Professional Documents

Culture Documents

G.R. No. 227070 - Adamson University Faculty and Employees Union v. Adamson University

Uploaded by

Jay jogsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

G.R. No. 227070 - Adamson University Faculty and Employees Union v. Adamson University

Uploaded by

Jay jogsCopyright:

Available Formats

The principles

§ Grounds for termination under the Labor Code

§ Serious Misconduct as a just cause for the dismissal of an employee

§ Use of expletives as a casual expression of surprise or exasperation is not serious misconduct

per se

§ Principle of totality of infractions

§ Acts of unfair labor practice

§ Unfair labor practices violative of the constitutional right of workers to self-organize

§ Employer's management prerogative to dismiss an employee is valid as long as it is done in

good faith and without malice

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 227070, March 9, 2020

ADAMSON UNIVERSITY FACULTY AND EMPLOYEES UNION,

v. ADAMSON UNIVERSITY

LEONEN, J.:

Delos Reyes was a university professor and the assistant chairperson of the Social Sciences

Department of Adamson University. He was also the president of the Adamson University Faculty

and Employees Union.

Adamson received an administrative complaint against Delos Reyes alleging that Delos

Reyes violated the University Code of Conduct and Republic Act No. 7610 for abusing

Josephine’s daughter, Paula Mae. By Josephine's account, Paula Mae encountered Delos Reyes

as the professor was about to enter the faculty room of the Department of Foreign Languages.

Paula Mae was holding the doorknob on her way out of the office, while Delos Reyes held the

doorknob on the other side. When Paula Mae stepped aside, Delos Reyes allegedly exclaimed

the words "anak ng puta" and walked on without any remorse. This caused emotional trauma to

Paula Mae.

Delos Reyes was issued a Notice of Dismissal. He sought reconsideration, but this was

denied. Adamson put out a paid advertisement on the Philippine Daily Inquirer's newspaper and

website, which Delos Reyes claimed tarnished his reputation by announcing his dismissal.

Delos Reyes filed a Notice of Strike before the National Conciliation and Mediation Board, but

the parties eventually agreed to refer the matter to voluntary arbitration.

The Panel of Voluntary Arbitrators ruled that Delos Reyes was validly dismissed.

Delos Reyes filed a Petition for Review, but this was denied. The Court of Appeals

preliminarily found that Delos Reyes was "amply accorded his right to procedural due process." It

went onto find him guilty of gross misconduct after considering Paula Mae's minority and her

family's circumstances. It also found his defenses of alibi and denial unsubstantiated and weak

against Paula Mae's positive and categorical testimony.

Hence, this petition.

§ Grounds for termination under the Labor Code

Q. What are the grounds for termination under the Labor Code?

The following are grounds for termination under the Labor Code:

ARTICLE 297. (282] Termination by Employer. — An employer may terminate an

employment for any of the following causes:

(a) Serious misconduct or willful disobedience by the employee of the lawful orders of his

employer or representative in connection with his work;

(b) Gross and habitual neglect by the employee of his duties;

(c) Fraud or willful breach by the employee of the trust reposed in him by his employer or duly

authorized representative;

(d) Commission of a crime or offense by the employee against the person of his employer or

any immediate member of his family or his duly authorized representatives; and

(e) Other causes analogous to the foregoing.

§ Serious Misconduct as a just cause for the dismissal of an employee

Q. What constitutes serious misconduct that which will warrant the dismissal of an

employee under paragraph (a) of Article 282 of the Labor Code?

In National Labor Relations Commission v. Salgarino, this Court elaborated on what

constitutes serious misconduct:

Misconduct is defined as improper or wrong conduct. It is the transgression of some

established and definite rule of action, a forbidden act, a dereliction of duty, willful in character

and implies wrongful intent and not mere error of judgment. The misconduct to be serious within

the meaning of the act must be of such a grave and aggravated character and not merely trivial

or unimportant. Such misconduct, however serious, must nevertheless be in connection with the

work of the employee to constitute just cause from his separation.

In order to constitute serious misconduct which will warrant the dismissal of an employee

under paragraph (a) of Article 282 of the Labor Code, it is not sufficient that the act or conduct

complained of has violated some established rules or policies. It is equally important and

required that the act or conduct must have been performed with wrongful intent.

