Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Yalom 1967

Yalom 1967

Uploaded by

Angela EnacheOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Yalom 1967

Yalom 1967

Uploaded by

Angela EnacheCopyright:

Available Formats

Preparation of Patients for Group Therapy

A Controlled Study

Irvin D. Yolom, MD; Peter S. Houts, PhD; Gary Newell, AB; and Kenneth H. Rand, AB, Palo Alto, Calif

WILL an explanatory session preparing therapeutic framework has reoriented us to

prospective patients increase the efficacy of an appreciation of the patient's adaptive

group therapy? This article describes a con- coping mechanisms, and toward recruitment

trolled research project designed to answer of these processes in the therapeutic frame¬

this question. work.6 The utilization of patient as thera¬

The query springs from many sources. pist in staffless groups in many psychiatric

Laboratory and clinical group research has hospitals, the programming of leaderless

demonstrated the crucial importance of ear- outpatient groups,7 the instrumented Hu¬

ly meetings in shaping the future course of a man Development Institute programs for

group.1 Group norms established early in interpersonal learning (unpublished materi¬

the life of the group tend to persist, outliv- al by J. Berlin and B. Wyckoff), the use

ing even a complete turnover in the group of peers or near peers as therapists,8 and the

population.2 Approximately one third of all many responsible programs in progress for

patients beginning group therapy in a uni- training nonprofessionals in psychotherapy

versity outpatient clinic drop out unim- are all manifestations of the démystification

proved during the first dozen meetings.3 trend. Psychotherapy, these approaches may

Conversely, patients who in the first 12 argue, is a rational, teachable process the

meetings achieve high group popularity, or efficacy of which is enhanced rather than

who show high satisfaction with the group, impaired by explication.

are more apt to show clinical improvement Another source of impetus for this study

at the end of 50 meetings.4 These observa- comes from the nonclinical small group

tions suggest the rationale of therapeutic in- field. Human development laboratories or

tervention early in the life of the group. A sensitivity training groups have, for many

recent study demonstrating that a pre- years, augmented the group process with ex¬

therapy "role induction interview" could planatory reading material and periodic lec-

beneficially influence the early course and turettes designed to provide a cognitive map

outcome of individual therapy provided ad¬ for the proceedings.9 Although the compara¬

ditional impetus to this study.5 If a cogni¬ bility of these groups with therapy groups is

tive orientation to therapy can so affect a still controversial, it is undeniable that there

dyadic interactional system, then its impli¬ exists much overlap in structure and process

cations for group therapy are exciting be¬ between them.

cause of the early group culture building These converging factors, then—from

which, once set into motion, is powerful and theory, research, and clinical practice—all

relatively irrevocable. suggest the importance and timeliness of a

Recent developments in the entire field of controlled investigation into the effects on

psychotherapy also suggest that a cognitive patient behavior and attitudes of a systema¬

orientation of the prospective patient might tic explicatory session prior to the beginning

beneficially influence therapy. Clearly there of group therapy. This explicatory session

is an important trend toward demys¬ instructs patients to engage in here-and-now

tification of the psychotherapeutic process, interaction focusing on relationships among

toward a defrocking of the therapist, toward group members and, in addition, was de¬

a more collaborative venture between pa¬ signed to increase faith in group therapy

tient and therapist. An ego-based psycho-N and attractiveness of the therapy group. The

Submitted for publication March 31, 1967. experimental groups, which had an explica¬

From the Department of Psychiatry, Stanford tory session, were compared with control

University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, Calif. groups which had no such session. Three hy¬

Reprint requests to Stanford Medical Center, Palo

Alto, Calif 94304 (Dr. Yalom). potheses were studied.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

Hypothesis 1.—Patients in the experi¬ formed of the immediate availability of

mental groups were expected to have greater group therapy. Excluded from consideration

faith in group therapy than patients in con¬ flagrantly psychotic patients, addicts,

were

trol groups. alcoholics, and patients with mental retarda¬

Hypothesis 2.—Patients in the experi¬ tion or organic syndromes.

mental groups were expected to have greater The (»therapists of the six groups were 12

attraction (cohesiveness) to their groups first-year residents. During the first seven

than in control groups. months of their residency they had had an

Hypothesis 3.—Patients in the experi¬ intensive group therapy training course con¬

mental groups were expected to engage in sisting of weekly didactic sessions and clini¬

more here-and-now discussion of interper¬ cal seminars, and a 50-hour sensitivity train¬

sonal relations within the group than pa¬ ing group experience. They had observed

tients in control groups. experienced group (»therapists conduct ap¬

proximately 20 group therapy meetings

Method (with a similar patient population) and par¬

ticipated in postgroup "rehash" sessions.

Summary of Research Design.—Sixty pa¬ The general orientation of the program was

tients on the group therapy waiting list of a a dynamic, interactional one. One of the

university outpatient clinic were interviewed therapist's chief tasks was formulated as

by one of us (I. D. Y.) prior to the first meet¬ helping the group mature into the thera¬

ing with their group therapists, and were peutic agent. Emphasis was placed on the

randomly assigned to one of two conditions. importance of immediate expression of feel¬

The experimental subjects were given a sys¬ ings and here-and-now interaction, Therapy

tematic 25-minute preparatory lecture on centered on the understanding and correc¬

group therapy, whereas the control subjects,

tion of parataxic distortions among the

although seen by the same researcher for an group members and of general maladaptive

equal period of time, did not receive the interpersonal stances.

group orientation lecture. The patients then Following their sensitivity group experi¬

went into six therapy groups—three groups ence, the residents selected (»therapists.

of experimental subjects and three groups of The six (»therapist pairs were then divided,

control subjects. These groups were studied on the basis of the faculty's general assess¬

for the first 12 meetings to determine what ment of their competence, into two equal

differences, if any, resulted from our manip¬ groups of three (»therapists each. Three of

ulation. Throughout this study the group these cotherapist pairs were randomly se¬

therapists were totally unaware of the na¬ lected to lead the three groups of experimen¬

ture or design of this research. tal subjects, and the other three cotherapist

Clinical Setting.—Our sample was repre¬ pairs to lead the three control groups. It is

sentative of the population in the Stanford important to repeat that the therapists were

University outpatient clinic and has been never aware of the nature of this research.

described in detail in previous reports.3·4 It is common clinic practice for one of us

The mean age was 28, with a range from 18 (I. D. Y.) to see group patients in a pre¬

to 49. The population, largely from the mid¬ liminary screening interview. Postgroup pa¬

dle socioeconomic class, was a sophisticated, tient questionnaires and tape-recordings of

well educated one; 94% had graduated from the meetings for research purposes are also

high school and 72% had had some college part of routine clinic practice and have been

education. Fees ranged from $1 to $10 per continuously utilized in the clinic for four

session. Diagnostic classification primarily years.

