Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wiley Financial Management Association International

Uploaded by

Tharindu PereraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wiley Financial Management Association International

Uploaded by

Tharindu PereraCopyright:

Available Formats

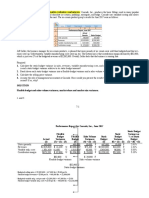

Managing Financial Distress and Valuing Distressed Securities: A Survey and a Research

Agenda

Author(s): Kose John

Source: Financial Management, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Autumn, 1993), pp. 60-78

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Financial Management Association International

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3665928 .

Accessed: 13/06/2014 15:09

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and Financial Management Association International are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Financial Management.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Financial Distress Special Issue

Managing Financial Distress

and Valuing Distressed Securities:

A Survey and a Research Agenda

Kose John,Special Issue Editor

Kose John is Charles WilliamGerstenbergProfessorof Bankingand Finance

at the SternSchool of Business,New YorkUniversity,New York,New York.

0 The role of high leveragein corporaterestructuringand in understandinghow firmsdeal with financialdistress.A

the popularityof junk bonds (original-issue, high-yield very active academic literaturehas developed in recent

bonds) have been importantaspects of the corporatefi- years on variousaspects of dealing with financialdistress

nance scene in the 1980s. As more and more firms have and the privateand court-supervisedmechanisms of re-

defaulted on their debt and filed for bankruptcyin the solving default.At the same time, investorshave become

recent recession, financial economists, financial manag- increasinglyconcernedaboutdefaultriskand valuationof

distressed securities incorporatingthe institutionalreali-

ers, andlegal scholarshavebecome increasinglyinterested

ties of troubled debt restructuring.The purpose of this

special issue is to showcasenew empiricaland theoretical

I wish to thank Teresa A. John for permission to draw from earlier

researchon these topics, i.e., managingfinancialdistress

collaborativework on financial distress. I am also grateful to several

and valuing corporatesecuritiesincorporatingpayouts in

colleagues and friendsand otherresearcherswho reviewedmanuscripts

for the special issue andprovidededitorialadvice, especially Ed Altman, troubledreorganizations.While the literatureon the first

Mitch Berlin, Steve Brown, Allan Eberhart, Stuart Gilson, Edie topic, broadly defined, has become quite extensive in

Hotchkiss, Ed Kane, Ron Masulis, Jeff Netter,Tony Saunders,Lemma recentyears,the literatureon the second topic is still in its

Senbet, Bruce Tuckman,Gopala Vasudevan,and KarenWruck. I also

infancy.New researchon these topics is presentedin the

acknowledgehelpful discussions with them on the topics of this survey.

I am immenselygratefulto JamesAng, the Editorof FinancialManage-

nine papersthat appearin this special issue.

ment for enormousencouragement,supportand guidanceon all aspects The purposeof this surveyarticle is to summarizeand

of this special issue. synthesize the recent research in the areas of financial

60

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOHN/ MANAGING

FINANCIAL

DISTRESS 61

distress, asset and debt restructuring,bankruptcyand val- examples of hardcontracts.Commonstock and preferred

uationof distressedsecurities.1The new researchfeatured stock are examplesof soft contracts.Here, even thoughits

in this special issue is also surveyedhere. Additionally,I claimholdershave expectationsof receiving currentpay-

present an agenda for future research in the areas of outs fromthe firmin additionto theirownershiprights,the

financial distress, design of contractsand proceduresto level and frequency of these payouts are often policy

deal with it, and techniquesfor the valuationof corporate decisions made by the firm.2These payouts can be sus-

securities and contractsincorporatingstrategiesand out- pendedand/orpostponedbasedon the availabilityof liquid

comes induced by the legal system governing breach of resourcesremainingin the firm aftersatisfying the claims

contractualpromises. of the hardcontracts.

The rest of the paperis organizedas follows. In Section The assets of a firm also have a naturalcategorization

I, a simple conceptualframeworkfor managingfinancial based on liquidity.Cash or cash-like (marketable)securi-

distressis presentedwhich providesa scheme for organiz- ties areliquidassets.Long-terminvestments(suchas plant

ing the survey. Theoretical work and recent empirical and machinery)which may only produceliquid assets in

evidence on asset restructuringis summarizedin Section the futuremay be called "hard"assets.

II. Recent theory and evidence on privatedebt restructur- The above categorizationsof the financingcontractsof

ing (debtworkouts)is collected in Section III.Theoretical a firm and its assets give rise to a naturaldefinition of

andempiricalworkon the formalbankruptcy(Chapter11)

financial distress.A firm is in financialdistressat a given

processis reviewedin SectionIV.Efficiencyaspectsof the point in time when the liquid assets of the firm are not

currentU.S. bankruptcyprocedure,the design of an opti- sufficient to meet the currentrequirementsof its hard

mal procedureand proposals for bankruptcyreform are

contracts.Since financialdistressresultsfrom a mismatch

discussed there. In Section V, the valuationof corporate

between the currentlyavailableliquid assets and the cur-

securities and contractswith significant probabilitiesof

rent obligationsof its "hard"'financialcontracts,mecha-

default (triggeringrenegotiationand legal resolution) is

nisms for managingfinancialdistressrectifythe mismatch

discussed. Each of these sections includes a brief survey

of relevantexisting literature,an overview of the papersin by either restructuringthe assets or restructuringthe fi-

this special issue which fall in thatarea,and some sugges- nancing contracts,or both.

On the asset side, the hard assets can be wholly or

tions for futureresearch.Section VI containsan agendafor

furtherresearchand concludingremarks. partiallyliquidatedto generateadditionalliquid assets to

meet the currentobligations.However,prematureliquida-

tion of illiquid assets results in the destructionof going-

I.ManagingFinancialDistress: A Model concernvalue and involves the cost of liquidation.If this

The financing contractsof a firm can be loosely cate- avenueis pursuedto deal with financialdistress,the value

gorized into hardand soft contracts.An exampleof a hard lost due to prematureliquidationof assets representsthe

contractis a coupondebtcontractwhich specifies periodic cost of managingfinancialdistress.

paymentsby the firmto the bondholders.If thesepayments Anotherset of mechanismsto deal with financial dis-

are not made on time, the firm is considered to be in tress involves restructuringthe financial contracts. One

violation of the contractand the claimholdershave speci- mechanismis to negotiate with the creditorsand restruc-

fied and unspecifiedlegal recourseto enforcethe contract. ture the terms of the hard contractssuch that the current

Contracts with suppliers and employees may be other obligation is either reducedto an amountwhich is closer

to the cash currentlygeneratedby assets, or deferredto a

'The literatureon financial distress, asset and debt restructuring,and later date. Anothermechanismis to replace the hardcon-

bankruptcyhas now become very extensive and I do not intendthis to be tract with soft securities with residual ratherthan fixed

an exhaustivesurveyof it. See JohnandJohn[70] and SenbetandSeward

[102] for other recent surveys. Wruck [116] also surveys in detail a

selected subset of empirical papers in the area. The area of financial 2Evenequitycontractsassociatedwith certainorganizationalformsmay

distress and resolutionmechanismsis closely relatedto that of optimal have mandatorypayoutrequirementsmakingit "harder"thanthose in the

design of contractsand securities, and to that of capital structure.The corporateform. For example, a real estate investmenttrust(REIT)must

Summer1993 issue of FinancialManagementfeaturesa special issue on distributeat least 95% (90% prior to 1980) of its net annual taxable

"SecurityDesign"editedby FranklinAllen. Forsurveyson thetheoretical income, excluding capitalgains and certainnoncashtaxable income, to

literatureon optimal securitydesign, see Allen [4], Allen and Gale [5], shareholders.Damodaran,John,andLiu [37] studychanges in organiza-

Allen and Winton[6], and HarrisandRaviv [57]. Foran excellent survey tional forms and document that financial distress and choice over the

of the modem literatureon capital structure,see Harrisand Raviv [58]. restrictivenessof the associatedequity contractare majordeterminants.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

62 FINANCIAL / AUTUMN1993

MANAGEMENT

payoffs. In general, debt restructuringinvolves replacing defaults.As we discussed above, suboptimalliquidations

an existing debt contract by a new contract with (i) a can occur also following liquidity-induceddefaults.Debt

reductionin the requiredinterestor principalpayments, restructuringmay be a solution. Mechanismswhich facil-

