Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Nurse S Role in Improving Health Disparities Experienced by The Indigenous Maori of New Zealand

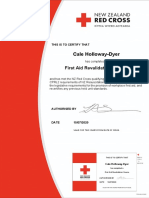

Uploaded by

Cale HollowayOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Nurse S Role in Improving Health Disparities Experienced by The Indigenous Maori of New Zealand

Uploaded by

Cale HollowayCopyright:

Available Formats

Contemporary Nurse

ISSN: 1037-6178 (Print) 1839-3535 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcnj20

The nurse’s role in improving health disparities

experienced by the indigenous Māori of New

Zealand

Katherine Evelyn Theunissen

To cite this article: Katherine Evelyn Theunissen (2011) The nurse’s role in improving health

disparities experienced by the indigenous Māori of New Zealand, Contemporary Nurse, 39:2,

281-286, DOI: 10.5172/conu.2011.39.2.281

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2011.39.2.281

Published online: 17 Dec 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1741

View related articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcnj20

Copyright © eContent Management Pty Ltd. Contemporary Nurse (2011) 39(2): 281–286.

The nurse’s role in improving health

disparities experienced by the

indigenous Mā- ori of New Zealand

KATHERINE EVELYN THEUNISSEN

Department of Nursing, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

ABSTRACT

Many countries across the globe experience disparities in health between their indigenous and

non-indigenous people. The indigenous Māori of New Zealand are the most marginalized and

deprived ethnic group with the poorest health status overall. Factors including the historical British

colonization, institutional discrimination, healthcare workforce bias and the personal attitudes and

beliefs of Māori significantly contribute to disparities, differential access and receipt of quality health

services. Māori experience more barriers towards accessing health services and as a result achieve

poorer health outcomes. Contradicting translations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi have created much debate

regarding social rights as interpreted by Oritetanga (equal British citizenship rights) and whether

or not Māori are entitled to equal opportunities or equal outcomes. Inconsistent consideration of

Māori culture in the New Zealand health system and social policy greatly contributes to the current

health disparities. Nurses and healthcare professionals alike have the gifted opportunity to truly

change attitudes toward Māori health and move forward in adopting culturally appropriate care

practices. More specifically the nursing workforce provides 80% of direct patient care, thus are in a

unique position to be the forefront of change in reducing health disparities experienced by Māori.

Incorporating cultural safety, patient advocacy, and Māori-centred models of care will support nurses

in adopting a new approach toward improving Māori health outcomes overall.

Keywords: health disparities; indigenous health; Māori health social policy; cultural safety; nursing

advocacy; Māori cultural care

M any countries across the globe experience

disparities in health between their indig-

enous and non-indigenous people (Stephens,

are a number of factors to consider, however this

essay focuses on a select few in order to explore

the complexity involved in ethnic disparities. Te

Porter, Nettleton, & Willis, 2006). In Aotearoa Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi) is the

(New Zealand) Indigenous Māori are the most primary source through which Māori are able to

marginalized and deprived ethnic group with the contest health disparities, however contradicting

poorest health status overall [Ministry of Health interpretations give rise to dispute over enforce-

(MOH), 2008]. Colonialism and numerous fac- ment of Oritetanga (British Citizenship Rights;

tors at the levels of individual patients, healthcare Humpage & Fleras, 2001). Nurses have a large

processes and the health system contribute to poor role to play in reducing the barriers that Māori

Māori health outcomes (Robson, 2004). There experience toward health services and improving

Volume 39, Issue 2, October 2011 CN 281

CN Katherine Evelyn Theunissen

Māori Ora (Māori holistic health and wellbeing) least one month’s delay between diagnosis and

overall (Wilson, 2006). treatment, which suggests that their treatment

British colonization brought new disease pathway is slower than that of non-Māori. Hill

and weapons of war that drastically increased et al. (2010) adds that patients were less likely

the mortality rates of Māori. Furthermore, set- to be treated with additional chemotherapy.

tlers dominated the economic and political Essentially this implies that these Māori patients

stature through methods of land confiscation were receiving a lower quality of treatment time-

and colonization, resulting in Māori inferiority liness and thoroughness overall, contributing to

(Ellison-Loschmann & Pearce, 2006). The sign- differential health outcomes in comparison to

ing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi resulted in Māori non-Māori patients. Consequently differential

submitting Kawanatanga (Article one) to the access and receipt leads to differential disease

Crown in exchange for Oritetanga (Article three) incidence, with Māori experiencing the poor-

and Rangatiratanga (Article two). Essentially, est health outcomes overall (Reid & Robson,

Kawanatanga allowed for the establishment 2006). It is evident that institutional discrimina-

of a constitutional government that to this day tion derived from the health system design has

controls the development of the New Zealand impacted on Māori health outcomes. Jansen et al.

health system (Broom et al., 2007). It is widely (2008, p. 19) proposes that this may be a result

understood that the health system was originally of having a ‘one service for all’ system that does

designed by non-Māori for non-Māori in accor- not appropriately accommodate for their cultural

dance with their own values, beliefs and objectives needs and unique perspectives of health.

