Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 - CA A Cancer Journal For Clinicians

Uploaded by

Rhaiza PabelloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 - CA A Cancer Journal For Clinicians

Uploaded by

Rhaiza PabelloCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIAL

Sixty Years of CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

Ted Gansler, MD, MBA1; Patricia A. Ganz, MD2; Marcia Grant, RN, DNSc3; Frederick L. Greene, MD4; Peter Johnstone, MD5;

Martin Mahoney, MD, PhD6; Lisa A. Newman, MD, MPH7; William K. Oh, MD8; Charles R. Thomas Jr, MD9;

Michael J. Thun, MD, MS10; Andrew J. Vickers, PhD11; Richard C. Wender, MD12; Otis Webb Brawley, MD13

Abstract

The first issue of CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians was published in November of 1950. On the 60th anniversary of

that date, we briefly review several seminal contributions to oncology and cancer control published in our journal

during its first decade. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:345-350. ©2010 American Cancer Society, Inc.

Happy 60th Birthday CA!

We suspect that most of you have, by now, noticed the American Cancer Society (ACS)’s birthday-themed media

campaign that began a little over a year ago. The point of that message is to memorably and concisely invite others

to join us in working toward “a world with less cancer and more birthdays,” and to summarize our strategy for

accomplishing that goal– helping people “stay well” (prevention and early detection), “get well” (support and infor-

mation for people facing cancer), “fight back” (advocacy), and “find cures” (research).

This article, however, refers to a more literal birthday–the 60th anniversary of the first issue of CA: A Cancer

Journal for Clinicians. Although some scientific and medical journals are far older, CA is among the most venerable

of oncology and cancer control journals.

Nearly all of the content in our journal is focused on current standards of care and on research likely to impact

those standards in the near future. There is still so far to go toward the ACS’s mission of “eliminating cancer as a

major health problem” that time for retrospection is a luxury, especially for a journal with as few pages as CA.

Nonetheless, we feel that after 60 years, it is reasonable to allocate a few pages to a brief look at where we have been.

Members of this editorial board therefore set aside several hours for perusing content from the first decade of CA

(still known at that time as CA: A Bulletin of Cancer Progress). It is impossible for us to summarize a decade of articles

in a few pages, so we will briefly discuss only a few articles that represent each of 4 themes: prevention, early

detection, treatment, and clinician-patient communication. For each theme, we have paired several articles from

CA’s first decade (1950-1959) and the most recent decade (2000-2009, 50 years later).

1

Director of Medical Content, Health Promotions, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA; 2Director, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control Research, Jonsson

Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, CA; 3Director and Professor, Nursing Research and Education, City of Hope Medical Center, Duarte, CA; 4Chairman,

Department of General Surgery, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, NC; 5William A. Mitchell Professor and Chair of Radiation Oncology, Indiana University

School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN; 6Associate Professor of Onocology, Departments of Medicine and Health Behavior, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo,

NY; 7Professor of Surgery and Director, University of Michigan Breast Care Center, Ann Arbor, MI; 8Chief, Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Mount

Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY; 9Professor and Chair, Department of Radiation Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR; 10Vice

President Emeritus, Epidemiology and Surveillance Research, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA; 11Assistant Attending Research Methodologist, Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY; 12Chairman, Department of Family Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA; 13Chief Medical

Officer, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA

Corresponding author: Ted Gansler, MD, MBA, Health Promotions, American Cancer Society, 250 Williams Street, Atlanta, GA 30303; ted.gansler@cancer.org

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Patricia Ganz reports that her husband serves as the Chief Scientific Officer for Intrinsic Life Sciences, and they retain stock in Intrinsic Life Sciences.

Dr. Peter Johnstone serves as President/CEO of the Midwest Proton Radiotherapy Institute. Dr. Martin Mahoney serves as a consultant for Merck; he has received research

funding from Pfizer, and serves as a member of the speaker’s bureau for Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi Aventis. Dr. William Oh has served as a consultant for BIND

Biosciences, Inc.; Genentech; and Centocor Ortho Biotech, Inc. Dr. Andrew Vickers serves as consultant for Theradex and for GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Otis Brawley serves as an

unpaid medical consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, and CNN. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

姝2010 American Cancer Society, Inc. doi 10.3322/caac.20088

Available online at http://cajournal.org and http://cacancerjournal.org

CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:345-350.

