Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Systematic Review of Adherence With Medication For Diabetes

Uploaded by

rizkaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Systematic Review of Adherence With Medication For Diabetes

Uploaded by

rizkaCopyright:

Available Formats

Reviews/Commentaries/Position Statements

R E V I E W A R T I C L E

A Systematic Review of Adherence With

Medications for Diabetes

JOYCE A. CRAMER als with chronic diseases. Problems with

poor self-management of drug therapy

may exacerbate the burden of diabetes.

Several studies suggest that a large

proportion of people with diabetes have

OBJECTIVE — The purpose of this study was to determine the extent to which patients omit difficulty managing their medication reg-

doses of medications prescribed for diabetes. imens (oral hypoglycemic agents [OHAs]

and insulin) as well as other aspects of

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS — A literature search (1966 –2003) was per- self-management (1,5,6). Whereas some

formed to identify reports with quantitative data on adherence with oral hypoglycemic agents

(OHAs) and insulin and correlations between adherence rates and glycemic control. Adequate

studies that have assessed adherence

documentation of adherence was found in 15 retrospective studies of OHA prescription refill among young people with type 1 diabetes

rates, 5 prospective electronic monitoring OHA studies, and 3 retrospective insulin studies. (6,7), little is known about adherence to

insulin regimens in patients with type 2

RESULTS — Retrospective analyses showed that adherence to OHA therapy ranged from 36 diabetes.

to 93% in patients remaining on treatment for 6 –24 months. Prospective electronic monitoring This systematic review was under-

studies documented that patients took 67– 85% of OHA doses as prescribed. Electronic moni- taken 1) to assess the extent of poor ad-

toring identified poor compliers for interventions that improved adherence (61–79%; P ⬍ 0.05). herence and persistence with OHAs and

Young patients filled prescriptions for one-third of prescribed insulin doses. Insulin adherence insulin and 2) to link adherence rates with

among patients with type 2 diabetes was 62– 64%. glycemic control.

CONCLUSIONS — This review confirms that many patients for whom diabetes medication

was prescribed were poor compliers with treatment, including both OHAs and insulin. However, RESEARCH DESIGN AND

electronic monitoring systems were useful in improving adherence for individual patients. Sim- METHODS

ilar electronic monitoring systems for insulin administration could help healthcare providers

determine patients needing additional support. Literature search

A systematic literature search was con-

Diabetes Care 27:1218 –1224, 2004 ducted to identify articles containing in-

formation on the rate of adherence or

persistence with OHAs or insulin. Ab-

stracts captured by the systematic litera-

D

iabetes is a complex disorder that tence), compliance is the default medical

requires constant attention to diet, term used in the literature (MEDLINE) to ture search of MEDLINE (1966 to April

exercise, glucose monitoring, and describe medication dosing (2). However, 2003), Current Contents (1993 to April

medication to achieve good glycemic con- the World Health Organization has pro- 2003), Health & Psychosocial Instru-

trol. Glasgow (1) conceptualized the com- moted the term “adherence” for use in ments (1985–2003), and Cochrane Col-

plexity of diabetes regimens, creating a chronic disorders as “the extent to which laborative databases were first screened

model linking disease management and a person’s behavior—taking medication, against the protocol inclusion criteria.

health outcomes with interactions be- following diet, and/or executing lifestyle The Level 1 screen identified papers re-

tween patients and their healthcare pro- changes— corresponds with agreed rec- lated to the main topic of interest. Ab-

viders. Factors contributing to optimum ommendations from a health care pro- stracts passing the Level 1 screen were

disease management included age, com- vider” (3). then retrieved for screening against the

plexity of treatment, duration of disease, The incidence of type 2 diabetes is inclusion criteria (Level 2 screen). Full ar-

depression, and psychosocial issues (1). rapidly increasing, largely in older, over- ticles meeting the inclusion criteria were

Although a variety of terms have been weight patients who have concomitant reviewed in detail (Level 3 screen).

used to describe these self-management cardiovascular risks (4). However, health

or self-care activities (e.g., adherence, care systems often do not have adequate Inclusion criteria

compliance, concordance, fidelity, persis- resources to provide support to individu- Papers were included in this review if 1) a

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● dosing regimen was evaluated and medi-

From the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

cation adherence or persistence rates

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Joyce A. Cramer, Yale University School of Medicine, 950 were reported and 2) study design and

Campbell Ave. (Room 7-127, G7E), West Haven, CT 06516-2770. E-mail: joyce.cramer@yale.edu. methods for calculation of adherence

Received for publication 18 August 2003 and accepted in revised form 18 January 2004. were described. The papers must have in-

J.C. is a member of an advisory panel of Novo Nordisk and has received honoraria or consulting fees from cluded details of the methods used to de-

Novo Nordisk.

