Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Poverty and Natural Resource PDR

Uploaded by

MahnoorCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Poverty and Natural Resource PDR

Uploaded by

MahnoorCopyright:

Available Formats

Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad

Poverty and Natural Resource Management in Pakistan

Author(s): Muhammad Irfan

Source: The Pakistan Development Review, Vol. 46, No. 4, Papers and Proceedings PARTS I and

II Twenty-third Annual General Meeting and Conference of the Pakistan Society of

Development Economists Islamabad, March 12-14, 2008 (Winter 2007), pp. 691-708

Published by: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41261190 .

Accessed: 20/06/2014 22:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Pakistan Development Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

©ThePakistanDevelopment Review

46 : 4 PartII (Winter2007) pp. 691-708

Povertyand NaturalResource

Managementin Pakistan

Muhammad Irfan

Pakistan is a countryof contrasts,with diversifiedrelief having majestic high

mountainranges snow-coveredpeaks, eternalglaciers, and the inter-mountain valleys in

the north.Irrigatedplains in the Indus basin contrastwithstarkdesertsand rugged rocky

plateaus in southwest Balochistan. The countryis arid and semi-arid with substantial

variationin temperaturedependingupon the topographyand characterisedby continental

type of climate. Over the years since independence the naturalresources of the country

(land and water) have been harnessedwhich in turnmade it possible to feed the growing

population which more than quadrupled during the past sixty years. Constructionof

Tarbela and Mangia Dam facilitated the growth of irrigatedagricultureand led the

croppingintensityto peak. Sectors otherthan the agriculturealso developed because of

the backward and forwardlinkage of the agriculturalgrowththerebyhaving an economy

diversifiedand much less dependenton agriculture.

There are however concerns raised with respect to the costs and practices of the

past developmentin termsof environmentaldegradation,resource misuse and depletion.

One fourthof the country'sland area, suitable forintensiveagriculturesuffersfromwind

and water erosion, salinity/sodicity,water logging, floodingand loss of organic matter.

Deforestationhas taken its toll as the accelerated surfaceerosion is shorteningthe life of

Tarbela and Mangia reservoirs,which provide waterfor90 percentof the food and fibre

productionin the country. Over-exploitationand misuse of rangelandsextendingover a

vast area are seriouslyconstraininglivestock production,therebyadversely affectingthe

livelihood of pastoral communities. The mangrove areas are under increased

environmentalstress.

Overexploitationand misuse of the resources by the population in the contextof

the development has not been fullyreckoned by the researchersas well as the policy

makers.Given the factthathealthyecosystemsproduce the requirementsforlife which in

turnhighlightthe crucial linkages between the society and eco-systems. The complex

relationshipsbetween managementof natural sources and survival strategyof poor are

not fullyexamined and investigatedin Pakistan. This is despite the fact that poor rely

moreon naturalresourcesthanthe rich. Unfortunately few, if any,researchendeavour in

Pakistan has been conducted to unravel the nexus between the poverty and natural

MuhammadIrfanis Professorof Economicsat the International Instituteof Islamic Economics,

International

IslamicUniversity,

Islamabad.

Author'sNote: The authoris thankful

to the Asian DevelopmentBank forits generousfundingto

completethisstudy.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

692 MuhammadIrfan

resourcemanagement. This is not to suggestthatthe environmental degradationand

threatened is

biodiversity glossed over. In fact it is the opposite wherein relevant

organisationsand ministriesare continuously assessing thesechanges. What needs to be

highlighted is that the poverty reduction and resource management have not been

examinedin an interdependent framework of environment, development and population

growth.This in turnwouldhave led to mounting of variouscase studiesfocusingupon

theseinterlinkages. Exclusive focus of the developmentagenda on attainingthe UN

MillenniumDevelopmentGoals as well as ensuingWB PovertyReductionStrategy

Papers tendedto relegatethe importance of the examinationof cruciallinksbetween

resourcesmanagement, environment and povertyreductionto the secondaryposition

whereinmonitoring and estimation of povertylevelsas well as thesafetynetsto address

thecasualtiesof growthin thecontextof globalisationappearsto have been accorded

forresearchandevaluationexercisesas wellas datacollection.

priority

In thisexercisean effort is made thoughin a limitedway because of thelack of

requisitedata to fillthisvoid. Povertylevels and trendsforthecountryand therural

urbanregionsare describedin the firstsectionof thisreport,whichis followedby a

discussionoftheoveralleconomicgrowth (GDP) anditsdistribution to discernitsimpact

on povertysituation. The relationship betweentheutilisation of majornaturalresources

of thecountry thelandwater,poverty is studiedin thethirdsectionwhereinthemapping

of povertyto different agroclimatic zones is attempted. Sourcesof incomeby poverty

statuscontrolling the othervariablesare discussedin the fourthsection.The role of

in povertyreduction

agricultural is also assesseddiscerning thepovertylevelsin thefifth

section.The finalsectionroundsup thediscussionas wellas offerssomesuggestions for

datacollectionto sharpenourunderstanding abouttheinterlinkages betweenpoverty and

resourcemanagement.

I. POVERTY PROFILE

Multidimensional of povertydefies a neat demarcation.Oftenseveral but

not separable meanings can be attributedto povertywhich essentially should

encompass totalityof deprivationexperienced by an individual or group of

individuals.Encyclopaediaof Social Sciences forinstance,suggeststhatdefinition

of

poverty is convention specific and distinguishesbetween Social Poverty and

Pauperism.The formerincludes economic inequalityor propertyincomes etc in

additionto social inequalitysuch as dependenceor exploitationwhile Pauperism

denotesones inabilityto maintainat the level conventionallyregardedas minimal.

Pauperism has been the focus of researchersin Pakistan and elsewhere in the

developingworld, whereineffortshave been made to quantifythe poverty,thus

defined,usingessentiallyarbitrary povertylinesor normswithapplicationof varying

procedures forestimation. the

During past varietyof procedureswereused. Planning

Commissionof Pakistanhoweverin 1998-99 suggestedan officialpovertyline in

termsof minimumcaloric requirementper adult (2350 per day) and the needed

expenditureof Rs 670 per personforthatyear.Despite the need to demonstrate the

relevance of this caloric requirementthe constructedpovertyline can facilitate

monitoring thepovertylevels in thecountrywhichhas assumedimportancegiventhe

global emphasison MDGs and Social SafetyNets.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 693

Thereis almosta consensusthatin an historical perspectivePakistanwas successful

in reducing povertyover thedecades since independence. Absolute poverty, Head Count

ratiobasedon caloricintake, declinedfrom46.5 percent in 1969-70to 17 percentin 1987-

88. Since thenthereversalhas takenplace till2001 whenit rose to 34 percent.Recent

research exercisesfortheperiodsince2002 aresuggestive of improvement, according tothe

Government - around10 percent pointdeclinein poverty incidence,whichis contested by

independent researchers includingthe WB which claim thatpoverty level may have

declinedfrom34 percent in2001 to29 percent in2004-05 Itis extremely difficult

tooffer a

firmconclusionabout the currentpoverty levels in Pakistan but theofficialclaim of 10

percentpointdeclineduringthethreeyearsperiodmustbe supported by otherindicators

suchas sharpriseinrealwages,massivereduction intheinequality andunemployment rates.

The generalimpression as well as our findings is thatthesevariablesfailto supportthe

official

claim.

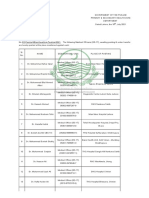

For the periodsince 1998 threedifferent estimatesare presentedin Appendix

Tables 1, 2, and 3. Alongwiththeofficialestimateswhichsuggesta 10 percentpoint

declinein thepoverty from34 percentin 2001-02to 23 percentin 2004-05,theestimates

fromtheWorldBank whichuses Surveybased priceindexrathertheofficialCPI and

Jamal(2007) whoestimatesCalorieConsumption Function(CCF) andprovidesa longer

timetrend,howeverindicatethatthepovertyin thelatteryeardeclinedto 30 percent.

Jamalalso suggestthattherural/urban gap in thepovertylevel has narrowed, in other

wordspovertydeclinewas largerin ruralareas thanin urbanareas,theresultdifferent

thantheothertwoexercises.Juxtaposition ofthesethreestudiesis suggestive of at besta

stagnation of the povertylevels witha quantumjump in 2001-02 because of drought

particularly in Sindhprovinceand thenreversalsin thepovertytrendto 1998-99levels

also in thesame province.The officialclaimof drasticcurtailment in povertylevels in

2004-05to 24 percentmeritsfurther It

scrutiny. may be added thataround 10 percentof

thehouseholdslie withinthe rangeof ±5 percentof the povertyline, hence a minor

changein the povertyline, inflationary adjustment and data protocolprocedurescan

generate substantial intheestimated

variations incidenceofpoverty.