VOLUME 60 ⱍ NUMBER 6 ⱍ NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2010 345

Sixty Years of CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

EDITORIAL

The selection of just a few articles to review herein feels the weight of the evidence is increasingly point-

from the quite extensive list of CA articles with genu- ing in one direction: that excessive smoking is one of

ine historical importance was a difficult task, and we the causative factors in lung cancer.”4 In the same is-

salute all of the authors and their articles that were so sue, a tobacco industry representative dismissed the

critical to the fight against cancer but which we were evidence, saying “For at least four years there have

not able to summarize in these pages. been repeated, sensational and fear-arousing state-

ments and resultant headlines on the theoretical lethal

nature of tobacco smoke…the statistical evidence in

Prevention: Lung Cancer Epidemiology support of the cigarette theory has not been accepted

and Tobacco Control as proof of generalized conclusions about smoking by

Tobacco use was, and still remains, the single greatest several distinguished statisticians…”.5 Rutstein then

cause of cancer deaths, and so it is difficult to appreci- rebutted the tobacco industry argument, saying “Lung

ate the level of evidence required for this to become cancer is a serious disease which causes much suffering

accepted. Adverse health effects from smoking had and cuts down people in the prime of life. Should not

been hypothesized much earlier, but it required exten- public health authorities immediately recommend the

sive scientific evidence that began to accumulate dur- obvious remedy suggested by sound epidemiologic

ing the 1950s to remove any reasonable doubt that observation and confirmatory laboratory evidence? If

smoking caused lung cancer in men. not, why not?”6

Fortuitously, the evidence emerged in parallel on The following year, Davies wrote “The American

both sides of the Atlantic. In 1951, the ACS epidemi- Cancer Society considers the facts adequate and con-

ologists Hammond and Horn began planning the first cludes that CIGARETTE SMOKING IS THE

large prospective epidemiological study of smoking in MAJOR CAUSATIVE FACTOR IN LUNG

the United States, coincident with the initiation of the CANCER. This disease offers a greater opportunity

British Doctor’s Study by Doll and Hill in England. for cancer prevention than any other type of cancer.

In a 1952 CA article, Hammond and Horn1 noted The discoveries of the last decade in lung cancer re-

the limitations of retrospective case-control studies in search represent a breakthrough in the truest sense.”7

establishing the hazards of smoking. Two years later, Cokkinides et al8 reported that the prevalence of

citing preliminary evidence from what came to be cigarette smoking among persons in the United States

known as the Hammond-Horn study, Hammond age 18 years and older for the year 2008 was 20.5%,

predicted that “…it may turn out that cigarette smok- representing an approximate halving of the 42%

ing not only greatly increases the probability of devel- smoking rate observed in 1965. This accomplishment

oping lung cancer but also markedly increases the is the result of a large and diverse body of basic science,

death rate from other causes.” Hammond also antici- clinical, and public health research and the application

pated the difficulty of changing smoking behavior: of evidence-based interventions. Much has been

“…it is by no means easy for heavy smokers to give up learned about the pharmacology and psychology of

the habit or even to cut their consumption down to a nicotine addiction, leading to effective use of behav-

moderate level. Furthermore, it is amazing to see how ioral interventions, nicotine replacement, and non-

little effect danger sometimes has as a deterrent to nicotine medications in smoking cessation.9,10 There

people doing what they want to do…”2 has also been tremendous progress in developing pub-

Powerful economic and political forces sought to lic health and policy interventions such as health edu-

further confuse the issue, as illustrated in the March/ cation, excise taxes, cessation support services,

April 1958 issue of CA, devoted entirely to lung cancer legislation to reduce youth access to tobacco products,

epidemiology. This featured a summary of results and clean indoor air legislation.8,11-14

from the Hammond-Horn study, which found lung Despite this substantial progress, economic and po-

cancer death rates of 3.4 per 100,000 man-years in litical factors remain, as Hammond predicted, a sub-

never smokers compared with 157.1 in current smok- stantial barrier to eliminating the leading cause of

ers of at least one pack of cigarettes daily.3 It quoted death from cancer worldwide, and the global burden

Dr. Leroy Burney, then the Surgeon General of the of deaths from cancer and other diseases related to

United States, saying “…the Public Health Service smoking continues to rise.

