Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Law Ethics and The Utopian End of Human

Law Ethics and The Utopian End of Human

Uploaded by

fakescribdOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Law Ethics and The Utopian End of Human

Law Ethics and The Utopian End of Human

Uploaded by

fakescribdCopyright:

Available Formats

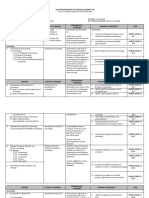

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/274100978

Law, Ethics and the Utopian End of Human Rights

Article in Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing Newsletter, IEEE · June 2003

DOI: 10.1177/0964663903012002005

CITATIONS READS

11 46

2 authors:

Stewart Motha Thanos Zartaloudis

Birkbeck, University of London University of Kent

29 PUBLICATIONS 176 CITATIONS 25 PUBLICATIONS 55 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Thanos Zartaloudis on 12 April 2020.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

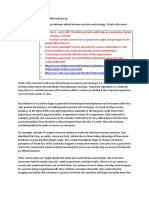

Social & Legal Studies

http://sls.sagepub.com

Law, Ethics and the Utopian End of Human Rights

Stewart Motha and Thanos Zartaloudis

Social Legal Studies 2003; 12; 243

DOI: 10.1177/0964663903012002005

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://sls.sagepub.com

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Social & Legal Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://sls.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://sls.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

REVIEW ARTICLE

LAW, ETHICS AND THE

UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN

RIGHTS

COSTAS DOUZINAS, The End of Human Rights: Critical Legal Thought at the Turn

of the Century. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2000.

STEWART MOTHA AND THANOS ZARTALOUDIS

Birkbeck School of Law, University of London, UK

I. INTRODUCTION

T

HE ‘END OF IDEOLOGY’ apparently ushered in by the demise of the cold

war is accompanied by a new certainty about the ‘measure’ for all time.

This measure or ground for law, justice and the resolution of conflict

is human rights – a paradoxical universal that is at once accomplishment and

aspiration, a means of defining ‘good’ through the negation of ‘evil’ and the

justification for ‘humanitarian bombing’, destructive embargoes and ‘wars

without end’. In this article we engage with perhaps the most sustained

jurisprudential engagement with the philosophical grounds of human rights,

Costas Douzinas’ The End of Human Rights, which attempts to reintroduce

a transcendent justification for the humanity of rights through a genealogi-

cal critique of its erstwhile liberal manifestations.

Douzinas’ principal aim is to set out the philosophical underpinnings of

(another) human rights through the genealogy of radical natural right. Radical

natural right is proposed as a transcendent ground for human rights, but with

the acknowledgement that it is an impossible utopian ideal of a justice ‘to

come’. In this article we interrogate Douzinas’ reliance on Emmanuel

Levinas and Ernst Bloch in his attempt to derive a transcendent ground for

human rights in an allegedly disenchanted postmodern world. Does his

project of establishing a transcendent ground for human rights escape the

SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 0964 6639 (200306) 12:2 Copyright © 2003

SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi,

www.sagepublications.com

Vol. 12(2), 243–268; 033089

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

244 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

violence of the metaphysical presuppositions of law? By this questioning we

mean to explore the extent to which a critique of human rights, which

Douzinas clearly intends, can both denounce the incorporation of human

rights in hegemonic practices and as universalized hegemony, and yet retain

hope and express a meaning of freedom through human rights.

II. HUMAN RIGHTS: GROUNDS OF CRITIQUE WITHOUT CRITIQUE

OF GROUNDS

Human rights are the predominant ‘measure’ for enforcing consensus at the

purported ‘end’ of the ‘ideological battles of modernity’.1 With its selected

application as a gauge of the humanity of an event, action or inaction, it might

be said that human rights has become the ‘ideology at the end of ideology’.

But to deploy the notion of ‘ideology’ as denunciation, whether as mystifi-

cation or falsification or both, is not sufficient to meet the challenges posed

by the rise and rise of human rights (Eagleton, 1991: ch. 1). Given the eman-

cipatory potential claimed for human rights by countless social movements

and political groups it is not easy to merely denounce human rights as a

vehicle of liberal, capitalist triumphalism amid wide-scale hypocrisy. This is

precisely why a sustained critique of human rights is most crucial for the

transgression of the pseudo-universal and ‘proper’ humanity that has rapidly

become the simulacrum of freedom. As Foucault wrote:

Criticism indeed consists of analyzing and reflecting upon limits. But if the

Kantian question was that of knowing what limits knowledge has to renounce

transgressing, it seems to me that the critical question today has to be turned

back into a positive one: in what is given to us as universal, necessary, obliga-

tory, what place is occupied by whatever is singular, contingent, and the

product of arbitrary constraints? (1984: 45)

Indeed, one of the most crucial points of Douzinas’ critique of human

rights is how to conceive of the action of critique (of human rights) in itself.

From our perspective, as Deleuze and Guattari put it:

Rights save neither men nor a philosophy that is reterritorialized on the demo-

cratic state. Human rights will not make us bless capitalism. A great deal of

innocence or cunning is needed by a philosophy of communication that claims

to restore the society of friends, or even of wise men, by forming a universal

opinion as ‘consensus’ able to moralize nations, States, and the market. Human

rights say nothing about the immanent modes of existence of people provided

with rights. Nor is it only in the extreme situations described by Primo Levi

that we experience the shame of being human. We also experience it in insignifi-

cant conditions, before the meanness and vulgarity of existence which haunts

democracies, before the propagation of these modes of existence and of

thought-for-the-market, and before the values, ideals, and opinions of our time.

The ignominy of the possibilities of life that we are offered appears from within.

We do not feel ourselves outside of our time but continue to undergo shameful

compromises with it. This feeling of shame is one of philosophy’s powerful

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 245

motifs. We are not responsible for the victims, but responsible before them.

(1994: 107–8)

To think radically of human rights requires an inquiry into what it means to

criticize. Central to the task of critiquing human rights is the questioning of

what ontological and ethical ground is presupposed under the guise of the

humanism of human rights.

The End of Human Rights is the third volume planned by Costas Douzinas

and Ronnie Warrington as a continuation of their critique of jurisprudence

which began with Postmodern Jurisprudence: The Law of Text in the Texts

of Law (1991) and was followed by Justice Miscarried: Ethics, Aesthetics and

the Law (1994a). Their project reopened the questions of ethics, justice and

critique as the central themes of jurisprudence. We do not provide a compre-

hensive review of their work here but note that one of their paramount

concerns, and indeed one that takes shape as a major trajectory in this third

volume, is an attempt to introduce Levinas’ ‘ethics of alterity’ (for an intro-

duction and exposition of this concept, see Douzinas, 1998; Douzinas and

Warrington, 1994a) and ‘another justice’ (see Douzinas and Warrington, 1994a:

ch. 4) to the discourse of jurisprudence. For Douzinas and Warrington:

Modernity, in destroying any generally acceptable conception of value or virtue

and in disassociating ethics from law, makes justice a central concern of political

theory and the main area of contention of practical politics. But the modern

conception of justice is no longer that of dike,2 the social face of the ethics of

intersubjectivity; it becomes exclusively social justice, an artificial way of

organising the social order when all its traditional bases have been weakened.