(Ellison-Loschmann & Pearce, 2006). The discriminatory effect embedded in the

The ongoing crisis of Māori inferiority is health system directly impacts on the health

reflected by the prevailing disparities in health processes level by promoting bias attitudes of

outcomes and inadequate cultural representation healthcare professionals and giving rise to inter-

within the healthcare system (Reid & Robson, personal discrimination. Healthcare profession-

2006). The structural design of the system gives als’ bias attitudes result in differential treatment

rise to institutional discrimination in the form decision making (Jones, 2001). For example,

of differential access to healthcare and receipt of primary physicians are less likely to refer Māori

quality services (Hill et al., 2010). Māori experi- to specialist or surgical services in comparison to

ence a greater number of barriers to access, includ- non-Māori (Ellison-Loschmann & Pearce, 2006).

ing slower treatment processes, lengthy waiting A 2002/2003 survey revealed that Māori had the

lists and socioeconomic deprivation impacting highest number of self-reported racial discrimi-

on affordability and accessibility of services (i.e., natory experiences with healthcare professionals

transport costs or taking time off work; Jansen, (Jansen et al., 2008). Racial discrimination is a

Bacal, & Crengle, 2008). Cormack, Purdie, and breach of human and Indigenous rights (Harris

Robson (2007) identify that Māori are only 9% et al., 2006) that impacts on Māori receipt of

more likely to develop cancer but are 77% more quality health care and equitable health outcomes.

like to die from it in comparison to non-Māori. On an individual patient level, interpersonal

This is a good example of the implications that discrimination affects the attitudes that Māori

result from differential access experienced by have towards accessing health services and fosters

Māori. mistrust in the workforce to cater for their cul-

Similarly institutional discrimination gives rise tural needs (Jansen et al., 2008). Cram, Smith,

to differential quality of receipt of services pro- and Johnstone (2003) explain that Māori feel

vided. Hill et al. (2010) explains that Māori colon their cultural perspective of health is undermined

cancer patients were more likely to experience at by Pa- keha- dominance, and therefore exhibit

282 CN Volume 39, Issue 2, October 2011

The nurse’s role in improving health disparities CN

greater resistance toward trusting and engaging deaths, injury and disease for all New Zealanders

in services. Consequentially Māori are generally (Ministry of Social Development, 2001). In para-

dissatisfied with a health sector that lacks cultural dox, health inequities are defined as being avoid-

consideration on every level; that is from health able (Reid & Robson, 2006), thus social policy

system to healthcare workforce, through to the does not deliver what it promises. Literature

patient level (Jansen et al., 2008). Furthermore, argues that Te Tiriti, more specifically Oritetanga

Jansen et al. (2008) found that individual fears (British citizenship rights), has not been accu-

of being diagnosed with disease, facing conse- rately represented in social policy leading to dif-

quences of illness, losing privacy or experiencing ferential distribution of health resources and poor

whakama- also contribute to Māori avoidance of Māori health gains (Ellison-Loschmann & Pearce,

health services. 2006). This may be a result of the requirements

Essentially the explored issues are a few of for Māori representation in social policy to con-

the many factors causing Māori to experience fine by the structure of a health system originally

poorer health outcomes and a resultant life- developed for non-Māori.

expectancy similar to that achieved by non-Māori Furthermore, the debate about Oritetanga

20–30 years ago (Tobias, Blakely, Matheson, disputes whether ‘equal citizenship rights’ refer

Rasanathan, & Atkinson, 2009). Te Tiriti o to Māori having equal opportunities or outcomes

Waitangi provides a framework through which (Humpage & Fleras, 2001). One perspective

Māori are able to contest health disparities and identifies Oritetanga as enjoyment of promised

work towards achieving equitable health out- benefits resulting in equal outcomes. An opposing

comes. However, contradictory translations of the view identifies Oritetanga as equal opportunities

Māori and English versions of Te Tiriti o Waitangi because equality under the law means there should

have caused much debate regarding social rights be no distinction between Māori and non-Māori

as interpreted by Oritetanga in Article three (Barrett & Connolly-Stone, 1998). Even if the lat-

(Humpage & Fleras, 2001). ter interpretation is applied, Māori do not expe-

One argument contests that social rights were rience equal opportunities to quality and timely

not introduced to New Zealand law until long health care. This is a result of Māori experiencing

after Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed, therefore differential access and receipt of services caused

should not be included in Oritetanga (Barrett & by factors at the levels of institutional discrimi-

Connolly-Stone, 1998). However, the Court of nation, health care professional prejudice and the

Appeal declared Te Tiriti o Waitangi to be a liv- personal attitudes or beliefs of individual Māori

ing document, able to adjust to new circumstances (Hill et al., 2010).

rather than being confined to those that existed Essentially Aotearoa offers all residents equal

at the time of its signing (Te Puni Kökiri, 2001). access to healthcare services, including free