Misconduct is not considered serious or grave when it is not performed with wrongful

intent. If the misconduct is only simple, not grave, the employee cannot be validly dismissed.

§ Use of expletives as a casual expression of surprise or exasperation is not serious

misconduct per se

Q. Is the use of expletives as a casual expression of surprise or exasperation a

serious misconduct per se?

The use of expletives as a casual expression of surprise or exasperation is not serious

misconduct per se that warrants an employee's dismissal. However, the employee's subsequent

acts showing willful and wrongful intent may be considered in determining whether there is a just

cause for their employment termination.

A teacher exclaiming "anak ng puta" after having encountered a student is an

unquestionable act of misconduct. However, whether it is serious misconduct that warrants the

teacher's dismissal will depend on the context of the phrase's use. "Anak ng puta" is similar to

"putang ina" in that it is an expletive sometimes used as a casual expression of displeasure, rather

than a personal attack or insult. In Pader v. People:

In Reyes vs. People, we ruled that the expression "putang ina mo" is a common enough

utterance in the dialect that is often employed, not really to slander but rather to express anger or

displeasure. In fact, more often, it is just an expletive that punctuates one's expression of profanity.

We do not find it seriously insulting that after a previous incident involving his father, a drunk Rogelio

Pader on seeing Atty. Escolango would utter words expressing anger. Obviously, the intention was

to show his feelings of resentment and not necessarily to insult the latter. Being a candidate running

for vice mayor, occasional gestures and words of disapproval or dislike of his person are not

uncommon.

A review of the records reveals that the utterance in question, "anak ng puta," was an

expression of annoyance or exasperation. Both petitioner and Paula Mae were pulling from each

side of the door, prompting the professor to exclaim frustration without any clear intent to maliciously

damage or cause emotional harm upon the student. That they had not personally known each other

before the incident, and that petitioner had no personal vendetta against Paula Mae as to mean

those words to insult her, confirm this conclusion.

However, it is petitioner's succeeding acts that aggravated the misconduct he committed. He

not only denied committing the act, but he also refused to apologize for it and even filed a counter-

complaint against Paula Mae for supposedly tarnishing his reputation. He even refused to sign the

receiving copy of the notices that sought to hold him accountable for his act.

While uttering an expletive out loud in the spur of the moment is not grave misconduct per

se, the refusal to acknowledge this mistake and the attempt to cause further damage and distress to

a minor student cannot be mere errors of judgment. Petitioner's subsequent acts are willful, which

negate professionalism in his behavior. They contradict a professor's responsibility of giving primacy

to the students' interests and respecting the institution in which he teaches. In the interest of self-

preservation, petitioner refused to answer for his own mistake; instead, he played the victim and

sought to find fault in a student who had no ill motive against him.

Indeed, had he been modest enough to own up to his first blunder, petitioner's case would

have gone an entirely different way.

The open defiance and disrespect to school authorities and processes are magnified in this

case as respondent refused to sign any order served on him. He even used, intentionally or

unintentionally the letterhead of the AUFEA in his letters to the Committee and signed the same as

AUFEA President when he is being complained of as a faculty member and not in his capacity as

the Union President. This only shows that respondent had the propensity to commit and display

among his peers and, more so, to the students a misbehavior which is a characteristic (sic) of

misconduct.

§ Principle of totality of infractions

Q. What is the principle of totality of infractions?

In Sy v. Neat, Inc, this Court discussed the principle of totality of infractions:

In determining the sanction imposable on an employee, the employer may consider the

former's past misconduct and previous infractions. Also known as the principle of totality of

infractions, the Court explained such concept in Merin v. National Labor Relations Commission,

et al., thus:

The totality of infractions or the number of violations committed during the period of

employment shall be considered in determining the penalty to be imposed upon an erring

employee. The offenses committed by petitioner should not be taken singly and separately.