Abbreviations: MEMS, Medication Event Monitor Systems; MUSE-P, Medication Usage Skills for Effec- termine adherence with a hypoglycemic

tiveness Program; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent. agent (e.g., self-report, physician/nurse

© 2004 by the American Diabetes Association. estimate, tablet count, prescription refill,

1218 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 27, NUMBER 5, MAY 2004

Cramer

electronic monitoring) and some numeric endpoints (e.g., 90%), below which pa- Analyses. Descriptive statistics (means,

results. Categorical results were consid- tients were considered “noncompliant” ranges) present data from the selected re-

ered a lower level of information than with the regimen. Adherence with “dose ports tabulated by methodology (retro-

data. The most desirable reports included intervals” was defined as the proportion spective database review, prospective

both adherence rates and HbA1c levels. of doses taken within the appropriate monitoring), and class of medication

Reports of interventions that did not in- window (e.g., 24 ⫹ 12 h for once-daily (OHA, insulin).

clude adherence rates were excluded. Re- regimens, 12 ⫹ 6 h for twice-daily regi-

ports of adherence with diet or exercise mens). RESULTS — The systematic review

that did not also include medication ad- Treatment “persistence” was defined was based on 20 reports that included

herence rates were also excluded. Reports as either the proportion of patients who quantitative information on adherence or

may be retrospective surveys, prospective remained on treatment for a specified pe- persistence with diabetes medications

clinical trials, or prospective studies of ad- riod (e.g., 12 months) or the mean num- (11–30). The few studies that included

herence interventions. Methods may be ber of days to treatment discontinuation. laboratory data all showed HbA1c levels

database analyses of populations or elec- Retrospective database assessment. ⬎7%.

tronic monitoring of individual patients. Prescription benefit organizations (PBOs)

that manage prescriptions and health OHA: retrospective analyses

Search strategy maintenance organizations (HMOs) that Adherence rates among 11 retrospective

Key words for the database search were “pa- manage the overall healthcare of patients studies (19 cohorts) (11,14 –16,18 –

tient adherence” and “patient compliance” have databases containing information 22,24,25) using large databases ranged

cross-linked with “diabetes mellitus,” “hy- about use of prescription medications. from 36 to 93% (excluding the study with

poglycemic agents,” and “insulin.” The term Records of new prescriptions and refills categorical adherence rates) (17) (Table

“adherence” was linked automatically to the can be tabulated using unique patient 1). The mean age of patients in all these

term “compliance” in MEDLINE as the pre- identifiers. Some databases also are linked studies was ⬎50 years, indicating that

ferred term. Within the terms, sub-items to diagnostic codes as well as laboratory these were older patients with type 2 dia-

were selected as: Administration & Dosage, and medical visit data that describe health betes. The open observational (noncom-

Adverse Effects, Therapeutic Use, Preven- service utilization for a cohort. Searches parative) studies (11,20,22,24,25) had

tion & Control, Drug Therapy, Psychology, similar results, ranging from 79 to 85%

can be made to ascertain the types of med-

Statistics & Numerical Data, and Econom- adherence with OHAs during 6 –36

ications, prescribed dose and regimen,

ics, as available for each term. The databases months of observation. Several studies

and number of times the patient obtained

identified 186,188 publications. compared cohorts with different regi-

a refill. These population-based surveys

Level 1 searches combining terms mens. Depressed patients had lower ad-

provide an overview of drug utilization

identified 242 publications that appeared herence rates than nondepressed patients

during a period of time.

to relate to the topic of interest. (85 vs. 93%) (14). Once-daily regimens

Level 2 was a review of abstracts from Prospective monitoring. Electronic had higher adherence than twice-daily

the reports identified in Level 1, using the monitoring technology collects events regimens (61 vs. 52%) (16). Mono-

inclusion criteria. This stage identified 38 based on taking medication from a mon- therapy regimens had higher adherence

reports as potentially having relevant itored container, stores events, and lists than polytherapy regimens (49 vs. 36%)

data. medication dosing for an individual. (14) or a higher proportion of patients

Level 3 was a review of the papers Medication Event Monitor Systems achieving high adherence rates (35 vs.

identified in Level 2. These citations were (MEMS; APREX, Division of AARDEX, 27% at 90% or higher adherence rates)

supplemented with selected references Union City, CA) were used in some pro- (17). Patients converting from mono-

from articles. This stage identified 19 pa- spective studies. MEMS are standard therapy or polytherapy to a single combi-

pers and one abstract (with additional in- medication container bottle caps with a nation tablet improved their adherence

formation from the authors) that met the microprocessor that records every bottle rates by 23 and 16%, respectively (19).

inclusion criteria. opening. Patients are given bottles with a The only report with adherence rates

The systematic search resulted in 20 MEMS cap and instructions to take all ⬍50% was a survey of California Medic-

publications with adequate data on mea- doses of the oral medication from that aid (MediCal) patients newly treated with

surement of adherence with an OHA or bottle. Data are downloaded for display as OHAs (15). Other studies included pa-

insulin. a calendar of events (8). Electronic mon- tients with chronic treatment.

itoring provides information about medi- Seven reports (nine cohorts) of OHA

Adherence assessment cation usage at the level of the individual treatment persistence ranged from 16 to

Definitions. For this review, medication patient. Some researchers do not inform 80% in patients remaining on treatment

adherence was operationalized as “taking patients that they are being monitored to for 6 –24 months. Four studies reported

medication as prescribed and/or agreed avoid an effect of observation (Hawthorne 83–300 days to discontinuation (Table

between the patients and the health care effect). Cramer (9,10) developed a 1). The methodology differed among

provider.” No studies provided informa- method, the Medication Usage Skills for studies, so that cross-overs to an alterna-

tion about the level of the patient’s agree- Effectiveness Program (MUSE-P), that tive OHA or insulin might not have been

ment with the regimen. The “adherence uses electronic monitoring data displayed counted as discontinuation. Two reports

rate” was the proportion of doses taken as on a computer screen as a teaching tool to with large proportions (58 and 70%) of

prescribed. Some reports used categorical enhance medication adherence. patients remaining on treatment for

