Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jaypaul V. Cayeux 1954 MR 181

Uploaded by

Milazar NigelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jaypaul V. Cayeux 1954 MR 181

Uploaded by

Milazar NigelCopyright:

Available Formats

JAYPAUL v.

CAYEUX

1954 MR 181

Sir Francis Herchenroder*, CJ and

Osman, J

This is is an appeal from a judgment of the District Magistrate of Flacq

whereby he held that he had no jurisdiction to try a possessory action entered

by the appellant against the respondent. The plaint, after amendment, averred

that the plaintiff was the owner by title of a plot of land of one acre and

eighteen perches situate at Clémencia, that the plaintiff had been in

possession of the land for one full year previous to the disturbance of such

possession by the defendant on the 2nd February, 1953. The action was entered

on the 20th February, 1953. (The date of the alleged disturbance is stated in

the plaint to be the 22nd February, 1953, but it was agreed between counsel

that this was a clerical error for the 2nd February, 1953).

The defendant denied the facts alleged in the plaint. He pleaded that he

was the owner by title of the land in suit which was worth more than Rs 1,000

and that, consequently, the magistrate had no jurisdiction to try the question

of ownership of the land. Mr. Attorney Ducasse and Mr. Dubruel de Broglio who

appeared, respectively, for the plaintiff and the defendant in the court below

were agreed that the action was a possessory action and that the land in

question was worth more than Rs 1,000. But while Mr. Ducasse contended that,

the action being a possessory action, the magistrate had jurisdiction to try

it, whatever might be the value of the land, Mr. Dubruel submitted that he had

not by reason of the provision contained in section 120(3) of the Courts

Ordinance.

After hearing the respective contentions, the magistrate upheld the plea

that he had no jurisdiction to try the case which he dismissed.

The action was based upon section 120 of the Courts Ordinance (formerly

section 9 of Ordinance No. 22 of 1888) the material parts of which, for the

purposes of this appeal, run as follows:

120(1). The Magistrate shall have jurisdiction in possessory actions

concerning any land… or other real property… including actions where such

property… exceeds one thousand rupees in value when the plaintiff claims to

be maintained or restored to the quiet enjoyment and possession of such

property:

Provided (a) the possessory action has been entered during one year from

the imputed trespass, and (b) the plaintiff has been in quiet possession

for one full year at least.

(2)…

(3) When the value of the property… concerning which a possessory action is

brought does not exceed one thousand rupees, the Magistrate may go into and

decide upon the question of ownership if same be raised.

Mr. Avrillon, who appeared for the appellant, submitted that this

provision was borrowed from article 23 of the Code of Civil Procedure which

runs thus:

Les actions possessoires ne seront recevables qu’autant qu’elles auront été

formées, dans l’année du trouble, par ceux qui, depuis une année au moins,

étaient en possession paisible par eux ou les leurs, à titre non précaire.

He also referred to articles 24 and 25 which read:

24. Si la possession ou le trouble sont deniés, l’enquête qui sera ordonnée

ne pourra porter sur le fond du droit.

25. Le possessoire et le pétitoire ne seront jamais cumulés.

The legal position on the subject in France is tersely summed up in notes

23, 35 and 40, Vo. Action Possessoire, in Encyclopédie Dalloz, Droit Civil,

Vol. 1:

23. Le principe de la séparation du possessoire et du pétitoire est la

condition d’efficacité de la protection possessoire comme défense avancée

de la propriété. Il assure l’autonomie de la protection possessoire par

rapport à celle de la propriété; le débat ne pouvant être déplacé d’un

terrain sur l’autre, la possession sera garantie, quelle que soit la

situation véritable de la propriété. Il permet le règlement rapide et

préalable de la question possessoire, la propriété étant réservée et

l’élimination des difficultés touchant au fond du droit favorisant la

simplification de la procédure.

35. Le débat possessoire doit suivre son cours, sur le terrain qui lui est

propre, sans qu’aucune entrave puisse y être apportée pour des raisons

tirées du fond du droit. Le possesseur doit être protégé, encore que l’on

soit certain qu’il n’est pas propriétaire. Il en résulte que, si le

défendeur soulève une exception tirée du fond du droit, le juge du

possessoire ne doit pas s’y arrêter, et se dessaisir, comme le ferait un

juge des référés en présence d’une contestation sérieuse; il doit

s’abstenir de l’examiner, et statuer sur la possession… (G.P. 1929.2.729

and note: cf. however G.P. 1932.2.60).