indicated characterologic or neurotic disor¬ Procedure.—The 60 patients on the group

ders. Occasionally a patient was labeled waiting list were randomly divided into two

as a borderline schizophrenic or psycho¬ equal groups of experimental and control

physiological reaction. Approximately two subjects. All 60 were asked to come to the

months before the groups were scheduled to clinic to meet with the associate director of

begin, a group therapy waiting list was the clinic (I. D. Y.) for registration and for

formed. All patients applying for therapy a discussion regarding their request for

during this time were considered for group group therapy. The first patients were seen

therapy. Local referring sources were in- in small groups of three to five, but schedul-

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

ing made this design impractical people in their lives now, as well as with people

pressures

and the great majority of patients were seen they had yet to meet.

individually. The patients were advised that the way they

The experimental patients were given a could help themselves most of all was to be

25-minute group preparatory lecture. The and honest direct with their feelings in the

group at that moment, especially their feelings

major goals of this presentation were: (1) towards the other group members and the ther¬

To enhance the patient's faith in group apists.

This point was emphasized many times

therapy. (2) To enhance the attractiveness and was referred to as the "core of group thera¬

(cohesiveness) of the patient's specific py." They were told that they may, as they de¬

group. (3) To direct the patient toward con- velop trust in the group, reveal intimate aspects

frontive, here-and-now interaction in the of themselves, but that the group was not a

group. (The greatest proportion of the pre¬ forced confessional and that people had

paratory session was devoted to this goal.) differential rates of developing trust and re¬

To accomplish these goals the orientation vealing themselves. It was suggested to them

presented the patients with a rational de¬ that the group could be seen as a forum for

scription of the practice, the theoretical ba¬ risk-taking, and that as learning progressed,

new types of behavior might be tried in the

sis, and the results of group therapy. Possi¬

ble sources of stress were identified. Finally, group setting.

Certain stumbling blocks were predicted. Pa¬

patients were instructed to discuss their feel¬ tients were forewarned about a feeling of puz¬

ings about other group members. The pres¬ zlement and discouragement in the early meet¬

entation was informal and questions were

ings; it would, at times, not be apparent how

solicited and answered. A descriptive ac¬ working on group problems and intragroup re¬

count of the orientation follows. lationships could be of value in solving the

A brief explanation of the interpersonal problems which brought them to therapy. This

theory of psychiatry began with the statement puzzlement, they were told, was to be expected

that everyone seeking help in group therapy in the typical therapy process, and they were

had in common the basic problem of encounter¬ strongly urged to stay with the group and not

ing difficulty in establishing and maintaining to heed their inclinations to give up therapy.

close and gratifying relationships with others, They were told that many patients found it

although each group member manifested his painfully difficult to reveal themselves or to ex¬

problems differently. They were reminded of press directly positive or negative feelings. The

the many times in their lives that, undoubtedly, tendencies of some to withdraw

emotionally, to

they wished to clarify a relationship, to be real¬ hide their feelings, to let others express feelings

ly honest about their positive or negative feel¬ for them, or to form concealing alliances with

ings with someone and get reciprocally honest others were discussed. The therapeutic goals of

feedback from others. The general structure of group therapy were described as ambitious: we

society, however, does not often permit totally desired to change behavior and attitudes many

open communication. The therapy group, it years in the making; treatment, therefore,

was emphasized, is a special microcosm where would be gradual and many, many months in

this type of honest interpersonal exploration duration. We discussed with them the

vis-a-vis the other members is not only permit¬ velopment of feelings of frustration or annoy¬

likely de¬

ted, but encouraged. If people are conflicted in ance with the therapist, how they would in vain

their methods of relating to others, then ob¬ expect answers from him. The source of help

viously a social situation which encourages would be primarily the other patients. We

honest interpersonal explorations can provide knew, we told them, of their difficulty in ac¬

them with a clear opportunity to learn many cepting this fact, of their probably wondering

valuable things about themselves. It was em¬ "How can the blind lead the blind?"

phasized to them that working on their rela¬ Next they were told about the history and

tionships directly with other group members development of group therapy. We described,

would not be easy; in fact, it might be very for example, how group therapy passed from a

stressful; but it was of the utmost importance stage during the second world war when it was

because if one could completely understand valued because of its economic feature in allow¬

and work out one's relationships with the other ing psychiatry to reach a large number of pa¬

group members, there would be an enormous tients, to its present position in the field where

carry over. They would then find pathways to it is clearly seen as having something unique to

more rewarding relationships with significant offer and is often the treatment of choice. Re-

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

suits of psychotherapy outcome studies were groups with a total of 20 control subjects,

cited in which group therapy was shown to be and three groups with a total of 23 experi¬

as efficacious as any mode of individual thera¬ mental subjects. The (»therapists, of course,

py. An outcome project4 at Stanford conducted made the final decision as to whether an as¬

last year was described in which it was shown

that a very high proportion of group therapy

signed patient should begin therapy in his

group. Seventeen (nine experimental and

patients who remained in group therapy for a

year were significantly improved. Our remarks

eight control patients) did not begin group

in this area were focused toward instilling faith therapy: either they were not accepted by

in group therapy and dispelling the false notion the group therapists, or they themselves

of many patients that group therapy is "second elected not to begin.

class therapy," to be used when individual Each pair of (»therapists was supervised

treatment is unavailable. one hour a week by a highly experienced

Lastly, we attempted to enhance the attrac¬ clinician. Each supervisor was assigned two

tiveness of their particular group. Before the groups, an experimental and a control

interview they were asked to hand in two lists group. Everyone involved—therapists, pa¬

of traits: one characteristic of people whom tients, and supervisors—was unaware of the

they liked, and another characteristic of those nature of the research. The residents knew

whom they disliked. During the interview they that some type of research was in progress,

were told that we would place them in a group

which was maximally compatible with them,

because we collected tapes of each meeting

and that we would use their Usta in this task.

and postgroup questionnaires; but they were

This device, although a well-accepted small not aware, even a year later, that there had

group research technique, was the only part of been

experimental manipulation.

an

the group preparatory interview which was de¬ Comparison Measures.—The six groups

ceptive. were studied throughout their first 12 meet¬

The control patients were also seen by the ings. Six different measures

were selected to

same interviewer for 25 minutes; registration

compare the three experimental groups with

data and some historical material were ob¬

the three control groups.

tained. They were then given a brief "orienta¬

tion" to group therapy; however, all the points Hill Interaction Matrix.—Inasmuch as

covered were facts that they would have our major emphasis in orienting patients

learned at their first therapy meeting. For ex¬ was on how they should behave in the group

ample, we told them about the size of the sessions, our main concern was with how

group, the number of therapists, the probable they did, in fact, behave in the groups. The

age range of the group members, the length of Hill Interaction Matrix10 method of scoring

the meetings, and the fees. They were informed interaction in therapy groups was well-suited

that attendance was very important for their to measure the effects of our manipulation.

