Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AUBRY - A Fresh Look at The Contribution

AUBRY - A Fresh Look at The Contribution

Uploaded by

Tatiane OliveiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AUBRY - A Fresh Look at The Contribution

AUBRY - A Fresh Look at The Contribution

Uploaded by

Tatiane OliveiraCopyright:

Available Formats

PAPERS A Fresh Look at the Contribution of

Project Management to Organizational

Performance

Monique Aubry, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montreal, Canada

Brian Hobbs, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montreal, Canada

ABSTRACT ■ INTRODUCTION ■

A better understanding of organizational per- he aim of this article is to enrich the current discussion on the value

formance and the contribution that project

management can make is the aim. The article

adopts the “Competing Values Framework,” a

rich framework that is well established both

theoretically and empirically but is not well

T of project management by presenting empirical results from a

research on the performance of project management offices (PMOs).

It proposes a novel approach to performance inspired by the

Competing Values Framework (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983).

Performance is often identified as the ultimate dependent variable in the

known in the field of project management. The literature on organizations. It is currently the focus of much attention in

framework is summarized and applied in an the project management literature (Thomas & Mullaly, 2008). The current

empirical investigation of the contribution of focus on the topic seems to be driven by the belief that organizations will

project management in general and project adopt project management only if it can be shown to generate value. After

management offices (PMOs) in particular to more than a half-century of history in the management of projects, its con-

organizational performance. The examination of tribution to performance is still not acknowledged outside the group of

11 case studies revealed multiple concurrent professionals who believe in project management. The community of pro-

and sometimes paradoxical perspectives. The fessionals and academics within project management associations are

criteria proposed by the framework have been mostly preaching to the converted. However, outside of this community, the

further developed through the identification of a value of project management is not generally recognized, particularly at sen-

preliminary set of empirically grounded per- ior levels (Thomas, Delisle, Jugdev, & Buckle, 2002).

formance indicators. The empirical results con- A major piece of research on the value of project management led by

tribute to a better understanding of the role of Thomas and Mullaly has recently been completed (Thomas & Mullaly, 2008).

project management generally and PMOs They propose a framework where project management implementation and the

specifically. They also demonstrate the useful- value of project management are aligned within the organizational context

ness of this framework for the study of project through the notion of “fit.” The notion of value has been used to focus on

management’s contribution to organizational what project management is worth to different stakeholders. The level of

performance. analysis is the organization in both Thomas and Mullaly (2008) and the pres-

ent article. A major part of the research presented in this article was realized

KEYWORDS: organizational performance; prior to the publication of papers and the monograph by Thomas and

competing values framework; PMO; value of Mullaly (2008). However, efforts have been made to acknowledge their

project management results.

The empirical work reported in the present article centers around PMOs.

Centering the investigation on the PMO facilitates the empirical study of dif-

ferent means of contributing to organizational performance and different

perceptions of the value of these contributions. In brief, it increases the like-

lihood of producing good results for several reasons. First, organizations that

have PMOs have chosen to centralize several aspects of project management in

and around these organizational entities, making project management more

visible in the organization and easier to study. Studying the role of PMOs is,

Project Management Journal, Vol. 42, No. 1, 3–16 therefore, a practical means for studying project management as it is prac-

© 2010 by the Project Management Institute ticed in these organizations. Second, PMOs are small units that are often

Published online in Wiley Online Library located outside the major organizational units. They are thus in a position to be

(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/pmj.20213 appraised by stakeholders in many other units. This improves the likelihood of

February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 3

A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management

PAPERS

capturing multiple conceptions of their performance by the PMO seems to take significant (Thomas & Mullaly, 2008).

contribution to the performance of the different forms. And it should be distin- The clear demonstration of the direct

organization. Third, research by Hobbs guished from the contribution of proj- influence of project management on

and Aubry (2007) has shown that the ects. The PMO’s contribution is, at least return on investment (ROI) is not easily

legitimacy of PMOs is being challenged potentially, behind the performance of accomplished, as explained by Thomas

in approximately 50% of organizations. each individual project. and Mullaly (2008). In addition, the

The discourse that surrounds PMOs is The context of diversity supports reduction of project management value

thus often charged with tensions that the definition proposed here for organi- exclusively to financial indicators

make differing points of view more vis- zational performance based upon the underestimates major contributions

ible and more easily captured in empir- competing values framework. There are that project management brings to

ical studies. Fourth, Hobbs and Aubry two problems: the first one is to establish organizational success—for example,

(2007) have shown that PMOs fill many a clear definition as to what constitutes innovation (Turner & Keegan, 2004),

different organizational roles. In doing organizational performance, and the process (Winch, 2004), and people

so, they potentially contribute to the second is to propose a realistic and reli- (Thamhain, 2004). Furthermore, the

organization in many different ways, able approach to its measurement. This multifaceted concept of project per-

making the diverse contributions more leads to the research questions: What is formance is acknowledged by several

visible and easier to study. In addition organizational performance in the con- authors (Dietrich & Lehtonen, 2004;

to facilitating the study of the contribu- text of project management and how Shenhar, Dvir, Levy, & Maltz, 2001). The

tion of project management to organi- can it be assessed? balanced scorecard is based on the eco-

zational performance generally, the The next section of the article nomic conception. The balanced score-

PMO is a legitimate object of study in explores the literature on performance. card approach has been proposed to

its own right. This is followed by a presentation of the assess project management perfor-

Organizational performance is a sub- competing values framework, an inte- mance (Norrie & Walker, 2004; Stewart,

jective construct. This construct is subjec- grative model that has the ability to 2001). It has the advantage over the

tive because it exists in the minds of capture the diversity of conceptualiza- traditional economic vision of project

those who are evaluating. The organi- tions of organizational performance performance in encompassing four

zational performance of PMOs will vary found within organizations. Empirical complementary perspectives. However,

depending on who the evaluator is. results will then be presented, which the foundation of this approach rests

Most of these stakeholders belong to illustrate the usefulness of this frame- on ROI. It structures the creation of

different units that have different cul- work. The empirical portion of the arti- value hierarchically with financial value

tures and different values. cle concludes with the presentation of a at the top (Kaplan & Norton, 1996;

A construct is not directly observ- set of practical indicators that provides Savoie & Morin, 2002).

able. In order to evaluate it, the vari- a more concrete representation of orga- The second conception of perfor-

ables that form it must be identified and nizational performance and facilitates mance in the literature on project per-

examined. Justification of the PMO the construction of metrics. Finally, a formance is pragmatic. Several authors

remains a recurring problem in organi- conclusion closes the article. have encompassed the problem of per-

zations, with almost 50% reporting that formance in an approach that seeks to

the existence of their PMO has been Organizational Performance in identify success factors ( Jugdev &

recently questioned (Hobbs & Aubry, the Project Management Müller, 2005). A clarification should be

2007). A PMO would be legitimate if it Literature made here to distinguish between suc-

could convincingly demonstrate its Two conceptions of performance dom- cess factors and success criteria.

