August 30, 1814 Dosytheos

Pitskhelauri was appointed Telavi and Georgian-Caucasian archbishop,‖ giving him the

Ossetian Commission to guide and govern.‖ Due to the new regulation received by the

Synod, an ecclesiastical dicastery was to be established in Western Georgia in the city of

Kutaisi, however, owing to a very critical political situation created there, the dicastery was

not established after all, and instead ―an eparchial chancellery was to be established.‖ [23]

Soon the ecclesiastical power of the Russian empire considered Varlaam Eristavi and

Dosytheos Pitskhelauri to be unreliable officials for the state. In 1817 Ryazan‘s Bishop

Feofilakt Rusanov was sent to Georgia with a special mission. He was told to finish the

structural-administrative reform that had begun there. The latter started doing what he was

charged with, in the very first days he ordered that the service in Sioni cathedral should be

held in the Russian language three times a week. [24] Apart from that, immediately after his

arrival he presented a project for the reorganization of the exarchate, approved and signed by

the emperor on December 28, 1818. [25] The changes introduced into the system of

governing the church according to this project is assessed as the third stage of reorganization

in modern Georgian church historiography, [26] viz. according to Feofilakt Rusanov‘s

project, Eastern Georgian i.e., Kartli and Kakheti eparchies were united and received a new

name, a ―Kartli-Kakheti or Georgian eparchy,‖ as for Western Georgia, eparches with names

coinciding with the name of the region were formed, for instance, Imereti, Guria and

Samegrelo eparchies. The new reform envisioned a substantial staff reduction in churches, the

substitution of the duty, paid in kind for church tax, etc. However, the projected measures

caused a strong protest in the whole of Western Georgia: rebellion started in Imereti, then

embraced Guria, Samegrelo and Racha. ―The church riot‖ was suppressed with particular

cruelty. The bishops of the Imereti eparchy Euthymius of Gaenati and Dosytheos Kutateli

were punished with special severity.

Due to the very complicated situation created in connection with the rebellion of 1819-

1820, carrying out the reform in Western Georgia was stopped. In spite of the cruel measures

used while suppressing the rebellion, and the efforts made by the imperial power, they could

not complete the process of the reorganization of the church in Western Georgia during the

whole of the first half of the 19th century.

Complimentary Contributor Copy

70 Khatuna Kokrashvili

Besides the structural-administrative reorganization, the reform envisaged the exhaustive

calculation of the amount of property and all the income of the Georgian Orthodox Christian

church. It is noteworthy that as for the governing of the property, the Georgian church was

essentially different from that of Russia: in the first case the main source of income was

donations, among them being estates with serfs; consequently the Georgian Orthodox

Christian Church possessed quite a considerable amount of property; as for Russia, as early as

in the epoch of Catherine II church property was already in the hands of the state exchequer,

and representatives of the clergy, appointed by the state received salaries. The result of such

measures was that the Russian church had lost its initial, and it must be supposed its main,

functions; finding itself depending on the state financially, representatives of Russia‘s clergy

turned, as has already been mentioned, into ordinary officials carrying out Russia‘s imperial

policy.

From the point of view of using church property, the reform to be carried out in Georgia,

as we know, besides the commutation of the church taxes i.e., substituting paying in kind by

paying rent in money, also envisaged the secularization of the church lands i.e., giving the

church immovable property to the state exchequer. It is quite natural that all this process was

directed against the nationalization of the economic basis of the Georgian Orthodox Christian

church, as well as the appropriating of church revenue. It should be noted that from the point

of view of using its own property, the Georgian church found itself in a very unpleasant

situation in the first half of the 19th century. Church historiography confirms many cases of

stealing or appropriating church lands together with serfs, evading the paying of taxes and

other violations, needing regulating by the state. [27] With the help of the ecclesiastical

dicastery, the Georgian-Imeretian Synodal Office, and also the office calculations, organized

within the first half of the 19th century, it was managed to establish the approximate number

of church serfs and define the amount of their income. In 1818 the imperial power confirmed

the new staff time-table, by this defining the number of churches in the country and the ones

who served there. The same document regulated the number of parishes: each 80-100 yards

formed a parish.

By the beginning of the 19th century the following taxes were collected from the church

for church lands sursati, makhta, gala and kulukhi and for church parishes drama and

sakhutso, i.e., the tax, paid to the priest. The church peasants had the duty of working.

Besides all this only the church peasants or all the congregation paid money too for

performing various rites such as confession, eucharist, christening, wedding ceremonies, etc.

And still the main part of the taxes was paid in kind. Georgia‘s exarch Feofilakt Rusanov

realized the commutation of the church taxes; its result was that the amount of rent

considerably rose in the church taxes and beginning with the 1840s it occupied the leading

place in the payments made by church peasants.

