Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 186.1.139.130 On Tue, 05 Jan 2021 02:53:04 UTC

Uploaded by

FeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 186.1.139.130 On Tue, 05 Jan 2021 02:53:04 UTC

Uploaded by

FeCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter Title: Acknowledgments

Book Title: Beyond the Bauhaus

Book Subtitle: Cultural Modernity in Breslau, 1918-33

Book Author(s): Deborah Ascher Barnstone

Published by: University of Michigan Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1gk088m.3

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

University of Michigan Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Beyond the Bauhaus

This content downloaded from

186.1.139.130 on Tue, 05 Jan 2021 02:53:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Acknowledgments

I first heard of the city of Breslau as a child from my father, Abraham Ascher,

who was born there. I must confess, however, that for decades the city re-

mained only a remote name since my father’s family had all fled or been mur-

dered by the Nazis, and Breslau after the war became Wroclaw, a Polish city

situated behind the Iron Curtain that was virtually inaccessible to those of us in

the West. Indeed, I knew shamefully little of my father’s Heimatstadt until my

father decided to author his own study on the city, specifically on the Jewish

community that had resided there during the Nazi period between 1933 and

1941. It was, in fact, toward the final stages of producing his book that my fa-

ther called one day to inform me that he had discovered material of art histori-

cal interest that might prove interesting to me. He sent me a small collection of

official Nazi correspondence from 1935–37 about the extraordinary art Nazi

officials had discovered in private Jewish collections in Breslau. My father was

correct; the letters were a revelation, although not precisely for the reasons that

he had anticipated. For, as I researched Breslau, I soon discovered that it had

been home to an extraordinary community of forward-thinking people during

the 1920s who were arts patrons but also artists, architects, and urban design-

ers, many of whom are still world renowned today. Equally exciting was the

discovery that almost none of this history had been documented or dissemi-

nated in any language, much less in the English-speaking world. Thus, I have

to thank my father first and foremost for this project.

As with any book-length study there are innumerable people who offered

support, advice, and expertise along the way. Franziska Bollerey enthusiasti-

cally encouraged me to pursue the project when I was formulating the idea for

the book. The German Academic Exchange Service, Washington State Univer-

sity Saupe Fund for Excellence, the Technical University Delft, and University

of Technology Sydney Centre for Contemporary Design Practice helped defray

This content downloaded from

186.1.139.130 on Tue, 05 Jan 2021 02:53:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

x Acknowledgments

the costs of traveling to Germany and Poland in order to conduct the necessary

archival research. The archivists at the Wroclaw state archive, University of

Wroclaw Library, the Ethnographic Museum, and the Architecture Museum in

Wroclaw gave me invaluable help locating materials and permitted me to pho-

tocopy enormous quantities of material relevant to my work. I owe a special

thanks to Jerzy Ilkosz, Piotr Łukaszewicz, and Juliet Golden. Juliet was in-

domitable chasing down images and permissions for me. Beate Störtkuhl at the

Bundesinstitut für Kultur und Geschichte der Deutschen im östlichen Europa

pointed me in the right direction at the beginning of the research and gener-

ously shared some excellent resource material from her institute with me. The

archivists at the German National Museum in Nuremburg; Staatsbibliothek in

Berlin; the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz; the Werkbund Archive; the Bau-

haus Archive; and the Academy of the Arts, in particular Heidemarie Bock;

Petra Albrecht; Tanja Morgenstern; and Dr. Eva-Marie Barkofen went beyond

the call of duty in order to offer assistance.

In addition to sitting in archives and libraries, I was fortunate to be able to

interview several people who offered vital perspectives on Breslau; the inter-

view with Brigitte Würtz, Oskar Moll’s daughter, helped me understand the

cultural milieu in Breslau during the 1920s as well as the outstanding art made

by both her parents; the interview with Chaim Haller about his wife Ruth’s fa-

ther, Ismar Littmann, provided me with important insights into collecting in

Breslau; Walter Laqueur shared some key memories; and the lawyer Willi Korte

helped me understand the complex nature of looted art research and recovery.