40… . les titres peuvent être utilisés pour fixer le sens et la portée des

faits matériels, pour éclairer et colorer la possession… Il n’est pas

interdit au juge du possessoire d’examiner les titres produits par les

parties, à charge de les apprécier au seul point de vue du possessoire, et

d’y rechercher, non le droit mais le caractère de la possession invoquée…

(D. 1946.133).

Before the enactment of section 9 of Ordinance No. 22 of 1888 the law on

the subject was contained in section 6 of Ordinance No. 34 of 1852 which ran as

follows:

“The District Magistrates shall… in their respective courts have

jurisdiction in all actions of ejectment against the occupiers of any

lands… or any other right arising out of real property when the right of

occupation only shall be in question, unless it shall be shown by the

defendant that such right of occupation during the term or period as to

which it shall be in dispute is to him of a clear value of more than £100;

and whatever may be the value of the right in question the District

Magistrates are hereby empowered to take cognizance of the case so far as

to secure to the plaintiff, or restore him to, a quiet enjoyment and

possession thereof until such right has been finally adjudicated on by the

Supreme Court, provided always such possessory action has been entered

before the District Magistrate within one year from the imputed trespass

and the plaintiff thus occupying or claiming to occupy has been in quiet

possession for one full year at least.”

That provision has received judicial consideration by this court in the

following cases: Murray v. Rahiman, [1863 MR,]136; Brue v. Duval, [1864 MR 62];

Ardé v. Baissac, [1864 MR 83]; Bardin v. Brousse de Gersigny, [1864 MR 90]; Florens

v. Michel, [1864 MR 126]; Macquet v. Cantin, [1865 MR 67]; and Burguez v. Régnier,

[1877 MR 160].

The conclusions to be drawn from those cases may be stated under four

heads:

(1) A party who claims to be the owner of a plot of land of which he

has been in possession for one full year at least, is entitled, in an

action to get rid of a trespasser who disturbs his possession, to rest

his case solely upon the fact of his quiet possession animo domini. He is

not bound, in every instance, to set up his title in a petitory action

before the competent court. A possessory action will lie even though the

possessor may ultimately be found not to be entitled to the property.

(2) In order that a District Magistrate should have jurisdiction to try

a possessory action, the plaintiff must invoke lawful possession for one

full year at least before the disturbance complained of took place, and

the action must be brought within one year of the disturbance.

(3) A District Magistrate trying a possessory action has no

jurisdiction to decide upon questions of title to the land in suit; but

he may nevertheless look at the plaintiff’s title, if there is one, to

ascertain, not whether the title is unimpeachable, but whether it throws

any light upon the nature of the plaintiff’s possession.

(4) A plaintiff alleging possession for a year at least is prima facie

entitled to apply to the District Magistrate to maintain him in

possession; and it is the duty of the magistrate to satisfy himself

whether the fact alleged is true and, if so satisfied, to maintain the

plaintiff in his possession and not to allow him to be summarily ejected.

Mention may also be made, here of the case of Nina v. Vert, [1880 MR 28],

where Cox, J. said, with reference to section 6 of Ordinance No. 34 of 1852:

The second part of the article is borrowed from the French law of Actions

Possessoires, as established by article 23 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

In such cases whatever may be the value of the right of occupation, one who

has possessed for upwards of one year may ask the Magistrate to secure and

restore to him the quiet enjoyment of the subject. The jurisdiction is

there conditioned upon (1) possession for one whole year by the plaintiff

(2) action brought within one year from the trespass complained of.

While not disputing that the action was a possessory action, Mr. Dubruel

for the respondent contended that the questions of ownership and possession

were so intimately mixed up in the case that it was impossible for the

magistrate to decide the question of possession without going into that of

ownership and that, he said, the magistrate was debarred from doing. Mr.

Dubruel submitted an a contrario argument derived from section 120 (3) of the

Courts Ordinance. He urged that the position after the enactment of section 9

of Ordinance No. 22 of 1888 was this: when in a possessory action the defendant

pleaded that he was the owner of the property in question, and that property

was worth more than one thousand rupees, the jurisdiction of the magistrate was

ousted altogether.