Furthermore, the notion of ‘equal citizenship priv- specialist and hospital care (Hill et al., 2010).

ileges’ implies that the Crown must ensure Māori However, while health care access may be equal

progress uniformly with non-Māori (Humpage & it is not equitable. Equity takes into account that

Fleras, 2001). In effect citizenship rights include different population groups experience different

social rights. The Royal Commission on Social social advantages/disadvantages and therefore may

Policy has since established three Te Tiriti prin- require different resourcing in order to achieve

ciples (partnership, participation and protection) similar health outcomes (Reid & Robson, 2006).

with the purpose of supporting Māori representa- Evidently health disparities reveal that Māori

tion in social policy (Oh, 2005). don’t enjoy the shared promises of Oritetanga as

Social policy aims to improve overall health out- guaranteed under Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Barrett &

comes and life-expectancy and prevent avoidable Connolly-Stone, 1998).

Volume 39, Issue 2, October 2011 CN 283

CN Katherine Evelyn Theunissen

Talbot and Verrinder (2010) suggest that on an ideology such as this then they are more

equity is achieved through social justice and the likely to act inappropriately towards Māori and

support of both policy and society to eliminate deliver culturally disempowering care, which

factors harmful to health. New Zealand social causes distrust and avoidance of health services

policy has a long journey ahead in the develop- (Ramsden, 2002).

ment of accurate representation of Māori culture In contrast, culturally safe nursing practice

in the healthcare system (Roorda & Peace, 2009). empowers Tangata Whenua through actions that

On a societal level, individual healthcare profes- acknowledge, nurture and value Māori cultural

sionals have the opportunity to change attitudes needs and rights (Polaschek, 1998). By perform-

towards Māori health and move forward in adopt- ing critical self-reflections on personal practice

ing culturally appropriate care practices. nurses are able to identify and resolve attitudes

Social justice exists when society acknowledges that put Māori at risk of cultural harm (Smye,

the unique worth of every individual and recog- Josewski, & Kendall, 2010). This also promotes

nizes equality and solidarity in achieving human open-mindedness, allowing nurses to empathise

rights (Humpage & Fleras, 2001). Where human with Māori beliefs of healing and health and

rights pertain to Oritetanga, Ma ¯ ori have the right arrive at good nursing decisions. Consequently

to be protected from discrimination and inequita- nurses are better equipped to provide culturally

ble health outcomes. Nurses have an ever expand- appropriate care that eradicates issues of differ-

ing role in reducing the misconduct that Ma ¯ ori ential treatment decision making and reinforces

endure as a result of inappropriate representation Māori trust in health services overall (Ramsden,

of cultural health perspectives in service (Ramsden, 2002). Daily application of culturally safe prac-

2002). The nursing workforce provides 80% of tice to nursing will improve individual Māori

direct patient care (Holloway, Baker, & Lumby, experiences and responses to healthcare, whilst on

2009); consequently nurses are in a unique posi- a greater scale contribute to the eventual elimi-

tion to personally be the forefront of change in the nation of discriminatory barriers to service and

levels of health processes and individual patients. improve Māori health outcomes.

Cultural safety or Kawa Whakaruruhau was The role of advocating for patients involves the

initially developed by a group of Māori nurses nurse becoming the ‘defender and promoter’ of

during the late 1980s in New Zealand. Their patient rights (Hyland, 2002, p. 473). In context,

aim was to raise awareness about the social this role provides nurses with the ability to defend

prejudices toward Māori people and change the against ethnic and racial discrimination that result

impact that this may have on the nursing care in differential treatment delivery. For example;

that they receive. Essentially they hoped for the nurses may advocate for Ma ¯ ori patients by ques-

Indigenous peoples’ voices to be heard and their tioning physicians who don’t make the necessary

cultural rights and needs to be accepted and safely referrals for specialist services. Constructive ques-

cared for (Polaschek, 1998). It is widely under- tioning may encourage physicians to recognize the

stood that the nurse’s personal cultural mindset harmful effects of their conscious or unconscious

influences his/her ability to connect with patients bias towards Ma ¯ ori (Ramsden, 2002). In turn

and form therapeutic relationships. For example, this may improve the quality and timeliness of

interpersonal racism is often based on an unac- healthcare treatment for Ma ¯ ori. On a larger scale,

ceptable societal prejudice that Māori are per- the massive nursing workforce has the strength

sonally responsible for their disparities due to in numbers to advocate on a health systems level

an inferiority of genes and lack of intelligence or (Jansen & Zwygart-Stauffacher, 2010), and there-

effort in caring for self (Reid & Robson, 2006). fore strive for consistency of Oritetanga in social

Therefore, if nurses are performing practice based policy and cultural consideration in health systems.

