Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Craniofacial Growth of Class III Subjects Six To Sixteen Years of Age

Craniofacial Growth of Class III Subjects Six To Sixteen Years of Age

Uploaded by

Keyla Paola De La Hoz FonsecaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Craniofacial Growth of Class III Subjects Six To Sixteen Years of Age

Craniofacial Growth of Class III Subjects Six To Sixteen Years of Age

Uploaded by

Keyla Paola De La Hoz FonsecaCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Article

Craniofacial growth of Class III subjects six to sixteen years of age

Sara M. Wolfea; Eustaquio Araujob; Rolf G. Behrentsc; Peter H. Buschangd

ABSTRACT

Objective: To characterize the mixed-longitudinal craniofacial growth of untreated, white, Class III

subjects 6 to 16 years of age.

Materials and Methods: Serial cephalograms of 19 females and 23 males with Class III

malocclusion were evaluated at three time points (6–8, 10–12, and 14–16 years of age). A similar

number of Class I controls were randomly selected and matched for age and sex. The

cephalograms were traced and digitized, and 20 variables were evaluated. Growth patterns were

quantified, and class and sex differences were evaluated using multi-level analyses.

Results: In comparison with Class I subjects, Class III subjects had significantly (P # .05) larger

mandibular plane angles, gonial angles, mandibular ramus heights, mandibular corpus lengths,

and SNB angles, with differences that were maintained between 6 and 16 years of age. Maxillary

lengths and ANB angles were significantly smaller and remained smaller in Class III subjects than

in Class I subjects. Lower face height, maxillary-mandibular differential, and mandibular body

length were also significantly larger and increased significantly more between 6 and 16 years of

age in Class III subjects. The WITS appraisal was significantly smaller in Class III subjects and

decreased significantly more over time. Most linear measures showed significant sex differences

favoring males; the angular measures and anteroposterior (AP) maxillomandibular relationships

showed no sex differences.

Conclusions: The AP maxillomandibular relationship of Class III subjects worsens over time. AP

discrepancies are primarily due to excessive mandibular growth, which produces a protrusive,

hyperdivergent phenotype. The AP discrepancies of males are larger than those of females, with

differences increasing over time. (Angle Orthod. 2011;81:211–216.)

KEY WORDS: Class III; Cephalometrics; Whites; Growth

INTRODUCTION more in extreme cases.’’ Regardless of the definition

used, the orthodontist’s understanding of how untreat-

Since 1737, when Bourdet first described the

ed Class III whites grow has been limited by the low

skeletal pattern of children with protruding chins, Class

prevalence of Class III malocclusions and the tenden-

III malocclusions have been characterized in various

cy to treat subjects at a younger age. The prevalence

ways. Angle1 defined Class III malocclusion as ‘‘the

of Class III malocclusion has been reported2,3 to range

relation of the jaws with all the lower teeth occluding

between 1.6% and 12.2%. National health surveys4,5

mesial to normal the width of one premolar or even

have shown that 4.9% of white children between 6 and

11 years of age and 6% of youths between 12 and

Private Practice, Birmingham, AL.

a

17 years of age display a bilateral mesiocclusion.

Professor, Orthodontic Department, St Louis University, St

b

Using negative overjet to classify Class III subjects,

Louis, Mo.

c

Professor and Department Chair, Orthodontic Department,

more recent surveys6,7 indicate a 1–4% prevalence of

St Louis University, St Louis, Mo. Class III malocclusion among North Americans.

d

Professor, Department of Orthodontics, Baylor College of Previous cross-sectional cephalometric character-

Dentistry, Dallas, Tex. izations have shown that when compared to Class I

Corresponding author: Dr Peter Buschang, Department of whites, Class III subjects have substantially smaller

Orthodontics, Baylor College of Dentistry, 3302 Gaston Ave,

Dallas, TX 75246 ANB angles,8–11 slightly smaller SNA angles,8,10,12,13

(e-mail: PHBuschang@bcd.tamhsc.edu) and substantially larger SNB angles.8,10,11,13 The saddle