346 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

EDITORIAL

Not all population segments have benefitted equally amply supplied by the large number of carcinomas in

from tobacco control interventions; individuals with situ of the cervix, which are uncovered by the general-

lower income and less education are more likely to ized use of this method. The thorough study of this

initiate tobacco use during adolescence and less likely material will lead us to the formulation of more exact

to quit successfully. There is evidence that the tobacco criteria for early neoplastic change supplementing the

industry targets low-income and minority communi- well-established criteria based on the more advanced

ties to influence smoking-uptake patterns. Tobacco stages.”16 Five years later, Papanicolaou predicted the

control organizations are now seeking to reduce dis- profound impact of his method on cervical cancer

parities in tobacco use and its health consequences by mortality: “Looking into the future, one may find

developing and implementing initiatives for these great encouragement in the warm-hearted support

populations.8 and endorsement given to cytologic research by the

Although a review of cancer risk factors is beyond Public Health Service and the American Cancer Soci-

the scope of this editorial, it is notable that the epide- ety. Their farsightedness in sponsoring mass screening

miologic strategies used during the 1950s to recognize projects and their unrelenting efforts to arouse public

tobacco as a carcinogen have been very successfully interest and to expedite education and training in this

applied to identify many other risk factors for cancer special field hold great promise that at least one form

and other chronic diseases and to demonstrate that of cancer, that of the uterine cervix, may eventually be

socioeconomic gradients exist in exposure to other risk controlled and its death potential substantially re-

factors. Moreover, comprehensive tobacco control duced, if not fully eradicated. This, if accomplished,

strategies can serve as a model for addressing many will be the realization of a dream, which only a few

other risk factors.15 years ago would have had to be regarded as a

Utopia.”19

It has been estimated that perfect adherence to cer-

Early Detection: The Papanicolaou Test vical cytology screening every 1 to 3 years can reduce

With a few notable exceptions, early cancer detection the incidence of invasive cervical cancer by more than

during the 1950s referred largely to prompt recogni- 90%, but that because of incomplete adherence, the

tion of signs and symptoms. During that period, ACS actual reduction in cervical cancer mortality after the

public education regarding early detection stressed introduction of cervical cytology screening in several

awareness of the “7 warning signs of cancer.” This ap- North American and European populations has var-

proach was the best available at the time, and there is ied from 20% to 60%.20 The Pap test remains among

little doubt that it permitted curative local therapy in the current ACS recommendations for the early de-

some cases, and in others may have extended survival. tection of cancer. The most recent ACS guideline up-

Unfortunately, few cancers recognized by blood- date, in 2002, added testing for human papillomavirus

tinged sputum or changes in bowel habits were curable (HPV) DNA as a screening option in combination

with therapies of that era. with cervical cytology among women aged older than

It was during this decade that the Papanicolaou 30 years, and a 2007 ACS prevention guideline dis-

(Pap) test was vigorously promoted and widely ac- cussed HPV vaccination for cervical cancer

cepted, and CA featured 4 articles by George N. Papa- prevention.21,22

nicolaou between 1952 and 1957,16-19 as well as Although we possess the technology to virtually

additional articles by other cytologists, gynecologists, eliminate death from cervical cancer, consistent im-

and other clinicians. In a 1952 review, Papanicolaou plementation of evidence-based screening remains

explained that “In reviewing the present status of ex- only a dream in many low-resource nations and a work

foliative cytology it appears that its greatest contribu- in progress even for North America and Europe.

tion to science and to humanity is that it has furnished Within the United States alone, substantial variation

us with the means of detecting cancer in its incipiency. is observed in Pap test use among population seg-

Thus, we are provided not only with the chance of ments, and the most powerful predictors of whether

attacking cancer while it still may be amenable to an American woman receives age-appropriate cervical

treatment but also with the material for the study of its cancer screening are educational level and health care

earlier developmental stages. Such material is now insurance coverage.23

VOLUME 60 ⱍ NUMBER 6 ⱍ NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2010 347

