Professional Documents

Culture Documents

England From The Civil War To Commonwealth

Uploaded by

Laour Mohammed0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views8 pagesOriginal Title

England from the Civil War to Commonwealth

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views8 pagesEngland From The Civil War To Commonwealth

Uploaded by

Laour MohammedCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

England from the Civil War to Commonwealth

1. England during the Civil Wars.

English Civil Wars, also called Great Rebellion, (1642–51), fighting that took place in the

British Isles between supporters of the monarchy of Charles I (and his son and successor,

Charles II) and opposing groups in each of Charles's kingdoms, including Parliamentarians in

England, Covenanters in Scotland, and Confederates in Ireland. The civil wars are traditionally

considered to have begun in England in August 1642, when Charles I raised an army against

the wishes of Parliament, ostensibly to deal with a rebellion in Ireland. But the period of conflict

actually began earlier in Scotland, with the Bishops' Wars of 1639–40, and in Ireland, with the

Ulster rebellion of 1641. Throughout the 1640s, war between king and Parliament ravaged

England, but it also struck all of the kingdoms held by the House of Stuart—and, in addition to

war between the various British and Irish dominions, there was civil war within each of the

Stuart states. For this reason the English Civil Wars might more properly be called the British

Civil Wars or the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The wars finally ended in 1651 with the flight

of Charles II to France and, with him, the hopes of the British monarchy.

Personal Rule and the seeds of rebellion (1629–40)

Compared to the chaos unleashed by the Thirty Years' War (1618–48) on the European

continent, the British Isles under Charles I enjoyed relative peace and economic prosperity

during the 1630s. However, by the later 1630s, Charles's regime had become unpopular across

a broad front throughout his kingdoms. During the period of his so-called Personal Rule (1629–

40), known by his enemies as the “Eleven Year Tyranny” because he had dissolved Parliament

and ruled by decree, Charles had resorted to dubious fiscal expedients, most notably “ship

money,” an annual levy for the reform of the navy that in 1635 was extended from English ports

to inland towns. This inclusion of inland towns was construed as a new tax without

parliamentary authorization. When combined with ecclesiastical reforms undertaken by

Charles's close adviser William Laud, the archbishop of Canterbury, and with the conspicuous

role assumed in these reforms by Henrietta Maria, Charles's Catholic queen, and her courtiers,

many in England became alarmed. Nevertheless, despite grumblings, there is little doubt that

had Charles managed to rule his other dominions as he controlled England, his peaceful reign

might have been extended indefinitely. Scotland and Ireland proved his undoing.

In 1633 Thomas Wentworth became lord deputy of Ireland and set out to govern that country

without regard for any interest but that of the crown. His thorough policies aimed to make

Ireland financially self-sufficient; to enforce religious conformity with the Church of England

as defined by Laud, Wentworth's close friend and ally; to “civilize” the Irish; and to extend

royal control throughout Ireland by establishing British plantations and challenging Irish titles

to land. Wentworth's actions alienated both the Protestant and the Catholic ruling elites in

Ireland. In much the same way, Charles's willingness to tamper with Scottish land titles

unnerved landowners there. However, it was Charles's attempt in 1637 to introduce a modified

version of the English Book of Common Prayer that provoked a wave of riots in Scotland,

beginning at the Church of St. Giles in Edinburgh. A National Covenant calling for immediate

withdrawal of the prayer book was speedily drawn up on Feb. 28, 1638. Despite its moderate

tone and conservative format, the National Covenant was a radical manifesto against the

Personal Rule of Charles I that justified a revolt against the interfering sovereign.

The Bishops' Wars and the return of Parliament (1640–42)

The turn of events in Scotland horrified Charles, who determined to bring the rebellious Scots

to heel. However, the Covenanters, as the Scottish rebels became known, quickly overwhelmed

the poorly trained English army, forcing the king to sign a peace treaty at Berwick (June 18,

1639). Though the Covenanters had won the first Bishops' War, Charles refused to concede

victory and called an English parliament, seeing it as the only way to raise money quickly.

Parliament assembled in April 1640, but it lasted only three weeks (and hence became known

as the Short Parliament). The House of Commons was willing to vote the huge sums that the

king needed to finance his war against the Scots, but not until their grievances—some dating

back more than a decade—had been redressed. Furious, Charles precipitately dissolved the

Short Parliament. As a result, it was an untrained, ill-armed, and poorly paid force that trailed

north to fight the Scots in the second Bishops' War. On Aug. 20, 1640, the Covenanters invaded

England for the second time, and in a spectacular military campaign they took Newcastle

following the Battle of Newburn (August 28). Demoralized and humiliated, the king had no

alternative but to negotiate and, at the insistence of the Scots, to recall parliament.