Fitness for continued employment cannot be compartmentalized into tight little cubicles of

aspects of character, conduct and ability separate and independent of each other. While it may

be true that petitioner was penalized for his previous infractions, this does not and should not

mean that his employment record would be wiped clean of his infractions. After all, the record of

an employee is a relevant consideration in determining the penalty that should be meted out

since an employee's past misconduct and present behavior must be taken together in

determining the proper imposable penalty. Despite the sanctions imposed upon petitioner, he

continued to commit misconduct and exhibit undesirable behavior on board. Indeed, the

employer cannot be compelled to retain a misbehaving employee, or one who is guilty of acts

inimical to its interests. It has the right to dismiss such an employee if only as a measure of self-

protection.

§ Acts of unfair labor practice

Q. What are the various acts of unfair labor practice?

The various acts of unfair labor practice are found under Article 259 of the Labor Code:

ARTICLE 259. [248] Unfair Labor Practices of Employers. — It shall be unlawful for an

employer to commit any of the following unfair labor practices:

(a) To interfere with, restrain or coerce employees in the exercise of their right to self-

organization;

(b) To require as a condition of employment that a person or an employee shall not join a

labor organization or shall withdraw from one to which he belongs;

(c) To contract out services or functions being performed by union members when such

will interfere with, restrain or coerce employees in the exercise of their right to self-organization;

(d) To initiate, dominate, assist or otherwise interfere with the formation or administration

of any labor organization, including the giving of financial or other support to it or its organizers

or supporters;

(e) To discriminate in regard to wages, hours of work and other terms and conditions of

employment in order to encourage or discourage membership in any labor organization. Nothing

in this Code or in any other law shall stop the parties from requiring membership in a recognized

collective bargaining agent as a condition for employment, except those employees who are

already members of another union at the time of the signing of the collective bargaining

agreement. Employees of an appropriate bargaining unit who are not members of the

recognized collective bargaining agent may be assessed a reasonable fee equivalent to the

dues and other fees paid by members of the recognized collective bargaining agent, if such

non-union members accept the benefits under the collective bargaining agreement: Provided,

That the individual authorization required under Article 242, paragraph (o) of this Code shall not

apply to the non-members of the recognized collective bargaining agent;

(f) To dismiss, discharge or otherwise prejudice or discriminate against an employee for

having given or being about to give testimony under this Code; (g) To violate the duty to bargain

collectively as prescribed by this Code;

(h) To pay negotiation or attorney's fees to the union or its officers or agents as part of the

settlement of any issue in collective bargaining or any other dispute; or

(i) To violate a collective bargaining agreement.

The provisions of the preceding paragraph notwithstanding, only the officers and agents

of corporations, associations or partnerships who have actually participated in, authorized or

ratified unfair labor practices shall be held criminally liable.

§ Unfair labor practices violative of the constitutional right of workers to self-organize

Q. What constitutional right is violated by unfair labor practices?

Unfair labor practices are violative of the constitutional right of workers to self-organize:

ARTICLE 258. [247] Concept of Unfair Labor Practice and Procedure for Prosecution

Thereof. — Unfair labor practices violate the constitutional right of workers and employees to

self-organization, are inimical to the legitimate interests of both labor and management,

including their right to bargain collectively and otherwise deal with each other in an atmosphere

of freedom and mutual respect, disrupt industrial peace and hinder the promotion of healthy and

stable labor-management relations.

Consequently, unfair labor practices are not only violations of the civil rights of both labor

and management but are also criminal offenses against the State which shall be subject to

prosecution and punishment as herein provided.

Subject to the exercise by the President or by the Secretary of Labor and Employment of

the powers vested in them by Articles 263 and 264 of this Code, the civil aspects of all cases

involving unfair labor practices, which may include claims for actual, moral, exemplary and other

forms of damages, attorney's fees and other affirmative relief, shall be under the jurisdiction of

the Labor Arbiters. The Labor Arbiters shall give utmost priority to the hearing and resolution of

all cases involving unfair labor practices. They shall resolve such cases within thirty (30)

calendar days from the time they are submitted for decision.

Recovery of civil liability in the administrative proceedings shall bar recovery under the

Civil Code.