contribution to organizational perform- inate the project management litera- Success factors refer to a priori condi-

ance. However, the evaluation of its ture: economic and pragmatic. In the tions that contribute to positive results,

contribution to organizational perform- former, researchers try to demonstrate while success criteria are used to assess

ance is a complex question that may the direct economic contribution of a concrete and measurable result a pos-

have as many variations as the PMO project management to the bottom line teriori (Cooke-Davies, 2002). Cooke-

itself. This highlights the subjective side (Dai & Wells, 2004; Ibbs, Reginato, & Davies (2000, 2004) has examined

of organizational performance. Kwak, 2004). Interestingly, none of the empirical evidence supporting the

PMOs are performing many differ- these researchers have been able to many best practices and success factors

ent functions (Hobbs & Aubry, 2007). Are convincingly demonstrate the econom- found in the literature. He concludes

these different functions regarded with ic value of investment in project man- that most of the contributions have

the same value by different stakehold- agement. The results of the research been based on the opinion of members

ers? The contribution to organizational by Ibbs et al. (2004) are not statistically of the project management community

4 February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

and that only a small number have How to Define Organizational life cycle of the organization or of the

been empirically validated. Based on Performance? unit. There exists simultaneously in the

the empirically validated data, Cooke- The concept of organizational perfor- same organization a variety of contra-

Davies (2004) proposes a set of 12 fac- mance is not new. At the end of the 1950s dictory preferences that this type of

tors related to three distinct ways of and in the early 1960s, sustained efforts definition cannot capture.

looking at performance: project man- were made notably to understand the The second approach to a defini-

agement success (time, cost, quality, success of organizations. This literature tion is based on the identification of

etc.), project success (benefits), and developed in the 1960s and 1970s, and limits/borders, which is a semantic def-

corporate success (processes and deci- after 1980 narrowed down to concepts inition. A semantic definition describes

sions that translate strategy into pro- like quality (Boyne, 2003). Several words the meaning of a term by its similarities

grams and projects). It is noteworthy are used almost as synonyms to organi- (positive semantic definition) or by its

that the success factors are different at zational performance—for example, differences (negative semantic defini-

each level of analysis. Cooke-Davies efficiency, output, productivity, effec- tion) with other terms (Van de Ven,

(2004) argues these three groups are tiveness, health, success, accomplish- 2007). Addressing the question “What is

intimately linked; corporate project ment, and organizational excellence organizational performance?” also

and program practices create the con- (Savoie & Morin, 2002). The concept of comes back to trying to define the

text for individual project and program organizational performance has been scope of the total construct by delimit-

practices. While the research on success adopted in this research because it is ing the components located inside and

factors has identified some conditions more appropriate in the context of outside its borders. Cameron (1981)

in organizational project management organizational project management. discusses this question from two view-

that are associated with performance at Trying to give a clear definition of points: the theoretical borders and the

different levels of analysis, the under- organizational performance is not an empirical borders. Practically speaking,

standing of performance and the a easy task. Attempts made to clarify it by the theoretical borders of organization-

priori conditions that contribute to definition have not led to an acceptable al performance do not exist. No theory

performance remains limited. result. Two alternative approaches are is completely satisfying, and the

There is no consensus on the way to explored: (1) a definition of the concept research undertaken so far is made up

assess either performance or the value by the identification of its characteris- of a collection of individual essays that

of project management. The financial tics and (2) a definition of the concept lack integration (Cameron, 1981). It is

approach alone cannot give a correct by the identification of its limits/ difficult to grasp the construct when

measure of the value of project man- borders. The definition by its character- approaching it theoretically, and still

agement for the organization. Project istics is called a definition of com- today, there is no clear definition of the-

success is a vague approximation and, ponents, where a term (in this case, oretical borders (Savoie & Morin, 2002).

as such, a rather imperfect system for organizational performance) is given in A few authors have tried instead to

measuring results. New approaches are reference to its constituent parts or its define an empirical border. Moreover,

needed in order to extricate ourselves characteristics (Van de Ven, 2007). this inductive approach is appropriate

from what looks like a dead end. Organizational performance has been when there is a high level of complexity,

Organizations are multifaceted, leading approached in the literature using dif- which is the case here (Patton, 2002).

to a variety of perspectives and evalua- ferent sets of characteristics or vari- This being the case, each study has

tion criteria. The international research ables. A first difficulty with this type of been done as in a “silo,” each author

on the value of project management definition is the uniformity of the levels observing in an isolated fashion a par-

draws similar conclusions (Thomas & both conceptual and operational ticular type of organization (Cameron,

Mullaly, 2008). among the characteristics (Cameron & 1981). Therefore, approaching a defini-

Whetten, 1983; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, tion of organizational performance by

What Is Organizational 1983; Van de Ven, 2007). There are other the identification of a border does not

Performance? difficulties with this type of definition. It allow us to determine what is inside the

Performance has its origin in the old is inherently subjective (Cameron, 1981). border, because theoretical research is

French parfournir and is defined today It can be difficult—even impossible—to insufficient and empirical studies are

as “something accomplished” (Merriam- reconcile the multiplicity of points of varied and lack integration.

Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 2007). view from different stakeholders. It can To overcome the problem of defini-

The etymology brings us straight to the be difficult even for individuals to iden- tion, Cameron (1981) suggests that orga-

point: what indeed is accomplished by tify their own preferences for an orga- nizational performance be defined as a

project management, and how should it nization. Preferences change over time, subjective construct anchored in values

be evaluated? in keeping with social values and the and preferences of the stakeholders.

February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 5

A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management

PAPERS

This definition offers significant poten- (Thompson, McGrath, & Whorton, on the values of those who are evaluat-

tial for adaptation to organizational sit- 1981). Rather than imagine a new ing (Cameron, 1986).

uations and offers the possibility of model, Quinn and Rohrbaugh The third dimension (orientation

acknowledging that a variety of per- approached the problem in a highly and purpose) was not often used in

formance evaluation models may exist original way by undertaking research empirical research based on the com-

simultaneously. This construct is also based on criteria already identified by peting values approach, including

coherent with the constructivist per- Campbell (1976, cited in Quinn & research by Cameron and Quinn

spective, which recognizes the exis- Rohrbaugh, 1983). They treated these (1999). In a fashion consistent with this

tence of several competing logics. criteria using a combination of the stream of research, only the structure

In this perspective, organizational Delphi approach and statistical model- dimension (paradox between flexibility

performance is anchored in the values ing with the participation of a group of and control) and the focus dimension

and preferences of the stakeholders. In very reputable researchers on two pan- (paradox between internal and external)

the context of project management in els. The research led to a set of 17 unique have been employed in the present

general and PMOs in particular, stake- criteria grouped into three significant research (see Figure 1).

holders are individuals and groups who dimensions: the structure dimension The research of Quinn and

have a substantial interest in the man- (paradox between flexibility and con- Rohrbaugh (1983) thus led to the for-

agement of the projects of the organiza- trol), the focus dimension (paradox mulation of a framework that presents

tion. The stakeholders could include between internal and external), and the 17 criteria and their dimensions in four

the project governance board, the busi- dimension of purpose and orientation. quadrants, each associated with a spe-

ness unit managers, the customers of These dimensions formed three sets cific preexisting model of organizational

the projects, the users, the PMO man- of values that explicitly expressed the performance: the open system model,

ager, the project portfolio managers, dilemmas or paradoxes present in the human relations model, the internal

the functional managers, project man- organizations. These values are in con- process model, and the rational goals

agers, project controllers, and so on. stant competition in organizations, and model. Sixteen of the seventeen criteria

to succeed, organizations must reach are associated with one of the four

The Competing Values good overall results, without necessari- models, each representing a different