Regionaland ProvincialPovertyIncidence

Invariablyall theresearchexerciseson estimationof povertyconcurthatpoverty

levelsare higherin ruralareasthanin theurban(see Tables 1, 2 and 3). Giventhatthe

ruralpopulationaccountsfortwo thirdsof thetotal,majority of thepoor live in rural

Pakistanandpoverty is a ruralphenomenon.Accordingto theofficialestimatesthehead

countratioof poor in ruralareas is almostdoubleof theurbanareas in 2004-05. The

WorldBankstudysuggestsalso similarmagnitudes of theruralurbangap,thoughJamal

differson thegap betweenurbanand ruralareas.These researchexercisessuggestthat

poverty is predominantly a ruralphenomenon becausetwo-thirdsof thepopulationslive

inruralareas.

ProvincialPovertyProfile

Fourprovinces, whichalso coincideswith

mostlydefinedon thebasis of ethnicity

resourceendowments

natural ThusPunjaband Sindhprovinces

oftenclassifythecountry.

haverichagricultural

resourcebaseas wellas botharemoredevelopedcompared toresource

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

694 MuhammadIrfan

poorandlessdevelopedprovinces ofNWFP andBalochistan. Theprovincial povertypicture

is depictedinAppendix Table4. Application ofcareis counseledintheinterpretation

ofdata

because theHIES data are notregardedas representative at thelevel of province.Two

estimates,one fromtheWorldBankandtheotherbyAnwar(2006) provided inthetableare

indicativeof thefindings thatin generalpoverty incidenceat theprovinciallevelstendto

fluctuate.WhileBalochistanwas least poor in 1998-99,a statusacquiredby Punjabin

2001-02andSindhin2004-05.Further classification

intermsofurbanandruralareastends

to suggestthattheurbanSindhemergedto be theleastpoorforall thethreeyearsunder

study.A closerperusalofthetablealso indicates thatimprovement in poverty situation

was

mostlyconfined to Sindhprovinceduring2001-02to 2004-05,theotherprovinces did not

sharethisgainrather thesituationinBalochistanprovinceworsened during thesameperiod.

PovertyIncidenceat DisaggregatedLevels

To a largeextentthedichotomy of urbanand ruralareasfailsto reckonwiththe

continuum obtainedat ground.Ruralareasareintegrated withnearbyurbancentres because

of boththefactorand productmarket Similar

interdependence. interlinkages existbetween

smalltownsand majorurbancentres.In otherwords,neither theurbanareasnortherural

areasarehomogenous units.Urbanareasincludemajortownsandsmalltowns.Based on

householdlevel (raw data) one findsthatthemajorurbancentres(classifiedby Federal

Bureauof Statistics as selfrepresentingbecauseof largepopulation sizes andtheprovincial

capitals)are in a very comfortable situationwhere the poverty incidence (usingofficial

poverty line)in 2004-05 was 9.7 In

only percent. contrast theotherurbanareaswerecloser

to ruralareaswherethepercentages of poorwere22.1 percent and28 percent respectively.

Withintheruralareasnon-farm populationwas worsthitbyregistering 34 percent pooras

compared to 23 percentof thepopulation of farm households. In terms of the provincial

comparison substantial differential

persistswherein majorurbancentresof Sindhappearto

be leastpoor(6.2 percent)comparedto 20.6 percentof NWFP. In an overallcomparison,

NWFP can be regardedas the mostpoor (see AppendixTable 5). Major urbanareas

particularlyin SindhandPunjabprovinces weretheoneswhichexperienced industrial

and

commercialdevelopment, hence a lower level of povertyis plausible.The above

disaggregated descriptionof povertyincidenceis indicative

of theclose similarity between

ruralareasand smallurbanareas.The latterappearsto be theextension of theformer with

mushroom growth oflessproductiveinformal sectorenterprises.

II. GDP GROWTH AND POVERTY

Admittedly, overalleconomicgrowthhas a directbearingon povertylevel in a

country,however, Pakistan'sexperiencereflects

a dissonancebetweenthesetwoforsome

the For

periodsduring pastsixtyyears. example,highgrowth periodof 1960sis associated

witha declinein povertyonlyin urbanareas.In ruralareas,thepoverty situationworsened.

Duringthenextdecade,GDP growthratewas lowerthanthepreviousone butlevel of

povertydeclinedthoughtheevidenceis sketchy. During1980s,one findsa straightforward

andexpectedrelationshipbetweenGDP growth rateandpoverty levelswherein thepoverty

situation

improved whilethe economyregistereda remarkable growth Duringthe1990s

rate.

thepovertysituationworsened,being24.9 percent in 1992/3

to 32.1 in 2001,becauseoflow

and erraticgrowthprofile,in additionto othersocio-economic and politicalfactors.The

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 595

declinein GDP growthcontinuedtill2003, a periodassociated withstrictimplementation of

Stabilisationand StructuralAdjustmentProgramme. Since 2003 theeconomyappears to have

a turnaroundby registering roughly6 percentGDP growthrateduringthepastfiveyears.

A perusal of researchstudies conductedover the years reflectsthatin addition to

growththere were some importantdeterminants of povertysituation.For instance,high

growthrateof 1960s failedto reflectany improvement in thepovertysituationin ruralareas

because of the evictionof tenantsand rise in landlessness[Man and Amjad (1984)]. In the

wake of subdued economic performanceof the early 1970s, a decline in the povertylevel

was made possible throughescalationin thepublic sectoremploymentand a massive rise in

public sectorexpenditure[Zaidi (1995)]. Similarly,Middle East emigrationand returnflow

of remittances had a positiveinfluenceon GDP growthas well as povertytill late 1980s. In

other words, Pakistan's experience suggests a very close link between employment

generation,remittancesand tightlabourmarketand poverty.To theextentthe improvement

in povertysituationduring1970 and 1980s occurredbecause of the policies and measures

resulting in huge budget deficits and mounting indebtedness,these represent inter-

generationalpovertyshift,wherein futuregenerationshave had to pay back what was

borrowedforsustainingas well as inflating theconsumptionlevel of currentgeneration.

The slippage of the economy into debt traparound late 1980s and reductionin the

foreignaid due to PresslerAmendment,in factput a halt to the past practiceswhereinthe

entiredevelopmentexpenditureand occasionallythecurrentexpenditureused to be financed

by internaland externalborrowing.In orderto rectifythe internaland externalimbalances

throughcurtailingexpenditure,raising revenues and better export performanceunder

IMF/WorldBank reformpackages, the economy was subjected to a discipline. Pakistan

agreed to implementvarious structuraladjustmentand stabilisationprogrammes.It is in

this context that four programmes beginning with 1987-88 were signed by the

Governmentof Pakistan for implementation.With the exception of the last 1999-2003,

there were implementation lapses. Pakistan has been successful in attaining

macroeconomicstabilityby implementingSAP during1999 to 2003 thoughat the.costof

subdued economic performance,squeeze of the developmentexpenditureand worsening

poverty which was also compounded by the erratic weather conditions adversely

affectingthe growthin agriculture,the major sectorof theeconomy.

The deteriorationof the poverty conditions in the country in the context of

StructuralAdjustmentProgrammesduringthe firstfive years of the currentregime was

due to a number of factors which explain poor economic performanceas well as

worseningpovertysituationin the countrytill 2003.. For instance,decline in the GDP

growthrate has been attributedto low level of investmentand lack of effectivedemand

occasioned by the squeeze entailed by massive reductionin the public sectorexpenditure

to address the problemof budget deficit.Furthermorethe failureof the state to bringthe

rich into tax net rendered the taxation structureregressive wherein the poor were

subjected to a disproportionateburden. Similarly,the withdrawalof input subsidies in

agriculturesectoralong withprovisionof internationalprices to producersbenefitedonly

those who had marketedsurplus in the agriculturesector which also explains the failure

of growthin agricultureduring1990s to have a positive influenceon the povertyin rural

areas. Parenthicallyit may be added thatthe growthrate in agricultureis alleged to be an

overestimatefor 1990s.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

696 MuhammadIrfan

In additionthe inequalityin the economyincreasedwhereinthe Gini index

rose from0.26 to 0.30 accordingto Federal Bureau of Statisticsduring1997-98 to

2001-02 (see AppendixTable No. 6). A decompositionexercisesuggeststhatgrowth

effectfor1998-99to 2001-02 in factadded to povertywhileredistribution effectwas

negative.For recentsub-period2001-02 to 2004-05, it was the redistribution effect

whichwas positiveand added to povertylevels whilegrowtheffectwas negative(see

AppendixTable 7).