(Douzinas and Warrington, 1994a)

The ‘traditional bases that have been weakened’ is not a reference to a ‘previ-

ously existent past long gone’. What they refer to is the a priori ethical obli-

gation that Levinas proposed in his work. For Douzinas and Warrington, this

Levinasian understanding of intersubjectivity (or the ethical relation)

arguably ‘appeared’ prior to the ancient Greek separation between know-

ledge and the right (in the sense of ‘dike’, whereby nature and culture, myth

and logos, subject and community were in juncture, as indistinguishable).

This concern with the ethics of intersubjectivity forms the critical perspec-

tive of Douzinas and Warrington’s critique of law and of the modern (legal)

subject and is largely influenced by Levinas’ ‘ethics of alterity’. As Douzinas

and Warrington state:

[T]he ethics of alterity is a challenge to all attempts to reduce the other to self

and the different to the same [. . .] Moral consciousness is not an experience of

values but the anarchic (an-arche, without beginning or principle) access to a

domain of responsibility and the obligated answer to the other’s demand.

(1994a: 167)

Before considering Douzinas’ reliance on Levinas’ ethics further we shall

briefly outline the themes taken up in this volume.

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

246 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

The principal question of this volume is the possibility of transcendence

in a disenchanted world (p. 15). It is an inquiry that seeks an energy from the

paradoxes that the history of humanism and human rights have to offer; for

instance, the paradox of the two sovereignties of Hobbesian modernity – that

human rights becomes a defence against state power which is itself modelled

on the sovereignty of the individual: ‘[t]he sovereignty of unshackled will

finds its perfect complement and mirror image in the sovereignty of the state.

The Leviathan is the mirror image and the perfect, all too perfect partner of

emancipated man’ (p. 20). That is to say, the ascendance of the ‘autonomous

subject’ is coextensive with the emergence of the mechanism of its subjection

and destruction. Douzinas’ search for a transcendent point from which to

confront these aporias leads him to examine and engage in a genealogical

critique of the tradition of radical natural right.

Part I of the volume thus traces the genealogy of natural law from

its classical beginnings among the Sophists, Stoics, Plato and Aristotle

(pp. 23–45), the renaissance of this classical tradition in Christian natural law

(pp. 52–68), and the maturing of natural right in Hobbes and Locke, the early

thinkers of modernity who produced the hapless individual whose subjec-

tion took the form of the sovereignty of state, nation and people (pp. 69–84).

The revolutions of the 18th century and their respective universal declar-

ations are then exposed as the fount of the paradox of modern humanism:

that the rights and freedoms they inaugurated are ‘groundless’ (pp. 92–5) –

emphasizing the performativity of the proclamations (the undecidability of

whether the declarations created the free and emancipated ‘man’, who, it

seems, would already have to be in existence in order to declare himself free

and emancipated).

This familiar Derridian critique of the ‘speech act’ launches a review of the

polemical critiques of humanism by Burke and Marx that opens part II of

the volume (pp. 147–81). Chapter 7 of the book is a crucial juncture in

Douzinas’ argument as it poses the questions that the genealogy of radical

natural right (part I) provoked, and sets the scene for a philosophical inquiry

into the possibility of human rights as a transcendent ground for a utopian

politicolegal enterprise that has as its ever receding ‘end’, a human rights of

‘the other’. The juridico-philosophical conjunctions by which this critique

of human rights is pursued in part II of the volume will be the focus of the

rest of this article. As already emphasized, Levinas and Bloch are the central

figures in Douzinas’ arguments. We have thus selected these aspects of the

volume for sustained treatment.

Levinas’ ethics emerges through a critique of both Husserl’s and

Heidegger’s thought. We shall open our critique of Douzinas’ reliance on

Levinas with a basic outline of the phenomenological and ontological precur-

sors of Levinas’ thought, Husserl and Heidegger.

Phenomenology is a method, to risk oversimplification, of questioning the

encounter between one’s self, or, to be precise, a consciousness, and the

world. It also involves radically questioning the manner in which the world

is presented to consciousness. As Levinas has put it, phenomenology involves

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 247

the thinking self (a cogito) questioning the so-called ‘natural’ knowledge

available to it about things in the world. The world is made present to a cogito

as various objects, but this representation of the world obscures the thing in

itself. The task of phenomenology is to question how the cogito comes to

know ‘what is’ – ‘how is what is?’ (Levinas, 1985: 30–1).

The modern phenomenological method begins perhaps with Edmund

Husserl’s ambition to provide a liberation of philosophy from naturalist epis-

temology and scientific neutrality (see generally, Husserl, 1970, 1983). For

phenomenologists like Husserl there is no stable essence behind the flux of

perceived phenomena that science can secure and reveal. For Husserl, this

means that the ‘intentional object’ cannot be separated from the conscious-

ness that intends it. The transcendental reduction reveals a transcendental

Ego which is not part of an objective natural ‘world’, but which produces

the perception of what constitutes the knowledge of the world through its

conscious intentionality. The reflexive subject can still assume its primacy in

an intelligible world, yet Husserlian phenomenology also maintains that

there is a primary openness of consciousness to what lies outside it, that is

to a ‘world’, the real. Yet what ‘is’, or ‘being’, is to be seen in the multiplicity

and the non-stable intentional realization of it through consciousness. To

summarize, Husserl gives to phenomenology a method whereby it is

perception that gives us ‘being’ (phenomenological existence), rather than an

atemporal domain (like nature) that is distinct from the experience of

phenomena. Yet, consciousness in its primacy over being remains transcen-

dental in this conception, that is, independent of the historical and experien-

tial situation of a human being.

With Heidegger, an ontological turn is provided for phenomenology.

Heidegger renews the questioning of Being in order to replace, inter alia, the

absolute primacy accorded to consciousness in Husserl which is free and

transcendental, with Dasein (Being-there).3 Dasein is inseparable from its

situatedness in temporality and history. That is, Dasein is immersed in

experience, facticity, contingent reality, time and space. Being can only be

‘understood’, by Dasein, as being historical. Being is the pure transcenden-

tal (yet it is no God or supreme being). Instead of a primacy of conscious-

ness over the world (Husserl), or a primacy of subject over object, for

Heidegger there lies a need to question the perpetual interchange between

Being and being, alterity and presence. And this perpetual interchange is

conditioned only by temporality.

For Levinas, Husserl’s transcendental reduction, given the self-referential

character of intentionality, imprisons thinking in a conscious self through

which all ‘understanding’ must pass. The ‘meaning’ of the other is presup-

posed in the translation of this ‘alien’ object into a meaningful object of inten-

tional experience. The problem with this reduction, from a Levinasian

perspective, is that the ‘thing in itself’ (or the primordial ethical ‘suffering’

that precedes the ‘I’ of consciousness) remains undisclosed. Heidegger’s

rejection of Husserl’s primacy of consciousness enjoys greater proximity

with the Levinasian undertaking. But for Levinas, Heidegger replaces the

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

248 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

transcendental Ego with Being and subsumes the ‘alien’ outside into Being.

Yet, Levinas asks, is the relation of human beings to Being one of ontology?