The result of such measures was that the sum of money raised was transferred to the

exchequer; consequently the income of the state increased considerably. [28]

As for the secularization, i.e., turning church land into state property, this process had

several stages 1) 1811-1841 the church nobility with their estates and serfs were ascribed to

the fiscal department; 2) between 1842 and 1853 began the a process of transferring the

church lands to the state fiscal department; 3) between 1853 and 1869 all the church lands,

inhabited or uninhabited, were given to the state fiscal department for eternal possession.

The process of turning the church lands into state property ended in Kartli and Kakheti in

1869, in Imereti and Guria in 1871 and in Samegrelo in 1880. From then on the church

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 71

peasants became equal in their rights to the state peasants. An annual monetary income was

appointed to the ecclesiastical department, and the clergy received a salary from the state

exchequer, i.e., like the servants of the Russian Orthodox Christian church they became

ordinary state officials. In this way the Georgian church lost the main source of its income. In

the second half of the 19th century all kinds of church landownership factually disappeared in

Georgia, as well as church peasants, they were placed at the disposal of the fiscal department.

The duties of the clergy in the Russian empire were strictly defined and assigned, with

the agreements still in force according to the regulations of 1721: the clergy undertook the

obligation ―to be a faithful, kind and obedient slave and loyal to the emperor. Besides the

clergy were to tell the respective organs ―about all the damage, harm and loss of interest of

the imperial power.‖ Moreover the ecclesiastic had to undertake the obligation to violate the

secrecy of the confession and to report on all kinds of possible or supposed cases of ―theft,

treason or rebellion against the monarch.‖ The first duty of the clergy before the state was the

inculcation of loyal feelings among the Orthodox population. In this respect they at first tried

to succeed with the help of instilling the cult of the emperor‘s power. Such a policy found its

reflection in the history of Russia in the 18th century, viz. in the attempts to idolise and the

apotheosis of the emperor‘s person: e.g., it was admitted and encouraged to present the

reigning persons in church painting. However such attempts failed to gain popularity. When

the 19th century set in, the process of instilling the cult was resumed with new intensity and

this time developed in a different direction, i.e., in the form of the so called table or ―Tsar‘s

days;‖ the divine service was accompanied by special services, acathistos and canons, by

mentioning the names of the emperor and different members of his family. In the 19th century

this tradition acquired the status of an officially established rule, preserved up to the very

collapse of the empire in 1917. It is noteworthy that the fulfillment of this tradition, i.e., of the

carrying out of this festive divine service was more strictly watched than, let us say the

holding of any of the other festive church services.[30] Archive documents confirm that

eparchies and parish churches in Georgia received instructions in advance, concerning such

significant festivities and the offering of special prayers. On such days offering the liturgy for

the good of Russia‘s royal family became an inevitable condition for all acting churches and

monasteries on the territory of Georgia.

The tradition of the divine service underwent certain changes: according to the new order,

the service in churches and monasteries was carried out according to Slav church regulation.

In ethnically mixed parishes, the vespers were chanted in Russian, and in Georgian parishes

in Georgian. To instill Slav-Russian singing in Orthodox Christian churches, and also to

improve the technique of singing, a number of measures were taken throughout the empire: in

1804 the Holy State Synod required the performing of hymns, published exclusively in music

notation between 1815 and 1856 and were the only hymns permitted to be sung in churches.

It was forbidden to use hymns not approved by the director of the State Choir Turchaninov.

[31] In this way, as time went on, Georgian church chants were performed more and more

seldom, the musical scale was laid down.

Being unable to properly appreciate the beauty and refinement of the harmony of

Georgian church singing, the Russian officials treated the centuries long traditions of

Georgian hymnography with extreme disrespect. The commander-in-chief, P. Tsitsianov in

his so called ―letter‖ of March 25, 1804, to the Georgian Catholicos-Patriarch, Anton II,

demonstrates a good example of this. In this letter he, Tsitsianov, allowed himself in a more

than an insolent form to tell the head of the Georgian Orthodox Christian church of the

Complimentary Contributor Copy

72 Khatuna Kokrashvili

superiority of Slav singing. ―As many times I have heard it i.e., the Georgian church singing,

in churches here, they sound like a goat‘s bleating and if Your Holiness will wish to order to

teach the Kiev note by translating all the hymns into the Russian language?‖ [32] The exarch

Feofilact Rusanov‘s attitude towards Georgian church singing was also just as disrespectful:

in the Tbilisi theological school he established a class for exclusively studying Slav church

singing. And as it turned out some time later, again by his order, the singing lessons were

annulled. [33] Nevertheless, it should be noted that there were real appraisers and admirers of

the Georgian church hymns among the exarchs too; there is certain information that the

Georgian exarch Moses, gathered the best connoisseurs and performers of the Georgian

hymns from, different eparchies in 1839 and he himself harmonised the melodies of the

church chants. Sometime later Exarch Evsevi (1856-1877) also paid great attention to this

sphere. He ordered to introduce teaching Georgian church hymns in the Theological

Seminary, However and unfortunately, teaching was stopped when he lost this position before

the 1990s. [34]

