Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bartlett 2019 Tooth Wear and Aging

Bartlett 2019 Tooth Wear and Aging

Uploaded by

Kenneth YungCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bartlett 2019 Tooth Wear and Aging

Bartlett 2019 Tooth Wear and Aging

Uploaded by

Kenneth YungCopyright:

Available Formats

Australian Dental Journal

The official journal of the Australian Dental Association

Australian Dental Journal 2019; 64:(1 Suppl): S59–S62

doi: 10.1111/adj.12681

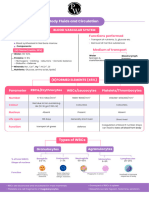

Tooth wear and aging

D Bartlett, S O’Toole

Department of prosthodontics, King’s College London Faculty for Dental, Oral and Craniofacial Sciences, London Bridge, UK.

ABSTRACT

Background: In an ageing population, tooth wear is likely to increase. It is increasing in prevalence in the younger popu-

lation and a greater number of patients are retaining their teeth into old age.

Methods: This paper is a narrative review of the clinical presentation, the epidemiology and the restorative intervention

for erosive tooth wear. The dilemmas in managing this common condition with the aging dentition in mind are

described. The paper discusses evidence-based prevention methods and highlights how preventive intervention may be

preferable over extensive restorative care and high maintenance needs. Patient wishes, expectations and commitment to

treatment and maintenance require consideration during clinical decision making.

Conclusion: Successful management of erosive tooth wear in an ageing population depends on effective diagnosis, pre-

ventive intervention and holistic advice regarding restorative intervention.

might be acceptable, whereas similar levels seen in a

INTRODUCTION

much younger person may justify care. These decisions

Tooth wear is a common condition which increases in are themselves subjective and influenced by the patient.

severity with age. For many, the gradual change in An older actor or television personality may demand

appearance and shape does not necessitate the need for the same level of appearance as a younger person, so

restorative intervention, but for some the rate of wear each situation needs a careful approach.

or severity becomes so pronounced that care should be

considered. This can take the form of prevention and

EPIDEMIOLOGY

monitoring, or restorations with composites or crowns.

The terminology used to describe the wear of teeth Recent evidence suggests that erosive tooth wear or

has evolved. For some, particularly in Europe, the tooth wear is common with up to 29% of young

focus is on erosion and that has meant an acknowl- adults showing some signs of the condition.1 It is

edgement that acids are crucially important to the likely that the deciduous dentition shows even higher

process. In other cultures, the focus has remained levels and almost reaches normal levels.2 But it is the

more broadly on tooth wear; erosion, attrition and older age groups that show higher levels of wear as

abrasion. To alleviate and find common ground, the the ravages of time and use impact on the shape of

term erosive tooth wear has been proposed to capture teeth. There is evidence that tooth wear is correlated

the meaning that erosion often is involved, even if it to aging3 and this matches clinical experience.

is not dominant. Acknowledging that, attrition and Scoring the level of tooth wear or using indices such

abrasion remain causative factors, and they can exac- as the BEWE4 are essential tools to allow dentists to

erbate the condition, they are rarely the sole agent. record the severity of wear. When used in research for

Some experts use the term pathological levels of wear epidemiology the reproducibility of the scoring can be

to describe the situation when restorative intervention challenging. Some screening tools have been criticised

could be justified. The term yields support from many, for being too detailed, meaning it is difficult for two dif-

but it is a subjective opinion, mainly held by dentists. ferent dentists to agree on a score. Conversely, some

The patient is either concerned about their appearance screening tools have been criticised for not being

or not. The appropriateness of the term “pathological detailed enough making it difficult to monitor small

tooth wear” is complex. It can be useful in trying to changes in tooth wear progression. However, in an age

explain to patients that their tooth wear experience is where clinical record keeping is so important, using a

not severe and might not demand intervention. In prin- scoring system to screen and report on tooth wear is

ciple, the level of wear seen in an older aged person essential. The BEWE fulfils this need and as the name

© 2019 Australian Dental Association S59

D Bartlett and S O’Toole

implies it allows assessment of erosive tooth wear and

for reasons given above it has international acceptance.