Framework ly seeking a balance. In this context, conception of organizational perfor-

Origin and Development of the organizational performance depends mance. The 17th criterion, output quality,

Competing Values Framework

Organizational performance was the

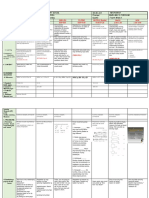

object of a worldwide study for a nucle- Flexibility

us of researchers (Cameron & Whetten,

HUMAN RELATIONS MODEL OPEN SYSTEM MODEL

1983; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983)

toward the end of the 1970s and the

beginning of the 1980s. Quinn and 1. Value of human resources working in project 12. Growth

Rohrbaugh (1983) were, however, the 2. Training and development emphasis 13. Flexibility/adaptation/innovation in project management

3. Moral of project personal 14. Evaluation by external entities (audit, benchmarking, etc.)

first to have proposed the competing 4. Conflict resolution and search for cohesion 15. Links with external environment (PMI, IPMA, etc.)

16. Readiness

values approach. This approach came

out of a research program over a period

of several years at the Institute for 17. OUTPUT QUALITY

Internal External

Government and Policy Studies, intend-

ed to evaluate performance in the pub-

lic sector. This sector is enormously

5. Information mangement and communications 8. Profit

complex, and at a time when the econ- 6. Processes stability 9. Productivity

omy was affected by high inflation, it 7. Control 10. Planning goals

11. Efficiency

was important to ensure the best possi-

ble use of public funds in all public

INTERNAL PROCESS MODEL RATIONAL GOAL MODEL

institutions (Rohrbaugh, 1981).

The theoretical basis of the compet-

ing values approach rests on the fol- Control

lowing assumption: tensions exist in all Note. The 17 elements listed in the figure are the criteria associated with each conception.

organizations where needs, tasks, val-

Figure 1: Models of organizational performance and their associated criteria.

ues, and perceptions must compete

6 February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

was not associated specifically with any stability. One of the most important one hand, the PMO has an active role to

of the models. roles for the PMO is to monitor and play relative to the internal focus

A precision must be made to differ- control the performance of projects. through the development and dissemi-

entiate between open systems and Another important role is the standard- nation of project management metho-

rational goal models. The open systems ization of methods and processes. At dology, the fostering of internal com-

model values effectiveness. On the the same time, the PMO is part of mul- munication including the presentation

other hand, the rational goal model val- tiple project management networks of project results to upper manage-

ues efficiency, profitability, and ROI. where projects and ad hoc committees ment, and the development of compe-

The competing values approach are created, dissolved, and re-created tencies. A PMO is often responsible for

has been applied in a variety of areas. according to project management creating the common language relative

Originally, it emerged in the public sec- needs. Projects are temporary organiza- to project management. At the same

tor (Rohrbaugh, 1981), but several tions often associated with innovation time, the PMO is connected to the exter-

sectors have been studied since: higher and change, disruptive or incremental, nal world by means of consultant firms

education (Pounder, 2002), manufactur- as each project brings a new and and project management associations.

ing (McDermott & Stock, 1999), research unique solution to a particular prob- When a PMO is asked to benchmark the

and development (Jordan, Streit, & lem. In this context, the PMO supports internal project management process-

Binkley, 2003), and banking (Dwyer, creativity and innovation, or at the very es, the internal common language must

Richard, & Chadwick, 2003), as well as a least should not impede it. The PMO be translated to a universal common

cross-sector study (Stinglhamber, participates in the line of control, giving language. The PMO is an entity in which

Bentein, & Vandenberghe, 2004). More- the necessary stability while at the there exists a permanent arbitrage

over, Cameron and Quinn (1999) same time encouraging innovation and between internal and external focuses.

account for more than a thousand inter- change with flexibility. In this sense, a The examination of the two dimen-

ventions in organizations from several PMO can be said to be an ambidextrous sions in the specific context of the PMO

industrial sectors as diversified as agri- entity in developing ability in both con- confirms the existence of paradoxes

culture, insurance, and construction. trol and flexibility (Tushman & O’Reilly, identified by the competing values

This wide empirical base confirms the 1996). These examples illustrate the framework within a project manage-

applicability of this approach in various paradox between control and flexibility ment context. The evaluation of the

organizational contexts. as it applies in the context of PMOs. organizational performance of the

This approach has two important PMO can shed light on the different

strengths: the values underlying the eval- The Focus Dimension: Paradox Between perspectives from which organizational

uation become obvious and the changes Internal and External performance can be examined based

in the way these values are exerted are The PMO adopts an outright external on the values of those evaluating. The

also identified (Morin, Savoie, & focus when, to measure project and competing values framework repre-

Beaudin, 1994; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, project management results, it looks at sents a means to make these values

1983). In conclusion, the competing val- quantitative financial indicators and explicit, which will then lead to an

ues approach has the potential to grasp compares itself to other organizations understanding of what constitutes a

the dynamic of organizations by creat- or industries. Kendall and Rollins (2003) contribution to the performance of the

ing a dialogue between people having suggest that the main indicators for PMO and of the entire organization.

different, sometimes opposite, values measuring the value added of a PMO

that underlie their evaluation of organi- are related to three major elements: Methodology

zational performance. • reduction of the life cycle of projects; The methodological framework for this

• completion of more projects during research is based upon a constructivist

The Competing Values Framework in

the fiscal year with the same epistemology. In this epistemology,

the Context of PMOs

resources; and the phenomenon is in the reality and the

Because the empirical portion of this

• tangible contribution for reaching researcher in part of the interaction

research is centered on the PMO, the

organizational goals in terms of cost that takes place between the researcher

two dimensions and the paradoxes that

reduction, revenue increase, and a and the object of study. Knowledge cre-

these dimensions give rise to are exam-

better return on investment. ation is the ultimate objective (Allard-

ined in the context of the PMO.