therapy and, like the experimental group, they While we cannot describe the scoring sys¬

were urged not to drop out but to make a com¬ tem in detail here, a brief description is in

mitment to attend at least a dozen meetings be¬ order to understand the results. Hill's scor¬

fore attempting to evaluate the value of the

ing method consists of a 4 X 4 matrix, which

group to them. Both the experimental and con¬ is shown in Table 1. All statements are

trol patients were informed that a group thera¬

pist would call them within two weeks. scored and placed in one of 16 cells. For

The next step was patient assignment. purposes of clarity we have used a different

The clinic psychiatric social worker was giv¬ lettering system from the one described in

the Hill manual. Hill described a fifth row,

en two patient lists, A (control) and a

(experimental), as well as a list of three Responsive, which is intended for groups of

chronic regressed patients but which is not

pairs of A group therapists and three pairs

group therapists; they were then asked applicable

of to our population.

to assign the patients to the appropriate Hill considers the speculative and con-

groups. The social worker was not aware of frontive statements (rows Y and Z) to be

the identity of the A or condition. He at¬ "work" statements because someone is tak¬

tempted to fill one A or group at a time, ing the role of a patient and actively seeking

striving for an equal male-female, single- self-understanding. He considers the asser¬

married ratio. Finally there were three tive and conventional statements (rows W

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

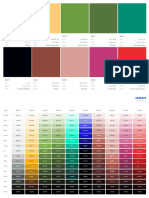

and X) to be "non-work" because the pa¬ Table 1.—Modified Hill Interaction Matrix

tient role is avoided. 3 4

12

Before analyzing the Hill ratings, the 16 Relation-

types of statements were divided into three Topic Group Personal ship

major categories: (1) directly oriented state¬ W Conventional 1W 2W 3W 4W

ments (cells 2W, 2X, 2Y, 2Z, 4W, 4X, 4Y, X Assertive IX 2X 3X 4X

3Y

4Z) ; (2) indirectly oriented statements Y Speculative

Confrontive

1Y

1Z

2Y

2Z 3Z

4Y

4Z

(cells 3X, 3Y, 3Z) ; and (3) nonoriented The columns refer to types of content:

statements (cells 1W, IX, 1Y, 1Z, 3W). 1. Topic statements are about topics of general in¬

The directly oriented category is the one terest exclusive of the group or its members.

2. Group statements deal with the group as an entity.

most relevant to our preparatory session. If 3. Personal statements are about a group member

this sessionwere effective, then we would independent of his relationships with other members of

the group.

anticipate that the three experimental 4. Relationship statements deal with relationships

between members and between a member and the

groups would score higher than the three group.

control groups in this category, which con¬ The rows refer to levels of work:

W. Conventional statements are socially appropriate

sists of group and relationship statements. for any group. They consist largely of social pleasantries

Since the preparatory session did not spe¬ and discussions of one's problems in a conventional,

socially appropriate manner without putting oneself in

cifically stress different work levels (rows), a patient role.

all levels of group and relationship state¬ X. Assertive statements are argumentative and hos¬

tile. They often involve blaming others -ather than

ments were placed in this category. oneself for problems, and so evade the patient role.

Y. Speculative statements deal with therapeutic issues

The indirectly oriented category consists in a speculative intellectual way.

of all personal statements made by a mem¬ Z. Confrontive statements confront patients or the

group with aspects of their behavior usually avoided,

ber with the exclusion of superficial, conven¬ 3nd with some documentation to allow reality testing.

tional statements; we speculated that the

experimental groups would score higher groups had been oriented when they scored

than the control groups in this category. Al¬ the interaction.

though the preparatory session did not spe¬ Interaction was scored from tape record¬

cifically orient patients to speak on personal ings of the second, fifth, and twelfth meet¬

levels, we reasoned that the decreased un¬ ings of each of the six therapy groups. The

certainty and increased trust in group thera¬ second meeting was chosen because first

py would indirectly permit them to speak meetings of therapy groups are often ritual¬

more freely about personal problems with ized introductions with little opportunity

less need to engage in superficial conven¬ for serious interaction. The twelfth meeting

tionalities. In combining assertive with spec¬ was the last one scored because we had asked

ulative and confrontive levels we differ subjects to stay through 12 meetings before

somewhat from Hill, who would call asser¬ deciding whether to remain or leave their

tive level interaction nonwork because the groups. This procedure, it was hoped, would

patient is avoiding the patient role. How¬ Table 2.—Postgroup Questionnaire

ever, we felt that assertive statements can in¬

dicate emotional involvement and are often 1. I found the meeting today to be

good bad

part of serious therapy. .

2. Compared with how much you would tell a casual

The nonoriented category consisted of all friend, how frankly did you express your feelings about

the remaining statements, mostly superficial other group members?

very frank not frank

interaction often referred to as group flight .

3. Compared with how much you would tell a casual

or resistance. If the preparatory session friend, how much of your private life did you tell the

were effective in enabling the experimental group today?

a great deal none at all

groups to engage in group work more quick¬

.

4. How would you rate your mood right now?

ly, then we would expect them to score low¬ a. angry .

not angry

tense

er in this category. b. relaxed .

c. discouraged . hopeful

Three of us were trained in scoring inter¬ d. involved with others.. .withdrawn from others

action with the Hill Interaction Matrix and 5. The group worked together today

notatali very well

had achieved an 80% agreement with Hill's

.

6. I made progress ¡n achieving my goals in therapy

criterion test prior to scoring these proto¬ today

deal

cols. The three raters did not know which none . a great

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

minimize the number of dropouts during the perimental group scores were combined for

research period. each meeting, as were the scores for the

The middle half-hour of each meeting was three control groups. The percentage of

scored. Two raters listened to each statements occurring in the three statement

recording and peached a consensus on the categories for each of the meetings are

scoring of each statement. A scorable state¬ shown in Fig 1.

ment consisted of one person's continuous The percentage of directly oriented state¬

talk within one of the Hill categories. Thus ments is higher for the experimental than

a long, uninterrupted soliloquy by one pa¬ for the control groups on all three of the

tient entirely in one category would be rated meetings, whereas the percentage of

scored only once. If he were interrupted by nonoriented statements is lower for the ex¬

someone else, even if the interrupter were perimental groups on all three meetings.

also speaking in the same category, the in¬ The indirectly oriented statements show a

terruption itself would be scored, as would more complex pattern, with the oriented

the resumption after it. If talk shifted to an¬ groups higher on meetings two and five, but

other category and then returned, the other lower on meeting 12.

