Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions - Cowan&Bellhouse

Uploaded by

poula mamdouhCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions - Cowan&Bellhouse

Uploaded by

poula mamdouhCopyright:

Available Formats

Society of Construction Law

(Gulf)

30 November 2010

API Auditorium, Dubai

Advising on Construction Contracts in

Civil Law Jurisdictions

Paul Cowan, Partner, White & Case, London

John Bellhouse, 9 Gray’s Inn Square, London

Introduction & Summary

I. Background

The Common Law World / the Civil Law World

The Evolution of Civil Law

Comparison of Key Elements

Sources of Law

II. Key Differences of Principle

Interpretation of Contracts

Good Faith

III. Typical Construction Issues

Remedies for Delay

Delay Analysis

Change in Circumstances

Quantum

IV. Different Approaches to Procedure

Common Law Procedure

Civil Law Procedure

Combining the Two: International Arbitration 30 November 2010 2

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

I. Background

A. Common Law World / Civil Law World

Common law Jurisdictions:

England & Wales (plus Ireland and – largely – Scotland)

Commonwealth e.g. Australia, India (Canada – but not Quebec)

U.S.A.

Civil law Jurisdictions:

All other European jurisdictions

Most Central and Latin American jurisdictions

Middle East, plus some African and Asian jurisdictions

Not Homogenous in either Common law or Civil law

Substantive differences in development of common law post-independence

Different philosophies of civil law e.g. the French Civil Code vs. the German Civil Code

30 November 2010 3

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

I. Background

B. The Evolution of Civil Law

The French Civil Code (Napoleonic Code) The German Civil Code

Enacted 1804 Enacted 1900

Conservative and formalistic More modern, less prescriptive

Incorporated in Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy, Incorporated in Austria, Switzerland,

Spain, Louisiana (U.S.A), Quebec (Canada) Greece, Portugal, Turkey, Japan, South

and former colonies Korea and the Republic of China (Taiwan)

The U.A.E. Civil Code

Inspired by Prof. Al-Sanhuri’s Egyptian Civil

Code (which was principally based on the

French Civil Code)

30 November 2010 4

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

I. Background

C. Comparison of Key Elements

Civil law Common law

Based on Roman Law Based on custom

Process of codification System of precedents

Abstract & theoretical Pragmatic & applied

Closed Open

Start with the parties’ agreement More emphasis on freedom of

(pacta sunt servanda) but more contract

mandatory requirements which can

override this

30 November 2010 5

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

I. Background

D. Sources of Law

Civil law Common law

The civil code (!) Case law

Central figure: the legal scholar Statute law

Decided cases have a secondary Case law is of central importance

status

30 November 2010 6

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

I. Background

D. Sources of Law (Cont’d)

Rapprochement of the two legal traditions:

(a) European Union

International Treaties e.g. Treaty of Rome

Direct application of E.U. Directives / Increased use of statute law

(b) More Generally

Conventions e.g. U.N. Convention on the International Sale of Goods

Uniform Rules (e.g. UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts)

Increasing reference in civil law jurisdictions to decided court cases as

persuasive authority and as a secondary source of law

30 November 2010 7

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

II. Key Differences of Principle

A. Interpretation of Contracts

Fundamental Difference in Interpretation:

Common law: Objective standard

Primary focus on the words in the contract

Civil law: Subjective standard

Primary focus on the wider context and intentions

30 November 2010 8

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

II. Key Differences of Principle

A. Interpretation of Contracts (Cont’d)

Common law: Objective standard

Look first at the express words in the contract itself (“The document should, so

far as possible, speak for itself.” – Chartbrook v Persimmon Homes [2009],

paragraph 36)

Strong emphasis on freedom of contract and giving effect to the terms agreed

upon by the parties

If there is ambiguity, the factual background may be considered

Result = Parol evidence rule (at least under English law)

30 November 2010 9

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

II. Key Differences of Principle

A. Interpretation of Contracts (Cont’d)

Common law: Objective standard

Parol evidence rule

“in my opinion then, evidence of negotiations, or of the parties’ intentions and a

fortiori of [the Plaintiff’s] intentions, ought not to be received, and evidence

should be restricted to evidence of the factual background known to the parties

at or before the date of the contract, including evidence of the “genesis” and

objectively the “aim” of the transaction”

Lord Wilberforce in Prenn v Simmonds [1971] 1 WLR 1385

Result: Courts not interested in witness testimony on “I meant it to say this…”