A new parliament (the Long Parliament), which no one dreamed would sit for the next 20 years,

assembled at Westminster on Nov. 3, 1640, and immediately called for the impeachment of

Wentworth, who by now was the Earl of Strafford. The lengthy trial at Westminster, ending

with Strafford's execution on May 12, 1641, was orchestrated by Protestants and Catholics from

Ireland, by Scottish Covenanters, and by the king's English opponents, especially the leader of

Commons, John Pym—effectively highlighting the importance of the connections between all

the Stuart kingdoms at this critical junction.

To some extent, the removal of Strafford's draconian hand facilitated the outbreak in October

1641 of the Ulster uprising in Ireland. This rebellion derived, on the one hand, from long-term

social, religious, and economic causes (namely tenurial insecurity, economic instability,

indebtedness, and a desire to have the Roman Catholic Church restored to its pre-Reformation

position) and, on the other hand, from short-term political factors that triggered the outbreak of

violence. Inevitably, bloodshed and unnecessary cruelty accompanied the insurrection, which

quickly engulfed the island and took the form of a popular rising, pitting Catholic natives

against Protestant newcomers. The extent of the “massacre” of Protestants was exaggerated,

especially in England where the wildest rumours were readily believed. Perhaps 4,000 settlers

lost their lives—a tragedy to be sure, but a far cry from the figure of 154,000 the Irish

government suggested had been butchered. Much more common was the plundering and

pillaging of Protestant property and the theft of livestock. These human and material losses

were replicated on the Catholic side as the Protestants retaliated.

The Irish insurrection immediately precipitated a political crisis in England, as Charles and his

Westminster Parliament argued over which of them should control the army to be raised to quell

the Irish insurgents. Had Charles accepted the list of grievances presented to him by Parliament

in the Grand Remonstrance of December 1641 and somehow reconciled their differences, the

revolt in Ireland almost certainly would have been quashed with relative ease. Instead, Charles

mobilized for war on his own, raising his standard at Nottingham in August 1642. The Wars of

the Three Kingdoms had begun in earnest. This also marked the onset of the first English Civil

War fought between forces loyal to Charles I and those who served Parliament. After a period

of phony war late in 1642, the basic shape of the English Civil War was of Royalist advance in

1643 and then steady Parliamentarian attrition and expansion.

The first English Civil War (1642–46)

The first major battle fought on English soil—the Battle of Edgehill (October 1642)—quickly

demonstrated that a clear advantage was enjoyed by neither the Royalists (also known as the

Cavaliers) nor the Parliamentarians (also known as the Roundheads for their short-cropped hair,

in contrast to the long hair and wigs associated with the Cavaliers). Although recruiting,

equipping, and supplying their armies initially proved problematic for both sides, by the end of

1642 each had armies of between 60,000 and 70,000 men in the field. However, sieges and

skirmishes—rather than pitched battles—dominated the military landscape in England during

the first Civil War, as local garrisons, determined to destroy the economic basis of their

opponents while preserving their own resources, scrambled for territory. Charles, with his

headquarters in Oxford, enjoyed support in the north and west of England, in Wales, and (after

1643) in Ireland. Parliament controlled the much wealthier areas in the south and east of

England together with most of the key ports and, critically, London, the financial capital of the

kingdom. In order to win the war, Charles needed to capture London, and this was something

that he consistently failed to do.

Yet Charles prevented the Parliamentarians from smashing his main field army. The result was

an effective military stalemate until the triumph of the Roundheads at the Battle of Marston

Moor (July 2, 1644). This decisive victory deprived the king of two field armies and, equally

important, paved the way for the reform of the parliamentary armies with the creation of the

New Model Army, completed in April 1645. Thus, by 1645 Parliament had created a centralized

standing army, with central funding and central direction. The New Model Army now moved

against the Royalist forces. Their closely fought victory at the Battle of Naseby (June 14, 1645)

proved the turning point in parliamentary fortunes and marked the beginning of a string of

stunning successes—Langport (July 10), Rowton Heath (September 24), and Annan Moor

(October 21)—that eventually forced the king to surrender to the Scots at Newark on May 5,

1646.