Portions of three chapters were previously published as articles. Part of

chapter 4, “The Breslau Academy of Fine and Applied Arts,” was published in

the Journal of Architectural Education; part of chapter 6, “Between Idealism

and Realism: Architecture in Breslau,” was published in the New German Cri-

tique; and part of chapter 5, “Dissemination of Taste: Breslau Collectors, Art

Associations, and Museums,” was published in The Art Journal. In addition,

much of the material in this book was initially tested in academic conference

presentations, from which I received detailed and valuable feedback. These

included the German Studies Association and the Association of Art Historians

of Great Britain.

The two readers for University of Michigan Press, professors Elizabeth

Otto and Claire Zimmerman, both gave the manuscript a thorough reading,

delivering extremely insightful and helpful criticism and direction at a crucial

time in the project. Without their tough but thoughtful comments, the book

would have been far weaker indeed. Lastly, I would like to thank my husband,

This content downloaded from

186.1.139.130 on Tue, 05 Jan 2021 02:53:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Acknowledgments xi

Robert, and my children, Alexander and Maya, who all tolerated my obsession

with Breslau, my frequent absences, and hours upon hours spent glued to my

computer. My children are convinced that I cannot survive without my laptop!

Without their love and support, I would not have completed this book. As with

every such endeavor, the strengths exist because of the many people who sup-

ported me. As to the faults—I have no one to blame but myself.

This content downloaded from

186.1.139.130 on Tue, 05 Jan 2021 02:53:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

This content downloaded from

186.1.139.130 on Tue, 05 Jan 2021 02:53:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Daniel Gilfillan-Pieces of Sound - German Experimental Radio (2009)Document240 pagesDaniel Gilfillan-Pieces of Sound - German Experimental Radio (2009)La Oveja Negra Espacio Radiofónico100% (1)

- Fearful Spirits, Reasoned Follies: The Boundaries of Superstition in Late Medieval EuropeFrom EverandFearful Spirits, Reasoned Follies: The Boundaries of Superstition in Late Medieval EuropeNo ratings yet

- Ideology and the Rationality of Domination: Nazi Germanization Policies in PolandFrom EverandIdeology and the Rationality of Domination: Nazi Germanization Policies in PolandNo ratings yet

- Winter - The Day The Great War Ended, 24 July 1923. The Civilianization of War (2022)Document260 pagesWinter - The Day The Great War Ended, 24 July 1923. The Civilianization of War (2022)William Thomas100% (2)

- The Faustian BargainDocument416 pagesThe Faustian BargainDiego Beck100% (1)

- Nazi SoundscapesDocument274 pagesNazi SoundscapesAnonymous RTeOXp2p100% (1)

- Gregory Borovka - Scythian ArtDocument194 pagesGregory Borovka - Scythian ArtKarela GeigerNo ratings yet

- Vintage Airplane - May 1982Document24 pagesVintage Airplane - May 1982Aviation/Space History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Household: Ucsp11/12Hsoiii-20Document2 pagesHousehold: Ucsp11/12Hsoiii-20Igorota SheanneNo ratings yet

- Artificial Darkness: An Obscure History of Modern Art and MediaFrom EverandArtificial Darkness: An Obscure History of Modern Art and MediaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- BIRDSALL, Carolyn. Nazi Soundscapes PDFDocument274 pagesBIRDSALL, Carolyn. Nazi Soundscapes PDFTiago Pereira100% (1)

- Stories of House and Home: Soviet Apartment Life during the Khrushchev YearsFrom EverandStories of House and Home: Soviet Apartment Life during the Khrushchev YearsNo ratings yet

- Lamm, J. Schleiermacher's PlatoDocument278 pagesLamm, J. Schleiermacher's PlatonicodeloNo ratings yet

- The Absent Jews: Kurt Forstreuter and the Historiography of Medieval PrussiaFrom EverandThe Absent Jews: Kurt Forstreuter and the Historiography of Medieval PrussiaNo ratings yet

- Deaf in the USSR: Marginality, Community, and Soviet Identity, 1917-1991From EverandDeaf in the USSR: Marginality, Community, and Soviet Identity, 1917-1991No ratings yet

