Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Academy of Accounting Historians

Uploaded by

Đạt LêOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Academy of Accounting Historians

Uploaded by

Đạt LêCopyright:

Available Formats

The Academy of Accounting Historians

PROFESSIONAL LEADERSHIP AND OLIGARCHY: THE CASE OF THE ICAEW

Author(s): Masayoshi Noguchi and John Richard Edwards

Source: The Accounting Historians Journal, Vol. 35, No. 2 (December 2008), pp. 1-42

Published by: The Academy of Accounting Historians

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40698390 .

Accessed: 14/06/2014 12:56

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Academy of Accounting Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Accounting Historians Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Accounting HistoriansJournal

Vol.35, No.2

December2008

pp. 1-42

MasayoshiNoguchi

TOKYO METROPOLITANUNIVERSITY

and

JohnRichardEdwards

CARDIFFBUSINESS SCHOOL

PROFESSIONAL LEADERSHIP AND

OLIGARCHY: THE CASE OF THE ICAEW

Abstract: This paper examinesthe difficultyof achievingrepresenta-

tiveand effective governanceof a professionalbody.The collective

studiedforthispurposeis the Instituteof CharteredAccountantsin

England and Wales (formed1880) which,throughoutits existence,

has possessedthe largestmembershipamongBritishaccountingas-

sociations.Drawingon the politicaltheoryof organization,we will

explainwhy,despitea seriesof measurestakento maketheconstitu-

tion of its Councilmorerepresentative betweenformationdate and

1970,the failureof the 1970 schemeforintegrating the entireU.K.

accountancyprofessionremainedattributable to the "detachment of

officebearersfromtheirconstituents" [Shackletonand Walker,2001,

p. 277]. We also tracethe failureof attemptsto restorethe Council's

authority overa periodapproachingfourdecades sincethat"disaster"

occurred[Accountancy , September1970,p. 637].

INTRODUCTION

Voluntary associationsin commonwithorganizationalenti-

ties in generalhave at the apex of theiradministrative structure

a bodychargedwiththeresponsibility of leadership.In the case

of professionalassociations,such leadershiphas as a central

motivationthe pursuitof the professionalprojecton behalfof

itsmembers.However,Macdonald [1995,pp. 57-58,204-205]ex-

plainshow themembershipofa professionalbodycan constrain

the capacityof its leadershipto mobilize economic,social, po-

Acknowledgments:We expressour gratitudeand appreciationto Stephen

P. Walker,TrevorBoyns,Roy Chandler,and MalcolmAndersonforconstructive

commentsmade at draftstagesof thispaper.This studyhas also benefitedfrom

helpfulcommentsmade byparticipants at the2004 WorldCongressofAccount-

ing Historiansin St. Louis and Oxford,the 2004 AnnualConferenceof the As-

sociationofAccounting Historiansat TokyoMetropolitan Japan,and

University,

fromtheinputsoftwoanonymousreferees.FinancialsupportfromtheInstitute

of CharteredAccountantsof Scotland and Daiwa Anglo- JapaneseFoundation

(smallgrantref:4949) is gratefully

acknowledged.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

liticai,and organizationalresourcesin pursuitof a professional

project.UsingtheInstituteof CharteredAccountantsin England

and Wales (ICAEW) forthis case study,we findno shortageof

examplesof this happeningin the last ten years or so. For ex-

ample, the Councils 2001 proposal to restructure the ICAEWs

traditionaldistrictsocietysystemwas overtlychallengedand

contendedin a poll [Accountancy, August2001, p. 12]. Councils

plans in1996 and 1999 to introduceélectives(optionalpapers)

into the ICAEWs finalexaminationsmet strongoppositionand

were rejectedby the membership[Accountancy, February1996,

p. 11; July1999,p. 6]. Indeed,membershave been proactiveas

well as reactivein challengingthe authorityof Council. Initia-

tivestakenin 1996 and 1998,designedto achievedirectelection

of the ICAEW presidentby the membershipratherthan by the

Council,althoughdefeatedin a poll,have been judged to effecta

diminutionof its credibility[Accountancy,February1996,p. 12;

July1998,p. 20].

Momentouseventsthatfurther highlightthe persistentlack

of authorityon the part of the Council are the series of failed

mergerinitiatives, includinga numberin the recentpast,where

the aspirationsof the ICAEWs leadershipwere thwartedby the

membership.The fragmentedorganizationalstructureof the

U.K. accountancyprofessioncan be tracedto the diversenature

of the work undertakenby Britishaccountantsin the second

half of the 19th century[Edwards and Walker,2007]. Merger

initiativeshave been intendedto reducetheplethoraof societies

which,forexample,totaledat least 17 in theearly1930s [Stacey,

1954,p. 138] and, as a result,producetheadvantagesassociated

with a more unifiedaccountancyprofession[Shackletonand

Walker,2001, p. 166; Council MinutesBook Y, p. 148]. There

have of course been importantinstancesof successfulmergers

whichincludeamalgamationofthefivesocietiesformedin Eng-

lish cities(Liverpool,London,Manchester, and Sheffield)during

the 1870sto createtheICAEW in 1880;combinationofthethree

city-based(Aberdeen,Edinburgh,and Glasgow)societiesformed

in Scotland in the 19thcenturyto createthe Instituteof Char-

teredAccountantsof Scotland(ICAS) in 1951; and themergerof

the London Associationof Accountantsand the Corporationof

Accountantsin Scotlandto form,in 1939,what is todayknown

as theAssociationof CharteredCertified Accountants[Edwards,

2003]. The only other major reorganizationof the Britishac-

countingprofessionoccurredin 1957 when the second largest

accountancybody in Britain,the Society of IncorporatedAc-

countantsand Auditors,was dissolvedwithits membersjoining

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 3

one or otherofthethenthreecharteredbodies.

There has been no furthermergerinvolvingany of the

seniorprofessionalbodies in Britainforhalf a century,during

which time many initiativeshave in fact been mounted only

to have then foundered.The firstof these marked an event

which serves as the focal point forthis study- the "disaster"

[Accountancy, September1970, p. 637] thatoccurredwhen the

ICAEW's membershiprejected its leaderships plan to merge

all six senior accountancybodies in 1970. Subsequent aborted

mergerplans include the ICAS with the ICAEW in 1989, the

CharteredInstituteof Public Finance and Accountancy(CIPFA)

withthe ICAEW in 1990 and 2005, and the CharteredInstitute

of ManagementAccountantswiththe ICAEW in 1996 and 2004.

The reasonsforfailureare seen to be broadlycommon,"internal

wranglingand fiercely guardedbrandvalues"[Perry, 2004].1

Everytime a proposed mergerfails,divisionbetweenthe

ICAEW Counciland its membershipis highlighted [Wild,2005],

the authorityof Councilis problematized,and morerepresenta-

tive arrangementsin the Council'scompositionare demanded.

For example,a letterpublished in Accountancy[July1996, p.

130] statedthat:

Elected but out of touch...Not only is thereno means

by which the elected Council membersdo receivethe

viewsof theirconstituents, but theirbehaviorin recent

yearshas shownthemto be seriouslyout of touchwith

members'wishes.The issue of merger,forexample,has

shown time and time again thatthe Council members

did not know,or chose to ignore,theview of theircon-

stituents.

The purposes of this studyare to explain whythe ICAEW

Council came to be "detached"fromthe interestsof the mem-

bership,lost its authoritywith the membership,and subse-

quentlyfailedto re-establishit. To achieve these objectives,the

remainderof thispaper is constructedin the followingmanner.

First,we locate our studywithinthe relevantprioraccounting

Next,we reviewgermanefeaturesofthepoliti-

historyliterature.

cal theoryof organizationto establishan analyticalframework

for examiningthe intra-organizational dynamicsbetween dif-

ferentgroupsof memberswithinthe ICAEW.We thenconsider

whetherthe ICAEW's internalregulationssucceeded in making

provisionfor a democraticallyrun organizationand identify

1See also, "Membership

'TimeBomb'DrivesICAEWMergerPlan"[2004] and

"MembersSpliton ICAEW-CIMA-CIPFA Merger"[2004].

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

4 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

and distinguishtypesof criticismsdirectedin practiceat the

representative characterof the leadershipby membersand the

professionalpress. In so doing,and by referenceto the analyti-

cal framework, we traceand analyzethe reformof the arrange-

mentsmade forthe electionof ICAEW councilorsduringthe

period priorto 1970, and considertheireffectiveness. We then

examinethe reasons forthe collapse of the schemeforintegrat-

ing theentireBritishaccountancyprofession,drawingattention

to and presentingevidenceto demonstratethe "detachmentof

officebearersfromtheirconstituents" [Shackletonand Walker,

2001, p. 277]. Finally,we examineand analyzethe failureof nu-

merousattemptsto restorethe Councils authorityovera period

approachingfourdecades sincethatcalamityoccurred.