CLASSIFYING WEAR IN AN AGING POPULATION

In an ageing population where the overall levels of wear

are high, there is conflict over what would constitute as

severe wear. A BEWE score of 3 (wear affecting over

50% of a surface) present in every sextant constitutes

severe wear. But in an 18-year-old the implication is

greater than that of an older person as the longevity of

the tooth is questionable. Other clinical indicators such

as reduced crown height, compromising the placement

of restorations, could also be classified as severe wear.

Fig. 1 Distinguishing the appearance of unworn to worn teeth in the

If the underlying risk factors can be addressed, then early stages is very difficult. It is only when noticeable changes occur,

wear progression should be slowed and treatment may often with dentine exposure that it can be diagnosed.

not be necessary. This means that for both younger and

older adults, the primary indicator for intervention is

when the patient feels it impacts on their appearance

and self-esteem and would like treatment. The conflict

occurs when severe wear is present in young adults who

request restorations and who are then expecting a life

time of use from their teeth. Conversely, someone

around 70 years old with teeth worn so severely worn

they are unrestorable, suffers the dilemma of either

accepting extractions or no intervention. Neither choice

is wrong as the patient needs to consider their options

and make an informed decision.

In summary, tooth wear is a common experience

and for most, almost a universal outcome of aging. A

relatively small proportion of adults have severe

levels, around 2–4% for younger ages but this Fig. 2 The incisal edge of the upper and lower incisors are often one of

increases to around 10% in old age. the first clinical signs of tooth wear.

surface of the upper incisors. With more progression,

CONSEQUENCES OF TOOTH WEAR

thinning of the palatal or buccal surfaces can lead to

The early signs of change, are clinically, difficult to unsupported enamel resulting in the incisal edges crum-

detect. The signs are subtle and involve loss of surface bling and shorter teeth. At this stage the process

characteristics, cingula, mamellons and smoothing of becomes noticeable to patients (Fig. 3). But at this

facial surfaces (Fig. 1). Distinguishing these changes point other changes to the occlusion occur too. Teeth

from the natural appearance of teeth and then assessing generally tend to maintain contact with opposing teeth.

the surfaces as worn is challenging. Subtle changes can If tooth wear is slow the opposing teeth remain in con-

be readily confused with the natural appearance as tact and a sort of over-eruption occurs. This results in

teeth vary so much. But as the condition progresses, shorted teeth without any space to place restorations

often during early adulthood, in the 20–300 s age group, making rehabilitation very complex to provide. The

the incisal edges of the upper and lower incisors are alveolar compensation can be reversed using principles

worn, leaving a line of dentine exposed (Fig. 2). This such as the Dahl concept5 but it means the restorative

change may reflect the outcome of attrition or its com- process becomes more complex, requires more experi-

bination with erosion but is the first sign that wear has ence from the dentist and costlier to the patient.

developed. Together with the occlusal surfaces of lower

molars these can be considered to be index teeth as they

RESTORATIVE CARE

are generally the first to show signs of change.

As the condition deteriorates, more obvious shape

Prevention

change occurs which become noticeable to dentists.

This can include cupped out lesions, particularly on Most dental healthcare providers tend to focus the

lower first molars, and thinning of the facial/buccal concept of prevention on early wear lesions.

S60 © 2019 Australian Dental Association

Tooth wear and aging

Fig. 3 Changes to the incisal edge lead to shorter teeth. As the palatal

enamel and dentine is worn the loss of support leads to fracture of the teeth.

Prevention is appropriate at any stage of the tooth

wear process, from the early unworn surface to the Figure 4 Composites added to the worn surfaces can rebuild the tooth

shape creating a pleasing image. Their main challenge is maintenance.

most severe wear. Justifiably, most tend to focus on

early intervention, but it should always be kept in

mind that no matter how severe the case, giving pre- months the treatment plan may need to be questioned.

ventive advice may restrict further progression. A recent audit undertaken by the team at Kings College