284 CN Volume 39, Issue 2, October 2011

The nurse’s role in improving health disparities CN

Jansen et al. (2008) suggest that nurse-led inter- It is evident that the complexity inherent in

ventions are the most suitable for providing health- health disparities between Māori and non-Māori

care that reduces inequalities, because they encompass runs deep into the core of the health care sys-

culturally tailored approaches within their practice. tem, reaches as wide as the health processes level

In essence, a Ma ¯ ori-centred approach to caring may and surfaces at the interactions with Māori indi-

support the nurse’s competency in providing cul- vidual patients. Contradicting interpretations

turally appropriate care (Barton & Wilson, 2008). of Te Tiriti o Waitangi impact on Māori ability

Nurses are able to seek Ma ¯ ori-centred guidance in to contest health disparities and seek equitable

Ma ¯ ori models of health such as; Te Whare Tapa Wha- Oritetanga. Furthermore, failure to consider

which outlines the four dimensions of Ma ¯ ori health Māori human, Indigenous and social rights in

and encourages holistic recognition of cultural needs; health care contributes to ongoing health ineq-

and He Korowai Oranga which is the Ma ¯ ori health uities in Aotearoa. The nursing workforce has a

strategy that supports Ma ¯ ori self-determination and major role to play in relinquishing Māori from

partnership with the Crown to achieve wha ¯ nau ora the health disparities that segregate them as a

(King & Turia, 2002). By having an understanding population. Incorporating cultural safety, patient

of health concepts developed by Ma ¯ ori for Ma ¯ ori advocacy and Māori-centred models of care will

eradicates the possibility of Pa ¯ keha¯ incorrectly repre- support nurses as they work towards improving

senting cultural principles (Cram et al., 2003). As a Māori health outcomes. In truth Māori people

result nurses will understand the Ma ¯ ori expectations need to be able to live comfortably as both Māori

and needs for cultural care. For example, nurses and citizens of Aotearoa in order to achieve

should understand that wha ¯ nau (family) participa- good health and a sense of meaningful wellbeing

tion in procedures is a preference for the majority of (Durie, 2005).

Ma ¯ ori and positively impacts on their recover over

all. Therefore a Ma ¯ ori-centred nursing care-plan References

should include wha ¯ nau participation in daily activi- Barrett, K., & Connolley-Stone, K. (1998). The

treaty of Waitangi and social policy. Social Policy

ties such as, showering the disabled Ma ¯ ori patient.

Journal of New Zealand, 11, 29–47.

Barton and Wilson (2008) provide an interesting

Barton, P., & Wilson, D. (2008). Te Kapunga

notion whereby building onto the existing strengths Putohe (the restless hands): A Māori centred

of Ma ¯ ori will enhance their attainment of improved nursing practice model. Nursing Praxis in New

health outcomes. Essentially wha- nau is one of Ma ¯ ori Zealand, 24(2), 6–15.

sources for strength, support and identity (King & Broom, D., Deed, B., Dew, K., Durie, M., Germov,

Turia, 2002). J., Kirkman, A., et al. (2007). Health in the con-

text of Aotearoa New Zealand. Melbourne, VIC:

Māori-Centred Models of Care Oxford University Press.

Cormack, D., Purdie, G., & Robson, B. (2007).

Te Whare Tapa Whā is the Māori model of

Cancer. In B. Robson & R. Harris (Eds.),

health that illustrates the four cornerstones Hauora: Mā ori standards of health IV: A study of

essential to their philosophy of holistic health the years 2000–2005 (pp. 103–118). Wellington:

and wellbeing. These include: physical, spiri- Te Ròpù Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pòmare.

tual, family and mental health. Cram, F., Smith, L., & Johnstone, W. (2003).

Mapping the themes of Māori talk about health.

He Korowai Oranga is New Zealand’s Māori Journal of New Zealand Medical Association, 116,

health strategy that aims to achieve wha- nau 1170.

ora (healthy families) by supporting Māori Durie, M. (2005). Mā ori Ora: The dynamics

families to reach maximum standards of holis- of Mā ori health. Melbourne, VIC: Oxford

tic health and wellbeing. (King & Turia, 2002) University Press.

Volume 39, Issue 2, October 2011 CN 285

CN Katherine Evelyn Theunissen

Ellison-Loschmann, L., & Pearce, N. (2006). effective partnership? Master’s thesis, University

Improving access to health care among New of Auckland, New Zealand.

Zealand’s Māori population. The American Polaschek, N. (1998). Cultural safety: A new con-

Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 612–617. cept in nursing people of different ethnicities,

Harris, R., Tobias, M., Jeffreys, M., Waldegrave, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27, 452–457.

K., Karlsen, S., & Nazroo, J. (2006). Racism Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing edu-

and health: The relationship between experi- cation in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Master’s

ence of racial discrimination and health in thesis, Victoria University of Wellington,

New Zealand. Social Science and Medicine, 63, New Zealand.