Poesi & Maréchal, 1999). It modifies the

The Structure Dimension: Paradox The professionalization of project more traditional researcher role by “lis-

Between Flexibility and Control management also contributes to the tening” to the reality (Midler, 1994). In

The PMO usually belongs to the hierarchy fact that organizations want to compare the case of PMOs, this position is

and, as such, participates in maintaining and share their best practices. On the appropriate, as theories are almost

February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 7

A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management

PAPERS

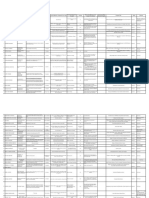

Industrial Sector Telecommunication Financial Multimedia Financial

Years since implementation of first PMO 13 9 5 2

Number of PMOs (n ⫽ 11) 4 3 3 1

Number of interviewees (n ⫽ 49) 13 16 15 5

Interviewees by role

Project manager 3 3 1 1

PMO director 0 5 2 1

Manager in PMO 4 2 0 0

Executives 2 1 1 1

HR 1 0 2 0

Financial 1 1 1 0

Other manager 2 1 1 1

PMO staff 0 3 7 1

Table 1: Profile of respondents.

nonexistent and the complexity found is proposed that can capture these per- into the four conceptions (Quinn &

in the reality cannot be explained using spectives and tensions. Rohrbaugh, 1983) adapted for use with

existing simple models and a positivist This research is part of a mixed- PMOs (see Figure 1). Respondents were

approach (Hobbs & Aubry, 2007). Just method program of research built for chosen to represent different roles,

as organizations are complex social robustness (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997). potentially leading to different concep-

entities, so too are the specific organi- In this specific research project, a case- tions of the PMO’s contribution to orga-

zational project management struc- study approach has been used to nizational performance (see Table 1).

tures that encompass PMOs. The explore and better understand the con- In addition to interviews, a ques-

methodological strategy is designed to tribution of PMOs to organizational tionnaire was built with the objective

understand such complexity. performance (Yin, 1989). Four organi- of capturing the different conceptions of

Drawing on Van de Ven’s (2007) zations participated in this research. A the PMO’s contribution and their under-

engaged scholarship brings together retrospective historical approach cov- lying values. The questionnaire contains

different points of view of key people ering the period since before the imple- the same 17 criteria. Respondents were

involved with PMOs, using a combina- mentation of the first PMO was adopt- asked to assess the importance of each

tion of qualitative and quantitative ed. The periods covered ranged from 2 of the criteria in their current context

instruments. PMOs represent a com- to 13 years, with an average of 7.24 using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 was

plex phenomenon not only by the vari- years. As is common among PMOs not important at all and 5 was very

ety of their expressions, but also by the globally, the PMOs in these organiza- important. Criteria with a score of 4 or 5

number of entities they relate to in a tions were restructured every few years were considered important.

single organization. In matrix organiza- (Hobbs & Aubry, 2007). A total of 11 dif-

tions, projects naturally form networks, ferent PMOs were analyzed, each con-

Empirical Results

which converge in one or more PMOs. stituting a case study. A Typology of PMOs Based on

Yet, within a single organization there Two types of data were collected: Organizational Performance Criteria

are multiple managers and profession- interviews and a questionnaire. The As mentioned previously, the compet-

als in relationships with the PMO. How most important data came from inter- ing values framework takes into

do they value the PMO’s contribution to views where open-ended questions were account the values within organiza-

organizational performance? It asked specifically on the performance of tions, and it provides an instrument

depends on the perspective of each of the PMO. Interviews were codified and that helps highlight paradoxes between

these stakeholders. In the quest for a analyzed in a grounded theory approach values. The diagram shown in Figure 1

better understanding of the PMO’s con- (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Transcripts forms a typology based upon the four

tribution to organizational perfor- were coded using the 17 criteria from the different conceptions of organizational

mance, a global methodological strategy competing values framework grouped performance. Each PMO from the case

8 February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

Equilibrium can be observed that project managers

Internal Focus Internal/External External Focus do recognize the importance of the

PMO’s contribution in the human rela-

Flexibility 1 1 3

tions and rational goals criteria. In this

Equilibrium 1 0 2 particular case, the PMO is active in

flexibility/control human resource functions participat-

Control 2 1 0 ing in the career path of people working

in projects. However, project managers

Table 2: Number of PMOs classified by the importance of their organizational performance criteria.

do not recognize that internal process-

es are as important. This may be

because project managers perceive

studies has been assigned a position single organization. This should trans- these processes to be a constraint on

within this framework so that they can late in this research into different pat- their freedom to act. The PMO director

be compared more easily with each terns for different stakeholders in their considers all criteria as important. This

other (see Table 2). evaluation of the importance of organi- situation is not specific to this case—

Each of these case studies has its zational performance criteria. Figure 2 the same result was observed in almost

own dynamics. Space restrictions pre- illustrates this phenomenon within one all cases. This confirms the positive bias

vent these from being explored here. In organization from the case studies. It of PMO managers when asked to assess

all, the results are coherent with the pertains to the evaluation of the existing the PMO’s contribution to organiza-

proposals from the competing values PMO at the time of interviews. As can be tional performance. Other managers

framework. There is no such thing as a observed, differences exist between within the PMO are more critical

perfect balance, but rather different val- actors in their assessment of the impor- specifically of human resource criteria.

ues underlie what organizational per- tance of the performance criteria. Otherwise, these managers recognize

formance represents in organizations Globally, results confirm the posi- the importance to other groups of crite-

(Cameron, 1986). A plurality of perspec- tive contribution of PMOs to organiza- ria. Executives recognize some impor-

tives on the contribution to organiza- tional performance. The Likert scale tance for all groups of criteria, but none

tional performance is observed. The offers the choices of low values of reach the level of significant impor-

results show that certain perspectives importance, but no criteria falls under tance. This is consistent with the poor

prevail at certain times and evolve with the middle position, which indicates perception of project management’s

the context. One problem when try- that all criteria are of at least some ability to contribute to organizational

ing to understand the contribution of importance. The results of one case performance reported by Thomas et al.

PMOs to organizational performance is with 15 respondents are illustrative but (2002). Curiously, the human resource

related to the fleetingness of the PMO cannot be generalized. manager does not attribute that much

itself (Hobbs & Aubry, 2007). Assessing An examination of the variations in importance to the PMO’s contribution

something that is fast-moving contains responses between stakeholders in dif- to human resource performance. This

in itself a major limitation. In this ferent roles is informative. In Figure 2, it may be a reflection of issues related to

research, the evolution of the PMO and

the evolution of the perception of its

contribution to organizational per-

5

formance were tracked. Results from

Importance of criteria

the pre-PMO period have been intro- 4

duced in this analysis. However, no

(means)

pattern resembling a predetermined 3

life cycle in the evolution of their con- 2

tribution to organizational perfor-

mance was found. 1

Human relations Internal processes Rational goals Open systems

The Actor’s View of the PMO’s Groups of criteria

Contribution to Organizational Project Manager PMO Director Manager within PMO

Performance Executive HR Manager Financial Manager

As discussed earlier, the competing val-

Manager Elsewhere PMO Employee

ues framework is based upon the

assumption that many conceptions of

Figure 2: Importance of organizational performance criteria by role.

organizational performance coexist in a

February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 9

A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management

PAPERS

jurisdiction over human resource each of the four models and the 17 cri- according to employee wishes. It is

issues. The human resource managers teria. The sets of indicators create value unusual that an organization structured

do recognize the PMO within the inter- in two ways. First, they enrich the by project (which is the case here)

nal processes and rational goals crite- understanding of the PMO’s contribu- stresses the contribution that personnel

ria. PMO employees are of particular tion to organizational performance make to projects and intensifies the

interest; they attribute significant by providing detail that is meaningful role of the PMO in human resources

importance to human resource and in this context. Second, they provide management. But management of

open system criteria but not that much the basis for instruments to measure the human resources, in this organizational

to internal process and rational goal presence of the models in real organiza- context, is a particularly critical func-

criteria. tional settings. tion. The personnel are exceedingly

These results also show some of the The goal here is to be more specific young: the average age is less than 30

paradoxes in the expectations relative and to identify relevant concrete indica- years old. This fact accounts for the

to the PMO’s contribution to perfor- tors in the context of PMOs. Transcripts strength of the company at the same

mance. For example, the financial man- of the interviews have first been coded time as it produces its own nightmares.