Most of the preventive actions revolve around tooth- showed that the overall longevity of all restorations

pastes/mouthrinses and dietary modification. There is a was comparable to other studies but individually, teeth

growing body of opinion to suggest that fluoride can or the restorations repeatedly fractured, even after a

either harden enamel surfaces making them more resis- few months.11 Provided the patient accepts this com-

tant to erosion or remineralise newly eroded surfaces.6 promise the acceptability of the restorations remains

It is also possible that different toothpastes act differ- but this might not be acceptable to everyone.

ently at different stages in the erosive process as their

chemical components react differently to enamel.7

Overall, it’s likely that toothpastes, containing fluorides Crowns

or calcium-based products, reduce progression, but Preparing teeth for crowns is destructive and irre-

probably the largest controllable factor is dietary acids. versible. Understandably, for some dentists and patients

We have known for some time that acids can cause ero- this limitation removes their acceptability (Fig. 5), but

sive tooth wear. More recently, the highest risk has they remain an option provided the patient understands

been identified as snacking between meals on dietary what is involved. Once the restorative cycle has started

acids more than two times a day, on acidic beverages, it’s not possible to go back and allow things to deterio-

fruit or fruit-based products.8 Changing diets is a chal- rate again. Under ideal clinical conditions, crowns and

lenge but when successful it should result in the pro- bridges can last 10–15 years and maintenance is less

gression of tooth wear becoming part of the aging onerous. If composite restorations continually fail, they

process and no longer compromising the longevity of need replacing with another technique which only

the teeth.9 leaves crowns. Also, where the tooth wear is severe,

with more than 50% of the crown lost, composites may

Composites

Resin-based composites absorb the underlying colour

of teeth and mimic the natural colour creating a pleas-

ing result (Fig. 4). Additive techniques have proven to

be popular and, on the whole, create an acceptable

result.10 However, increasing clinical evidence suggests

that these brittle materials are liable to fracture and

require replacement which, if it occurs regularly, results

in an expensive and time-consuming process. Many

patients will readily accept a minimal intervention to

preserve tooth tissue to avoid further damage to their

teeth. However, repeated fractures and breakages car-

ries a cost which is borne by the patient and provided Fig. 5 Crowns can improve the appearance of worn teeth but involve

tooth preparation and are not reversible procedures. Unlike composites

this is an irregular expense will be acceptable. How- they have better longevity but if they fail the options to replace them are

ever, if the restorations require replacement after a few more complex.

© 2019 Australian Dental Association S61

D Bartlett and S O’Toole

not survive, particularly if there is an underlying brux- Summary

ism component. The level of experience and confidence

Tooth wear is a universal experience but fortunately

of the dentist makes this care complex.

severe levels, justifying intervention is less common.

An early assessment, at the initial visit, should be

Prevention is the most important intervention,

made on how much tooth tissue remains available for

whether it is with fluoride or other remineralising

conventional crowns. If the tooth height is too short,

solutions or dietary modification. Restorative inter-

additional crown length is needed either from surgical

vention is expensive and at risk of failure because of

repositioning of the gingival tissues or encompassing

the interplay with erosion, attrition and abrasion.

the root within the restoration, utilising posts. How-

ever, if the latter is planned the role of bruxism,

which may be involved with tooth wear, needs consid- REFERENCES

ering as clenching or grinding can overwhelm the 1. Bartlett DW, Lussi A, West NX, Bouchard P, Sanz M, Bour-

materials used to restore teeth. Surgical crown length- geois D. Prevalence of tooth wear on buccal and lingual sur-

ening is uncomfortable for the patient but creates faces and possible risk factors in young European adults. J Dent

2013;41:1007–1013.

optimum crown height provided the periodontal con-

2. Dugmore CR, Rock WP. The prevalence of tooth erosion in 12-

dition is healthy. But if the crown height of teeth is year-old children. Br Dent J 2004;196:279–282.

compromised, then surgical intervention may be the 3. Van’t Spijker A, Rodriguez JM, Kreulen CM, Bronkhorst EM,

only choice remaining to restore the teeth. Bartlett DW, Creugers NH. Prevalence of tooth wear in adults.

Int J Prosthodont 2009;22:35–42.

4. Bartlett D, Ganss C, Lussi A. Basic Erosive Wear Examination

Maintenance (BEWE): a new scoring system for scientific and clinical needs.