- Children of the Greek Civil War: Refugees and the Politics of MemoryFrom EverandChildren of the Greek Civil War: Refugees and the Politics of MemoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- ANS145 - Beef Cattle ProductionDocument52 pagesANS145 - Beef Cattle ProductionEgie BulawinNo ratings yet

- Max Weber in Politics and Social Thought-Joshua DermanDocument300 pagesMax Weber in Politics and Social Thought-Joshua Dermancjmaura100% (7)

- Economizer DesignDocument2 pagesEconomizer Designandremalta09100% (4)

- Interpretations of Renaissance HumanismDocument341 pagesInterpretations of Renaissance HumanismKristina Sip100% (7)

- Beyond the Steppe Frontier: A History of the Sino-Russian BorderFrom EverandBeyond the Steppe Frontier: A History of the Sino-Russian BorderNo ratings yet

- Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First MillenniumFrom EverandPhantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First MillenniumRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Mother Tongue K To 12 Curriculum GuideDocument18 pagesMother Tongue K To 12 Curriculum GuideBlogWatch100% (5)

- Gods and Garments: Textiles in Greek Sanctuaries in the 7th to the 1st Centuries BCFrom EverandGods and Garments: Textiles in Greek Sanctuaries in the 7th to the 1st Centuries BCNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Retail Management of The Brand 'Sleepwell'Document62 pagesThesis On Retail Management of The Brand 'Sleepwell'Sajid Lodha100% (1)

- Laudon - Mis16 - PPT - ch11 - KL - CE (Updated Content For 2021) - Managing Knowledge and Artificial IntelligenceDocument45 pagesLaudon - Mis16 - PPT - ch11 - KL - CE (Updated Content For 2021) - Managing Knowledge and Artificial IntelligenceSandaru RathnayakeNo ratings yet

- Popular Opinion in The Middle Ages PDFDocument366 pagesPopular Opinion in The Middle Ages PDFSergio LagutiniNo ratings yet

- Dreamland of Humanists: Warburg, Cassirer, Panofsky, and the Hamburg SchoolFrom EverandDreamland of Humanists: Warburg, Cassirer, Panofsky, and the Hamburg SchoolNo ratings yet

- The Birth of Modern Belief: Faith and Judgment from the Middle Ages to the EnlightenmentFrom EverandThe Birth of Modern Belief: Faith and Judgment from the Middle Ages to the EnlightenmentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Bauhaus Weaving Theory From Feminine Craft To Mode of Design - SmithDocument273 pagesBauhaus Weaving Theory From Feminine Craft To Mode of Design - SmithAnonymous GKqp4Hn100% (3)

- Holocaust Memory Reframed: Museums and the Challenges of RepresentationFrom EverandHolocaust Memory Reframed: Museums and the Challenges of RepresentationNo ratings yet

- Time’s Visible Surface: Alois Riegl and the Discourse on History and Temporality in Fin-de-Siècle ViennaFrom EverandTime’s Visible Surface: Alois Riegl and the Discourse on History and Temporality in Fin-de-Siècle ViennaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Arrested Development: The Soviet Union in Ghana, Guinea, and Mali, 1955–1968From EverandArrested Development: The Soviet Union in Ghana, Guinea, and Mali, 1955–1968No ratings yet

- Objects of Culture: Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial GermanyFrom EverandObjects of Culture: Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial GermanyNo ratings yet

- Brill Printing Spinoza: This Content Downloaded From 95.74.242.115 On Mon, 23 Jan 2023 17:48:22 UTCDocument3 pagesBrill Printing Spinoza: This Content Downloaded From 95.74.242.115 On Mon, 23 Jan 2023 17:48:22 UTCVittorio olivieriNo ratings yet

- The Day The Great War Ended 24 July 1923 The Civilianization of War Jay Winter Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Day The Great War Ended 24 July 1923 The Civilianization of War Jay Winter Full Chaptermarlys.synder151100% (5)

- Art and Scholarship (E.H. Gombrich)Document16 pagesArt and Scholarship (E.H. Gombrich)isabel margarita jordánNo ratings yet