It is doubtful whether Parliament could have won the first English Civil War without Scottish

intervention. Royalist successes in England in the spring and early summer of 1643, combined

with the prospect of aid from Ireland for the king, prompted the Scottish Covenanters to sign a

political, military, and religious alliance—the Solemn League and Covenant (Sept. 25, 1643)—

with the English Parliamentarians. Desperate to protect their revolution at home, the

Covenanters insisted upon the establishment of Presbyterianism in England and in return agreed

to send an army of 21,000 men to serve there. These troops played a critical role at Marston

Moor, with the covenanting general, David Leslie, briefly replacing a wounded Oliver

Cromwell in the midst of the action. For his part, Charles looked to Ireland for support.

However, the Irish troops that finally arrived in Wales after a cease-fire was concluded with the

confederates in September 1643 never equaled the Scottish presence, while the king's

willingness to secure aid from Catholic Ireland sullied his reputation in England.

Conflicts in Scotland and Ireland

The presence of a large number of Scottish troops in England should not detract from the fact

that Scots experienced their own domestic conflict after 1638. In Scotland loyalty to the

Covenant, the king, and the House of Argyll resulted in a lengthy and, at times, bloody civil

war that began in February 1639, when the Covenanters seized Inverness, and ended with the

surrender of Dunnottar castle, near Aberdeen, in May 1652. Initially, the Scottish Royalists

under the command of James Graham, earl of Montrose, won a string of victories at Tippermuir

(Sept. 1, 1644), Aberdeen (September 13), Inverlochy (Feb. 2, 1645), Auldearn (May 9), Alford

(July 2), and Kilsyth (August 15) before being decisively routed by the Covenanters at

Philiphaugh (September 13).

Like Scotland, Ireland fought its own civil war (also known as the Confederate Wars). Between

1642 and 1649, the Irish Confederates, with their capital at Kilkenny, directed the Catholic war

effort, while James Butler, earl of Ormonde, commanded the king's Protestant armies. In

September 1643, the two sides concluded a cease-fire, but they failed to negotiate a lasting

political and religious settlement acceptable to all parties.

Second and third English Civil Wars (1648–51)

While the Scottish Covenanters had made a significant contribution to Parliament's victory in

the first English Civil War, during the second (1648) and third English Civil Wars (1650–51)

they supported the king. On Dec. 26, 1647, Charles signed an agreement—known as the

Engagement—with a number of leading Covenanters. In return for the establishment of

Presbyterianism in England for a period of three years, the Scots promised to join forces with

the English Royalists and restore the king to his throne. Early in July 1648, a Scottish force

invaded England, but the parliamentary army routed it at the Battle of Preston (August 17).

The execution of Charles I in January 1649 merely served to galvanize Scottish (and Irish)

support for the king's son, Charles II, who was crowned king of the Scots at Scone, near Perth,

on Jan. 1, 1651. Ultimately, the defeat of a combined force of Irish Royalists and Confederates

at the hands of English Parliamentarians after August 1649 prevented the Irishmen from serving

alongside their Scottish and English allies in the third English Civil War. As it was, this war

was largely fought on Scottish soil, Oliver Cromwell and his New Model Army having invaded

Scotland in July 1650. Despite being routed at the Battle of Dunbar (Sept. 3, 1650), which

Cromwell regarded as “one of the most signal mercies God hath done for England and His

people,” the Scots managed to raise another army that made a spectacular dash into England.

This wild attempt to capture London came to nothing. Cromwell's resounding victory at

Worcester (Sept. 3, 1651) and Charles II's subsequent flight to France not only gave Cromwell

control over England but also effectively ended the wars of—and the wars in—the three

kingdoms.

Cost and legacy

While it is notoriously difficult to determine the number of casualties in any war, it has been

estimated that the conflict in England and Wales claimed about 85,000 lives in combat, with a

further 127,000 noncombat deaths (including some 40,000 civilians). The fighting in Scotland

and Ireland, where the populations were roughly a fifth of that of England, was more brutal

still. As many as 15,000 civilians perished in Scotland, and a further 137,000 Irish civilians

may well have died as a result of the wars there. In all nearly 200,000 people, or roughly 2.5

percent of the civilian population, lost their lives directly or indirectly as a result of the Wars of

the Three Kingdoms during this decade, making the Civil Wars arguably the bloodiest conflict

in the history of the British Isles.