Mr. Dubruel referred to Teeluckdharry v. Nundlall, [1951 MR,]110, and

Brasse v. Léonide, [1953 MR 137]; but we may say at once that in our view neither

case finds its application here: they were both actions in ejectment enterred

under sections 118 and 116, respectively, of the Courts Ordinance, and not

possessory actions under section 120(1).

It will be observed that while under section 6 of Ordinance No. 34 of

1852 the magistrate’s jurisdiction was confined in all cases to adjucating on

the question of occupation or possession, section 9 (3) of Ordinance No. 22 of

1888 conferred upon the magistrate jurisdiction, in a possessory action, to go

into and decide the question of ownership of the land (where that question was

raised) if the land was not worth more than one thousand rupees. We do not

think that that provision (which is now section 120 (3) of the Courts

Ordinance) means, or was intended to mean, a contrario, that when the value of

the property concerning which a possessory action is brought exceeds one

thousand rupees, and the question of the ownership of the property is raised by

the defendant the magistrate has no jurisdiction to try the case. We think that

the object of the provision was to create a departure from the principle

embodied in article 25 of the Code of Civil Procedure cited above in the case

of property of a value not exceeding one thousand rupees, and to obviate the

necessity for the defendant in a possessory action concerning such property who

desired to have the question of the ownership thereof decided in that action to

enter a new action for the purpose after the possessory action had been

disposed of (cf. art. 27, C.C.P.).

In his judgment the magistrate stated that both plaintiff and defendant

were claiming the ownership of the land and that accordingly he could not

decide whether the defendant’s occupation of the land was unlawful or not

without deciding upon the question of ownership of the land which he had no

power to do as it was worth more than one thousand rupees. We think that the

magistrate misdirected himself. Although the plaintiff mentioned in his plaint

that he was the owner of the land in suit by title, it is clear, and that was

common ground in the court below, that by his action he claimed to be

maintained in the quiet possession of the land of which he had been in

possession for one full year. That being so, it was not necessary for the

magistrate to look into the respective titles of the parties and decide upon

their validity. It was his duty to satisfy himself whether, as averred in the

plaint, the plaintiff had been in possession of the land for one full year at

least before the imputed trespass and whether the action had been entered

within one year of that trespass. He had also, of course, to ascertain whether

the plaintiff’s possession was of the character and nature required by law. We

hold, therefore, that the magistrate was wrong to decide that he had no

jurisdiction to try the case. We reverse his decision and remit the case back

to the District Court of Flacq to be heard on the merits. The respondent will

pay the costs of this appeal.

Appellant: Attorney V Ducasse

Avrillon, of Counsel

Respondent: Attorney F A Bradshaw

Dubruel de Broglio, of Counsel

RECORD NO. 1708

You might also like

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Legal OpinionDocument5 pagesLegal Opinionmarvinnino888No ratings yet

- Cloridor Vs Naltoka: 1983 MR 117 1983 SCJ 234Document4 pagesCloridor Vs Naltoka: 1983 MR 117 1983 SCJ 234Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Edwick CaseDocument11 pagesEdwick CaseadasNo ratings yet

- Quimson VS SuarezDocument4 pagesQuimson VS SuarezRvic CivrNo ratings yet

- 1989 C L C 191Document4 pages1989 C L C 191Ahmed KhatriNo ratings yet

- Property Digest - AccessionDocument23 pagesProperty Digest - AccessionKvyn HonoridezNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 183543 National Housing vs. Manila SeedlingDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 183543 National Housing vs. Manila SeedlingSheridan AnaretaNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondent: First DivisionDocument6 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondent: First DivisionKate SchuNo ratings yet

- The Law On Adverse Possession in KenyaDocument21 pagesThe Law On Adverse Possession in KenyaFREDRICK WAREGANo ratings yet

- DELA CRUZ Vs CADocument4 pagesDELA CRUZ Vs CAjamesonuy100% (1)

- Right of Retention Does Not Allow Exclusive Use of FruitsDocument4 pagesRight of Retention Does Not Allow Exclusive Use of FruitsEunice Valeriano GuadalopeNo ratings yet

- ELAND PHIL INC. v. GARCIADocument4 pagesELAND PHIL INC. v. GARCIASteven AveNo ratings yet

