Professional Documents

Culture Documents

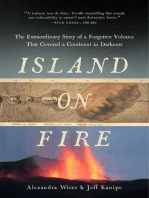

1783 Laki Eruption

Uploaded by

Home Smart TVOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1783 Laki Eruption

Uploaded by

Home Smart TVCopyright:

Available Formats

On 8 June 1783, a 25 km (15.

5 mi) long fissure of at least 130 vents opened with

phreatomagmatic explosions because of the groundwater interacting with the rising

basalt magma. Over a few days the eruptions became less explosive, Strombolian, and

later Hawaiian in character, with high rates of lava effusion. This event is rated

as 4 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index,[5] but the eight-month emission of sulfuric

aerosols resulted in one of the most important climatic and socially significant

natural events of the last millennium.[6][7]

The eruption, also known as the Skaftáreldar ([ˈskaftˌauːrˌɛltar̥], "Skaftá fires")

or Síðueldur produced an estimated 14 km3 (3.4 cu mi) of basalt lava, and the total

volume of tephra emitted was 0.91 km3 (0.2 cu mi).[8] Lava fountains were estimated

to have reached heights of 800 to 1,400 m (2,600 to 4,600 ft). The gases were

carried by the convective eruption column to altitudes of about 15 km (10 mi).[9]

The eruption continued until 7 February 1784, but most of the lava was ejected in

the first five months. One study states that the event "occurred as ten pulses of

activity, each starting with a short-lived explosive phase followed by a long-lived

period of fire-fountaining".[10] Grímsvötn volcano, from which the Laki fissure

extends, was also erupting at the time, from 1783 until 1785. The outpouring of

gases, including an estimated 8 million tons of fluorine and an estimated 120

million tons of sulfur dioxide, gave rise to what has since become known as the

"Laki haze" across Europe.[9]

Consequences in Iceland

The consequences for Iceland, known as the Móðuharðindin [ˈmouːðʏˌharðɪntɪn] (Mist

hardships), were disastrous.[11] An estimated 20–25% of the population died in the

famine after the fissure eruptions ensued. (Some sources specify a death toll of

9,000 people.)[12] Approximately 80% of sheep, 50% of cattle and 50% of horses died

because of dental fluorosis and skeletal fluorosis from the 8 million tons of

fluorine that were released.[13][14] The livestock deaths were primarily caused by

eating the contaminated grass; the subsequent famine claimed many of the human

lives that were lost.[12]

The parish priest and dean of Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla, Jón Steingrímsson (1728–

1791), grew famous because of the eldmessa ("fire sermon") that he delivered on 20

July 1783. The people of the small settlement of Kirkjubæjarklaustur were

worshipping while the village was endangered by a lava stream, which ceased to flow

not far from town, with the townsfolk still in church.

This past week, and the two prior to it, more poison fell from the sky than words

can describe: ash, volcanic hairs, rain full of sulfur and saltpeter, all of it

mixed with sand. The snouts, nostrils, and feet of livestock grazing or walking on

the grass turned bright yellow and raw. All water went tepid and light blue in

color and gravel slides turned grey. All the earth's plants burned, withered and

turned grey, one after another, as the fire increased and neared the settlements.

[15]

Center of the Laki Fissure

Consequences in monsoon regions

There is evidence that the Laki eruption weakened African and Indian monsoon

circulations, leading to between 1 and 3 millimetres (0.04 and 0.12 in) less daily

precipitation than normal over the Sahel of Africa, resulting in, among other

effects, low flow in the River Nile.[16] The resulting famine that afflicted Egypt

in 1784 cost it roughly one-sixth of its population.[16][17] The eruption was also

found to have affected the southern Arabian Peninsula and India.[17]

Consequences in East Asia

In Japan the Great Tenmei famine that was already underway was undoubtedly worsened

and prolonged.