For Levinas the ethical has primacy over the ontological. According to

Levinas, Husserl thought of the Other as the self’s other, and Heidegger

thought of the Other as the being-with of Dasein. Both then thought the

Other through the same (conscious self or Dasein) while Levinas’ concern is

with a way ‘to think the Other as Other’ (for a basic account, see Davis, 1996;

and for a more advanced outline, Llewelyn, 1995). To quote a crucial state-

ment of this concern:

a calling into question of the same – which cannot occur within the egoistic

spontaneity of the Same – is brought about by the Other. We name this calling

into question of my spontaneity by the presence of the Other ethics. The

strangeness of the Other, his irreducibility to the I, to my thoughts and my

possessions, is precisely accomplished as a calling into question of my spon-

taneity, as ethics. (Levinas, 1969: 43)

For Levinas ‘justice, law, right’ are principles of the I’s conscious dwelling in

the world, while ‘ethics’ is the ‘pure’ transcendental (beyond Being,

consciousness or knowledge) that lies prior (a priori) to any (legal) determi-

nation or response to a claim for justice.

For example, a claim to recognize the torture of a person in an application

for ‘refugee status’ (in itself a reductive category of recognition) that may be

evaluated by an official or in a court of law through legal mechanisms of

‘recognition’ and of ‘passing judgment’ fails to ‘recognize’ the absolute suffer-

ing of the other ‘as such’. In such encounters between the law and the subject,

the ethical ‘Other’ before the law is translated into an object for the law’s

mechanisms of adjudication through the law’s own self-reflexivity (its

Sameness). For Levinas, the absolute ‘Other’ is neither an object of know-

ledge and understanding, nor an unknowable empty shell. This absolute

otherness is prereflexive. It is not ontological (a unifying ground of Being)

but ethical (an ethics that precedes ontology) and hence perhaps a radical

ontology that is characterized a priori by a scission between itself (as Being)

and the ethical ineffable ‘call’ to responsibility (as beyond Being). In this

sense, it is not law, the calculable good, or the ontological ground of Being

that is transcendental-proper, but the ethical ‘going-beyond-oneself’ (beyond

the Same).

Law and justice traditionally conceived will thus encounter the suffering

Other by valorizing his/her ‘essence’; for instance, when a decision is made

between categories of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, where the latter is sometimes

condemned, and at other times the necessary suffering or ‘evil’ is tolerated

or encouraged for an apparently ‘higher’ (i.e. transcendental humanitarian

‘good’) goal. In such calculations the encounter with the other is perceived,

translated and regulated through the violent reduction of the other’s needs

through politically determined categories of (‘good’ and) ‘evil’ (see Badiou,

2001). The political and legal framing of the ‘humanitarian’ bombing of the

Republic of Yugoslavia, the apparent need for the sanctions against Iraq, and

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 249

the recently condemned ‘axis of evil’ are examples of this dynamic of reducing

the other to the perceived moral, political and economic needs determined by

a handful of dominant western nations. The legal regulation of this respon-

siveness through the universalization of rights and law violates the singular-

ity of the unassimilated other, by attempting, ‘violently’ as Levinas suggests,

to ‘do justice’ by imposing an egalitarian principle that is not ethical, but

calculable according to the predefined interests of the system (no matter how

humanitarian the rhetoric of such interventions). An alternative radical ethical

approach suggested by Levinas requires that our obligation or response

towards the suffering of the other remain absolute and hence not valorized

or categorized (between ‘good’ and ‘evil’), but beyond ‘good’ and ‘evil’.

However, this Levinasian presupposition requires scrutiny – a task that

Douzinas does not undertake in any significant detail in this book.

There are two crucial questions that Douzinas has not critically scrutinized.

First, there is the question of to what extent the Levinasian depositioning of

the metaphysics of the Same fails to account for its own resurrection of

potentially yet another (different but still) metaphysical imposition on exist-

ence, action and potentiality. That is, to what extent Levinas not only

presupposes what he attempts to ‘overcome’ (for instance, crucially, the

Heideggerian analysis and the Hegelian dialectic), but also to what extent his

‘Other’, as the absolute exterior to Being, depends on what it aims to over-

throw (Being)? For Douzinas there is no doubt that Levinasian ethics are a

transcendental presupposition (and thus subject to a critique of its condition-

ing as ground), yet, for him, Levinas’ ground is a profoundly different one

(in that it is ethical) from the ontological grounds of modernity (which are

based on cogito, Being, knowledge, power, ideology and so forth; Douzinas

and Warrington, 1994a: 168–71). The Levinasian ethical ground remains a

ground (albeit anarchical) and it claims to be neither ideal (a concept, an Idea)

nor logical (a logos, a ratio, a reason). It does so by ‘receiving’ (unegotisti-

cally as it claims) an absolute responsibility.

While an ethical response to the injustices of (humanitarian) law is urgent

and necessary, in our view the arguable absoluteness of the Levinasian

ground does not recognize (in the way it is preserved as such by Douzinas)

its own weakness and susceptibility to critique. A suspicion remains regard-

ing the potential erection of yet another absolute law (of otherness) to

counter the absoluteness of the present law’s injustices (of sameness). In other

words this Levinasian ground may not remain as an opening but as yet

another closure, this time around the ‘radically other’ rather than the ‘self-

same’. There is great potential in furthering, through a critique of itself, this

conception of the radical other, but only by placing it in the midst of a

critique of its transcendental deconstruction and reconstruction. This is a

recognition that a dialectic between ethics and ontology, no matter how

radical the distance may be between the ethical and the ontological in

Levinasian terms, remains a dialectic of metaphysical logos (discourse) and

metaphysical transcendence. Hence, Derrida’s critique of Levinas in

‘Violence and Metaphysics: An Essay on the Thought of Emmanuel Levinas’

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

250 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

(Derrida, 1978: ch. 4) could have been explored further by Douzinas in this

book, not only in order to explicate the proximity and the problematic

reading of Heidegger by Levinas (for instance his arguable misreading of

Being-with), but also in order to expose the limit of Levinas’ ethics through

what Levinas himself has later acknowledged as a fundamental problem of

his thought – that is, as Derrida argues, the recognition that he aims to expose

the absolute Otherness of the Other through the language of philosophical

discourse that he aims to transcend. When one is attempting to show that the

Other should not be thought as the Same, one is still thinking. What would

then be even more important for Douzinas’ engagement with Levinas would

be to further examine how Levinas in his subsequent writings responds to

Derrida’s critique (and significantly his exposition of the difference of the

absolute Other on the level of language, between what Levinas calls the

significance of saying and the signification of the said).4

The second crucial problem with Douzinas’ engagement with Levinas lies

with the failure to interrogate further the ‘passage’ between an absolute obli-

gation to respond to what is ‘beyond understanding’ and ‘the necessity of

doing justice’. The non-essence of the Levinasian ‘absolute obligation’ to the

other lies, on one possible reading, between the absoluteness of the ‘beyond-

understanding’ of the suffering inflicted upon the other, and Levinas’ concern

for the ‘necessity of justice’ from within the workings of a legal system

(although Levinas himself is quite unclear on this). While justice, for Levinas,

is not a legality, that is a regulatory technique:

[justice] calls for judgment and comparison, a comparison of what is in prin-

ciple incomparable, for every being is unique; every other is unique. In that

necessity of being concerned with justice the idea of equity appears on which

the idea of objectivity is based. At a certain moment, there is a necessity for a

‘weighing’, a comparison, a pondering, and in this sense philosophy would be

the appearance of wisdom from the depths of that initial charity [of ethics], the

wisdom of love. (Levinas, 1981: 129–48)

There is here a paradoxical initiative to traverse the impassable, to penetrate

the aporia that is the Other in the name of doing justice. Through the always

inadequate ‘responsiveness’ of ‘weighing, comparison and pondering’ a legal

system projects and enforces the other to a ‘self’ (a party to a case with finite

interests) that law can recognize as an (allegedly) immanent (self-generating)

system. The extent to which the necessity of ‘weighing’ (a valorizing

judgment) is inevitable according to Levinas remains unclarified. If the only

ethical stance that remains is for the legal system to recognize that its

encounter with the other’s suffering is always ‘partial, valorized, and incom-

plete’ – that is, that the law cannot attend to absolute suffering in itself – then

how much potential resistance to the ‘rotten’ (Walter Benjamin) operations

of law is left before the law reenacts its violence (Benjamin, 1921/1986)? How

will the absolute radicality of the a priori ethical Other maintain itself

with/against the presuppositions of law? To what extent, if any, does

Levinasian radicality remain plausible in the shadow of a history of law’s

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 251

foundations so closely shared with the atrocities justified in the name of

another ‘pure’ transcendence that we have known all too well, that of the

Christian God?5

Killing in the name of human rights remains possible. And today we

witness human rights’ rhetoric as a banal repetition of an obvious facticity of

the violence of law and the violence of both humanism and antihumanism.