1428–1441. Reid, P., & Robson, B. (2006). Understanding health

Hill, S., Sarfati, D., Blakely, T., Robson, B., Purdie inequalities. In B. Robson & R. Harris (Eds.),

G & Kiwachi, I. (2010). Survival dispari- Hauora: Māori standards of health IV: A study of

ties in indigenous and non-Indigenous New the years 2000–2005 (pp. 3–10). Wellington: Te

Zealanders with colon cancer: The role of Ròpù Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pòmare.

patient comorbidity, treatment and health Robson, B. (2004). Economic determinants of Māori

service factors. Journal of Epidemiological health and disparities: A review for Te Röpü

Community Health, 64, 117–123. Tohutohu i te Hauora Tümatanui. Wellington:

Holloway, K., Baker, J., & Lumby, J. (2009). University of Otago, Wellington School of

Specialist nursing framework for New Zealand: Medicine.

A missing link in workforce planning. Policy, Roorda, M., & Peace, R. (2009). Challenges to

Politics and Nursing Practice, 10(4), 269–275. implementing good practice guidelines for

Humpage, L., & Fleras, A. (2001). Intersecting evaluation with Māori: A pākehā perspective.

discourses: Closing the gaps, social justice and Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 34, 73–89.

the Treaty of Waitangi. Social Policy Journal of Smye, V., Josewski, V., & Kendall, E. (2010).

New Zealand, 16, 37–53. Cultural safety: An overview. Canada: First

Hyland, D. (2002). An exploration of the relation- Nations, Inuit and Métis Advisory Committee

ship between patient autonomy and patient Mental Health Commission of Canada.

advocacy: Implications for nursing practice. Stephens, C., Porter, J., Nettleton, C., & Willis, R.

Nursing Ethics, 9(5), 472–482. (2006). Disappearing, displaced, and under-

Jansen, M., & Zwygart-Stauffacher, M. (2010). valued: A call to action for Indigenous health

Advanced practice nursing: Core concepts for pro- worldwide, The Lancet, 367, 2019–2028.

fessional role development. New York: Springer. Talbot, L., & Verrinder, G. (2010). Promoting health:

Jansen, P., Bacal, K., & Crengle, S. (2008). He The primary health care approach. Chatswood,

Ritenga Whakaaro: Mā ori experiences of health NSW: Elsevier.

services. Auckland: Mauri Ora Associates. Te Puni Kökiri. (2001). He Tirohanga ö Kawaki te

Jones, C. (2001). Invited commentary: ‘Race,’ rac- Tiriti o Waitangi: A guide to the principles of the

ism, and the practice of epidemiology. American treaty of Waitangi as expressed by the Courts and

Journal of Epidemiology, 154(4), 299–304. the Waitangi Tribunal (Overview). Wellington:

King, A., & Turia, T. (2002). He korowai oranga: Te Puni Kökiri.

Mā ori health strategy. Wellington: New Zealand Tobias, M., Blakely, T., Matheson, D., Rasanathan,

Ministry of Health. K., & Atkinson, J. (2009). Changing trends in

Ministry of Health. (2008). Nursing in New Indigenous inequalities in mortality: Lessons

Zealand: Mā ori nursing and workforce initiatives. from New Zealand. International Journal of

Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Health. Epidemiology, 38(6), 1711–1722.

Ministry of Social Development. (2001). The Wilson, D. (2006). The practice and politics of

social ldevelopment approach. Wellington: The Indigenous health nursing, Contemporary Nurse,

Ministry of Social Development. 22(2), 10–13.

Oh, M. (2005). The Treaty of Waitangi principles in

He Korowai Oranga – Mā ori health strategy: An Received 27 June 2011 Accepted 18 August 2011

286 CN Volume 39, Issue 2, October 2011

You might also like

- Primary Care ToolkitDocument46 pagesPrimary Care ToolkitSallie SkinnerNo ratings yet

- Culturally Competent Nursing Care and Promoting Diversity in Our Nursing WorkforceDocument6 pagesCulturally Competent Nursing Care and Promoting Diversity in Our Nursing WorkforceDiahsadnyawatiNo ratings yet

- Nursing Theories and Theorists Endterm Topic 01Document25 pagesNursing Theories and Theorists Endterm Topic 01CM PabilloNo ratings yet

- Management of DementiaDocument16 pagesManagement of DementiaAndris C BeatriceNo ratings yet

- The Epidemic of Opioids in AmericaDocument13 pagesThe Epidemic of Opioids in AmericaAliza SaddalNo ratings yet

- Certified Family Nurse Practitioner in West Palm Beach FL Resume Pamela ValleDocument3 pagesCertified Family Nurse Practitioner in West Palm Beach FL Resume Pamela VallePamelaValleNo ratings yet

- New Zealand )Document34 pagesNew Zealand )Tali1502No ratings yet

- Depression and The Elderly - FinalDocument8 pagesDepression and The Elderly - Finalapi-577539297No ratings yet

- Improving The Quality of Care in An Acute Care Facility Through RDocument88 pagesImproving The Quality of Care in An Acute Care Facility Through RNor-aine Salazar AccoyNo ratings yet

- Bullying: A Major Problem in NursingDocument5 pagesBullying: A Major Problem in NursingAshlee PowersNo ratings yet