The conjunctiveinfluenceof tariffrationalisation, financialsectorreformand

privatisation led to closure of factories and downsizing which in turnresultedinto

substantialjob losses.It maybe addedthatpoverty relatedexpenditure ofthegovernment

drasticallyreducedas a percentage of GDP duringthedecade of 1990s till2003 thereby

crucifying the poor at the alterof macrostabilisation. The labourmarketoutcomeas

indexedby risingunemployment rate and stagnantor decliningreal wages also an

offshoot ofthesemeasures,further compounded thesituation.

Whilsttheabove modeof analysisprovidesexplanation forrisein povertyduring

1990s and till 2001-02 thereis also a need to disentanglethe effectof structural

adjustment fromtheinherent limitationof theoveralldispensation of thecountry.Failure

of investment to rise,thebasic factorwhichexplainslow growth, can be attributedto the

inconsistency of thepoliciesalong withlaw and ordersituationand misgovernance but

cannotbe regardedas the off-shoot of the structural adjustment program.Similarly,

massivereduction in publicsectorexpenditure during1990-2003is morea failureof the

stateto generate resourcesbecauseoftheparticular compositional specificsofthesociety

than an effectof the transitionof the economyunder the structuraladjustment.

Obviously,thereis a needto mountmoreinvestigative pursuits witha viewto understand

thegivenconstellation of thepowerbrokersin thecountry and theirimpacton thepoor,

throughthe choices they make. The influence,which the corruptionand related

governance problembearuponpoverty andinequality arenotexploredas yet.

Turnaround of theeconomyduringtherecentsub period(2003-2006) spurredby

domesticdemandescalationwhereinthegovernment patronised theautomobileindustry

ignoring theattendant costsofcongestion, environmental degradation and worstof all the

conspicuousconsumption as well as risingimportbill.The GDP growthof 6 percentper

annumhas beenregistered whichmayhave led to thedeclinein povertyand littlebitof

unemployment too, but income inequalities havenotonlypersisted butincreased.Inflow

of funds fromabroad due to geo-politicalfactorsand remittancesfacilitatedthe

government to expandpublicsectorspendingthereby havingpositiveeffecton poverty

situationsince2003.

Shorttermprospectsof thesustainability of theGDP growthare notbright.The

high inflation rate, widening current account deficits,sluggishexportperformance,

besidesfailureof theregimeto increasetax to GDP ratioand nationalsavingsare the

worrisomefactors.Studies conducted in the Growth Diagnostic Frameworkof

Haussemanidentify thelackof governance as majorconstraint to future growth[Qayyum

(2007)]. Studieswhichoptedneoclassicalgrowthaccountingtendto allude to the low

domesticsavinga majorbottleneck to futuregrowth[Din (2007)]. It mayalso be added

herethatTotal FactorProductivity (TFP) reflecting theefficiency of thegrowthprocess

appear to have declined over the decades.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 697

An intriguing factof thehistoryis thatPakistanwas successfulin reducingthe

poverty level during periodswhenthecountry

the receivedmassivefundsfromabroad

(1960s, 1980s and 2000-2006). It is also nota coincidencethatduringtheseperiodsthe

country was underthenondemocratic In otherwordswhatever

dispensation. thepoverty

alleviationoccurredwas not indigenousand hardlyenmeshedwiththe dynamicsof

growth,distribution and resourcemanagement issues a characteristicof self reliant

growth strategy. If one were to the

ignore highgrowth episodes of 1960s associated with

cold war,1980s an era of Afghanwarand since9/11waron terror, thenaturalgrowth

rateofPakistan'seconomyworksaroundto 3 to 4 percentperannumhardlykeepingup

pace withpopulationgrowth. Fundsfromabroadsupplemented thelow domesticsaving

and permitted high level of investment needed forhighergrowthrate.Also duringthese

highgrowthepisodes, PSDP as fraction of GDP rose to have a positiveinfluenceon

poverty situation.

III. POVERTY AND NATURAL RESOURCES INTERLINKAGES-

STUDY OF AGRO-CLIMATIC ZONES

In orderto discernsomewhatthe connectivity betweenpovertyreductionand

naturalresourcemanagement, poverty incidence and sourcesof incomeof thepoor by

agroclimatic zonesarediscussedin thissection.Pakistanbeingendowedwithdiversified

reliefexhibitsvaryingcroppingpattern dependingon wateravailability and typeof the

soil. Mountainousareas of NWFP, Balochistanand some partsof Punjab are generally

consideredas non-irrigated areas,wherecropslike wheatand maize are grown.In the

irrigatedareasin thenorthern Punjabgenerally basmatirice,wheatcombination is opted.

In SouthernPunjab and partsof Sindhcotton/wheat rotationis practiced.In southern

Sindh,exclusivelyIrririce is grown.Similarly,sugaris exclusivelygrownin some

irrigatedareaswherewateravailability permits.The extentto whichthespreadanddepth

of povertyvaries withthe different crops which embodydifferential mix of natural

resourcesis providedin theAppendixTable 8 whereinPunjaband Sindhprovincesare

dividedintoagroclimatic zones whereasBalochistanand NWFP are treatedas distinct

units.Povertyincidenceon thebasis of 2004-05HIES separately workedout forurban

and ruralareasin each zone are suggestive of an interesting resultthattheagriculturally

richzones like wheatcottonPunjaband Sindhappearto be poorerthantheremaining

areasintheseprovinces. Rankingson thebasisofpoverty incidenceputstheBarani(non-

irrigated)Punjab at the top registering only 7 percentof the populationbeing poor

whereasthoseresidingin wheat/cotton zones of Punjaband Sindhexhibited33 percent

and 23 percentpoverty.These findingsare similarto a previousstudyconductedby

Malik(2005) using2001-02data.

Urban-ruralpovertyincidence in different zones finds a close association

rendering homogeneity to zonal classification

in thePunjabprovincebutexhibitswide

disparitiesin Sindhwhereruralareasofa givenzone happento be muchpoorerthantheir

urbancounterparts.lt may be notedthatPakistaniagriculture reflectsa coexistenceof

peasantproprietorship in baraniand northernPunjab and feudalisticstructuretypifiedin

Southern Punjab and Sindh. The distribution

of land is skewed

substantially with overall

Gini coefficient being0.66. Accordingto Agricultural Census 2000 only aroundone-

thirds oftheruralhouseholdsownedlandwithmostofthem(61 percent)havinglandless

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

598 MuhammadIrfan

than5 acres. On the otherhand,two percentof the householdsat the top owned 30

percentof land.Andthislandinequality getstranslatedintoincomeinequality andhigher

levelof povertyamongthesharecroppers and tenantsamongthefarmpopulationin an

otherwise richagriculturalregionsof Punjaband Sindh.WhilstBalochistanand NWFP

accountfor 18 percentand BaraniPunjab accountsfor6 percentof totalpopulation,

nearlythree-fourth of thepopulationresidein areashavingirrigated In those

agriculture.

areas wherethefeudalisticstructure persistsaccounting forover 25 percent of therural

population failto getout of povertybecause themajor share of is

output appropriated by

landlordsas returnsto landareover50 percent.

Barani or non-irrigatedPunjab whichyieldedthe lowestlevels of povertyhas

benefited fromdiversedevelopments whichled thisarea to relativeprosperity. Priorto

independence the BritishEmpireprovidedmilitary and otherjobs disproportionately to

thisregion.This was the beginningof the road to relativeprosperity in theseareas

becausetheempirealso builthospitals, schoolsandinitiated otherdevelopment activities.

This low level of povertyof non-irrigated Punjab is also associatedwithlowerfamily

sizes and betterhumancapitalassets. Furthermore, becauseof thelocationof capitalof

country Islamabad, headquartersof all the threebranches of ArmedForces and hostof

otherindustrial the

activities, area is well developedthoughnot havingvast irrigated

lands.

Farm vs. Non-farmPopulation

Withinruralareas,thedistinctionbetweenfarmand nonfarm getsblurredbecause

factorand productmarketsare interlinked. In the ruralPakistannonfarmpopulation

appearsto be muchpoorerthanthefarmpopulation.While 36 percentof thenonfarm

populationaccordingto HIES 2004-05 is poor thecorresponding percentageforfarm

populationis 22. In urbansegmentsof thezones,however,theincidenceof povertyon

farmpopulationis higherthanon thenon-farm. The reasonsare obviousbecause in the

urban areas the non-farmpopulationis bettereducatedand skilled than the farm

population(see AppendixTable 9).

IV. SOURCES OF INCOME

Investigatingthedependenceof ruralas well as urbanpoor on different income

sourcesallude to theimportance of variousfactorsbearingupon thepovertyoutcome.