Sixty Years of CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

EDITORIAL

The Utopian cancer screening test, with near- Hamilton explained that “Our increasing knowl-

perfect sensitivity and specificity, that can be per- edge of nucleic acids has been a major factor in dissi-

formed with minimal morbidity and cost, and that pating the pessimism that has long shrouded the

permits curative treatment for asymptomatic lesions, search for cancer-controlling chemicals. The nucleic

still eludes us in 2010. Several current guideline- acids have thus not only removed a long standing psy-

recommended tests, albeit imperfect, have not closely chological barrier but also have provided an important

approached their lifesaving potential because of insuf- practical basis for cancer chemotherapy…The natural

ficient, uneven, and imperfect utilization.23 sciences are essentially empirical and the science that

In a 1953 commentary, Hammond noted that can- underlies cancer chemotherapy is no exception. Thus

cer screening had not yet been proved to reduce cancer aminopterin and amethoptenin, antagonists of folic

mortality. He further suggested that some neoplasms acids, were found to be useful palliative agents in the

reach an incurable stage before they are detectable by treatment of acute leukemia in children before any

current screening tests, that others will remain curable knowledge of the intimate mechanism of their che-

even after reaching a size that is obvious without motherapeutic effect had been achieved.” Anticipat-

screening, and that the most relevant subset is com- ing the future of cancer biology and pharmacology,

prised of asymptomatic lesions detectable by screen- Hamilton suggested that “Just as the chemical formu-

ing that are still curable.24 Hammond’s comments lation of the building blocks of DNA has permitted

foreshadowed much of the current controversy con- the design of antagonists for these building blocks, so

cerning overdiagnosis by screening of indolent cancers it is reasonable to expect that this new knowledge of

that would remain clinically insignificant, as well as the arrangement in space of the building blocks of

the increasingly sophisticated epidemiological meth- DNA and the impressive possibilities for determining

ods now used to develop evidence-based screening the site of DNA specificity will provide a new target

guidelines.23 for ‘rational cancer chemotherapy.’”26 Thus began the

gradual transition of cancer pharmacology from em-

pirical endeavors such as screening natural products

Treatment: Chemotherapy for in vitro cytotoxicity to the design of drugs based on

Several important CA articles published during the an intimate understanding of molecular anatomy and

1950s reviewed the contemporary standards of care in physiology. Although today we tend to exclude cyto-

surgical oncology and radiation oncology and the toxic drugs from the category of targeted therapies,

value of these modalities in the palliation and cure of one could reasonably view the breakthroughs in nu-

cancer. In retrospect, however, perhaps the 2 most in- cleic acid chemistry and biology of the 1950s as key

teresting CA articles on cancer treatment from that events in early targeted therapies. Following this line

decade were juxtaposed in the September/October of reasoning, the difference between targeted thera-

1955 issue. One article, by Karnofsky, reviewed the pies of the 1950s and those of the current decade is

current status of cancer chemotherapy, and the sec- that the former were mostly aimed at pathways of nu-

ond, by Hamilton, discussed the relevance of DNA to cleic acid metabolism and gene structure whereas the

medical oncology.25,26 latter generally target pathways that regulate cell pro-

We hope and expect that cancer drugs in use 50 liferation and survival.

years from now will be far more effective and safer It seems notable in retrospect that initial clinical

than today’s cytotoxic chemotherapy. However, this studies of cytotoxic chemotherapy did not produce any

modality has contributed greatly to the survival of mil- cures and provided rather brief responses, but the

lions of patients during the past half century, and its combination of basic and clinical research over several

role in oncology is likely to continue for the foresee- decades incrementally improved the efficacy, con-

able future. In 1955, Karnofsky wrote that “Since the trolled the toxicity, and refined the indications for this

beneficial results of chemotherapy are thus only partial modality. Some forms of cancer (such as Hodgkin dis-

and temporary, with resistance ultimately appearing, ease, germ cell cancer of the testis, acute lymphoid

it is hoped that a combination of several chemothera- leukemia, and some types of non-Hodgkin lym-

peutic agents may produce a longer therapeutic re- phoma) are now frequently cured by cytotoxic chemo-

sponse or actually cure the disease.”25 therapy alone; other forms are occasionally curable;