No criminal prosecution under this Title may be instituted without a final judgment finding

that an unfair labor practice was committed, having been first obtained in the preceding

paragraph. During the pendency of such administrative proceeding, the running of the period of

prescription of the criminal offense herein penalized shall be considered interrupted: Provided,

however, That the final judgment in the administrative proceedings shall not be binding in the

criminal case nor be considered as evidence of guilt but merely as proof of compliance of the

requirements therein set forth.

§ Employer's management prerogative to dismiss an employee is valid as long as it is done

in good faith and without malice

Q. Under what conditions is the employer's management prerogative to dismiss an

employee valid?

An employer's management prerogative to dismiss an employee is valid as long as it is done

in good faith and without malice. In Wise and Co., Inc. v. Wise Co., Inc. Employees Union-NATU:

The Court holds that it is the prerogative of management to regulate, according to its

discretion and judgment, all aspects of employment. This flows from the established rule that labor

law does not authorize the substitution of the judgment of the employer in the conduct of its

business. Such management prerogative may be availed of without fear of any liability so long as it

is exercised in good faith for the advancement of the employers' interest and not for the purpose of

defeating or circumventing the rights of employees under special laws or valid agreement and are

not exercised in a malicious, harsh, oppressive, vindictive or wanton manner or out of malice or

spite.

You might also like

- 004 - KINDS of EMPLOYEES - Philippine Span Asia Carriers V Pelayo - DigestDocument2 pages004 - KINDS of EMPLOYEES - Philippine Span Asia Carriers V Pelayo - DigestKate GaroNo ratings yet

- ADAMSON UNIVERSITY FACULTY AND EMPLOYEES UNION, Represented by Its President, and ORESTES DELOS REYES vs. ADAMSON UNIVERSITY (G.R. No. 227070. March 9, 2020)Document10 pagesADAMSON UNIVERSITY FACULTY AND EMPLOYEES UNION, Represented by Its President, and ORESTES DELOS REYES vs. ADAMSON UNIVERSITY (G.R. No. 227070. March 9, 2020)Marianne Hope VillasNo ratings yet

- Conte - Cooling-Off Period DIGESTDocument4 pagesConte - Cooling-Off Period DIGESTAngela ConteNo ratings yet

- Univ of Immaculate Conception V Sec of LaborDocument2 pagesUniv of Immaculate Conception V Sec of LaborMarc VirtucioNo ratings yet

- Bravo V Urios College DIGESTDocument2 pagesBravo V Urios College DIGESTJenniferPizarrasCadiz-Carulla100% (1)

- SC upholds dismissal of union members for illegal strikesDocument1 pageSC upholds dismissal of union members for illegal strikesRealPhy JURADONo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 227175 - Neren Villanueva vs. Ganco Resort and Recreation, Inc., Et AlDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 227175 - Neren Villanueva vs. Ganco Resort and Recreation, Inc., Et AlJay jogsNo ratings yet

- 9 Slord Development Corp. vs. Noya G.R. No. 232687Document2 pages9 Slord Development Corp. vs. Noya G.R. No. 232687Monica FerilNo ratings yet

- JESUS G. REYES Vs GLAUCOMA RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC., EYE REFERRAL CENTER and MANUEL B. AGULTO - Chapter 5 - Social JusticeDocument2 pagesJESUS G. REYES Vs GLAUCOMA RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC., EYE REFERRAL CENTER and MANUEL B. AGULTO - Chapter 5 - Social Justicerian5852No ratings yet

- 4 - Pacific Mills V AlonzoDocument1 page4 - Pacific Mills V AlonzoCheyz ErNo ratings yet

- AIM Vs AIM Faculty AssociationDocument2 pagesAIM Vs AIM Faculty AssociationAgnes Lintao100% (1)

- G.R. No. 241865 - TUMAODOS V. SAN MIGUELDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 241865 - TUMAODOS V. SAN MIGUELJay jogs100% (1)

- GR 170830 - Phimco Vs Pila (Labor)Document3 pagesGR 170830 - Phimco Vs Pila (Labor)Colleen Rose Guantero100% (2)

- Hugo Et Al., vs. Light Rail Transit AuthorityDocument2 pagesHugo Et Al., vs. Light Rail Transit AuthorityNej AdunayNo ratings yet