Accordingto theHouseholdIntegrated EconomicSurvey2004-05,wagesand salariesare

thesinglelargestsourcesof incomeaccounting for30 percentof thetotalincome.This is

followedby otheractivitieswhich presumablycompriseof enterpriseincome and

accountfor24 percentof thetotal.Cropand livestockproducttogether occupythethird

positionin thisrankingyielding20 percentof thetotalhouseholdincome.The shareof

livestockincomein totalincomeis muchless thanwhatis suggestedbyNationalIncome

Accounts,presumablythe latteris overestimated as suspectedby some researchers

8

[Malik (2005)]. Nearly percent of household income is accountedby domesticand

foreignremittances.Sources of incomedifferacrossrural/urban divide,by agroclimatic

zonesandby landsize classifications.For instance,wageincomeis 23 percentof totalin

ruralareas as comparedto 38 percentin urbanareas. Similarly,crop and livestock

incomeaccountsfor32 percentof totalhouseholdincomein ruralareas in contrastit

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 699

worksoutto 3 percentin urbanareas.Remittances constituteof9 percentof totalincome

in ruralareasas comparedto 6 percentin urbanareas.Starkdifferences existin theshare

ofotherincomepresumably theenterpriseincomebeing31 percentin urbanareasand 17

percentinruralareas.

Sourcesof incomecontrolling foragroclimatic zones is indicativeof thefactthat

theleastpoorzone (BaraniPunjab)and NWFP derivesubstantial portionof theincome

fromdomesticand foreignremittances 12

being percent and 13 percentrespectively.In

contrast thedependenceof thesezones is theloweston cropand livestock(9 percentof

the total).Wages as a sourceof incomeare also above averagein thesezones (see

AppendixTable 10). Crop and livestockincomeaccountsfor31 percentor moreof the

householdincome in cottonwheatPunjab and Sindh,low intensity Punjab and in

Balochistan.Non-farm incomeaccountsfor20 percenthouseholdincomein nearlyall

theregionswithnationalaveragebeing26 percent.In termsof poor/non-poor dividethe

dependenceof pooron wage incomeis higherthanthenon-poor, particularlyin Barani

areas,cottonwheatPunjabandSindhas wellas inNWFP andBalochistan.

In termsof landsize classification theroleof wagesis largeramongthelandless

and graduallydeclinesas one moves up the land size (see AppendixTable 11). The

remittances accountfor12 percentf thehouseholdincomeforsmalllandholder(1-2.5

acres) therebythesedeclineto 5 percentforthe largesize landholders(25 acres and

above) Crop and livestockincomeacquiressignificance forall thecategoriesof 5 acre

and above whereit accountsforover40 percenton theaverageand over57 percentfor

thelargestland size (25 acres and above). Interestingly, the shareof the nonfarm (or

enterprise) income is the 33 for

highest percent landlessto be followedby smallholders

(1-2.5 acres)22 percent. Fortheremaining landholderstheenterprise incomeaccounts

forless than15 percentofthetotal.

Clearly,theroleof different sourcesin thehouseholdincomedepictthesurvival

strategy of the population in rural areas. Ex-village and off-farm labour market

participation a

representsresponse to lower level of cropand livestockincomeeitherdue

to paucityof thelandresourcesor landconcentration amongthefewhandsas is thecase

in SouthernPunjab and Sindh rural.Non-farm(or enterprise)emergesto be more

importantfor landless and small holders who supplementtheir income through

engagement mostlyin low productivityinformal sector.

V. ROLE OF AGRICULTURAL GROWTH

Notwithstanding thefactthatthecontributionof agriculture

to GDP is around20

thetotality

percent, of theimpactof thegrowthin agriculturesectoris immense.This is

becauseof itsbackwardandforward linkageseffect.

Eventoday,70 percentofPakistan's

exportsare based on agricultural

produce and nearlytwo-thirds of the populationis

or on

directly indirectlydependent agriculture. Large scale surfaceirrigationwas

undertaken in the 19thcentury and subsequentmajorprojectslike Tarbelaand Mangia

Dam werecompletedafterindependence. Sincethenthedevelopments takingplace in the

sectorprovideda strongfoundation

agriculture to thedevelopment of theeconomy.Real

GDP growthin agriculture was thehighestin 1960-70(4.8 percent).Thenagainduring

1980-2000,thegrowthwas rangingbetween4 to 4.4 percent.Since the year2000, it

declinedto 3.5 percent.During the more recentperiod of 1998 to 2004-05, the

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

700 Muhammad

Irfan

agriculturalgrowthin percapitatermsafteradjustingtheofficialpopulationgrowthrate

[WorldBank (2007)] was negative(-1 percent).This to a largeextentexplainstheweak

linkbetweenpovertylevelsand agricultural growth, becausethelatterwas notsufficient

as well as it has been erraticexhibitingyear-wise The sectordependsto a

fluctuation.

largeextenton the production of majorcropslike wheatand cotton.The latterbeing

producedin Southern Punjaband Sindhwherelanddistribution is highlyskewedthereby

one getsan anomalousfindings thatagriculturally richzones are associatedwithhighest

levelsofpoverty.

Agricultural growthduringtheperiodof GreenRevolution(1970 to 1980) was

mostlyinputbased (seeds, fertiliser and water). Since theearly1990s,thetotalfactor

in

productivity crop sub-sector appears to have remainedstagnantor declined.

Deterioration in waterand soil qualitysince 1990s is also reported.In orderto achieve

perceptible growthin thefarmsector,measuresare neededto addressthedecliningsoil

fertility manypartsof thecountry.

in Accordingto theWorldBank (2007) study,around

Rs 70 billionper yearor 6.8 percentof agricultural GDP is lostdue to soil degradation

attributable in wateruse. It is also imperative

to inefficiency to diversify and venture into

high value crops wherever appropriate. Research on high value crop such as oilseeds,

vegetables,fruitsand livestockis desperatelyneeded.It may be added thatlivestock

production will have a majorimpacton povertyalleviationbecause it is moreevenly

distributed thanthe crop income.Improvement in waterdeliveryhas to be accorded

priority.

Efforts

madein thepastto redistribute thelandthrough landreforms almostfailed.

Now theland reforms have been officiallybanished.Negativeimplications of insecure

for

tenancyarrangement production can be addressed but politicalfeasibilityis not

certain,thoughproductivity gains accordingto some studiesare of the orderof 18

percentifsmallfarm sharecropper resultsfroma shiftto rentfixedtenancy.Efficiency of

land marketsand securityof tenancycan be improvedthroughimprovement of land

of sale andpurchaseoflandin an overallcontextof limitedarable

recordsandfacilitation

land.

Rural Non-farmEconomy

Preciseestimateof thenumberof ruralnon-farm enterprisehaveneverbeenmade

though a recentWorld Bank studyputs it around3.8 million.

Almost two-fifths of the

ruralpopulationis engagedas self-employed or wage earnerin thenon-farm enterprise

sector.Whilemostof theself-employed in tradesector,wageemployment is foundin the

construction

andtransport sectors.Around30 percentoftheaveragehouseholdincomein

ruralareasoriginatesin thissub-sector.

Mostoftheseenterprises in ruralareas,in nearby

small towns, are familybased. These enterprisessimply are reflectiveof low

and less skillednatureof thebusiness.These so called informal

productivity activitiesto

a largeextentare recyclingwages.Accordingto WorldBank studymedianvalue added

per workerwas Rs 18,000 in ruralareas and Rs 27,000 small townenterprises. Poor

and lack of access to credithas been identified

infrastructure as major constraint to

growth.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 70 1

VI. SUMMARY AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

The foregoing reviewis suggestiveof thefactthatdespitesome progressmade

the

during very recent period,poverty levelstendedto increasesince 1987-88and nearly

30 percentofthepopulationis belowthepoverty line.Povertyis mostlyconfinedto rural

areas whereinnon-farm populationemergesto be poorerthanthe farmpopulation.

Withinurbanareasthemajorcitiesare betterplaced withmuchless povertyincidence

thantheothersmallerurbancities.In factthelatterare closerto theruralareas in this

comparison.

Wages and salariescontribute themajorsourceof incometo be followedby the

non-farm enterprise income.Cropandlivestockoccupythethirdpositionthoughitvaries

bydifferent zonesandby socioeconomicgroupof thepopulation. Poor tendto relymore

on wage incomethanon othersources.A closer scrutinyof the spread of poverty

incidenceacross variousagro-climatic zones is suggestiveof the top positionbeing

occupiedby the least endowed zone of non-irrigated(Barani)Punjab,whilethe worst

conditions emergefortheagriculturally richzones of Wheat-Cotton producingzones of

Southern PunjabandSindh.Theseanomalousfindings can be explainedin termsof other

developmentalactivitiesfor Barani Punjab as well as major urban areas wherein

industrialandcommercial strideshavebeenmadein thepastas wellas present.Skewed

landdistribution whereinthemajority of incomeis appropriated bylandlordsreflectsthe

worstpoverty situation in therichagricultural zonesof southern PunjabandSindh.