30 November 2010 10

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

II. Key Differences of Principle

A. Interpretation of Contracts (Cont’d)

Civil law: Subjective standard

Start with the words the parties have used but you may also look at the wider

context – e.g. Article 1156 of the French Civil Code:

“One must in agreements seek what the common intention of the contracting

party was, rather than pay attention to the literal meaning of the terms”

Evidence of negotiations is admissible as evidence of the parties’ intentions

Interest of fairness (over freedom of contract)

Mandatory provisions in the Civil law cannot be excluded (e.g. liability for acts of

intentional misconduct / “gross negligence”)

Tribunals have more discretionary powers to intervene to re-write the parties’

agreement

30 November 2010 11

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

II. Key Differences of Principle

A. Interpretation of Contracts (Cont’d)

Common law: Moving towards the civil law position?

Recent remark given by Lord Hoffmann in Chartbrook v Persimmon Homes

[2009], paragraph 33:

“it would not be inconsistent with the English objective theory of contractual

interpretation to admit evidence of previous communications between the parties as

part of the background which may throw light upon what they meant by the language

they used…They may be inadmissible…but not always”

Comparison with French law at paragraph 39:

“French law regards the intentions of the parties as a pure question of subjective

fact…uninfluenced by any rules of law. It follows that any evidence of what they said

or did, whether to each other or to third parties, may be relevant to establishing what

their intentions actually were… English law, on the other hand, mixes up the

ascertainment of intention with the rules of law by depersonalising the contracting

parties and asking, not what their intentions actually were, but what a reasonable

outside observer would have taken them to be”

30 November 2010 12

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

II. Key Differences of Principle

A. Interpretation of Contracts (Cont’d)

Lord Hoffman (cont’d at paragraph 42)

“The rule excludes evidence of what was said or done during the course of negotiating the

agreement for the purpose of drawing inferences about what the contract meant. It does

not exclude the use of such evidence for other purposes, for example, to establish that a

fact which may be relevant as background was known to the parties, or to support a claim

for rectification or estoppel. These are not exceptions to the rule. They operate outside it”

Looking at such background evidence can evidently also be used to influence the

objective interpretation, per Baroness Hale (paragraph 99):

“But I have to confess that I would not have found it quite so easy to reach this conclusion

had we not been made aware of the agreement which the parties had reached on this

aspect of their bargain during the negotiations which led up to the formal contract. On any

objective view, that made the matter crystal clear”

Final destination – parol evidence rule maintained, but can still look at the material

30 November 2010 13

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

II. Key Differences of Principle

B. Good Faith

English common law: no general duty of good faith (cf. other common law jurisdictions e.g. U.S.A.):

“There is no general doctrine of good faith in the English law of contract. The [injured parties] are free to

act as they wish provided they do not act in breach of a term of the contract” (James Spencer v Tame

Valley Padding (1990) CA – per Potter LJ.)

Civil law jurisdictions: parties are expected to act in good faith

French law (both pre-contractual and in the performance of the contract) :

Article 1134: “Agreements lawfully entered into take the place of the law for those who have made

them…They must be performed in good faith” (interpreted as applying to pre-contractual conduct as well)

Article 1135: “Agreements are binding not only as to what is therein expressed, but also as to all the

consequences which equity, usage or statute give to the obligation according to its nature”

U.A.E law:

See, e.g., Article 246: “The contract must be performed in accordance with its contents, and in a manner

consistent with the requirements of good faith”

How much difference does it make?

Common law – no general duties of good faith but analogous remedies in many areas (e.g. estoppel,

misrepresentation, deceit)

Civil law – a contracting party cannot claim more than it contracted for but, if acting in bad faith, it may be

deprived of its ability to enforce certain rights under the contract and / or be exposed to greater damages

30 November 2010 14

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

International construction contracts follow a common pattern

Historical background of international construction forms is common law

(e.g. English ICE forms evolving into the international FIDIC forms)

Construction issues are (largely) the same the world over

When considered in a civil law context, some issues will be analyzed differently to

the common law approach; others may end at the same conclusion through

different means

For example:

(A) Remedies for delay

(B) Delay analysis (time at large; concurrent delay)

(C) Change in circumstances / frustration / force majeure

(D) Quantum (global claims)

30 November 2010 15

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues (Cont’d)

However, before assessing how the civil law will determine the issue, a key

question to consider is whether the contract is “administrative” or

“commercial”