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 27, NUMBER 5, MAY 2004 1219

1220

Medication adherence

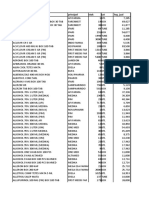

Table 1—Retrospective database studies of OHA for type 2 diabetic patients

Follow-up Age Adherence Persistance Persistance

Reference Population Medications (months) HbA1c (years) n rate (percent) (days)

Boccuzzi et al. (11) PBO, new start OHA monotherapy 12 — 60 ⫾ 14 79,498 79% 58%* 83 ⫾ 71

Brown et al. (12) HMO, new start OHA ⫹ Insulin (10 years) — — 693 all — 70%† —

Catalan et al. (13) Canada Acarbose 12 — 51 ⫾ 9 216 young 16%* 83

— 72 ⫾ 5 677 elderly 20%* 105

Chlechanowski et al. (14) HMO, all OHA ⫹ Insulin 12 7.4 ⫾ 1.4 64 ⫾ 11 119 not depressed 93% — —

8.0 ⫾ 1.5 121 depressed 85% — —

Dailey et al. (15) Medicaid, new Monotherapy 18 — — 37,431 49% 36%* —

start

Polytherapy 36% 22%* —

Dezii and Kawabata (16) PBO Glipizide, o.d. 12 — 55 ⫾ 13 992 61% 44%* —

Glipizide, b.i.d. 52% 36%* —

Donnan et al. (17) Scotland Monotherapy 12 — 68 2,849 (35% ⬎ 90%) — 300

Polytherapy (27% ⬎ 90%) — —

Evans et al. (18) Scotland Sulfonylurea 6 — 67 2,275 87% — —

Melformin 64 1,350 83% — —

Mellkian et al. (19) PBO Monotherapy 6 — 63 ⫾ 15 105 54% — —

Mono to combination 77% — —

Polytherapy 6 — 59 71% — —

PBO Poly to combination 87% — —

Morningstar et al. (20) Canada OHA 36 — — 3,358 86% — —

Rajagopalan et al. (21) PBO OHA ⫹ Insulin 24 — 53 195,400 all 81% — —

28,001 new start 81% — —

Scheclman et al. (22) Clinic OHA ⫹ Insulin 15 8.1 ⫾ 2.0 50 ⫾ 11 810 80 ⫾ 21% — —

Sclar et al. (23) Medicaid OHA 12 — 59 ⫾ 10 975 39%‡ —

Spoelstra et al. (24) Netherland OHA 12 — 63 411 85 ⫾ 15% — —

Venturini et al. (25) HMO Sulfonylurea 24 — 59 ⫾ 11 786 83 ⫾ 22% — —

*Persistance for 12 months; †persistance for 24 months; ‡persistance for 6 months, §adherence rates excluding categorical data. HMO, health maintenance organization; PBO, pharmacy benefit organization.

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 27, NUMBER 5, MAY 2004

Cramer

Table 2—Prospective studies of OHA for type 2 diabetic patients using electronic monitoring

Reference n Population Age (years) Medications Follow-up HbA1c Adherence rate Dose interval*

Mason et al. (26) 21 Clinic — Sulfonylurea 3 months ⬎8% 74.5%

Matsuyama et al. (27) 15 Intervention 84 ⫾ 8 OHA 3 months 12.7 ⫾ 1.9 85.1%

17 Control 12.1 ⫾ 2.6 82.8%

Paes et al. (28) 91 Community 69 OHA 6 months — 67.2 ⫾ 30%

(40 o.d.) 79.1 ⫾ 19% 77.7 ⫾ 21%

(36 b.i.d.) 65.6 ⫾ 30% 40.7 ⫾ 28%

(15 t.i.d.) 38.1 ⫾ 36% 5.3 ⫾ 5%

Rosen et al. (29) 77 Clinic 65 Metformin 4 weeks 7.9 ⫾ 1.1 77.7 ⫾ 18%

Rosen et al. (30) 16 Intervention 63 ⫾ 11 Metformin 6 months 79.3 ⫾ 13%

17 Control 60.7 ⫾ 13%

*Dose interval ⫽ proportion of dose taken within the prescribed number of hours between doses (e.g., b.i.d. ⫽ 12 ⫾ 6 – h interval).