- EpidemioDocument6 pagesEpidemioFlavian Costin NacladNo ratings yet

- Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine: Original ArticleDocument11 pagesJournal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine: Original Articleali sarjunipadangNo ratings yet

- Reducing Medical Error and Increasing Patient Safety: Richard Smith Editor, BMJDocument29 pagesReducing Medical Error and Increasing Patient Safety: Richard Smith Editor, BMJNOORAIMAH MURAHNo ratings yet

- Migration and TransnationalismDocument242 pagesMigration and TransnationalismNairaTalwarNo ratings yet

- Humanism, Nursing, Communication and Holistic Care: a Position Paper: Position PaperFrom EverandHumanism, Nursing, Communication and Holistic Care: a Position Paper: Position PaperNo ratings yet

- 15 Substance Related and Addictive DisordersDocument100 pages15 Substance Related and Addictive DisordersSashwini Dhevi100% (1)

- Nursing EmpowermentDocument8 pagesNursing EmpowermentmeityNo ratings yet

- Defining Professional Nursing Accountability A LitDocument5 pagesDefining Professional Nursing Accountability A LithusseinNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors Their Causative and Preventive Factors2.Doc 1Document11 pagesMedication Errors Their Causative and Preventive Factors2.Doc 1Mary MannNo ratings yet

- Forms of The Legends: Oral LiteratureDocument6 pagesForms of The Legends: Oral Literaturedurpaneusscribd100% (1)

- Fall Prevention Using TelemonitoringDocument14 pagesFall Prevention Using Telemonitoringapi-458433381No ratings yet

- National Medication Safety Guidelines Manual FinalDocument29 pagesNational Medication Safety Guidelines Manual FinalNur HidayatiNo ratings yet

- Lateralviolenceamongnurses Areviewoftheliterature 1Document13 pagesLateralviolenceamongnurses Areviewoftheliterature 1api-519721866No ratings yet

- Nurses Knowledge and Competence in Wound Management PDFDocument9 pagesNurses Knowledge and Competence in Wound Management PDFWawan Febri RamdaniNo ratings yet

- Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing PDFDocument5 pagesEthical Dilemmas in Nursing PDFtitiNo ratings yet

- DNP 800 Philosophy of NursingDocument7 pagesDNP 800 Philosophy of Nursingapi-247844148No ratings yet

- Guidelines For Cultural Safety, The Treaty of Waitangi, and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice PDFDocument24 pagesGuidelines For Cultural Safety, The Treaty of Waitangi, and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice PDFVerghese GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Cultural Safety, The Treaty of Waitangi, and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice PDFDocument24 pagesGuidelines For Cultural Safety, The Treaty of Waitangi, and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice PDFVerghese GeorgeNo ratings yet

- NMBA Case Studies Code of Conduct For Nurses and Code of Conduct For MidwivesDocument7 pagesNMBA Case Studies Code of Conduct For Nurses and Code of Conduct For Midwivestom doyleNo ratings yet

- Integrated Care With Indigenous Populations Considering The Role of Health Care Systems in Health DisparitiesDocument26 pagesIntegrated Care With Indigenous Populations Considering The Role of Health Care Systems in Health DisparitiesCale Holloway100% (1)

- Maori Culture StudyDocument3 pagesMaori Culture StudyAleida Moulton100% (2)

- Public Health EssayDocument5 pagesPublic Health Essayanon-105259100% (1)

- Professional Nursing Roles and ValuesDocument8 pagesProfessional Nursing Roles and Valuesjingle20No ratings yet

- Writing Nursing Essays and Case StudiesDocument4 pagesWriting Nursing Essays and Case StudiesShch ErNo ratings yet

- ParaphrasingDocument4 pagesParaphrasingDamla Özkapıcı100% (1)

- Wiggins Critical Pedagogy and Popular EducationDocument16 pagesWiggins Critical Pedagogy and Popular EducationmaribelNo ratings yet

- Health Care Disparities - Stereotyping and Unconscious BiasDocument39 pagesHealth Care Disparities - Stereotyping and Unconscious BiasCherica Oñate100% (1)

- Providing Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesProviding Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewLynette Pearce100% (1)

- Gene & Germ Line Therapy DifferencesDocument4 pagesGene & Germ Line Therapy DifferencesDaghan HacıarifNo ratings yet

- Psychological ChangesDocument36 pagesPsychological ChangesAndrei La MadridNo ratings yet

- Nurs21330 (Nursing Assess Me Nut Assignment)Document9 pagesNurs21330 (Nursing Assess Me Nut Assignment)Stella AshkerNo ratings yet

- The Public Image of The NurseDocument12 pagesThe Public Image of The NurseOke AdasenNo ratings yet

- Care Plan FinalDocument10 pagesCare Plan FinalAmanNo ratings yet

- Acute Kidney Injury: Mark BevanDocument42 pagesAcute Kidney Injury: Mark BevannasimhsNo ratings yet