category would be scored, as would resump¬ Since the three-statement categories form

tion of the first category. Since most state¬ a rank order from oriented to indirectly ori¬

ments were terminated by another person's ented to nonoriented, a Mann-Whitney two-

speaking rather than the same speaker shift¬ sample rank test was used to test the

ing to another category, the total number of differences between the experimental and

statements scored in a half-hour period is a control groups for weeks two and twelve.

rough index of the amount of interaction The differences on week five were in the ex¬

during the period. pected direction, but did not reach statisti¬

Each rater scored an equal number of ori¬ cal significance. The lack of significant dif¬

ented and nonoriented groups for each ferences on week five raised the possibility

meeting studied. that the effect of the orientation was curvi¬

Postgroup Questionnaires.—At the end of linear over time: high at the beginning and

every therapy meeting the patients filled out later in the group, but overshadowed by oth¬

a questionnaire consisting of nine items, er factors around the fifth meeting. It is also

each answered on a 7-point scale; this ques¬ possible that the lack of significant results

tionnaire is reproduced in Table 2. was due to sampling error.

Cohesiveness Questionnaire.—A ten-ques¬ In order to investigate the alternatives

tion cohesiveness questionnaire, described further, we scored the sixth meetings of all

elsewhere,11 was filled out by the patients groups. (Raters were, again, not aware of

at the end of the fourth, eighth, and twelfth which were the experimental and which the

meetings. control groups.) The results are shown in

Faith in Group Therapy Questionnaire.—- Fig 2 and Table 4. In meeting six the experi¬

Before therapy (immediately after the mental groups had more directly and indi¬

group preparatory or control interview), rectly oriented statements and fewer non¬

and once again after the twelfth meeting, oriented statements than did the control

the patients answered two questions: (1) groups. These differences are in the same

What percent of people who start group direction as in meeting five and are now sta¬

therapy do you think are helped by group tistically significant using the Mann-Whit¬

therapy? (2) How long do you think it takes ney rank test. This indicates that the lack of

the average person to get definite benefit significant differences between experimental

from group therapy? and control groups in the fifth meeting were

Attendance and dropout records were not indicative of a curvilinear effect of the

kept. preparatory session over time and may have

Clinical data were available on each been due to sampling error.

group from tapes and from a summary of In order to test in more detail how the

each meeting dictated by the therapists. three statement categories differed between

Results the oriented and nonoriented groups, the

Hill Interaction Matrix.—The three ex- 2X3 contingency tables in Tables 3 and 4

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

were each partitioned into three 2 2 2 ta¬ Week 1

bles. The results, shown in Table 5, tell us Il Experimental qroups

60

more about the differences over time be¬ 1 I Control groups

tween the oriented and nonoriented groups.

All three 2 are significant for week two, 40

indicating that the experimental groups ex¬

ceed the control groups to a greater degree

20

on oriented than on nonoriented statements

and have a greater proportion of both direct¬

ly and indirectly oriented statements than of § O

nonoriented statements. This is exactly Week 5

what we would have expected from our ma¬ 60

nipulation: its strongest effects were shown

-

on directly oriented, and the next strongest

on indirectly oriented statements. £40

O

+-

Week five has no statistically significant

differences among the three statement cate¬ O 20

gories, whereas week six again shows a sig¬ c

nificantly greater proportion of both directly

and indirectly oriented statements than of g 0

Week \Z

nonoriented statements for the experimental 60

groups. However, counter to our expecta¬

tions that the largest difference between ex¬

perimental and control groups would be 40

with oriented statements, the experimental

groups exceeded the control groups to a 20

greater degree on indirectly oriented than on

oriented statements.

Week twelve is similar to week six, except Indirectly Non¬

Oriented

that this time the difference in proportion of statements oriented oriented

statements statements

indirect vs nonoriented statements is not

significant for the two types of groups. Fig 1.—Percent of oriented, indirectly oriented, and

nonoriented statements made in weeks two, five, and

The most consistent finding over the twelve.

weeks is that, for the oriented groups, the

proportion of directly oriented statements is

significantly greater than the proportion of we would expect five of them to exceed this

nonoriented statements. The results with probability level. We therefore must con¬

the indirectly oriented statements are more clude that these two differences may have

equivocal and, since they do not follow a been due to chance.

consistent pattern, are difficult to interpret.Cohesiveness Questionnaire.—Cohesive¬

Postgroup Questionnaires.—The experi¬ ness scores of the experimental and control

mental and control groups were compared groups were compared for the fourth, eighth,

on each of the nine postgroup questionnaire and twelfth meetings. No statistically sig¬

items for each of the first 12 meetings. Out nificant differences were found between the

of these 108 comparisons, two had probabili¬ two groups on any of these meetings.

ty levels of less than 0.05: at meeting ten, Faith in Group Therapy.—Immediately

members of oriented groups rated their mood following the orientation session, (prior to

as more tense than did members of non¬ therapy) and again at the twelfth meeting,

oriented groups, and at meeting five, mem¬ all patients were asked to estimate the per¬

bers of oriented groups rated themselves as centage of people helped by group therapy

making more progress toward their goals and the amount of time required for benefit.

than did members of nonoriented groups. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used as a

However, if this number of comparisons test of statistical significance. There were no

were to be made from a random population, statistically significant differences between

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

Table 3.—Statements in the Three Categories dropouts often presents a formidable ob¬

tor Experimental and Control Groups on stacle in group therapy research. The tech¬

Weeks 2, 5, and 12

nique of urging patients to remain in therapy

Statements for a minimum set period may prove useful

Non¬

to other workers.

Groups Oriented Indirect oriented Week

Comment

Experimental 67 104 124 2*

Control 17 53 118

Experimental 37 84 143

5

Hypothesis 1 (greater faith in group

Control 33 85

55

173

41

therapy among experimental subjects) re¬

Experimental 118 12* ceived some support from our findings.

Control 62 96 109

*

P<0.05, Mann-Whitney two-sample rank test cor¬ Hypothesis 2 (greater cohesiveness

rected for ties. among the experimental subjects) was not

the experimental and control groups prior to

supported by our findings.