12–24 months included all OHAs in the adherence rates decreased with larger enhancement program (29) to demon-

analyses (11,12). However, a study of numbers of OHA doses to be taken daily. strate that poor adherence can be im-

Medicaid recipients in South Carolina One report showed mean adherence of proved when patients and clinicians are

showed low treatment persistence (39% 79.1 ⫾ 19% for once-daily regimens, aware of the frequency of missed doses.

at 6 months) (23). Three reports (four co- 65.6 ⫾ 30% for twice-daily regimens, and They monitored a series of patients (mean

horts) with smaller proportions (16 – 38.1 ⫾ 36% for three-times daily dosing adherence 78%) (29) to find a group of

49%) of patients remaining on treatment regimens (P ⬍ 0.05) (28). The accuracy of poor OHA compliers (mean 61%) in or-

for 6 –12 months focused on specific drug taking doses at appropriate time intervals der to start with a cohort needing im-

treatments (13,16) and monotherapy/ also decreased (77.7 ⫾ 21% for once- provement. The control group remained

polytherapy (15). Persistence expressed daily regimens, 40.7 ⫾ 28% for twice- unchanged, whereas the group receiving

as days to discontinuation was similar in daily regimens, 5.3 ⫾ 5% for three-times the intervention improved to 79% adher-

the two reports using similar methodol- daily regimens; P ⬍ 0.01). ence (P ⬍ 0.05) with their OHA regimen

ogy (83–105 days) (11,13) but was longer The adherence rate for patients taking (Table 2) (30).

(300 days) in the report with descriptive sulfonylurea was 74.5% using electronic

data (17). monitoring, compared with 92.4% for Insulin

self-reported adherence (26). Matsuyama Adherence rates among the three studies

OHA: prospective studies et al. (27) used electronic monitoring re- that assessed insulin use were not compa-

Three groups performed small prospec- ports to guide clinical decision making. rable because of different methods of

tive studies with electronic dose monitor- Adherence reports for a subset of patients analysis (Table 3). The retrospective data-

ing, with two centers each publishing two were provided to their doctors to assist in base method (21) showed a mean 63 ⫾

reports describing different aspects of the making treatment decisions. The infor- 24% adherence for large cohorts of long-

studies. Adherence rates were more con- mation revealed a need for additional pa- term and new-start adult type 2 diabetic

sistent than was found in the retrospective tient education because of inconsistent insulin users. Adherence rates were lower

database analyses (Table 1). Mean adher- dosing (47% of reports). The control for insulin use than for OHA use (73–

ence with OHAs was in a narrow range of group had several instances of dose in- 86%) in both populations (21). A 10-year

61– 85% during up to 6 months’ observa- creases because the clinician was not follow-up of a large cohort of patients

tion (Table 2). All of the prospective stud- aware that erratic dosing was the problem newly started on insulin found that 80%

ies used MEMS electronic monitoring to rather than low dose. of patients persisted with insulin treat-

determine when doses were taken. Elec- Rosen et al. (29,30) used electronic ment for 24 months (12). Fewer patients

tronic monitoring also demonstrated that monitoring with the MUSE-P medication in the insulin-only group (20%) than pa-

Table 3—Retrospective database studies of insulin use

Age

Reference n Population (years) Follow-up HbA1c Adherence rate

Brown et al. (12) 102 HMO new start — 10 years — Persistence 79.6% at 24 months

Morris et al. (7) 89 Scotland 16 ⫾ 7 12 months 9.4 ⫾ 1.7 33–86% days supply*

9.0 ⫾ 1.5 87–116% days supply*

Rajagopalan et al. (21) 27,274 all PBO 53 24 months — 62 ⫾ 24%

1,323 new start 64 ⫾ 24%

*Days supply ⫽ number of tablet dispensed per prescribed number of times to be taken daily. HMO, health maintenance organization; PBO, pharmacy benefit

organization.

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 27, NUMBER 5, MAY 2004 1221

Medication adherence

tients taking an OHA (31%) discontinued the natural progression of type 2 diabetes adding medication. Rosen et al. (30)

treatment (obtained no refill) during the eventually leads many patients to require screened a clinic population to select pa-

second year of follow-up (11). A study of insulin treatment. The study that evalu- tients with low adherence rates for ran-

children and adolescents presented evi- ated type 2 diabetic patients receiving in- domization to a control group or the

dence that poorer compliers had higher sulin showed 63% of doses taken as MUSE-P intervention. MUSE-P consists

mean HbA1c levels (R2 ⫽ 0.39) (7). They prescribed (21). In one cohort, only 80% of a dialogue between the patient and

calculated an index of days with insulin of patients persisted with insulin for 2 health care provider about daily medica-

obtained from the pharmacy, based on years despite the need for long-term gly- tion dosing structured around their per-

the prescribed dose. HbA1c levels ranged cemic control (12). The detailed analysis sonal record of electronic monitoring data

from 9.44 ⫾ 1.7 for the lowest amount of of a group of children and adolescents (39). This simple technique resulted in a

insulin obtained to 8.98 ⫾ 1.5, 7.85 ⫾ showed that poor adherence with the pre- significant improvement in adherence

1.4, and 7.25 ⫾ 1.0 for the higher cate- scribed insulin regimens resulted in poor rates compared with the control subjects,

gories of adherence, respectively (P ⬍ glycemic control, as well as more hospi- who received the same amount of per-

0.001). Additional information about talizations for diabetic ketoacidosis and sonal attention but not focused on adher-

clinical status demonstrated that 36% of other complications related to diabetes ence. This program has been effective in

patients with poorest adherence were ad- (7). Self-reported insulin use (not in- enhancing adherence in other medical

mitted to the hospital for diabetic ketoac- cluded in this analysis) showed that pa- disorders (39 – 41). However, electronic

idosis (P ⫽ 0.001 compared with patients tients frequently omit injections. In 31% monitoring is not a readily available tool.

