Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Great Site Wor 1232

Great Site Wor 1232

Uploaded by

Darinka Orozco Altamirano0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views8 pagesOriginal Title

Great_Site_Wor_1232

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views8 pagesGreat Site Wor 1232

Great Site Wor 1232

Uploaded by

Darinka Orozco AltamiranoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

Perera

“...when the drama has been simplest, most genuine and

lit up by the joy of living, it has had its setting in the open.”

— Sheldon Cheney, The Open Air Theater, 1918

‘Ontdoor theaters have a uniquely close relation-

ship to the landscapes they inhabit, particularly to

the earth from which they are carved. Similar to

the earthworks of today's environmental artists,

they provide poignant insighe into how a culture

regards the landscape and nature, Exemplary out

door theaters — constructed in America’ estate

gardens, parks, campuses and development pro-

jects ~ can provide models for ereating memo-

rable relationships herween structure and sie

that reveal the unique character and spiritual

power ofa particular landscape.

Today we often associate outdoor theaters

with large commercial facilities that off

concerts to capacity crowds or historical dramas

to summer tourists, Although outdoor theaters

can be built at a fraction of the cost of similarly

sized indoor theaters, they frequently mimic the

characteristics of indoor theaters rather than cap-

talize on the unique opportunity of gathering

citizens together in the landscape

This disregard of the landscape setting in

theater

ign was notalways the case. During

q

the early 19008 “new drama” movement focused

sof an avant-garde group

of theatrical professionals, naturalists and design-

ers on creating open air theaters that were an

antidote to the increasing technical and commer-

cial concerns of indoor theaters, Influenced by

Greek artistic and democratic ideals, these the-

+ enthusiasts envisioned theaters as commu

nity strietires that weld enntrihnte to the

spiritual and civic well-being of American life by

aking the joys, good health and inspiration

of nature available to all

This civic and environmental idealism was still

evident in theaters buile in the 19208 and in the

Works Progress Administration theaters of the

19303 and "4os. After World War II, theater man-

agers began updating older theaters and buildi

new outdoor theaters with plastic seats, lig

structures, sound systems, concession facilities

and canopies to provide the amenities found in

interior theaters. The resultin

Sten 8, cushing Abie

obliteraed vistas and destroyed the topography,

‘vegetation and other natural patterns of the orig

‘nal landscape, This sift of design priorities from

‘he interpretation ofthe lndseape setting toa

fascination with technology ard physical comfort

has Fesulted in contemporary outdoor theaters

thatare not much different From indoor theaters

‘with athole in she root

“Tada, public concern for the preservation of

natural environments has macle it crucial that

..through the spoken work, the rendition of designers understand the opportunities and limi

: tations of placing stucturesin the landscape.

music, through song and dance the outdoor Inspite of these concerns, designe

: “ ‘contemporary suburb asa testament to the com

theater can contribute to mental, physical and. mercial pressure to disregard thelandscape

entirely. It is daunting to realize that structures

acceptany

spiritual growth, If itis healthful to exercise, designed woshowease artistic endeavors = sich

as outdo theaters ~ have also rleyaced the

work, play, and sleep in the open, itshould ——_landseapeto incdenal importance,

‘Notall the nowsis bad. Knights favorable

be even more beneficial to have our finer atmosphere” persists in many older outdoor the-

ters that continue to atract large audiences.

sensibilities unfolded in the same favorable The bestknown of these pre-World War I the-

aters is Colorado’s beautiful Red Rocks Theater,

atmosphere. designed by the architect Buraham Hoyt in 1936

and buileby the Givilian Conservation Corps

— Emerson Knight, Landscape architect, Despite what is considered a small seating capac

ity (9,000) that limits revenue, Red Rocks consis:

“Outdoor Theaters and Stadiums in the tontly wins Pollstar magazine's “best outdoor

concert vennie” survey of performers,

West,” in The Architect and Engineer, 1924 Tigh ralde thence eg ccm

Found sites, ancliences and performers frequently

adapt to hard seats, awkward sight lines, minimal

le

stage lighting, rain and overhead air traffic to

participate in cultural anc! eivie events that engage

the landscape, An understanding of these memo-

‘able older theaters can rekindle our commitment

twereating structures that incerpretand highlight

site’ unique natura character and, conse-

«quendy, ingpire reflection on how culture ein

interface with the beauty and rhythms of nature.

Locating theater precedents that successflly

cooly

‘vo American books on outdoor theaters: The

Open- Air Theatr (wos8) by theater crite Sheldon

‘Cheney and Oavdar Peasers (apr) by landscape

architect Frank Waugh. The majority ofthe

cease study theaters in these books are stil intact,

andn ative use, a testament ofthe appeal and

interpret their site is difficult since ther

endurance of thoughthully des

Both books diseuss expi

auldress their surrounding landseapes, indicating

pe.

With insights pertinent to contemporary

ly how the theaters

this eras focus on the land

design, Cheney's book differentiates two design

approaches. His “architectural theater” is most

clearly depicted in the book's images of the ago

Point Loma, Calif, Theosophical Society Greek

1. This type justaposes strong geometric

nse the surrounding landscape to reveal

‘charneterstis ofthe site that might otherwise

xo tnnoticed, such asasteep slope or an unusual

rock formation that is highlighted by placing

contrasting wall behind it. The Theosophical

Society ‘Theater’ white geometric forms contrast

sharply with the adjacent canyon and coastline,

focusing our attention on their rugged shapes

Like ts classical Greek precedent, the sill ntact

Theosophical Theater was site for its ve

from

the theater rather than by the appearance of the

theater itselfin the landscape.