Agricultural growth overtheyearshas beenresponsible forreducingpovertyboth

directlyas well as indirectly through development in other branches of the economy.

Agriculture sector a

experienced respectablegrowth rate during the greenrevolution

whichwas mostlyinputbased.Duringthelastdecadeor so theagriculture sectorsuffered

fromyear- wise erraticfluctuations due to droughts as well as emergenceof theproblem

ofsoil fertilitygenerally attributed to inefficiencyin theuse ofwater.

Thereis a needto reiterate thatPakistanis stilla naturalresourcebased economy.

The agriculture sectoris a primary employer and mostimportant contributor

to economic

surplus and the principalsourceof itsforeignexchange.Millionsof families,especially

thosethatarepoorand landless,dependon livestockformuchof theirfoodand income.

Agriculture contributed around67 percentof Pakistan'sforeignexchangeearnings -

mostof whichwas associatedwiththesale ofcottontextilesthoughagriculture's shareof

GDP hasdeclinedto 21 percent butitstillaccountsfor43.4 percentoftotalemployment,

while65.9 percentofthepopulation is dependent on agricultural production.

Although less than5 percentofPakistanhas forestcover,forests playa numberof

important roles,regulating the flow of waterthroughthe Indus River System(1RS),

reducingerosionand thebuild-upof sedimentbehinddam. Forestprovidesa sourceof

wood for construction, cookingand a wide rangeof otherproductsand createsan

important habitat for rare andendangered floraandfauna,providing medicinalplantsand

important grazing areas for livestock. Rangelandswhichcoveran estimated37.5 percent

of Pakistan'sland area will grow increasingly important over time as the country

attempts to developnew areasto producefoodand createotherproductsforitsgrowing

population.

It is imperative to emphasisethatseriousenvironmental damagesand stresseson

naturalresourcehave been experienced.A 1997 World Bank studyestimatedthat

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

702 MuhammadIrfan

environmental damageannuallycostsPakistantheequivalentof US$ 1.8 billion,owing

to higherhealthexpenditures, reducedlabourproductivity, and a wide rangeof other

and

explicit implicit costs.Pakistan's natural resource sector is underintensestress.The

forestsectoris severelydamaged,fisheries need majorremediation, agriculturalland is

increasingly becomingwater-logged, salineand fragmented whilegroundwater supplies

in places like Balochistanare runningout. The glaciersin the northern mountainsof

Pakistanare beginning to meltdue to globalwarmingand agriculture will eithergreatly

diminish orrequiremajoradjustments.

Population growthand poor managementhave reduced per capita water

availabilityfrom53,000 cubic metersto 1,200cubicmeters.Logginghas contributed to

the world'ssecond highestdeforestation rateand extensivesoil erosion.Each day the

IndusRiveradds an estimated 500 thousandtonsof sediment to theTarbelaDam, which

has reduceditslifespanby 22 percentand its waterholdingcapacityby 16 percent.The

irrigationsystemcontributesmillionsof tons of salt to the surrounding farmland.

Approximately 6.8 millionhectaresor aroundone-thirds of croppedarea in Pakistanare

impactedby salinity.The irrigation systemalso has wreckedhavocon thedeltaregion's

ecologicalbalance.An examination ofthechangesinthecroppingpattern consistentwith

water availabilityappears overdue. Possibilitiesof substituting drip/sprinklingthe

currentlyflood irrigationsystem has to be assessed.It is in this contextthe suggestion

thatuser chargesmay be crop specificto reflectwaterscarcitymeritsconsideration.

There is a desperateneed to change the water use practicesgiven the political

ofconstruction

infeasibility of largedams,albeitwithlimitedlifespan.

Very littleif any has beendiscussedaboutthenexusbetweenthenaturalresource

management and povertyreductionexceptthe mappingof povertywithagroclimatic

zones. Because of the emphasisupon monitoring the MDGs whereinthe focus of

researchers as well as data gathering exercisehas beenon estimating thepoverty. Below

fewsuggestions aremadeto initiatesomeexerciseto unravelthisnexusinPakistan.

(1) It is well-knownthatpoor rely much on naturalresourcesparticularly

underthe community ownershipsuch as forests,sea and riverwater.The

extentto whichtheseare misusedand exploitedneeds to be investigated

withparticularreferenceto propertyrightskeepingin view the survival

strategyof thepoor.

(2) Withinagricultureinefficient use of water is noticed with the ensuing

and worsening

salinity/sodicity soil conditions. to examinethe

It is imperative

extentto whichpoverty is thecause oreffectofthesedevelopments.

(3) Differentialaccess to irrigationwateris widespread.How muchpoorare at a

disadvantageous position needs to be documented.

(4) Relationbetweenemigration and thereturn flowof remittances and theland

use patternneeds to be reckonedparticularly in NWFP and otherhigh

emigration areas.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 703

APPENDIX

AppendixTable 1

ComparisonofPoverty Based on theOfficialPoverty

Estimates, Line,

1998-99,2000-01and 2004-05

1998-99 2000-01 2004-05 Difference

( 1)-(3) Difference(2)-(3)

Region Щ £} Q) (£ (3}

Urban 20.9 22.69 14.94 5.96 7.15

Rural 34.6 39.26 28.13 6.47 11.13

Overall 306 3446 23JH 6M 1052

Source: Haque andArif(2007).

AppendixTable 2

PovertyEstimatesin Pakistan,1998-99, 2001-02 and 2004-05

1998-99 2001-02 2004-05

Poverty National 30.0 34.4 29.2

Headcount Urban 21.0 22.8 19.1

Rate Rural 33.8 39.1 34.0

National 6.3 7.0 6.1

PovertyGap Urban 4.3 4.6 3.9

Rural 7.1 8.0 7.2

Squared Nation 2.0 2.1 2.0

PovertyGap Urban 1.3 1.4 1.2

Rural 2J. 2Л 23

Source: WorldBank(2007).

AppendixTable 3

Trendsin Poverty

Incidence

(PercentageofPopulationLivingBelowthePovertyLine)

1987-88 1996-97 1998-99 2001-02 2004-05

Pakistan 23 28 30 33 30

(2.4%) (3.6%) (3.3%) (-3.0%)

Urban 19 25 25 30 28

(3.5%) (0%) (6.7%) (-2.2%)

Rural 26 30 32 35 31

(1.7%) (3.3 %) (3.1 %) (-3.8 %)

Source: Jamal(2007).

Note: AGR frompreviousperiodaregivenin parenthesis.

AppendixTable 4

IncidenceofPoverty

byRural/Urban

Overall ___ RuralAreas

1998-99 2000-01 2004-05 1998-99 2000-01 2004-05 1998-99 2000-01 2004-05

WorldBank (2006d)

Punjab 29.8 30.7 29.5 23.7 23.0 21.2 32.2 33.8 33.4

Sindh 26.2 37.5 22.4 15.3 207 13.8 34.5 48.3 28.9

NWFP 408 42.3 39.3 26.1 30.0 26.1 43.3 44.4 41.9

Balochistan 22.1 37.2 32.9 25.2 27.4 21.5 21.6 39.3 35.8

Anwar(2006)

Punjab 31.6 32.2 29.7 24.2 23.2 206 34.6 35.8 33.9

Sindh 26.0 35.3 22.4 15.6 20.1 14.3 34.0 45.0 28.4

NWFP 41.3 41.3 38.9 27.1 29.0 26.5 43.7 43.4 41.4

Balochistan 21.6 35.5 33.1 22.9 26.2. 22.4 21.3 37.5 35.9

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

704 MuhammadIrfan

AppendixTable 5

PovertyIncidencebyProvinceand Region2004-05(Poor %)

Urban Areas Rural Areas Overall

Total MajorUrbanCentres Other Total Farm Non-farm Total

Pakistan 14.9 9.7 22.1 28.1 23.1 34.2 23.9

Punjab 16.3 11.8 21.0 28.0 19.8 36.6 24.3

Sindh 11.0 6.2 24.6 23.7 24.0 23.2 18.3

NWFP 21.9 20.7 22.5 34.1 32.0 37.0 32.1

Balochistan 18.5 74 25.6 28.8 223 36.5 26.7

Source: Based on HouseholdData Tabulation,HIES 2004-05.