The imperial power of Russia paid special attention to the clergy whom they probably

thought to be faithful allies and a supporting ideological force for spreading Russia‘s

domination in Transcaucasia. As the mission of ideological preparation and persuasion of

parishioners was fully laid on the lowest layer of the clergy, the government was interested in

improving the social conditions of this layer. In this connection, in 1807 by a decree of the

emperor, representatives of the clergy were freed from serfdom and various taxes, and also

from corporal punishment. A little later, the institute of manager or mouravi was abolished in

villages, [35] and the families of ecclesiastics were freed from the tax, envisaging the support

of the military. [36]

THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION

A number of reforms was carried out in the theological educational system of the Russian

empire at the beginning of the 19th century. A project of reforming theological schools was

affirmed in 1808. ―A commission of theological educational institutions‖ was put at the head

of the system of theological schools, it was subordinated in its turn, to the Holy State Synod.

Apart from that, a four-staged educational system an academy, seminary, a district school and

a parish school was introduced. A clearly defined connection was established between these

four stages: the school of each separate stage was directly subordinated to the educational

institution of the next stage. The academies managed the educational district to which a

certain number of eparchies with all the theological schools belonging to them, were ascribed.

According to the new regulation, the academies were not only theological educational

institutions, but they were also centres of theological science. In this connection the ranks of

master, candidate, and a little later from 1824 of Doctor of Theology were introduced. [37]

After the annexation, the number of Georgian schools and other educational institutions

on the territory of Eastern Georgia considerably diminished. Many of them, among them the

Tbilisi theological seminary, were closed. Besides, the establishing of new ones, but already

reorganized in the Russian manner, was delayed at the beginning. The school for the children

of the nobility reorganized into a gymnasium in 1830, but founded in 1804, was the only

official secular school for a long time, having a state subsidy.

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 73

Solicitation before the Russian Supreme Ecclesiastical Power for establishing a

Theological Seminary in Tbilisi began as early as in 1809, however, it was not satisfied under

the pretext of having no means. In 1817 Exarch Feofilakt‘s petition for opening the

Theological Seminary and Theological Schools in Georgia was also rejected; though the Holy

Governing Synod allowed His Holiness the Exarch of Georgia to borrow the sum necessary

for establishing such educational institutions from the means, given by the same Synod to the

―Ossetian Ecclesiastical Commission‖ in 1816. Due to such material provision, the Russian

Theological Seminary with a District School and a Parish school were opened in Tbilisi in

1817 with great festivities. On October 10 of the same year a district theological school and a

parish school were established in Telavi and in 1817-1818 in Sighnagi and Gori. It is

noteworthy that all the theological and educational institutions in Georgia were financed from

the local budget, by means obtained from the church income of the Georgian exarchate; it is

quite natural, for the main function of all these ―breeding grounds of theological education‖

was the preparing of spiritual teachers with imperial impulses in their souls for Georgian

parishioners who, while doing their duty, i.e., during the divine service would instill in the

souls of their parishioners loyalty to the autocratic regime and serve the Russianizing of the

Georgian population.[38]

At the beginning the teaching course of the Tbilisi Theological Seminary was not

complete and the lessons were devoted only to rhetoric. The course of philosophy was

introduced only in 1823, and that of theology in 1827. Persons from various ends of the

Russian empire were appointed teachers, and due to the scantiness of the budget, salaries they

were paid were scanty. Besides, as a rule, mainly failures, unskilled specialists arrived in

Georgia. Owing to the deficit of the pedagogical personnel in the Tbilisi Theological

Seminary frequently it was impossible to teach the obligatory course of subjects envisaged by

the ―seminary regulations.‖ Consequently, the given circumstances considerably prevented

transferring the students of the Tbilisi Theological Seminary to the Theological Academy.[39]

In the theological schools of Georgia without taking the local conditions into

consideration, the rules established in Russian educational institutions were mechanically

transferred to Georgia. The educational process was accompanied by Russian flogging; very

often the names of students were changed in the Russian manner on the initiative of the

administration of the theological educational institutions: in the majority of cases the

foundation of ―renewed‖ surnames was the patronymic of the student, the ecclesiastical rank

or the Russian translation of the same Georgian surname. As a rule, in the majority of cases

these derived surnames adhered to the people and passed from generation to generation.[40]

From time to time the character, direction and programme of the educational system in

the Caucasus were changed according to state interests and Russia‘s imperial policy. The

question of education appeared in close connection with the far-reaching plans of the Russian

colonial policy. It should be noted that the imperial government at the given stage in every

way supported the study of the local speech with the purpose of instilling and spreading the

Christian faith and activising the missionary activities among the Caucasian peoples. The

evidence of this is ―the letter‖ of February 8, 1834 Baron Rozen to the minister of education

Uvarov which says, ―The obstacles occurring because of a lack of Russian officials knowing

local languages are felt while governing the Transcaucasian Region. To avoid this, it is

necessary to impose upon the local authorities of education to take all kinds of steps to make

the children of Russian officials, brought up in these schools to thoroughly learn the local

languages, taught there, especially the Tatar language, as the most necessary one in the