- Atok Big Wedge Company Vs GisonDocument1 pageAtok Big Wedge Company Vs Gisonsescuzar100% (1)

- Inocentes Et Al Vs RSCIDocument2 pagesInocentes Et Al Vs RSCIRex Regio100% (1)

- Divine Word University of Tacloban v. Secretary of Labor and Employment Et AlDocument2 pagesDivine Word University of Tacloban v. Secretary of Labor and Employment Et AlWinter Woods100% (1)

- SRL vs. Yarza (207828)Document3 pagesSRL vs. Yarza (207828)Thea FactorNo ratings yet

- PHIMCO V PILA (2010) : Strike PicketingDocument3 pagesPHIMCO V PILA (2010) : Strike PicketingClarisse-joan Bumanglag Garma100% (1)

- Moreno Vs San Sebastian CollegeDocument3 pagesMoreno Vs San Sebastian CollegePaulineNo ratings yet

- Manila Mandarin v. NLRCDocument1 pageManila Mandarin v. NLRCAnonymous Xkzaifvd100% (1)

- Navotas Shipyard Corp. vs. Montallana Et Al.Document2 pagesNavotas Shipyard Corp. vs. Montallana Et Al.PhilAeon100% (1)

- Samahang Manggagawa Sa Sulpicio Lines vs. Sulpicio Lines, Inc. - Case DigestDocument2 pagesSamahang Manggagawa Sa Sulpicio Lines vs. Sulpicio Lines, Inc. - Case DigestRoxanne PeñaNo ratings yet

- PROTECTIVE MAXIMUM SECURITY AGENCY v. FUENTES - Brito, Karen Daryl L.Document3 pagesPROTECTIVE MAXIMUM SECURITY AGENCY v. FUENTES - Brito, Karen Daryl L.Karen Ryl Lozada BritoNo ratings yet

- University of Immaculate Concepcion,. Inc. v. Sec. of LaborDocument4 pagesUniversity of Immaculate Concepcion,. Inc. v. Sec. of LaborEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- Manarpiis Vs Texan PhilippinesDocument3 pagesManarpiis Vs Texan PhilippinesNeil Mayor100% (1)

- (Labor 2 - Atty. Nolasco) : G.R. No. 196539 Perez, J. Digest By: IntiaDocument2 pages(Labor 2 - Atty. Nolasco) : G.R. No. 196539 Perez, J. Digest By: IntiaRaymund CallejaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 230005 - Seventh Fleet Security Services, Inc. vs. Rodolfo B. LoqueDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 230005 - Seventh Fleet Security Services, Inc. vs. Rodolfo B. LoqueJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Principles of constructive dismissal and intimidationDocument2 pagesPrinciples of constructive dismissal and intimidationJay jogsNo ratings yet

- SMC V Gomez Case Digest Krystal Grace PaduraDocument2 pagesSMC V Gomez Case Digest Krystal Grace PaduraKrystal Grace D. PaduraNo ratings yet

- Manila Mandarin vs. NLRCDocument1 pageManila Mandarin vs. NLRCJotham FunclaraNo ratings yet

- Paragele V GMADocument3 pagesParagele V GMAAllen Windel Bernabe67% (3)

- Petition for cancellation of union registration deniedDocument2 pagesPetition for cancellation of union registration deniedRikki Banggat100% (1)

- Andteq Industrial Steel Products vs. Edna Margallo, G.R. No. 181393, 28 July 2009.Document2 pagesAndteq Industrial Steel Products vs. Edna Margallo, G.R. No. 181393, 28 July 2009.Jeffrey MedinaNo ratings yet

- Abbott Lab Phils. Inc. Vs Abbott Lab Employees Union Gr131374Document2 pagesAbbott Lab Phils. Inc. Vs Abbott Lab Employees Union Gr131374Dani Eseque100% (4)

- Atok Big Wedge Company vs. Gison (JCL Digest)Document2 pagesAtok Big Wedge Company vs. Gison (JCL Digest)Jor LonzagaNo ratings yet

- Tanduay Distillery Labor Union Vs NLRCDocument4 pagesTanduay Distillery Labor Union Vs NLRCpatricia.aniya0% (1)