AppendixTable 6

byRegionsand Overall-I 992-93to 2001-02

GiniCoefficient

Year FBS (2001) WorldBank(2002) Anwar(2005)

Overall

1992-93 0.2680 0.276 0.3937

1993-94 0.2709 0.276 0.3864

1998-99 0.3019 0.296 0.4187

2001-02 - - 0.4129

Rural Areas

1992-93 0.2389 0.252 0.3668

1993-94 0.2345 0.246 0.3647

1998-99 0.2521 0.251 0.3796

2001-02 - - 0.3762

UrbanAreas

1992-93 0.3170 0.316 0.3970

1993-94 0.3070 0.302 0.3685

1998-99 0.3596 0.353 0.4510

2001-02 - - 0.4615

AppendixTable 7

forPakistanbyRegionsbetween

ofPoverty

Decomposition

2001-02to2004-05and 1998-99to2001-02

Growth Redistribution Residual TotalChangein Poverty

1998-99to 2001-02

Pakistan 5.66 -2.05 -0.22 3.83

Urban 4.58 -1.82 0.99 1.77

Rural 6.12 -2.23 -0.7 4.59

2001-02to 2004-05

Pakistan -12.48 1.42 -0.5 10.56

Urban -8.06 1.18 0.91 7.79

Rural -14.29 2.2 -0.93 11.16

1998-99to 2004-05

Pakistan -5.90 -0.18 0.61 6.69

Urban -4.54 -1.42 0.02 5.98

Rural (Ш 094 6M

-6£7

Source:Anwar(2006).

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 705

AppendixTable 8

HeadcountbyAgroclimatic

Poverty Zone2004-05

(%)

Urban Rural Pakistan

Rice WheatPunjab 11.00 20.39 16.09

MixedPunjab 21.25 29.60 26.90

Cotton-WheatPunjab 20.27 36.54 33.02

Low Intensity

Punjab 34.94 29.47 30.34

BaraniPunjab 7.66 7.20 7.38

CottonWheatSindh 18.29 24.36 22.51

Rice- OtherSindh 8.43 23.09 15.82

NWFP 21.88 34.13 32.11

Balochistan 18.46 28.76 26.65

Total 1A94 28ЛЗ 23.94

Source:Based on HouseholdLevel Data Tabulation.

AppendixTable 9

Estimation byFarmvs.Non-farm

ofPoverty HouseholdbyAgro-climatic

Zone

Urban Rural Pakistan

Farm Non-farm Farm Non-farm Farm Non-farm

Rice-Wheat Punjab 4.20 11.33 11.10 28.54 16.09 83.91

MixedPunjab 8.66 22.32 21.03 37.06 26.90 73.10

Cotton-Wheat Punjab 4.56 22.25 29.17 44.00 33.02 66.98

Low IntensityPunjab 41.51 33.39 21.08 45.11 30.34 69.66

BaraniPunjab - 8.21 2.04 14.55 7.38 92.62

CottonwheatSind 27.80 17.47 24.12 24.65 22.51 77.49

Rice-OtherSind 18.45 8.07 23.85 21.83 15.82 84.18

NWFP 15.55 22.64 32.01 36.97 32.11 67.89

Balochistan 25.76 17.75 22.30 36.52 26.65 73.35

Total 14.90 85.10 28.10 78.90 23.94 76.06

Source:Based on HouseholdLevelTabulationofHIES 2004-05.

AppendixTable 10

SourcesofIncomebyPoverty

Status2004-05(Percentages)

Remittance Non

Wages/ Foreign+ Crop Livestock farm Rental Sale of Other Total

Salaries Pak Income Income Income Income PropertyIncome Income

Urban Extremely Poor 55.04 0.19 0.00 1.68 27.44 0.00 0.00 15.65 100.00

Ultra-poor 39.22 4.64 2.93 0.95 38.87 0.00 0.04 13.36 100.00

Poor 45.44 3.03 3.08 1.26 33.03 0.36 0.04 13.75 100.00

Quasi Non-poor 40.17 4.01 2.67 0.89 37.12 0.52 0.05 14.57 100.00

Non-poor 33.00 6.23 4.00 0.92 33.91 2.10 2.02 17.82 100.00

Total 37.07 5.08 3.46 0.97 34.77 1.34 1.12 16.19 100.00

Rural ExtremelyPoor 26.87 4.40 15.25 11.49 22.00 0.00 0.00 19.99 100.00

Ultra-poor 33.39 6.14 15.21 6.81 23.18 0.03 0.46 14.79 100.00

Poor 28.48 7.83 21.01 7.83 20.91 0.09 0.96 12.89 100.00

Quasi Non-poor 22.37 8.85 26.43 8.55 19.91 0.40 0.80 12.69 100.00

Nonpoor 15.30 11.58 32.22 6.97 16.80 0.79 1.58 14.77 100.00

Total 23.07 9.08 25.58 7.84 19.59 0.38 1.04 13.44 100.00

Pakistan ExtremelyPoor 31.14 3.76 12.94 10.00 22.83 0.00 0.00 19.33 100.00

Ultra-poor 34.95 5.74 11.92 5.24 27.38 0.02 0.35 14.41 100.00

Poor 32.94 6.57 16.30 6.10 24.10 0.16 0.72 13.11 100.00

Quasi Non-poor 28.99 7.05 17.59 5.70 26.31 0.44 0.52 13.39 100.00

Non-poor 26.19 8.29 14.85 3.24 27.33 1.59 1.85 16.65 100.00

Total 29.13 7.34 16.00 4.86 26.16 0.80 1.07 14.63 100.00

Source: Based on HouseholdLevel datatabulation.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

706 MuhammadIrfan

AppendixTable 11

SourcesofIncomebyLand Size - 2004-05 (Percentages)

Wages/ Crop Livestock Non-farmRental Sale of Other

Land Category Salaries RemittanceIncome Income Income Income propertyIncome Total

No land 37.11 7^21 1% 2Л6 33.23 Ш Õ79 15.53 100

1-2.5 28.42 12.26 17.52 6.62 22.13 0.27 0.19 12.59 100

2.5-5 21.71 8.34 28.24 8.23 14.98 0.34 3.87 14.28 100

5-7.5 13.86 8.31 34.97 8.82 18.08 0.10 0.17 15.69 100

7.5-12.5 16.17 9.48 35.84 9.29 15.36 0.24 1.34 12.29 100

12.5-25 17.21 9.25 32.91 9.97 14.16 0.43 2.82 13.26 100

25-hi 10.87 5.59 47.55 10.32 11.46 0.55 0.93 12.72 100

Total 29.13 7.34 16.00 4.86 26.16 0.80 1.07 14.63 100

Source: Based on HouseholdLevel HIES 2004-05Data Tabulation.

AppendixTable 12

Numberof Yearsto GetoutofPovertybyGrowthand EquityScenarios

Low Intermediate High

Poverty Growth Growth Growth

Equitable Poverty

Extreme 70 24 15

Moderate 29 10 6

HighlyInequitablePoverty

Extreme 139 47 29

Moderate 58 20 12

ModeratelyInequitablePoverty

Extreme 93 32 19

Moderate 39 13 8

Source:Weissand Khan(2006).

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and NaturalResourceManagement

Poverty 707

AppendixTable 13

ofZonesin TermsofDistricts

Distribution

AgroclimaticZones Districts

1. Rice/WheatPunjab Sialkot

Gujrat

Gujranwala

Sheikhupura

Lahore

Kasur

Narowal

Mandi Bahauddin

Hafízabad

2. Mixed Punjab Sargodha

Khushab

Jhang

Faisalabad

Toba Тек Singh

Okara

3. Cotton/WheatPunjab Sahiwal

Bahawalnagar

Bahawalpur

Rahim Yar Khan

Multan

Vehari

Lodhran

Khanewal

Pakpattan

4. Low IntensityPunjab D. G. Khan

Rajanpur

Muzaffargarh

Leiah

Mianwali

Bhakkar

5. Barani Punjab Atttock

Jhclum

Rawalpindi

Islamabad

Chakwal

6. Cotton/WheatSindh Sukkur

Khairpur

Nawabshah

Hyderabad

Thaiparker

Nousheroferoz

Ghotki

Umerkot

Mirpurkhas

Sangbar

7. Rice OtherSindh Jacobbabad

Larkana

Dadu

Thatta

Badin

Shikarpur

Karachi

8. NWFP Swat

Dir

Chitral

Buner

Charsada

Noshera

Peshawar

Kohat

Karak

Tank

Abbottabad

Haripur

Batagram

Kohistan

Mardan

Swabi

Bannu

Lakkimarwat

Shangla

Malakand Agency

Hangu

D.I. Khan

9. Balochistan Quetta Division

Sibi Division

Kalat Division

Makran Division

Zhob Division

Nasirabad Division (Excluding Nasirabad District)

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

708 MuhammadIrfan

REFERENCES

Anwar,Talat (2006) Poverty, Growthand Inequalityin Pakistan.Paperpresentedat the

23rdAnnualGeneralMeetingofPakistanSocietyof Development Economics,PIDE,

December2006.