Hypothesis 3 (greater here-and-now inter¬

therapy. At the twelfth meeting, however, personal interaction among experimental

the experimental patients estimated signifi¬

subjects) was strongly supported by our

cantly shorter times required for benefit findings.

from group therapy (P < 0.05). They also To interpret these findings let us review

estimated that a larger percentage of pa¬ those aspects of the preparatory session rele¬

tients was helped by group therapy than did

vant to each hypothesis.

the control group, but this difference did not

reach statistical significance (P < 0.10). Hypothesis 1.—In the preparatory session

we attempted to enhance the patients' faith

Attendance and Dropout Records.—The in group therapy by citing encouraging out¬

experimental and control groups did not come studies, by describing the unique fea¬

differ significantly in the number of drop¬

tures of group therapy, and, no doubt, by

outs. At the end of ten months, ten experi¬

mental and ten control patients had dropped transmitting the interviewer's enthusiasm

for the modality. There is considerable re¬

out from group therapy. The mean stay of search evidence that positive structuring of

the experimental patient was longer (18.2 the patients' initial expectations beneficially

meetings) than for the controls (11.7 meet¬ influences the course and outcome of indi¬

ings). This difference was not, however, sig¬ vidual therapy,12·13 and our results sug¬

nificant. The early attendance pattern is in gest that a similar process may occur in

itself quite interesting. All 43 patients were

strongly urged to remain in therapy for at

least 12 weeks, and only 14% of the group Table 4.—Statements in the Three Categories

for Experimental and Control Groups on Week 6*

members dropped out during the first 12

meetings—less than half the number of Statements

dropouts observed in the same population in Groups Oriented Indirect Nonoriented

previous studies.3 The high rate of early Experimental 139 153 92

Control 83 55 123

c *

P<0.05 Mann-Whitney two-sample rank test cor¬

Week 6 rected for ties.

§60

+-

O

I 1

Experimental groups

I I Control groups

. - Table 5.—x~ Values tor Partitioned Tables

(

Comparing Experimental and Control Groups

40

+- Week

o

+-

Statements 2 5 6 12

%20 Oriented vs indirect 4.85* 0.20 5.91* 27.93:

Oriented vs non¬

0L oriented 20.91t 1.33 17.22; 47.88t

Oriented Indirectly Non¬ Indirect vs non¬

statements oriented oriented oriented 8.75f 0.88 41.42 í 2.86

statements statements

* P<0.05.

Fig 2.—Percent of oriented, indirectly oriented, and t P<0.01.

nonoriented statements made in week six. î P<0.001.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

group therapy. We tested for this effect by crease anxiety. In addition, we attempted to

asking the patients (pretherapy, and again clarify the goals of therapy.

at the twelfth meeting) to estimate the per¬ One important source of perplexity and

centage of patients helped by group therapy discouragement for patients in the initial

and the duration of time required. At the stages of group therapy is a perceived goal

twelfth meeting the experimental groups incompatibility. They will often be unable

tended to be more optimistic than the con¬ to discern the connection between group

trol groups. goals (group integrity, construction of an

Hypothesis 2.—In the preparatory inter¬ atmosphere of trust, and an interactional

view we also attempted to increase the mem¬ confrontive focus) and the individual goals

bers' satisfaction with their groups by telling of the patient (relief of suffering). Part of

them that, on the basis of their question¬ the task of the preparatory interview was to

naire data, they would be placed in a maxi¬ disconfirm the apparent incompatibility,

mally compatible group. However, the cohe¬ and to clarify how these goals are, in fact,

siveness questionnaire scores (obtained at confluent. The preparatory interview, fur¬

fourth, eighth, and twelfth meetings) of the thermore, attempted to clarify expected role

experimental groups were not significantly behavior. The patients were presented with

higher than those of the control groups. This unambiguous guidelines for their behavior

procedure, one which has traditionally been in the group. Types of efficacious and self-

successful in laboratory research, may have defeating behavior were concretely described,

failed in this research for several reasons. and the rationale behind our value judge¬

First, the emphasis on cohesiveness in the ments was explained. The ambiguity sur¬

preparatory interview was very weak, con¬ rounding the role of the therapist was also

sisting of only a single sentence. Secondly, lessened by outlining his goals and purpose

the cohesiveness questionnaire, adapted in the group.

from laboratory small-group research, may The importance of clarity of goals and

have overemphasized being comfortable in role expectations in effective group function¬

the group, and the more interactive task-ori¬ ing has been demonstrated by an abundance

ented experimental groups may well have of small group research, recently re¬

been less comfortable for the members, viewed.15 In laboratory groups, increased

though more cohesive or binding. It is inter¬ clarity of goals and increased explication of

esting to note that two of the control groups the methods of goal attainment result in

fragmented shortly after the end of the for¬ greater member attraction to the group,

mal study, losing three members each be¬ increased sympathy for group emotions,

tween the 13th and 16th meetings. The im¬ decreased intermember hostility, increased

pact and stress of the early meetings of the intermember influencability, increased moti¬

experimental groups may well have neutral¬ vation, increased member security, in¬

ized the weak initial favorable expectation creased efficiency, and decreased member

we implanted. In fact, Goldstein14 cites evi¬ frustration.1619 Ambiguous group-member

dence that individuals who are exposed to role expectations reduce group satisfaction

more stress than anticipated may react with and group productivity and increase mem¬

hostility at the disconfirmation of their ex¬ ber defensiveness. Many psychotherapy and

pectations. group dynamic studies have demonstrated

Hypothesis 3.—The third goal and major that the more discrepant the member's ex¬

emphasis of the preparatory interview was pectancies of the group leader's role, the

to increase the development of interpersonal "less the attraction to the group, the less the

interaction in the group. Our method was to satisfaction of group members, and the more

provide a cognitive structure for the patient. the strain or negative affect between leader

We clarified the rationale of group therapy and led or therapist and patient."20

by briefly explaining the interpersonal theo¬ The results of our study indicate that pa¬

ry of psychiatry and the advantages of an tients systematically prepared for interac¬

interactional focus in the group. Through tional group therapy, will engage themselves

this explanation, and through predictions of more quickly in the therapeutic task than

anticipated obstacles, we attempted to de- patients not so prepared. Considerable evi-

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

dence, cited above, suggests that increased guity, absence of cognitive anchoring, and

clarity of goals and paths to attain these frustration of conscious and unconscious

goals, as well as increased clarity of role ex¬ wishes all facilitate a regressive reaction to

pectations, result in conditions more condu¬ the therapist and help create an atmosphere

cive to effective therapy. Why, then, are pa¬ favorable for the development of transfer¬

tients not routinely prepared for group ence toward the therapist and parataxic dis¬

therapy in a systematic manner? In fact, tortions toward other group members. These

all group therapists do attempt to clarify therapists wish to encourage regressive phe¬

the therapeutic process and expected role be¬ nomena and the emergence of unconscious

havior, and the difference between therapists impulses so they may be identified and

or between therapeutic schools is largely worked through in therapy.29

a difference in timing and style of prepara¬ Other therapists, who deemphasize the

tion. Some group therapists initially pre¬ centrality of the patient-therapist relation¬

pare the new patient by providing him with ship in group therapy and look to total

written material about group therapy,21 or group forces as the therapeutic agent, also

by having him hear a tape of a model group argue against the initial clarification of

therapy work meeting (as noted by B. Ber- group goals and process. If, as Bion states,30

zon in an oral communication, May 1965), the chief task of the group is to analyze its

or by having him attend a trial meeting,22 own tensions, then the anxiety stemming

or by a long series of individual intro¬ from initial uncertainty surrounding the ex¬

ductory lectures or an instrumented pro¬ pected group process forms the initial group

gram of therapy and insight aids.23·24 task. Others31 point out that the initial anx¬