Complimentary Contributor Copy

74 Khatuna Kokrashvili

greater part of the Transcaucasian region. To achieve this aim of the government some

encouraging measures do not seem to be superfluous, for instance, awarding the pupils,

distinguished by their success in these languages at school-leaving time, with gold and silver

medals and by appointing a certain sum of money to the poorest of them for the initial

acquisition…‖ [41]

In the first half of the 19th century in the conditions of the scanty educational network

found in Georgia, the complete Russification did not seem to be an effective measure. Before

the final completion of conquering the Caucasian region by the Russian empire the local

languages had to fulfil quite a clear cut mission, i.e., at the given stage on the territories which

were to be turned into colonies, with the aborigine population worshipping heathen gods or in

a better case-professing Islam, with the help of local languages Christianity should be

instilled. The imperial power considered it to be of great importance, for they thought it to be

the main component of the state ideology and the expression of the Russian mentality.

When spreading Christianity in the Caucasus the imperial power always considered

Georgia to be an important support; consequently, the preparation of future ecclesiastical,

official and missionary personnel both in secular and theological educational institutions of

Georgia requested the inclusion of the Ossetian and Tatar languages into the list of obligatory

subjects, alongside Georgian and Russian.

Missionary Activities

In the epoch under study the Russian empire‘s policy, as well as its aspiration to expand

its frontiers, demanded activising the missionary activities with special force.

Long before these events, as early as in the 18th century on the initiative of the Georgian

ecclesiastics, working in Moscow, ―An Ossetian Ecclesiastical Commission‖ was founded

whose aim mainly was to spread the Christian faith among the Ossets. In 1815 by the decision

of Emperor Alexander I this commission resumed functioning after it had stopped in 1792.

Besides, the sphere of its activities considerably expanded, embracing the process of

Christianizing not only of the Ossets, but also other mountain peoples. The main work of the

―Ossetian Ecclesiastical Commision‖ had the following direction: building churches and

monasteries and performing various missions for instilling the Orthodox, Christian faith

among the mountain peoples, opening theological educational institutions and the work of

translators for providing the local inhabitants with theological literature etc. in their native

language, Initially the state apportioned a fiscal sum of 14,750 rubles; apart from that, a

detachment of 100 Kazaks were sent to be at the disposal of the Mission, the so called ―Kazak

hundred men detachment‖ and 30 peasant-guides. The Commission resumed its work in

Tbilisi under the Right Reverend Dosytheos Pitskhelauri Archbishop of Telavi Georgia and

the Caucasus. Of course, the Commission was directly subjected to the Governing Holy

Synod. At different times the following Georgian public figures distinguished themselves in

educational-missionary work: Nikoloz Samarganov, Ioane Ialguzidze, Ioseb Eliozidze, Petre

Avaliani, Bessarion Iluridze, Vasili Tseradze, Giorgi Amiridze, Zakaria Mamulashvili and

Iakob Zamtarauli.

The result of the hard work of the ―Ossetian Ecclesiastical Commission‖ during 1817-

1820 was that about 18,592 mountain people were converted to Christianity. The activities of

the Commission were especially fruitful and effective in the period when Feofilakt Rusanov

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 75

was the exarch. At this time instructions were prepared, establishing the rules of the

behaviour of missionaries. viz: to convert the mountain people, missionaries were to use

―more spiritual than secular motives,‖ not to leave the community but to continue preaching

until the newly converted express a wish of having their own church and priest; not to begin

discussing mundane affairs; to go to do the sacred work without telling anybody of it and

without an escort, and present oneself not as one sent by the government, but as a simple

wanderer, wanting everybody to be saved. And finally, to leave the place where their teaching

was not accepted peacefully, and where it was accepted to stay there to teach the people and

to make their belief firmer.‖ [42]

The activities of ―the Biblical Society,‖ founded in Petersburg in 1812, in Russia‘s

policonfessional social environment was fully devoted the missionary and religious-

propagandist work. The Bible and various models of divine literature were translated into

different languages in a great hurry. Translating such literature into the languages of the

Caucasian peoples became more pressing after the ―Ossetian Ecclesiastical Commission‖

resumed its work. For example, it was Ioane Ialguzidze who particularly distinguished

himself in translating such literature from the Georgian language into Ossetian. He translated

the Gospel, the catechism, various prayers, divine liturgy, etc. [43]

From the 1820s the missionary activities of the ―Ossetian Ecclesiastical Commission‖

penetrate into Abkhazia. However at the start, due to the strong opposition of the Muslim

inhabitants, the mission did not succeed. For instance, the result of the missionary preaching

of the archimandrite Ioaniki was that only 216 Abkhazs were converted to Christianity. But

later, namely from the second half of the 19th century, the activities of the Christian

missionaries in Abkhazia turned out to be more fruitful. The ―Ossetian Ecclesiastical

Commission‖ also took care of converting the Inguilos and Muslim inhabitants who were

ethnic Georgians of the recently joined historic province of Samtskhe-Saatabago. However,

the activities of the mission were not so successful. [44]