Clin Oral Investig 2008;12:65–68.

Once treatment is complete, patients should be aware

5. Gough MB, Setchell D. A retrospective study of 50 treatments

of the need for good oral hygiene, maintain regular using an appliance to produce localised occlusal space by rela-

check-ups and to consume a low cariogenic and acid tive axial tooth movement. Br Dent J 1999;187:134–139.

diet. This is possibly more important in an ageing 6. Austin RS, Rodriguez JM, Dunne S, Moazzez R, Bartlett DW. The

patient. Xerostomia is common in elderly patients and effect of increasing sodium fluoride concentrations on erosion and

attrition of enamel and dentine in vitro. J Dent 2010;38:782–787.

increases the risk of dental caries. Motor skill difficul-

7. O’Toole S, Mistry M, Mutahar M, Moazzez R, Bartlett D.

ties which would impair oral hygiene around restora- Sequence of stannous and sodium fluoride solutions to prevent

tions should be identified from the initial visit and enamel erosion. J Dent 2015;43:1498–1503.

methods to overcome any difficulties discussed. 8. O’Toole S, Bernabe E, Moazzez R, Bartlett D. Timing of diet-

ary acid intake and erosive tooth wear: a case-control study. J

Dent 2017;56:99–104.

Cost 9. O’Toole S, Newton T, Moazzez R, Hasan A, Bartlett D. Ran-

domised controlled clinical trial investigating the impact of

No aspect of dentistry can ignore the impact of cost. implementation planning on behaviour related to the diet. Sci

Tooth wear rarely involves single teeth and more com- Rep 2018;8(1):8024.

monly intervention is justified in multiple sextants or 10. Milosevic A, Burnside G. The survival of direct composite

restorations in the management of severe tooth wear including

quadrants. This factor, combined with the additional attrition and erosion: a prospective 8-year study. J Dent

level of experience needs to carry out complex rehabil- 2016;44:13–19.

itation if indirect restorations are considered, means 11. Bartlett D, Varma S. A retrospective audit of the outcome of

that the management of tooth wear is costly. To com- composites used to restore worn teeth. Br Dent J 2017;223:33–

plicate the situation more, the interplay of bruxism 36.

can risk the survival of restorations meaning that the 12. O’Toole S, Pennington M, Varma S, Bartlett DW. The treat-

ment need and associated cost of erosive tooth wear rehabilita-

longevity associated with a particular material cannot tion-a service evaluation within an NHS dental hospital. Br

be guaranteed as they are liable to fracture or more Dent J 2018;224:957–961.

wear. A recent audit undertaken in the UK estimated

the cost in private practice varied between £4,000 to Address for Correspondence:

£31,000 per case and this did not include maintenance Professor. David Bartlett

costs.12 These figures mean the restorative intervention Department of Prosthodontics

is not universally affordable and so patients need to King’s College London Faculty for Dental

make choices on whether to prevent further damage Oral and Craniofacial Sciences

and monitor change or intervene. Prevention and mon- London Bridge, SE19RT

itoring remain a choice for many patients, even for UK

those who can afford the intervention. Email: david.bartlett@kcl.ac.uk

S62 © 2019 Australian Dental Association

You might also like

- s41415 023 5624 0 LibreDocument6 pagess41415 023 5624 0 LibreAZWATEE BINTI ABDUL AZIZNo ratings yet

- Australian Dental Journal - 2013 - Meyers - Minimum Intervention Dentistry and The Management of Tooth Wear in GeneralDocument6 pagesAustralian Dental Journal - 2013 - Meyers - Minimum Intervention Dentistry and The Management of Tooth Wear in GeneralEdmund KwongNo ratings yet

- Tooth Wear, Etiology, Diagnosis and Its Management in Elderly: A Literature ReviewDocument0 pagesTooth Wear, Etiology, Diagnosis and Its Management in Elderly: A Literature ReviewmegamarwaNo ratings yet

- BSRD Tooth Wear BookletDocument28 pagesBSRD Tooth Wear BookletSalma RafiqNo ratings yet

- Teeth RestorabilityDocument6 pagesTeeth RestorabilityMuaiyed Buzayan AkremyNo ratings yet