Cheney's “nature theater” merges with the

landscape, giving the impression that itisa part

ofits natural surroundings, Witha stage back-

‘ground! of vegetation or the landscape beyond,

this theater type implies thar both performers and

ye merelya part ofthe scenery, Seating

is typically integrated into the topography, is

built from materials indigenous to the site and is

olen interrupted by vegetation or stones. Atone

of Cheney's examples, the Guerneville, C:

Bohemian Grove Theater the stage evolved

gradually on a redwood covered slope during the

Jate nineteenth century. Its unique vertical stage

still accommodates the annial Grove Plays, in

which actors appear on three different levels from.

fbchund the redwoods

‘The two California theaters derseribed in this

article, Mount Ielis Nature Theater ane! Mt

“Talmalpais Mountain Theater, do not fit neatly

into these categories, but instead exhibit proper

ses of both theater types. The formal coneepts af

both theaters began with simple geon

that,

with the geometries of the natural site. But chese

trieldeas

Cheney’ architectural theater, contrast

forms are modified, adjusted and distorted to

respond to the natural patterns ofthe particular

site. Many ofthese site-specifi adjustments are

apparent in the initial proposals, but significant

molifications were made during construction

when these schematic ideas were fine tuned to

the particulars of their immediate landscapes.

Alonger version f this sr

a, and the photog

Aston Gras ares pact ofa

fortheoming book ad exh

Ion, Cr Siete

Sition of Arise Ontdne

Thoaert Tse bok wil

inlide wey cine

salies of exemplary theaters

rane these sae wich

accompanying hiseiel and

contemporay photographs

Piling fr this see

‘wassuppoctedy the National

Enduninent orehe Ars,

Design Ares Penge, ad iy

the Universi California,

ese, hough its Com-

smi on Research ad the

Department of Landsape

Archivesture’ Fareand Pd

Rescirch asta

Temy Clements Gall Don-

also, Mey Calkinu and

Acne

4

Location: sloping east

‘ona summit 1320 ft

above sea level 12 miles

east of San Diego.

Designers: Richard

equa, architect;

Emerson Knight,

landscape architect.

Construction date:

1924.25,

Designated seats: 5,000

“otal capacity with seat-

ing on boulders

and wall: 8,000,

Bach Esster since 1925, approximately 7,000

people have attended sunrise services in a grand

theater atop Mt. Heli, the highest point in San

Diego County. This mountaintop had atracted

San Diego residents up a rough helix-shaped road

toa panoramic vista long before the theaters 125

dedication. Beginning in 1919, Paster worshipers

walked two anda half miles up the mountain to

crowd onto boulders and makeshift benches for

«simple service with a spectacular sunrise view,

‘One nearby resident, Mary Carpenter

‘Ywkey, came to the mountaintop Frequently co

‘meditate inthis majestic natural setting, When

Yawkey died in 1923 her daughter, Mary Yawkey

White, and son, Cyrus Carpenter Yawkey

decided to honor their mother by erecting:

nature theater on top of Mt. Helix for “inspira-

tion and public use.” White asked Ed Fletcher,

the local entrepreneur who owned the moun-

taintop, to sell the and. Instead, Fletcher

donated it and designated his 23-year-old son,

Ed Jr, to oversee construction ofthe project.

“The Yawkeys hired Richard Requa and Emer-

son Knight to design the theater. Requa wasa

revered loca architect who had designed many of

the buildings in Balboa Park. Knight, a San Fran-

ciseo landscape architect, had written extensively

oon outdoor theaters and designed several theaters

it Northern California. The collaboration went

well and they created a scheme that was distinct

from the environs yet inspired by the rugged

nature of he site

“Me, Heli rises from the mesas almost

2 perfect cone in outline to an atime of 500 ft.

Asite more inspiving, more raggealy picturesque,

more accessible or otherwise more perfeely fitted

toiits purpose eould hardly be found the world

cover. ..Bvery cut and fill, every rock formation

and boulder and even every plant and shrub most

be carefully considered so that perfect harmony

‘of parts and unity with the setting is secured and

maintained” (equa, 1925)

“The ewo men proposed asymmetrical, fan-

shaped scheme tobe buil of indigenous stone and

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Growing Up in Cities - Studies - Lynch, Kevin, 1918 - Banerjee, TDocument200 pagesGrowing Up in Cities - Studies - Lynch, Kevin, 1918 - Banerjee, TDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine - Google LibrosDocument1 pageCambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine - Google LibrosDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- Qué Ciudad Queremos para MañanaDocument35 pagesQué Ciudad Queremos para MañanaDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet

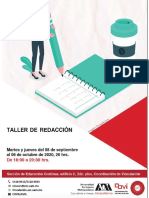

- Taller de RedacciónDocument72 pagesTaller de RedacciónDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- Joan Jean "Capítulo X. Luces de La Ciudad Alumbrado Callejero y Vida Nocturna" en La Esencia Del Estilo, Historia de La Invención de LaDocument7 pagesJoan Jean "Capítulo X. Luces de La Ciudad Alumbrado Callejero y Vida Nocturna" en La Esencia Del Estilo, Historia de La Invención de LaDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- BolanosVegaRamirezCabreraQuirozSiller TlaltencounecositemahidricourbanoDocument376 pagesBolanosVegaRamirezCabreraQuirozSiller TlaltencounecositemahidricourbanoDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- BolanosVegaRamirezCabreraQuirozSiller Presentacion TlaltencoDocument164 pagesBolanosVegaRamirezCabreraQuirozSiller Presentacion TlaltencoDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- Egas Claudia PDFDocument86 pagesEgas Claudia PDFDarinka Orozco AltamiranoNo ratings yet