Accepted: June 2010. Submitted: April 2010.

and cranial base flexure angles have also been shown

G 2011 by The EH Angle Education and Research Foundation, to be more acute among Class III subjects;9,14–16 a lack

Inc. of differences in cranial base angles has also been

DOI: 10.2319/051010-252.1 211 Angle Orthodontist, Vol 81, No 2, 2011

212 WOLFE, ARAUJO, BEHRENTS, BUSCHANG

reported.8,11,13 Similarly, MacDonald and coworkers16 were identified and digitized. The magnification (ap-

found no significant differences between Class III and proximately 6%) was not corrected.

Class I malocclusions for either the SNA angle or the Cephalometric measures were derived from the

maxillary depth. Larger mandibular dimensions have analyses of Jarabak and Fizzel,19 Jacobson,20 McNa-

commonly been cited8,10,13 as the predominant charac- mara,21 and Steiner22; they represent a variety of AP

teristic in the Class III subject. and vertical measurements reported to be significant in

While serial data are required to determine actual Class III development.

growth differences associated with untreated Class III

malocclusions, relatively few longitudinal studies have Statistical Analysis

been conducted. Baccetti et al.,17 who evaluated 22

Data were analyzed using multi-level statistical

white Class III subjects at two time points, showed that

models.23 Multi-level statistical analysis does not make

maxillomandibular relationships worsen over time.

the assumption of complete longitudinal data, nor does

However, because of the lack of untreated controls,

it require exact intervals between age groups, making

they were not able to determine growth deficiencies or

it well suited for this mixed-longitudinal study. Growth

excesses of the craniofacial components. Alexander et

curves were described as polynomials and estimated

al.,18 who described the longitudinal growth between 4

using iterative generalized least squares. The regres-

and 20 years of age of 103 Class III whites, also

sions consisted of intercept (size) and age (growth

showed definite worsening of anteroposterior (AP)

velocity at 11 years of age) terms. To center the

skeletal relationships, but they were also unable to

intercept, 11 was subtracted from the subjects’ ages

characterize the differences, again as a result of the

(ie, ages 7, 11, and 15 were changes to 24, 0, and 4,

lack of controls.

respectively). Separate analyses were performed to

In order to better understand the development of

evaluate class and sex differences.

skeletal differences among Class III subjects, this study

Each multi-level model estimated the constant and

was designed to evaluate the growth of Class III and

age terms, as well as group differences in the constant

matched Class I subjects between 6 and 16 years of age.

and age terms. The models’ constant terms described

the size or the angle of either Class I malocclusions or

MATERIALS AND METHODS

females, depending on the analysis, at 11 years of

Serial cephalometric radiographs were selected from age. The age terms described the yearly growth

the Bolton-Brush Growth Study Center in Cleveland, changes. The multi-level models also estimated group

Ohio; these radiographs represented white children differences (Class III minus Class I; male minus

aged 6–8, 10–12, and 14–16 years of age. Forty-two female) for both the constant and age terms.

Class III subjects were selected based on their molar Reliability analysis was performed using the Dahl-

relationships, as determined by the Bolton-Brush berg method’s error statistic [! (Sdeviations2/2n)].

Growth Study. Forty age-group and sex-matched Class The method errors of the linear measures ranged

I controls were randomly selected from the same between 0.74 mm and 2.1 mm, with mid-face length

sample. The subjects were classified as Class III or (Co-A) showing the greatest error. Angular measure-

Class I during the early permanent dentition, based on ment method errors ranged between 0.8u and 2.9u,

clinical observations and dental models. Subjects with with the cranial base angle (Ba-S-N) showing the

cleft lip, cleft palate, and other craniofacial syndromes greatest error.

were excluded. The sample was mixed longitudinal; all

of the subjects had records at two of the three age RESULTS

groupings; 34% of the sample had complete longitudinal

The multi-level models showed significant growth

series comprising three records.