Can make a significant difference to how the contract is applied and / or

how the issue is determined

U.A.E. law – where one of the parties is a public body, the contract may be

construed to be an “administrative contract”

Consequence: the court may have less power to intervene in an

administrative contract and / or the public body may have additional rights

Will see this in some of the particular examples…

30 November 2010 16

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

A. Remedies for Delay

Almost all international construction contracts provide for Liquidated

Damages (LDs) for delay to completion

Under English common law principles, the LDs will be applied regardless

of the actual losses being suffered (provided they were a reasonable pre-

estimate of loss at the time the contract was made)

Thus: if the Owner suffers greater loss, he is limited to the amount of LDs

(typically limited to an overall cap); if his loss is lower, he can still recover

the amount of LDs

Civil law codes typically take a different perspective on this, including wider

powers and discretions for the court or tribunal

30 November 2010 17

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

A. Remedies for Delay (Cont’d)

Example: French Civil Code

French courts have the power to reduce or increase the amount of the LDs

stated in the contract (referred to as “penalties” under French law) when they

appear to be manifestly excessive or derisively low

Article 1152: “Where an agreement provides that he who fails to perform it shall

pay a certain sum as damages, the other party may not be awarded a greater sum.

Nevertheless, the judge may even of his own motion, moderate or increase the

agreed penalty, where it is manifestly excessive or derisively low. Any stipulation to

the contrary shall be deemed unwritten”

This power used to be limited only to LDs in civil / commercial contracts, but

French law has now extended this to administrative contracts

30 November 2010 18

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

A. Remedies for Delay (Cont’d)

The French courts take into account various factors when considering

whether to reduce or increase penalties:

the existence and amount of actual damages suffered as a result of the delay –

e.g. are the LDs “manifestly excessive” as compared with the actual losses

being suffered;

the value of the contract;

whether changes in the project required a time extension; and

the degree to which the party has failed to perform (e.g. deliberate failure might

entail higher levels of damages – “good faith” duties making a difference).

This is a much wider discretion than under the English common law

(although, in practice, it is difficult to persuade the French courts to exercise

these powers)

30 November 2010 19

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

A. Remedies for Delay (Cont’d)

Further Example: U.A.E.

As a matter of practice, LDs in administrative contracts are normally pre-defined and not

subject to negotiation. By contrast, in a commercial or civil contract, the parties typically

reach their own agreement on the amount of liquidated damages

U.A.E courts are entitled to modify the amount of LDs to ensure that it is equal to the actual

loss suffered – Article 390(2) of the U.A.E. Civil Code:

“The judge may in all cases, upon the application of either of the parties, vary such agreement so as

to make the compensation equal to the loss, and any agreement to the contrary shall be void”

But administrative contracts are treated differently from commercial contracts in practice

(commercial contracts: LDs may be increased or decreased; administrative contracts: LDs

may only be reduced)

Also, under civil law systems generally, LDs limitations can be exceeded where a party has

acted with intentional misconduct and / or “gross negligence”

30 November 2010 20

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

B. Delay Analysis

English common law (as with U.S.A. and Commonwealth common law)

contains considerable case law on various issues of delay analysis

Civil law codes and doctrine typically do not contain such specific bodies of

law on these detailed areas of construction practice

Whilst the underlying principles may be different (e.g. the “prevention

principle” will not be recognized as such in civil law), the degree of logical

analysis of basic issues in the common law can be used to persuasive effect

in civil law contexts

For example:

a) “Time at large” (e.g. principles of contract certainty, substantial performance

and good faith in administering the contract); and

b) Concurrent delay (e.g. apportionment of damages to take account of different

causative effects, e.g. Article 290 of the U.A.E. Civil Code)

30 November 2010 21

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

C. Change in Circumstances: Force Majeure, Frustration, General

Hardship

i. Force Majeure

No defined meaning in common law; therefore extensive contract

provisions. Typically, an event beyond a party’s control which prevents any

particular obligations from being performed

In civil law, force majeure exists separately to the contract i.e. protection

even where there is no force majeure provision

ii. Frustration

An external event which renders performance of the contract substantially

impossible

A common law doctrine permitting termination of the contract, but no

liability for damages

30 November 2010 22

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

C. Change in Circumstances: Force Majeure, Frustration, General

Hardship (Cont’d)

iii. General Hardship

In the common law, there is no ability to adjust a contract to changing circumstances

unless the contract contains a provision to this effect (e.g. Tandrin Aviation v Aero Toy