However, even the therapists who deliber¬ iety encourages the group toward an early

ately abrogate initial preparation and orien¬ problem-solving culture and eventual group

tation of the patient nevertheless have in autonomy; one cannot, it is argued, establish

mind goals and preferred modes of group group solutions by edict. Slavson insists that

procedure which eventually are transmitted initial anxiety is a desirable feature, since it

to the patient. By subtle, or even subliminal, delays the development of group cohesive¬

verbal and nonverbal reinforcement, even ness.32 The group thus does not develop a

the most nondirective therapist structures degree of comfort incompatible with thera¬

his group so that inevitably it adopts his val¬ peutic work.

ue system of high and low priority content An authoritative discussion of these issues

and process.25·26 This was illustrated by is difficult because of the dearth of relevant

the fact that even the control groups consist¬ sound research. The identification and the

ently increased in the percentage of oriented rank ordering of the curative factors in

statements throughout the 12 meetings. (Fig

group therapy is entirely problematic. Some

1 and 2).

pertinent research studies4·33·84 suggest that

If we accept the research evidence that the important curative forces are total

the group therapist's goals and preferred

group and interactive in nature; for exam¬

procedural paths to goal attainment are ulti¬ ple, group support, group cohesiveness, and

mately transmitted to the group, why, then, popularity in the group. Nevertheless, there

is an initial systematic preparation of pa¬

are many different group therapies, and it is

tients uncommon in group therapy prac¬

tice? possible that the relative importance of the

curative forces varies depending on the ther¬

Some therapists hold that ambiguity of

both patient and therapist role expectation apist's goals and techniques. Thus there

is a desirable condition of the early phases may exist well thought out and appropriate

reasons for deliberate perpetuation of initial

of therapy.27·28 If one accepts the premise

that the development and eventual resolu¬ unclarity. However, if interpersonal interac¬

tion of patient-therapist transference distor¬ tion is considered a desired condition in

tions is a key curative factor in therapy, group therapy, and we contend that it is in

then it follows that one should seek, during the great majority of present-day group

the early stages of therapy, to enhance the therapy, then our research demonstrates

development of transference. Enigma, ambi- that a systematic preparatory interview will

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

facilitate the appearance of interaction in ment for our patients. For learning to occur,

therapy groups. and for positive reinforcement of adaptive

A systematic preparation for group thera¬ interpersonal behavior to transpire, the

py by no means implies a structuring of the patient must feel that he is effectively in¬

group experience. We do not espouse didac¬ vestigating and producing a purposeful, ap¬

tic or directive group therapy, but, on the propriate effect on his environment. If, as

contrary, suggest a technique which will en¬ research evidence holds, anxiety is the enemy

hance the formation of a freely interacting of environmental exploration,37 then a reduc¬

autonomous group. By averting lengthy rit¬ tion of the extrinsic anxiety of uncertainty

ualistic behavior in the initial sessions, and should enhance the formation of an atmos¬

by diminishing initial anxiety stemming phere conducive to interpersonal explora¬

from unclarity, the group is enabled to tion. If patients are unclear about the long-

plunge into work more quickly. In our view, range goals of the group and the stepping

anxiety caused by deliberate unclarity is not stones to those goals, then the possibility

necessary to prevent the groups from becom¬ exists that constructive behavior will not

ing too socially comfortable. Our patients be recognized as such by the patient. Poten¬

are conflicted in their interpersonal relation¬ tially adaptive exploration may not be grati¬

ships and any groups—-for example our fying or reinforcing for the patient who sus¬

three experimental groups which have an pects that this behavior is irrelevant, or even

increased rate of interpersonal interaction— counter, to therapeutic objectives.

will continually present challenging and In conclusion, there is considerable evi¬

anxiety-fraught interpersonal confronta¬ dence from a number of sources that exces¬

tions. Therapy groups which are too com¬ sive initial anxiety, frustration, and unclari¬

fortable are groups which engage in flight ty may inhibit learning and be disconsonant

from the task of direct interpersonal con¬ with successful psychotherapy. In interac¬

frontation. tional group therapy, in which the thera¬

We would suggest that anxiety stemming peutic process is considered to be mediated

from unclarity of the group task, process, through free interpersonal interaction and

and role expectations in the early meetings the therapeutic relationship is conceptual¬

of the therapy group may, in fact, be a de¬ ized as a therapeutic alliance, we demon¬

terrent to effective therapy. Considerable strated the feasibility and efficacy of a sys¬

evidence exists that, although anxiety with tematic preparation for therapy. Through a

accompanying hypervigilance may be adap¬ pretherapy explication of the group process

tive, excessive degrees of anxiety will ob¬ and expected role behavior the therapy

struct coping with stress.35·36 In his review group is more quickly able to engage in the

of evidence supporting the concept of an ex¬ therapeutic task.

ploratory drive, White37 notes that anxiety Summary

and fear retard learning and result in de¬ In controlled investigation the effects of

a

creased exploratory behavior to an extent a pretherapy preparatory session on the ear¬

correlated with the intensity of the fear. It ly course of group therapy are studied. The

has been postulated that man has a primary findings indicate that the preparatory session

drive to explore and master his environ¬ increases the development of interpersonal

ment, and that there is an intrinsic pleasure interaction, ie, the discussion of intermember

and positive reinforcing value in the investi¬ relationships in the group. In addition, there

gation of environment, the experiencing of was some evidence that patients' faith in

competence, and the production of an effect group therapy was strengthened by the pre¬

on the environment.38 The concept that paratory session. There was no effect of the

learning is facilitated by frustration has experimental procedure on the patients' at¬

been challenged by many psychotherapists traction to their particular groups.

who conceptualize the patient-doctor rela¬ Implications of these findings for the

tionship as a therapeutic alliance. Kardi- theory and practice of group therapy were

ner39 states that it is the successful and discussed. A preparatory interview clarify¬

gratifying experiences, not the frustrations, ing group process and role expectations can

that will lead to integration. enhance the efficacy of interactional group

The early group therapy experience is a therapy by hastening the appearance of

strange, usually threatening social environ- effective levels of group communication.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

This research was partially financed by a Stan¬ 18. Cohen, A.R.; Stotland, E.; and Wolfe, D.M.:

ford University general research support grant, and An Experimental Investigation of Need for Cogni-

by NIMH grant No. MH 8304. tion, J Abnorm Soc Psychol 51:291-294, 1955.