Din, Musleh-ud(2007) An Analysisof Pakistan'sGrowthExperience1983-84-1987-88

and 2002-03 to 2005-06. PakistanPovertyAssessmentUpdate. (BackgroundPaper

Series- ADB Pakistan.)

Haque, NadeemUl and G. M. Arif(2007) Understanding Povertyand Social Outcomes

in Pakistan. A Study preparedfor DFID. Pakistan Instituteof Development

Economics,Islamabad.June.

Irfan,M. and R. Amjad (1984) Povertyin RuralPakistanIn A. R. Khan and Eddy Lee

(eds.) PovertyinRuralAsia. DLO,AsianEmployment Programme.

Jamal,Haroon(2007) UpdatingPovertyand InequalityEstimates:2005, PANAROMA:

Social PolicyandDevelopment Centre(SPDC), Karachi(Mimeographed.)

Malik,Sohail J.(2005) AgriculturalGrowthand RuralPoverty - A Reviewof Evidence.

AsianDevelopment Bank,PRM Islamabad.(Working PaperNo. 7.)

Qayyum, Abdul,et al (2007) GrowthDiagnosticsin Pakistan.(PIDE WorkingPaperNo.

47.)

Weiss, Johnand Haider A. Khan (2006) PovertyStrategiesin Asia: A GrowthPlus

Approach.A Jointpublication forADB Institute

andEdwardElgarPublishing.

World Bank (2006a) Pakistan'sGrowthand Competitiveness. Washington, DC. The

WorldBank.(ReportNo.3499- PK.)

WorldBank(2006b) Summary ofKeyFindingsand Recommendations. WorldBank.

World Bank (2007) Pakistan PromotingRural Growthand PovertyReduction -

SustainableDevelopment Unit.SouthAsia Region,WorldBank.

Zaidi,S. Akbar(2005) Issues inPakistan'sEconomy.Karachi:OxfordUniversity Press.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.182 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 22:18:46 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- 3rd Quarter Daily Lesson Log - Docx2Document23 pages3rd Quarter Daily Lesson Log - Docx2noeme100% (5)

- WP0 Box 341 University 0 Press 2006Document638 pagesWP0 Box 341 University 0 Press 2006Hira Farooqi100% (1)

- Meezan Bank ProjectDocument38 pagesMeezan Bank Projectnaqash1111100% (1)

- Water Accounting for Water Governance and Sustainable Development: White PaperFrom EverandWater Accounting for Water Governance and Sustainable Development: White PaperNo ratings yet

- Democracy in Pakistan Hopes and HurdlesDocument3 pagesDemocracy in Pakistan Hopes and HurdlesFaisal Shafique100% (4)

- Zimbabwe Food Systems ProfileDocument52 pagesZimbabwe Food Systems ProfileAnna BrazierNo ratings yet

- Comparing Sustainable Development Between India, Japan and Sudan: A Comparative StudyDocument33 pagesComparing Sustainable Development Between India, Japan and Sudan: A Comparative StudyaliishaanNo ratings yet

- Administrator,+a04 221 238Document18 pagesAdministrator,+a04 221 238Ansar AliNo ratings yet

- Economics CiaDocument5 pagesEconomics CiaKartik Mehta SEC-C 2021No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S187802961400070X MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S187802961400070X MainFajar NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Agriculture and Food Security PolicyDocument23 pagesAgriculture and Food Security PolicyKumar AkNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Poverty Reduction in PakistanDocument8 pagesResearch Papers On Poverty Reduction in Pakistanjtbowtgkf100% (1)

- Policy Draft 29 SeptemberDocument23 pagesPolicy Draft 29 SeptembershaziadurraniNo ratings yet

- Eco Proj - NiharikkaDocument9 pagesEco Proj - NiharikkaniharikkaNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Poverty Reduction in PakistanDocument7 pagesThesis On Poverty Reduction in Pakistanbsqbr7px100% (1)

- 6 Paper 715 CHEEMA VI ROLE OF MICROFINANCE IN POVERTY ALLEVIATION IN RURAL AREAS OF DISTRICT SARGODHA PAKISTAN 1Document18 pages6 Paper 715 CHEEMA VI ROLE OF MICROFINANCE IN POVERTY ALLEVIATION IN RURAL AREAS OF DISTRICT SARGODHA PAKISTAN 1Miss ZoobiNo ratings yet

- Geography: Test SeriesDocument9 pagesGeography: Test SeriesIhtisham Ul HaqNo ratings yet

- How Do Countries Specialize in Agricultural ProducDocument13 pagesHow Do Countries Specialize in Agricultural ProducFernando Hernández TaboadaNo ratings yet

- Mutinta Siamuyoba Module 2 AssignmentDocument4 pagesMutinta Siamuyoba Module 2 AssignmentMutinta MubitaNo ratings yet

- Article CRA PDFDocument8 pagesArticle CRA PDFNasreen BanuNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Poverty Reduction in PakistanDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Poverty Reduction in Pakistancagvznh1100% (1)

- Development Challenges in Paraguay: Alejandro QuijadaDocument7 pagesDevelopment Challenges in Paraguay: Alejandro QuijadaKasey PastorNo ratings yet

- Indian Economy Push and Pull Approach of GrowthDocument3 pagesIndian Economy Push and Pull Approach of GrowthEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Position PaperDocument8 pagesPosition Papermjdr040804No ratings yet

- Food Security Issues and Challenges: A Case Study of PotoharDocument24 pagesFood Security Issues and Challenges: A Case Study of PotoharFiaz HussainNo ratings yet

- AgritourismDocument9 pagesAgritourismaimeejoreenabad.hau.2No ratings yet

- 2021 09 15 en National Pathways For Food Systems Transformation in Pakistan Sep 15 2021Document6 pages2021 09 15 en National Pathways For Food Systems Transformation in Pakistan Sep 15 2021Majid khanNo ratings yet

- MAricultura Artigo Internacional 2021Document18 pagesMAricultura Artigo Internacional 2021paula.ritterNo ratings yet

- AgricultureDocument10 pagesAgricultureAnAn LeeNo ratings yet

- Options and Priorities For Agriculture in India On The Eve of The Twelfth Five-Year PlanDocument3 pagesOptions and Priorities For Agriculture in India On The Eve of The Twelfth Five-Year Plansrijit.mishra4192No ratings yet

- IJCRT2208435Document21 pagesIJCRT2208435Chris Jan CanonesNo ratings yet

- A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Building A Dam in Pakistan: To Mitigate Floods, Promote Tourism, Boost Agriculture, and Generate ElectricityDocument16 pagesA Cost-Benefit Analysis of Building A Dam in Pakistan: To Mitigate Floods, Promote Tourism, Boost Agriculture, and Generate ElectricityMamta AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 12 01638 v2Document18 pagesSustainability 12 01638 v2Samsul HudaNo ratings yet

- Cash Transfers and The Rice Economy of Bicol, Philippines 1: December 2018Document21 pagesCash Transfers and The Rice Economy of Bicol, Philippines 1: December 2018Abigail CachoNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Agriculture Dev For Food SecurityDocument131 pagesSustainable Agriculture Dev For Food SecurityFarhat Abbas DurraniNo ratings yet

- The Environment-Poverty Nexus in Evaluation ImplicDocument8 pagesThe Environment-Poverty Nexus in Evaluation Implichebisax558No ratings yet

- J World Aquaculture Soc - 2023 - Jolly - Dynamics of Aquaculture GovernanceDocument55 pagesJ World Aquaculture Soc - 2023 - Jolly - Dynamics of Aquaculture GovernanceDavies KamwandiNo ratings yet

- Energy Use, Poverty and Development in The SADC: J C NkomoDocument8 pagesEnergy Use, Poverty and Development in The SADC: J C NkomoJohn TauloNo ratings yet

- Microfinance Impact On Agricultural Production in Developing CountriesDocument19 pagesMicrofinance Impact On Agricultural Production in Developing CountriesRisman SudarmajiNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument27 pagesAssignmentRZ RashedNo ratings yet

- Establishing Rice CentreDocument16 pagesEstablishing Rice Centrepaschal makoyeNo ratings yet

- Climate Woes and PopulationDocument2 pagesClimate Woes and PopulationAsif Khan ShinwariNo ratings yet

- Pop Ed Kala Mo MajorDocument9 pagesPop Ed Kala Mo MajorRyan Carlo IbayanNo ratings yet