Further, notwithstanding the positivization of human rights, the (selective)

setting up of international tribunals, and despite emphasis placed on the

regional and particular, they are not providing any solution to the tragic

denial by the West of its own crimes ‘against humanity’.

III. SUBJECTIVIZATION: BETWEEN THE SELF AND THE OTHER

AND BEYOND SUBJECT-BOUND RIGHTS?

The extent to which Douzinas’ analysis of human rights has been informed

by a Levinasian ethics has been set out above. We argued that Douzinas fails

to consider the implications of the gap between alterity and the attempt to

do justice through legal categories that inevitably ‘sacrifice’ some, and at

times, ‘all’ of the Other (for a penetrating analysis of ‘sacrifice’ in the

administration of rights under the new South African Constitution, see van

der Walt, 2001). Thus the a priori ethics that are meant to inform the ‘imposs-

ible ideal’ (p. 165) of radical natural rights operate in a context where the

subject is already stranded, but offered the utopian hope of a justice to come,

albeit one that will always, perhaps, fail to arrive. There is nevertheless a

‘subject’ (or a humanity) that comes before the law (of rights) (p. 183). In

what follows we discuss how Douzinas accounts for this subject ‘before’

(and of) ‘rights’ and critique the emancipatory possibilities held out for the

subject through (another) human rights.

Douzinas’ account of subjectivization6 is posed in relation to the horizon-

limit postulated between subjectum and subjectus. Subjectum is a concep-

tion of the subject as the predicate for all substance and essence which is

itself not predicated on anything else. Subjectum, then, is the philosophical

hypokeimenon (‘what lies under’) as Aristotle called it (p. 203). Subjectus is

the legal-political subject who is under subjection and submission to the rule

of a sovereign power and/or the political, legal order imposed or seemingly

‘voluntarily’ accepted by the subject as legitimate (p. 217). Douzinas’ allo-

cation of a certain theoretical primacy to subjectum over subjectus indicates

his reception of Heidegger’s critique of the ‘metaphysical urge’ to ask ‘what’

questions (like ‘what is (a) human (subject)?’) (p. 203). The metaphysical urge

(the asking of ‘what’ questions) is usually resolved in metaphysical accounts

by proposing an origin (arche) and an end (telos) and then arranging all

entities and experiences in terms of their distance from that origin (p. 203).

Metaphysicians assume that this origin and the ‘essences’ derived from it

are immediately present to a transcendental Ego or Self, beyond language

and signification (p. 203). Through this, ‘unity is privileged over plurality

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

252 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

and sameness over difference’ (p. 203). Subjectum and the other names given

to it over time (‘essence, substance, the good, God, belatedly, Man, reason,

truth’) (p. 204) is the transcendental principle through which the world is

understood and ordered.

How will this metaphysical urge be avoided in the ‘age’ of human rights

where subjectum is proposed as the arche of law: the Law of law? Does

Douzinas’ project for a ‘Law of law’ as ‘radical human rights’, inspired by

Levinasian ethics and Blochian utopianism run aground as another meta-

physical proposal? To address these questions we must consider Douzinas’

genealogy of human rights and the metaphysics that informs it.

One of the central questions posed in this book – ‘is there a place for tran-

scendence in a disenchanted world?’ (p. 15) – arises out of the apparent post-

modern nihilism where universals have been decried as imperialist and

particulars confine and smother the human subject. Even the possibility of a

human(ism) has barely survived the philosophical critique of its essences that

confine and exclude, or a historicization which exposes the violence and

brutality at its constitutive core. The search for transcendence in this dis-

enchanted world begins with Douzinas reaching back to the classical teleo-

logical world whose natural right is crowned ‘radical natural right’ (p. 44).

Classical justice – whether it was Aristotle’s notion of justice in a static hier-

archical cosmos (pp. 38–44) or Plato’s ideal but functional justice for coordi-

nation and discipline (pp. 33–7, 44) – harboured a potential for domination

by ‘a law-giver from above’. In contrast, the potentiality in physis (nature) to

form the ground of resistance to nomos (law) had been developed by the

Sophists (p. 31). And when physis and nomos were placed in relation, as with

the Stoics, this ‘new natural law’ had the capacity to transgress hierarchical

divides such as that between slave and emperor (p. 31). Physis, then, has

revolutionary potential and signifies movement (p. 44). With this potential-

ity, ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ or ‘essence’ and ‘existence’ cannot be privileged

over each other (p. 29). Natural law is thus the radical ground from which

confining tradition, culture and the past can be resisted in the name of being’s

becoming towards a future utopia that is ‘always yet to come’ – an existence

that is always to be perfected.

According to Douzinas this potential to resist domination through ‘radical

natural rights’ falls foul of the positivism and state formation of modernity.

Unlike the classical conception where law and justice reside together, in early

modernity, justice or right is separated from law. Right is now identified as

freedom from law, from all external imposition upon the individual. With

this move the individual who derived rights from nature was removed from

the ‘social’ order. Communities and social interactions, idealized in the polis

as the zenith of political community, were replaced by the individual who

had rights in a presocial state of nature as with Hobbes and Locke

(pp. 69–84). The social bonds that law reflects and needs for a non-positivist

account of why people obey laws are not to be found in the Hobbesian

theory of modern law. The conceptual removal of ‘community’ in the foun-

dation of modern law is a loss that communities are constantly trying to

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 253

augment through myth. These take the form of race, ethnicity, nation or a

reified culture. The modern community persists through cohering myths (see

Fitzpatrick, 1992, 2001). With ‘Scientific individualism’ and the emergence of

the undivided sovereign self, right becomes a power that belongs to the indi-

vidual – it is not the province of law. This paves the way for utilitarianism

which becomes the measure or limit to the drives of the individual. Law

imposes duties and does not confer power (pp. 72–3).

But what of the 18th-century revolutions that proclaimed the emancipation

of man and declared the inalienable character of universal rights? Among the

many paradoxes of the American and French declarations that Douzinas

identifies, two stand out. The first is that the declarations proclaimed a

groundless freedom (pp. 92–5) or the declarations formed their own ground.

This is the paradox that what was proclaimed and declared had already to be

in existence. As Rousseau famously foretold: ‘men should be prior to laws,

what they are to become through them’ (p. 223). One answer to the paradox

proposed by Douzinas is that the declarations constructed a new polity under

the pretext of ‘uncovering’ or ‘describing’ it: the declarations are ‘performa-

tive statements disguised as constative (p. 93) (see Derrida, 1986). The

constituent assemblies were a new coercive legislative power which posited

law and asserted that this power was grounded on the natural autonomy of

individuals (pp. 92–3). Second, the universals were always already particular.