with higher adherence rates) and other of women who reported intentionally Several simple measures usually are help-

complications related to diabetes (P ⫽ omitting doses (8% frequently), weight ful in clinical practice, such as once-daily

0.02 compared with patients with higher gain was the reason (36). One-fourth of dosing and combining multiple medica-

adherence rates). Adolescents (10 –20 adolescents reported having omitted tions into the same regimen (e.g., several

years of age) were significantly more some injections during the 10 days before drugs premeal rather than some before

likely to be in the lowest adherence cate- a clinic visit (37). Therefore, clinicians and some with meals). Patients should be

gory and have the highest HbA1c levels cannot assume that patients with either given information about what to do if a

compared with younger and older pa- type 1 or type 2 diabetes are fully compli- dose is missed or if adverse effects are

tients (both P ⬍ 0.001). ant with insulin regimens, even if the con- bothersome, in addition to the purpose of

sequences might be hazardous. the medication (9,10).

CONCLUSIONS — This systematic The second goal of this study was to Similar electronic monitoring sys-

review confirms that many patients with estimate the strength of the association tems for insulin administration are

diabetes took less than the prescribed between adherence and glycemic control. needed to record patterns of insulin use

amount of medication, including both Too few studies included HbA1c levels to by individual patients. This information

OHA and insulin. Given the central im- allow a precise conclusion, although in- could help healthcare providers deter-

portance of patient self-management and terventions that improve self-manage- mine which patients need additional sup-

medication adherence for health out- ment have been associated with better port to achieve consistent glycemic

comes of diabetes care (31), surprisingly clinical outcomes (38). Further research control. Further studies with electronic

few studies were found that adequately is needed to quantify the specific im- monitoring of diabetes medications may

quantified adherence to diabetes medica- provement in glycemic control that might identify and define the characteristics of

tion. The overall rate of adherence with be obtained from improved medication poorly compliant patients to improve

OHA was 36 –93% in retrospective and adherence. Such studies should demon- treatment outcomes. Improved under-

prospective studies. Previous surveys strate the health benefits that may be de- standing of the way patients use medica-

have found that people took ⬃75% of rived from more convenient therapeutic tion could also affect healthcare

medications as prescribed, across a vari- regimens that are being developed for di- utilization. Improved glycemic control

ety of medical disorders (32,33). Decreas- abetes. could reduce overall healthcare costs

ing adherence related to polytherapy and A bright spot among these reports of (42). This has important implications be-

multiple daily dosing schedules also poor adherence and persistence was the cause of the potential to improve the cur-

matched reports from other medical dis- finding that electronic monitoring tools rently poor adherence with all aspects of

orders (32,33). exist to help enhance medication adher- diabetes self-management. Inadequate

This survey adds to the general find- ence for individual patients. One study adherence to medication and lifestyle rec-

ing that adherence rates are not related to demonstrated that doctors and pharma- ommendations by patients with diabetes

the simplicity of regimen, the severity of cists were able to adjust treatment plans may play an important role in adding to

the disorder, or the possible conse- more appropriately when they had elec- the economic burden of the disease.

quences of missed doses. The persistence tronic monitoring data than when they The major drawback of this survey is

with OHAs of 6 –24 months, as seen in used the usual mode of employing only the methodology used for adherence

this survey, suggests that brief treatment laboratory data (27). The difference was analyses in the reports reviewed. A short-

persistence is a major issue that could lead in understanding that elevated glucose or coming in the literature is the lack of stud-

to deleterious health outcomes. These HbA1c levels were related to missed doses ies evaluating interventions to improve

data parallel other chronic medical disor- and not underprescribing. This informa- adherence in which adherence was mea-

ders in which persistence often is ⬍1 year tion avoided changing prescriptions, in- sured using appropriate methods. The

(34,35). Even with good OHA adherence, creasing drug dose, and switching or retrospective analyses used various defi-

1222 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 27, NUMBER 5, MAY 2004

Cramer

nitions of adherence and persistence and mer JA, Spilker B, Eds. New York, Raven 16. Dezii CM, Kawabata H, Tran M: Effects of

different durations of follow-up. Some Press, 1991, p. 209 –224 once daily and twice-daily dosing on ad-

included all patients, whereas others cen- 2. Feinstein AR: On white coat effects and herence with prescribed glipizide oral

sored cohorts based on arbitrary condi- the electronic monitoring of compliance. therapy for type 2 diabetes. South Med J

Arch Intern Med 150:1377–1378, 1990 95:68 –71, 2002

tions. Analyses did not always account for 3. World Health Organization: Report on 17. Donnan PT, MacDonald TM, Morris AD,

patients who changed to another hypo- Medication Adherence. Geneva, World for the DARTS/MEMO Collaboration: Ad-

glycemic agent or were no longer eligible Health Org., 2003 herence to prescribed oral hypoglycemic

for observation because of a change in 4. Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait medication in a population of patents

health insurance. Attempts are underway A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, Mitch W, Smith with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective co-

to define optimum analytic methods for SC Jr, Sowers JR: Diabetes and cardiovas- hort study. Diabet Med 19:279 –284,

retrospective database studies (43). Elec- cular disease: a statement for health care 2002

tronic monitoring studies suffered from professionals from the American Heart 18. Evans JM, Donnan PT, Morris AD: Adher-

small size and observation limited to one Association. Circulation 100:1134 –1146, ence to oral hypoglycaemic agents prior to