These were the last civil wars ever fought on English—but not Scottish or Irish—soil, and they

have bequeathed a lasting legacy. Ever since this period, the peoples of the three kingdoms have

had a profound distrust of standing armies, while ideas first mooted during the 1640s,

particularly about religious toleration and limitations on power, have survived to this day.

2. Commonwealth and Protectorate

The execution of the king aroused hostility not only in England but also throughout Europe.

Regicide was considered the worst of all crimes, and not even the brilliance of John Milton in

The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1649) could persuade either Catholic or Protestant

powers that the execution of Charles I was just. Open season was declared against English

shipping, and Charles II was encouraged to reclaim his father's three kingdoms.

Despite opposition and continued external threats, the government of the Commonwealth was

declared in May 1649 after acts had been passed to abolish the monarchy and the House of

Lords. Political power resided in a Council of State, the Rump Parliament (which swelled from

75 to 213 members in the year following the king's execution), and the army. The military was

now a permanent part of English government. Though the soldiers had assigned the complex

tasks of reform to Parliament, they made sure of their ability to intervene in political affairs.

At first, however, the soldiers had other things to occupy them. For reasons of security and

revenge, Ireland had to be pacified. In the autumn of 1649, Cromwell crossed to Ireland to deal

once and for all with the Irish Confederate rebels. He came first to Drogheda. When the town

refused to surrender, he stormed it and put the garrison of 3,000 to the sword, acting both as the

avenger of the massacres of 1641 (“I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgement of God

upon those barbarous wretches who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood”) and

as a deliberate instrument of terror to induce others to surrender. He repeated his policy of

massacre at Wexford, this time choosing not to spare the civilian population. These actions had

the desired effect, and most other towns surrendered at Cromwell's approach. He departed

Ireland after nine months, leaving his successors with only a mopping-up operation. His

reputation at a new high, Cromwell was next put in charge of dealing with those Scots who had

welcomed Charles I's son, Charles II, to Scotland and who were soon to crown him at Scone as

king of all of Great Britain and Ireland. Although outnumbered and in a weak defensive

position, Cromwell won a stunning victory in the Battle of Dunbar on Sept. 3, 1650. A year

later to the day, having chased Charles II and a second Scottish army into England, he gained

an overwhelming victory at Worcester. Charles II barely escaped with his life.

Victorious wars against the Irish, Scots, and Dutch (1652) made the Commonwealth a feared

military power. But the struggle for survival defined the Rump's conservative policies. Little

was done to reform the law. An attempt to abolish the court of chancery created chaos in the

central courts. Little agreement could be reached on religious matters, especially on the vexing

question of the compulsory payment of tithes. The Rump failed both to make long-term

provision for a new “national church” and to define the state's right to confer and place limits

on the freedom of those who wished to worship and gather outside the church. Most ominously,

nothing at all had been done to set a limit for the sitting of the Rump and to provide for franchise

reform and the election of a new Parliament. This had been the principal demand of the army,

and the more the Rump protested the difficulty of the problem, the less patient the soldiers

became. In April, when it was clear that the Rump would set a limit to its sitting but would

nominate its own members to judge new elections, Cromwell marched to Westminster and

dissolved Parliament. The Rump was replaced by an assembly nominated mostly by the army

high command. The Nominated Parliament (1653) was no better able to overcome its internal

divisions or untangle the threads of reform than the Rump. After five months it dissolved itself

and returned power to Cromwell and the army.

The problems that beset both the Rump and the Nominated Parliament resulted from the

diversity of groups that supported the revolution, ranging from pragmatic men of affairs,

lawyers, officeholders, and local magistrates whose principal desire was to restore and maintain

order to zealous visionaries who wished to establish heaven on earth. The republicans, like Sir

Henry Vane the Younger, hoped to create a government based upon the model of ancient Rome

and modern Venice. They were proud of the achievements of the Commonwealth and reviled

Cromwell for dissolving the Rump. But most political reformers based their programs on

dreams of the future rather than the past. They were millenarians, expecting the imminent

Second Coming of Christ. Some were social reformers, such as Gerrard Winstanley, whose

followers, agrarian communists known as Diggers, believed that the common lands should be

returned to the common people. Others were mystics, such as the Ranters, led by Laurence

Claxton, who believed that they were infused with a holy spirit that removed sin from even their

most reprehensible acts. The most enduring of these groups were the Quakers (Society of

Friends), whose social radicalism was seen in their refusal to take oaths or doff their hats and

whose religious radicalism was contained in their emphasis upon inner light. Ultimately, all

these groups were persecuted by successive revolutionary governments, which were continually

being forced to establish conservative limits to individual and collective behaviour.