348 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

EDITORIAL

and, for many others, cytotoxic chemotherapy makes a issue of CA, by Finesinger et al,31 described a series of

substantial contribution (often in combination with interviews with 72 oncology patients, revealing rather

other modalities) to curative therapy, extending sur- shocking attitudes and beliefs about cancer. They re-

vival, and palliating symptoms.27 The current diversity ported that “These feelings of guilt–it is my fault that I

of pharmacologic approaches targeting membrane- have cancer; I must have done something wrong– oc-

bound receptor kinases, intracellular signaling kinases, curred in every one of our patients. Many patients re-

epigenetic abnormalities, protein dynamics, and tu- act to cancer as they would to venereal disease–‘It is

mor vasculature and microenvironment and the foul,’ ‘I am ashamed to have it,’ ‘I am ashamed to talk

rational precision of their design are impressive prod- about it.’” Denial was a common behavioral defense

ucts of decades of basic research.28 With few excep- mechanism: “…the behavior in at least two thirds of

tions, these agents have not yet yielded the cures that the cases showed clear evidence of avoiding facing

preclinical studies led us to hope for. Only time, pa- their problem realistically…” and “A few (five pa-

tience, and perseverance will reveal whether today’s tients) actually denied that they had a cancer, attribut-

new classes of drugs follow a similar trajectory as cli- ing their symptoms to other causes. Many others

nicians learn to optimally combine them with one an- (twenty-six) denied the gravity of their situation by

other and with other modalities. displaying an unnatural lack of concern…” They con-

sidered the views of this 56-year-old woman with in-

operable breast cancer to be representative: “It’s not

Clinician-Patient Communication: like heart trouble because it is such a dirty disease–so

Prognostic Disclosure unclean–repellent. In the end there is an odor– often

Given the poor prognosis associated with a cancer di- there is deformity. People fear contagion. They don’t

agnosis during the 1950s, the attention to end-of-life like to be with cancer patients. You can not know how

care in CA articles during that decade is not surprising. awful it is. In the past when I had known people had

What does seem remarkable, particularly when cancer, I always felt so badly for them. Heart disease is

viewed in the context of current ethical views, is that not unclean. People don’t object to being with these

the wisdom of diagnostic and prognostic disclosure people. It’s all my fault too. I must have done some-

was frequently debated in CA, and that authors often thing to deserve all this.” They conclude with the fol-

recommended against disclosure. In the January/Feb- lowing advice: “How much of the truth should we tell?

ruary 1953 issue, Spencer and Laszlo focused on treat- From the strict operational point of view the answer

ment options for patients with advanced cancer but would be all that is necessary to achieve the goal of

also addressed the following question: “Should the pa- therapy. In some patients more information is neces-

tient be told his diagnosis and prognosis? This is a very sary than in others. We have found this operational

controversial topic and no fixed answer is applicable to rule useful in many difficult problems. Our job is not

all patients. However, it seems that the physician and to make psychiatrists, psychologists, pathologists, or

responsible members of the family can bear the burden surgeons of our patients. It is to supply them with

of the diagnosis and prognosis better than the patient. enough practical information to help them use the

The fear associated with this disease in the minds of best available therapy with the minimal personal dis-

the public is sometimes so great that acute depressions turbance. We need not tell the whole truth but what-

and suicidal attempts have followed the disclosure of ever we say should be truthful.”31

such information. Furthermore, there seems no ap- During the past 5 to 6 decades, our attitudes toward

parent advantage to the patient in burdening him physician-patient communication and prognostic dis-

with this knowledge. If the symptoms are explained closure have changed as dramatically as, and perhaps

to him in terms other than cancer and a concise plan as a result of, the concomitant progress in under-

of management is offered, difficulties are rarely standing, detecting, and treating cancer. Delivering

encountered.”29 appropriate information and delivering information

In considering this topic, it is difficult for us to avoid appropriately are now recognized as essential skills for

what historians call the bias of presentism (“an atti- oncology care professionals. The importance of this

tude toward the past dominated by present-day atti- skill in optimizing patient choices regarding treat-

tudes and experiences”30). Another article in the same ment, and especially so regarding end-of-life care, as

VOLUME 60 ⱍ NUMBER 6 ⱍ NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2010 349

Sixty Years of CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

EDITORIAL

well as reducing distress among patients and their 9. Henningfield J, Fant R, Buchhalter A, Stitzer M. Pharmacotherapy

for nicotine dependence. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:281-299.

families has been emphasized in several recent CA 10. Hurt RD, Ebbert JO, Hays JT, McFadden D. Treating tobacco depen-

reviews.32-35 Studies have demonstrated that frame- dence in a medical setting. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:314-326.