William F. Hill, PhD, and Donald Staight, MSW, 19. Cohen, A.R.: "Situational Structure, Self-

assisted in this research.

Esteem and Threat-Oriented Reactions to Power,"

in Cartwright, D. (ed) : Studies in Social Power, Ann

References Arbor, Mich: Research Center for Group Dynamics,

1959, pp 35-52.

1. Bales, R.F.: "The Equilibrium Problem in 20. Goldstein, A.P., et al: Psychotherapy and the

Small Groups," in Parsons, T.; Bales, R.F.; and Psychology of Behavior Change, New York: John

Shils, E. (eds): Working Papers in the Theory of Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1966, p 405.

Action, Glencoe, Ill: Free Press, 1953. 21. Martin, H., and Shewmaker, K.: Written In-

2. Jacobs, R.C., and Campbell, D.T.: The Perpet- structions in Group Therapy, Group Psychother

uation of an Arbitrary Tradition Through Several 15:24, 1962.

Generations of a Laboratory Microculture, J Ab- 22. Bach, G.R.: Intensive Group Psychotherapy,

norm Soc Psychol 62:649-658, 1961. New York: Ronald Press, 1954.

3. Yalom, I.D.: A Study of Group Therapy Drop- 23. Malamud, D.I., and Machover, S.: Toward

outs, Arch Gen Psychiat 14:393-414, 1966. Self-Understanding: Group Techniques in Self Con-

4. Yalom, I.D., et al: Prediction of Success in frontation, Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas Pub-

Group Therapy, Arch Gen Psychiat 17:159-168, 1967. lishers, 1965.

5. Hoehn-Saric, R., et al: Systematic Preparation 24. Bettis, M.D.; Malamud, D.I.; and Malamud,

of Patients for Psychotherapy, J Psychiat Res R.F.: Deepening a Group's Insight Into Human Re-

2:267-281, 1964. lations, J Clin Psychol 5:114-122, 1949.

6. Bandler, B.: Health Oriented Psychotherapy, 25. Murray, E.J.: A Content Analysis for Study

Psychosom Med 21:176-181, 1959. in Psychotherapy, Psychol Monogr 70 No. 13, 1956.

7. Berzon, B.: The Self Directed Therapeutic 26. Goldstein, A.P., et al: Psychotherapy and the

Group, Int J Group Psychother 14:366-369, 1964. Psychology of Behavior Change, New York: John

8. Goodman, G.: "Companionship as Therapy: Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1966, pp 422-423.

The Use of Non-Professional Talent," in Hart, J.T., 27. Horwitz, L.: Transference in Training Groups

and Tomlinson, T.M. (eds): New Directions in and Therapy Groups, Int J Group Psychother

Client-Centered Psychotherapy, New York: Hough- 14:202-213, 1964.

ton-Mifflin Co., to be published. 28. Wolf, A.: "The Psychoanalysis of Groups," in

9. Bradford, L.P.; Gibb, J.R.; and Benne, K.D.: Rosenbaum, M., and Berger, M. (eds): Group Psy-

T-Group Theory and Laboratory Method, New chotherapy and Group Function, New York: Basic

York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1964. Books, Inc., 1963, pp 273-328.

10. Hill, W.F.: HIM: Hill Interaction Matrix, Los 29. Schiedlinger, S.: The Concept of Repression in

Angeles: Youth Study Center, University of South- Group Psychotherapy, read before American Group

ern California, 1965. Psychotherapy 24th annual conference, New York,

11. Yalom, I.D., and Rank, K.: Compatibility and January, 1967.

Cohesiveness in Therapy Groups, Arch Gen Psy- 30. Bion, W.R.: Experiences in Groups, New

chiat 15:267-276, 1966. York: Basic Books, Inc., 1959.

12. Goldstein, A.D., and Shipmen, W.G.: Patient 31. Whitaker, P.S., and Lieberman, M.A.: Pscyho-

Expectancies, Symptom Reduction and Aspects of therapy Through the Group Process, New York:

the Initial Psychotherapeutic Interview, J Clin Psy-

Atherton Press, 1964, p 208.

chol 17:129-133, 1961. 32. Slavson, S.: A Textbook in Analytic Group

13. Frank, J.: The Dynamics of the Psychothera-

peutic Relationship, Psychiatry 22:17-39, 1959. Psychotherapy, New York: International Universi-

ties Press, 1964.

14. Goldstein, A.P.; Heller, K.; and Secrest, L.B.:

33. Dickoff, H., and Lakin, M.: Patients' Views of

Psychotherapy and the Psychology of Behavior

Change, New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., Group Psychotherapy: Retrospections and Interpre-

1966, p 405. tations, Int J Group Psychother 13:61-73, 1963.

15. Goldstein, A.P.; Heller, K.: and Secrest, L.B.: 34. Kapp, F.T., et al: Group Participation and

Psychotherapy and the Psychology of Behavior Self-Perceived Personality Change, J Nerv Ment

Change, New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., Dis 139:255-265, 1964.

1966, pp 376-377. 35. Janis, I.L.: Psychological Stress: Psychoana-

16. Rauer, B.H., and Reitsema, J.: The Effects of lytic and Behavioral Studies of Surgical Patients,

Varied Clarity of Group Goal and Group Path Upon New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1958.

the Individual and His Relation to His Group, Hu- 36. Basowitz, H., et al: Anxiety and Stress, New

man Relations 10:29-45, 1957. York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., 1955.

17. Wolfe, D.M.; Snock, J.D.; and Rosenthal, 37. White, R.W.: Motivation Reconsidered: The

R.A.: Report to Company Participants at 1960 Uni- Concept of Competence, Psychol Rev 66:297-333,

versity of Michigan Research Project, Ann Arbor, 1959.

Mich: Institute of Social Research, 1961, in Gold- 38. Hendrick, I.: Instinct and the Ego During In-

stein et al: Psychotherapy and the Psychology of fancy, Psychoanal Quart 11:33-58, 1942.