OHA. An overall drawback to this review 1999 insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabet

5. Pugh MJ, Anderson J, Pogach LM, Berlow- Med 19:685– 688, 2002

is the lack of an electronic method to itz DR: Differential adoption of pharma- 19. Melikian C, White J, Vanderplas A, Dezii

monitor insulin use. Such devices are cotherapy recommendations for type 2 CM, Chang E: Adherence to oral antidia-

commonly used to record blood glucose diabetes by generalists and specialists. betic therapy in a managed care organiza-

measurements. The development of an Med Care Res Rev 60:178 –200, 2003 tion: a comparison of monotherapy,

electronic monitoring system for insulin 6. Johnson SB: Methodological issues in di- combination therapy, and fixed-dose

dosing would be an important step to- abetes research: measuring adherence. combination therapy. Clin Ther 24:460 –

ward proving better support for individ- Diabetes Care 15:1658 –1667, 1992 467, 2002

uals with poor insulin adherence and 7. Morris AD, Boyle DIR, McMahon AD, 20. Morningstar BA, Sketris IS, Kephart GC,

improving the dialogue between patients Greene SA, MacDonald TM, Newton RW, Sclar DA: Variation in pharmacy prescrip-

and their healthcare providers. for the DARTS/MEMO Collaboration: Ad- tion refill adherence measures by type of

herence to insulin treatment, glycemic oral antihyperglycaemic drug therapy in

The finding that patients prescribed control, and ketoacidosis in insulin-de- seniors in Nova Scotia, Canada. J Clin

an OHA or insulin take less than the pre- pendent diabetes mellitus. Lancet 350: Pharm Ther 27:213–220, 2002

scribed number of doses over long peri- 1505–1510, 1997 21. Rajagopalan R, Joyce A, Smith D, Ollen-

ods of follow-up indicates an urgent need 8. Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, dorf D, Murray FT: Medication compli-

for prescribers to understand that failure Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL: How often is ance in type 2 diabetes patients:

to reduce HbA1c levels might be related to medication taken as prescribed? A novel retrospective data analysis (Abstract).

inadequate self-management. The impli- assessment technique. JAMA 261:3273– Value Health 6:328, 2003

cation is that instead of increasing the 3277, 1989 22. Schectman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD:

dose, changing the medication, or adding 9. Cramer JA: Microelectronic systems for The association between diabetes meta-

a second drug when glucose and HbA1c monitoring and enhancing patient com- bolic control and drug adherence in an

pliance with medication regimens. Drugs indigent population. Diabetes Care 25:

levels are high, clinicians should consider 49:321–327, 1995 1015–1021, 2002

counseling patients on how to improve 10. Cramer JA: Medication use by the elderly: 23. Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL, Dickson

medication adherence. A first step to im- enhancing patient compliance in the el- WM, Kozma CM, Reeder CE: Sulfonyl-

proving adherence is being able to assess derly: role of packaging aids and monitor- urea pharmacotherapy regimen adher-

it. Developing methods that properly as- ing. Drugs Aging 12:7–15, 1998 ence in a Medicaid population: influence

sess medication adherence as a behavior 11. Boccuzzi SJ, Wogen J, Fox J, Sung JCY, of age, gender, and race. Diabetes Educator

that can be modified could provide a clin- Shah AB, Kim J: Utilization of oral hypo- 25:531–532, 1999

ically significant improvement in glyce- glycemic agents in a drug-insured U.S. 24. Spoelstra JA, Stolk RP, Heerdink ER,

mic control for some patients. Although population. Diabetes Care 24:1411–1415, Klungel OH, Erkens JA, Leufkens HGM,

methods are not yet available for routine 2001 Grobbee DE: Refill compliance in type 2

12. Brown JB, Nichol GA, Glauber HS, Bakst diabetes mellitus: a predictor of switching

use, such information could enhance pa- A: Ten-year follow-up of antidiabetic to insulin therapy? Pharmacoepidemiol

tient-clinician relationships by providing drug use, nonadherence, and mortality in Drug Safety 12:121–127, 2003

information to guide individualized self- a defined population with type-2 diabe- 25. Venturini F, Nichol MB, Sung JCY, Bailey

management to support patients. tes. Clin Ther 21:1045–1057, 1999 KL, Cody M, McCombs JS: Compliance

13. Catalan VS, Couture JA, Lelorier J: Predic- with sulfonylureas in a health mainte-

tors of persistence of use with the novel nance organization: a pharmacy record-

Acknowledgments — This project was sup- antidiabetic agent acarbose. Arch Intern based study. Ann Pharmacother 33:281–

ported by Novo Nordisk. Med 161:1106 –1112, 2001 288, 1999

We thank Soren Skovlund for providing 14. Chiechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE: 26. Mason BJ, Matsuyama JR, Jue SG: Assess-

helpful comments. Depression and diabetes. Arch Intern Med ment of sulfonylurea adherence and met-