The main primarysources consulted for the purpose of

thisstudyare located at the GuildhallLibrary,London,and the

ICAEWs officein MiltonKeynes.

INTRA-ORGANIZATIONAL

DYNAMICS IN

ACCOUNTINGHISTORY

There existsa substantialcriticalliteratureon the profes-

sionalization of accountancywhich is marked by studies of

closurestrategies2 pursuedby professionalaccountancybodies.

Many of the works ofthisgenrefocuson externalrelationships-

inter-organizational,inter-occupational, state-

and, particularly,

profession - in the endeavor to offera "coherent explanation

of why some occupations [or segments]successfullybecome

accepted as professionalizedwhilstothersdo not" [Cooper and

Robson, 1990,p. 374]. Thereis also a developingliteraturethat

spotlightsthe significanceof intra-organizational relationships

withinan accountancybody,focusing,in the main,on dichoto-

miesbetweentheleadershipand therank-and-file.

Extendingwork on closure strategies,one strand of the

studiesof internalrelationshipsexaminesthe interfacebetween

the accountingprofessionand the state. Chua and Poullaos

[1993] include an examinationof the need to address the con-

cernsof practitioners and non-practitioners when Victorianac-

countantswere attemptingto secure state recognitionby royal

charterbetween 1885 and 1906. Carnegieet al. [2003] employ

the prosopograhical method of inquiry to explain why key

membersof the IncorporatedInstituteof Accountants,Victoria,

2Murphy[1984,p. 548] definesclosureas "theprocessofmobilizingpowerin

orderto enhanceor defenda group'sshareofrewardsor resources."

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 5

transferred theirallegiance to the AustralasianCorporationof

Public Accountantsin order to betterpursue acquisition of a

charterforthose in public practice.Richardson's[1989, p. 415]

studyof the regulationof accountancy"illustratesthe relation-

ship betweenthe internalsocial orderof the professionand its

involvement in corporatiststructuresin one particularjurisdic-

tion/'that of Ontario,Canada. He draws on Gramsci'stheory

of hegemonyto examinethe way in which consentwas manu-

facturedand dissentmanagedduringcreationof the Public Ac-

countantsCouncil. Shackleton's[1995, p. 40] studyof Scottish

charteredaccountantsup to World War I reveals "significant

schisms"withinthe membershipof the dominantSociety of

Accountantsin Edinburgh that problematized relationships

withthestateovertheperiod 1853-1916.Noguchiand Edwards'

[2004a] studyoftheICAEW leadership'sdetermination to ensure

thatits 1944 submissionto the Cohen Committeeon Company

Law Amendment was consistentwithstateprioritiesresultedin

rejectionof unwelcomeproposalsput forwardby districtsociet-

ies and refusalof requeststo make independentsubmissions.

Noguchi and Edwards [2004b] reveal disagreementbetween

practicingand industrialmembersconcerninghow to tacklethe

pressingissue of inflationaccountingbetween 1948 and 1966,

and demonstratehow the Council of the ICAEW resolvedthis

internalconflictwithinthe constraintsimposed by the need to

be seen to behavein the"publicinterest."

A second typeof intra-organizational investigationfocuses

on the interactionbetweenthe leadershipand the membership

of an accountancybody overcontentiousissues such as merger

withotherprofessionalassociations.Often,a keyconcernof the

membersis the loss of productbrandingwhichis deemed to be

an importantpartof members'identityin the marketplaceand,

therefore,"infusedwith value" [Richardsonand Jones,2007,

pp. 135-136].Richardsonand Jonesshow the process through

which the 2004 proposed mergerbetweenthe Canadian Insti-

tuteof CharteredAccountantsand CMA Canada failed,"largely

because of the reactionof membersof each association to ei-

therthe potentialloss of theirdesignation[in orderto join the

mergedbody]or thedilutionof their'brand'equity[bygranting

thecontinuingdesignationto new membersthroughthemerger

ratherthan throughtraditionalentryprocesses]."In the U.S.,

the AICPA'sglobal credentialinitiativewas put to a vote, in

January2002, which "revealeda startlingdisconnectbetween

theeliteof theprofessionand themembersin whose name they

claimed to work" [Fogartyet al., 2006, p. 16; see also, Shafer

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

6 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

and Gendron,2005]. Withinthe Britishcontext,Shackletonand

Walkers[2001, p. 235] studyof the period 1957-1970explains

how HenryBensons early (1966) acknowledgmentof the fact

thatthe merger"proposalswould initiallyinvolvedilutionand,

therefore, a reductionin statusas a startingpoint"provedtoo

bittera pill forICAEW membersto swallow.

Following the second line of investigation,this study

conductsa theoretically informedanalysis of conflictof inter-

est betweendifferent groups of the membershiparisingfrom

the constitutionalarrangementsmade for the election of the

ICAEWs Council.In thenextsection,we reviewrelevantaspects

of the politicaltheoryof organizationto establishthe analytical

framework forthisstudy.

POLITICAL THEORY OF ORGANIZATION

Building on Max Webers thesis on bureaucracy,Michels

[1962, p. 365] formulateda political theorycalled "the iron

law of oligarchy"in his book PoliticalParties,firstpublishedin

1911. "Whoeversays organization,says oligarchy,"he argued,

on the groundsthatall formsof organization,as the inevitable

outcomeof theirgrowth,eventuallydevelop into an oligarchic

polity despite the continued existence of formal democratic

practices.Jenkins[1977,p. 569] called thisfacetofMichels'iron

law the "organizationaltransformation" thesis. Scott [2003, p.

343] agrees that "most unions, most professionalassociations

and other types of voluntaryassociations,and most political

partiesexhibitoligarchicalleadershipstructures."

Emergenceof Oligarchy.Following Cassinelli [1953], Jenkins

[1977,p. 571] definesoligarchyas "theabilityofa minority in an

organization,generally the formal leadership,to make decisions

freeof controlsexercisedby the remainderof the organization,

generallythe membership,"and furtherexplains:"For a volun-

taryorganizationofficially committedto pursuingthe interests

of members...oligarchymeans thatthe policies of the organiza-

tion reflectthe preferencesof elites ratherthan the views and

interestsofitsmembers."3

Oligarchyemergesbecause leadersof the organizationwish

to maintaintheirplace on the rulingbodyand "because the po-

sitionsprovidethemwitheconomic rewardsand social status"

3Leach [2005,p. 316] statedthat"oligarchy

is bestunderstoodas a particular

distributionofillegitimatepowerthathas becomeentrenched overtime."

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 7

[Osterman,2006, p. 623]. Once leaders are appointed,theyuse

theirpositionto maintain,or ifpossibleenhance,theirpoweror

attendantprestigeby controllingthe flowof information within

the organization and mobilizing their political and organi-

zational resources,withthe resultthatthe rank-and-file of the

organization are of

deprived opportunities to exerciseits own

to

power challenge the et

leadership[Lipset al., 1956]. Accord-

ingto Jenkins[1977,p. 569]:

As the organizationexperiencesmembershipincrease,

the abilityof membersto participatedirectlyin the

makingof policyis curtailed.The membersmay retain

formalcontrolthroughthe election of officers.How-

ever, growth also entails installation of centralized

means of communicationand formalizedprocedures.

Both of thesefactorsinsulateofficersfromcontrolsby

membersdespite the check of periodic elections. Of-

ficerscan use centralizedcommunicationsto control

the agenda of issues and can block challengesthrough

formalproceduresand administrative co-optation.

Importantly, the leaders have the power to co-opt junior

officialswho share theirvalues and orientation,withthe result

thattheoligarchybecomesself-perpetuating.

Subsequent Developmentof Political Theory:Empirical and

theoreticalstudies that followedthe Weber-Michelsmodel of

organizationelaboratedit along threemain lines - an explica-

tion of the sources, dynamics,and consequences of the "iron

law"; an empiricaltestingof the model; and "an examinationof

contingentcircumstancesin which the iron law does not take

hold or when it is reversed"[Osterman,2006, p. 622]. The third

line is particularlysignificantbecause it amends the models

universalityby arguingthatthe adventof oligarchyis not inevi-

table,as Michels claimed,but contingenton a particularset of

conditions.

The case for the contingentnature of oligarchywas per-

suasivelypresentedby Zald and Ash [1966, pp. 328, 340], who

criticizedthe Weber-Michelsmodel as ignoringenvironmental

factorssurroundingorganizationsand insistedthat"theWeber-

Michels model can be subsumed under a more general ap-

proach...which specifiesthe conditionunder which alternative

transformation processes take place." They examined various

conditionalterms,bothinternaland external(includinginterac-

tion withotherorganizations),and concluded that thereis no

evidenceconfirming theinevitableadventofoligarchy.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

The argumentof Zald and Ash [1966] encouragedsubse-

quent empiricalstudies of the contingentnature of oligarchy.