Store (2010))

Civil law usually provides a basis on which a contract may be adjusted to reflect

significant changes to the economic equilibrium of the contract

For example, Article 249 of the U.A.E. Civil Code:

“If exceptional circumstances of a public nature which could not have been foreseen occur as

a result of which the performance of that contractual obligation, even if not impossible,

becomes oppressive for the obligor, so as to threaten him with grave loss, it shall be

permissible for the judge, in accordance with the circumstances and after weighing up of the

interests of each party, to reduce the oppressive obligation to a reasonable level if justice so

requires, and any agreement to the contrary shall be void”

See also Article 248 of the U.A.E. Civil Code (“unfair provisions”)

Similarly, Article 6.2.2. of the UNIDROIT Principles provides for relief from hardship:

“where the occurrence of events fundamentally alters the equilibrium of the contract either

because the cost of a party’s performance has increased or because the value of

performance a party receives has diminished”

30 November 2010 23

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Typical Construction Issues

D. Quantum

English law and most other common law jurisdictions have imposed reasonably

strict requirements for claimants to prove cause and effect in order to recover

damages (e.g. Wharf Properties v Eric Cumine (1991))

The case law on “global claims” has reflected this (although more recent

indications of a more permissive approach e.g. John Doyle v Laing (2004))

Civil law jurisdictions do not typically have any specific provision or doctrine on

“global claims” as such (e.g. in the U.A.E, the courts require the claimant to provide

supporting evidence for each and every element under the claim)

However, it may be possible to use other provisions which are included in some

civil codes to support global claims

For example: Article 1332 of the Peruvian Civil Code:

“If the damage could not be proven in its exact amount, such amount shall be

determined by the judge through equitable quantification”

30 November 2010 24

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

IV. Different Approaches to Procedure

A. Common Law Procedure

As well as substantive differences, the legal traditions of the common law and

civil law give rise to distinct differences of approach in matters of dispute

procedure (derived from national court practice)

Common law

The procedure is “adversarial”

More emphasis is on the parties for the collection of evidence and presentation of their

case

Extensive document discovery

More reliance is put on fact evidence, oral arguments and examination

Established rules of evidence

Experts normally are appointed and paid by the parties

Judges are drawn from senior practising lawyers

30 November 2010 25

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Different Approaches to Procedure

B. Civil Law Procedure

Civil law

The procedure is “inquisitorial”

The judge plays the main role in collecting evidence

No pre-trial discovery and parties are only obliged to produce those documents

upon which they rely

Civil law trials are primarily based on written evidence and argument

In arbitration practice, there are alternative means to determining the case, beyond

strict legal rights / obligations (e.g. amiable compositeur / ex aequo et bono)

The courts typically appoint experts

Judges are trained and recruited separately from lawyers in private practice

30 November 2010 26

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

III. Different Approaches to Procedure

C. Combining the Two: International Arbitration

International construction contracts normally refer disputes to international

arbitration rather than to national courts

International arbitration is inherently flexible in the procedure to be applied (e.g.

Article 15.1 of the ICC Arbitration Rules)

International procedural guidelines have been formulated which draw upon both

common law and civil law traditions (e.g. the IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence

in International Arbitration)

Composition of the arbitral tribunal will strongly influence the direction that the

arbitration procedure will take

This underlines the importance of selecting the correct tribunal to conduct the

procedure and to determine the case according to the strengths / weakness of your

case (e.g. seeking document discovery; whether substantive issues like good faith

are involved etc.)

30 November 2010 27

Advising on Construction Contracts in Civil Law Jurisdictions

You might also like

- Preliminary References to the Court of Justice of the European Union and Effective Judicial ProtectionFrom EverandPreliminary References to the Court of Justice of the European Union and Effective Judicial ProtectionNo ratings yet

- s11 Introduction To Contract Law PDFDocument32 pagess11 Introduction To Contract Law PDFYusuph kiswagerNo ratings yet

- German Contract LawDocument67 pagesGerman Contract LawVlad Vasile BarbatNo ratings yet

- s11 Introduction To Contract LawDocument32 pagess11 Introduction To Contract LawOmar EljattiouiNo ratings yet

- Validity and Effects of Contracts in The Conflict of Laws (Part 1Document17 pagesValidity and Effects of Contracts in The Conflict of Laws (Part 1JatinNo ratings yet