- My Thesis Final VersionDocument41 pagesMy Thesis Final VersionBogdan ValentinNo ratings yet

- Nursing Sensitive Indicators Their RoleDocument3 pagesNursing Sensitive Indicators Their RolePuspita Eka Kurnia SariNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 018 Nursing Care PlanDocument8 pagesChapter - 018 Nursing Care PlansiewyonglimNo ratings yet

- Beyond Person Centred CareDocument11 pagesBeyond Person Centred CareJando Minggo SimonNo ratings yet

- Nurses Eat Their YoungDocument15 pagesNurses Eat Their Youngixora nNo ratings yet

- Realizing The Potential of Nurses Role in Genetics and Genomic Health Care - An Integrated Review of The LiteratureDocument5 pagesRealizing The Potential of Nurses Role in Genetics and Genomic Health Care - An Integrated Review of The LiteratureIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Theory of Interpersonal Relations-PeplauDocument35 pagesTheory of Interpersonal Relations-Peplaumel_pusag100% (1)

- Depression in Older AdultsDocument9 pagesDepression in Older Adultsapi-509881562No ratings yet

- Wound Case Study AssessmentDocument7 pagesWound Case Study Assessmentcass1526100% (2)

- Concept Analysis VulnerabilityDocument15 pagesConcept Analysis Vulnerabilityapi-525425941No ratings yet

- The Influence of The IOM - SubmitDocument9 pagesThe Influence of The IOM - SubmitKerry-Ann Brissett-SmellieNo ratings yet

- Week 2 Evolution of NursingDocument73 pagesWeek 2 Evolution of NursingAna PimentelNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Senior Capstone Reflection 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Senior Capstone Reflection 1Nathalee WalkerNo ratings yet

- Expanded and Extended Role of NurseDocument31 pagesExpanded and Extended Role of NurseMaria VarteNo ratings yet

- Geneticsgenomics in Nursing and Health CareDocument15 pagesGeneticsgenomics in Nursing and Health Careapi-215814528No ratings yet

- Nursing Philosophy Apa PaperDocument7 pagesNursing Philosophy Apa Paperapi-449016836No ratings yet

- NMC Code of Conduct PDFDocument5 pagesNMC Code of Conduct PDFico_isNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument10 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-433999236100% (1)

- Use of Sedation in Palliative CareDocument13 pagesUse of Sedation in Palliative Careuriel_rojas_41No ratings yet

- The Investigation and Analysis of Critical Incidents and Adverse Events in HealthcareDocument162 pagesThe Investigation and Analysis of Critical Incidents and Adverse Events in HealthcareBryan NguyenNo ratings yet

- Issue Analysis Paper Cultural Competence in Nursing ApplebachDocument18 pagesIssue Analysis Paper Cultural Competence in Nursing Applebachapi-283260051No ratings yet

- The Complete Medical Record and Electronic Charting: Chapter OutlineDocument25 pagesThe Complete Medical Record and Electronic Charting: Chapter OutlineabedelmasriNo ratings yet

- Improving Acheiving Health EquityDocument16 pagesImproving Acheiving Health EquityCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- MHF Legal Coercion Fact Sheets 2016Document40 pagesMHF Legal Coercion Fact Sheets 2016Cale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Health Literacy in ActionDocument10 pagesHealth Literacy in ActionCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Trends in Ischaemic Heart DiseaseDocument11 pagesTrends in Ischaemic Heart DiseaseCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument10 pagesJurnalAnggiaputrimkNo ratings yet

- Seeing The UnseenDocument8 pagesSeeing The UnseenCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- The Management of Stroke Patients. Conference of Experts With A Public Hearing. Mulhouse (France), 22 October 2008Document24 pagesThe Management of Stroke Patients. Conference of Experts With A Public Hearing. Mulhouse (France), 22 October 2008Cale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care Action Plan 0Document38 pagesPalliative Care Action Plan 0Cale HollowayNo ratings yet

- AM DocDocument1 pageAM DocCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Eff Ects of Self-Reported Racial Discrimination and DeprivationDocument6 pagesEff Ects of Self-Reported Racial Discrimination and DeprivationCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Principles of Care For A Child STUDENT NOTES AlbanyDocument19 pagesPrinciples of Care For A Child STUDENT NOTES AlbanyCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Dyall Marama2010 Article HealthAdvocacy CountingTheCostDocument15 pagesDyall Marama2010 Article HealthAdvocacy CountingTheCostCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Chai-Horton2010 Article ManagingPainInTheElderlyPopulaDocument9 pagesChai-Horton2010 Article ManagingPainInTheElderlyPopulaCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Cultural Safety No Turning BackDocument2 pagesCultural Safety No Turning BackCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Dyall Marama2010 Article HealthAdvocacy CountingTheCostDocument15 pagesDyall Marama2010 Article HealthAdvocacy CountingTheCostCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Fostering Students' Reflection About Bias in HealthcareDocument9 pagesFostering Students' Reflection About Bias in HealthcareCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Inequities in Life Expectancy Attributable To SmokingDocument11 pagesEthnic Inequities in Life Expectancy Attributable To SmokingCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Hauora IVDocument287 pagesHauora IVCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument10 pagesJurnalAnggiaputrimkNo ratings yet