- Oral Health: Samuel Zwetchkenbaum, DDS, MPH, and L. Susan Taichman, RDH, MPH, PHDDocument20 pagesOral Health: Samuel Zwetchkenbaum, DDS, MPH, and L. Susan Taichman, RDH, MPH, PHDwesamkhouriNo ratings yet

- Tooth Wear 1Document11 pagesTooth Wear 1Kcl Knit A SocNo ratings yet

- A New Look at Erosive Tooth Wear in Elderly People: JADA 2007 138 (9 Supplement) :21S-25SDocument5 pagesA New Look at Erosive Tooth Wear in Elderly People: JADA 2007 138 (9 Supplement) :21S-25SMarek1964No ratings yet

- Receding Gums, (Gingival Recession) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandReceding Gums, (Gingival Recession) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Leader, Commission - 1998 - Dental ErosionDocument11 pagesLeader, Commission - 1998 - Dental Erosionjanvier_89No ratings yet

- Predictable Management of Cracked Teeth With Reversible PulpitisDocument10 pagesPredictable Management of Cracked Teeth With Reversible PulpitisNaji Z. ArandiNo ratings yet

- Ppad Cortellini PDFDocument9 pagesPpad Cortellini PDFDavid ColonNo ratings yet

- Dental Update 2010. Consequences of Tooth Loss 2. Dentist Considerations Restorative Problems and ImplicationsDocument5 pagesDental Update 2010. Consequences of Tooth Loss 2. Dentist Considerations Restorative Problems and ImplicationsJay PatelNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Dental ErosionDocument10 pagesContemporary Diagnosis and Management of Dental ErosionAndreea AddaNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Considerations in The Elderly: ReviewarticleDocument10 pagesEndodontic Considerations in The Elderly: ReviewarticleYasmine SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Changing Concepts in Cariology - Forty Years OnDocument7 pagesChanging Concepts in Cariology - Forty Years OnDavid CaminoNo ratings yet

- Digital Workflow For The Rehabilitation of The Excessively Worn DentitionDocument26 pagesDigital Workflow For The Rehabilitation of The Excessively Worn Dentitionfloressam2000No ratings yet

- Johannson - Erosion - 2012 PDFDocument18 pagesJohannson - Erosion - 2012 PDFRusevNo ratings yet

- Joor 12972Document10 pagesJoor 12972HristoNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Guide To OrthodonticsDocument77 pagesA Clinical Guide To OrthodonticsSzenyes SzabolcsNo ratings yet

- CrownandExtracoronalRestorations EndodWhitworthDocument11 pagesCrownandExtracoronalRestorations EndodWhitworthMitza CristianNo ratings yet

- Tooth Surface Loss Revisited: Classification, Etiology, and ManagementDocument9 pagesTooth Surface Loss Revisited: Classification, Etiology, and Managementkhalida iftikharNo ratings yet

- Non Carious Tooth Surface LossDocument4 pagesNon Carious Tooth Surface LossmirfanulhaqNo ratings yet

- Tooth WearDocument80 pagesTooth WearrajupangeniNo ratings yet

- Topics of Interest Analyzing The Etiology of An Extremely Worn DentitionDocument10 pagesTopics of Interest Analyzing The Etiology of An Extremely Worn DentitionLuigi BortolottiNo ratings yet

- Caries Risk Assessment and InterventionDocument5 pagesCaries Risk Assessment and InterventionDelia Guadalupe Gardea ContrerasNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To OrthodonticsDocument38 pagesAn Introduction To OrthodonticsSchwan AbdulkareemNo ratings yet

- Sidang Tesis TGL 30 Oktober 2014 Final FixedDocument11 pagesSidang Tesis TGL 30 Oktober 2014 Final Fixedfaizal prabowo KalimanNo ratings yet

- Non Carious LesionsDocument18 pagesNon Carious LesionsAjmal NajeebNo ratings yet

- Abrasi DLLDocument9 pagesAbrasi DLLDiana Gita MentariNo ratings yet

- Need and Demand For TreatmentDocument5 pagesNeed and Demand For TreatmentMohsin HabibNo ratings yet