- CD 13Document40 pagesCD 13chelloNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Bruce and Lawrence For Appellant. W. L. Wright For AppelleeDocument3 pagesSupreme Court: Bruce and Lawrence For Appellant. W. L. Wright For AppelleeLuna KimNo ratings yet

- Period, The Mortgagee's Remedy Is An Ordinary Action For Recovery of Possession. in Support of This PropositionDocument8 pagesPeriod, The Mortgagee's Remedy Is An Ordinary Action For Recovery of Possession. in Support of This PropositionAisha TejadaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-21381Document4 pagesG.R. No. L-21381anon_460782703No ratings yet

- Court Rules in Favor of Easement RightsDocument32 pagesCourt Rules in Favor of Easement RightsBianca Viel Tombo CaligaganNo ratings yet

- Juris in EjectmentDocument19 pagesJuris in Ejectmentromeo n bartolomeNo ratings yet

- 8) Ortiz v. Kayanan PDFDocument3 pages8) Ortiz v. Kayanan PDFhectorjrNo ratings yet

- 01-Acuna v. CaluagDocument5 pages01-Acuna v. CaluagryanmeinNo ratings yet

- Civpro Finals DigestDocument96 pagesCivpro Finals DigestElla B.100% (1)

- Art. 427-439 Ownership NotesDocument14 pagesArt. 427-439 Ownership NotesArvy AgustinNo ratings yet

- Research On Accion PublicianaDocument5 pagesResearch On Accion PublicianaJiva LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Court upholds order placing buyer in possession of foreclosed landDocument2 pagesCourt upholds order placing buyer in possession of foreclosed landJosephine BercesNo ratings yet

- Manotok Realty v. CADocument5 pagesManotok Realty v. CAdave bermilNo ratings yet

- Cases Discussing Elements and Definition of ToleranceDocument19 pagesCases Discussing Elements and Definition of ToleranceRalna Dyan FloranoNo ratings yet

- Titong v. Court of AppealsDocument12 pagesTitong v. Court of Appealsnewin12No ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-5227 October 25, 1909Document4 pagesG.R. No. L-5227 October 25, 1909Ronil ArbisNo ratings yet

- Ali Akang Vs - Municipality of Isulan, Sultan Kudarat Province FactsDocument9 pagesAli Akang Vs - Municipality of Isulan, Sultan Kudarat Province FactsCrystal Joy MalizonNo ratings yet

- Acuna v. ED CALUAGDocument8 pagesAcuna v. ED CALUAGMarefel AnoraNo ratings yet

- Land Titles and Deeds: Key ConceptsDocument8 pagesLand Titles and Deeds: Key ConceptsHanabishi RekkaNo ratings yet

- Tumalad vs. Vicencio, 41 SCRA 143Document6 pagesTumalad vs. Vicencio, 41 SCRA 143Reny Marionelle BayaniNo ratings yet

- Solid Manila Corp. v. Bio Hong Trading Co., Inc.Document10 pagesSolid Manila Corp. v. Bio Hong Trading Co., Inc.Macy YbanezNo ratings yet

- Answer With Grounds of Defense To An Unlawful DetainerDocument5 pagesAnswer With Grounds of Defense To An Unlawful DetainerNicNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Legal Principles OwnershipDocument11 pagesModule 3 Legal Principles OwnershipKristian Romeo NapiñasNo ratings yet

- 2nd Wave For DigestDocument35 pages2nd Wave For DigestVanzNo ratings yet

- GR L-19967Document4 pagesGR L-19967Henson MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Prop-1-Damian Ignacio v. Elias Hilaro, Et - Al., 76 Phil 605, GR No. L-175, Apr 30, 1946Document4 pagesProp-1-Damian Ignacio v. Elias Hilaro, Et - Al., 76 Phil 605, GR No. L-175, Apr 30, 1946Galilee RomasantaNo ratings yet

- Forcible Entry Until Contempt CasesDocument87 pagesForcible Entry Until Contempt CasesBarvi GoducoNo ratings yet

- Rights of Land and Building OwnersDocument3 pagesRights of Land and Building OwnersEunice NavarroNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 106473: Gilberto C. Alfafara For Petitioner. Bernadito A. Florido For Private RespondentDocument6 pagesG.R. No. 106473: Gilberto C. Alfafara For Petitioner. Bernadito A. Florido For Private RespondentJM EnguitoNo ratings yet