The universal rights could only be guaranteed by national law. These rights

attached to certain citizens of particular polities and not all humans. They

paradoxically ‘perform’ the foundation of a highly localized sovereignty, and

generate violent nationalisms that exclude others (p. 102). Instead of eman-

cipating, the universal declarations transformed universal natural rights to

nation-centred, positivized human rights (pp. 109–14)

But all of this should come as no surprise in light of the critiques of the

18th-century declarations by Edmond Burke and Karl Marx which Douzinas

provocatively situates together (ch. 7; on Burke see pp. 147–57, and on Marx

see pp. 158–64). For Burke the rights of the declarations were metaphysical,

indeterminant and abstract. Heralding Burke as the founder of ‘communi-

tarianism’ (p. 156), Douzinas prepares the ground for his ‘immanent-

transcendent’ foundation for human rights. This ‘immanent-transcendence’,

as we will see, responds to Burke’s call for a recognition that human nature

is socially determined (p. 154) and Marx’s critique of abstract humanism in

which the human loses her concrete content which is filled with the charac-

teristics of bourgeois egotistic man who is separated from other men and

community (p. 159). Douzinas responds to these critiques of the declarations

by suggesting that:

Right can only be grounded on national and local laws, and traditions and the

declarations of human rights remain a ‘nonsense on stilts’ unless translated into

the culture and law of a particular society. But unless the universalising idea of

human rights retains a transcendent position and dignity towards local

conditions [what we interpret as an immanent-transcendence],7 no valid or

convincing critique of the law can be mounted. Rights are local but can only

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

254 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

be criticised and redirected from the point of view of an unrealised and un-

realisable universal. Right operates as a critical function only against a future

horizon, that of the (impossible) ideal of an emancipated and self-constituting

humanity. (p. 165, comment added)

In this formulation universal rights can have no relevance unless they are trans-

lated into the particular (‘dignity towards local conditions’), but in Douzinas’

formulation, no critique of the particular can be mounted without a transcen-

dent point. Hence Douzinas is proposing an ‘immanent-transcendent’ variety

of human rights to form the basis of any critique of law or social and political

practice. The unrealizability of this ideal – and more problematically for

Douzinas’ argument the unrealizability of critique that follows – is then folded

into a utopian claim (we examine the utopian claim in the fourth section).

It is among these contradictions that Douzinas’ approach to the persistent

questions about the ‘ground of law’ and the source of authority for the

humanism of human rights begins to unravel. On the one hand Douzinas

wishes to take on board the critique of humanism and its metaphysical

ground initiated by Nietzsche and Heidegger (pp. 209–16). On the other

hand he wishes to resolve the persistent conundrum around human rights –

the debate between universalism and relativism – by proposing the politico-

philosophical conjunction of an immanent-transcendence. Is this philosoph-

ically and/or politically persuasive?

The philosophical and political critique of a transcendent humanism is

centred on rejecting its metaphysical violence. The classic metaphysical move

in the discourse of humanism was to determine the ‘essence’ of humanum

through the established interpretations of ‘nature’, ‘history’, and the ‘world’

(Heidegger, 1977: 225; Douzinas, 2000: 211). Humanum was then given

the content of these ‘essential’ traits and juxtaposed with barbarum. Meta-

physical humanism, with its often sexist and Eurocentric content authorized

slavery, colonialism and genocide and is manifested in the current world order

through the new imperial wars of the 21st century, also fought in the name

of humanism and the civilized world.

The metaphysical urge has also presented itself in the debate between

universalism (which advances the unrestrained individualism and freedom of

the atomistic subject) and cultural relativism (which insists on the horizons

set by the community, a communion that obliterates individuality) (p. 212).

To this must be added the emerging discourse of a ‘global community’ which

mixes the universalism of US/Eurocentic values and an insistent communion

from which those who attempt escape will be decried as ‘enemies’ and be

subject to destruction. In the face of these critiques of metaphysics Douzinas

proposes a non-metaphysical approach to human rights. It will be the human

rights that are yet to come – and their ground will be in a non-immanent

community of non-metaphysical humanity (p. 213).

The critique of the metaphysical ground of humanism has left the absence

of a ‘value’ by which debates between universalists/relativists can be

resolved. Douzinas’ response to this is to propose human rights as the ‘end

of civilization’ (p. 214), its revised telos. The non-metaphysical approach to

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 255

human rights is informed by Heidegger’s critique and Nancy’s extension of

this critique into the thinking of community. Defined negatively by

Douzinas, such a conception of human rights would: reject the attempt to

state what is essential about any being(s); not insist on any version of the

good life; not treat people as synthetic entities with disconnected wants; not

construct community by reference to any essential past manifesting itself

through an obedience to tradition but by exposure to the other whose trace

creates self; and assign human rights not because of the ‘arrogance of subjec-

tivity’ but because ‘humans are destined to be near Being and care for the

other entities through which Being is disclosed’ (p. 215). Inspired by Jean-

Luc Nancy, Douzinas writes: ‘[i]t is only after the disappearance of the

society of atomistic subjects that the non-immanent community of singular

beings-in-common will have a historical chance. The community of non-

metaphysical humanity is still to come’ (p. 213). It is through a process of

‘righting’ (p. 216), not as an accumulation of a series of rights determined by

political superiors, but by a new (ethical) normativity informed by the

primacy of the other and given form through a genealogy of radical human

rights that freedom and equality will flower. Does Douzinas escape the meta-

physics of transcendental normativity as a presupposition of human rights?

The key to evaluating Douzinas’ project is to interrogate his notion of

‘immanent-transcendence’ which he offers as a replacement for subject-

bound egotistical rights. The transcendence in ‘immanent-transcendence’ is

the move towards a new ethical normativity. This normativity is informed

by the philosophy of Levinas. As we argued earlier, the Levinasian ethics is

itself in need of critique. Levinas also proposes a radical ontology that may

impose closure around alterity. Despite the ‘other’ remaining beyond under-

standing, Levinas arguably admits a weighing and balancing when confronted

with the necessity of doing justice. Thus the violation of the other is not

overcome. The transcendent ground for human rights that Douzinas articu-

lates through the genealogy of radical natural right is itself subject to para-

doxical limits. And if the metaphysical bind of humanism is also not escaped

or is still to come, then the panacea of rights is only granted the hollow hope

of a utopian ideal. The historical chance of a non-immanent community that

Douzinas would like to see emerge will not arise from nowhere. The undoing

of current modes of social organization and its ideological apparatuses – the

age-old formula of revolution – also presents the conundrum of what limits

will determine the allocation of social goods and the extent of freedom in

community-as-revolutionary-communion. The totalitarian closures that

have decided these questions were never true to the ideals that informed

social transformation. However, the paradox of an impossible ideal to come

hardly offers the revolutionary, the refugee or the erstwhile liberal humanist

an escape from infinite lingering in the antechamber of emancipation.