(ii) extension of maturity,or (iii) placement of equity itate debt restructuring(privateor court-supervised)will

securities (common stock or securities convertible into reducethe costs of prematureliquidationfollowing liquid-

common stock) with creditors.Under the new contract, ity defaults. However, the same mechanismswill reduce

thereis less financialdistress. inefficiencies following a strategic default, encouraging

A thirdmode of financialrestructuringis to raise addi- such defaults. The ex ante efficiency of the debt restruc-

tional currentliquidity by issuing new financial claims turingmechanismswill dependon the relativeimportance

of these two effects. HartandMoore [60], HarrisandRaviv

against future cash flows generatedby the assets, which

may avoid or reduceprematureliquidationof these assets. [59], and Bolton and Scharfstein [28] develop related

Here, even though the original hard contract was left arguments.

unaltered,the structureof financingclaims was alteredby In additionto incompletecontracting,asymmetricin-

thenew financingundertaken.Whenthe new claims issued formationbetween debtorsand creditorsabout the value

have a softercontractor longermaturity,the new package of the assets (ongoing firmvalue or liquidationvalue) can

of financingclaims are less onerouson the firm,resolving frustratemutuallybeneficialdebt renegotiation(see, e.g.,

financialdistress. Giammarino[52]). As Brown [30] points out, when there

It should be pointed out that both asset restructurings is symmetricinformationbetweenmanagementandcred-

and debt restructuringscan be accomplishedprivatelyor itors, a privateworkoutis always successful. Many of the

theoreticalmodels in the area examine the consequences

througha formalcourt-adjudicated process.Exactlywhich

method is implementedto reorganizea financially dis- of incompletecontractingandasymmetricinformationon

the efficiency of contractingand the mechanismsto man-

tressed firm depends on the relativecosts and benefits of

each mechanism.In a scenariowith completecontracting, age financialdistress arisingfrom breachof the termsof

the contract.

i.e., a complete state-contingentset of contracts are al-

lowed by the legal system, an initialdesign of contractcan I will use the framework developed above to next

be madesuchthattherequiredfinancingcanbe undertaken organize the survey of the theory and evidence on asset

avoiding any prematureliquidation of assets. In other restructuring(Section II), privatedebt restructuring(Sec-

tion III) and the formalbankruptcyprocess (Section IV).

words, the choice of initial contract would precludede-

faults of the type discussed above due to shortages of

liquidity, or it will be renegotiatedto avoid suboptimal

liquidations. However, in practice, the admissible con-

II.Asset Restructuring

tractsare incomplete.Often,outside investorsor the court As outlined in the general frameworkdeveloped in

system do not have the detailed informationrequiredto Section I, one set of mechanisms to deal with financial

enforce many contracts. For example, the currentcash distressinvolvesrestructuringthe asset side of the balance

availablemay not be observableto these outside parties, sheet to generatesufficientcash to meet the requirements

which would make contracts specifically contingent on of the hardcontracts.Assets can be sold (eitherpiecemeal

thesecash flows hardto enforce.Managersmayhave some or in their entirety) to other firms or new management

scope to divertsome of the cash flows to managerialperks teams. Asset sales can be accomplished privately or

on their favorite (but unprofitable)projects, etc. In the throughcourt-supervisedstages either duringbankruptcy

extreme, if managerscan appropriateall the cash flows, reorganization(Chapter 11 of the BankruptcyCode) or

then the managerswould always choose to defaultstrate- underthe liquidationprocess(Chapter7 of the Bankruptcy

gically anddivertthe cash to themselves.Of course, cred- Code). Each of these alternativeshas differentcosts at-

itors would anticipatethis andrefuse to lend. As Hartand tached to them. Whether asset restructuringis actually

Moore [60] argue, one possible resolution is to give the usedto managefinancialdistresswoulddependon its costs

creditors, following nonpayment (default), the right to relativeto those of financialrestructuring.3

liquidateassets andappropriatethe proceedsfromliquida-

tion within limits specified by the contract.Since liquida- 3Therole of asset restructuringin improvinginvestmentincentiveswhen

tion of assets results in loss of future cash flows to the risky debt is outstandinghas been analyzedby John [761 and John and

managers,the threatof liquidationwould deter strategic John[77]. John[76] providesa theoreticalrationalefor value gains from

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOHN/ MANAGING

FINANCIAL

DISTRESS 63

Shleifer and Vishny [104] study the liquidity costs John and Vasudevan[74] obtain severalempiricalim-

associatedwith interfirmasset sales promptedby financial plications:

distress.4In identifyingthe determinantsof marketliquid- (i) Successful completion of debt workouts should

ity, they focus on (i) fungibility(i.e., the numberof distinct resultin increasedstock pricesandincreasedcom-

uses and users for a particularasset), (ii) participation bined firm value. Chapter 11 filings should pro-

restrictions(e.g., regulationson foreign acquisitions,anti- duce a negativeannouncementeffect. Firmswhich

trustrestrictions),and (iii) creditconstraintsin the indus- privatelyrestructuretheirdebt have higher going-

try.They arguethatthe pricereceivedin a distresssale may concern value when comparedto firms which file

have large liquiditydiscounts if the entireindustryis in a for Chapter 11. Average time spent by firms in

downturn.In an illiquid secondary market,the costs of Chapter 11 reorganizationsis more than that in

asset restructuringare likely to be high, and financial workouts(Gilson, John, and Lang [55] document

restructuringmay provide the dominant mechanisms of evidence consistentwith these predictions).

dealing with financialdistress. (ii) Asset sales by distressedfirms to make debt pay-

In an integratedmodel of asset and debt restructuring, ments have a positive effect on stock prices. This

John and Vasudevan[74] examine how the cost of asset is consistentwith the empiricalevidence in Lang,

sales, the currentliquidity position of the firm, and the Poulsen, and Stulz [87].

option value of its equity determinethe choice between a

(iii) Deviations from absolute priority are higher in

private workout (with or without some asset sales) and workoutsthan that in Chapter11 reorganization.

filing for the formalChapter11 process, possibly seeking Write-downsarelower in workouts.This is consis-

debtor-in-possession(DIP) financing. Since asset sales tent with Franksand Torous[48].

may extinguish some of the option value of equity, there

is an endogenous cost of asset sales to equityholders(in (iv) Write-downs in prepackagedbankruptcyfilings

additionto the costs of illiquiditydiscussedby Shleiferand will be lowerthanordinaryChapter11 reorganiza-

Vishny [104]). When the combinedcosts of asset liquida- tion.

tions arehigh, the firmmay file for Chapter11 bankruptcy (v) The payoffs to bondholdersmonotonicallyincrease

and seek new financingas DIP financingwhich has prior- in the indirectcosts of bankruptcy.

ity over existing debt. To determinethe expected payoffs The frameworkof Section I, in characterizingfinancial

to equity underthe differentalternatives,the reorganiza-

distress as a mismatch between the currently available

tion process itself (both workouts and Chapter 11) is

liquid assets and the current obligations of its "hard"

modelled as an alternatingoffer bargaininggame with financialcontracts,suggeststhatafterfinancialdistresshas

asymmetricinformation,where the equityholdersare bet- occurred,managingit involvescorrectingthe mismatchby

ter informedthanthe bondholdersor thejudge (in Chapter either increasingthe liquidityof the assets (throughasset

11). Based on the allocation of value in equilibrium,the sales) or decreasingthe "hardness"of the debt contracts

outcomes include privaterestructuringwith and without

(throughdebt renegotiation).However,before the firm is

asset sales, andChapter11 filings with DIP financing.The in financialdistressit can design the structureandthe form

time spentin the Chapter11 reorganizationis endogenous of its debt contractsand choose its leverage and liquidity

to the model and one of the possible outcomes is a "pre- policies suchthatits costs of financialdistressarereduced.

packaged"bankruptcywith a speedy reorganization. Opler [97] andJohn [75] study these issues empiricallyin

theircontributionsin this special issue. Leveragedbuyouts

have been increasinglyfunded in ways which appearto

spin-offs and asset sales and characterizesthe optimal allocation of the reduce the risk and cost of financial distress. Leveraged

pre-spin-off debt. John and John [77] demonstrateconditions for the

optimalityof limited recourseprojectfinancingarrangements.