- Isidro vs. CA GR 105586, December 15, 1993Document7 pagesIsidro vs. CA GR 105586, December 15, 1993pennelope lausanNo ratings yet

- Manotok Realty vs Honorable TecsonDocument6 pagesManotok Realty vs Honorable Tecsonmarie janNo ratings yet

- Grant of Title Land RegistrationDocument2 pagesGrant of Title Land RegistrationalexjalecoNo ratings yet

- September 30 Property 1Document52 pagesSeptember 30 Property 1Shanell EscalonaNo ratings yet

- Property dispute over 90 hectares of land in CaviteDocument52 pagesProperty dispute over 90 hectares of land in CaviteShanell EscalonaNo ratings yet

- Jamero 7thWeekCaseDigest PropertyandLandLawDocument16 pagesJamero 7thWeekCaseDigest PropertyandLandLawAubrinary JohnNo ratings yet

- Facts: 1. Technogas Phils. Manufacturing Corp. VS. CA 268 SCRA 5 DigestDocument100 pagesFacts: 1. Technogas Phils. Manufacturing Corp. VS. CA 268 SCRA 5 DigestElbert TramsNo ratings yet

- Gomez Vs GealoneDocument8 pagesGomez Vs GealoneFred Michael L. GoNo ratings yet

- Court Overturns Receivership Order in Property DisputeDocument3 pagesCourt Overturns Receivership Order in Property DisputeHv EstokNo ratings yet

- for Philippine Supreme Court Case on Mortgage ForeclosureDocument5 pagesfor Philippine Supreme Court Case on Mortgage ForeclosureErik CelinoNo ratings yet

- ADVERSE POSSESSION by SMT SRIDEVI SHANKER PRL JCJ SIRICILLADocument15 pagesADVERSE POSSESSION by SMT SRIDEVI SHANKER PRL JCJ SIRICILLAParitosh Rachna GargNo ratings yet

- 18 ObliconDocument6 pages18 ObliconQuiquiNo ratings yet

- Cases On OwnershipDocument7 pagesCases On Ownershipsylvia patriciaNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction CasesDocument25 pagesJurisdiction CasesAerwin AbesamisNo ratings yet

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents Herminio L. Ruiz Vicente D. Millora Romero A. YuDocument7 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents Herminio L. Ruiz Vicente D. Millora Romero A. YuEunice NavarroNo ratings yet

- Manila Electric Company Land Registration CaseDocument2 pagesManila Electric Company Land Registration CaseSonnyNo ratings yet

- 6 Isaguirre Vs de Lara PropertyDocument17 pages6 Isaguirre Vs de Lara Propertykikhay11No ratings yet