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

256 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

IV. BETWEEN A RETURN TO HUMANITY AND A RETURN OF

HUMANITY

If radical humanism as an ‘immanent-transcendent’ ideal is the ‘form’ of the

emancipatory ground that Douzinas offers, from where does this new

human(ism) get its content? The ‘dignity toward local conditions’, one aspect

of the double-measure, and the immanence (to law) of immanent-transcendent

rights, is a double source of content. But this community must also be a non-

essential one – a tension that is necessarily (un)resolved by the primacy of

the other (who is beyond understanding) which informs the normative or

transcendent aspect of what Douzinas proposes. Will the measure that

Douzinas advances necessarily have to remain ‘content-less’ (and perhaps in

both senses of the term)?

As Balibar writes, this has been the central question for philosophical

anthropology: on the one hand the symbolic (‘logical’ or ‘singifying’) struc-

tures of representation; and on the other hand, the investigation of the

historicity of the complexus essence-existence of human beings in relation to

their presupposition of Physis, Nature, God, Logos, World, conscience, Law

and otherness (Balibar, 1994). This ‘empirico-transcendental doublet’,

Balibar argues, the difference between empirical individuality and ‘that other

eminent subjectivity’ which alone bears the universal, the ‘transcendental

Subject’, creates the dialectic out of which poststructuralism has attempted

to break free, ‘to transgress’. But to ‘trangress’ what? The question as we

reformulate it, following Nancy, lies between a return to an ideality of

meaning and the return of meaning, of a radically different being of

humanity. The return to such an ideality is still today predominantly

discoursed as a return to the Kantian project, as if in the meantime the

critique of Kantianism never took place (Nancy, 1997). Instead, Douzinas’

questioning for a radical neohumanism would be both enriched but also

problematized further through Nancy’s notion of a return ‘of’ a more open

sense of meaning, ‘of’ humanity, rather than a return to another absolute

ideology of what counts as ‘human’. We are still missing ‘the people’ from

our constructions, as well as a more in-depth questioning of ‘what is a

people?’, ‘who are we?’.

Douzinas’ attempt to transgress the metaphysics of human rights is under-

taken through an endorsement of Heidegger’s reconceptualization of exis-

tential (Sartrean) humanism which the latter undertook by questioning the

being-human of humanism. In the presentation of existential freedom and

subjectivity in Sartre, existence takes priority from essence (that is, to hazard

oversimplification for the moment, the nature of a human being is to create

its historico-political determination herself, and to break away from any

pregiven codes). In this sense, what lies before the creativity as employed by

a human being is nothingness, ‘the absence of all essence’ (p. 198). Sartre,

following Nietzsche in this regard, attaches extreme responsibility to the

creation of values by a human being herself. The only guidance to self-

creation comes with the responsibility of promoting freedom and the

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 257

responsibility for oneself and for others (p. 199). For Sartre, the other person

is ‘a freedom confronting me’ and this encounter is where we find ourselves

(‘with-others’). This existential nothingness can indeed help us capture the

essentialization in liberal human rights as seen in the declarations. The

essence of the human in these postulations of rights creates a code imposing

a specific determination of what it means to be human in order to benefit

from these determined rights. Human rights in this sense create a political,

moral, legal and cultural code of essence that portrays itself as a definitive

and unquestionable formulation of human values. Sartre’s existentialism does

not lead to nihilism but to the need for a passionate struggle against the

arrogant orthodoxy of the universal essence of humanity. Thus, Heidegger’s

critique of Sartre’s prioritization of existence must be approached with care.

Humanism is a common target of both philosophers when seen as an impo-

sition of orthodoxy, of a law that asks and predetermines the question ‘what

is a human being?’. Douzinas shows this: ‘the central indictment is that

humanism, by defining the essence of man once and for all, turns human

existence from “open possibility” into a solidified value that follows the

prescriptions of the metaphysicians’ (p. 210).

The difference between Sartre and Heidegger is that while Sartre thinks

within the dialectic of existence-essence, Heidegger finds in this very use of

the dialectic (no matter which term is prioritized) the same problem: a

determination of priority. For Heidegger another thinking of humanism

requires a distancing from all such types of humanism and antihumanism and

a penetration through the radical question behind both: his inquiry is

conditioned in his early work by Being, and to this extent it can be asked

whether Heidegger himself is not just merely positing another supreme

Sameness in the grounding of human existence. However, one needs to

examine Heidegger’s work further, from ‘Being and Time’ and through to the

later writings. On the basis of these it could be argued that the new, the

potential and the unknown are what lies as a ‘discordant condition in itself’

(for an alternative critical reading of Heidegger, see Zartaloudis, 2002). In

other words, for Heidegger to say with Sartre that nothingness is the

condition of freedom, poses the crucial problem of metaphysical presuppo-

sitions but does not encounter the problem fully. To translate this Heideg-

gerian critique into human rights discourse, both to the humanism of liberals

(as a posited code) and to the (anti)humanism of existentialism (the positing

of an anti-code, nothingness as the lack of human essence) does not think

through the question of the Being of the being-human in itself.8 This question

is nothing other than a reconceptualization of existence in itself beyond the

logic of postulating a (legal) signification on the ‘proper’ of humanity (no

other philosophers today have explored this question with more passion than

J. L. Nancy and G. Agamben).

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

258 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

V. (NON) RECOGNIZING: UTOPIA(N) ENDS?

This volume contains an interesting reading of the Hegelian dialectic of

recognition together with an indication of the limits of its logic of negativity

(pp. 265–73, 280–96). Douzinas relies on the Hegelian dialectic of recognition

to show that:

human rights are expressions of the struggle for recognition amongst citizens

which presupposes and constructs the political community [. . .]; Many aspects

of recognition take the form of rights and all rights are in this sense political:

they extend the logic of public access and decision-making to ever-increasing

parts of social life. [. . .]. Human rights [. . .] (are) signs of a communal acknow-

ledgement of the openness of society and identity, the place where care, love,

and law meet. (p. 295)

There are several questions that emerge in reading Douzinas’ treatment of

the Hegelian dialectic of recognition: first, the very reading of this dialectic

through recognition seems to place a misleading or self-conflicting emphasis

on recognition as a possibility of countering misrecognition. Douzinas amply

demonstrates that recognition is always already a misrecognition, and this is

so in Hegel’s own terms. However, when this is translated into the discourse

of human rights, it seems that the dialectical (im)possibility, of let us say

‘complete recognition’, is utilized not as a cataclysmic criticism of the logic

of recognition, but as a basis for explaining the paradoxes of human rights

discourse and practice (and thus in a sense potentially justifying their failure

in their fantastical overcoming). This is a very Hegelian method of critique.

Hegelianism may dangerously become the magna mater of any attempt to

think otherwise. In this sense too, to remain within Douzinas’s references,

Levinas’ critique of Hegelianism is not explicitly taken up.

A person may attain some recognition through a constitutional regime of

rights but not, as Douzinas shows, ‘full’ recognition of his/her being as a

whole. What this misses as a logic is: first, that partial recognition, by being

always partial and monocular – given that the person’s claim is filtered

through a logic of legal rights – always fails to do what it proclaims (to recog-

nize being ‘as a whole’) (for a consideration of constitutional rights in these

terms, see van der Walt, 2001). Second, the logic of rights through this dialec-

tic of recognition does not and cannot look at the violence and the injustice

of everything that has taken place prior to a claim for recognition within the

predetermined movement of the dialectic. It cannot do that because dialecti-

cal recognition posits a ‘supreme’ system of encounter that always begins

from its predetermined ‘self’ and not from the otherness of a violated being.