- Urban Agriculture: and Food SecurityDocument15 pagesUrban Agriculture: and Food SecurityViata VieNo ratings yet

- Sustainability Report On ITCDocument6 pagesSustainability Report On ITCPravendraSinghNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Impacts of International Agricultural Investments On The Economy of African Rural Populations A Concise ReviewDocument8 pagesEvaluation of The Impacts of International Agricultural Investments On The Economy of African Rural Populations A Concise ReviewEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Urbanization - A Problem To Food ProductionDocument13 pagesUrbanization - A Problem To Food ProductionAayush100% (1)

- Population and Sustainable DevelopmentDocument6 pagesPopulation and Sustainable DevelopmentMukuka KowaNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Growth in IndiaDocument40 pagesInclusive Growth in IndiaPhxx619No ratings yet

- Dynamic 2 2020 PDFDocument10 pagesDynamic 2 2020 PDFAdlu AbdilahNo ratings yet

- A Meal Plan For All of IndiaDocument5 pagesA Meal Plan For All of Indiasriniwaas chhari thNo ratings yet

- Aligning The Future of Fisheries and Aquaculture With The 2030 Agenda For Sustainable DevelopmentDocument21 pagesAligning The Future of Fisheries and Aquaculture With The 2030 Agenda For Sustainable DevelopmentEnrique MartinezNo ratings yet

- RRLDocument12 pagesRRLTrisha Joy PagunuranNo ratings yet

- 06 Ijmres 10022020Document11 pages06 Ijmres 10022020International Journal of Management Research and Emerging SciencesNo ratings yet

- Growth of Economic Food SystemsDocument12 pagesGrowth of Economic Food SystemsrandyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document22 pagesChapter 6melissagonzalezcaamalNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Food Security in NigeriaDocument8 pagesThesis On Food Security in Nigeriaannjohnsoncincinnati100% (2)

- Environmental Economics Term Paper FinalDocument13 pagesEnvironmental Economics Term Paper FinalAsfaw KelbessaNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument4 pagesEssaykristinemayobsidNo ratings yet

- Proposal - Performance Assessment and Improvement PDFDocument21 pagesProposal - Performance Assessment and Improvement PDFMekonen Ayana0% (1)

- Non Traditional Security Threats BilalDocument12 pagesNon Traditional Security Threats BilalAsif Khan ShinwariNo ratings yet

- Institutional Reforms and Agricultural Policy Process: Lessons From Democratic Republic of CongoDocument22 pagesInstitutional Reforms and Agricultural Policy Process: Lessons From Democratic Republic of CongoDawitNo ratings yet

- Battling Climate Change and Transforming Agri-Food Systems: Asia–Pacific Rural Development and Food Security Forum 2022 Highlights and TakeawaysFrom EverandBattling Climate Change and Transforming Agri-Food Systems: Asia–Pacific Rural Development and Food Security Forum 2022 Highlights and TakeawaysNo ratings yet

- Ahmed Saleem Khan Assignment 1 STATADocument3 pagesAhmed Saleem Khan Assignment 1 STATAMahnoorNo ratings yet

- Research Methods Course Outline 2021Document7 pagesResearch Methods Course Outline 2021MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Quiz 1Document4 pagesQuiz 1MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Econometrics II, Winter 2020, Quiz 1 - Version A, SolutionDocument4 pagesEconometrics II, Winter 2020, Quiz 1 - Version A, SolutionMahnoorNo ratings yet

- Munch & Luv - Will Opa! Become The Fry Everyone Loves?: May 20, 2021. Time: 1:45 Hours. Marks: 50Document2 pagesMunch & Luv - Will Opa! Become The Fry Everyone Loves?: May 20, 2021. Time: 1:45 Hours. Marks: 50MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Shezan International Annual Report 2017Document64 pagesShezan International Annual Report 2017MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Lahore School of EconomicsDocument10 pagesLahore School of EconomicsMahnoorNo ratings yet

- Name: Financial Statement Analysis Mid Term Spring 2021 Bba Iii/ Sec A 1. Below Are The Balance Sheet and Income Statement For Anderson CorporationDocument2 pagesName: Financial Statement Analysis Mid Term Spring 2021 Bba Iii/ Sec A 1. Below Are The Balance Sheet and Income Statement For Anderson CorporationMahnoorNo ratings yet

- Lahore School of Economics Financial Statement Analysis Assignment 1Document1 pageLahore School of Economics Financial Statement Analysis Assignment 1MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Q: 1.3, 1.4, and 1.5: Lahore School of Economics Assignment 3 Financial Statement AnalysisDocument1 pageChapter 1 Q: 1.3, 1.4, and 1.5: Lahore School of Economics Assignment 3 Financial Statement AnalysisMahnoorNo ratings yet

- Macro Quiz 1Document3 pagesMacro Quiz 1MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Growth 1Document57 pagesGrowth 1MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Growth 2Document52 pagesGrowth 2MahnoorNo ratings yet

- Chapter Thirteen: Retailing and WholesalingDocument40 pagesChapter Thirteen: Retailing and WholesalingMahnoorNo ratings yet

- List of Banks EtcDocument3 pagesList of Banks EtcMehmood Ul HassanNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs Css McqsDocument11 pagesCurrent Affairs Css McqsMuhammadMaoozNo ratings yet

- Presidential or Parliamentary System in PakistanDocument5 pagesPresidential or Parliamentary System in PakistanKhalid Latif KhanNo ratings yet

- End-Term Examinations Spring Semester 22'Document6 pagesEnd-Term Examinations Spring Semester 22'dhriti ssomasundarNo ratings yet

- FPSC@FPSC - Gov.pk: - Second Class or Grade C' Master's Degree From A University Recognized by The HECDocument7 pagesFPSC@FPSC - Gov.pk: - Second Class or Grade C' Master's Degree From A University Recognized by The HECEngr Iftikhar ChandioNo ratings yet

- Enlisted Political Parties With ECP 5-10-22Document11 pagesEnlisted Political Parties With ECP 5-10-22Copy PaistNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Affairs Past McqsDocument45 pagesPakistan Affairs Past McqsMoazimAli100% (2)

- Government of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentDocument3 pagesGovernment of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentYasir GhafoorNo ratings yet

- Cash Conversion Cycle and ProfitabilityDocument42 pagesCash Conversion Cycle and ProfitabilityasmiNo ratings yet

- Overpopulation ITS CAUSES AND EFFECTSDocument7 pagesOverpopulation ITS CAUSES AND EFFECTSAsif Khan ShinwariNo ratings yet

- Bibliography & Glossary: A: Archival Sources B: Other Primary Sources C: Secondary SourcesDocument31 pagesBibliography & Glossary: A: Archival Sources B: Other Primary Sources C: Secondary SourcesNawaz SafiNo ratings yet

- Instructions Visits AbroadDocument4 pagesInstructions Visits AbroadMuhammad AliNo ratings yet

- NIDB BrochureDocument158 pagesNIDB BrochureRoshinNo ratings yet

- Lec 27-28 International TradeDocument20 pagesLec 27-28 International TradeJutt TheMagicianNo ratings yet

- Key Success Factors (KSF)Document8 pagesKey Success Factors (KSF)muhammad zeeshanNo ratings yet

- PIO For DistrictsDocument4 pagesPIO For DistrictsMuhammad Noman HaiderNo ratings yet

- Interview Prog No.1-2022 Updated-24!01!2022Document6 pagesInterview Prog No.1-2022 Updated-24!01!2022arsalanssgNo ratings yet

- Guest List of Karachi For NYHL SeminarDocument2 pagesGuest List of Karachi For NYHL SeminarMuhammad MujtabaNo ratings yet

- Pak301 Final Term Solved McqsDocument6 pagesPak301 Final Term Solved McqsAwais SharifNo ratings yet

- HCP Ba Unit 1.1Document19 pagesHCP Ba Unit 1.1jot sandhuNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Role SAARCDocument4 pagesPakistan Role SAARCMir HassanNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs PapersDocument17 pagesCurrent Affairs PapershoodwinkNo ratings yet

- Project On Ibrahim Fibers LTDDocument53 pagesProject On Ibrahim Fibers LTDumarfaro100% (1)

- Summary of Quaid e Azam SpeechDocument1 pageSummary of Quaid e Azam SpeechAbdullah KhanNo ratings yet

- Rashan Distribution ListDocument35 pagesRashan Distribution ListYasser KhalidNo ratings yet

- Pending Status As of 20-April-2017Document570 pagesPending Status As of 20-April-2017Shavi SpeakingNo ratings yet

- Six Point MovementDocument22 pagesSix Point MovementSayed Jaber Chowdhury100% (1)