- Ethics and Law, and Ethics As Law (PDFDrive)Document386 pagesEthics and Law, and Ethics As Law (PDFDrive)Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Hurnam SCJ 79Document7 pagesHurnam SCJ 79Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Gender Stats Yr20 190721Document29 pagesGender Stats Yr20 190721Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Divided Loyalties? The Lawyer'S Simultaneous Duty To Client and The Courts. Monash Guest Lecture in Ethics: 20 November 2009Document16 pagesDivided Loyalties? The Lawyer'S Simultaneous Duty To Client and The Courts. Monash Guest Lecture in Ethics: 20 November 2009Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Shell Mauritius Dismissal Appeal RejectedDocument13 pagesShell Mauritius Dismissal Appeal RejectedMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Employment Relations Act 2008 summaryDocument161 pagesEmployment Relations Act 2008 summaryMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Revist@ - : MercatoriaDocument15 pagesRevist@ - : MercatoriaMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Re Geemul A Barrister 1992 MR 140Document25 pagesRe Geemul A Barrister 1992 MR 140Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- NATIONAL BANK OF CANADA V IBL LTD & ORSDocument7 pagesNATIONAL BANK OF CANADA V IBL LTD & ORSMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Court Restricts Church Loudspeaker UseDocument3 pagesCourt Restricts Church Loudspeaker UseMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- ADAMAS LIMITED V YONG TING PING HOW FOK CHEUNG (MRS) 2010 PRV 22Document18 pagesADAMAS LIMITED V YONG TING PING HOW FOK CHEUNG (MRS) 2010 PRV 22Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Res Judicata PrincipleDocument4 pagesRes Judicata PrincipleMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Ramgoolam V Speaker of National Assembly 1993 MR 269Document3 pagesRamgoolam V Speaker of National Assembly 1993 MR 269Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Employment Relations Act 2008Document125 pagesEmployment Relations Act 2008PoojaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court International Arbitration Claims Rules 2013Document25 pagesSupreme Court International Arbitration Claims Rules 2013Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Pasnin Marie Diana Natacha (Born Lamto) V Pasnin Nathanael and Ors-1Document5 pagesPasnin Marie Diana Natacha (Born Lamto) V Pasnin Nathanael and Ors-1Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- RAFFIQUE ABDOOL SIDDIQUE V THE STATE and ORS 2015 SCJ 359Document2 pagesRAFFIQUE ABDOOL SIDDIQUE V THE STATE and ORS 2015 SCJ 359Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- POLICE V SWEE STELIO JEANDocument4 pagesPOLICE V SWEE STELIO JEANMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Police V Ste Marie David AlexandreDocument9 pagesPolice V Ste Marie David AlexandreMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- RAVINA JENIFER V SAMUEL IZADocument4 pagesRAVINA JENIFER V SAMUEL IZAMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Bail-Luco PhillippeDocument8 pagesBail-Luco PhillippeMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Police V Hypolite Ange MichelDocument6 pagesPolice V Hypolite Ange MichelMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Police V Plaiche Adele Jayne LysaDocument5 pagesPolice V Plaiche Adele Jayne LysaMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- (Precedent) - CIVIL PROCEDURE FINAL Resit EXAMSDocument1 page(Precedent) - CIVIL PROCEDURE FINAL Resit EXAMSMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Zaragoza V MadeleineDocument4 pagesZaragoza V MadeleineMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- No 13 - THE ACQUISITIVE PRESCRIPTION ACT 2018Document9 pagesNo 13 - THE ACQUISITIVE PRESCRIPTION ACT 2018Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- AUGUSTE F V LEONG LONE C W SCJ 213Document6 pagesAUGUSTE F V LEONG LONE C W SCJ 213Milazar NigelNo ratings yet

- 8 - Anesthesia and Patient SafetyDocument16 pages8 - Anesthesia and Patient SafetyMilazar NigelNo ratings yet

- Cost and Quality ManagementDocument8 pagesCost and Quality ManagementRanjini K NairNo ratings yet

- iC60L Circuit Breakers (Curve B, C, K, Z)Document1 pageiC60L Circuit Breakers (Curve B, C, K, Z)Diego PeñaNo ratings yet

- PSY290 Presentation 2Document3 pagesPSY290 Presentation 2kacaribuantonNo ratings yet

- C.J LetterDocument2 pagesC.J LetterIan WainainaNo ratings yet

- BS 3921-1985 Specification For Clay Bricks PDFDocument31 pagesBS 3921-1985 Specification For Clay Bricks PDFLici001100% (4)

- Chap 21 Machining FundamentalsDocument87 pagesChap 21 Machining FundamentalsLê Văn HòaNo ratings yet

- VOLVO G746B MOTOR GRADER Service Repair Manual PDFDocument14 pagesVOLVO G746B MOTOR GRADER Service Repair Manual PDFsekfsekmddde33% (3)

- OM-Module-5 (PM)Document25 pagesOM-Module-5 (PM)Absar SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Noise - LightroomDocument2 pagesNoise - LightroomLauraNo ratings yet

- Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) andDocument10 pagesOrganizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) andInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- RESIDENT NMC - Declaration - Form - Revised - 2020-2021Document6 pagesRESIDENT NMC - Declaration - Form - Revised - 2020-2021Riya TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Section 1 Quiz: Reduced Maintenance Real-World Modeling Both ( ) NoneDocument50 pagesSection 1 Quiz: Reduced Maintenance Real-World Modeling Both ( ) NoneNikolay100% (2)

- Indonesia Trade Report Highlights Recovery & OutlookDocument27 pagesIndonesia Trade Report Highlights Recovery & OutlookkennydoggyuNo ratings yet

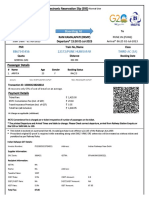

- 22172/pune Humsafar Third Ac (3A)Document2 pages22172/pune Humsafar Third Ac (3A)VISHAL SARSWATNo ratings yet