- "We Will Never Yield": Jews, the German Press, and the Fight for Inclusion in the 1840sFrom Everand"We Will Never Yield": Jews, the German Press, and the Fight for Inclusion in the 1840sNo ratings yet

- Children of Communism: Politicizing Youth Revolt in Communist Budapest in the 1960sFrom EverandChildren of Communism: Politicizing Youth Revolt in Communist Budapest in the 1960sNo ratings yet

- Death and a Maiden: Infanticide and the Tragical History of Grethe SchmidtFrom EverandDeath and a Maiden: Infanticide and the Tragical History of Grethe SchmidtRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- J ctt1ww3w0s 4Document5 pagesJ ctt1ww3w0s 4Victor YaoNo ratings yet

- Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750-1970From EverandDown from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750-1970Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Making A Case The Practical Roots of Biblical Law Sara Milstein Full ChapterDocument67 pagesMaking A Case The Practical Roots of Biblical Law Sara Milstein Full Chaptersharon.holley140100% (6)

- To the Collector Belong the Spoils: Modernism and the Art of AppropriationFrom EverandTo the Collector Belong the Spoils: Modernism and the Art of AppropriationNo ratings yet

- Between Yesterday and Tomorrow: German Visions of Europe, 1926-1950From EverandBetween Yesterday and Tomorrow: German Visions of Europe, 1926-1950No ratings yet

- Wires That Bind: Nation, Region, and Technology in the Southwestern United States, 1854-1920From EverandWires That Bind: Nation, Region, and Technology in the Southwestern United States, 1854-1920No ratings yet

- Legacy of Blood Jews Pogroms and Ritual Murder in The Lands of The Soviets Elissa Bemporad Download PDF ChapterDocument51 pagesLegacy of Blood Jews Pogroms and Ritual Murder in The Lands of The Soviets Elissa Bemporad Download PDF Chaptermichael.neumeyer280100% (16)

- The Unchosen Ones: Diaspora, Nation, and Migration in Israel and GermanyFrom EverandThe Unchosen Ones: Diaspora, Nation, and Migration in Israel and GermanyNo ratings yet

- The Early Modern Dutch Press in An Age of Religious Persecution The Making of Humanitarianism David de Boer Full ChapterDocument68 pagesThe Early Modern Dutch Press in An Age of Religious Persecution The Making of Humanitarianism David de Boer Full Chapterjohn.staten431100% (6)

- British liberal internationalism, 1880–1930: Making progress?From EverandBritish liberal internationalism, 1880–1930: Making progress?No ratings yet

- Empire, the British Museum, and the Making of the Biblical Scholar in the Nineteenth Century: Archival CriticismFrom EverandEmpire, the British Museum, and the Making of the Biblical Scholar in the Nineteenth Century: Archival CriticismNo ratings yet

- Noble Bondsmen: Ministerial Marriages in the Archdiocese of Salzburg, 1100–1343From EverandNoble Bondsmen: Ministerial Marriages in the Archdiocese of Salzburg, 1100–1343No ratings yet

- 2011 StIC PeterLangDocument203 pages2011 StIC PeterLangMary MoshNo ratings yet

- Visitors to the House of Memory: Identity and Political Education at the Jewish Museum BerlinFrom EverandVisitors to the House of Memory: Identity and Political Education at the Jewish Museum BerlinNo ratings yet

- Markus Friedrich The Birth of The ArchivDocument288 pagesMarkus Friedrich The Birth of The ArchivpsfariaNo ratings yet

- A Time To Gather Archives and The Control of Jewish Culture Jason Lustig Full ChapterDocument51 pagesA Time To Gather Archives and The Control of Jewish Culture Jason Lustig Full Chapterheath.rasmusson551100% (12)

- Culture From The Slums Jeff Hayton Full ChapterDocument53 pagesCulture From The Slums Jeff Hayton Full Chapterdavid.gallagher608100% (3)

- Anthropology at War: World War I and the Science of Race in GermanyFrom EverandAnthropology at War: World War I and the Science of Race in GermanyNo ratings yet