Jenkins[1977, p. 570], drawingon the resultsof Edelsteinand

Warner[1976] and Rothschild- Whitt[1976], argued that the

advent of oligarchydepends upon such factorsas absence of

influentialfactions,weak proceduralguaranteesin competitive

elections,and differences in ideologicalcommitmentsbetween

elite and generalmembers.Otherstudiesidentify the following

additionalconditionsthatinfluencewhetheroligarchyemerges

- characteristics and social statusof theorganization'smembers

et

[Lipset al., 1956; Clemens,1993], decision-making structure,

characteristicsof the leadership,and age of the organization

[Staggenborg,1988; Minkoff, 1999].

Germaneto this study,the question of how organizations

can reverseor breakaway froman oligarchicsituationhas also

been activelyresearched[Osterman,2006, p. 625]. Voss and

Sherman[2000, p. 304] examinedthe revitalizationprocess of

theAmericanlabor movementthathad suffered "theentrenched

leadership and conservativetransformationassociated with

Michelss iron law of oligarchy,"while Isaac and Christiansen

[2002] depictedthe process of how workplacelabor militancy

was revitalized by civil rights movement insurgencies and

organization.The most widelyrecognizedphenomenoncaused

byoligarchyis loss ofcommitment and energyon thepartofthe

membership, whichZald and Ash [1966, p. 334] called "becalm-

ing."Pivenand Cloward[1977] describedhow membership's en-

ergyis lost when an organizationfora poor peoples' movement

becomes bureaucratized,while Voss and Sherman [2000] re-

vealed thatthedeclineof thelabor union movementwas caused

by the loss of membershipcommitment.In the contextof the

labor union movement,Voss and Sherman[2000, pp. 304-305,

309] identifiedthreepre-conditionsfor overcomingoligarchic

symptomsand restoringorganizationalvitality:

First,some local unions experiencedan internalpo-

litical crisis that fosteredthe entryof new leadership,

either through international union interventionor

local elections.Second, these new leaders had activist

experiencein othersocial movements,whichled them

to interpretlabor's decline as a mandate to organize

and gave themthe skillsand vision to implementnew

organizingprogramsusing disruptivetactics. Finally,

international unionswithleaderscommittedto organiz-

ing in new ways facilitatedthe entryof these activists

into locals and providedlocals withthe resourcesand

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 9

legitimacyto make change that facilitatedthe process

oforganizationaltransformation.

Voss and Sherman furthersuggestpotentialfor theirfindings

to be applicable to otherorganizationsby statingthatthe fac-

torsidentified"providea usefultemplatewithwhichto examine

otherinstitutionalized organizationsthat innovatein a radical

directionor failto do so."4AmongthefactorsVoss and Sherman

politicalcrisiswithinthe organization5

identified, and an influx

of new leaders to wield influence,are of importanceto this

study.

We can thereforeconclude that the politicaltheoryof or-

ganizationis a promisingbasis for analyzingthe problematic

leadershipof the ICAEW because the theorypostulatesthatall

leaderships have the potential to become oligarchic as they

grow;the theoryis applicable to voluntaryassociationssuch as

professionalbodies; the theorysuggeststhattheleadershipsde-

termination to maintaincontrolcauses themto pursue policies

thatare in theirinterestsratherthanthoseof the generalmem-

bership;and growthin size and the developmentof organiza-

tional structureslimitthe members'power to influence/control

the leadership.But the theoryalso acknowledgesthe factthat

oligarchyis notinevitable;it dependson internalconditionsand

can be overcomein appropriateenvironmental circumstances.

CONSTRUCTINGA DEMOCRATICALLYELECTED COUNCIL

The organizationalstructureof the ICAEW consistsof the

Council and a varietyof sub-systemswhich include districtso-

cietiesand numerousCouncil-appointed committees.The Royal

Charter(1880) gave Council responsibilityforthe management

and superintendence of theInstitute

s affairsand, as "thepolicy-

makingbody,"it has reignedovertheICAEW throughout its his-

tory.Giventhe purposeof thispaper,it is necessaryto consider

whetherthe ICAEW'sinternalregulationsmatchthe theoretical

characteristics

ofa democraticallycreatedorganization.

Accordingto Merton[1966, pp. 1057-1058],"The democrat-

ic organizationprovidesforan inclusiveelectorateof members

4Voss and Sherman[2000, p. 345] added that"theelementsof crisis,new

leaderswithnovelinterpretations,

and centralizedpressureare likelyto be key."

5Vossand Sherman[2000,pp. 327,343] identifieddisastrousstrikesand mis-

managementof the local union as examplesof politicalcrisesand concluded:

"Thesecriseswereimportant primarilybecause theyresultedin a changein lead-

ership"and that"radicalchangesnecessitatenewleadership."

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10 HistoriansJournal,

Accounting December2008

andforregularly scheduledelections." Mertonadds:"Thedemo-

craticorganization mustprovideforinitiatives ofpolicytocome

fromelectedrepresentatives andtobe evaluatedbythemember-

shipthrough recurrent electionsofrepresentatives." Thus,

In one formor another, a democracy mustprovidefor

a legislative

body:a Congress, a Parliament, or a House

of Delegates...

It is, therefore,all the moreimportant

thata voluntary associationslegislativebody,which

usuallyrepresents thenear-ultimate authorityoftheas-

sociation,be representative ofthediverseinterests and

valuesoftheentiremembership.

TheICAEWsRoyalCharter provided thatthepowerofthe

Councilshouldbe subjectto thecontroland regulation ofspe-

cial and annualgeneralmeetings (AGMs). The originalby-laws

provided fortheCouncilto consistof45 members ofwhomthe

ninelongestserving wererequiredto retireeachyearand were

eligibleforre-election.Fillinga vacancyon theCouncilrequired

formalapprovalat an AGM.Provision was madeforadditional

candidatesto be nominated in writing bytenmembers. In the

eventof a vacancyoccurring betweenAGMs,theCouncilwas

empowered to appointa replacement whowouldretireand be

eligible forre-electionon the same date as thepersonreplaced.

At meetingsof the ICAEW,membershad equal votingrights

and,therefore, wereable to maketheirvoicesheardand views

reflected in theorganization s affairs,

eitherdirectly through the

approvalofmajordecisions taken by the Council (e.g.,propos-

als to reform theby-laws)or indirectly through theelectionsof

councilors.

CRITICISMOF LEADERSHIPARRANGEMENTS

The previoussectionrevealsthatthe policyformulation

and decision-making criteria

fora democratically runorganiza-

tionwereformally in thecase oftheICAEW,and one

satisfied

mighttherefore expectthelegislative body,the Council,to be

of

"representative the diverseinterestsand valuesoftheentire

membership" [Merton, 1966, p. 1058].In practice,theCouncil

was,fromveryearlyon,judgedbyboththemembership andthe

accounting pressto consist insteadof self-perpetuatingelites.

Therewerefourinter-related elementsin thecriticism of how

theICAEWs leadership was constituted in practice- over-repre-

sentationofleadingfirms, unbalancedgeographical representa-

tion,biasedre-election

arrangements, andnon-representation of

businessmembers.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 11

Over-Representation ofLeadingFirms:The ICAEWs firstCouncil

includedfivecases of two memberscoming froma single ac-

countingfirm.6 ApartfromThomas,Wade, Guthrie& Co., these

wereall Londonpartnerships. The authoroftheICAEWs official

history, himselfa formerpresident,recordsthatcriticismofthis

featureof the Councils compositionwas aired earlyon [Howitt,

1966,p. 28]:

It was advancedthattheaffairsoftheInstitutewerebe-

ing handledby too small and privilegeda circle,and at

the second Annual General Meetingin 1883 a motion

was proposedto preventany firmof accountantsfrom

being representedby more than one memberon the

Council...The questionremaineda contentiousone.

The Councils response was that this arrangementhad been

given "the most grave consideration...at the foundationof the

Institute"[Accountant, May 5, 1883,p. 13] but allowed to stand.

Indeed, it had been createdbecause of the desire to presenta

strongpublic profile.Accordingto councilor CF. Kemp, cit-

ing the example of representationsmade to the government

concerningthe BankruptcyBill 1883, "itwas necessaryto bring

the greatestpossible influencetheycould obtain to bear,and...

withoutthe recognisednames which theypossessed they[the

ICAEW] would notbe in thepositionwhichtheynow occupied"

[Accountant, May 5, 1883, p. 11]. However,to preventany fur-

therextensionof the representation of leadingfirms,it became

an "unwrittenrule" that "not more than two partnersin the

same firmshouldserveon the Councilat the same time"[Coun-

cil MinuteBook Y,p. 4; File 1490].7

GeographicalRepresentation:The ICAEW was originallyformed

fromthe amalgamationof fivesocieties,of which fourprimar-

ily catered forpublic accountantsworkingin the cities where

theywere formed- Liverpool,London, Manchester,and Shef-

6E. Guthrieand C.H. WadefromThomas,Wade,Guthrie& Co.; R.P.Harding

and F. WhinneyfromHarding,Whinney& Co.; A.C.Harperand E.N. Harperfrom

E. NortonHarper& Sons; W. Turquandand J.YoungfromTurquand,Youngs&

Co.; and W.W.Deloitteand J.G.Griffiths

fromDeloitte,Dever,Griffiths

& Co.