- Reference Letter No 2Document5 pagesReference Letter No 2Madhavi PatnamNo ratings yet

- Gauge BlockDocument32 pagesGauge Blocksava88100% (1)

- TaxDocument9 pagesTaxRossette AnaNo ratings yet

- Quotation: Spray Extraction Carpet Cleaner Model No: PUZZI 8/1 Technical DataDocument8 pagesQuotation: Spray Extraction Carpet Cleaner Model No: PUZZI 8/1 Technical DataMalahayati ZamzamNo ratings yet

- List of All Premium Contents, We've Provided. - TelegraphDocument5 pagesList of All Premium Contents, We've Provided. - TelegraphARANIABDNo ratings yet

- SOP 1-023 Rev. 16 EPA 547 GlyphosateDocument20 pagesSOP 1-023 Rev. 16 EPA 547 GlyphosateMarco QuinoNo ratings yet

- Airport Engineering Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument1 pageAirport Engineering Multiple Choice QuestionsengineeringmcqsNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of 4-2 Compressor For Arithmetic ApplicationDocument4 pagesDesign and Analysis of 4-2 Compressor For Arithmetic ApplicationGaurav PatilNo ratings yet

- 05.10.20 - SR - CO-SUPERCHAINA - Jee - MAIN - CTM-8 - KEY & SOL PDFDocument8 pages05.10.20 - SR - CO-SUPERCHAINA - Jee - MAIN - CTM-8 - KEY & SOL PDFManju ReddyNo ratings yet

- B757-767 Series: by Flightfactor and Steptosky For X-Plane 11.35+ Produced by VmaxDocument35 pagesB757-767 Series: by Flightfactor and Steptosky For X-Plane 11.35+ Produced by VmaxDave91No ratings yet

- Fall 22-23 COA Lecture-5 Processor Status & FLAGS RegisterDocument25 pagesFall 22-23 COA Lecture-5 Processor Status & FLAGS RegisterFaysal Ahmed SarkarNo ratings yet

- GEO Center Catalog enDocument20 pagesGEO Center Catalog enEdward KuantanNo ratings yet

- Principles of ManagementDocument7 pagesPrinciples of ManagementHarshit Rajput100% (1)

- Hershey's Milk Shake ProjectDocument20 pagesHershey's Milk Shake ProjectSarvesh MundhadaNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis WhelanDocument5 pagesCase Analysis WhelanRakesh SahooNo ratings yet

- Courage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomFrom EverandCourage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomNo ratings yet

- Busted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DFrom EverandBusted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Litigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessFrom EverandLitigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Winning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsFrom EverandWinning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsNo ratings yet

- Evil Angels: The Case of Lindy ChamberlainFrom EverandEvil Angels: The Case of Lindy ChamberlainRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- The Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadFrom EverandThe Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Greed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceFrom EverandGreed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceNo ratings yet

- Strategic Positioning: The Litigant and the Mandated ClientFrom EverandStrategic Positioning: The Litigant and the Mandated ClientRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActFrom Everand2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff 101: The Black Book of Inside Information Your Lawyer Will Want You to KnowFrom EverandPlaintiff 101: The Black Book of Inside Information Your Lawyer Will Want You to KnowNo ratings yet

- After Misogyny: How the Law Fails Women and What to Do about ItFrom EverandAfter Misogyny: How the Law Fails Women and What to Do about ItNo ratings yet

- Religious Liberty in Crisis: Exercising Your Faith in an Age of UncertaintyFrom EverandReligious Liberty in Crisis: Exercising Your Faith in an Age of UncertaintyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Diary of a DA: The True Story of the Prosecutor Who Took on the Mob, Fought Corruption, and WonFrom EverandDiary of a DA: The True Story of the Prosecutor Who Took on the Mob, Fought Corruption, and WonRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Myth of the Litigious Society: Why We Don't SueFrom EverandThe Myth of the Litigious Society: Why We Don't SueRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Scorched Worth: A True Story of Destruction, Deceit, and Government CorruptionFrom EverandScorched Worth: A True Story of Destruction, Deceit, and Government CorruptionNo ratings yet

- Lawsuits in a Market Economy: The Evolution of Civil LitigationFrom EverandLawsuits in a Market Economy: The Evolution of Civil LitigationNo ratings yet

- 2018 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActFrom Everand2018 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActNo ratings yet