ager considers the internal processes using the 17 criteria. Then, excerpts These “teenagers” require a consider-

criteria to be the PMO’s most important have been scrutinized for their meaning able amount of supervision in order to

contribution to organizational per- in order to group multiple variations respect the project constraints and the

formance. However, project managers under a common indicator. From this never-ending challenges. There is an

consider these to be the least impor- second step, a list of 79 unique indica- important shortage in qualified person-

tant. When it comes time for the PMO tors was produced. nel in this high-technology sector. This

manager to discuss the contribution of Indicators inform us about the vari- company has invested extensively in

his/her unit with the financial manager, ety of possible ways the models mani- training in conjunction with local gov-

arguments concerning internal fest themselves and the different ways ernments. It has also implemented an

processes will probably be important, that measurements can be made in the internal school to provide skilled work-

but the same arguments are not as like- different PMOs. An advantage of this ers for its own development needs.

ly to convince the project managers. It exercise is to render explicit and opera- Furthermore, personnel turnover is sig-

is easy to see how these differences in tional notions about the contribution of nificant. In summary, the management

perceptions and appreciations can lead the PMO to organizational perfor- of human resources is an important

to tensions and even to conflicts. mance that until now may have function in which the PMO plays an

Results from the competing values remained abstract. See Appendix A for active role.

framework may also offer the opportu- the complete list of indicators. The significant number of indica-

nity to open up discussion between dif- tors identified within the human rela-

ferent and sometimes opposite ways of Indicators Within the Human tion conception shows that underlying

understanding the PMO’s contribution Resources Conception values exist in organizations to assess the

to organizational performance. The indicators related to human re- contribution of the PMO to organiza-

sources foster a clearer understanding tional performance regarding the human

The Development of Indicators of the role that the PMO can play in this resources. A PMO manager confirms the

Specific to the Evaluation of the area. Indicators vary greatly from one impact of his entity on the degree of sat-

PMO’s Contribution to Organi- organization to the next. It appears that isfaction of project managers:

zational Performance each of the four organizations has a dif-

Well, we took it all [multiple PMOs]

The four conceptions and the 17 gener- ferent flavor in the way the human

and centralized it; it [the degree of

ic criteria initially proposed within the resource contribution of the PMO is

satisfaction of the employee] went

competing values framework (Quinn & valued. For example, the organization from 0 to 24 in 12 months. The ener-

Rohrbaugh, 1983) can be applied in dif- in the multimedia industry stands out gy, the empowerment—there was a

ferent contexts. For this reason they are with the largest number of indicators in huge improvement.

at a more abstract level. Cameron and human resources. The scope of these

Quinn (1999) recognize that the four indicators often covers all of the It is also notable that the PMO plays

models and the 17 criteria are quite resources working on projects rather a social role and that it has an influence

abstract and recommend that sets of than only PMO employees or project on the work-family balance. Analysis

criteria be developed that are specific managers. In this case, the PMO plays a also revealed that the capacity for nego-

to a particular use. In a manner consis- direct role in the development of com- tiation is a competence essential to the

tent with this recommendation, specific petencies for personnel, according to resolution of conflicts surrounding

sets of indicators were developed for the needs of upcoming projects, and the state of advancement of projects.

10 February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

line, and there was a need in anoth-

The role of PMOs within human One of the financial services case

er product line, we could move that

resource management is often neglected organizations had two interrelated

person over if the competence and

in the literature on PMOs with the excep- PMOs: a central one and one in a busi-

the profile both matched the

tion of a few authors that dedicated their ness unit. These two PMOs don’t value requirements.

efforts to emphasizing this role the same elements as far as the quality

(Crawford & Cabanis-Brewin, 2006; of deliverables and communications Productivity in project management

Huemann, Keegan, & Turner, 2007). management is concerned. This is is a constant challenge. The challenge is

From the qualitative analysis, it can be understandable in complementary even more evident in international

seen that the PMO can make a signifi- but paradoxical terms: the business- organizations where there is competi-

cant contribution to organizational unit PMO values product quality and tion between different units in different

performance regarding human business results, while the central PMO locations. Productivity in project man-

resources and that concrete indicators values process maturity and project agement becomes an important factor

can be used to assess this. performance in terms of cost, schedule, for decisions as to where projects will be

and the project requirements. As can be executed. The role of PMOs in project

Indicators Within the Internal

seen from this example, two PMOs in productivity is often recognized in the

Processes Conception

the same organization may have com- literature (Kendall & Rollins, 2003).

The internal processes conception of

plementary but conflicting priorities. These authors link the PMO’s productiv-

organizational performance shows the

ity directly to its legitimacy.

largest number of individual indicators Indicators Within the Rational Goals

The criterion of planning in the

of the four conceptions. This empha- Conception

PMO context mostly refers to their

sizes the position of project manage- The indicators for the rational goals or

strategic and multiproject functions.

ment and the PMO in their traditional efficiency conception are less numer-

Indicators proposed by respondents

roles of process management. ous but are the most frequently cited.

give some idea of the concrete out-

Many indicators bear on the criteria Indicators included the profit criterion,

comes that relate to the strategic action

of information and communication which is not surprising; they reflect the

of PMOs in selecting the right projects.

management. The PMO seems to col- interest in selecting the right projects—

Indicators also emphasize the role of

laborate in many networks and play a the ones that contribute to the busi-

the PMO in the portfolio equilibrium

central role in the circulation of infor- ness’s bottom line. The contribution

regarding their risks and their short-

mation. A respondent emphasizes this of the PMO to organizational per-

and long-term benefits. Capacity plan-

role when saying: formance is recognized through its

ning indicators recognize the PMO’s

involvement in portfolio and program

I think that the PMO has an impor-

role in the allocation of resources on

management. Regarding the productiv-

tant role in the sense that they have the long run, the capacity to deliver,

ity criterion, the contribution of PMOs

a vision of what is going on else- and the capacity for internal resources

can be significant, particularly in the

where in the organization. . . . to absorb changes from projects. The

allocation and efficient use of

Normally, the PMO has antennae in alignment of employees’ objectives

resources. This point highlights an

each portfolio. . . . I think it could with organizational objectives was also

have a unifying role.

important issue for organizations hav-

found under the planning criteria. This

ing multiple highly specialized expert

indicator recognized that PMOs are

profiles working on multiple projects.