buyout financing methods include the use of specialist

4Asset sales in bankruptcymay have some advantagesover those done sponsors, strip financing, covenants which require that

privatelyoutsideformalbankruptcyproceedings.Purchasingassets from excess cash flows be paid to debtholdersand debt provis-

a financiallydistressedfirmis less riskyin Chapter11 becauseasset sales ions which allow deferralof interestpaymentsin periods

are executed by a court orderand are thus free from legal challenge. In of financialdistress.Opler [97] documentsthe prevalence

addition, if the seller subsequentlyfiles for Chapter11, the buyer may

have to returnthe assets as "avoidablepreference"or "fraudulenttrans-

of these innovative financing techniques and estimates

fer."Giventhe materialcosts of beingchallengedor cancelled,asset sales their impacton the risk-adjustedcost of debt in 63 LBOs

in Chapter11 may be preferredby potentialbuyers. which occurredin 1987 and 1988. The results show that

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

64 FINANCIAL / AUTUMN1993

MANAGEMENT

sponsorshipby an LBO specialist lowers the weighted restructuringby firms in distress.All of the above papers

averagecost of LBO debt and the imputedcost of capital document that asset sales are frequentlyused by finan-

by roughly 60 basis points. In addition, debt provisions cially distressedfirmsin theirsample.Brown,James,and

which allow deferralof interestpaymentson junior debt Mooradian[3 1] find thatfirmswhich sell assets aredistin-

and which maintaina minimum bond value are used in guishedby multipledivision or multiplesubsidiaryopera-

many of the LBOs in the sample. While these provisions tions.Conversely,most of thefirmswhichdo not sell assets

do not lower financingcosts, theiruse indicatesthatLBO operate only a single division. They also find that the

capital structuresare designed to avoid the need for debt announcementof asset sales elicits insignificantabnormal

workoutsor Chapter11 proceedingsin periodsof financial stock returns.However,the announcementeffect is posi-

distress. tive for the subsetof seller firms which also subsequently

Given the above characterizationof financial distress, avoidbankruptcy.Lang,Poulsen,andStulz [87] document

a firm with high costs of financialdistress will reduce its that the abnormalreturnis higher for sellers who use the

exposure in two ways: (i) increase the liquid component proceedsfrom asset sales for retiringdebt. Asquith,Gert-

of its assets, and (ii) reducethe extent of its hardcontracts ner, and Scharfstein[15] conclude that asset sales are an

(such as debt). Based on this argument,John [75] postu- importantmeans of avoiding bankruptcy.They find that

lates (i) a positive relationshipbetweencorporateliquidity only threeout of 21 companiesthatsell over 20% of their

assets go bankrupt.

and distresscosts, and (ii) a negativerelationshipbetween

The overall evidence seems to suggest that although

leverageanddistresscosts.5A majorcomponentof distress

asset sales are used to deal with financialdistress,in most

costs is the costs of illiquidityof assets.Thesecosts include

cases they are used in conjunctionwith debtrestructuring.

costs of distressed asset sales and loss of going-concern

value in liquidations.Some new proxies are proposedfor

the costs of illiquidity and the indirectcosts of financial III.PrivateDebt Restructuring

distress. These include Tobin's q, R&D and advertising Informal reorganizationof corporatefinancial struc-

expenditures,an index of asset specificity and an index of turesthroughdebtrestructuringsandprivateworkoutscan

the probabilityof bankruptcy.The liquidityratio is docu- be used to "soften"the hardcontractswhich caused finan-

mentedto be positivelyrelatedto these proxiesof financial cial distress. Consistent with the model of Section I, to

distresscosts. It is negatively relatedto proxies for alter-

remedy financial distress the firm will reduce or defer

nate sources of anticipatedliquidity such as intermediate

payments on its debt contractsor replace debt with soft

cash flows, debt financing, length of cash cycle and the securitieshavingresidualratherthanfixedpayoffs.Wecan

collateral value of assets. Total debt is also negatively define a debt restructuringas a transactionin which an

relatedto Tobin's q and asset specificity as well as mea- existing debt contractis replacedby a new contractwith

sures of intermediatecash flows. Long-termdebt is also (i) a reductionin the requiredinterest or principalpay-

negativelyrelatedto proxies for alternatesourcesof antic- ments, (ii) extension of maturity,or (iii) placement of

ipated liquidity such as intermediatecash flows, debt equity securities(common stock or securitiesconvertible

financing,length of cash cycle and the collateralvalue of into common stock)with creditors.Privatedebtrestructur-

assets.Totaldebt is also negativelyrelatedto Tobin'sq and ing is surveyedin this section, and debt reorganizationin

asset specificity as well as measuresof intermediatecash a court-adjudicated formalbankruptcyprocessis surveyed

flows. Long-termdebt is also negativelyrelatedto Tobin's in Section IV.

q and asset specificity. Overall, the evidence is strongly Haugenand Senbet [61], [62] arguethatcapitalmarket

consistent with the hypothesized relationshipsbetween mechanismscould accomplishthe restructuringof prob-

corporateliquidityand financialdistresscosts, andcorpo- lematic hard contractsand replacing them with a softer

rate leverageand financialdistresscosts. mix. They arguethat the transactionscosts of these "pri-

Brown, James, and Mooradian[31], Asquith,Gertner, vate" mechanisms are small and should form an upper

and Scharfstein [15], Lang, Poulsen, and Stulz [87], bound on the costs of managingfinancialdistress.Jensen

Hotchkiss [64], and Ofek [96] presentevidence of asset [67], [68] has also arguedthat since these privaterestruc-

turingsrepresentan alternativeto formalbankruptcypro-

5Thenegativerelationshipbetween leverageand distresscosts has been

ceedings, it pays to "privatize"bankruptcyif this informal

documentedin severalearlierstudies,e.g., TitmanandWessels[105]. See mechanism is cost-efficient. Roe [100] has also made

John[75] for a summaryof this researchanda completelist of references. similarargumentsin the legal literature.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FINANCIAL

JOHN/ MANAGING DISTRESS 65

A simpleconceptualframeworkis developedin Gilson, In these cases, the tenderingbondholdersarealso askedto

John, and Lang [55] to determine the choice between vote to change or eliminate the existing debt covenants.

private restructuring and formal bankruptcy process, The acceptanceof the exchangeddebt is madeconditional

which is based on two factors.Let AC be the cost saving on approvalof the consent solicitation by the required

by choosing the first alternativeover the second. If AC is majority. In these cases, the consent solicitation is so

positive, by choosing the firstalternative,the firm'sclaims designedthatthe benefitsof nonparticipationareexceeded

can be restructuredto leave each of the originalclaimants by the loss from holding onto the old bonds strippedof

better off (they share the incrementalvalue AC collec- covenants. Kahan and Tuckman [81] and Gertner and

tively). The largeris AC,the strongerarethe claimholders' Scharfstein[50] analyzethe holdoutproblemsin exchange

incentivesto settle privately.However,the privatealterna- offers and consent solicitations.

tive will be adoptedonly if thereis unanimousagreement Gertnerand Scharfstein[50] have predictionsfor the

on how to shareAC. Impedimentsto reachinga settlement effect of workoutsand consent solicitationson the invest-

on a private restructuringcan be (i) holdout problems ment decisions of financiallydistressedfirms. They con-

encounteredwhen a firm's debt is held by a large number cludethatinvestmentincentivesarenot typicallyimproved

of diffuse creditors, (ii) informationalasymmetriesthat by debt workouts.Kahanand Tuckman[81] analyze con-

can arise betweenpoorly informedoutsidecreditorsand a sent solicitations and empirically examine bondholder

better informedmanageror insiders of the firm, and (iii) wealth effects on announcementsof consent solicitations.

conflicts among differentgroupsof creditors. When the bondholdersact atomistically,i.e., on theirown

(without forming coalitions), it is shown that coercive

consent solicitations may be necessary for a successful

A. HoldoutProblem covenant change. The evidence, however, is that bond

Achieving an agreementamongcreditorsoutsideof the prices increaseon announcementof consent solicitations.

formalbankruptcyprocess will dependupon what type of This suggeststhatbondholdersmay collude andact coher-

debt is restructured,e.g., privatedebt or public debt. The ently in the face of coercive consent solicitations.

restructuringof publicdebtis governedby the TrustInden-

ture Act of 1939, which requiresunanimousconsent of

every bondholder to change the maturity,principal or B. InformationalAsymmetry

coupon rate of interestin the bond indenture.Such strin- Often, corporateinsidersand managementknow more

gent votingrulesprecludea debtrestructuringin whichthe aboutthe value of the firm,its assets, its futurecash flows,

core terms of widely held public debt can be changed. etc., than outside investors, including creditors.In such

Consequently,almostall restructuringsof publicdebttake cases, asymmetricinformationexists between corporate

the form of an exchange offer. insidersandcreditors,such thatthe creditorscannotprop-