changes for all of the variables except the cranial base

angle (Ba-S-N), articular angle (S-Ar-Go), and WITS

Cephalometric Tracing and Analysis

(Table 1). Eleven of the 20 measures (55%) showed

Lateral head films were traced on 0.003-inch frosted statistically significant differences between Class I and

acetate. Each film was traced by one investigator and Class III malocclusions. Lower face height (ANS-Me),

checked for accuracy by one of two investigators. Ten corpus length (Go-Pg), and the maxillomandibular

percent of the films were randomly chosen and differential (Mx-Md) were significantly larger in 11

retraced to assess reliability. All films were then year-old Class III subjects and demonstrated signifi-

digitized with a Numonics Accugrid Digitizer (Numo- cantly greater growth increases over time than Class I

nics Corp, Montgomeryville, Penn) and analyzed with subjects (Figure 1). The WITS appraisal was signifi-

the Dentofacial Planner software program, version cantly smaller at 11 years and it decreased signifi-

7.0.2 (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Sixteen landmarks cantly more between 6–16 years in Class Ill’s than in

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 81, No 2, 2011

GROWTH OF CLASS III SUBJECTS 213

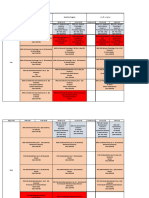

Table 1. Multi-level Growth Estimates for Untreated Class I Subjects and Class Differences (Class III 2 Class I) Between 6 and 16 Years of Age

Class I Subjects Class III 2 Class I Differences

Intercept Age Effects Intercept Age Effects

At 11 y of Standard Change Standard Standard Differences in Standard

Age Error Over Time Error Differences Error Change Over Time Error

N-Me* 112.58 0.58 2.27 0.07 — — — —

ANS-Me* 63.06 0.72 1.08 0.08 1.64 1.01 0.22 0.10

N-ANS* 50.08 0.28 1.01 0.04 — — — —

N-ANS/ANS-Me* 78.66 0.73 0.18 0.08 — — — —

MPA* 30.84 0.84 20.31 0.05 2.44 1.14 — —

S-N* 68.37 0.33 0.80 0.03 — — — —

Ba-S-N 130.10 0.56 20.08 0.07 — — — —

N-S-Ar* 123.12 0.55 0.17 0.08 — — — —

S-Ar-Go 139.20 0.60 20.07 0.10 — — — —

Ar-Go-Me* 131.97 0.75 20.38 0.05 2.23 1.02 — —

Co-A* 84.09 0.43 1.34 0.06 — — — —

ANS-PNS* 51.17 0.39 0.73 0.05 21.55 0.53 — —

Ar-Go* 44.81 0.45 1.18 0.06 1.37 0.59 — —

Go-Pg* 66.56 0.69 1.56 0.08 2.07 0.97 0.34 0.10

Co-Gn* 108.25 0.75 2.60 0.07 3.91 1.04 — —

ANB* 3.24 0.36 20.25 0.03 22.29 0.49 — —

SNA* 80.28 0.46 0.10 0.04 — — — —

SNB* 76.92 0.58 0.37 0.04 2.46 0.82 — —

Mx-Md* 23.50 0.60 1.11 0.09 5.29 0.85 0.25 0.12

WITS* 20.81 0.35 0.02 0.08 23.93 0.49 20.27 0.11

* Significant (P , .05) growth changes; — 5 Not statistically significant; Mx-Md 5 Co-Gn minus Co-A; Wits 5 A ) functional occlusal plane

minus B ) functional occlusal plane.