7This rulewas abandonedin 1966 because "itcould

prohibitmemberswho

couldgivevaluableserviceto theInstituteas membersoftheCouncilfrombeing

appointedtotheCouncil"[CouncilMinuteBookY,p. 42]. Fromthatdate,Council

adopteda "ruleof guidance"that"notmorethanthreemembersin directpart-

nershiprelationshipmayserveconcurrently as membersoftheCouncil"[Council

MinuteBook Z, p. 92].

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12 HistoriansJournal,

Accounting December2008

field.Theinaugural 45 Councilseatswere,withtwoexceptions,8

allocatedbetweenthe foundingassociations[Howitt,1966,

p. 24]9and, therefore, wereinevitably heavilybiased in favor

of thosegeographical areas. The geographical distributionof

Councilmembership was questioned at the very AGM

first held

on June7, 1882,whenA. Murray suggested that"Suchtownsas

Newcastle andBristolshouldbe represented" [Accountant,June

10, 1882,p. 10]. G.B. Monkhouse, Newcastleupon Tyne,and

E.G. Clarke,Bristol,wereappointedto the Councillaterthat

year,and the 1883AGMwas informed thatCouncilhad been

"strengthened" by the electionof these"eminentaccountants

fromdistricts hitherto unrepresented" [Accountant, May5, 1883,

p. 13].

The ICAEW'sleadershipdid notimmediately embraceen-

thusiasticallythenotionofgeographical equality,however,with

the GeneralPurposesCommittee (GPC) decidingin July1888

that"itis notdesirabletogo intostatistics ofmembership witha

viewto redistribution ofthemembers oftheCouncilamongthe

variousdistricts in proportion to themembersof theInstitute

residingin those districts"[Ms.28416/1, p. 97].Within a decade,

we detecta softening oftheGPCs stancewhenrecommending

in October1897 thatsouthWalesbe represented forthefirst

timeon theCouncilthrough theappointment of R.G. Cawker

[Ms.28416/2, pp. 10,15].Councilagainremained unmoved, but

gradually to for

responded pressure provincial representationso

that,by 1901, a revised quotasystem had been Of

instituted. the

45 availableplaces,12 wereallocatedto thefourexisting socie-

ties (Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, and Northern) and

a further to

eight major cities.The 25

remaining places were

reserved forLondonmembers.

The openingmoveto improvefurther provincialrepresen-

tationoccurredat the 1901AGMwhenW.R.HamiltonofNot-

tingham complained of"theover-representation ofLondon"and

requested the Council to take stepsdesigned achieverepre-

to

sentation on theCouncil"insomemeasurecorresponding tothe

[geographical] distribution ofaccountants" [Accountant,May4,

1901,pp. 534-535]. This plea met with a stonewalling response

8Througheffectivepoliticalmanoeuvring [Walker,2004,chapter11],Edwin

Guthrieand CharlesHenryWade,who belongedto none of thefivemergingin-

werenot onlyadmittedas foundermembersbut werealso allocated

stitutions,

seatson theCouncil.

9Of45 Councilseats,20 wereallocatedto theInstituteorAccountants, 14 to

theSocietyofAccountants, threeto theManchesterInstitute(in additiontoWade

and Guthrie),and threeeach to theLiverpoolSocietyand theSheffield Institute.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 13

fromErnestCooper,president1899-1901,who insistedthat"all

they[the Council] desiredwas the best possible process of get-

tingthe best possible men on the Council"[Accountant, May 4,

1901,p. 536], furtherexplainingthatthe role of the quota sys-

temwas to helpmaintain"a fairproportionbetweenthecountry

membersand the London members."If,instead,the matterwas

leftto the generalbody of members,Cooper believedthat the

inevitableresultwould be "to elect farmore London men than

at present,because the great body would be in London" [Ac-

countant,May 4, 1901,pp. 536-537].10

Continued and persistent complaints from provincial

memberseventuallyproducedpositiveresults,withthe grantof

Councilrepresentation oftenappearingto followas a rewardfor

forminga local society.11A widerdegreeof provincialmembers'

representationon Council was thereforeachieved,withthe se-

lectionof membersbeing made by the Council based on nomi-

nationsfromprovincialsocieties.However,widerrepresentation

fortheprovincesdid not necessarilymean increasedrepresenta-

tion.By 1950, 13 provincialsocietieshad been created,and the

numberof Councilmembersassignedto themwas 2 1, onlyone

seat morethanthe 1901 allocation.The majority(24) of Council

seats continuedto be assignedto London members.

Re-electionArrangements: There were a numberof featuresof

the re-electionarrangementswhich were thoughtto have per-

petuatedcontrolby elites on the Council and to have made it

difficult

to counteritsbiased compositionbothin termsofgeog-

raphy and thefavoritism accordedtheleadingfirms.

Those retiring by rotation wereroutinelyre-elected,causing

a contributor to TheAccountantto complainthat"theCouncilis

notrepresentative as it shouldbe by theBye-lawsofthe Charter.

For the last nineteenyears (I thinkwithouta singleexception)

the Council have re-electedthemselves!"[Accountant,June 9,

1900, p. 533]. Criticismswere also directed,persistentlyand

vehemently, at the practiceof the Council fillingvacancies that

arose betweenannual meetings,an actionwhich,it was felt,de-

10The dissatisfaction

among Nottinghammemberswas settledin 1907,

whenT.G. Mellorsof Mellors,Basden & Mellors,Nottingham was appointedto

theCouncil.TheAccountant[December14, 1907,p. 726] reportedthat"Theap-

pointment is an excellentone in everyway;but perhapsespeciallyso because it

removesa grievanceunderwhichNottingham has been sufferingforsome years

past."

11

Nottingham(1907), South Wales (1913), Leicester(1930), South Eastern

Society(1939),East AnglianSociety(1939)

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

privedthe membershipfromhavingits say at the nextAGM: "If

a councillordies or retiresa Mr.Brownor a Mr.Jonesis given

the situation,and the memberswho annuallyretireby rotation

are re-electednem. con" [Accountant,June 9, 1900, p. 533].12

The issue was raised at the 1901 AGM when Hamiltonreferred

"totheveryold grievanceofthefilling-up ofvacanciesoccurring

in the Councilduringtheyearby the Council,insteadof leaving

those vacancies to be filledup by the members"[Accountant,

May 4, 1901, p. 534]. Proposals that casual vacancies should

be leftunfilleduntilthe nextAGM, made at Council meetings

by such luminariesas FrederickWhinneyin 1882 and George

WalterKnox in 1885,metwithno success [Ms.28411/1,pp. 167,

402; see also, Ms.28411/2,p. 300; Ms.28416/1,p. 97]. Indeed,on

October 14, 1896, Council explicitlyresolved"not to make any

departurefromthe existingpractice"of fillingcasual vacancies

[Ms.28411/4, p. 115].

It could well be argued thatthe membersliterallyhad the

solutionin theirown hands, but thattheyfailedto exerciseit.

A supplementary reportof the GPC, dated February26, 1919,

statedthat"therehas been no noticenominatingcandidatesin

oppositionto retiringmembersof the Council for the last 32

years"[Ms.28435/1 6]. Nor has our examinationof the available

archivaldata revealeda singleinstanceofretirement by rotation

leading to a change in Council membership.The Accountant

[May 5, 1894, p. 408] makes the reasonable point that it was

"a veryinvidioustask for the ordinarymembersto object to

persons who had once been elected." But members'inaction

enabled the Council to respondto criticismas follows:"On one

occasion a votewas taken,so thattherulesofproceduredid not

preventthe introduction of anybody;13or at any ratethe testing

ofthefeelingofthemembersin regardto anypersonwho might

be put forward"[Accountant, May 5, 1894,p. 408; see also, May

9, 1896,p. 396].14

The issue of Council controlover new appointmentsalso

had a moregeneraldimension.Whena memberof a provincial

12Seealso, Accountant, May 13, 1893,p. 453; May 5, 1894,p. 408; May 12,

1894,p. 423; May 12,1894,pp. 424-425;December21, 1895,p. 1031;May9, 1896,

p. 396; June23, 1900,p. 573; March18, 1901,p. 327.