An exchange offer and the resultingholdout problem erly evaluate the new package of claims proposed in a

can be understoodbased on the frameworkdeveloped in workout.They also believe that the debtor-management

Section I. In an exchange offer,the bondholdersare given may misrepresentthe value of the firm. Giammarino[52]

the option to exchange their old bonds for a package of models such a scenarioand shows that the creditorsmay

new securities(often includingsome form of equity). The actually reject mutually beneficial private restructuring

idea here is to swap the existing "hard"contract for a andchoose, in equilibrium,a court-imposedproposalwith

"softer"mix. Since participationis optional, individual the attendantdeadweightcosts. In other words, informa-

bondholdersmay choose to "hold out"in the expectation tionalasymmetrycan thwartan agreementfor an attractive

that their bonds would be more valuable (in the post- settlement.Brown [30], on the other hand, examines the

exchange, less-distressedfirm) than the new package of choice between privateworkoutsand the bankruptcypro-

securities. Since all bondholdershave similar incentives cess in a symmetricinformationsetting.By modellingthe

(assumingthatthey do not collude), the exchange offer is rules of the court-adjudicatedprocess, Brown [30] shows

likely to fail. The termsof the new packetof securitiesare that the equilibriumalways involves a successful private

often set to coerce participation.Coercive techniquesare workout.

used by corporationsto implement successful exchange John and Vasudevan [74] analyze the firm's choice

offers. Exchange offers are often accompaniedby modifi- between workouts(possibly with asset sales) and Chapter

cation of the covenants of the original bonds through a 11 filing (with subsequent DIP financing) in a setting

techniqueknownas consentsolicitationsor exit covenants. wherethereis asymmetricinformationbetweenthe corpo-

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

66 FINANCIAL

MANAGEMENT

/ AUTUMN1993

rate insiders and the creditors/courts.The details of the The economic reasoning underlyingthese findings is

model andresultsarediscussedin Section II. Gertner[49] suggestedby the model of Section I and the frameworkof

also examinesthe signallingrole of the securitiesissued in Gilson, John, and Lang [55] summarizedearlier in this

distresseddebtrestructurings.6See also MyersandMajluf section. On the asset side, intangibleassets proxy for the

[95]. destructionof going-concernvalue which would occur if

financial restructuringfails and asset restructuringis re-

quired.In fact, Gilson, John,andLang [55] use the differ-

C. Coalitionsand Conflicts ence between marketvalue and the replacementcost of

Fora typicalfirmwith a complex capitalstructurethere assets (scaled by replacementcost) as the proxyvariable.

are severalgroupsof claimants,includingdifferentclasses The value saved (AC) if the firm maintains operating

of debtholders,tradecreditors,stockholders,management,

continuity through a workout is higher, the higher the

etc. Even when the privatereorganizationcosts are less

proportionof intangibleassets. Factors(ii) and (iii) above

thanotheralternatives(leaving a largeraggregatevalue of affect the probabilitythat a settlement is reached in the

assets), its distributionamongthe variousclaimantscould bargainingprocessleadingto a successful workout.Firms

be criticalto a successful debt restructuring.The bargain- with banksas dominantcreditorscan moreeasily renego-

ing issues involvedin modelingthe intergroupconflicts of tiate their debt because banks are more sophisticatedand

interests and coalition formation have been studied in less numerousthan other kinds of creditors,resulting in

Bulow andShoven [34], GertnerandScharfstein[50], Hart fewer holdouts.Similarly,conflicts of interestamong dif-

and Moore [60], John and Vasudevan[74], Harris and ferentclasses of creditorsaremoremanageablethe smaller

Raviv [59], Kaiser [82], Walzer [106], and Bergmanand the numberof distinctcreditorclasses.

Callen [20], [21]. These conflicts of interest can lead to

Gilson, John, and Lang [55] also provide evidence on

distortationsin investment(underinvestment,overinvest- the principaltermsof restructuringthe debt for the firms

ment and excessive continuationor liquidation).Details in their sample. As mentionedearlier,debt restructuring

will be discussed in Section IV.B. on the efficiency of the

involves "softening"the hardcontractby reducinginterest

bankruptcyprocess. or principal payments, extending the debt maturity or

distributingequity securitiesto creditors.In about73% of

D. EmpiricalEvidenceon DebtWorkouts all successful workouts,there is a reductionin promised

Gilson, John, and Lang [55] was the first systematic paymentson the debt. In about74%of successful restruc-

turings,new equitysecuritiesaregiven to creditors.Exten-

empirical study of debt workouts. They investigate the sion of maturityis only observed in 49% of workouts.

incentives of financially distressed firms to restructure

Differentclasses of debt also appearto be restructuredon

theirdebtprivatelyratherthanthroughformalbankruptcy.

substantiallydifferentterms.Approximately49% of bank

They analyze the experienceof 169 publicly tradedcom-

debt restructuringsprovide for an extension of maturity,

panies that experienced severe financial distress during

1978-1987. Eighty of these firms successfully avoided compared with only 6.7% of restructuringsof publicly

tradeddebt;this latterresultis consistentwith firmsoffer-

bankruptcyby restructuringtheirdebt out of courtand 89

ing shorter-maturity debt in exchangeoffers to discourage

firmswereunsuccessfulin workingouttheirdebtprivately

holdouts (see the section on holdouts above). Although

and filed underChapter11 of the U.S. BankruptcyCode.

The studyfinds thatthe asset characteristicsand financial 51.4% of bank debt restructuringsresult in bank lenders

characteristicsjointly determinethe firm'schoice between receivingequityin thefirm,holdersof publiclytradeddebt

are given equity securities 86.7% of the time. The latter

informaland formal reorganizationmechanisms(as sug-

difference is a likely consequence of various legal and

gested in ourmodel of Section I). More specifically,finan-

cial distress is more likely to be resolved throughprivate regulatoryfactors that make it costly for banks to hold

workouts,when (i) a greaterproportionof the firm'sassets large amountsof equity in publicly tradedcompanies.7

are intangible,(ii) a greaterproportionof its debt is bank

debt, and (iii) the firm has fewer lenders (fewer distinct 71Inparticular,banks are constrainedfrom holding significantblocks of

classes of debt outstanding). stock in other firms by Section 16 of the Glass-SteagallAct, the Bank

Holding CompanyAct and the FederalReserve Board's RegulationY.

Temporaryexceptions may be grantedwhen stock is obtainedin a debt

6White[1 15] also studiesthe choice between liquidationversuscontinu- workout.Moreover,banks must divest theirstockholdingsafterapprox-

ation in an asymmetricinformationsetting. imately two years, althoughextensions are possible. Second, creditors

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOHN/ MANAGING DISTRESS

FINANCIAL 67

Gilson, John,and Lang [55] also documentsome mea- sales and capital expenditurereductions are commonly

sures of the relativecosts of workoutsversus Chapter11. used by firmsin financialdistress;(ii) banksrarelyforgive

The average length of time spent by 89 firms in Chapter principalon outstandingloans or providenew financingin

11 is over20 months;the averagelengthof the 80 workouts a workout;and (iii) workout of public debt throughex-

is about 15 months.The differencein costs is significantly change offers is an importantdeterminantof the success

higherin the 30 cases in the Gilson-John-Langsamplethat of the overall workout.

involvedprivaterestructuringof publicly tradeddebt. The Hoshi, Kashyap,and Scharfstein[63] explore the role

average time for exchange offers (which is the common of main-bankrelationshipsin reducingthe costs of finan-

mechanismfor restructuringpublic debt) in the sample is cial distressin Japan.They presentevidence thatJapanese

just under seven months. Gilson, John, and Lang [55] firms in industrialgroups - those with close financial

provide the only availableevidence on the direct costs of relationshipsto their banks, suppliers,and customers-

privateworkouts.The offer-relatedcosts of these exchange invest more and sell more than nongroupfirms. Parallel

offers, on average,is only 0.65% of the book value of the resultsarefound for nongroupfirmswhich do have strong

assets. By contrast,the averagelegal andprofessionalfees ties to main banks.

reportedin the Chapter 11 process range from 2.8% to Gilson [54] documentsthat corporatedefault leads to

7.5% of total assets. Gilson, John, and Lang [55] also significantchanges in the ownershipof firms' equity and

provide indirect evidence of the relative costs of formal the allocationof rights to managecorporateresources.In

and informal reorganizationsusing evidence from stock his sample of 111 firms in financialdistressduring 1979-

returns.To the extent that workoutsare less costly than 1985, banklendersfrequentlybecome majorstockholders