Class l’s. The mandibular plane angle (MPA), gonial length (ANS-PNS) and ANB angle were significantly

angle (Ar-Go-Me), ramus height (Ar-Go), mandibular smaller in Class III malocclusions, Figure 2.

length (Co-Gn), and the SNB angle were all significantly The multi-level models showed statistically significant

larger in the Class III group at 11 years of age; maxillary sex differences for eight measures (Table 2). The gonial

Figure 1. Measures demonstrating significant size differences at 11 years and significant growth differences between Class I subjects and

Class III subjects 6–16 years of age.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 81, No 2, 2011

214 WOLFE, ARAUJO, BEHRENTS, BUSCHANG

Figure 2. Measures demonstrating significant size differences at 11 years of age between Class I subjects and Class III subjects.

angle (Ar-Go-Me) was significantly greater in males than were all significantly larger in males and demonstrated

in females at age 11, with no significant growth significantly greater growth increases over time com-

differences. Total face height (N-Me), lower face height pared with females. Mandibular ramus height (Ar-Go)

(ANS-Me), upper face height (N-ANS), anterior cranial was significantly smaller in 11-year-old males but

base length (S-N), mid-face length (Co-A), mandibular showed significantly greater increases for males than for

body length (Go-Pg), and mandibular length (Co-Gn) females.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 81, No 2, 2011

GROWTH OF CLASS III SUBJECTS 215

Table 2. Multi-level Growth Estimates of Female Growth Changes and Sex Differences (male 2 females) Between 6 and 16 Years of Age

Female Male 2 Female Differences

Intercept Age Effects Intercept Age Effects

At 11 y of Standard Change Over Standard Standard Differences in Standard

Age Error Time Error Differences Error Change Over Time Error

N-Me* 111.11 0.81 1.95 0.06 2.98 1.13 0.64 0.12

ANS-Me* 62.56 0.70 1.02 0.07 2.66 0.99 0.35 0.10

N-ANS* 49.81 0.41 0.86 0.06 0.54 0.57 0.28 0.08

N-ANS/ANS-Me* 78.66 0.73 0.18 0.08 — — — —

MPA* 32.08 0.62 20.31 0.05 — — — —

S-N* 67.95 0.46 0.70 0.04 0.83 0.65 0.20 0.06

Ba-S-N 130.11 0.56 20.08 0.06 — — — —

N-S-Ar* 123.12 0.55 0.17 0.08 — — — —

S-Ar-Go 139.20 0.60 20.07 0.10 — — — —

Ar-Go-Me* 133.13 0.57 20.40 0.05 — — — —

Co-A* 83.13 0.60 1.20 0.09 1.91 0.84 0.30 0.12

ANS-PNS* 50.39 0.29 0.73 0.06 — — — —

Ar-Go* 45.59 0.49 1.03 0.08 20.12 0.69 0.29 0.12

Go-Pg* 66.56 0.69 1.56 0.08 2.07 0.97 0.34 0.10

Co-Gn* 109.13 0.82 2.34 0.09 2.27 1.15 0.53 0.13

ANB* 2.09 0.29 20.25 0.03 — — — —

SNA* 80.28 0.46 0.10 0.04 — — — —

SNB* 78.17 0.43 0.37 0.04 — — — —

Mx-Md* 26.17 0.52 1.24 0.06 — — — —

WITS* 22.79 0.33 20.13 0.06 — — — —

* Significant (P , .05) growth changes; — 5 Not statistically significant; Mx-Md 5 Co-Gn minus Co-A; Wits 5 A H functional occlusal plane

minus B H functional occlusal plane.

DISCUSSION In contrast to those of Class I subjects, the

mandibles of Class III subjects were more hyperdiver-

AP relationships of Class III subjects clearly worsen gent and substantially larger. The angular differences

between 6 and 16 years of age. Compared to Class I identified among Class III subjects in the present

subjects, Class III subjects had smaller ANB and larger study, including the increased mandibular plane and

SNB angles, as previously reported9,11,13 for samples larger gonial angles, have been previously well

evaluated cross sectionally. As expected, the Class III established.8,10,12 Supporting the present findings,

subjects in the present study also exhibited a greater ramus heights have been reported13 for Class

significantly larger maxillomandibular differential and III than for Class I subjects. Total mandibular length

a smaller WITS differential. Importantly, both of these has also been previously shown8,9 to be significantly

differentials worsened over time, indicating a worsen- larger in Class III subjects of similar ages. Increased

ing of the Class III malocclusion. Decreases in the corpus length among Class III subjects compared with