Indicators also reflect both the qual- involved in the appraisal process of

From the case studies, this issue was of

ity of information and the ease of its flow individuals working on projects.

prime importance in two organizations

throughout the organization. The crite- There are two indicators related to

having projects where 200 to 300

ria dedicated to the stability of processes efficiency criterion. The first one refers

employees work in parallel. In those

pinpoints more specifically the tradi- to the relationship that a PMO has with

two organizations, PMOs centralize the

tional role of PMOs in standardization of other parts of the organization. From

allocation of human resources. The idea

project management. The criteria of interviewees, this refers to numerous

here is to not leave anyone “on the

control included of course meeting inefficient meetings with PMO employ-

bench.” The director of a PMO pin-

costs, deadlines, and project scope. ees or managers. PMOs often perform a

pointed his role in the allocation of

However, PMO control is becoming monitoring and controlling function on

project managers:

increasingly diversified and is often project performance. In order to

exercised on the processes themselves. We wanted to use project manage- accomplish this mission, additional

Of particular interest is the situation ment resources in a better way so information to that available on reports

with multiple PMOs where the values that, for example, if a project man- or Web sites is needed. Different com-

given to indicators are quite different. ager was freed up in one product mittees or meetings are called to share

February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 11

A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management

PAPERS

information. People working on proj- justify the number of staff working in it. formance. Research on organizational

ects repeat the same information in The criterion of responsiveness includ- performance in project management

several different meetings, resulting in ed two indicators that were mentioned does not produce entirely satisfactory

inefficiency and frustration. At the quite often by respondents: (1) the results. Each piece of research brings

same time, the role of the PMO in nego- PMO should be able to respond quickly important contributions—but consid-

tiation when it comes time to decide on in order to make projects succeed and ered all together, a global vision of proj-

the status report color is recognized. (2) the PMO should be able to adapt to ect management performance at the

The second indicator mentioned is different situations. organizational level is still lacking.

project success and, more specifically, Indicators in this open system con- The competing values framework

the role of the PMO in fostering project ception contrast with the ones included has the advantage of integrating the

success. in the internal processes conception. financial perspective of performance

This confirms that paradoxes exist. There with the other conceptions in order to

Indicators Within the Open System are individuals that value the respect of form a multidimensional perspective.

Conception project management processes, while at Indeed, the four conceptions of the

Indicators within the open systems or the same time in the same organization, framework give us a multifaceted repre-

effectiveness conception are the fewest others value exactly the opposite and sentation of the performance of organi-

in number. These mostly deal with flex- encourage delinquency. The competing zational project management. The

ibility, adaptation, and innovation in values framework offers an opportunity rational goals and efficiency conception

project management. The first criteri- to acknowledge these paradoxes and, integrates the economic values of prof-

on, growth of the organization, refers from there, to open up a dialogue to itability, project management efficiency,

directly to the business side of the develop a common basis and under- and return on investment. The open sys-

organization, taking into account sales, standing of organizational performance. tems and effectiveness conception

qualitative results, and effectiveness. This work supports the recognition of the includes variables that measure growth

These elements relate to the benefits diversity of the contributions a PMO can and take into consideration innovation

from projects. It emphasizes that the make to an organization. And also it and project effectiveness. The human

PMO could be involved in a wider proj- should help to develop the awareness of relations conception emphasizes the

ect life cycle, covering the benefits from PMO managers and their employees of development of human resources, cohe-

projects. This stretches project man- the paradoxes that are at work in their sion, and personnel morale. All of these

agement toward the product life cycle organizations regarding their perform- elements are often absent from the eval-

(Jugdev & Müller, 2005). ance. This approach can be a valuable uation of organizational performance.

The criterion of flexibility, adapta- instrument to initiate a dialogue and The internal processes conception

tion, and innovation show numerous come to a common understanding of captures measurements related to cor-

indicators, few of which are shared what is valued. PMO actions could then porate processes tied to project manage-

from one case to another, except for be aligned on this common understand- ment such as project delivery method-

delinquency, with respect to project ing of organizational performance. ologies, communication processes, and

methodology. One respondent stated: knowledge management processes.

Indicators of Output Quality

“A lot of flexibility, what matters to me is Overall, the competing values model

The quality criteria include three indi-

the result; I couldn’t care less if we used bears directly on performance (objective

cators. First, the quality of the product

a saw or a screwdriver to get there.” This variable) instead of bearing on success

has been included here, as many inter-

highlights the fact that the contribution factors (explanatory variables).

viewees mentioned this element in

of the PMO to organizational perfor- Organizational performance must

relation with the PMO’s contribution to

mance is not limited to the establishment be examined from different viewpoints

the overall quality performance. The

of a methodology in project manage- and be scrutinized at several loci of

second and third are indicators of satis-

ment (from the internal processes con- analysis. PMOs are positioned at the

faction of the PMO sponsor and clients

ception), but also the flexibility with interface of several entities, some of

of the PMO. These indicators are quite

which the PMO encourages its use. which belong to project networks and

common when assessing quality.

While no indicators were mentioned in others to operational organizations

the evaluation by the external entities Conclusion (Lampel & Jha, 2004). They are in touch

criterion, respondents mentioned some The aim of this study is to understand with the projects, programs, project port-

for the criteria of having links with the the contribution of the PMO to organi- folios, corporate strategy, and functional

external environment. Benchmarking zational performance with a view to and business units. The PMO is there-

was mentioned often in a context of jus- understanding project management’s fore at the center of numerous perspec-

tification of the PMO, particularly to contribution to organizational per- tives on organizational performance. ■

12 February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

References with a strategic project office: Select, management system. Harvard Business

Allard-Poesi, F., & Maréchal, C. (1999). train, measure, and reward people for Review, 74(1), 75–85.

Construction de l’objet de recherche organization success. Boca Raton, FL: Kendall, G. I., & Rollins. S. C. (2003).

[Construction of the research object]. Auerbach. Advanced project portfolio manage-

In R.-A. Thiétart (Ed.), Méthodes de Dai, C. X. Y., & Wells, W. G. (2004). An ment and the PMO: Multiplying ROI at

recherche en management [Research exploration of project management warp speed. Boca Raton, FL: J. Ross

methods in management] (pp. 34–56). office features and their relationship to Publishing.

Paris: Dunod. project performance. International Lampel, J., & Jha, P. J. (2004). Models of

Boyne, G. A. (2003). What is public Journal of Project Management, 22, project orientation in multiproject

service improvement? Public 523–532. organizations. In P. W. G. Morris & J. K.

Administration, 81, 211–227. Dietrich, P., & Lehtonen, P. (2004). Pinto (Eds.), The Wiley guide to manag-

Brown, S. L., & Eisenhardt, K. M. Successful strategic management in ing projects (pp. 223–236). Hoboken,

(1997). The art of continuous change: multi-project environment: Reflections NJ: Wiley.

Linking complexity theory and time- from empirical study. Paper presented McDermott, C. M., & Stock, G. N.

paced evolution in relentlessly shifting at the IRNOP VI Conference, Turku, (1999). Organizational culture and

organizations. Administrative Science Finland. advanced manufacturing technology

Quarterly, 42, 1–34. Dwyer, S., Richard, O. C., & Chadwick, K. implementation. Journal of Operations

Cameron, K. S. (1981). Construct space (2003). Gender diversity in manage- Management, 17, 521–533.

and subjectivity problems in organiza- ment and firm performance: The influ-

Merriam-Webster’s collegiate diction-

tional effectiveness. Public Productivity ence of growth orientation and organi-

ary (11th ed.). (2007). Springfield, MA:

Review, 5(2), 105–121. zational culture. Journal of Business

Merriam-Webster.

Cameron, K. S. (1986). Effectiveness as Research, 56, 1009–1019.