Chapter 11, both shareholdersand creditorsshould gain or appointnew directors.On average,only 46% of incum-

when debtworkoutssucceed.The Gilson-John-Langstudy bent directorsremainwhen bankruptcyor debt restructur-

documents that shareholdersof companies that success-

ing ends. Directors who resign hold significantly fewer

fully worked out their debt realized an average 41% in- seats on otherboardsfollowing theirdeparture.Common-

crease in stock value over the period of workout (i.e., stock ownershipbecomes more concentratedwith large

startingwith announcementof the default),net of general blockholdersand less with corporateinsiders.Gilson [53]

market movements. On the other hand, firms which at- documents changes in top managementfollowing finan-

tempteda workoutbut failed and filed for Chapter11 had cial distress (52% annualturnover)which is significantly

an average cumulative stock return of -40% over the

higher than that for a random sample (12%) and that

restructuringperiod ending with the Chapter11 filing. At categorizedas poorly performingbut not financiallydis-

least partof the 81%differencein these returnsrepresents tressed(19%).

the market'sestimate of relativecost savings between the

Brown, James, and Mooradian[32] examine debt re-

two mechanisms.8Theyalso findthatthemarketis capable

structuringsmade by financially distressed firms under

of predictingthe outcome of the workoutattempt.

asymmetricinformation.Their model of public debt ex-

In subsequentwork, Asquith,Gertner,and Scharfstein

change offers predictsthat firms with unfavorableprivate

[15], Brown, James, and Mooradian[32], and Franksand informationwill offerequityclaimsto convincebondhold-

Torous[48] examinedebtworkoutsfurther.Asquith,Gert-

ers thatthe firm'sprospectsare poor. However,when the

ner, and Scharfstein[15] examine workoutsof 102 firms

private lender is well-informed,offering equity in a re-

which issued junk bonds and then subsequentlyencoun-

tered financial distress. Their findings include: (i) asset structuringconveys favorableprivateinformationto out-

siders. Consistent with their analysis, they find positive

averageabnormalreturnsaroundthe reorganizationsthat

offer equity to privatelenders and senior debt to public

can be held legally liable to other claimholdersif the firm's financial

conditiondeterioratessubsequentto theirassuminga controllinginterest

debtholders. In contrast, they find significant negative

in the firm and exercising"undueinfluence"over its business(Douglas- averageabnormalreturnswhen privatelendersareoffered

Hamilton [41]). For recent analyses of the optimalityof banks holding senior debt and public lenders are offered equity. Franks

equity in borrowingfirms, see Berlin,John,and Saunders[24] andJohn, and Torous[48] examinemanyaspectsof workoutswhich

John, and Saunders[79]. See also Johnand John [71].

were examinedin Gilson, John, and Lang [55]. They also

8A fraction of this 81% difference may also representemerging new

find that(i) less liquid andless solvent firmsenterChapter

information,i.e., the firmsultimatelyfiling Chapter11 aresystematically

less profitableafter attemptsat restructuringbegan. Such information 11 andthat,consequently,write-downsof creditors'claims

may come out graduallyover the restructuringperiod. are larger in Chapter 11 comparedto workouts,and (ii)

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68 FINANCIAL / AUTUMN1993

MANAGEMENT

deviations from the rules of strict absolute priorityrule in the contractexplicitly.However,the bankruptcyproce-

(APR) are largerin workouts.9 dures are implicitlya partof every contractand affect the

allocationof resourcesjust like the financialcontracts.For

IV.The Chapter 11 Process example, formal bankruptcyproceduresestablish the al-

ternativeto a privateworkoutsettlementandhence affect

An alternativemechanism for dealing with financial

the natureof such settlements(see John and Vasudevan

distressis the formal,court-supervisedbankruptcyprocess

[74] and Gilson, John, and Lang [55]). Bankruptcyrules

(of financialrestructuring)governedby Chapter11 of the

U.S. BankruptcyCode. Although in the previous section may affect investmentpolicy, extent of liquidation and

we highlightedthe relatively lower direct costs of work- operating decisions through their effects on bargaining

outs comparedto bankruptcy,the formalprocesshas bene- outcomes. The availability of funds for investment,the

fits as well as costs. Some of the benefits are as follows: capital structuresandthe type of investmentschosen may

all be influenced by bankruptcy rules. Therefore,

(i) The automatic stay provision of the Bankruptcy

Code protects the firm from creditorharassment designing efficient bankruptcyproceduresis important.

A largebody of researchon the efficiency of the bank-

while it reorganizes.

ruptcy process focuses on its effects on the investment

(ii) The less restrictivevoting rulesin Chapter11 make

policy of the firm. Two types of investmentdistortions

it easier to get a reorganizationplan accepted.

arisewhenthe firmis in financialdistress.Whenriskydebt

(iii) The BankruptcyCode allows the firm to issue new is outstanding,equityholdersrefuse to contributecapital

debt that is senior to all "prepetition"debt. Such for positive net present value investments because the

debtor-in-possession(DIP) financing is valuable returns will accrue largely to bondholders.This is the

because the firmcan borrowon cheapertermsthan underinvestmentproblemstudiedby Myers [94], and sub-

withoutit.

sequently by John and Kalay [72]. The second problem

(iv) The interest on prepetitionunsecureddebt stops (introduced by Jensen and Meckling [69]) is that

accruingwhile the firmis in bankruptcy,freeingup equityholdersmay overinvestin riskyprojects,i.e., under-

scarce cash. For a detailed discussion of the fea- take risky but negative net present value projects when

tures of the Chapter11 process, see Gilson, John, risky debt is outstanding. Problems of risk-shifting or

and Lang [55] or White [113], [114]. excessive continuationare differentmanifestationsof the

An emergingliteraturein law andfinancequestionsthe same problemof overinvestment.

optimalityand efficiency of the existing bankruptcyreor- Bulow and Shoven [34] and White [111], [112] were

ganizationprocess and proposesalternativesystems. This among the first to point out thatthe featuresof the bank-

literatureis surveyedin Section IV.A.EberhartandSenbet ruptcycode will affect investmentdecisions by distressed

[43] contributeto this literature.The empiricalevidence firms. Bulow and Shoven [34] and White [111], [112]

on the Chapter11 process and its efficiency is surveyedin argue that the coalition of equity and the bank makes

Section IV.B. A summary of Bi and Levy [26] is also continuation decisions based on its private gains from

includedthere.Aspects of financialdistressamongbanks restructuring.This decisionto continueor to liquidatemay

andturnaroundstrategiesarealso discussedin thatsection, not be efficient. Coordinationproblemswhich arise in the

along with the contributionsof DeGennaro, Lang, and presenceof multiplecreditorsareanalyzedin Gertnerand

Thomson [38] and Barrowand Horvitz [17]. Scharfstein[50] and Bolton and Scharfstein[28]. Gertner

and Scharfstein[50] arguethat the benefit of bankruptcy

A. Efficiencyof the BankruptcyProcedure is that, in Chapter 11, unanimity of debtholdersis not

Financial contracts specify how resources are to be requiredto effect changes in the debt contract.This miti-

allocatedbetween investorsand firms.Bankruptcyproce- gates holdoutproblemsand, along with the otherfeatures

dureswhich governthe breachof contractualpromisesare of currentbankruptcylaw (automaticstay and violations

generally containedin the legal system and not specified of absolutepriorityrule), tends to increaseinvestment.