WITS measures and increases in the maxillomandib- Class I subjects has been previously identified by

ular differential have been previously reported17 for Jacobson and coworkers.10 The greater growth in-

Class III subjects followed longitudinally. The ANB creases in corpus length identified in the present study

angle in the present study probably did not worsen have not been previously shown. This indicates that it

over time as a result of the greater-than-expected is the remodeling pattern (ie, a development of a more

increases in lower facial height exhibited by Class III obtuse gonial angle and increases in corpus length

subjects. Similar increases in lower face height of associated with deposition of bone at the lower

Class III subjects have been reported18 between 4 and posterior aspect of the ramus), rather than condylar

20 years in age. It is possible that the ANB angle growth, that is the primary determinant of overall

maintained the same growth rates in Class I subjects mandibular excess among Class III subjects.

and Class III subjects because the anterior movements In contrast to their large, prognathic mandibles, the

of point B were masked by the inferior movements of maxillas of the Class III subjects in the present study

point B. The WITS better represents the true AP were orthognathic. MacDonald et al.16 also showed no

changes because it is measured from the occlusal significant differences between Class III subjects and

plane and is unaffected by the vertical changes that Class I subjects for either SNA or maxillary depth.

occur. While most other cross-sectional studies8,10,12,13 have

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 81, No 2, 2011

216 WOLFE, ARAUJO, BEHRENTS, BUSCHANG

reported maxillary retrusion among Class III subjects, 4. Kelly JE, Sanchez M, Van Kirk LE. An assessment of the

their results tend to be limited and inconsistent. For occlusion of teeth of children 6–11 years, United States.

Washington, DC: US DHEW Publication (HRA)74-1612; 1973.

example, Guyer et al.8 reported significant differences 5. Kelly JE, Harvey CJ. An assessment of the occlusion of the

in the SNA angle between Class I subjects and Class teeth in youths 12–17 years, United States. Washington,

III subjects for three of the four age groups evaluated; DC: US DHEW Publication (HRA)77-1644; 1977.

Battagel11 only found differences after all of the group 6. Proffit W, Fields H, Moray L. Prevalence of malocclusion

data had been combined; Tollaro et al.13 did not find and orthodontic treatment need in the United States:

estimates from the NHANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthod

significant differences among their 4- and 5-year-old

Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:97–106.

subsamples, but they did report differences for the 6- 7. Mills LF. Epidemiologic studies of occlusion. IV. The

year-olds and for the entire sample combined. Taken prevalence of malocclusion in a population of 1455 school

together, the present and previous studies indicate that children. J Dent Res. 1966;45:332–336.

even though the maxillas of Class III subjects are 8. Guyer EC, Ellis EE, McNamara JA, Behrents RG. Compo-

smaller, maxillary retrusion is relatively mild and nents of Class III malocclusion in juveniles and adolescents.

Angle Orthod. 1986;56:7–30.

represents only a minor contribution to the develop- 9. Reyes BC, Baccetti T, McNamara JA. An estimate of

ment of AP discrepancies. craniofacial growth in Class III malocclusion. Angle Orthod.

Sex differences, which increased over time, were 2006;76:577–584.

evident for most of the linear measures. Males were 10. Jacobson A, Evans WG, Preston CB, Sadowsky PL.

larger than females, and the differences increased with Mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod. 1974;66:140–171.

11. Battagel J. The aetiological factors in Class III malocclusion.

age. These results are consistent with an understand-

Eur J Orthod. 1993;15:347–370.

ing of craniofacial and somatic growth. Sex differences 12. Sanborn RT. Differences between the facial skeletal

in maxillary and mandibular growth favoring males patterns of Class III malocclusion and normal occlusion.

have been previously established.24,25 Sex differences Angle Orthod. 1955;25:208–222.

are small during childhood and become pronounced 13. Tollaro I, Baccetti T, Bassarelli V, Franchi L. Class III

during adolescence, as a result of the two extra years malocclusion in the deciduous dentition, a morphological

and correlation study. Eur J Orthod. 1994;16:401–408.

of childhood growth among males as well as the 14. Proff P, Will F, Bokan I, Fanghanel J, Gedrange T. Cranial

greater intensity of the male adolescent spurt. base features in skeletal Class III patients. Angle Orthod.