You might also like

- LakiDocument9 pagesLakiBenjamin KonjicijaNo ratings yet

- Lectures on Popular and Scientific SubjectsFrom EverandLectures on Popular and Scientific SubjectsNo ratings yet

- 7 Deadly Environmental Disasters: Dust BowlDocument8 pages7 Deadly Environmental Disasters: Dust Bowlanakui14No ratings yet

- Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the WorldFrom EverandTambora: The Eruption That Changed the WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Volcanic Hazards and PredictionDocument9 pagesVolcanic Hazards and Predictionsoumitra karNo ratings yet

- Disaster!: A History of Earthquakes, Floods, Plagues, and Other CatastrophesFrom EverandDisaster!: A History of Earthquakes, Floods, Plagues, and Other CatastrophesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- The Role of The Pyramids in Melting Glass and MetalsDocument63 pagesThe Role of The Pyramids in Melting Glass and MetalsRichter, Joannes100% (2)

- G9 Science Q3 - Week 2 - Effects of VolcanoDocument51 pagesG9 Science Q3 - Week 2 - Effects of Volcanosanaol pisoprintNo ratings yet

- Climbing Hekla - A Historical Mountaineering Account of Expeditions to IcelandFrom EverandClimbing Hekla - A Historical Mountaineering Account of Expeditions to IcelandNo ratings yet

- Hazardous Volcanic EventsDocument18 pagesHazardous Volcanic EventsMatt ValenciaNo ratings yet

- A Natural Disaster Is A Major Adverse Event Resulting From Natural Processes of The EarthDocument9 pagesA Natural Disaster Is A Major Adverse Event Resulting From Natural Processes of The EarthYham ValdezNo ratings yet

- Which Was The World's Biggest Eruption?Document1 pageWhich Was The World's Biggest Eruption?Andrei NituNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes IIDocument49 pagesVolcanoes IISheila MarieNo ratings yet

- 1972 Iran BlizzardDocument3 pages1972 Iran BlizzardMuhammad Fikri SiregarNo ratings yet

- The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of CivilizationsFrom EverandThe Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of CivilizationsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Volcanoes IIDocument49 pagesVolcanoes IIAsfandyar KhanNo ratings yet

- Volcanic Hazards and Their EffectsDocument5 pagesVolcanic Hazards and Their EffectsYanni MerkhanelNo ratings yet

- DGHDGFBDRTGFBDocument9 pagesDGHDGFBDRTGFBSirf LaundeNo ratings yet

- GeographyDocument13 pagesGeographyhusna ziaNo ratings yet

- It Project - PollutionDocument23 pagesIt Project - PollutionTolulope MadukweNo ratings yet

- Edinburgh Research ExplorerDocument30 pagesEdinburgh Research ExplorerGrace TSAKALA-KOMBONo ratings yet

- Pyroclastic FlowDocument23 pagesPyroclastic FlowKathy Claire Ballega100% (1)

- The Worst Man-Made Environmental Disasters - Science Book for Kids 9-12 | Children's Science & Nature BooksFrom EverandThe Worst Man-Made Environmental Disasters - Science Book for Kids 9-12 | Children's Science & Nature BooksNo ratings yet

- The Positive and Negative Effects of Volcanic Activity by Sam MccormackDocument13 pagesThe Positive and Negative Effects of Volcanic Activity by Sam MccormackMichelleneChenTadle100% (1)

- 10 Worst Man Made Disasters of All TimeDocument4 pages10 Worst Man Made Disasters of All TimeHafizuddinMahmadNo ratings yet

- Atmospheric and Environmental Effects of The 1783-1784 Laki Eruption: A Review and ReassessmentDocument29 pagesAtmospheric and Environmental Effects of The 1783-1784 Laki Eruption: A Review and ReassessmentRoni Marudut SitumorangNo ratings yet

- Climate Change: An Archaeological Study: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Responded to Global WarmingFrom EverandClimate Change: An Archaeological Study: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Responded to Global WarmingNo ratings yet

- Toba LakeDocument8 pagesToba LakeRoselinaNo ratings yet

- Earthing the Myths: The Myths, Legends and Early History of IrelandFrom EverandEarthing the Myths: The Myths, Legends and Early History of IrelandNo ratings yet