It should be noted here too that in the first half of the 19th century the Holy Synod had not

as yet worked out a united plan for missionary work. The heavy burden of the mission‘s work

lay on the shoulders of local hierarchs. [45] The missionaries had to work under the hardest

conditions and very often problems with paying salaries occurred. Besides, being a

missionary was not considered to be a prestigious occupation in Russia‘s ecclesiastical circles

and therefore it was not very popular. Consequently, the activities of the ―Ossetian

Ecclesiastical Commission‖ in this respect turned out to be rather unsuccessful among the

mountain inhabitants of the Caucasus with the exception of the Ossets. The very character of

the measures, carried out by the government under the aegis of inculcating and spreading the

Christian-Orthodox faith and also the clumsy interference on the part of the state in the

processes of forming a religious orientation which concealed the wish of encroaching upon

new territories.

This caused a just indignation and fierce resistance of the mountain population of the

Caucasus; with time this opposition turned into a holy war.

The plunder of church property

The plunder of the cultural heritage of the Georgian church, the despising of the local

customs, arbitrary disposal of national values and property belonging to churches and

Complimentary Contributor Copy

76 Khatuna Kokrashvili

monasteries – all this became an integral part of the hierarchs‘ policy in Georgia. Very often

the plunder of the national treasury became an official source of their income. Unfortunately,

alongside the Russian ecclesiastics some renegades from the Georgian clergy also actively

participated in appropriating the valuables of churches and monasteries left without

superintendence. In 1818 under the instruction of the exarch Feofilakt Rusanov a list of all

acting and closed churches and monasteries in Eastern Georgia was compiled, with an

appended description of the valuables and church silver, kept in them. However, after they

had been brought to Tbilisi all these valuables disappeared without leaving any trace. In 1820

by a voluntary decision of the same Feofilakt Rusanov the inn or caravan-serai of Tbilisi

Sioni Cathedral was sold. It was also he who distributed church lands. In 1844, during the

rule of another exarch, Iona, valuables brought from David-Gareja

monastery to Tbilisi were lost. By the exarch‘s instructions and on the basis of the request of

the Holy Synod the ancient banners and the old armour were given to the military governor.

The further fate of these military relics is unknown to this day. [46]

Thus in the first half of the 19th century the Russian supreme power both secular and

ecclesiastical finally abolished the independence of the Georgian Orthodox Christian Church,

turning it into an insignificant, if not a miserable, appendage to the Russian Church. All this

was done by ignoring and violating the World Church Law by the Russian empire. It is a

universally known fact that the abolition of the autocephaly of any independent church is

possible only if there is a decision of the Ecumenical Council concerning it and if there is the

consent of the same independent church, and not against its will and desire. As for Georgia,

the position of the Catholicos-Patriarch was abolished with a brazen violation of World

Church Law and, without elementary justice, the structural-administrative form of the

Georgian Orthodox Christian Church was changed, its property independence was violated

and its relations and close connection with parishioners and the whole of the Georgian people

were broken, and finally the relations between the church and state underwent a radical

change.

With the establishment of the exarchate, the Georgian church was forcibly subjected to

the administrative organ of an alien state, i.e., to Russia‘s Holy Synod. The local church

management was under the control of the government of the Synodal office, and the church

itself with the Georgian clergy found themselves in direct dependence on the state exchequer.

In a word, the church gradually became the means of realizing the Russianizing policy in

Georgia, and this in its turn caused the alienation of the Georgian population from the clergy,

and very often the appearance of opposition between them and a gradual dying of religious

feelings.

Christian sects in Georgia

In the first half of the 19th century, the Russian authorities took active steps against the

various groups of sects which multiplied in Russian Orthodox churches, as the latter from the

government‘s point of view presented a religious form of social protest. As the revolutionary

processes revived in Western Europe the attitude of the emperor Nicholas I towards the sects

became noticeably worse. According to the degree of their danger all the sects on the territory

of the Russian empire were divided into three groups: the most dangerous for the government

were the groups of members of a sect refusing the very concept of state, the institute of

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 77

marriage and refusing to pray for the emperor. Among them were the Dukhobors, Khlists and

Molokans. The severest measures were taken against them by the government, they were not

allowed to build new houses where they would pray, or to restore and repair the old ones;

representatives of the local power removed crosses from their church bell towers and forbade

the members of the sects to ring bells during their rites; besides all this, there were cases of

pogroms of the spiritual centres of both their members and of dissident communities. From

the 1820s to the 1830s there were programs of exiled sect members from the southern and

central regions of Russia to the outskirts of the empire.