160:3278 –3285, 2000 abolic control. Diabetes Educator 21:52–

15. Dailey G, Kim MS, Lian JF: Patient com- 57, 1995

References pliance and persistence with antihyper- 27. Matsuyama JR, Mason BJ, Jue SG: Phar-

1. Glasgow RE: Compliance to diabetes reg- glycemic drug regimens: evaluation of a macists’ interventions using electronic

imens: conceptualization, complexity, Medicaid patient population with type 2 medication-event monitoring device’s ad-

and determinants. In Patient Compliance in diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther 23:1311– herence data versus pill counts. Ann Phar-

Medical Practice and Clinical Trials. Cra- 1320, 2001 macother 27:851– 855, 1993

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 27, NUMBER 5, MAY 2004 1223

Medication adherence

28. Paes AHP, Bakker A, Soe-Aagnie CJ: Im- 34. Cramer JA: Consequences of intermittent medication compliance for people with

pact of dosage frequency on patient com- treatment for hypertension: the case for serious mental illness. J Nerv Mental Dis

pliance. Diabetes Care 20:1512–1517, medication compliance and persistence. 187:52–54, 1999

1997 Am J Managed Care 4:1563–1568, 1998 40. Burnier M, Schneider MP, Chiolero A,

29. Rosen MI, Beauvais JE, Rigsby MO, Salahi 35. Avorn J, Monette J, Lacour A, Bohn RL, Stubi CL, Brunner HR: Electronic compli-

JT, Ryan CE, Cramer JA: Neuropsycho- Monane M, Mogun H, LeLorier J: Persis- ance monitoring in resistant hyperten-

logical correlates of sub-optimal adher- tence of use of lipid-lowering medica- sion: the basis for rational therapeutic

ence to metformin. J Behav Med 26:349 – tions: a cross-national study. JAMA 279: decisions. J Hypertens 19:335–341, 2001

360, 2003 1458 –1462, 1998 41. Nides MA, Tashkin DP, Simmons MS,

30. Rosen MI, Rigsby MO, Salahi JT, Ryan CE, 36. Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Wise RA, Li VC, Rand CS: Improving in-

Cramer JA, Inzucchi S: Electronic moni- Aponte JE, Jacobson AM, Cole CF: Insulin haler adherence in a clinical trial through

toring and counseling to improve medi- omission in women with IDDM. Diabetes the use of the Nebulizer Chronolog. Chest

cation adherence. Behav Res Therapy. In Care 17:1178 –1185, 1994 104:501–507, 1993

press 37. Weissberg-Benchell J, Glasgow AM, 42. Menzin J, Langley-Hawthorne C, Fried-

31. Anderson EA, Usher JA: Understanding Tynan WD, Wirtz P, Turek J, Ward J: Ad- man M, Boulanger L, Cavanaugh R: Po-

and enhancing adherence in adults with olescent diabetes management and mis- tential short-term economic benefits of

diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rep 3:141–148, management. Diabetes Care 18:77– 82, improved glycemic control: a managed

2003 1995 care perspective. Diabetes Care 24:51–55,

32. Cramer JA: Partial medication compli- 38. Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, 2001

ance: the enigma in poor medical out- Engelau MM: Self-management educa- 43. International Society for Pharmacoeco-

comes. Am J Managed Care 1:45–52, 1995 tion for adults with type 2 diabetes: a nomics and Outcomes Research, Medica-

33. Claxton AJ, Cramer JA, Pierce C: medica- meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic tion Compliance Special Interest Group

tion compliance: the importance of the control. Diabetes Care 25:1159 –1171, [article online], 2003. Available from

dosing regimen. Clin Ther 23:1296 – 2002 http://www.ispor.org/sigs/medication.htm.

1310, 2001 39. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Enhancing Accessed 17 March 2004

1224 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 27, NUMBER 5, MAY 2004

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Algorithm-ACLS Expanded Systematic Approach 200623Document1 pageAlgorithm-ACLS Expanded Systematic Approach 200623Kavya ShreeNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Off-Label Prescribing For Allergic Diseases in Pre-School ChildrenDocument6 pagesOff-Label Prescribing For Allergic Diseases in Pre-School ChildrenrizkaNo ratings yet

- Botulinum Toxin Off-Label Use in Dermatology: A ReviewDocument18 pagesBotulinum Toxin Off-Label Use in Dermatology: A ReviewrizkaNo ratings yet

- Update On Off Label Use of Metformin For Obesity: Primary Care Diabetes March 2018Document3 pagesUpdate On Off Label Use of Metformin For Obesity: Primary Care Diabetes March 2018rizkaNo ratings yet

- SildenafilDocument12 pagesSildenafilrizkaNo ratings yet

- TRMDLDocument5 pagesTRMDLrizkaNo ratings yet

- Meto DompeDocument6 pagesMeto DomperizkaNo ratings yet

- Patients Treatment Sildenafil 4 12 18Document4 pagesPatients Treatment Sildenafil 4 12 18rizkaNo ratings yet

- Building Performance and Maintenance Information Model Based On IFCDocument17 pagesBuilding Performance and Maintenance Information Model Based On IFCrizkaNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy: 2019 National GuidelineDocument14 pagesHypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy: 2019 National GuidelinerizkaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Management of Low Milk Supply With Domperidone: Separating Fact From Fi CtionDocument2 pagesPharmacological Management of Low Milk Supply With Domperidone: Separating Fact From Fi CtionrizkaNo ratings yet