- ICT Marketing Services, Inc. Vs Sales, GR No.202090, 05 Sept 2015Document2 pagesICT Marketing Services, Inc. Vs Sales, GR No.202090, 05 Sept 2015chrisNo ratings yet

- SC Rules Against Team Pacific in Illegal Dismissal Case of Employee on Maternity LeaveDocument4 pagesSC Rules Against Team Pacific in Illegal Dismissal Case of Employee on Maternity LeaveSunny Tea50% (2)

- One Cannot Simply Substitute Certiorari Under Rule 65 For A Lost Remedy of Appeal As They Are Mutually Exclusive and Not Alternative or SuccessiveDocument2 pagesOne Cannot Simply Substitute Certiorari Under Rule 65 For A Lost Remedy of Appeal As They Are Mutually Exclusive and Not Alternative or SuccessiveShine Dawn InfanteNo ratings yet

- GR 214230 Security Banks Savings Corporation vs. Charles SingsonDocument2 pagesGR 214230 Security Banks Savings Corporation vs. Charles SingsonMylene Gana Maguen ManoganNo ratings yet

- Apelanio vs. ArcanysDocument2 pagesApelanio vs. ArcanysEmir Mendoza100% (3)

- Claudia's Kitchen, Inc. v. TanguinDocument2 pagesClaudia's Kitchen, Inc. v. TanguinBrenPeñarandaNo ratings yet

- Leus vs. St. Scholastica College Pregnancy DismissalDocument4 pagesLeus vs. St. Scholastica College Pregnancy DismissalNeil Mayor100% (1)

- Cruz VS PAFLU labor dispute saleDocument2 pagesCruz VS PAFLU labor dispute saleVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Legality of Employee Termination Based on Union Security ClauseDocument3 pagesLegality of Employee Termination Based on Union Security ClausedayneblazeNo ratings yet

- Lepanto Consolidated Mining v. DumapisDocument2 pagesLepanto Consolidated Mining v. DumapisJade Viguilla75% (4)

- Javier V Fly Ace Corp PDF FreeDocument2 pagesJavier V Fly Ace Corp PDF FreeKeyan Motol100% (1)

- FILSYSTEMS, Inc. V Puente GR No. 152832 Advincula, C.Document1 pageFILSYSTEMS, Inc. V Puente GR No. 152832 Advincula, C.Christopher AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- Sukhothai Cuisine Restaurant vs. CADocument2 pagesSukhothai Cuisine Restaurant vs. CAAnny Yanong100% (1)

- National Federation of Sugar Workers Vs OvejeraDocument2 pagesNational Federation of Sugar Workers Vs OvejeraRotsen Kho Yute100% (2)

- G.R. No. 200815Document2 pagesG.R. No. 200815Morin OcoNo ratings yet

- FINAL CASE DIGEST - HernandezDocument71 pagesFINAL CASE DIGEST - HernandezIa HernandezNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Bacus v. OpleDocument1 pageCase Digest - Bacus v. OpledaphvillegasNo ratings yet

- Lagrosas v. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Digest)Document2 pagesLagrosas v. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Digest)ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Adamson University Faculty and Employees Union. v. Adamson UniversityDocument2 pagesAdamson University Faculty and Employees Union. v. Adamson UniversityMark Anthony ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ceniza - Assignment Labor 2 - Post EmploymentDocument14 pagesCeniza - Assignment Labor 2 - Post Employmentezra cenizaNo ratings yet

- Just Causes and Due ProcessDocument9 pagesJust Causes and Due ProcessMartsu Ressan M. LadiaNo ratings yet

- Post Employment AssDocument14 pagesPost Employment Assezra cenizaNo ratings yet

- Serious Misconduct LectureDocument49 pagesSerious Misconduct LectureKristiana Montenegro Geling100% (1)

- Richardson Steel Corporation v. Union Bank of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesRichardson Steel Corporation v. Union Bank of The PhilippinesJay jogsNo ratings yet

- KLM Royal Dutch Airlines vs. TiongcoDocument2 pagesKLM Royal Dutch Airlines vs. TiongcoJay jogs100% (3)