The Christian sects did not appear in Georgia in the local conditions: their appearance

both in Georgia and in the whole of the Transcaucasian region can be considered to be the

result of Russia‘s colonial policy. One of the first groups of such people that settled down in

Georgia, namely in Redut-Kale and Sukhumi were the Skoptsi (Eunuchs). [49] From the

1830s began the process of a purposeful deportation of various groups such as the Dukhobors,

Skoptsis, Molokans and Staroobryadtsi, from different regions of the Russian empire to

Georgia. This process was assisted in many ways by the decree of May 27, 1835, according to

which the especially dangerous and harmful sects were allowed to become members of the

civilian town society of the Transcaucasian region. [48]

In the 1830s it was decided to enlist all the active Dukhobors in the military in the

Caucasian corps, and to deport those unfit for military service to the Transcaucasian

provinces. In 1831 the first current of Dukhobors appeared in Transcaucasia, namely in the

gubernias Tbilisi and Elisavetpol, and also in the Kars district. On arrival in the Tbilisi

gubernia, they were distributed in two districts: Akhalkalaki and Borchalo. The process of

deportation lasted till 1845 inclusive.[49] It is noteworthy that the imperial authorities took

special care of the deported Dukhobors. According to the instruction of May 2, 1843 the

Dukhobors received arable lands and pastures on extremely advantageous terms. [50]

From 1830 the process of moving Molokans to Transcaucasia began. Currents of

migrants arrived in the Tbilisi gubernia in 1839-1847. The Molokans settled down in both

inner and borderline regions of Georgia. The religious centre, common to all, was situated in

the village of Voronovka in Borchalo district. On the initiative of the vice-roy of the tsar in

the Caucasus, Count Mikhail Vorontsov, a special commission was organized which, in its

turn, worked out various suggestions to improve the living conditions of migrants. The

Molokans received land, 30-60 desyatins per each family; apart from that the state gave them

certain sums as a credit for expenses when moving and seeds, and, finally, they were freed

from all taxes for a certain period of time. Besides, the government established a strict

supervision that the people should not organize praying houses, and should not give shelter to

people without passports in their houses, should not hire Orthodox Christians as workers or

vice versa; the worshippers had the right to move within the Transcaucasian provinces, but

not in towns. [51]

In 1842, the functioning of one of the currents of the Molokan sect the so called jumpers,

is certified. The latter had their prayer house in Tbilisi, in Peskov Street. [52]

In this way the tsarist government skillfully used the Christian sects in its interests,

namely, it created favourable conditions for them to settle down firmly in new places of

habitation. This was done in the process of the colonization of the Transcaucasian region.

According to the consideration, deep rooted in the Georgian historiography, acting in this

way, tsarism solved several problems at the same time: it rid itself of sects in the central

regions of Russia, deporting them to the provinces on the outskirts of the empire; on the other

Complimentary Contributor Copy

78 Khatuna Kokrashvili

hand, the Russian church by this weakened the keenness of inner contradictions, for the

groups were thought to be by the government the oppositional and hostile to the state forces.

At the same time, by the deportation of the sects the imperial power created a sects‘ migration

to Transcaucasia resulting in a noticeably changed demographic balance of the local

population in favour of the Russian element. Apart from all else, the sect members, settled in

the Georgian borderline zone and were considered by the government to be a powerful anti-

Turkish force.

The Catholic Church in Georgia

Owing to Russia‘s religious policy, the life of Georgian Catholics also changed radically.

As early as 1735 the adoption of the catholic faith by Orthodox Christians was forbidden in

the whole of Russia. After the annexation, as should be expected, this interdiction spread to

Georgia too. It should be noted that in the Russian empire the attitude of the authorities

towards catholic missionaries and their activities was suspicious. They considered the latter to

be agents of European countries. Consequently, the imperial government constantly

oppressed the eastern Catholic missions. On the same basis, the commander-in-chief,

Knorring, forbade the arrival of the European catholic missionaries in Georgia, he threatened

them with banishment. The divine service and the regulation of the church in Latin were also

forbidden in Georgian Catholic churches. In 1844 an official decision of interdicting the

activities of Catholic missionaries was taken; if the latter did not obey the Mogilyovsk

consistory. However, the representatives of the Catholic mission, present in Georgia at that

time, refused point blank to agree to such conditions and preferred to leave the country. [53]

Having lost their spiritual teachers the Catholic flock was obliged to obey the Mogilyovsk

consistory which, in fact, followed the Armenian-Gregorian regulations. As is known, during

the whole of their history the Georgian Catholics conducted divine service by the Latin

regulations of the church. Consequently, with the purpose of preserving their self-

identification they left Georgia and founded their churches in Constantinople and Montoban,

France. But the part that stayed in their home country was obliged to agree to using the

Armenian regulation. From this time, on the Armenian Catholic priests when christening

changed the surnames of ethnic Georgians and wrote them down in the Armenian manner. In

this way began the process of Armenizing Georgian Catholics.

Thus, at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries the use of religious factors in political interests

noticeably strengthened in the Russian empire. As a matter of fact Orthodox Christianity

served as a means of assimilating neighbouring territories and leading its own colonial policy.