- Sources: Treaty Law: 1. GeneralDocument14 pagesSources: Treaty Law: 1. GeneralkkkNo ratings yet

- Judicial Cooperation in The European LegDocument8 pagesJudicial Cooperation in The European LegFabíola BatistaNo ratings yet

- SDDocument24 pagesSDTrisha AmorantoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - Licensing and The Patent PropertyDocument39 pagesLecture 6 - Licensing and The Patent PropertyAlonzo McwonaNo ratings yet

- The Eclipse of Private International Law PrincipleDocument22 pagesThe Eclipse of Private International Law PrincipleFernando AmorimNo ratings yet

- The Enforcement of JurisdictionDocument23 pagesThe Enforcement of JurisdictionFernando AmorimNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Exam Notes (Edited)Document67 pagesArbitration Exam Notes (Edited)timNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Reinsurance Law - 1st Edition, 2007 Chapter 9 Jurisdiction and Applicable LawDocument16 pagesA Guide To Reinsurance Law - 1st Edition, 2007 Chapter 9 Jurisdiction and Applicable LawDean RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and TechnologyDocument18 pagesResearch Paper Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and TechnologyMuchokiBensonNo ratings yet

- California Class 5-6Document17 pagesCalifornia Class 5-6api-3791197No ratings yet

- PIL Midterm ReviewerDocument7 pagesPIL Midterm ReviewerAnonymous 6suAq5rWENo ratings yet

- Module 1 - Introduction To Conflict of LawsDocument15 pagesModule 1 - Introduction To Conflict of LawsSheila ConsulNo ratings yet

- CH 1 Contrat PDFDocument33 pagesCH 1 Contrat PDFDarkyyyNo ratings yet

- International LawDocument12 pagesInternational Lawsamlet3No ratings yet

- Topic 2 2018Document17 pagesTopic 2 2018amandaNo ratings yet

- Chapter II, Applicable Law, The FIDIC Red Book Contract, SeppalaDocument57 pagesChapter II, Applicable Law, The FIDIC Red Book Contract, SeppalaDana MardelliNo ratings yet

- 4243 Separabi UpdatedDocument16 pages4243 Separabi UpdatedadityatnnlsNo ratings yet

- CES by Amandeep DrallDocument9 pagesCES by Amandeep DrallAman SinghNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10: Third Party Non-Signatories in English Arbitration LawDocument13 pagesChapter 10: Third Party Non-Signatories in English Arbitration LawBugMyNutsNo ratings yet

- Treaty As Source of International LawDocument20 pagesTreaty As Source of International LawANKIT KUMAR SONKERNo ratings yet

- Business Law - Part II Contract Law PDFDocument42 pagesBusiness Law - Part II Contract Law PDFGregNo ratings yet

- A Basic Introduction To The Sources of International Law: Ori PomsonDocument12 pagesA Basic Introduction To The Sources of International Law: Ori PomsonnheneNo ratings yet

- ICP ADR in Construction IndonesiaDocument23 pagesICP ADR in Construction IndonesiaToni TanNo ratings yet

- M Difference Beween Civil and Common LawDocument56 pagesM Difference Beween Civil and Common LawMukul ChopdaNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws NotesDocument92 pagesConflict of Laws NotesHezzy Okello100% (1)

- EventuallyAdoptedSummaryofCoopRoundtableRC ST CP 1 ENGDocument8 pagesEventuallyAdoptedSummaryofCoopRoundtableRC ST CP 1 ENGJohn MadillNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Partiesto International Arbitration (Gary Born)Document93 pagesChapter 10 Partiesto International Arbitration (Gary Born)Nickoll Bedoya ArandaNo ratings yet

- Unification of Private International Law: (Type The Company Name)Document27 pagesUnification of Private International Law: (Type The Company Name)AmanKumarNo ratings yet

- BORN, Gary. Chapter 10 Parties To International ArbitrationDocument87 pagesBORN, Gary. Chapter 10 Parties To International ArbitrationGabrielNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1334266 PDFDocument17 pagesSSRN Id1334266 PDFKhid AedNo ratings yet

- The Validity of The Arbitration Agreement in International Commercial ArbitrationDocument95 pagesThe Validity of The Arbitration Agreement in International Commercial ArbitrationKASHISH AGARWALNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws LessonDocument6 pagesConflict of Laws LessonQuennie Jane SaplagioNo ratings yet