11. Sargent JD, DiFranza JR. Tobacco control for clinicians who treat

works such as SPIKES (Setting, Perception, Invita- adolescents. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:102-123.

tion, Knowledge, Empathy, and Strategize) and 12. Cokkinides V, Bandi P, Ward E, Jemal A, Thun M. Progress and op-

portunities in tobacco control. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:135-142.

NURSE (Naming, Understanding, Respecting, Sup-

13. Eriksen M, Chaloupka F. The economic impact of clean indoor air

porting, and Exploring) can facilitate prognostic dis- laws. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:367-378.

closure and responding to patients’ reactions to that 14. Glynn T, Seffrin JR, Brawley OW, Grey N, Ross H. The globalization

of tobacco use: 21 challenges for the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin.

information, and that training in these and other tech- 2010;60:50-61.

niques can improve communication effectiveness and 15. Yach D, McKee M, Lopez AD, Novotny T. Improving diet and physi-

cal activity: 12 lessons from controlling tobacco smoking. BMJ.

reduce provider burnout.32-33 2005;330:898 –900.

16. Papanicolaou GN. Present status and future trends of exfoliative cy-

Conclusions tology. CA Cancer J Clin. 1952;2:50-56.

17. Papanicolaou GN. The value of exfoliative cytology in the diagnosis

We have undertaken this brief historical activity in and control of neoplastic disease of the breast. CA Cancer J Clin.

1954;4:191-197.

part as a celebration of our journal’s longstanding role

18. Papanicolaou GN. Exfoliative cytology in research and diagnosis. CA

in providing valuable information about cancer to cli- Cancer J Clin. 1956;6:190-195.

nicians. In so doing, however, we have been pro- 19. Papanicolaou GN. The cancer-diagnostic potential of uterine exfoli-

ative cytology. CA Cancer J Clin. 1957;7:124-135.

foundly touched by this reminder of the courage, 20. Berg AO. Screening for Cervical Cancer: Recommendations and Ra-

determination, and inspiration with which patients, tionale. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research;

2003. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/cervcan/

clinicians, and scientists confronted the bleak reality cervcanrr.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2010.

of cancer during the 1950s. Public health without to- 21. Saslow D, Runowicz CD, Solomon D, et al. American Cancer Society

guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA

bacco control or medical oncology before recognition Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:342-362.

of the double helix seems shockingly primitive by to- 22. Saslow D, Castle PE, Cox JT, et al. American Cancer Society guide-

line for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine use to prevent cervical

day’s standards. It is our prediction and our sincere cancer and its precursors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:7-28.

23. Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer

hope that future retrospection will reach the same screening in the United States, 2010: a review of current American

conclusions regarding cancer control and clinical on- Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer

J Clin. 2010;60:99-119.

cology practices of this decade, and that information 24. Hammond EC. Early diagnosis and cancer cure rates. CA Bull Cancer

in this journal will continue to assist clinical and public Prog. 1953;3:175-176.

25. Karnofsky DA. Chemotherapy of cancer. CA Bull Cancer Prog.

health professionals, as it has for the past 60 years, in 1955;5:165-173.

diminishing and eventually eliminating the burden of 26. Hamilton LD. Cancer chemotherapy and the structure of DNA. CA

Bull Cancer Prog. 1955;5:159-164.

cancer on individuals and society. 27. Freter C, Perry M. Systemic therapy. In: Abeloff M, ed. Abeloff’s Clinical

Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2008:453-463.

References 28. Ma WW, Adjei AA. Novel agents on the horizon for cancer therapy.

CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:111-137.

1. Hammond EC, Horn D. Tobacco and lung cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 29. Spencer H, Laszlo D. Problems in the management of patients with

1952;2:97-98. advanced cancer. CA Bull Cancer Prog. 1953;3:14-18.

2. Hammond EC. The place of tobacco in the etiology of lung cancer. CA 30. Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Presentism. Available at:

Bull Cancer Prog. 1954;4:49-53. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/presentism. Accessed

3. Anonymous. Lung cancer death rates in relation to smoking. CA Bull August 8, 2010.

Cancer Prog. 1958;8:42-43. 31. Finesinger JE, Shands HC, Abrams RD. Managing the emotional

4. Burney LE. Lung cancer and excessive cigarette smoking. CA Bull problems of the cancer patient. CA Bull Cancer Prog. 1953;3:19-31.