In the first half of the 19th century after the annexation of the Georgian state the church

reform carried out in Georgia by the imperial power, served a definite aim that of the

inculcation of the rules of the Russian divine service and the establishment of the church

organization controlled by the state as much as possible. It also implied the radical structural-

administrative reorganization of the Georgian church, the commutation of the church taxes

i.e., the change from paying taxes in kind to paying money and the secularization of church

lands; apart from that the reorganization of the order of the divine service and the change of

the position of the lowest layer of the clergy was planned. The result of the church and

religious policy, carried out by the imperial power, was that the autocephaly of the Georgian

church was abolished and the position of exarch was established. Owing to this, the

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 79

structural-administrative form of the church was changed and it became completely subjected

to the Holy Synod. Consequently, by this the inviolability of the church property was broken

and, alongside it the Georgian clergy found itself dependent on the state exchequer. Apart

from that, owing to the reform carried out, the close connection of the church with its parish

was broken, its attitude towards the Georgian state also changed. With time the church

became the means of carrying out the Russianizing policy in Georgia.

The appearance of religious sects in Georgia is a direct result of Russia‘s colonial policy.

On the other hand, the measures, taken towards the Catholic church conditioned the

development of the process of Armenian Georgian Catholics.

The compulsory and forcible church policy of the Russian power, the establishment of

the state control on the church, the attempt to suppress national traditions and the persecution

of the national culture, the weakening and very often the destruction of the connection

between the church and its flock, all these circumstances became the reason for the

development and aggravation of the contrary processes among the local inhabitants of both

Christian and non-Christian faith. As could be expected such a policy gave birth to religious

indifference, and in other confessional groups to an acute anti-Orthodox reaction.

REFERENCES

[1] Tsagareli, A. Deeds and Other Historical Documents of the 18th century, Concerning

Georgia, vol. I SPB, 1898, 413.

[2] Bishop Kirion. A Twelve Century Long Religious Fight of Georgia with Islam. Tiflis,

1899, 81-83.

[3] Vachnadze, M; Guruli, V. The History of Russia – the 20th Century, Tbilisi, 2003. G.

Rtskhiladze. Georgia‘s Foreign Policy of the 2nd Half of the 18th Century and a

Religious Factor. In the magaz. ―Religia,‖ 1999 No-s 3,4. T. Panjikidze, The Religious

Factor in the Formation of the Conception of the Foreign Policy of Georgia in the book:

Religious Processes in Georgia at the Turn of the 20th-21st Centuries, Tbilisi 2003,

69-71.

[4] E. K. A Brief Essay of the History of the Georgian Church and the Exarchate in the 19th

Century, Tiflis, 1901, 6-8.

[5] Javakhishvili, I. Russian-Georgian Interrelations in the 18th Century, Tbilisi, 1919,

49-57.

[6] Monuments of Georgian Law, Tbilisi, Vol. 2, p. 469.

[7] Bubulashvili. E. The Georgian Orthodox Christian Church in the Period of the

Exarchate, a Synopsis of Thesis to Obtain the Degree of Doctor of History, Tbilisi,

2006, p. 12.

[8] Javakhishvili, I. Russian-Georgian Interrelations in the 18th Century, Tbilisi, 1919, 57-

64; cf. A. Bendianishvili, A National Question in Georgia in 1801-1921, Tb., 1980, 8.

[9] Dubronravin, R. An Essay of the History of the Russian Church, SPB., 1863, 192:

History of Religion in Russia, under the general edition of Trofimchuk, M., 2002,

141-142.

[10] The History of Religion in Russia, under the general edition of Trofimchuk, M., 2002,

141-142.

Complimentary Contributor Copy

80 Khatuna Kokrashvili

[11] Ibidem. 131-133.

[12] Rogava, G. Religion and Church in Georgia in the 19th-20th Centuries, Tbilisi, 2002, 33.

[13] Acts, Collected by The Caucasian Archeographic Commission, edited by A. Berzhe,

vol. I, part II, Tiflis, 1866, 413.

[14] Acts, Collected by The Caucasian Archeographic Commission, edited by A. Berzhe,

vol. II, Tiflis, 1866, 269.

[15] E. K. A Brief Essay of the History of the Georgian Church and the Exarchate in the 19th

Century, Tiflis, 1901, p. 11. N Dubrovin, Giorgi XII, the Last King of Georgia and

Joining it to Russia, SPB, 1897, 200-201.

[16] Tsagareli, A. Deeds and Other Historical Documents of the 18th Century, Concerning

Georgia, vol. II, publ. I, SPB. 1898, 201; also: G. Rogava, The Abolition of the

Autocephaly of the Georgian Church, magazine ―Religia,” 1998, Nos 5-6, 14.

[17] Bubulashvili, E. The Catholicos-Patriarch of Georgia – Anton II, Tbilisi, 2002, 27-32.

[18] E.K. A Brief Essay of the History of the Georgian Church and Exarchate in the 19th

century, Tiflis, 1901, 35.

[19] The History of the Christian Church in the 19th Century, publ. of A. P. Lopukhin, vol.

II, part II, Petrograd, 1901, 571-572.