- ITL ProjectDocument15 pagesITL ProjectJohn SimteNo ratings yet

- Legalese and Legal SystemDocument6 pagesLegalese and Legal SystemHải YếnNo ratings yet

- General Aspects of IelDocument87 pagesGeneral Aspects of IelAaron WuNo ratings yet

- 229 - Sawtell - Causation in English LawDocument30 pages229 - Sawtell - Causation in English LawMichael McDaidNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 The Sources of International LawDocument32 pagesUnit 2 The Sources of International LawChristine Mwambwa-BandaNo ratings yet

- Brownlie - The Peaceful Settlement of International DisputesDocument17 pagesBrownlie - The Peaceful Settlement of International DisputesJosé Pacheco de FreitasNo ratings yet

- General Principles of Law Giorgio Gaja 2Document13 pagesGeneral Principles of Law Giorgio Gaja 2Amartya MishraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19 Choice of Substantive Law in International ArbitrationDocument115 pagesChapter 19 Choice of Substantive Law in International ArbitrationSpeaker 2T-18No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - ASA Special Series No 37 - C MullerDocument24 pagesChapter 4 - ASA Special Series No 37 - C MullerSOUJANYA RAMASWAMYNo ratings yet

- Unification of Private International LawDocument27 pagesUnification of Private International LawpermanikaNo ratings yet

- Principles of International Law: A Brief GuideDocument11 pagesPrinciples of International Law: A Brief GuideElakkiyaNo ratings yet

- International Public Contracts: Applicable Law and Dispute ResolutionDocument58 pagesInternational Public Contracts: Applicable Law and Dispute Resolutionm_3samNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws PDFDocument92 pagesConflict of Laws PDFArhum KhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 Int LawDocument29 pagesChapter 16 Int Lawmarta vaquerNo ratings yet

- Statury InterpretationDocument8 pagesStatury InterpretationJunx LimNo ratings yet

- BENNEL - The Law Governing InternationalDocument27 pagesBENNEL - The Law Governing InternationalRicardo Bruno BoffNo ratings yet

- Article Ohlrogge Saydelles 1644772563Document26 pagesArticle Ohlrogge Saydelles 1644772563Juliana UngefehrNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Court of South AfricaDocument5 pagesConstitutional Court of South Africakenneth.borterNo ratings yet

- Treaties by Malgosia FitzmauriceDocument31 pagesTreaties by Malgosia FitzmauriceEllen BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- The American Law of General JurisdictionDocument31 pagesThe American Law of General JurisdictioniKraniumNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of International LawDocument8 pagesEncyclopedia of International LawSYLVINN SIMJO 1950536No ratings yet

- International Law Summary - Chapter 2Document5 pagesInternational Law Summary - Chapter 2Giorgio Vailati FacchiniNo ratings yet

- Management of Variations Construction Claims Jim Zack Complete PDFDocument294 pagesManagement of Variations Construction Claims Jim Zack Complete PDFDEEPAK100% (1)

- Managing Contract Risks - Importance of Contracts As A Risk Management ToolDocument16 pagesManaging Contract Risks - Importance of Contracts As A Risk Management Toolpoula mamdouhNo ratings yet

- Paul Nation - 4000 Essential English Words 2 - 2009 PDFDocument196 pagesPaul Nation - 4000 Essential English Words 2 - 2009 PDFcivilityssNo ratings yet

- 4000 Essential English Words 3Document195 pages4000 Essential English Words 3jupiter805392% (25)

- Contractor's Perspective (Khawaja)Document2 pagesContractor's Perspective (Khawaja)poula mamdouhNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To The International Arbitration InstitutionsDocument13 pagesAn Introduction To The International Arbitration Institutionspoula mamdouhNo ratings yet

- Construction Issues (Witcombe)Document16 pagesConstruction Issues (Witcombe)poula mamdouhNo ratings yet

- Construction Issues in OmanDocument4 pagesConstruction Issues in Omanpoula mamdouhNo ratings yet

- Construction Issues in OmanDocument4 pagesConstruction Issues in Omanpoula mamdouhNo ratings yet

- Guam War Claims Review Commission ReportDocument86 pagesGuam War Claims Review Commission ReportPoblete Tamargo LLPNo ratings yet

- Death ClaimDocument3 pagesDeath ClaimveercasanovaNo ratings yet

- Seminar 6 - Directors Duty of CareDocument32 pagesSeminar 6 - Directors Duty of Care靳雪娇No ratings yet