Cancer Prog. 1958;8:44. 32. Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA, Fryer-Edwards K. Ap-

5. Little CC. The public and smoking: fear or calm deliberation? CA Bull proaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer

Cancer Prog. 1958;8:49-52. J Clin. 2005;55:164-177.

6. Rutstein DD. An open letter to Dr. Clarence Cook Little. CA Bull Can- 33. Chochinov HM. Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end-

cer Prog. 1958;8:46-48. of-life care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:84-103; quiz 104-105.

7. Davies DF. A statement on lung cancer. CA Bull Cancer Prog. 34. Christ GH, Christ AE. Current approaches to helping children cope

1959;9:207-208. with a parent’s terminal illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:197-212.

8. Cokkinides V, Bandi P, McMahon C, Jemal A, Glynn T, Ward E. To- 35. Finlay E, Casarett D. Making difficult discussions easier: using prog-

bacco control in the United States–recent progress and opportuni- nosis to facilitate transitions to hospice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:

ties. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:352-365. 250-263.

350 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Cancers 13 01521 v2Document20 pagesCancers 13 01521 v2Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Molecular Identification Methods of Fish Species RDocument30 pagesMolecular Identification Methods of Fish Species RRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- CancersDocument13 pagesCancersRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Yusup 2020 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 429 012046Document9 pagesYusup 2020 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 429 012046Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- DNA Barcoding As A Tool For Coral Reef ConservatioDocument14 pagesDNA Barcoding As A Tool For Coral Reef ConservatioRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Search ResultsDocument28 pagesSearch ResultsRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- MS 255 Assignment1Document3 pagesMS 255 Assignment1Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Ulfah 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 674 012032Document6 pagesUlfah 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 674 012032Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer ResearchDocument23 pagesJournal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer ResearchRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Lancet OncologyDocument8 pagesLancet OncologyRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Radiotherapy and OncologyDocument12 pagesRadiotherapy and OncologyRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Tfap2A Potentiates Lung Adenocarcinoma Metastasis By A Novel Mir-16 Family/Tfap2A/Psg9/ Tgf-Β Signaling PathwayDocument13 pagesTfap2A Potentiates Lung Adenocarcinoma Metastasis By A Novel Mir-16 Family/Tfap2A/Psg9/ Tgf-Β Signaling PathwayRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 4 - Clinical Cancer ResearchDocument4 pages4 - Clinical Cancer ResearchRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 3 - Nature Reviews Clinical OncologyDocument8 pages3 - Nature Reviews Clinical OncologyRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 9 - Journal of CarcinogenesisDocument6 pages9 - Journal of CarcinogenesisRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- 5 - Molecular CancerDocument6 pages5 - Molecular CancerRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Physics Trivia QuestionsDocument3 pagesPhysics Trivia QuestionsRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Pabello - Conceptual Questions On MagnetismDocument1 pagePabello - Conceptual Questions On MagnetismRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- DOST Scholarship FormDocument3 pagesDOST Scholarship FormRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Exercises On DefinitionDocument1 pageExercises On DefinitionRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 11 - Molecular OncologyDocument15 pages11 - Molecular OncologyRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Current and Resistance ExerciseDocument2 pagesCurrent and Resistance ExerciseRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- War of CurrentsDocument2 pagesWar of CurrentsRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

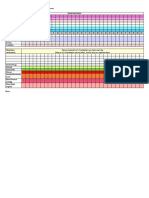

- DAILY MOOD CHART: MONTH OF - : High +3 +2 +1Document2 pagesDAILY MOOD CHART: MONTH OF - : High +3 +2 +1Rhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Role of Humanities and The Arts in 21st Century EducationDocument2 pagesThe Role of Humanities and The Arts in 21st Century EducationRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Pabello - Conceptual Questions On MagnetismDocument1 pagePabello - Conceptual Questions On MagnetismRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Pabello, Rhaiza P. April 28, 2020 Internet Exercise C1A1-YDocument3 pagesPabello, Rhaiza P. April 28, 2020 Internet Exercise C1A1-YRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Physics 2 ECQ Quiz 1 - Current and ResistanceDocument2 pagesPhysics 2 ECQ Quiz 1 - Current and ResistanceRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Pabello - ECQ Quiz 1 - Current and ResistanceDocument3 pagesPabello - ECQ Quiz 1 - Current and ResistanceRhaiza PabelloNo ratings yet