- TALLER 4selwitz2007Document9 pagesTALLER 4selwitz2007Natalia SplashNo ratings yet

- Lussi - Dec 2006Document7 pagesLussi - Dec 2006Anda MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Pediatricoralandmaxillofacial Surgery: Elizabeth KutcipalDocument16 pagesPediatricoralandmaxillofacial Surgery: Elizabeth KutcipalJamaludin NawawiNo ratings yet

- Fusion/Double Teeth: Sandhya Shrivastava, Manisha Tijare, Shweta SinghDocument3 pagesFusion/Double Teeth: Sandhya Shrivastava, Manisha Tijare, Shweta SinghNurwahit IksanNo ratings yet

- 55 Diagnosis, Prevention and Management of Dental ErosionDocument29 pages55 Diagnosis, Prevention and Management of Dental Erosionraed ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Johnstone Parashos Endodntics and The Ageing PatientDocument8 pagesJohnstone Parashos Endodntics and The Ageing PatientConsultorio Odontologico Dra Yoli PerdomoNo ratings yet

- Dental Attrition - Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment Planning: A ReviewDocument7 pagesDental Attrition - Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment Planning: A ReviewInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Dentine Hypersensitivity - Guidelines For The Management of A Common Oral Health ProblemDocument25 pagesDentine Hypersensitivity - Guidelines For The Management of A Common Oral Health ProblemNaoki MezarinaNo ratings yet

- Oral Rehabilitation With Removable Partial Dentures in Advanced Tooth Loss SituationsDocument7 pagesOral Rehabilitation With Removable Partial Dentures in Advanced Tooth Loss SituationsIoana-NicoletaNicodimNo ratings yet

- Tooth EruptionDocument6 pagesTooth EruptionDr.RajeshAduriNo ratings yet

- 36-1 TunkiwalaDocument16 pages36-1 TunkiwalaSwapnil RastogiNo ratings yet

- MC - Seven Signs and Symptoms of Occlusal DiseaseDocument5 pagesMC - Seven Signs and Symptoms of Occlusal DiseaseMuchlis Fauzi E100% (1)

- Gillborg, 2019Document11 pagesGillborg, 2019GOOSI666No ratings yet

- E775 PDFDocument4 pagesE775 PDFJay PatelNo ratings yet

- Advanced Restorative Dentistry A Problem For The ElderlyDocument8 pagesAdvanced Restorative Dentistry A Problem For The ElderlyAli Faridi100% (1)

- Cracked Tooth SyndromDocument9 pagesCracked Tooth Syndromzeina32No ratings yet

- 8-Treatment of Deep Caries, Vital Pulp Exposure, Pulpless TeethDocument8 pages8-Treatment of Deep Caries, Vital Pulp Exposure, Pulpless TeethAhmed AbdNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 02 HistoryDocument13 pagesCHAPTER 02 Historyمحمد حسنNo ratings yet

- Tooth Wear An Authoritative Reference For Dental Professionals and Students (Andrew Eder, Maurice Faigenblum, (Eds.) ) (Z-Library)Document313 pagesTooth Wear An Authoritative Reference For Dental Professionals and Students (Andrew Eder, Maurice Faigenblum, (Eds.) ) (Z-Library)Diego DuranNo ratings yet

- Rea (DMD6B) - Midterm Journal #1Document2 pagesRea (DMD6B) - Midterm Journal #1Jamm ReaNo ratings yet

- The Contributions of Craniofacial Growth To Clinical OrthodonticsDocument3 pagesThe Contributions of Craniofacial Growth To Clinical OrthodonticsLibia Adriana Montero HincapieNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Consent FormDocument3 pagesOrthodontic Consent FormDiana Suharti100% (1)

- ODTP - 4 Tooth Surface LossDocument7 pagesODTP - 4 Tooth Surface LossDr-Mohamed KandeelNo ratings yet

- Developmental Enamel Defects in Primary DentitionDocument8 pagesDevelopmental Enamel Defects in Primary DentitionAndrea LawNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3 - Cells and Organs IIDocument30 pagesLecture 3 - Cells and Organs IIAhmed Examination100% (1)