2008;78:433–439.

CONCLUSIONS 15. Jarvinen S. Saddle angle and maxillary prognathism: a

radiological analysis of the association between the NSAr

N Maxillomandibular relationships of Class III subjects and SNA angles. Br J Orthod. 1984;11:209–213.

progressively worsen between 6 and 16 years of 16. MacDonald KE, Kapust AJ, Turley PK. Cephalometric

age. changes after the correction of Class III malocclusion with

N Class III subjects have a somewhat smaller, but not maxillary expansion/facemask therapy. Am J Orthod Den-

tofacial Orthop. 1999;116:13–24.

more recessive, maxilla than do Class I subjects; 17. Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA Jr. Growth in the

maxillary size differences are established early and untreated Class III subject. Semin Orthod. 2007;13:130–

maintained through 16 years of age. 142.

N Class III subjects have larger, more protrusive 18. Alexander AE, McNamara JA Jr, Franchi L, Baccetti T.

mandibles than Class I subjects, with AP growth Semilongitudinal cephalometric study of craniofacial growth

in untreated Class III malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

excesses that accumulate over time. Class III Orthop. 2009;135:700.e1–14.

subjects also have hyperdivergent mandibles and 19. Jarabak J, Fizzel J. Technique and Treatment with Light

excessive growth of lower facial height. Wire Edgewise Appliances. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1972.

N Males are larger than females, with size differences 20. Jacobson A. The ‘‘Wits’’ appraisal of jaw disharmony.

increasing between 6 and 16 years of age. There Am J Orthod. 1975;67:125–138.

were no significant sex differences in AP maxillo- 21. McNamara JA. A method of cephalometric evaluation.

Am J Orthod. 1984;86:449–469.

mandibular and angular relationships. 22. Steiner C. Cephalometrics for you and me. Am J Orthod.

1953;39:729–755.

23. Hoeksma JB, van der Beek MCJ. Multilevel modelling of

REFERENCES longitudinal cephalometric data explained for orthodontists.

1. Angle EH. Classification of malocclusion. Dent Cosmos. Eur J Orthod. 1991;13:197–201.

1899;41:248. 24. Buschang PH, Tanguay R, Demirjian A, LaPalme L, Gold-

2. Huber RE, Reynolds JW. A dentofacial study of male stein H. Sexual dimorphism in mandibular growth of French-

students at the University of Michigan in the physical Canadian children 6 to 10 years of age. Am J Phys

hardening program. Am J Orthod. 1946;32:1–21. Anthropol. 1986;71:33–37.

3. Ast DB, Carlos JP, Cons NC. The prevalence and 25. Riolo ML, Moyers RE, McNamara JA Jr, Hunter WS. An

characteristics of malocclusion among senior high school Atlas of Craniofacial Growth. Monograph 2, Center for

students in upstate New York. Am J Orthod. 1965;51: Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan.

437–445. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan; 1974.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 81, No 2, 2011

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Written Examination Handbook For General Dentistry May 2021-MinDocument20 pagesWritten Examination Handbook For General Dentistry May 2021-MinMuhammad Hassan memonNo ratings yet

- Kode Icd 10 Gigi&MulutDocument4 pagesKode Icd 10 Gigi&MulutAgustinusSimanjuntak50% (2)

- Dental Laboratory Technology Specialist BlueprintDocument2 pagesDental Laboratory Technology Specialist BlueprintDr. Amr Khaled Al JabriNo ratings yet

- Nikaido 2018Document5 pagesNikaido 2018Carmen Iturriaga GuajardoNo ratings yet

- Crown and Root Landmarks, Division Into Thirds, Line Angles and Point AnglesDocument62 pagesCrown and Root Landmarks, Division Into Thirds, Line Angles and Point AnglesSara Al-Fuqaha'No ratings yet