- Security Council - Background GuideDocument33 pagesSecurity Council - Background GuideRomeMUN2013No ratings yet

- Adel: Midterms Challenges Upon One'S Candidacy 25 PTS Ground 2: Petition To Declare Nuisance CandidatesDocument10 pagesAdel: Midterms Challenges Upon One'S Candidacy 25 PTS Ground 2: Petition To Declare Nuisance CandidatesJoesil Dianne0% (1)

- Law of Contracts II Lecture Notes 1 13Document56 pagesLaw of Contracts II Lecture Notes 1 13Mohit MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Cpcu 552 TocDocument3 pagesCpcu 552 Tocshanmuga89No ratings yet

- 1 EY-Asia-Pacific-Fraud-Survey PDFDocument28 pages1 EY-Asia-Pacific-Fraud-Survey PDFTania FlorentinaNo ratings yet

- Hinzo 1983 ComplaintDocument31 pagesHinzo 1983 ComplaintjustinhorwathNo ratings yet

- Course OutlineDocument7 pagesCourse OutlineDesmondNo ratings yet

- Arcona, Inc., v. Pharmacy Beauty - 9th Cir. OpinionDocument14 pagesArcona, Inc., v. Pharmacy Beauty - 9th Cir. OpinionThe Fashion LawNo ratings yet

- Structural Prevention (Peace)Document16 pagesStructural Prevention (Peace)geronsky06No ratings yet

- Uy Tong vs. Silva, 132 SCRA 448Document2 pagesUy Tong vs. Silva, 132 SCRA 448Joshua AmistosoNo ratings yet

- QP - Class X - Social Science - Mid-Term - Assessment - 2021 - 22 - Oct - 21Document7 pagesQP - Class X - Social Science - Mid-Term - Assessment - 2021 - 22 - Oct - 21Ashish GambhirNo ratings yet

- 14 FVC Labor Union-PTGWO V Samahang Nagkakaisang Manggagawa Sa FVC-SIGLODocument13 pages14 FVC Labor Union-PTGWO V Samahang Nagkakaisang Manggagawa Sa FVC-SIGLOKorin Aldecoa0% (1)

- Socio-Economic & Political Problems (CSS - PCS.PMS)Document4 pagesSocio-Economic & Political Problems (CSS - PCS.PMS)Goharz2100% (2)

- 2016-2017 Statcon Final SyllabusDocument18 pages2016-2017 Statcon Final SyllabusTelle MarieNo ratings yet

- Tertangkap Tangan Perkara Tindak Pidana Korupsi Dalam Perspektif Nilai Kepastian HukumDocument20 pagesTertangkap Tangan Perkara Tindak Pidana Korupsi Dalam Perspektif Nilai Kepastian HukumHendij O. TololiuNo ratings yet

- The Prosecutor VDocument4 pagesThe Prosecutor VGeeanNo ratings yet

- UCPB v. BelusoDocument4 pagesUCPB v. BelusotemporiariNo ratings yet

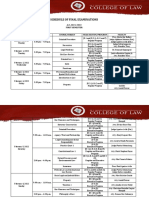

- 1st Sem 2021 22 Finals ScheduleDocument5 pages1st Sem 2021 22 Finals ScheduleRyan ChristianNo ratings yet

- YOGESH JAIN V SUMESH CHADHADocument7 pagesYOGESH JAIN V SUMESH CHADHASubrat TripathiNo ratings yet

- JurisprudenceDocument45 pagesJurisprudenceNagendra Muniyappa83% (18)

- 4515512273482Document1 page4515512273482VermaNo ratings yet

- Constitution AnnotationDocument2 pagesConstitution AnnotationGay TonyNo ratings yet

- Fossum V FernandezDocument7 pagesFossum V FernandezcelestialfishNo ratings yet

- General Exceptions To IPCDocument14 pagesGeneral Exceptions To IPCNidhi SinghNo ratings yet

- Tulabing V MST MarineDocument3 pagesTulabing V MST MarineHencel GumabayNo ratings yet

- Defective Real Estate Documents: What Are The ConsequencesDocument67 pagesDefective Real Estate Documents: What Are The ConsequencesForeclosure Fraud100% (7)

- Contracts - Chapter 2 (Section 3)Document2 pagesContracts - Chapter 2 (Section 3)Leinard AgcaoiliNo ratings yet