The failure of the Nominated Parliament led to the creation of the first British constitution, the

Instrument of Government (1653). Drafted by Maj. Gen. John Lambert, the Instrument created

a lord protector, a Council of State, and a reformed Parliament that was to be elected at least

once every three years. Cromwell was named protector, and he chose a civilian-dominated

Council to help him govern. The Protectorate tackled many of the central issues of reform head-

on. Commissions were appointed to study law reform and the question of tithes. Social

legislation against swearing, drunkenness, and stage plays was introduced. Steps were taken to

provide for the training of a godly ministry, and even a new university at Durham was begun.

But the protector was no better able to manage his Parliaments than had been the king. The

Parliament of 1654 immediately questioned the entire basis of the newly established

government, with the republicans vigorously disputing the office of lord protector. The

Parliament of 1656, despite the exclusion of many known opponents, was no more pliable. Both

were a focus for the manifold discontents of supporters and opponents of the regime.

Nothing was more central to the Cromwellian experiment than the cause of religious liberty.

Cromwell believed that no one church had a monopoly on truth and that no one form of

government or worship was necessary or desirable. Moreover, he believed in a loosely federated

national church, with each parish free to worship as it wished within very broad limits and

staffed by a clergy licensed by the state on the basis of their knowledge of the Bible and the

uprightness of their lives, without reference to their religious beliefs. On the other hand,

Cromwell felt that there should be freedom for “all species of protestant” to gather if they

wished into religious assemblies outside the national church. He did not believe, however, that

religious liberty was a natural right, but one conferred by the Christian magistrate, who could

place prudential limits on the exercise of that liberty. Thus, those who claimed that their religion

permitted or even promoted licentiousness and sexual freedom, who denied the Trinity, or who

claimed the right to disrupt the worship of others were subject to proscription or penalty.

Furthermore, for the only time between the Reformation and the mid-19th century, there was

no religious test for the holding of public office. Although Cromwell made his detestation of

Catholicism very plain, Catholics benefited from the repeal of the laws requiring attendance at

parish churches, and they were less persecuted for the private exercise of their own faith than

at any other time in the century. Cromwell's policy of religious tolerance was far from total, but

it was exceptional in the early modern world.

Among opponents, royalists were again active, though by now they were reduced to secret

associations and conspiracies. In the west, Penruddock's rising, the most successful of a series

of otherwise feeble royalist actions in March 1655, was effectively suppressed, but Cromwell

reacted by reducing both the standing army and the level of taxation on all. He also appointed

senior army officers “major generals,” raising ultra-loyal militias from among the demobbed

veterans paid for by penal taxation on all those convicted of active royalism in the previous

decade. The major generals were also charged with superintending “a reformation of

manners”—the imposition of strict Puritan codes of social and sexual conduct. They were

extremely unpopular, and, despite their effectiveness, the offices were abolished within a year.

By now it was apparent that the regime was held together by Cromwell alone. Within his

personality resided the contradictions of the revolution. Like the gentry, he desired a fixed and

stable constitution, but, like the zealous, he was infused with a millenarian vision of a more

glorious world to come (see millennialism). As a member of Parliament from 1640, he respected

the fundamental authority that Parliament represented, but, as a member of the army, he

understood power and the decisive demands of necessity. In the 1650s many wished him to

become king, but he refused the crown, preferring the authority of the people to the authority

of the sword. When he died in 1658, all hope of continued reform died with him.

For a time, Richard Cromwell was elevated to his father's titles and dignity, but he was no match

in power or skill. The republicans and the army officers who had fought Oliver tooth and nail

now hoped to use his son to dismantle the civil government that under the Humble Petition and

Advice (1657) had come to resemble nothing so much as the old monarchy. An upper House

of Lords had been created, and the court at Whitehall was every bit as ceremonious as that of

the Stuarts. While some demanded that the Rump be restored to power, others clamoured for

the selection of a new Parliament on the basis of the old franchise, and this took place in 1659.

By then there was a vacuum of power at the centre; Richard Cromwell, incapable of governing,

simply left office. A rebellion of junior officers led to the reestablishment of the Rump.