- Hagan 2018Document4 pagesHagan 2018lusiNo ratings yet

- s41533 018 0091 9Document11 pagess41533 018 0091 9Cale HollowayNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Deinstitutionalisation in New Zealand: Exploring the Shift from Institutional to Community-Based Mental HealthcareDocument30 pagesThe Origins of Deinstitutionalisation in New Zealand: Exploring the Shift from Institutional to Community-Based Mental HealthcareCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Are Early Warning Scores Useful Predictors ForDocument11 pagesAre Early Warning Scores Useful Predictors ForCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Within Rural Tourism A Private Walkway On Banks Peninsula, New ZealandDocument11 pagesEntrepreneurship Within Rural Tourism A Private Walkway On Banks Peninsula, New ZealandmontannaroNo ratings yet

- Category NZ Halal 2Document7 pagesCategory NZ Halal 2sayajaswadiNo ratings yet

- The 2017 SSANSE Conference Report Can Be Accessed Here.Document4 pagesThe 2017 SSANSE Conference Report Can Be Accessed Here.umarNo ratings yet

- Flora and FaunaDocument18 pagesFlora and FaunaTatiana UrsuNo ratings yet

- Britton The Political Economy in The Third WorldDocument28 pagesBritton The Political Economy in The Third WorldVerónica RicartezNo ratings yet

- Maori Pre1700 DBR Army ListDocument2 pagesMaori Pre1700 DBR Army ListBeagle75No ratings yet

- Milford Sound, Fiordland - New Zealand's Fjordland ParadiseDocument2 pagesMilford Sound, Fiordland - New Zealand's Fjordland Paradisepssr2008No ratings yet

- The Chart Depics The Proportion of People Going To The Cinema Once A Month or More in An European Country BetDocument13 pagesThe Chart Depics The Proportion of People Going To The Cinema Once A Month or More in An European Country BetÁnh Ngọc NguyễnNo ratings yet

- New Zealand AnglDocument6 pagesNew Zealand AnglIuliaNo ratings yet

- SUBMISSION Historical FactsDocument7 pagesSUBMISSION Historical FactsJuana Atkins100% (1)

- HakaDocument1 pageHakarazzledazzlefaceNo ratings yet

- "Eeny Meeny Miny Moe" Catch Hegemony by The Toe-2015Document25 pages"Eeny Meeny Miny Moe" Catch Hegemony by The Toe-2015Jiayi XueNo ratings yet

- Māori Culture - WikipediaDocument38 pagesMāori Culture - WikipediaJai NairNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Hong Kong Visitor TrendsDocument5 pagesIntroduction to Hong Kong Visitor TrendsRoxi VmNo ratings yet

- Areas of Positive Growth in New Zealand: Group Members: Harinder KaurDocument31 pagesAreas of Positive Growth in New Zealand: Group Members: Harinder Kaurnnu princeNo ratings yet

- New Zealand - 11Document12 pagesNew Zealand - 11TaniNo ratings yet

- Pipiwharauroa Te Rawhiti Newsletter Volume 2 Issue 1Document13 pagesPipiwharauroa Te Rawhiti Newsletter Volume 2 Issue 1lellobotNo ratings yet

- 20160220-It Appears To Me Malcolm Turnbull Is Not Validly A Member of Parliament Nor Prime MinisterDocument55 pages20160220-It Appears To Me Malcolm Turnbull Is Not Validly A Member of Parliament Nor Prime MinisterGerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- Filipino Language SurveyDocument3 pagesFilipino Language Surveydomingojs233710No ratings yet

- Channel Tunnel Facts and HistoryDocument21 pagesChannel Tunnel Facts and Historyirma gochaleishviliNo ratings yet

- List of all schools sorted by school number (Includes closed schoolsDocument290 pagesList of all schools sorted by school number (Includes closed schoolsLakshay SidhNo ratings yet

- Matariki Karakia BookletDocument36 pagesMatariki Karakia Bookletsharon_t_kempNo ratings yet

- Topic: The Graph Below Shows: The Percentage of Immigrants Australia Five CountriesDocument8 pagesTopic: The Graph Below Shows: The Percentage of Immigrants Australia Five CountriesNguyễn Tiến Duy LinhNo ratings yet

- Pollock, Cultural Colonization and Textual BiculturalismDocument20 pagesPollock, Cultural Colonization and Textual BiculturalismCarola LalalaNo ratings yet

- Jian Yang-CV-First China VisitDocument8 pagesJian Yang-CV-First China VisitStuff Newsroom100% (1)

- The Treaty of WaitangiDocument15 pagesThe Treaty of WaitangiPatsy PickupNo ratings yet