- Cataclysmic Eruptions: The Really Big Ones!Document15 pagesCataclysmic Eruptions: The Really Big Ones!bestbryantNo ratings yet

- Marking in Marker Dates: Towards An Archaeology With Historical PrecisionDocument12 pagesMarking in Marker Dates: Towards An Archaeology With Historical PrecisionMason CoyNo ratings yet

- Largest EarthquakesDocument3 pagesLargest EarthquakesMazen A. TaherNo ratings yet

- Eruption of The Volcano Huaynaputina of The Year 1600 AdDocument2 pagesEruption of The Volcano Huaynaputina of The Year 1600 AdRicardo Ugarte DávilaNo ratings yet

- Y6 KrakatauDocument4 pagesY6 KrakatauJohn GoodwinNo ratings yet

- Now You Know Disasters: The Little Book of AnswersFrom EverandNow You Know Disasters: The Little Book of AnswersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- DTRBDRTBDRTBDRTDocument9 pagesDTRBDRTBDRTBDRTSirf LaundeNo ratings yet

- Eruptions and Explosions: Real Tales of Violent OutburstsFrom EverandEruptions and Explosions: Real Tales of Violent OutburstsNo ratings yet

- 2011 East Africa Drought: It Was One of The Most PowerfulDocument4 pages2011 East Africa Drought: It Was One of The Most PowerfulPranali ShindeNo ratings yet

- A Thing in Disguise: The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton (Text Only)From EverandA Thing in Disguise: The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton (Text Only)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Jurnal FixDocument5 pagesJurnal FixEfa OctaviaNo ratings yet

- EarthquakeDocument6 pagesEarthquakeVaibhav DighadeNo ratings yet

- Climate and The Late Bronze Collapse New Evidence From The Southern LevantDocument28 pagesClimate and The Late Bronze Collapse New Evidence From The Southern LevantIshmalNo ratings yet

- FGHJKLDocument4 pagesFGHJKLShinta Amalya RengganisNo ratings yet

- PollutionDocument49 pagesPollutionkailash chandNo ratings yet

- Ktja6819 8047Document4 pagesKtja6819 8047Siti FatimahNo ratings yet

- Natural DisasterDocument4 pagesNatural DisasterdazzlingbasitNo ratings yet

- Smog SpeechDocument7 pagesSmog SpeechRadoslav PashkurovNo ratings yet

- Geography Project: Stratovolcanoes (Composite Volcanoes)Document16 pagesGeography Project: Stratovolcanoes (Composite Volcanoes)Joel DsouzaNo ratings yet

- Funções Ecológicas Do Vulcanismo Do Relevo e Do SoloDocument47 pagesFunções Ecológicas Do Vulcanismo Do Relevo e Do SoloEdir Edemir ArioliNo ratings yet

- Eng8031 6075Document4 pagesEng8031 6075Kimchee StudyNo ratings yet

- Blair PeachDocument1 pageBlair PeachHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- Death of Blair Peach - AftermathDocument4 pagesDeath of Blair Peach - AftermathHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- Death of Blair Peach - BackgroundDocument2 pagesDeath of Blair Peach - BackgroundHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- Alexander of Greece - ReigDocument2 pagesAlexander of Greece - ReigHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- Alexander of Greece - Early Life and Military CareerDocument2 pagesAlexander of Greece - Early Life and Military CareerHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- Alexander of GreeceDocument1 pageAlexander of GreeceHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- LakiDocument1 pageLakiHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- Laki Eruption ConsequencesDocument1 pageLaki Eruption ConsequencesHome Smart TVNo ratings yet

- Bib 53521 PDFDocument40 pagesBib 53521 PDFplyana100% (1)

- Types of Plate BoundaryDocument6 pagesTypes of Plate BoundaryAnn Joenith SollosoNo ratings yet