13Thisjustification

was somewhatdisingenuousgiventhatthevotetookplace

onlybecause ofCouncil'sfailure,due to an oversight,to filla vacancycreatedby

a memberssuddenresignation.

14The case referred to was probablythe onlyinstancewe have foundof an

electiontakingplace, resultingin the appointmentto Councilof F.H. Collison,

London,in May 1887[Accountant, May2, 1887,p. 271].

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 15

societyretired,the societyhad the rightto put forwardnomina-

tionsforhis replacement,but the Councilreservedthepowerto

choose betweenthe nominees.The positionwas even worse in

London wherethe appointmentremainedentirelyin the hands

of the London Council members.The autocraticnatureof this

prerogativeis furtherunderlinedby the fact that the London

membersof the Councilmaintained,from1899 onwards,"wait-

inglists"ofprospectivecouncilors"in orderto ensurecontinuity

in theworkof the Counciland themaintenanceof its traditions"

[Ms.28435/1 6, emphasisadded].

It was mainlyto address this lattersituationthat,in July

1920, a group of youngerLondon members pressed for the

creationof "a Societyof CharteredAccountantsforLondon on

lines similarto the existingProvincialSocieties...to act together

in a corporatecapacityupon questionswhicharise fromtimeto

timeaffecting the interestsof the profession"[Accountant, July

17, 1920,p. 58; see also, Loft,1990,p. 39]. To appear to respond

positivelyto the London members'concerns,the Council estab-

lished insteadthe London Members'Committee.This arrange-

mentfailedto satisfythe London members'principalaspiration

whichwas to achieve"theprivilege," in commonwithprovincial

societies,of "nominatingmen to fillvacancies on the Council

as and when such vacancies should arise forLondon men" [Ac-

countant,January29, 1921,pp. 121-122].The London Members'

Committeewas, in the estimationof The Accountant[January

29, 1921, pp. 121-122;see also, London Members'Committee

MinutesBook A, p. 4], designedonly to facilitatesocial inter-

courseamongLondon members.

It was to be a further21 years (1942) beforethe anomaly

was addressedand, eventhen,theLondon Members'Committee

(by this time called the London & DistrictSociety)was autho-

rized to make nominationsto Council forfillinga vacancyonly

afterconsultationwith the London membersof the Council.

The survivingrecords of recommendationsmade by London

councilors and the nominationssubsequentlytransmittedto

the Councilby the committeeof the London & DistrictSociety

prove fairlyconclusivelythat the views of London councilors

dominatedthe appointmentprocess [London Members' Com-

mitteeMinutesBooks B, p. 188; C, pp. 7, 108, 177, 200, 245,

263; London & DistrictSocietyMinutesBooks D, pp. 74, 155,

158; E, p. 3].

A final objectionable featureof re-electionarrangements

was the subjectof a leadingarticlein The Accountant[May 21,

1904,p. 669; see also, Accountant,July9, 1904,p. 41]: "Council

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

by a sortof 'apostolicsuccession'fromthe origi-

...hold office...

nal FathersoftheInstitute,and in no realsense have thegeneral

bodyof membershad a voice in eithertheirnominationor elec-

tion."Apostolicsuccession meant that councilors,on death or

resignation,would be replacedby anotherpartnerin the same

firm,and this sometimeswould literallyinvolvea son succeed-

ing his fatherin thatrole. For example,in 1897,when Council

rejectedthe request for south Wales representation, it instead

appointed E. Edmonds in place of W. Edmonds of Portsmouth.

Personal correspondence,dated November29, 1925 fromJ. B.

Woodthorpeto Sir William Henry Peat, a London councilor,

concerningthe deathof JohnWilliamWoodthorpe,also demon-

stratesthisversionof apostolic succession: "I believe thereare

severalprecedentsof a son succeedinghis fatheron the Council,

and, if this should happen in the presentcase, I should esteem

it was a verygreat honour" [Ms.28435/16].More oftenthere

would be no familyconnection,witha prominentexamplefrom

this genreoccurringwhen Samuel Lowell Price was succeeded

by his founderpartnerEdwin Waterhousein 1887. Overall,we

can thereforeconclude that in 1942 and beyond,the Council

retained,substantively,thecharacterofa self-elected body.

A finalfeatureof the non-representativecompositionof the

Councilconcernsthe completeexclusionthroughout the first60

or so yearsoftheICAEWs historyofanyrepresentation whatso-

everofbusinessmembers.It is to thisissue thatwe now turn.

BusinessMembers:At the 1919 AGM, MarkWebsterJenkinson,

a London practitioner,arguedthat"thereis a verystrongfeeling

among the members, amongthe youngermembers,

particularly

that some more progressivepolicy on the part of the Institute

itselfis necessary"[Accountant,May 10, 1919, pp. 398-399].15

As the resultof his workas controllerof factoryaudit and costs

at the Ministryof MunitionsduringWorld War I, Jenkinson

had reached the conclusion that cost accountingwas an area

of growingimportance,that charteredaccountantsknew less

than theyshould about it and that,if theyfailedto "deliverthe

goods," a new professionwould springup to fillthe vacuum

[Accountant, January18, 1919,p. 46]. Jenkinson s wide-ranging

i5TheAccountant [January 25, 1919,p. 54] reportedon Jenkinson's

proposals

as follows:"therecan...be verylittledoubtthattheywill meetwithverywide-

spreadsupportamongthemembersoftheInstitute, theyounger

and particularly

members,especiallywhen put forwardby so undoubtablea championof the

youngergeneration'srightsas Mr.WebsterJenkinson."

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 17

proposals forreformincluded a systemof proportionalrepre-

sentationto ensurefairtreatmentof each geographicaldistrict

and, significantly, in lightof his deep-seatedconcernabout the

appropriatefuturedirectionof the Institute,three councilors

drawnfromthe non-practicing membership[Accountant, Janu-

ary25, 1919,p. 54; Ms.28448].

FrederickJohnYoung,president1917-1919,respondedby

creatinga committeeto considerthe subject consistingof ten

membersof the Council,nine representatives fromeach of the

provincialsocieties,and two otherLondon membersof the In-

stitute[Accountant, May 10, 1919,p. 398]. A confidential letter,

dated April3, 1919, fromR.H. March, a Cardiffcouncilor,to

George Colville,secretaryof the ICAEW, reveals that the Spe-

cial Committeewas formedprincipallyto pacifydissatisfaction

amongmembers[Ms.28448]:

the Councilshould not oppose any wisheswhichmight

be put forwardby the generalbodyof membersforthe

considerationof this subject,and should be willingto

listento any suggestionswhichmaybe put forwardfor

the welfareof the profession... if a littletact is shown

now it may have the effectof preventingany show of

irritationor temperat theAnnualMeeting.

Giventhese sentimentsand Council'sdominationof the inves-

tigatingcommittee,it is unsurprisingthat its reportmade no

provisionfornon-practitioner representation on the Council. It

did put forwardcertainrecommendations, one of which might

have provedsignificant in addressingJenkinson s concerns[Ac-

countant,February7, 1920,p. 152; Ms.28448]:

(E) That the presentprocedureof the Council under

which the ProvincialSocieties are consultedwith re-

gardto thefillingof casual vacancies ofthe Councilun-

der Bye-law10 be continuedwhen such vacancyarises,

and thatas faras maybe the representation of the Pro-

vincialSocietieson theCouncilshouldbe proportionate

to thetotalmembershipin Englandand Wales.

The Council endorsedthe otherrecommendationswithout

qualification,but specificallyemphasizedthat"Thepresentpro-

cedureas definedby the Committeeunder'E' will be continued

by the Council"[Accountant, February7, 1920,p. 152,emphasis

added)Ms.28448].

The issue of business members'representationresurfaced

as the numbersemployedin industryand commercebecame

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

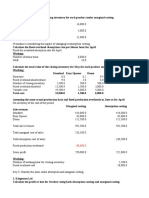

moresubstantial.Table 1 revealsthataroundthetimeofJenkin-

sons intervention on behalfof businessmembers,just 5% (191

of 3,797) of the traceablemembershipworkedin business.The

position then changed dramatically.The number of business

membersroughlytrebledin both the 1920s and 1930s and ac-

countedfor17.2% (1,612 of 9,349) of the traceablemembership

in Englandand Wales in 1939.

TABLE 1

Categorized Membership of the ICAEW in

England and Wales in Selected Years

Members 01/09/192931/10/1939

31/08/1920 01/12/1956

09/11/1946

Publicaccountants 3,606 5,755 7,737 6,840 9,161

Businessaccountants 191 518 1,612 2,493 4,337

Totaltraceable 3,797 6,273 9,349 9,333 13,498

Nottraceable16 995 1,444 2,838 2,854 3,409

Retired - : : : 415

Total 4,792 7,717 12,187 12,187 17,322

Source:MembershipListsfor1921,1930,1940,1947,1957.