The net benefit of such increasedinvestmentdepends

on the incentives generated by the characteristicsof

9The absolute priority rule (APR) states that creditorsshould be fully

contracts-in-place,such as maturitystructure,covenants

compensatedbefore shareholdersreceive any portion of the bankrupt

firm'svalue.Recentempiricalstudies,however,have shownthatthis rule and the priorityof privateversus public debt. The Bank-

is seldom followed (see Section IV.B.). ruptcyCode improvesefficiency when underinvestmentis

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOHN/ MANAGING

FINANCIAL

DISTRESS 69

a problem(e.g., when the firmhas short-termpublic debt, the argumentsover valuationand liquidationare avoided,

senior bank debt, and the public debt has senioritycove- the risk-shiftingincentives in investmentpolicy induced

nants). by APR allocation will remain prior to entering bank-

Berkovitchand Israel[22] show thatfirmsfacing over- ruptcy.To strikea balance between conflicting efficiency

investmentincentives are more likely to file for Chapter objectives, White [113] proposes biasing the allocation

11 protection,while firms facing underinvestmentincen- towardsequity and managementdeviatingfrom strictad-

tives aremore likely to renegotiatein a workout.Bebchuk herence to APR (similar in spirit to Eberhartand Senbet

[19] points to more acute incentives to overinvestin the [43]). Zender[117], Aghion andBolton [1], andKalayand

presence of deviationsfrom absolutepriorityrules, when Zender[83] deriveoptimalcontractsunderwhich control

firms are not in financialdistress. of the firm is transferredand claims are adjustedwhen

Eberhartand Senbet [43] demonstratein a contingent performanceis sufficientlypoor.The above studies really

claims framework,thatAPR violationsplay an important address the question of an efficient process of resolving

role in amelioratingthe shareholder/bondholder agency financial distress, given the firm is in financial distress.

conflict. Specifically, departuresfrom the APR mitigate However a bankruptcyprocess which resolves financial

the incentivefor shareholdersto increasethe risk of finan- distress efficiently is only consideringhalf the picture.If

cially distressedfirms.Moreover,the effectiveness of this resolutionof defaultis maderelativelycostless thenit may

mitigation increases as the firm approachesbankruptcy encouragedefaulttoo often andraisingfinancingformany

and as traditionalmethods,such as conversionprivileges, worthwhileprojectsmay become difficult.In otherwords,

lose effectiveness. Berkovitchand Israel [22], and Kalay there may be a tension between efficiency of ex post

and Zender[83] make relatedarguments. resolution of default and ex ante contractualefficiency.

Most of the papers summarizedabove take the bank- This has to be a considerationin the design of an optimal

ruptcy procedure as a given and examine its effect on bankruptcylaw.11

aspects of investmentefficiency. Anothergrowing litera- A relatedpoint is that optimal bankruptcylaw cannot

ture has begun to address issues of optimal design of be analyzed independentlyof optimal security design.

bankruptcyrules.Bebchuk[18], White [113], Bradleyand After all, bankruptcylaw specifies rules governing the

Rosenzweig [29], Aghion et al [2], Zender[117], Aghion breachof stipulatedcontractualtermsin specific financial

and Bolton [1], Kalay and Zender [83], Harrisand Raviv contracts. For example, debt contracts specify the

[59], Altman [12], Easterbrook[42], Merton [91], and debtholder'sinvestment,the specific paymentsto which

Berkovitch, Israel, and Zender [23] are attempts in this he is entitled, and covenantsincludingconstraintson the

direction. borrower's behavior (see John and Kalay [72]). Bank-

Roe [100], Bebchuk [18], White [113], Bradley and ruptcyrules specify the legal proceduresto be followed if

Rosenzweig [29], and Aghion et al [2] containproposals the promisedpaymentsare not made or if the covenants

of reformwhich involve implementinga "textbook"pro- are violated. Therefore,design of an optimalbankruptcy

cedureof selling the firmanddividingthe proceedsamong procedure should be viewed in combination with the

creditorsand old equityholdersaccordingto the APR. The broaderproblemof optimalcontractdesign.

new owners of the firm would make decisions about HarrisandRaviv [59] takean importantfirststep in this

whetherto continueoperationsor liquidateandwhetherto directionof designingan optimalbankruptcyprocedureas

retain the old managersor to replace them. They would a part of an overall contractdesign problem. They ap-

choose the alternativeswith the highest value. An advan- proachthe problemof contractdesign as one of choosing

tage of these proposalsis thatthe firm would end up with a game to be played among the partiesto the contractas

an all-equitycapital structureat the end of the bankruptcy opposed to choosing a contingentallocations scheme. In

procedure which would avoid the waste and delays of anenvironmentof incompletecontracting(wherethereare

intergroupconflictsandprotractedbargaining.10Although restrictionson the kinds allocationschemes which can be

enforced), the allocations of resourcescan sometimes be

loAghion,Hart,and Moore [2] and Altman [12] contain evaluationsof

some of these reformproposals.Easterbrook[42] arguesthatthe cost of

liquidationsandauctionsmay be largeenoughtojustify the currentcostly 1"Bolton and Scharfstein[28] use this trade-offin their analysisof some

bankruptcyprocess. Roe [101], Baird [16], Bebchuk [18], Bradleyand aspects of debt structure:the numberof creditorsa company borrows

Rosenzweig [29], and Weiss [110] criticize the existing bankruptcy from; the allocationof security interestamong creditors;the intercredit

procedure. covenantsgoverningrenegotiationof debt contracts.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70 FINANCIAL

MANAGEMENT

/ AUTUMN1993

improvedby designing a game in which players respond Whendebtis restructured

increasingequityorconvertible

to actions and/or statementsmade by other players. The components,the incentivefeaturesin the compensation

improvementis possible because equilibriumstrategies, structureshould be significantly increased. Gilson and

and hence outcomes, can depend on aspects of the envi- Vetsuypens[56] documentempiricalevidence consistent

ronment even though allocation schemes contingent on with these predictions.

such aspects are not enforceable.

The setting of the Harrisand Raviv model, similar to

thatin HartandMoore [60], is thatof an entrepreneurwho

B. EmpiricalEvidenceon the Chapter11

needs outside financing for a positive net present value Process

project.The cash flows generatedare appropriableby the The empiricalwork on the formal bankruptcyprocess

has been primarily on (i) direct and indirect costs of

entrepreneurbut not the proceeds from liquidation of

assets. The threat of seizing and liquidating the firm's bankruptcy,(ii) announcementeffects of bankruptcyfil-

assets (whicheliminatesa correspondingfractionof future ings, (iii) deviations from absolute priorityrule, and (iv)

cash flows) is the only way to induce the entrepreneurto efficiency of bankruptcyreorganizations.

pay out cash to investors. Since liquidation is strictly The legal, administrativeandadvisoryfees thatthe firm

suboptimalin every state of the world, an optimal bank- bears as a direct result of entering and undergoingthe

ruptcyprocedurewouldbe one whichminimizestheextent formalbankruptcyprocesshave been called "directbank-

of liquidation while providing sufficient payouts (cash ruptcy costs." Warner [108], [109] studies 11 railroad

and/orliquidationproceeds)to induceinvestorsto contrib- bankruptciesduring 1933 to 1955 and finds the average

ute the requiredcapital. Harrisand Raviv [59] show that directcosts to be about5.3% of firm'smarketvalue at the

debt with a bankruptcycourtwhich can impose violations time of the bankruptcyfiling. Ang et al [14] investigatea

of APR is a Pareto improvementrelative to contracts sample of 86 firms that filed for bankruptcy(and eventu-

without a bankruptcycourt.The additional,limited state- ally liquidated)in the WesternDistrict of Oklahomabe-

tween 1963 and 1979. Theyreportmeanandmediandirect

contingency achieved by the presence of a bankruptcy

court is shown to be sufficientto achieve optimal alloca- costs (as a percentage of total liquidationproceeds) of

tions in the Harrisand Raviv [59] environment.12 7.5% and 1.7%, respectively. More recently, Ferris,

Berkovitch, Israel, and Zender [23] argue that bank- Jayaraman,andMakhija[46] reportlargerdirectadminis-

trative costs of bankruptcyfor small firms, based on a

ruptcy law with a managementbias (which places the

managerin a favorablebargainingposition in renegotia- sampleof liquidationsand reorganizationsthatwere filed

tions) plays a role in providing the manager with the during 1981-1991 in the U.S. BankruptcyCourt(Western

correctex ante decision-makingincentives.Withoutsuch District of Tennessee). Their mean (median) costs are

a commitmentfeature of the bankruptcylaw, managers 27.73% (0.91%) of the assets reportedat the initiationof

will underinvestin developing firm-specifichumancapi- bankruptcy,and 41.49% (25.65%) of the total disburse-

ments at the end of the process. For reorganizations,they

tal.

find thatthe mean (median)costs are 21.55% (1.88%) of

JohnandJohn [78] studythe dynamicsof top-manage-

the reportedassets, and 15.10%(3.41%) of the total dis-

ment compensationin firms going throughfinancial dis-

bursements.These are higher than previously reported

tress. They arguethatthe amountand structureof external

estimates for reorganizationsby small and large firms.

claims outstandingaffect the design of top-management

Weiss [109] analyzes a sample of 37 firms that filed for

compensation.If the externalclaim is riskydebt,top-man-

bankruptcybetween 1980 and 1986, and finds average

agementcompensationshouldhave incentivefeaturesand directcosts to be 2.9%of the book value of assets priorto

pay-performancesensitivitythataredecreasingin the debt

filing.