[20] Rogava, G. Religion and Church in Georgia, Tbilisi, 2002, 20-21.

[21] The Report of the Synod, 1811, p. 2.

[22] Bubulashvili, E. The Georgian Orthodox Christian Church in the Period of the

Exarchate, Synopsis of Thesis to obtain the Degree of Doctor of History, Tbilisi, 2006,

17-18.

[23] E.K. A Brief Essay of the History of the Georgian Church and Exarchate in the 19th

century, Tiflis, 1901, p. 54.

[24] Rogava, G. The Abolition of the Autocephaly of the Georgian Church, magazine

―Religia,‖ 1998, No-s 5-6, p. 20.

[25] The History of the Christian Church in the 19th Century, publ. of A. P. Lopukhin, vol. 2,

part II, Petrograd, 1901, p. 573.

[26] Bubulashvili, E. The Georgian Orthodox Christian Church in the Period of Exarchate,

Synopsis of Thesis to Obtain the Degree of the Doctor of History, Tbilisi, 2006, p. 19.

[27] Shakiashvili, T. The Georgian Church in the First Half of the 19th Century, Monastery

Economy, in the collection of works ―Questions of Georgia‘s New History, VIII,

Tbilisi, 2005, 132-148.

[28] Rogava, G. Religion and Church in Georgia, Tb., 2002, 29-30; also M. Tadumadze,

Church Landownership in Georgia (the 1st half of the 19th Century), Tbilisi, 2006, p. 86.

[29] Rogava, G. Religion and Church in Georgia, Tbilisi, 2002, 31-32.

[30] Nikolski, NM. The History of the Russian Church 3rd edition, M. 1983, 220-221.

[31] The History of the Christian Church in the 19th Century, A. P. Lopukhin‘s edition, vol.

2, part II, Petrograd, 1901, p. 567.

[32] Acts, Collected by the Caucasian Archeographic Commission, edited By A. Berzhe,

vol. II, Tiflis, 1868, p. 268.

[33] Ibidem, p. 268.

[34] E.K. A Brief Essay of the History of the Georgian Church and Exarchate in the 19th

Century, Tiflis, 1901, p. 185.

[35] Georgia‘s Central State Archive of History, F. 488, d. N84, l 7-8.

[36] Georgia‘s Central State Archive of History, F. 488, d N84, l 5.

Complimentary Contributor Copy

The Russian Empire‘s Religious Policy in Georgia 81

[37] Essay on the History of the Russian Church, SPB, 1863, p. 174. The History of

Religion in Russia under the general editorship of Trofimchuk, M. 2002, p. 148.

[38] Aleksidze, M. The Russificatory Policy of Tsarism in the Tbilisi Theological Seminary

and Fight for the Georgian language, a thesis to obtain the degree of candidate of

history (synopsis of thesis). Tbilisi, 1998, p. 20.

[39] Khundadze, Tr. Essays on the History of People‘s Education in the 19th century

Georgia, Tbilisi, 1957, p. 183.

[40] Ibidem, p. 187.

[41] Acts, Collected by the Caucasian Archeographic Commission, ed. By. A. Berzhe, vol,

VIII, Tiflis, 1881, p. 99.

[42] E.K. A Brief Essay of the History of the Georgian Church and Exarchate in the 19th

Century, Tiflis, 1901, p.97.

[43] Georgia‘s Central State Archive of History, F. 488, d N621.

[44] Ibidem, p.p. 102-103; also V. Tsverava. The Missionary Activities of the Georgian

Exarchate in 19th century Kutaisi, 2003, 100-101.

[45] The History of Religion in Russia, under the general editorship of Trofimchuk, M.

2002, p. 152.

[46] Bubulashvili. E. From the History of the Russian Exarchs‘ Activities (the 1st Half of the

19th Century) in the collection of works: The Questions of the New and Newest History

of Georgia, I, 2007, 246-247, 250.

[47] Songulashvili, A. ―From the History of the Religious Sects in Georgia, in the collection

of works: The Questions of the New and the Newest History of Georgia, I, 2007, p.

330, also: L. Chanchaleishvili Believers in the Old Faith (Staroveri), Living in Georgia

(a historic-ethnographic survey), magazine ―Clio,‖ No13, Tbilisi, 2001.

[48] Rogava, G. Religion and Church in Georgia, Tbilisi, 2002, p. 279.

[49] Ibidem, 257-259.

[50] Ibidem, p. 260

[51] Ibidem, p. 280

[52] Ibidem, p. 287.

[53] Papashvili, M. Georgia‘s Relations with Rome, Tb., 1995, 310-314.

Complimentary Contributor Copy

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chapter 7 RizalDocument3 pagesChapter 7 RizalJohnpert ToledoNo ratings yet

- How World Religion BeganDocument5 pagesHow World Religion BeganJay Neri Anonuevo100% (1)

- Yeshua Jesus in All The Books of The Bible PDFDocument2 pagesYeshua Jesus in All The Books of The Bible PDFBettyNo ratings yet