Behavior Change, New York: John Wiley and Sons, 39. Kardiner, A., and Spiegel, H.: War Stress and

Inc., 1966, p 391. Neurotic Illness, New York: Hoeben Co., 1947.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Michigan User on 06/14/2015

You might also like

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Secret Behind The SecretDocument4 pagesSecret Behind The Secret9continentsNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CV For Project Manager - EngineerDocument4 pagesCV For Project Manager - EngineerShaikh Ibrahim0% (1)

- Sop On Maintenance of Air Handling Unit - Pharmaceutical GuidanceDocument3 pagesSop On Maintenance of Air Handling Unit - Pharmaceutical Guidanceruhy690100% (1)

- The Development of Self-Control of Emotion PDFDocument21 pagesThe Development of Self-Control of Emotion PDFAcelaFloyretteBorregoFabelaNo ratings yet

- MCT385 PDFDocument21 pagesMCT385 PDFOleksandr YakubetsNo ratings yet

- Syllabus: Prefix & Code HRMT 622 3 Credits Course Name Talent Management Term / Year Winter 2022Document8 pagesSyllabus: Prefix & Code HRMT 622 3 Credits Course Name Talent Management Term / Year Winter 2022CL-A-11 KUNAL BHOSALENo ratings yet

- Relatii InterpersonaleDocument12 pagesRelatii InterpersonaleAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- A PRISMA Systematic Review of Adolescent Gender Dysphoria Literature: 1) EpidemiologyDocument38 pagesA PRISMA Systematic Review of Adolescent Gender Dysphoria Literature: 1) EpidemiologyAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia: Epidemiology, Causes, Neurobiology, Pathophysiology, and TreatmentDocument37 pagesSchizophrenia: Epidemiology, Causes, Neurobiology, Pathophysiology, and TreatmentAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Insomnia 1Document38 pagesInsomnia 1Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Conceptul Actual de Psihoză: RezumatDocument8 pagesConceptul Actual de Psihoză: RezumatAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Exploration and Support in Psychotherapeutic Environments For Psychotic PatientsDocument11 pagesExploration and Support in Psychotherapeutic Environments For Psychotic PatientsAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Digital Technologies For Schizophrenia Management: A Descriptive ReviewDocument22 pagesDigital Technologies For Schizophrenia Management: A Descriptive ReviewAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Lee 2021Document11 pagesLee 2021Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Amintirile Nasterii, Trauma Nasterii Si AnxietateaDocument12 pagesAmintirile Nasterii, Trauma Nasterii Si AnxietateaAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Barriers and Facilitators To User Engagement With Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic ReviewDocument30 pagesBarriers and Facilitators To User Engagement With Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic ReviewAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Factors in Group Process: Cultural Dynamics in Multi-Ethnic Therapy GroupsDocument7 pagesEthnic Factors in Group Process: Cultural Dynamics in Multi-Ethnic Therapy GroupsAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: Wai-Tong Chien, Ian NormanDocument20 pagesInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Wai-Tong Chien, Ian NormanAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- The Cardiff Anomalous Perceptions Scale (CAPS) : A New Validated Measure of Anomalous Perceptual ExperienceDocument12 pagesThe Cardiff Anomalous Perceptions Scale (CAPS) : A New Validated Measure of Anomalous Perceptual ExperienceAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Psychotic Depressive Disorder: A Separate Entity?Document7 pagesPsychotic Depressive Disorder: A Separate Entity?Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Issue On Pre-Therapy: Person-Centered & Experiential PsychotherapiesDocument6 pagesIntroduction To The Special Issue On Pre-Therapy: Person-Centered & Experiential PsychotherapiesAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Previous Psychotic Mood Episodes On Cognitive Impairment in Euthymic Bipolar PatientsDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Previous Psychotic Mood Episodes On Cognitive Impairment in Euthymic Bipolar PatientsAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Narcism Ronningstam1996Document15 pagesNarcism Ronningstam1996Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Tonepad Pedal RATDocument0 pagesTonepad Pedal RATJose David DíazNo ratings yet

- #6 Clinical - Examination 251-300Document50 pages#6 Clinical - Examination 251-300z zzNo ratings yet

- Color 1 Color 2 Color 3 Color 4 Color 5: RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk NameDocument4 pagesColor 1 Color 2 Color 3 Color 4 Color 5: RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk NameValentina TorresNo ratings yet

- Charge Coupled Device (CCD) : Presented byDocument18 pagesCharge Coupled Device (CCD) : Presented byBE CAREFULNo ratings yet

- IMO Shortlist 2010Document72 pagesIMO Shortlist 2010Florina TomaNo ratings yet

- Manual Call Points: GeneralDocument2 pagesManual Call Points: GeneralAnugerahmaulidinNo ratings yet

- LampiranDocument26 pagesLampiranSekar BeningNo ratings yet

- Crafting The Brand Positioning: Marketing Management, 13 EdDocument21 pagesCrafting The Brand Positioning: Marketing Management, 13 Edannisa maulidinaNo ratings yet

- New ... Timetable HND From 05-12 To 11-12-2022x01 JanvierDocument2 pagesNew ... Timetable HND From 05-12 To 11-12-2022x01 JanvierAudrey KenfacNo ratings yet

- Neil Armstrong BiographyDocument4 pagesNeil Armstrong Biographyapi-232002863No ratings yet

- LP JusticeFairness CC 002Document8 pagesLP JusticeFairness CC 002jijijijiNo ratings yet

- Blow Off Valves DescriptionDocument12 pagesBlow Off Valves DescriptionParmeshwar Nath TripathiNo ratings yet

- Overrunning Alternator Pulleys Oap 1Document1 pageOverrunning Alternator Pulleys Oap 1venothNo ratings yet

- Women and The Family: Essay QuestionsDocument15 pagesWomen and The Family: Essay QuestionsNataliaNo ratings yet

- Factsheet 2022Document1 pageFactsheet 2022Kagiso Arthur JonahNo ratings yet

- List of Staff - As On 25052021Document12 pagesList of Staff - As On 25052021Vismaya VineethNo ratings yet

- Honey Encryption New Report - 1Document5 pagesHoney Encryption New Report - 1Cent SecurityNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Arranged MarriagesDocument5 pagesThesis Statement Arranged Marriageskimberlypattersoncoloradosprings100% (2)

- For Moment of Inertia For PSC GirderDocument6 pagesFor Moment of Inertia For PSC GirderAshutosh GuptaNo ratings yet

- WHLP Q2 W7Document7 pagesWHLP Q2 W7Sharlyn JunioNo ratings yet

- VW - tb.17!06!01 Engine Oils THat Meet VW Standards VW 502 00 and VW 505 01Document8 pagesVW - tb.17!06!01 Engine Oils THat Meet VW Standards VW 502 00 and VW 505 01SlobodanNo ratings yet

- w505 NX Nj-Series Cpu Unit Built-In Ethercat Port Users Manual en PDFDocument288 pagesw505 NX Nj-Series Cpu Unit Built-In Ethercat Port Users Manual en PDFfaspNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Dairy Cow Third Edition John Webster All ChapterDocument77 pagesUnderstanding The Dairy Cow Third Edition John Webster All Chaptereric.ward851100% (8)

- LEO Small-Satellite Constellations For 5G and Beyond-5G CommunicationsDocument10 pagesLEO Small-Satellite Constellations For 5G and Beyond-5G CommunicationsZakiy BurhanNo ratings yet