ratioof the firm.When the firm is in financialdistress,the

Indirectcosts of bankruptcyareopportunitycosts aris-

pay-performancesensitivity should be extremely low.

ing from suboptimalactions associated with bankruptcy,

e.g., the firmlost its firstmoveradvantagein developinga

'2Inthe HarrisandRaviv [59] environment,any legal structurewhich can new productto a competitorwhen it was going throughthe

induce the additional(possibly limited) state-contingencyin outcomes

formal bankruptcyprocess. Lost sales and competitive

will accomplishthe optimalallocation,with a correspondingcontract.In

this sense, theirsolutionis not specific enoughto pinpointthe"attractive" advantage,higher operatingcosts, lost investmentoppor-

featuresthat a good bankruptcyprocedureshouldhave. Furtherwork is tunities,and loss of consumerconfidence are all potential

requiredin this area. indirectcosts. Gilson, John, and Lang [55] argue that all

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DISTRESS

FINANCIAL

JOHN/ MANAGING 71

value lost throughdestructionof going-concernvalue rep- ber of recent studies document that APR is frequently

resentsindirectbankruptcycosts. They use "marketvalue violated in Chapter11 reorganizationsand informaldebt

+ replacementcosts"as a proxyfor these costs. Altman[8] restructurings,e.g., see Franksand Torous[47], Eberhart,

measuresthe differencebetween the earningsrealized in Moore, and Roenfeldt [44], and Weiss [109]. Eberhart,

each of the three years priorto bankruptcyand earnings Moore, and Roenfeldt [44] find that APR violations ac-

that could have been expected at the beginningof each of countfor 7.6%of the totalamountpaidout to all claimants

those years, to compute indirectcosts of bankruptcy.All and that they are anticipatedby investorsex ante. Franks

deviations of actual profits from their expected counter- and Torous[48] documentthatthe rateof APR violations

partsaredenotedas indirectcosts of bankruptcy.Although is largerin informalworkouts(+9%) comparedto that in

a good startingpoint, such a definitionwould include all Chapter11 reorganizations(+4%).

deviations from expected profits (even those which are Betker [25] explores the cross-sectionaldeterminants

unrelatedto financing). of equity's deviationfrom absolutepriorityin 75 Chapter

A numberof studies document a significant negative 11 reorganizations.EmpiricalevidenceindicatesthatAPR

abnormal return (around -16%) on announcement of deviation is larger when: the firm is closer to solvency;

bankruptcyfiling (e.g., Clarkand Weinstein[35], Gilson, bankshold fewer claims; the CEO holds more shares;the

John,and Lang [55], and Eberhart,Moore, and Roenfeldt firm'soriginalCEOis retainedor replacedfrom inside the

[44]). Bankruptcy announcement effects on the share firm;and CEO pay and shareholderwealth are positively

prices of competingfirmshave been investigatedby Lang related.See also LoPuckiand Whitford[89].13

and Stulz [86] (and in a small sample earlierby Aharony

and Swary [3]). Lang and Stulz [86] document that the Systematic empirical evidence on the efficiency of

bankruptcyreorganizationswould be importantto the

equity value of competing firms in the industry of the

study of mechanismsfor managingfinancialdistressand

bankruptfirm decreasedon the averageby one percentat

the time of bankruptcyannouncement.However,the stock understandingthe design of optimal bankruptcyproce-

dures. Hotchkiss [64], [65] contain the only available

prices of competing firms with low leverage in highly

evidence on the post-reorganizationperformanceof firms

concentratedindustriesincreasedby 2.2%.

In this special issue, Bi and Levy [26] examine the emerging from Chapter11. In Hotchkiss [65], she exam-

ines the performance of 197 public companies which

announcement effect of bond downgradings on stock

prices of downgradedfirms.Theirresultsprovideinsights emergedfrom Chapter11 bankruptcy.Almost 40% of the

into the dynamicsof the ratingprocess used by the rating samplefirmscontinueto experienceoperatinglosses in the

two years following bankruptcy,while over 16%file for

agencies, Moody's and Standard& Poor's. Their results

show thatthe averageabnormalreturnof the subsampleof Chapter11 for a second time. Managementoften retains

firms which subsequentlyfile for Chapter11 bankruptcy substantialinfluence over restructuringdecisions during

is significantlymore negativethanthe matchingsampleof bankruptcy,and frequentlyis not replaceduntil a plan of

firms which had a similardowngradingbut did not file for reorganizationhas been confirmed. The continued in-

Chapter11. Althoughthe authorsinterprettheirresultsto volvement of pre-bankruptcymanagementin the restruc-

signify that the market'sinformationis finer than that of turingprocess is stronglyassociatedwith poor post-bank-

the ratings agency, it may have more to do with the ruptcy performance. The substantial number of firms

dynamics of the ratingsprocess. If the ratings agency is emergingfrom Chapter11 which are not viable or which

conservativein their downgradings,such that the down- need furtherrestructuringsuggeststhattheremay be a bias

gradings are done in multiple stages, then the marketis towardcontinuationof unprofitablefirms. The evidence

simply reactingappropriatelyto the informationwhich is does not indicatethatthe Chapter11 reorganizationplays

already available to the market and the rating agency, an effective role in rehabilitatingdistressedfirms.

althoughnot fully reflectedin the partialinitialdowngrad-

ing. 13Anumberof theoreticalstudies (see, e.g., Brown [30], Giammarino

According to the absolute priorityrule (APR) of allo- [52], John and Vasudevan[74], and Bergman and Callen [20], [21])

cating the value of a bankruptfirm, the senior claimants suggestthatAPRviolationsare,in fact,rationalresponsesby bondholders

and the courts to debtor-managementbargainingpower engenderedby

receivetheirfull contractualpromisedpaymentbeforeany

the formalreorganizationprocess. Harrisand Raviv [59] arguethatAPR

class with a morejuniorclaim receives anything.Although violations may be partof an optimallydesigned bankruptcyprocedure.

APR is followed strictlyin Chapter7 liquidations,a num- See also Eberhartand Senbet [43].

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72 FINANCIAL / AUTUMN1993

MANAGEMENT

Massive numbers of insolvencies have plagued the which have defaultedon theirdebt and/orfiled for protec-

thriftindustry(savings& loans (S&Ls)andmutualsavings tion underChapter11 bankruptcyas approximately$20.5

banks)throughoutthe 1980s and into the 1990s, which has billion ($42.6 billion in face value). Securitieswhichyield

led to the depletionof the governmentfund establishedto a minimum ten percent over comparablematurityU.S.

insure the deposits in these institutions.The costs of re- Treasurybonds, i.e., 16.6% or above, are estimated to

solving the thriftinsurancemess are estimatedto be $125 amountto $71 billion in parvalue (with severalissuersand

billion to $150 billion. Unlike industrialfirms in financial 600 issues) and about$37 billion in marketvalue. Adding

distress, which undertakeasset and/ordebt restructuring, privatedebt with public registrationrights, privatebank

thriftsoften operatein an insolventconditionfor extended debt and tradeclaims of defaultedand distressedcompa-

periods.DeGennaro,Lang,andThomson[38] andBarrow nies bringsthe totalbook value of defaultedanddistressed

and Horvitz [17] examine turnaroundstrategiesused by securitiesto $284 billion (marketvalue, $177 billion).14

troubledthriftsand theireffectiveness. Althoughthe markethas attracteda lot of attentionfrom

DeGennaroet al [38] examine a sample of 300 large investors, researchon models of valuationfor securities

insolventthrifts,of which 24%recoveredbetweenthe end with significantprobabilityof default is still preliminary.

of 1979 andthe end of 1989. They contrastthe turnaround Altman [9] underscoresthe institutionalfactorsof default,

strategiesadoptedby these recoveredinstitutionsto those restructuringandbankruptcyreorganizationsas important

used by thriftsthatfailed. When the crisis surfacedin the in valuing these securities.However,the existing models

early 1980s, these recoveringfirms operatedin a fashion of high-yield bonds do not explicitly incorporatethese

similarto failing firms.However,in the mid-i1980s,recov- factors in the valuationmodels. This is an importantarea

ering thriftspursuedrisk-minimizingstrategieswhile the for furtherresearch.