Midler, C. (1994). L’auto qui n’existait

paradox: Consensus and conflict in Hobbs, B., & Aubry, M. (2007). A multi-

pas [The car that didn’t exist]. Paris:

conceptions of organizational effective- phase research program investigating

InterÉditions.

ness. Management Science, 32, 539–553. project management offices (PMOs):

The results of phase 1. Project Morin, E. M., Savoie, A., & Beaudin, G.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (1999).

Management Journal, 38(1), (1994). L’efficacité de l’organisation:

Diagnosing and changing organiza-

74–86. Théories, représentations et mesures

tional culture: Based on the competing

[Effectiveness of the organization:

values framework. Reading, MA: Huemann, M., Keegan, A., & Turner, R. J.

Theories, representation and measures].

Addison-Wesley. (2007). Human resource management

Montréal, Québec: Gaëtan Morin éditeur.

Cameron, K. S., & Whetten, D. A. in the project-oriented company: A

review. International Journal of Norrie, J., & Walker, D. H. T. (2004).

(1983). Organizational effectiveness: A

Project Management, 25, 315–329. A balanced scorecard approach to proj-

comparison of multiple models. New

ect management leadership. Project

York: Academic Press. Ibbs, C. W., Reginato, J., & Kwak, Y. H.

Management Journal, 35(4), 47–56.

Cooke-Davies, T. J. (2000). Towards (2004). Developing project manage-

improved project management prac- ment capability: Benchmarking, matu- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative

tice: Uncovering the evidence for effec- rity, modeling, gap analysis, and ROI research & evaluation methods.

tive practices through empirical studies. In P. W. G. Morris & J. K. Pinto Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

research. Unpublished doctoral thesis, (Eds.), The Wiley guide to managing Pounder, J. S. (2002). Public accounta-

Metropolitan University, Leeds, United projects (pp. 1214–1233). Hoboken, NJ: bility in Hong Kong higher education:

Kingdom. Wiley. Human resource management implica-

Cooke-Davies, T. J. (2002). The “real” Jordan, G. B., Streit, D., & Binkley, S. J. tions of assessing organizational effec-

success factors on projects. (2003). Assessing and improving the tiveness. International Journal of Public

International Journal of Project effectiveness of national research labora- Sector Management, 15, 458–474.

Management, 20(3), 185–190. tories. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983).

Cooke-Davies, T. J. (2004). Project Management, 50(2), 228–235. A spatial model of effectiveness crite-

management maturity models. In Jugdev, K., & Müller, R. (2005). A ret- ria: Towards a competing values

P. W. G. Morris & J. K. Pinto (Eds.), rospective look at our evolving under- approach to organizational analysis.

The Wiley guide to managing projects standing of project success. Project Management Science, 29, 363–377.

(pp. 1234–1264). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Management Journal, 36(4), 19–31. Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). Operationalizing

Crawford, K. J., & Cabanis-Brewin, J. Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). the competing values approach: Mea-

(2006). Optimizing human capital Using balanced scorecard as a strategic suring performance in the employment

February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 13

A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management

PAPERS

service. Public Productivity Review, Lessons for team leadership. organisations as information pro-

5(2), 141–159. International Journal of Project cessing systems? Paper presented

Savoie, A., & Morin, E. M. (2002). Les Management, 22, 533–544. at the PMI Research Conference,

représentations de l’efficacité organisa- Thomas, J. L., Delisle, C., Jugdev, K., & London.

tionnelle: Développements récents Buckle, P. (2002). Selling project man- Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research:

[Representations of the organizational agement to senior executives: Framing Design and methods. Newbury Park,

effectiveness: Recent developments]. In the moves that matter. Newtown Square, CA: Sage.

R. Jacob, A. Rondeau, & D. Luc (Eds.), PA: Project Management Institute.

Transformer l’organisation: La gestion Thomas, J. L., & Mullaly, M. E. (Eds.).

stratégique du changement [Transfor- (2008). Researching the value of

ming the organization: The strategic project management. Newtown Monique Aubry, PhD, is a professor in the grad-

management of change] (pp. 206–231). Square, PA: Project Management uate programs in project management at the

Montréal, Québec: Revue Gestion. Institute. School of Business and Management at the

Shenhar, A. J., Dvir, D., Levy, O., & Thompson, M. P., McGrath, M. R., & Université du Québec à Montréal. She is an

Maltz, A. C. (2001). Project success: Whorton, J. (1981). The competing active researcher within the Project

A multidimensional strategic concept. values approach: Its application and Management Research Chair under the aegis of

Long Range Planning, 34, 699–725. utility. Public Productivity Review, 5(2), project governance. Before her academic

Stewart, W. E. (2001). Balanced score- 188–200. career, she worked for more than 20 years in

card for projects. Project Management the management of major projects in the finan-

Turner, R. J., & Keegan, A. E. (2004).

Journal, 32(1), 38–53. cial sector. She is a member of the Project

Managing technology: Innovation,

Management Institute’s Standards Member

Stinglhamber, F., Bentein, K., & learning, and maturity. In P. W. G.

Advisory Group.

Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Congruence Morris & J. K. Pinto (Eds.), The Wiley

de valeurs et engagement envers l’or- guide to managing projects (pp.

ganisation et le groupe de travail 567–590). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

[Values congruence and engagement Tushman, M. L., & O’Reilly, C. A., III. Brian Hobbs, PhD, PMP, Project Management

towards the organization and working (1996). Ambidextrous organizations: Research Chair (www.pmchair.uqam.ca), has

group]. Psychologie du Travail Managing evolutionary and revolu- been a professor at the Université du Québec à

et des Organisations, 10(2), tionary change. California Manage- Montréal in the Master’s Program in Project

165–187. ment Review, 38(4), 8–30. Management for 25 years, a program accredited

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged by the Project Management Institute’s Global

qualitative research: Techniques and scholarship: Creating knowledge for Accreditation Center. He has been a member of

procedures for developing grounded the- science and practice. Oxford, UK: PMI’s Standards and Research Member Advisory

ory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Oxford University Press. Groups. He has presented many papers at both

Thamhain, H. J. (2004). Linkages of Winch, G. M. (2004, July). Rethinking research and professional conferences world-

project environment to performance: project management: Project wide.

14 February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

Appendix: List of Indicators contribution of PMOs to organizational Table A1 presents indicators within con-

This Appendix presents the list of all 79 performance. Indicators have been clas- ceptions of human resources, output

unique indicators that were identified sified using the conceptions on per- quality, and internal processes. Table A2

from the four case studies. Indicators formance from the competing values presents indicators within rational goals

provide an explicit element to assess the framework (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983). and open systems conceptions.