E.M. Taylorwho, like Jenkinson, had stressedthe growing

importance of cost accounting in the aftermath of WorldWar I

[Accountant, June 19, 1920,p. 712], presented the 1941 AGM

to

the following resolution designed to address the absence of

representation of the risingnumberof business members[Ms.

28432/19,emphasisadded]:

In the interestsof the whole membershipof the Insti-

tute,it is desirable that the Council shall include not

less thanfiveAssociates,whether practisingmembersor

not,and thatthe membersof the Councilbe invitedto

lay beforethenextAnnualGeneralMeetingoftheInsti-

tuteproposalsto giveeffectto thispolicy.

The Council instead introducedreformsthat failed to ad-

dress directlythe matterat issue. C.J.G. Palmour,president

1938-1944,informedthe 1942 AGM that non-practicing mem-

bers could "best servethe interestsof those by whom theyare

16Membersforwhomthe listingscontain,at best,privateaddressesare in-

cludedinthe"Nottraceable"category. Thenumbersof"Retired" membersare not

separatelyidentifiedbetween1920 and 1946 and, accordingly, are also included

in "Nottraceable"category. The proportionof "Nottraceable,"whencompared

withtheothercategories,is stableat around21.7%. Thus,thetrendrevealedby

is consideredto be a reasonablyreliableindicationoftheincreasein

thestatistics

numberofbusinessmembers.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,I CAEWLeadership 19

employedand the countrygenerallyin takingan active part

in those [technical]spheresratherthan in attemptingto apply

theirmindsto mattersaffecting theadministration ofthe affairs

of practisingaccountants"[Accountant,May 30, 1942, p. 303].

The outcomewas the formationof the path-breaking Taxation

and Financial RelationsCommittee[Zeff,1972,p. 8] to investi-

gate technicalmattersand, throughits mixedmembership,"es-

tablishan activeand effective liaison betweenthepractisingand

non-practising sides oftheprofession"[Ms.28432/1 9].

The Council'ssuccess in again sideliningthe representation

issue, as occurredwiththe formationof the London Members'

Committeein 1920,was short-lived this time.The Councils at-

titudetowardsthe representation of business memberswas at

last softening,possiblybecause of the rapidlyrisingproportion

of business members,and perhaps in recognitionof business

members'valuable contributionsto the work of the Taxation

and FinancialRelationsCommittee.Between1943 and 1948,the

London and Manchesterdistrictsocietiessuccessfullynominat-

ed fourbusinessmembersforpositionson theCouncil.The situ-

ation was extendedand formalizedat the 1950 AGM when the

president,RussellKettleof Deloittes,announcedthe creationof

a pool of up to fiveCouncil seats17exclusivelyavailable to non-

practicingmembers.But he also reaffirmed "theprinciple"that

"havingregard to the objects for which the Royal Charterwas

granted,membership of the Council should as a generalrule be

confinedto practisingmembers"[Accountant, May 13, 1950,pp.

541-542].

Continuedpressurefora greatervoice forbusiness mem-

bers bore furtherfruitthroughthe formationof a GPC Sub-

Committee(Non-Practising Members)in 1951 and the Consulta-

tiveCommitteeof Membersin Commerceand Industryin 1957

to considermattersrelatingto the interestsof business mem-

bers [GPC MinutesBook J,p. 180] and to convey"broad and

exclusivelynon-practising opinionheld by personsof eminence

in industryand commerce"[GPC MinutesBook M, p. 175]. In

the view of business memberssuch as J. Clayton,however,the

formation ofsuch a committeewas notthemosteffective means

for improvingthe representationof the interestof business

members.He argued[File 5-8-14]that:

what was needed was proper integrationof the two

[practisingand non-practising] sides of the profession

18As a consequence,thequota allocatedto provincialsocietieswas reduced

from21 to 19 and Londonfrom24 to 2 1.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

and this could only be done by opening the Council

to more non-practisingmembers. Industrial opinion

would thenbe properlyassimilatedat all levels and in

all Committees.

The ConsultativeCommitteeof Membersin Commerceand

Industryresolvedin October1962 thatthe GPC shouldbe asked

to supportan increase in the size of the Council from45 to

60, with 15 seats to be allocated to membersin commerceand

industry[GPC MinutesBook R, p. 137]. Also, to help achieve

"therightbalance of soundjudgmentand experienceon the one

hand and special skillsnecessaryto conductthe wide range of

its workon the other"[GPC MinutesBook R, pp. 135-136],GPC

recommendedthe introduction of a systemof co-optionofup to

six additionalmembersas "a reserveto be filledat the absolute

discretionof the Council" [GPC MinutesBook S, p. 60]. These

proposals were approved by a special general meetingof the

ICAEW membershipheld on September23, 1965 [CouncilMin-

utes Book W, p. 154]. As a resultof seat re-allocations,the bal-

ance betweenpractitioners in London and theprovincesfavored

the latterforthe firsttimein the historyof the ICAEW,24 seats

comparedwith2 1.

The above four inter-relatedcriticisms,sustained over

the period 1880-1970and directedat the Councils lack of fair

representationof the membership,raise serious doubts over

whetherthe democratic leadership arrangementscontained

in the ICAEWs internalregulationswere effectivein practice.

Certainly,manymembersthoughtthe Councilwas notrepresen-

tativeof the diverseinterestsof the membership, but were their

criticismsjustified?The nextsub-sectionaddressesthisissue in

threeways;namely,by examiningthe geographicalallocationof

council seats in relationto membershiplevels,the distribution

ofcouncilseats in relationto thesize and locationofaccounting

firms,and the divisionof seats betweenaccountantsworkingin

publicpracticeand in business.

Analysisof Distributionof CouncilSeats: Over the period 1880-

1970, 308 individuals,includingthe foundercouncilors,were

appointed to the Council [Ms.2841 1/1-14;Council Minutes

Books O-AB],of whom 29 were membersin industryand ten,

including two furtherbusiness accountants, were recruited

whenthe SocietyofIncorporatedAccountantsand Auditorswas

absorbedintothethreecharteredinstitutes in 1957.The remain-

ing269 werepracticingmembers.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 21

Numericalinformation concerningthe membershipof each

of the main districtsocietiesand the numberof Council seats

allocatedto the geographicalareas thattheycoveredat fivedif-

ferentdatesbetween1907 and 1956 is givenin Table 2. It reveals

thatLondon memberswereconsistently over-represented on the

Council,based on theirshare of totalU.K. membershipin com-

parisonwithmost provincialsocietiesat most dates. The over-

representation was greatestin 1907, but still materialin 1956

when each of the otheridentifiedgeographicalareas continued

to be under-represented. As noted above, the numberof seats

allocated to the provincialdistrictsexceeded those forLondon

forthefirsttimein 1965,withtheresultthatLondon'sshare fell

from52.5% to 46.7%. Even then,London membersremained

heavilyover-represented as theircontributiontowardsthe total

U.K. membershiphad declinedto 37.5% by 1972 [Council Min-

utesBook AF,p. 231].18

To studyallegationsthat Council membershipwas domi-

natedby a limitednumberoflarge,long-standing London firms,

we have identified thosewhicheitherhad a memberon the first

Council of the ICAEW or were formed15 years or more prior

to 1880 [Boys, 1994, pp. 17-18, 56-58; see also, Parker,1980,

pp. 36, 39-42;Matthewset al., 1998,pp. 283-322].This exercise

produceda list of 30 London "founder"firms.The numbersof

Council seats occupied by partnersin these firmsand quali-

fiedaccountantsemployedat these firmsat fivedates between

1920 and 1956 are givenin Table 3.19Corresponding figuresalso

appear in Table 3 for "other London firms" and "non-London

firms"in England and Wales. We have applied the chi-square

testto examinethe statisticalsignificance, if any,of the differ-

ence in levelsof Councilrepresentation at each of the fivedates

betweenLondon founderfirmsand the othertwo groups.Atthe

firsttwo studydates (1920 and 1929), the resultswere signifi-

cant at the 5% level,giventhereis onlyone degreeof freedom.

For 1939, the testprovedsignificant at the 10% level. For 1946

and 1956,theresultswere significant at neitherthe 5% nor 10%

18The officially recordedjustification forLondon'spreferment in termsof

Councilseatswas thedistancebetweenmanyprovincialareas and Londonwhere

themeetingsoftheCounciland itscommittees wereheld[CouncilMinutesBook

O, p. 227; File 1487].