- Ob Case Study Intro PageDocument3 pagesOb Case Study Intro Pageapi-314637591No ratings yet

- 2018 - BMJ - GUIA - Suicide Risk ManagementDocument63 pages2018 - BMJ - GUIA - Suicide Risk ManagementPAULANo ratings yet

- Clinical Audit On Diabetic Retinopathy ScreeningDocument1 pageClinical Audit On Diabetic Retinopathy ScreeningJeffrey Elvin100% (1)

- Screening For Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy-1Document8 pagesScreening For Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy-1AANo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening Through Visual Inspection With Acetic AcidDocument10 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening Through Visual Inspection With Acetic AcidIJPHSNo ratings yet

- DK-The British Medical Association-Complete Family Health GuideDocument992 pagesDK-The British Medical Association-Complete Family Health Guidedangnghia211290% (10)

- UICC Annual Report 2005Document44 pagesUICC Annual Report 2005schreamonn5515No ratings yet

- Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Breast Self Examination Among Secondary School TeachersDocument6 pagesKnowledge Attitude and Practice of Breast Self Examination Among Secondary School TeachersRasman RaufNo ratings yet

- Framework Version2 FINAL Dec052022Document62 pagesFramework Version2 FINAL Dec052022Ana SeverinaNo ratings yet

- BRS PediatricsDocument681 pagesBRS PediatricsVictoria SandersNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Abu Dhabi Health Statistics 2017Document51 pagesAbu Dhabi Health Statistics 2017Sehar ButtNo ratings yet

- CAM ToolkitDocument81 pagesCAM ToolkitEdwin WijayaNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care For Resilient Health Systems in Latin AmericaDocument220 pagesPrimary Health Care For Resilient Health Systems in Latin AmericaN LNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Progression To Referable Diabetic.11Document11 pagesRisk Factors For Progression To Referable Diabetic.11library SDHBNo ratings yet

- Morley Et Al 2015 PDFDocument24 pagesMorley Et Al 2015 PDFNinda NurkhalifahNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three Research Methodology Study DesignDocument3 pagesChapter Three Research Methodology Study Designotis2ke9588No ratings yet

- How Is Equity Captured For Colorectal, Breast and Cervical Cancer Incidence and Screening in The Republic of Ireland: A ReviewDocument17 pagesHow Is Equity Captured For Colorectal, Breast and Cervical Cancer Incidence and Screening in The Republic of Ireland: A Reviewdadidida22No ratings yet

- Delna Handbook PDFDocument20 pagesDelna Handbook PDFGopal KrishanNo ratings yet

- Referral To Community Care From School-Based Eye Care Programs in The United StatesDocument10 pagesReferral To Community Care From School-Based Eye Care Programs in The United StatesAyu MarthaNo ratings yet

- Worldwide Burden of Colorectal Cancer: A ReviewDocument5 pagesWorldwide Burden of Colorectal Cancer: A ReviewRomário CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- UICC Annual Report 2006Document44 pagesUICC Annual Report 2006schreamonn5515No ratings yet

- May 5, 2017 Strathmore TimesDocument28 pagesMay 5, 2017 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNo ratings yet

- Chamberlin 2021Document14 pagesChamberlin 2021EthanNo ratings yet

- Helicobacter Pylori EradicationDocument190 pagesHelicobacter Pylori EradicationMaca Vera RiveroNo ratings yet

- WCLC2021 Abstract Book - Final 16310719983133277Document1,066 pagesWCLC2021 Abstract Book - Final 16310719983133277Shawn Gaurav Jha100% (1)

- Breast Self Examination Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesBreast Self Examination Literature Reviewcjxfjjvkg100% (1)

- Biology Project CancerDocument20 pagesBiology Project CancerJay PrakashNo ratings yet

- Wongs Essentials of Pediatric Nursing 9th Edition Hockenberry Test BankDocument4 pagesWongs Essentials of Pediatric Nursing 9th Edition Hockenberry Test BankPeter Strange100% (26)

- BusinessPlan Template 2013Document17 pagesBusinessPlan Template 2013safeerkkNo ratings yet

- The Monthly Lifeline of The Fiji Cancer Society 2018Document18 pagesThe Monthly Lifeline of The Fiji Cancer Society 2018Grace TuvakasigaNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (403)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (20)