CRITERIA INDICATORS CRITERIA INDICATORS

Indicators Within Human Resources Conception Indicators Within Internal Processes Conception

1. Value of human 1. Empowerment 6. Information and 1. Accuracy of information in progress

resources working 2. Stimulating projects (participate to communication report

in project something big) management 2. Transparency of information in

3. Visibility for good work in projects progress report

4. Individual assessment 3. Circulation of the information on

5. Internal recruitment privileged projects (transverse role)

6. Team work valued 4. Keeping the memory of projects for

7. Trust in PMO forecasting (historical statistics)

5. Existence of project documentation

2. Training and 8. Training in project management 6. Capacity to absorb a lot of infor-

emphasis on 9. Level of experience of the personnel mation (project managers and

development working in PMO coordinators)

10. Encouragement for PMP 7. Creation of open places for people

11. Individual development plan for project to discuss

management competencies 8. Politics—visibility of the CEO

12. Diversity in competencies 9. Learning from errors

13. Coaching

14. Organization of events—knowledge 7. Stability in 10. Standardization in the way things

transfer processes are done

15. Change management in project 11. Importance of the resource

management appointment process

12. Existence and stability of project

3. Moral on project 16. Pleasure in working management processes

personal 17. Career job security

18. Employee satisfaction in project 8. Control 13. Rigor in the project management

19. Work-family equilibrium process

20. Number of overtime hours 14. Control of the appointment process

to avoid thieving

4. Conflict 21. Conflict prevention 15. Capacity to act (difference between

resolution and 22. Resolution of conflict in HR management monitoring and controlling)

search for 23. Negotiation on progress report 16. Control of project delivery date

cohesion (e.g., color code) 17. Control of costs

24. Negotiation on actions to be taken from 18. Control of scope

progress report 19. Control of earned value

25. Negotiation on project selection in portfolio 20. Ratio number of changes/respect

of cost

Indicators Within Output Quality

21. Equilibrium between time and

5. Output quality 1. Quality of the product budget

2. Satisfaction of the sponsor 22. Control of risks

3. Satisfaction of clients 23. Percent of precision in control data

Table A1: List of indicators within conceptions: Human resources, output quality, and internal processes.

February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 15

A Fresh Look at the Contribution of Project Management

PAPERS

CRITERIA INDICATORS CRITERIA INDICATORS

Indicators Within Rational Goals Indicators Within Open System

9. Profit 1. Profit from projects 13. Growth 1. Sales results

2. Benefits planning within 2. Qualitative element from busi-

project business case ness case (business positioning)

3. Effectiveness

10. Productivity 3. Order in productivity

4. Best utilization of resources in 14. Flexibility/ 4. Innovator, creator, and good at

project management (leave less adaptation/ conflict or problem resolution

people on the bench) innovation in 5. Hiring of project management

5. Index of productivity project personnel having creative skills

6. Bureaucracy management 6. Existence of initiatives in project

7. Internal competition (e.g., between management methodology

units in different countries) (sometimes being delinquent)

8. Existence of an organizational 7. PMO product a variety of reports

structure to deliver projects 8. Hiring of external consultants to

know the best practices in project

11. Planning in 9. Importance of the strategic dimension in management

goals to reach the selection of the “good” projects 9. Evolution in project management

10. Equilibrium in projects of a portfolio process and tools

(risk, benefits on the short-, medium-, 10. Participation of stakeholders in

and long-term value) the development and evolution of

11. Prediction of the delivery capabilities project management processes

(resource allocation)

12. Alignment of enterprise objectives with 15. Assessment by none

the employees’ objectives external entities

12. Efficiency 13. Efficiency in the relations between 16. Links with 11. Link with the local PMI (some-

PMO and functional or business units— external times too much!)

negotiation on projects environment 12. Benchmarking

14. Project success (PMO impacts on

projects) 17. Readiness 13. Being agile

14. Responsiveness in appointment

when urgent need

Table A2: List of indicators within conceptions: Rational goals and open system.

16 February 2011 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- PoolSpaN USPHDocument47 pagesPoolSpaN USPHpetar.petrov.111964No ratings yet

- New Talents: Talent FormatDocument4 pagesNew Talents: Talent Formatjoaollo4954100% (2)

- Reviews for finalDocument7 pagesReviews for finalantt234111eNo ratings yet

- Same Game Different Rules How To Get Ahead Without Being A Bully Broad Ice Queen or (Jean Hollands) (Z-Library)Document289 pagesSame Game Different Rules How To Get Ahead Without Being A Bully Broad Ice Queen or (Jean Hollands) (Z-Library)Kef7No ratings yet

- The Nature of B2B MarketingDocument14 pagesThe Nature of B2B MarketingAnshu Singh100% (1)

- C 02 S & D (R & 3D S) : MEC 430 - Machine Design - IIDocument80 pagesC 02 S & D (R & 3D S) : MEC 430 - Machine Design - IIAhmd MahmoudNo ratings yet

- ETEEAP BS ME Project Management - 2022-2023-2Document8 pagesETEEAP BS ME Project Management - 2022-2023-2Roderick P. ManaigNo ratings yet

- Statement On Academic Freedom and Critical Pedagogy in The Face of Global, National and Local ConflictDocument6 pagesStatement On Academic Freedom and Critical Pedagogy in The Face of Global, National and Local ConflictAnti-Racism Working Group of the Sociology Departmental Council80% (5)

- Customer Relationship Management of McDonaldDocument10 pagesCustomer Relationship Management of McDonaldMayank SinghNo ratings yet

- WikiDocument113 pagesWikiEnisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: LAN Design: Scaling NetworksDocument25 pagesChapter 1: LAN Design: Scaling Networkskakembo hakimNo ratings yet

- Peace Quaters StudyDocument3 pagesPeace Quaters StudyPopoola SamuelNo ratings yet

- Section 2a - Final - 2 - 10 - 15Document10 pagesSection 2a - Final - 2 - 10 - 15Dana RamosNo ratings yet

- Ra 9344Document3 pagesRa 9344jdenilaNo ratings yet

- President Joe Biden's Stimulus PlanDocument19 pagesPresident Joe Biden's Stimulus PlanThe College FixNo ratings yet

- Culinary Test Exam 1Document18 pagesCulinary Test Exam 1Sapna SharmaNo ratings yet

- DLL Quarter 4 WK 8 Geneva MendozaDocument37 pagesDLL Quarter 4 WK 8 Geneva MendozaGeneva MendozaNo ratings yet

- Hybrid Electric VDocument23 pagesHybrid Electric VDeepesh HingoraniNo ratings yet

- Project Example A1-1130H-1400W Air Handling Unit With PHE - (2.2m3/s) 2.20 m3/sDocument12 pagesProject Example A1-1130H-1400W Air Handling Unit With PHE - (2.2m3/s) 2.20 m3/samirin_king100% (1)

- Concert Performance AgreementDocument4 pagesConcert Performance AgreementND_entertainment_UNo ratings yet

- Key Words PDFDocument11 pagesKey Words PDFJane KnightNo ratings yet

- Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument7 pagesCoronary Artery Diseasejmar767No ratings yet

- He Imes Eader: Obama Promises Rigorous ReviewDocument36 pagesHe Imes Eader: Obama Promises Rigorous ReviewThe Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- MC Script Opening Speech EnglishDocument2 pagesMC Script Opening Speech EnglishShazwanShah100% (3)

- Chapter 2Document99 pagesChapter 2Anish KumarNo ratings yet

- Grey-Sample New SampleDocument2 pagesGrey-Sample New SampleHimadripeeu PeeuNo ratings yet

- Martial Arts Jutekwon Ecuador PDFDocument34 pagesMartial Arts Jutekwon Ecuador PDFJHON FERNANDO ESPIN CUEVANo ratings yet

- Account StatementDocument3 pagesAccount StatementSekhar RayuduNo ratings yet