19FromtheCompaniesAct 1862 to the

CompaniesAct 1967,thereexisteda

provisionprohibiting, in principle,partnershipsof morethan20 members.The

numberofqualifiedaccountantsemployedin accountancyfirms, ratherthanthe

numberofpartners, is thereforeconsideredto be a betterindicationofthesize of

theaccountancyfirm.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

i1: ft tu m tü a m fD £i ft p:

^ £T g £T g BTS BTS BTS

U>

io - 0s <*> n>

- ^ £

^ w aP dd

& S^ ^^ So 3'

I

et

^

rt *-* ^ ö *»j -^ '--i bo '-g 4^. '-J ^ £

« nOnO nOnO nDnO vOnÖ ^vO°3 ^

c^c^c^ ö^o^ ö^ö^ ö^o^ ö^q^

tr

C <l O Ji. K) h- m fi

C/5 OOK) LnK) OK) K)K) i- ' K) S f^

r-th- h- ve o oo y &

8 w ö

S,

>-' Ln ui Ln^ Ln^ çn^ U)^ p^*

ö

I

<l^^ ö^ö^ c^ö^ ö^ö^ ö^ö^ §^

UI O

?

"^"-j Qn Ln u> h-32-

U)K) VOU» LnU) OU» -^J U> o t- i ft

>-* O U» O On • L. ff.

I

fi 8

LnLn ui a ^JC> ^JOn LnON g

!t^ Ö '-J '"^4 k) '--J U) '-vj h ^ ^ S-

cy^cS^ (^(S^- cS^cS^ <$^<$^ o^cy-

r

-T" i* 00 Ln u> 3 h^

^U> K)^. K)Ln OLn K)LnS&

v/l 00 {jy *^J J^ . Û)

u> Ln g

n

er

5^ 3?° õ£ !3 ^ vo ^ 8

o

i-h

O Ln u> i-» h- O

"¡g KJ

•- '

"u> K) Ln K) 'o ^ It^ N> 5 o

4^. vO"^ (-»On ^».On Qn~^P ' i- i

I

Ln ►- K- oo -t» ^

a

P-

-fc>Ln 4^-Ln 4^-Ln 4^.Ln 4^0 O

onK)

I

.-^^ í^^ 9s r4 î°Pç> 3

UíLn k)U> Ò bo U>òo í-o^

Ö^Ö^ Ö^^ ^-Ö^ Ö^ Ö^ Ö^Ö^

Iu

U> U> 1- h-

Ln K) h- 00 Q

s.

K>K) K)K) tO 1-» N) >-' U>h- 2 Pf

U> K) Ln O K) U» O U> K) h-«■ o

4^ Ln Î-» Ö Kj U> 4^ U> '-^1 i-* ^

Ö^Ö^ i^W^ W^ö^ O^C^ ö^ö^

UJ ^ -^ ^

-ío 3

-I^O

4i.

^Ln

4^ bv

^

-^ K)

^

H-Ln

-^ j^

"°

4^.

' >

*

ts

S 3

u>^" ZjLnO

^^ c^c$^ ^^ ^^ ^^

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 23

levels. Given these significancelevels, it seems reasonable to

concludethat,beforeWorldWar II, London founderfirmswere

continuouslyover-represented on Councilthoughthiseffectwas

diminishing, but thatthiswas no longerthe case afterthewar.20

TABLE 3

ICAEW Membership and Council Seats by Type of Firm

LondonfounderOtherLondon Non-London _ ,

cfirms cfirms c Total

firms

1920 no. % no. % no. % no.

Councilseats 16 35.6% 10 22.2% 19 42.2% 45 100%

ICAEWmembers 148 20.6% 210 29.2% 362 50.3% 720 100%

1929

Councilseats 15 33.3% 11 24.4% 19 42.2% 45 100%

ICAEWmembers 334 18.4% 540 29.8% 937 51.7% 1,811 100%

1939

Councilseats 16 35.6% 8 17.8% 21 46.7% 45 100%

ICAEWmembers 601 23.8% 723 28.6% 1,203 47.6% 2,527 100%

1946

Councilseats 16 35.6% 8 17.8% 21 46.7% 45 100%

ICAEWmembers 406 27.8% 338 23.1% 717 49.1% 1,461 100%

1956

Councilseats 15 37.5% 6 15.0% 19 47.5% 40 100%

ICAEWmembers 681 32.4% 445 21.2% 976 46.4% 2,102 100%

Source:MembershipListsfor1921,1930,1940,1947,1957

To examine furtherthe extentto which councilors were

recruitedby "a sortof 'apostolic succession'"[Accountant, May

21, 1904,p. 669], 60 long-standing provincialfirmswere identi-

fiedthroughthe same procedureused to detectthe 30 London

founderfirms.From the combinedlist of 90 founderfirms,we

were able to calculatethat 157 (58.4%) of the 269 councilorsin

public practiceover the period 1880-1970stemmedfromthose

origins.Even ifwe excludetheoriginal45 members,we findthat

112 (50.0%) of the 224 memberssubsequentlyappointedto the

Council had the founder-firm root. Despite the rule established

in 1883,restrictingto a maximumoftwothenumberofpartners

in the same firmand workingfromthe same principalplace

of business servingon the Council at the same time [Council

MinutesBook Y, p. 4; File 1490], 64 of 112 (57.1%), councilors

20One reason forthis change was that,duringWorldWar II, the London

founder-firm membership fellby only32.5%,whereasthatof otherfirmsfellby

45.2%. Hencetheimbalanceofthepre-warera was resolved,notbya proportion-

ate reductionin the numberof Councilseats forLondon founderfirms,but a

largerfallin membershipamongotherfirms.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

were recruitedfromjust 19 large London firms.21 Moreover,36

ofthe 112 members(32.1%) and 30 ofthe 64 London councilors

(46.9%) were thereas the resultof "apostolicsuccession,"i.e., a

partnerfromthesame firmwas appointedto replacea councilor

who had resigned.

Turningto businessmembers'representation, we have seen

thattheyhad no representation whatsoever on the Counciluntil

1943, and that theyreceivedtheirfirstquota allocation of five

out of45 seats or 11.1% in 1950.We have also seen thatbusiness

membersaccountedfor17.2% oftraceablemembershipas early

as 1939,and we are able to interpolatefromTable 1 a business

membershipof about 30% between 1946 and 1956. Later,in

1964, accordingto an estimatemade by a GPC sub-committee,

"10,000or moremembersof the Institute... are engagedin com-

merce and industry"[GPC Minute Book R, pp. 135-136] at a

timewhen the totalU.K. membershipwas 23,285 [Membership

evenwhen the quota was increasedto 15

List, 1964]. Therefore,

out of 60 in 1965,business memberswere stillseriouslyunder-

represented on theCouncil.

The evidencepresentedin this sectionrevealsthat,consis-

tentwithcriticismsdirectedat the compositionof the Council

by the ICAEWs membersand the press,its non-representative

characterpersistedthroughoutthe period 1880-1970,despitea

seriesofinitiativesdesignedto improvethesituation.

A Self-PerpetuatingOligarchy- theHistoricalDimension:In this

sectionso far,we have studiedchangesmade by the ICAEW in

responseto continuousand vehementcriticismof the self-elect-

ed characteristic of

of the Council and the under-representation

a varietyof sectionalinterests.We have also seen thattwoworld

wars providedimportantopportunitiesto reviewcriticallythe

oligarchicnatureof the Council. WorldWar I made influential

charteredaccountantsaware ofthegrowingimportanceofbusi-

ness accountingwithinthe portfolioof work that constituted

contemporaryprofessionalpractice and encouraged progres-

sive practitioners,such as Mark WebsterJenkinson,to sup-

port claims frombusiness membersforrepresentationon the

Council.WorldWar II, againstthe backgroundof a substantial

21TheseincludedPrice,Waterhouse& Co. (9 councilors);CooperBrothers&

& Co. (6);

Co. (7); Peat,Marwick,Mitchell& Co. (6); Deloitte,Plender,Griffiths

Turquand,Youngs& Co. (5); Whinney, Smith& Whinney(4); Kemp,Chatteris,

Nichols,Sendell& Co. (4); Binder,Hamlyn& Co. (4); Barton,Mayhew& Co. (4);

James& Edwards(3); Josolyne, Miles,Page & Co. (2); HarmoodBanner& Co. (2);

and Cash,Stone& Co. (2).

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 25

increase in business membershipwithinthe ICAEW, encour-

aged people such as E.M. Tayloragain to highlightthe issue of

businessmembers'representation.22 These findingssupportthe

argumentthat"democratization tendsto followwar" [Mitchell,

1999,p. 771].