- Afzal ResumeDocument4 pagesAfzal ResumeASHIQ HUSSAINNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Vinluan Estate in Pangasinan Charged With Tax Evasion For Unsettled Inheritance Tax CaseDocument2 pagesHeirs of Vinluan Estate in Pangasinan Charged With Tax Evasion For Unsettled Inheritance Tax CaseAlvin Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Assessment 4 PDFDocument10 pagesAssessment 4 PDFAboud Hawrechz MacalilayNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Marks and Spencers Retail ChainDocument10 pagesAssessing The Marks and Spencers Retail ChainHND Assignment Help100% (1)

- CUET 2022 General Test 6th October Shift 1Document23 pagesCUET 2022 General Test 6th October Shift 1Dhruv BhardwajNo ratings yet

- LSL Education Center Final Exam 30 Minutes Full Name - Phone NumberDocument2 pagesLSL Education Center Final Exam 30 Minutes Full Name - Phone NumberDilzoda Boytumanova.No ratings yet

- Electromagnetism WorksheetDocument3 pagesElectromagnetism WorksheetGuan Jie KhooNo ratings yet

- Jones Et - Al.1994Document6 pagesJones Et - Al.1994Sukanya MajumderNo ratings yet

- Cheerios Media KitDocument9 pagesCheerios Media Kitapi-300473748No ratings yet

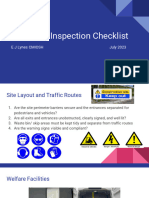

- Work Site Inspection Checklist 1Document13 pagesWork Site Inspection Checklist 1syed hassanNo ratings yet

- A Process Reference Model For Claims Management in Construction Supply Chains The Contractors PerspectiveDocument20 pagesA Process Reference Model For Claims Management in Construction Supply Chains The Contractors Perspectivejadal khanNo ratings yet

- Allegro Delivery Shipping Company Employment Application FormDocument3 pagesAllegro Delivery Shipping Company Employment Application FormshiveshNo ratings yet

- Contigency Plan On Class SuspensionDocument4 pagesContigency Plan On Class SuspensionAnjaneth Balingit-PerezNo ratings yet

- Catalog Tu ZG3.2 Gian 35kV H'MunDocument40 pagesCatalog Tu ZG3.2 Gian 35kV H'MunHà Văn TiếnNo ratings yet

- Reference by John BatchelorDocument1 pageReference by John Batchelorapi-276994844No ratings yet

- Vishal: Advanced Semiconductor Lab King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Thuwal, Saudi Arabia 23955Document6 pagesVishal: Advanced Semiconductor Lab King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Thuwal, Saudi Arabia 23955jose taboadaNo ratings yet

- VLT 6000 HVAC Introduction To HVAC: MG.60.C7.02 - VLT Is A Registered Danfoss TrademarkDocument27 pagesVLT 6000 HVAC Introduction To HVAC: MG.60.C7.02 - VLT Is A Registered Danfoss TrademarkSamir SabicNo ratings yet

- Rab Sikda Optima 2016Document20 pagesRab Sikda Optima 2016Julius Chatry UniwalyNo ratings yet

- Channel & Lomolino 2000 Ranges and ExtinctionDocument3 pagesChannel & Lomolino 2000 Ranges and ExtinctionKellyta RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Ward 7Document14 pagesWard 7Financial NeedsNo ratings yet

- Trading Journal TDA Branded.v3.5 - W - Total - Transaction - Cost - BlankDocument49 pagesTrading Journal TDA Branded.v3.5 - W - Total - Transaction - Cost - BlankChristyann LojaNo ratings yet

- Inspection Report For Apartment Building at 1080 93rd St. in Bay Harbor IslandsDocument13 pagesInspection Report For Apartment Building at 1080 93rd St. in Bay Harbor IslandsAmanda RojasNo ratings yet

- Ice 3101: Modern Control THEORY (3 1 0 4) : State Space AnalysisDocument15 pagesIce 3101: Modern Control THEORY (3 1 0 4) : State Space AnalysisBipin KrishnaNo ratings yet