- 7.uprighting Molars Without ExtrusionDocument5 pages7.uprighting Molars Without ExtrusionMaria SilvaNo ratings yet

- DR Nick Lekic - Space MaintainersDocument35 pagesDR Nick Lekic - Space MaintainersanatomimanusiaNo ratings yet

- Heart Physiology: Nabila Alifah Zahra Perkasa 1610211096Document35 pagesHeart Physiology: Nabila Alifah Zahra Perkasa 1610211096putri avriantiNo ratings yet

- CH 9, 10 - Questions - TRANSPORT IN ANIMALS, DISEASES AND IMMUNITYDocument22 pagesCH 9, 10 - Questions - TRANSPORT IN ANIMALS, DISEASES AND IMMUNITYPranitha RaviNo ratings yet

- Frogdissection PDFDocument11 pagesFrogdissection PDFSip BioNo ratings yet

- Body Fluids and Circulation - Mind Maps - Arjuna NEET 2024Document5 pagesBody Fluids and Circulation - Mind Maps - Arjuna NEET 2024aashish.tskauthNo ratings yet

- Tooth IdentificationDocument26 pagesTooth Identificationapi-3820481100% (3)

- DigestiveSystem Lesson Plan in ScienceDocument7 pagesDigestiveSystem Lesson Plan in ScienceRandy50% (4)

- Hebb 1949Document16 pagesHebb 1949Norel Nicolae BalutaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Elements For Tooth Extraction in OrthodonticsDocument24 pagesDiagnostic Elements For Tooth Extraction in OrthodonticsLanaNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 8 Feb 2022-1Document8 pagesAdobe Scan 8 Feb 2022-1BHASWAT GAMINGNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Water Metabolism and Diabetes InsipidusDocument36 pagesChapter 1 - Water Metabolism and Diabetes InsipidusSteffi AraujoNo ratings yet

- ANATOMY OF GUINEA PIG (Cavia Porcellus)Document8 pagesANATOMY OF GUINEA PIG (Cavia Porcellus)Daisy KavinskyNo ratings yet

- Endocrine ConditionsDocument5 pagesEndocrine ConditionsGlen DizonNo ratings yet

- Adverse Effects of Orthodontic Treatment PDFDocument5 pagesAdverse Effects of Orthodontic Treatment PDFcareNo ratings yet

- Tooth Mould ChartDocument12 pagesTooth Mould ChartJoohi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ricketts Visual Treatment Objective & SuperimpositionDocument25 pagesRicketts Visual Treatment Objective & SuperimpositionAnonymous SJ4w0os100% (1)

- Neuroendocrine of CrustaceaDocument29 pagesNeuroendocrine of CrustaceaAnirudh Acharya100% (1)

- Drug Distribution (Kinetika Farmakokinetik)Document14 pagesDrug Distribution (Kinetika Farmakokinetik)princessaurora1998No ratings yet

- BP201TPDocument1 pageBP201TPDarshanNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Regulation and Integration: Mcardle, Katch, and Katch: Exercise Physiology: EnergyDocument24 pagesCardiovascular Regulation and Integration: Mcardle, Katch, and Katch: Exercise Physiology: EnergyamrendraNo ratings yet

- Urodynamic Testing ReportDocument25 pagesUrodynamic Testing Reportzharah180% (1)

- Blood: Joanna Gwen F. FabreroDocument28 pagesBlood: Joanna Gwen F. FabreroAlan PeterNo ratings yet

- IGCSE Biology Transport in Animals NotesDocument62 pagesIGCSE Biology Transport in Animals NotesSir AhmedNo ratings yet

- I MCQs Neuro.Document4 pagesI MCQs Neuro.Mhmd Iraky100% (1)

- Lympathic System TransesDocument9 pagesLympathic System TransesMonica SabarreNo ratings yet

- Physiology Question Bank FinalDocument16 pagesPhysiology Question Bank Finalatefmabood100% (2)

- Class II Division 2 MalocclusionDocument8 pagesClass II Division 2 MalocclusionIddi IddiNo ratings yet

- Dental VtoDocument10 pagesDental VtoDevata RaviNo ratings yet