It is a dialectic of law that does not address (or ironically recognize) the

violence of its own origin in violence. In this sense, human rights are not

‘the place where care, love and law meet’, because legal recognition is always

partial recognition (if at all) of the dialecticized humanity of a human being.

If one is to follow Levinasian ethics perhaps it could be said that the absol-

utely other resists appropriation or recognition absolutely, prior to the

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 259

violent translation on the basis of the dialectical right claimed before the law.

Resistance comes prior to ‘righting’. ‘Care’ of/by the law is always an impo-

sition of how far this caring for the (violated by the carers) other can go.

A (mis)recognition is a return to a misrecognition in a dialectical circle that

reduces the different to the same identity. That is, the legal system of rights

recognizes only what is predetermined as acceptable on the basis of evalu-

ating the different through a question such as ‘does it meet our definition of

what we share in common, of our common-being, that is of our definition

of the human?’. What the logic of recognition cannot think is thus what

happens to human rights when one accepts that we have no common being,

but that the common (the community) has a ‘being-in-common’ that should

never be metaphysically essentialized. In philosophical terms, Hegel’s dialec-

tic of ‘the desire to become a subject’, as Nancy has argued, is yet again

another will-to-meaning (the logic of signification) and thus it seems to us

that a logic of recognition cannot be maintained after the radical critique of

metaphysics, and of the signification of essence (in this work via Sartre,

Heidegger and Levinas). This does not mean of course that the study of

Hegel’s thought has exhausted its possibilities.

We cannot develop our perspective here in any detail, suffice it to say the

following. The being-form of rights is in our contention always paradoxical,

not because in their paradoxical way they offer a choice between their free

use and their abuse, but because they are the imaginary symbolic constructs

that reinforce the dialectical capacity of the law to maintain itself, to repro-

duce itself in relation to its presuppositions. Instead, we must think towards

what it would mean to think of ‘the free use of freedom (the proper impro-

priety of humanity)’.

What happens to Douzinas’ reading of Hegel when it is seen through his

reading of Bloch’s division between human rights and legal rights? Indeed,

what happens to the dialectical formation when the humanism that delimits

the human of rights has all along been the presupposition that law enforces

in order to reproduce itself as necessary and consensual? These are the ques-

tions we shall explore here. To an extent Douzinas is right when he writes:

‘the legal subject is the creation of positive law and the accompaniment of its

rules, the sovereign plaything and its potential critic, the autonomous centre

of the world as well as the dissident and rebel’ (p. 373). As such, rebellion is

‘of’ law, within law, the other law of ‘its’ supreme dialectical self-same law.

To use another terminology, the legal subject, as both autonomous (the

Enlightenment fantasy of the self-giving-law) and subjected, cannot create a

subjected self and then absolutely renounce it in order to rebel against its

own often monstrous creation (the inevitable necessity of its dialectical legis-

lation). This would run counter to its very form-of-existence and to the

fundamentally ‘necessary’ continuation of rights as a dialectic system.

To rephrase, absolute otherness is instantly reinscribed within this dialec-

tic of (mis)recognition, the moment he/she arrives on the scene, it is thrown

into an indistinction between inclusion-exclusion, so that from within the

dialectic gloss it has its menacing potential effaced as irrational, violent and

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

260 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

unreal and yet ‘recognized’. It becomes a faceless voice within the dialectical

identification of its difference and yet it enjoys a dialectically simulated face

inside-outside it. There lies a question of radically different viewpoints.

From within the dialectic the all-seeing eye covers, uncovers, recovers. From

outside the dialectic (to stay within Douzinas’ discourse – the Levinasian

absolute exteriority), resistance has primacy. From a Levinasian perspective,

the dialectic denies the absolutely different face of the other in its synthetic

unity of the other and the same.

From our perspective no such dialectic superpostulated synthesis (end) can

handle the fragmentation that affects the coherence of a personality or the

multiple narratives that can be generated from the life of one individual. As

G. Deleuze (1988) argues, ‘there will always be a relation to oneself which

resists codes and powers; the relation to oneself is even one of the origins of

these points of resistance’. The multiplicitous-becoming of humanity is not

a dialectic bundle of rights. In Hegelianism this multiple has become a

metaphor for an array of synthesizing concepts centred on the force of the

ordering of needs and the need for order.

Douzinas demonstrates this but also insists on a supra-dialectic of promis-

sory disturbance of the actual state of this ordering. For Douzinas, the prox-

imity-difference to the Hegelian dialectic is best shown in the following

phrase: ‘there can be no real foundation of human rights without an end to

exploitation and no real end to exploitation without the establishment of

human rights’ (pp. 176–7). Is this not an unacknowledged Marxist-Hegelian

dialectic of dehumanization? How will human rights survive the destruction

of the monocular and violent legal rights and the state-based community of

right-holders that emanates from it? What is Douzinas’ utopian disturbance

or difference from the actual?

In close proximity to Derrida’s ‘Messianism without a Messiah’, Douzinas

frames the utopian end as the social aspect of the messianic experience.

Douzinas quotes Derrida who describes the messianic as ‘an irreducible

amalgam of desire and anguish, affirmation and fear, promise and threat . . .

Messianicity mandates that we interrupt the ordinary course of things, time

and history here-now, it is inseparable from an affirmation of otherness and

justice’ (Derrida, 1994: 378). In our eyes, utopia is es gibt (the gift) of a dialec-

tic sacrifice, and the messianic becomes the ‘disruption-recovery’ of its trace.

For Douzinas the end of human rights is both a messianic eschatology that

never arrives, a promise that is always yet to be realized, and also a begin-

ning, a ‘future anterior’ that is the possibility of human emancipation through

the radical potential of human rights (pp. 336–42). This utopian promise of

human rights is opposed to any universal ideal akin to a Kantian moral law

(p. 195). The alterity of the other, which Douzinas elaborates through Drucilla

Cornell’s notion of the ‘imaginary domain’ (we have examined the Levinasian

aspect of this above), renders any universal position or characterization of

the whole person as a ground for legal intervention illegitimate. The projec-

tions of the ‘imaginary’ (each person’s imagination of who he/she is) defer

from person to person. The existential integrity of each person is held

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 261

together by a fantasy of completeness which allows each particular being to

create ‘fragile narratives of biographical coherence out of the many “subject

positions” and disconnected fragments of [their] existence’ (p. 337). For

Douzinas, human rights plays a central role in constructing this fantasy, for

the hope of freedom and equality, the central values of human rights, are

carried in the fantasy and help to ‘inscribe the utopian but indispensable

promise of integrity onto self and the body politic’ (pp. 337–8, 378–9).

This future anterior of anticipated bodily completeness, which Douzinas

draws from Lacanian psychoanalysis and Drucilla Cornell, is then linked to

Bloch’s utopianism, a revival of radical natural rights as the basis of utopian

hope. According to Douzinas’ amalgamation of these theoretical insights, we

conceive of ourselves on the one hand as beings who are fractured and

dismembered by the allocation of socially and historically constructed differ-

ence and oppression, and on the other hand as harbouring the potential for

transcending this allocated (dis)embodiment, not as abstract bearers of rights

but as the beings capable of experiencing freedom based on individual

integrity. This formulation expresses the central regulative ideal presented in

this book: human rights as an immanent-transcendent ideal. The concept of

an immanent-transcendent ideal of human rights is a means of bridging what

is a familiar gap between the empirical and the ideal – an approach that brings

Douzinas strikingly close to Jacques Derrida’s treatment of the ideal as end

in Specters of Marx (Derrida, 1994: 61–75, 86–7).