- Allied Banking Corporation v. MacamDocument2 pagesAllied Banking Corporation v. MacamJay jogs100% (2)

- City of Tanauan v. MillonteDocument2 pagesCity of Tanauan v. MillonteJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Banta v. Equitable Bank, IncDocument2 pagesBanta v. Equitable Bank, IncJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Jacinto v. LitonjuaDocument1 pageJacinto v. LitonjuaJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Sps. Ty vs. Heirs of Spouses Leonardo Z. Palermo and Petronia DoloritosDocument3 pagesSps. Ty vs. Heirs of Spouses Leonardo Z. Palermo and Petronia DoloritosJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Locsin v. AustriaDocument2 pagesLocsin v. AustriaJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company (Comm Rev)Document1 pageMetropolitan Bank and Trust Company (Comm Rev)Jay jogsNo ratings yet

- de Joya v. MadlangbayanDocument2 pagesde Joya v. MadlangbayanJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Arakor Construction and Development Corporation v. Sta. MariaDocument2 pagesArakor Construction and Development Corporation v. Sta. MariaJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Home Guaranty Corporation v. ManlapazDocument1 pageHome Guaranty Corporation v. ManlapazJay jogs0% (1)

- Sampilo v. AmistadDocument2 pagesSampilo v. AmistadJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Lopez v. Saludo, JRDocument2 pagesLopez v. Saludo, JRJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Tuazon v. FuentesDocument2 pagesTuazon v. FuentesJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Asian Construction Dispute Denied ReviewDocument2 pagesAsian Construction Dispute Denied ReviewJay jogs100% (2)

- PNTC Colleges, Inc. vs. Time Realty, IncDocument2 pagesPNTC Colleges, Inc. vs. Time Realty, IncJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Camp John Hay Development Corporation v. Office of The OmbudsmanDocument2 pagesCamp John Hay Development Corporation v. Office of The OmbudsmanJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Mary Lane R. Kim v. QuichoDocument2 pagesHeirs of Mary Lane R. Kim v. QuichoJay jogs100% (1)

- Cayao v. Confederation of Sugar Producers CooperativesDocument2 pagesCayao v. Confederation of Sugar Producers CooperativesJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Seming vs. AlamagDocument2 pagesSeming vs. AlamagJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank vs. Aic Construction CorporationDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Bank vs. Aic Construction CorporationJay jogs100% (1)

- Bermon Marketing Communication Corporation vs. Sps. YacoDocument2 pagesBermon Marketing Communication Corporation vs. Sps. YacoJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Dumaran v. LlamedoDocument3 pagesDumaran v. LlamedoJay jogs100% (2)

- Spouses Rol vs Racho: Sale of definite portion of co-owned land null without consentDocument2 pagesSpouses Rol vs Racho: Sale of definite portion of co-owned land null without consentJay jogs100% (1)

- Trans Industrial Utilities, Inc. v. Metropolitan. Bank & Trust CompanyDocument2 pagesTrans Industrial Utilities, Inc. v. Metropolitan. Bank & Trust CompanyJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Sanggacala v. NPCDocument2 pagesSanggacala v. NPCJay jogs100% (3)

- WATERFRONT PHILIPPINES, INC. v. SSSDocument2 pagesWATERFRONT PHILIPPINES, INC. v. SSSJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Chanelay Development Corporation v. GsisDocument3 pagesChanelay Development Corporation v. GsisJay jogsNo ratings yet

- Principles of compensation for injury or death under Philippine maritime lawDocument5 pagesPrinciples of compensation for injury or death under Philippine maritime lawJay jogsNo ratings yet

- FOP/Dale Surbaugh ComplaintDocument13 pagesFOP/Dale Surbaugh ComplaintWSYX/WTTENo ratings yet

- Booking Report 10-1-2021Document3 pagesBooking Report 10-1-2021WCTV Digital TeamNo ratings yet

- Right To Strike and The Role of Judiciary in IndiaDocument5 pagesRight To Strike and The Role of Judiciary in IndiaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- G10 L1 Health TleDocument3 pagesG10 L1 Health TleparatosayoNo ratings yet