- Handout For GLY 137 - The DinosaursDocument13 pagesHandout For GLY 137 - The DinosaursAdnen GuedriaNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ ÔN THI SỐ 39Document6 pagesĐỀ ÔN THI SỐ 39Linh PhamNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheet in Science 9 Quarter 3, Week 1-2Document6 pagesLearning Activity Sheet in Science 9 Quarter 3, Week 1-2Rose Ann ChavezNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Marine GeologyDocument28 pagesIntroduction To Marine GeologyRavindr Kumar100% (6)

- Plant SurveyDocument45 pagesPlant SurveyAbu Muhammad Rayyan khanNo ratings yet

- Geological Mapping SymbolsDocument1 pageGeological Mapping Symbols007 CaptJackNo ratings yet

- Definition of Soil The Composition of The SoilDocument39 pagesDefinition of Soil The Composition of The SoilZainab QuddoosNo ratings yet

- Catalog of Apollo 16 RocksDocument1,181 pagesCatalog of Apollo 16 RocksBob AndrepontNo ratings yet

- Geophysical Exploration For GoldDocument13 pagesGeophysical Exploration For GoldAditya KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Md. Yousuf Gazi, Lecturer, Department of Geology, University of Dhaka (Yousuf - Geo@du - Ac.bd)Document20 pagesMd. Yousuf Gazi, Lecturer, Department of Geology, University of Dhaka (Yousuf - Geo@du - Ac.bd)ehabNo ratings yet

- Structural Styles in SeismicDocument22 pagesStructural Styles in SeismicSabrianto Aswad100% (4)

- Dickinson William R. - Solid Earth GeophysicsDocument15 pagesDickinson William R. - Solid Earth Geophysicsh ang q zNo ratings yet

- Pod AllDocument157 pagesPod AllIndah ChrisnindaNo ratings yet

- Geography Chapter4Document21 pagesGeography Chapter4davedtruth2No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Intrusive Igneous RocksDocument39 pagesChapter 3 Intrusive Igneous Rocksroziel A.mabitasan100% (1)

- James Mcnamee,: Broad Longitudinal Tectonic Basin That Is Filled WithDocument7 pagesJames Mcnamee,: Broad Longitudinal Tectonic Basin That Is Filled WithHarold G. Velasquez SanchezNo ratings yet

- Chavez 1Document23 pagesChavez 1Sean PriceNo ratings yet

- Characterization and Evolution of Primary and Secondary Laterites in Northwestern Bengal Basin, West Bengal, India PDFDocument28 pagesCharacterization and Evolution of Primary and Secondary Laterites in Northwestern Bengal Basin, West Bengal, India PDFsoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Geology of Sri Lanka in Relation To Plate TectonicsDocument11 pagesGeology of Sri Lanka in Relation To Plate TectonicsdillysriNo ratings yet

- Quasim Et Al 2017 Geochemistry PDFDocument18 pagesQuasim Et Al 2017 Geochemistry PDFAdnan QuasimNo ratings yet

- EXPLORATION and ULTILATION ENERGY GEOTHERMAL As Development Efforts Renewable Energy 2023Document1 pageEXPLORATION and ULTILATION ENERGY GEOTHERMAL As Development Efforts Renewable Energy 2023muhrizkyalfian15No ratings yet

- Geology of Yangon (Rangoon) Compilation File by Myo Aung MyanmarDocument135 pagesGeology of Yangon (Rangoon) Compilation File by Myo Aung MyanmarwaimaungNo ratings yet

- ArticoloXIIIAEGCongress Torino2014Document5 pagesArticoloXIIIAEGCongress Torino2014jmhs31No ratings yet

- Leapfrog Geo TutorialsDocument99 pagesLeapfrog Geo TutorialsJhony Wilson Vargas BarbozaNo ratings yet

- Well PlanningDocument26 pagesWell PlanningEbenezer Amoah-Kyei100% (1)

- Chapter 13 Earths History VA TEDocument34 pagesChapter 13 Earths History VA TEJulius BorrisNo ratings yet

- SLK WordDocument14 pagesSLK WordIerdna RamosNo ratings yet

- 1613024686TOEFL Reading Practice Set 1Document3 pages1613024686TOEFL Reading Practice Set 1Cheujeu chaldouNo ratings yet