- Introduction of OrthodonticDocument8 pagesIntroduction of OrthodonticDr.Shakeer AlukailiNo ratings yet

- Obtundents, Mummifying Agents and FluoridesDocument11 pagesObtundents, Mummifying Agents and Fluoridesrupesh dalaviNo ratings yet

- EN - It Takes A Village - Ana Maria CiobanuDocument13 pagesEN - It Takes A Village - Ana Maria CiobanuAna Maria CiobanuNo ratings yet

- Component Analysis of Class II, Division 1 Discloses Limitations For Transfer To Class I PhenotypeDocument19 pagesComponent Analysis of Class II, Division 1 Discloses Limitations For Transfer To Class I PhenotypeLuisa Fernanda Perdomo MarinNo ratings yet

- Basic Endodontic InstrumentsDocument15 pagesBasic Endodontic InstrumentsIna BogdanNo ratings yet

- Ceramic in Dentistry: - History & Evolution - Types of Ceramic - Usage of CeramicDocument32 pagesCeramic in Dentistry: - History & Evolution - Types of Ceramic - Usage of Ceramicneji_murniNo ratings yet

- Clinical Significance OF Dental Anatomy, Histology, Physiology, and OcclusionDocument77 pagesClinical Significance OF Dental Anatomy, Histology, Physiology, and OcclusionDiana ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Interappointment Flare-Up in Endodontics: A Case Report and An OverviewDocument4 pagesInterappointment Flare-Up in Endodontics: A Case Report and An OverviewAnonymous cTV8BbsCeNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Oral and Maxillofacial SurgeryDocument347 pagesAnesthesia For Oral and Maxillofacial SurgeryMaryol BallesterosNo ratings yet

- 40 Ejercicios Del Ingles TecnicoDocument16 pages40 Ejercicios Del Ingles TecnicoFermín ClementeNo ratings yet

- Articulo MsxillaryDocument13 pagesArticulo MsxillaryAndres CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Principles and Practice of Implant DentistryDocument448 pagesPrinciples and Practice of Implant Dentistryamirmaafi100% (5)

- Dental Tourism English PDFDocument2 pagesDental Tourism English PDFAditya VitaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Health Vi: (H6PH-lab-18)Document8 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Health Vi: (H6PH-lab-18)payno gelacioNo ratings yet

- J Ajodo 2018 07 018Document7 pagesJ Ajodo 2018 07 018Zaheer bashaNo ratings yet

- 07 Gracis-Occlusion1Document12 pages07 Gracis-Occlusion1ValentinaNo ratings yet

- Venture Scape MapDocument4 pagesVenture Scape Mapapi-722297718No ratings yet

- Marketing ProjectDocument20 pagesMarketing ProjectItisha JainNo ratings yet

- 6 Weeks Observership ProgrammeDocument20 pages6 Weeks Observership ProgrammeAbdelrahman GalalNo ratings yet

- Marjo Owens Job 3Document1 pageMarjo Owens Job 3api-508833937No ratings yet

- Early Childhood Caries (ECC) : Allison Restauri, RDH, BSDH EDU 653 1 1 - 0 3 - 2 0 1 2Document25 pagesEarly Childhood Caries (ECC) : Allison Restauri, RDH, BSDH EDU 653 1 1 - 0 3 - 2 0 1 2Justforkiddslaserdental ChNo ratings yet

- Tooth Development 1Document14 pagesTooth Development 1ahmedfawakh0No ratings yet

- DENTAL EXAMINATION - Transcript - TaggedDocument6 pagesDENTAL EXAMINATION - Transcript - Taggedpereiraortiz.tahinaNo ratings yet

- Level 1,2,3 Dentistry-Spring 2024 Timetable-RamadanDocument14 pagesLevel 1,2,3 Dentistry-Spring 2024 Timetable-RamadanSadek MohamedNo ratings yet

- The Marketing Plan For ColgateDocument15 pagesThe Marketing Plan For ColgateWyman Chow100% (1)