nonrecoveringthrifts pursued risky, high-growth strate- An importantingredientof valuationwhich has been

gies. They find no evidence thatmanagersof nonrecover- examined in the existing literatureis the probabilityof

ing thriftsconsumed more perquisitesthan their counter- default. Numerous studies have developed models that

parts. estimate the probabilityof default. Market-relatedmea-

Barrowand Horvitz [17] examine the performanceof sures of bond default probabilitieshave complemented

insolventthriftsunderthe ManagementConsignmentPro- traditionalcredit techniques which concentrateon firm-

gram (MCP). MCP was adopted,in 1985, by the Federal specific aspects of bonds. Creditquality upon initial issu-

Savings and Loan InsuranceCorporation(FSLIC) in an ance, that for seasoned bonds, bond rating changes over

attemptto minimize the acute adverseincentiveproblems time driven by changes in default probabilities,actual

present when insolvent thrift institutionsare allowed to default rate of bonds, have all been documented (see

continue in operation.The new managementteams, se- Altman [7], [10], and Altman,Eberhart,and Zekavat[13]

lected by federalregulatorsandcompensatedon a contract for a review of this literature).Altman, Eberhart,and

basis, were expectedto maintainservice to depositors,and Zekavat[13] studythe severityof defaultfor91 firms(with

improve the condition of the thrift's books and records, 232 bonds) that defaultedand emerged from Chapter 11

while more permanentsolutionswere explored. betweenJanuary1980 andJuly 1992.They documenttotal

The evidence indicates that the chances of the MCP losses investorswouldhave incurredif they boughta bond

institutions recovering to solvency were significantly at issuance and held it until completion of bankruptcy

lower than the chances of similarlyinsolvent institutions reorganization.

thatwere allowed to operateoutside of directgovernment Many of the previousstudies (see Altman [10, Ch. 6])

control.The authorsarguethatthis is a consequenceof the estimate the unconditionalprobabilitythata firm will file

absence of a profit motive and the induced conservative bankruptcy.These studiesgenerallyanalyzematchedsam-

strategiesunderMCP. ples of bankruptandnonbankruptfirms,using accounting

informationand other firm characteristicsas explanatory

V.Valuationof Distressed Securities

As the numberand diversity of financially distressed 14Theseestimatesare from Altman [11]. Altman[9], 11] also describes

firmshave increased,the marketfor distressedfirms'debt the market for these securities and analyzes their performance.The

Altman-MerrillLynch & Co. Index of Defaulted Debt Securities(mar-

andequitysecuritieshas capturedthe interestof the invest-

ket-weightedmeasureof 233 differentdefaultedsecuritiesfrom 89 firms)

ment community.As of August 31, 1992, Altman [11] is reported on a monthly basis by Merrill Lynch and also on the

estimates the marketvalue of the debt securitiesof firms Bloombergsystem. See also Altman [10].

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FINANCIAL

JOHN/ MANAGING DISTRESS 73

variables.Gilson, John, and Lang [55] estimate the prob- option pricing theory to value corporateliabilities with

ability of Chapter 11 conditional on the firm being in various contractualfeatures. Merton [90] examined the

financialdistress.They studyhow asset andliabilitystruc- risk structureof interestrates and Ingersoll [66] used this

tures help predict whether financial distress is resolved correspondenceto valueconvertibleandcallablecorporate

througha privateworkoutor throughformal bankruptcy liabilities. These arejust two examplesof the valuationof

underChapter11. corporatesecuritieswhich may be addressedusing option

A contributionin this area is made by Coats and Fant pricing theory (see Park and Subrahmanyam[98] for a

[36]. They apply a "neuralnetwork"to the estimationof surveyof this literature).

the futurefiscal healthof corporations.The distinctadvan- While the insights offered by this researchare import-

tages of this new methodology for recognizing arbitrary ant,the abilityof this approachto explainthe yield spreads

discriminatingpatternsin financial data are highlighted. between corporate bonds and comparable default-free

The commonly used tool for classificationand prediction Treasurybondshas been questionedin recentpapers.The

is a multiple discriminantanalysis (MDA) of financial empirical findings of Jones, Mason, and Rosenfeld [80]

ratios. But the MDA technique has limitations deriving indicatethatexisting contingentclaims pricingmodels do

from its relianceon the assumptionsof linearseparability, not generatethe levels of yield spreadswhich one observes

multivariatenormality,andindependenceof the predictive in practice.Over the 1926-1986 period, the yield spreads

variables. A neural network, being free from such con- on high-gradecorporates(AAA-rated)rangedfrom 15 to

215 basispointsandaveraged77 basispoints;andtheyield

strainingassumptions,is able to achieve superiorresults.

The neuralnetworkmodel in theirpaperuses the Cascade- spreadson BAAs (also investment-grade)rangedfrom 51

Correlationapproachin Fahlmanand Lebiere [45]. to 787 basis points, and averaged 198 points. Kim,

An importantdeterminantof the value of distressed Ramaswamy,and Sundaresan[85] show that the conven-

securities is the lack of liquidity and marketability(see tional contingent claims model due to Merton [90] is

Altman [10]). This is also an importantinstitutionalfactor unableto generatedefaultpremiumsin excess of 120 basis

which has not been incorporatedinto the valuationmodels points, even when excessive debt ratios and volatility

of distressedsecurities.Shulman,Bayless, andPrice [103] parametersare used in the numericalsimulation.

take an importantstep in this direction.They examine the The contingentclaims models mentionedabove do not

determinantsof yields, relativeto Treasuries,for an exten- incorporatemany real world institutionalfeatures of de-

sive sampleof individual,seasoned,high-yieldbonds.The faultandthe Chapter11 bankruptcy.The settingallows for

no frictions as in Miller and Modigliani [93]. The typical

impactof defaulton yield spreadsfor individualhigh-yield

bonds is incorporatedusing a default model which pro- boundaryconditionused in these models to denote bank-

duces an expected probabilityof default for each bond. ruptcyis thatof strictabsolutepriorityrule triggeredwhen

Default risk, along with marketabilityrisk and otherchar- firm value falls below the promisedprincipalpayment.15

The entire firm value without any liquidation costs is

acteristics on yield spreads is modelled using a factor

assumed to be passed to bondholders in default. This

analytic (LISREL)technique.The empiricalresults indi-

cate that both marketabilityrisk and default risk are im- assumption is at odds with reality in several important

ways: (i) as definedin Section I, the cash-flow criterionof

portantin explaining yield spreadsfor high-yield bonds. default happens when the currentliquidity of the firm is

Additional refinements among criteria discussed in this

inadequateto meet its currentobligations, say, required

paper should lead to a more rigorousanalysis of market-

coupon payments; (ii) asset liquidationsinvolve signifi-

ability and betterpricing of high-yield bonds. cant costs of liquidityandloss of going-concernvalue (see

Since default risk and the losses to bondholders in

Section II); (iii) there are importantstrategic aspects to

default are importantdeterminantsof high-yield debt, a

defaults,debtrenegotiations(in privateworkoutsor Chap-

large traditionalliteraturehas focused on the probability ter 11 reorganizations)and liquidationswhich affect allo-

of defaultfrom asset andliabilitycharacteristicsand other

cation of value (see Section III); (iv) there are significant

financialratios of the firm. However,these techniquesdo

deviationsfrom absolutepriorityrule in the allocationsin

not value completely the defaultrisk definedby the prob-

the bankruptcyprocess (see Section IV.B.).These institu-

ability of default as well as the payout at default. The tional features of default and its resolution should be

correspondencebetween the option to defaultin corporate

bondsunderlimitedliabilityandstock options,recognized

in Black and Scholes [27], led to many applicationsof the 15Geske [51] considerscoupon defaults,as well.

This content downloaded from 185.44.79.22 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 15:09:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

74 FINANCIAL

MANAGEMENT

/ AUTUMN1993

incorporatedinto valuationmodels of securitieswhich are poorerperformance?How do these strategiesaf-

in distress or have a high probabilityof distress. To my fect firm performanceafter distress and/orbank-

knowledge, none of the existing models accomplish this ruptcyreorganization?17 (See Section II.)

task. (ii) Thereis some documentedevidencethatthe nature

Kim, Ramaswamy,and Sundaresan[85] take an im- of the debt contract,the complexity of the capital

portantstep in this direction.They incorporatefeature(i) structure, the number of creditors involved,

above into their model and focus on the default risk of whetherthe debt is publicor privatedebt andwhat

coupons in the presence of dividends and interest rate fractionof debt is bankdebt, are all factorswhich

uncertainty.Numerical solutions are employed to show could affect the success of a relatively low-cost

thatthe resultingyield spreadsare sensitiveto interestrate

privateworkout.Empiricalwork relatingfeatures