- Cdi8 Midterm Exam (Patiu Don Joshua)Document8 pagesCdi8 Midterm Exam (Patiu Don Joshua)Joshua PatiuNo ratings yet

- RESPOndentDocument17 pagesRESPOndentApurv ShenmareNo ratings yet

- Module 2 DRRR AnswersDocument1 pageModule 2 DRRR AnswersDalmendozaNo ratings yet

- Court upholds estafa convictionDocument22 pagesCourt upholds estafa convictionChristiane Marie BajadaNo ratings yet

- Tadeo - Matias vs. Republic, G.R. # 230751, Apr. 25, 2018Document9 pagesTadeo - Matias vs. Republic, G.R. # 230751, Apr. 25, 2018Kael MarmaladeNo ratings yet

- A Trustee's Fiduciar S Fiduciary Duties at The Star y Duties at The Start and End of Administr T and End of AdministrationDocument24 pagesA Trustee's Fiduciar S Fiduciary Duties at The Star y Duties at The Start and End of Administr T and End of AdministrationMulundu ZuluNo ratings yet

- GAO Agreement FormDocument2 pagesGAO Agreement FormOkwuogu ChisomNo ratings yet

- THE Abbottabad CM No.10-D2020 Ali: Peshawar Court, Bench. C.R. No.06-ADocument9 pagesTHE Abbottabad CM No.10-D2020 Ali: Peshawar Court, Bench. C.R. No.06-ASadaqat YarNo ratings yet

- Demand LetterDocument1 pageDemand LetterMark Bati100% (1)

- Procedures For Application For Small Estate DistributionDocument1 pageProcedures For Application For Small Estate DistributionAgitha GunasagranNo ratings yet

- XXX Vs PeopleDocument2 pagesXXX Vs PeopleAnnievin HawkNo ratings yet

- ExplanationsDocument4 pagesExplanationsroseann.duro20No ratings yet

- New Deshaun Watson Lawsuit (WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT)Document11 pagesNew Deshaun Watson Lawsuit (WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT)Houston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Counter - Affidavit: MODESTO C. MAHICON, of Legal Age, Filipino Citizen and ADocument5 pagesCounter - Affidavit: MODESTO C. MAHICON, of Legal Age, Filipino Citizen and APj TignimanNo ratings yet

- 5 Koike V Koike DONEDocument2 pages5 Koike V Koike DONEDanielle Kaye TurijaNo ratings yet

- Human Rights ResearchDocument8 pagesHuman Rights Researchjancel maeNo ratings yet

- gpujpthjp rk;kd; - Notice of Hearing in a Summary SuitDocument25 pagesgpujpthjp rk;kd; - Notice of Hearing in a Summary Suitsharanmit6630No ratings yet

- MBA21062 - Sumanth G - LAB Assignment-01Document6 pagesMBA21062 - Sumanth G - LAB Assignment-01Sumanth GNo ratings yet

- Zaldivia v. Reyes, 211 SCRA 277Document2 pagesZaldivia v. Reyes, 211 SCRA 277Andrea GarciaNo ratings yet

- Quizz 1.answerDocument3 pagesQuizz 1.answerKookie ShresthaNo ratings yet

- France Police Organizational StructureDocument15 pagesFrance Police Organizational StructureRemar Jhon HernanNo ratings yet

- FDR SAFETY TRAINING ONLINE OSH SEMINARDocument2 pagesFDR SAFETY TRAINING ONLINE OSH SEMINARJo SNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CriminologyDocument39 pagesIntroduction To CriminologyBernalyn Sisante ArandiaNo ratings yet

- Constitution - Lesson Plan 3, Oct 15, 2018 v2Document20 pagesConstitution - Lesson Plan 3, Oct 15, 2018 v2Jude AldonsNo ratings yet

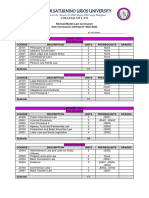

- FSUU College of Law RMLC ProspectusDocument3 pagesFSUU College of Law RMLC ProspectusDave Gato VestalNo ratings yet

- Penology, Punishment, Clemency and VictimologyDocument10 pagesPenology, Punishment, Clemency and VictimologyIH NONo ratings yet