We have seen that a numberof changes were made that

caused the Councilto become more representative of the mem-

bershipin 1970 than at foundationdate. Despite such changes,

however,we mustconclude thatthe fundamentalnatureof the

Council,as a self-elected

oligarchy,remainedsubstantiallyintact,

with the mechanismsemployedto defend that characteristic

including(1) the quota systemused to allocate Council seats to

London and provincialsocieties; (2) the re-electionof retiring

members;(3) the Councils power to filla vacancy arisingbe-

tweenAGMs;(4) theCouncilspowerto choose betweennomina-

tions put forwardby the provincialsocieties;(5) the Councils

controlovertheconsultationprocesswiththeLondon & District

Society;(6) the creationof "pools" of non-practicingmembers

withCouncilretainingthepowerto choose betweennominations

put forward;and (7) the co-optionof additional"suitable"mem-

bersat theabsolutediscretionoftheCouncil.These mechanisms

compriseoverwhelming evidenceof "weak proceduralguaran-

tees in competitiveelections"highlighted as importantfeatures

ofan oligarchicleadershipbyJenkins[1977,p. 570].

The Councilof the ICAEW also exploitedits commandover

organizationalresources[Lipset et al, 1956; Jenkins,1977, p.

569] in otherways to maintainits traditionalcharacterand to

silence,sideline,or pacifydissatisfactionamong membersover

theirinterestrepresentationon Council. Tactics employedin-

cluded the formationof variousadvisoryand consultativecom-

mitteessuch as theSpecial Committee(1919), theLondon Mem-

bers' Committee(1920), the Taxationand Financial Relations

Committee(1942), the GPC Sub-Committee(Non-Practising

Members)(1951), and the ConsultativeCommitteeof Members

in Commerceand Industry(1957). These placating measures

each playeda role to help to moderatemembers'dissatisfaction

withtheCouncil.

22Taylor,

at the1941AGM,statedthat"I havecome to theconclusionthatre-

formsmusttakeplace in thestructure oftheCouncil...Thereare manyproblems

facingus to-day...

whenthewar is overand hundreds,possiblythousands,ofour

memberscomebackto civillife,and possibly1,500articleclerkswithlittle,ifany,

professionalexperiencecome to takeup businesslife...a broaderrepresentation

on theCouncilis goingto be beneficialto theInstituteas a whole"[Accountant,

May 17, 1941,pp. 376-377].

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26 HistoñansJournal,December2008

Accounting

The oligarchiccharacterof the Councilof theICAEWex-

istedfromtheoutsetandwas mostintensively attacked immedi-

atelyfollowing organizational formation in 1880. Michels [1962,

p. 167] observesthat"Withtheinstitution of leadershipthere

simultaneously begins...thetransformation intoa closedcircle."

Osterman [2006,p. 623],on thissameissue,comments that:

The questionof timing... becomesthepracticalone of

the lengthof timeit takesto createa self-sustaining

bureaucratic apparatusand internalpoliticalsystem.

Putthisway,itis apparent thatthereis no universal an-

swerto thetimingquestion.It dependson thecharac-

teristics oftheorganization in question,suchas size of

membership, geographic scope,history,andso forth.

The historical dimensionis highlysignificant forthiscase

study.We have seen that theICAEW was formed from themerg-

er offiveexisting institutions. Among these,the elitebodywas

theInstitute ofAccountants whichdominated themerger nego-

tiations[Walker, 2004]and also thecomposition oftheICAEW's

initialCouncil[Edwardset al., 2005].TheInstitute ofAccount-

antshad,in 1876,beenaccusedbyitsmembers ofarbitrary and

selective for

procedures appointing councilors which, as in the

case ofKemps justification foran ICAEWCouncilconsisting of

the"greatand thegood"in 1883,was explainedbytheneedfor

a strongpublicprofile [Walker, 2004,p. 142].Thislattertheme

was givenparticular emphasisbyErnestCooperwho,we have

seen, also staunchly defended thecomposition of theICAEWs

Councilwhenpresident in 1901.As a highlyactivememberof

theInstitute ofAccountants in the1870s,Cooperadvocatedre-

formsdirectedtowardsachieving improved recognition forthe

profession in

[cited Walker, 2004,p. 291]:

Can it be doubtedthatiftheInstitute aftertheScotch

Systemwas introduced herehad beenactively engaged

duringthe past sevenyearsin ascertaining who are

therespectable Accountants and inducingthemtojoin

theInstitute thattheprofession wouldhave assumed

a muchhigherpositionin relationto thecontemplated

Bankruptcy reform?

ForCooper,toincreasethenumberof"respectable" accountants

withinthesmallmembership of theeliteInstitute of Account-

antsand to have"thebestpossible men" on the Council ofthe

ICAEWwereprobablyconsistent objectivesin the sense that

bothenhancedtheinfluence in

oftheorganization makingrep-

resentation to thegovernment overthecontent oflegislationre-

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Noguchiand Edwards,ICAEWLeadership 27

latingto theaccountants'business.We mighttherefore conclude

[see also, Walker,2004, p. 139] that the Council of the Institute

in

of Accountants London institutionalizedits characteras a

self-perpetuating eliteduringthe 1870s,an historicalcharacter-

isticinheritedbytheICAEW.

The mostimportantdifference betweenthe real case of the

Council of the ICAEW and oligarchytypicallyenvisagedin the

politicaltheoryof organizationis in motive.In theory, oligarchy

emergesbecause thepositionsoccupiedbyleadersoftheorgani-

zation "providethemwitheconomicrewardsand social status"

[Osterman,2006, p. 623]. However,in the process wherebythe

ICAEW Council initiallyformedand subsequentlymaintained

an oligarchiccharacteristic, evidenceof the councilorsenjoying

directpersonalgains fromtheirpositionsremainsunidentified,

although,as Smallpeice [1944, p. 46] recognized,achievingthe

positionof counciloritselfrepresented"a highhonourforprac-

tisingmembersand is much prized...as a markof esteem and

a rewardforoutstandingservicein the profession/'Aside from

personalmotives,the dominantconcernwhen constructing the

composition of the Council was to maintain and enhance, as

indicatedby Kemp's 1883 comment,the political influenceof

the ICAEW in makingrepresentations to the governmentover,

forexample,the contentof legislationrelatingto its business.

From its experiencewhen acquiringthe Royal Charterin 1880,

the Councilof the ICAEW appears to have assumed thatthe in-

fluenceof councilorsfromthe London foundingfirmswould be

ofcrucialimportanceforthepurposeofmaintainingitspolitical

standing.

Reflectingits oligarchiccharacter,the biased composition

of Council provedhighlysignificant in a negativesense at the

time of the 1970 scheme forintegrating the six senior profes-

sional accountancybodies in Britain.It was memberswho were

eithernot representedor under-represented on the Councilthat

featuredprominently in rejectingtheleadershipsplans. The po-

liticalcrisisis nextexamined.

THE 1970 INTEGRATIONSCHEME

The 1970 mergerplan had been approved by fiveof the

six senior professionalbodies involvedwhen, "virtuallyat the

last moment,a campaign was launched by two membersof

the EnglishInstitute"[Tricker,1983,p. 40]. H.T. Nicholsonand

B.W. Sutherlandcriticizedthe integrationscheme as involving

"an unacceptable dilution of the high professionalstandards

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 12:56:35 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28 HistoriansJournal,December2008

Accounting

of the Institute"[Accountant,July16, 1970, p. 73]. It is widely

acknowledgedthat,principallyas the resultof latentopposition

mobilizedby theirintervention, the integrationschemewas re-

jectedby 16,845 votes against13,700with64.1% oftheICAEWs

membershiptakingpartin thepoll.

For Nicholson and Sutherland,the scheme had been pro-

jected by '"menin a hurry',who refusedto recognizethatsound

developmentcould onlycome by a process of steadyevolution,

and were obsessed with the idea of creatingthe biggestbody

of accountantsin the world"[Accountant, July16, 1970,p. 73].

As faras businessmemberswere concerned,integrationwould

result in "people [becoming] called chartered accountants

who have neverworkedin a professionaloffice"[Accountancy,

September1970, p. 635; see also, File 1477: 17 (34)]. For pro-

vincialpractitioners,integrationwas consideredto produce "an

unacceptabledilution"of status [Accountant,July16, 1970, p.

73; see also, Accountancy,September1970, pp. 635, 637]. And

foryoungermemberswho had recentlysufferedthe traumaof

qualifyingexaminations,integrationwas seen as a retrograde

step thatwould lessen the value of the charteredcredential[Ac-

countancy,June1966,p. 443].

The outcome was described in the ICAEWs mouthpiece,

Accountancy[September1970,p. 637], as "a disasterforthe ac-

countancyprofessionas a whole,and forthe Instituteespecial-

ly,"while The Accountant[August20, 1970, pp. 229-230] made

thefollowingassessmentofevents:

it mighthave been temptingto accuse a fewindividuals,

whose oppositionhas been particularly determinedand

perhapsmore articulatethan most,of havingwrecked

the scheme; but it seems plain that these gentlemen

have done nothingmore than to provide,at the most,

a focusforthe considerablemeasure of dissatisfaction

and dissentwhichalreadyexisted.