Derrida and Douzinas refer to the gap in Francis Fukuyama’s thesis on the

end of history. In Fukuyama’s triumphant announcement of the end of

history he asserts that the ideal of liberal democracy and human rights have

finally been realized. There is of course a gap between this ideal and the

present empirical reality that ‘never have violence, inequality exclusion,

famine and thus economic oppression affected as many human beings in the

history of the earth and humanity’ (Derrida, 1994, 85; Douzinas, 2000: 339,

378). On Derrida’s account, despite the historical inadequation of a regula-

tive ideal, a Marxist critique remains urgent and necessary for at least two

reasons: first, in order to reduce the gap as much as possible, ‘in order to

adjust “reality” to the “ideal” in the course of a necessarily infinite process’;

and second to put into question the very concept of the ideal (Derrida, 1994:

86–7).9 This paradoxically maintains the ideal, whether it be the human of

human rights or democracy, as a horizon to come.

The formulation of this horizon to come through the concept of

immanent-transcendence by Douzinas attempts both to preserve the presup-

position of the ideal but also to adjust the ideal to reality – that is to the

alterity of a multitude of particulars and their many rationalities to come

(p. 165). There is a certain end of history in this formulation – the end of the

history of the abstract human – the end of adjusting the actual to the ideal.

In this Douzinas is proximate to Kojève:

which means that even while he speaks from now on in an adequate fashion of

all that he has been given, post-historical Man must/should [. . .] continue to

detach [underscored by Kojève] ‘forms’ from their ‘contents’, doing this not in

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

262 SOCIAL & LEGAL STUDIES 12(2)

order to transform the latter actively, but in order to oppose himself [underlined

by Kojève] as a pure ‘form’ to himself and to others, taken as whatever sorts

of ‘contents’. (Kojève, 1947: 437; Derrida, 1994: 74)

Derrida offers a reading of this passage that resonates with Douzinas’

messianic eschatology of the end of human rights:

The ‘logic’ of the proposition just quoted . . . [Kojève above] . . . might indeed

correspond to a law, the law of the law. This law would signify the following to

us: in the same place, on the same limit, where history is finished, there where

a certain determined concept of history comes to an end, precisely there the

historicity of history begins, there finally it has the chance of heralding itself –

of promising itself. There where man, a certain determined concept of man, is

finished, there the pure humanity of man, of the other man and of man as other

begins or has finally the chance of heralding itself – of promising itself. In an

apparently inhuman or else a-human fashion. Even if these propositions still call

for critical or deconstructive questions, they are not reducible to the vulgate of

the capitalist paradise as end of history. (Derrida, 1994: 74; emphasis in original)

In Douzinas’ formulation there is a conflation of end as messianic eschatol-

ogy, the hope of a yet to come, and the end as a beginning, the future anterior

which is the imagining of an emancipated human through the radical norma-

tivity of human rights. Being (human) is becoming (human), there is a unity

of essence and existence. But this remains rather unclear in this volume.

For Douzinas, human rights, reading Bloch, are the utopian element behind

legal rights. Human rights entail two sources, in Bloch’s analysis, on the one

hand, there is dominium (legal dominance over things and people, posses-

sion and property) and on the other hand there are human rights as adopted

by the oppressed (pp. 244–5). This is based on the natural law heritage that

Bloch elevates over and against the positivization of liberal rights. For Bloch,

however, natural law provides a ‘sober mode of anticipation’ for justice, in

contrast to the ‘enthusiastic mode of anticipation’ of social utopias. Natural

law does not coincide with justice, but is the banner of those attempting to

achieve justice towards a concrete (not abstract) just society. The problem,

however, is that ‘in modernity with the extensive positivization of human

rights, the external division between legal and human rights has been repli-

cated in the body of human rights themselves’ (p. 244).

Thus, the utopian element is always-already framed in the language of

rights. A peculiar juridical-linguistic framing, if the future anterior of utopia

is to maintain its potentiality. It is always already a return-to-rights, as it

seems, always already, rather than an affirmation of multiple potentialities of

struggle. The ‘here-now’, is the present-presence as a presupposition of such

circularity, which (de)limits actuality and potentiality to the technology of

rights. This is why, as Deleuze and Guattari suggest, human rights remain

axioms, or in Nietzschean terms, human rights remain the impure mixture

(of a becoming with history: the present; Deleuze and Guattari, 1994).

Utopia as the end of rights is such a mixture, and as Deleuze and Guattari

write, ‘even when opposed to history it is still subject to it and lodged within

Downloaded from http://sls.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 14, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

MOTHA & ZARTALOUDIS: UTOPIAN END OF HUMAN RIGHTS 263

it as an ideal or motivation’ (1994: 110). It would require a wholly separate

work to indulge this radical ontological critique of the present, yet suffice it

to hint at the following: ‘history grasps the event in its effectuation in states

of affairs or in lived experience, but the Event in its becoming escapes history’

(1994: 110). Utopias are hyperactive machines of desire reproduction. As

desire is reproduced, and not any longer poetically (creatively) resistant, it

produces itself as the spectacle of the democratic market. If there is a

universal state, to paraphrase Deleuze and Guattari (which there is not), then

it enjoys the form of a market-cracy, which is the only universal thing in capi-

talism (1994: 110).

The difference that Douzinas aims to redirect between classical utopian

(identified) ends, and the Blochian open-endedness as combined with an

impossible epiphany, is to be seen as ‘transcendent-immanent’. Utopianism

for Bloch is transcendent without transcendence:

it [Utopia] is rectified – but never refuted by the mere power of that which, at

any particular time, is. On the contrary it confutes and judges the existent if it

is failing, and failing inhumanly; indeed, first and foremost it provides the

standard to measure such facticity precisely as departure from the Right; and

above all to measure it immanently: that is, by ideas which have resounded and

informed from time immemorial before such departure, and which are still

displayed and proposed in the face of it. (Geoghegan, 1996: 145)

Utopianism is not confined, in addition, to ‘The’ utopia but to a multiplicity

of forms as ‘a free-floating energy’. It is transcendent(al) as to its utopian

movement from both viewpoints of (other) origin and (open) end; and

immanent as to its means from both viewpoints of ethical-primacy in the

radical-break-of-the-ontologization of the self, and of the paradoxical ontolo-

gization of the rights-bound subject. For the overcoming of both certainty

and uncertainty in the present and of the present, indeterminacy and the

opening (which really should mean the giving-up of the ends-discourse) of

(utopian, or in different terms, potential) ends, is the forming-energy of ques-

tions we need to ask. While there is great value in not thinking of the future

as predetermined and static, this on its own will not suffice for a utopian

project to unravel its potential. Indeed, if Bloch ‘fails’, as Douzinas acknow-

ledges, to avoid later giving primacy to natural rights over utopia, then one

may need to further question to what extent a mere reversal of primacy here

suffices as an argument against the injustices of rights in the present. In

addition, if Bloch’s utopia becomes the wholeness of a multiplicity of

energies that resist the present, this wholeness risks becoming totalized

(hence predetermined), exactly against the ‘spirit’ of what it aims to over-

throw. As Adorno famously put it, ‘for just as there is nothing between

heaven and earth that cannot be seized upon psychoanalytically as a symbol

of something sexual, so there is nothing that cannot be used as symbolic

intention, nothing that is not suitable for a Blochian trace, and this every-