- Audit Assessment of The FacilitiesDocument17 pagesAudit Assessment of The FacilitiesrizkaNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Resistance: A Rundown of A Global Crisis: Infection and Drug Resistance DoveDocument14 pagesAntibiotic Resistance: A Rundown of A Global Crisis: Infection and Drug Resistance DoverizkaNo ratings yet

- Clinico-Pathological Features of Erythema Nodosum Leprosum: A Case-Control Study at ALERT Hospital, EthiopiaDocument13 pagesClinico-Pathological Features of Erythema Nodosum Leprosum: A Case-Control Study at ALERT Hospital, EthiopiarizkaNo ratings yet

- Topical Clobetasol For The Treatment of Toxic EpidDocument10 pagesTopical Clobetasol For The Treatment of Toxic Epidbella friscaamaliaNo ratings yet

- Algorithm D: Pharmacological Treatment of Chronic Asthma in Children Under 5Document1 pageAlgorithm D: Pharmacological Treatment of Chronic Asthma in Children Under 5samNo ratings yet

- Gambro Phoenix SystemDocument2 pagesGambro Phoenix SystemGraham Thomas GipsonNo ratings yet

- Ptsa 110123Document114 pagesPtsa 110123Zefa FanyaNo ratings yet

- What Is 21 CFR Part 11Document6 pagesWhat Is 21 CFR Part 11Masthan GMNo ratings yet

- Recommended Antibiotic Therapy in Severe Sepsis or Septic ShockDocument4 pagesRecommended Antibiotic Therapy in Severe Sepsis or Septic ShockBoy ReynaldiNo ratings yet

- Drug Study: Date/ Time Ordered Route/Dosage/ Time Interval Precaution Contra-Indications Nursing ResponsibilitesDocument3 pagesDrug Study: Date/ Time Ordered Route/Dosage/ Time Interval Precaution Contra-Indications Nursing ResponsibilitespjcolitaNo ratings yet

- Van Asten ResumeDocument2 pagesVan Asten Resumeapi-499382707No ratings yet

- 2021 Concierge Refill Reminder ScriptDocument15 pages2021 Concierge Refill Reminder ScriptPablo PerezNo ratings yet

- Mult AEREL AEACNDocument7 pagesMult AEREL AEACNBart RoofthooftNo ratings yet

- Sodium Picosulfate For ConstipationDocument2 pagesSodium Picosulfate For Constipationshoukat aliNo ratings yet

- Kubie, L. (1971) - The Destructive Potential of Humor in PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesKubie, L. (1971) - The Destructive Potential of Humor in PsychotherapyMikaelaMundell100% (1)

- Directiva 2001 - 83 CE - Medicament DefinitieDocument4 pagesDirectiva 2001 - 83 CE - Medicament DefinitienicoletagenovevaNo ratings yet

- Soluvit NinfDocument4 pagesSoluvit NinfNurkholis AminNo ratings yet

- Calculate The Max Doses of Local Anesthesia in DentistryDocument13 pagesCalculate The Max Doses of Local Anesthesia in DentistryYasser MagramiNo ratings yet

- 29984-Texto Del Artículo-95858-1-10-20200819Document6 pages29984-Texto Del Artículo-95858-1-10-20200819Alvaro Luis Fajardo ZapataNo ratings yet

- Drug Therapy Problems and Quality of Life in Patients With Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument62 pagesDrug Therapy Problems and Quality of Life in Patients With Chronic Kidney DiseaseAliff Dhurani ZakiNo ratings yet

- Drug DiscoveryDocument6 pagesDrug DiscoveryGaurav DarochNo ratings yet

- LL ALLUZIENCE Liquid Formulation of AbobotulinumtoxinA A 6-MonthDocument13 pagesLL ALLUZIENCE Liquid Formulation of AbobotulinumtoxinA A 6-MonthAnderson GomesNo ratings yet

- Close Loop Medication ManagementDocument25 pagesClose Loop Medication Managementfathul jannahNo ratings yet

- Tranexamic Acid 5tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SMPC) - (Emc)Document1 pageTranexamic Acid 5tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SMPC) - (Emc)incf 1672No ratings yet

- Dosing Instructions For HCGDocument1 pageDosing Instructions For HCGRashika SharmaNo ratings yet

- Deskripsi Barang Komposisi Pabrik: PT - Pharma Indo SuksesDocument20 pagesDeskripsi Barang Komposisi Pabrik: PT - Pharma Indo SuksesAnctho LukmiNo ratings yet

- ALSDocument33 pagesALSsyahrizon thomasNo ratings yet

- Chart FastingDocument1 pageChart FastingGary S75% (4)

- Administration of Inotropes Evidence Based Nursing PolicyDocument8 pagesAdministration of Inotropes Evidence Based Nursing PolicyRonald ThakorNo ratings yet

- Penghitungan Obat Used Syringe PumpDocument31 pagesPenghitungan Obat Used Syringe PumpFregiYuandiNo ratings yet

- Practice Drug CalculationsDocument11 pagesPractice Drug Calculationskijeramustapha23No ratings yet