But all was confusion. The Rump was incapable of governing without financial support from

the City and military support from the army. Just as in 1647, the City demanded military

disbandment and the army demanded satisfaction of its material grievances. But the army was

no longer a unified force. Contentions among the senior officers led to an attempt to arrest

Lambert, and the widely scattered regiments had their own grievances to propound. The most

powerful force was in Scotland, commanded by George Monck, once a royalist and now one

of the ablest of the army's senior officers. When one group of officers determined to dissolve

the Rump, Monck marched his forces south, determined to restore it. Arriving in London,

Monck quickly realized that the Rump could never govern effectively and that only the

restoration of Charles II could put an end to the political chaos that now gripped the state. In

February 1660 Monck reversed Pride's Purge, inviting all of the secluded members of the Long

Parliament to return to their seats under army protection. A month later the Long Parliament

dissolved itself, paving the way for the return of the king.

Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Your English Pal ESL Lesson Plan War Peace Student v1Document4 pagesYour English Pal ESL Lesson Plan War Peace Student v1Alina YefimenkoNo ratings yet

- Concept of State Digested CasesDocument14 pagesConcept of State Digested CasessheldoncooperNo ratings yet

- Cyber Threat Intelligence PlanDocument8 pagesCyber Threat Intelligence Planapi-427997860No ratings yet

- XCambridge History Slavery Vol 1Document575 pagesXCambridge History Slavery Vol 1jicvan49100% (15)

- WORKSHEET - Organizational PatternsDocument2 pagesWORKSHEET - Organizational PatternsLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Natural Disasters Flashcards - 105898Document12 pagesNatural Disasters Flashcards - 105898Laour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Man and Nature 2 Natural Disassters Conversation Topics Dialogs - 132575Document10 pagesMan and Nature 2 Natural Disassters Conversation Topics Dialogs - 132575Laour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Irregular Verbs Jeopardy Activities Promoting Classroom Dynamics Group Form 48039Document51 pagesIrregular Verbs Jeopardy Activities Promoting Classroom Dynamics Group Form 48039Laour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Natural Disasters I Picture Dictionaries - 111493Document10 pagesNatural Disasters I Picture Dictionaries - 111493Laour MohammedNo ratings yet

- The Business Unit 1 Building A CareerDocument3 pagesThe Business Unit 1 Building A CareerLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Student Handout: Identifying Offense vs. Defense in Debate Handout #3Document2 pagesStudent Handout: Identifying Offense vs. Defense in Debate Handout #3Laour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Unit 8Document9 pagesUnit 8Laour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Occep 1 InstructionsstudyguideDocument7 pagesOccep 1 InstructionsstudyguideLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Come Back To SchoolDocument2 pagesCome Back To SchoolLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Presentation Worksheet: Prepare Practice Present PerfectDocument3 pagesPresentation Worksheet: Prepare Practice Present PerfectLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Presentation Feedback SheetDocument6 pagesPresentation Feedback SheetLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Speech Outline Example I TGbYbfcDocument3 pagesSpeech Outline Example I TGbYbfcLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Component 2S: Depth Study: The Making of Modern Britain, 1951-2007 Part One: Building A New Britain, 1951-1979Document5 pagesComponent 2S: Depth Study: The Making of Modern Britain, 1951-2007 Part One: Building A New Britain, 1951-1979Laour MohammedNo ratings yet

- What's Review of LiteratureDocument15 pagesWhat's Review of LiteratureLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Teaching Civilisation: Approaches and MethodsDocument22 pagesTeaching Civilisation: Approaches and MethodsLaour MohammedNo ratings yet

- Battle of Fraustadt, 1706 Feb 13Document6 pagesBattle of Fraustadt, 1706 Feb 13fiorenzorNo ratings yet

- 4th Generation Warfare HandbookDocument401 pages4th Generation Warfare HandbookBaizuo VictimologistNo ratings yet

- From The End of The Cold War To A New World Dis-Order?: Michael CoxDocument14 pagesFrom The End of The Cold War To A New World Dis-Order?: Michael CoxМинура МирсултановаNo ratings yet

- Education, Government and LawDocument7 pagesEducation, Government and LawMaria Mahal AbiaNo ratings yet

- GROUP2 American Made HeroDocument3 pagesGROUP2 American Made HeroJA KENo ratings yet

- 9th Class Social Science Socialism in EuropeDocument18 pages9th Class Social Science Socialism in EuropeAbhishek SinghNo ratings yet

- Player's Guide To Fighters and BarbariansDocument146 pagesPlayer's Guide To Fighters and BarbariansJuan MonsalveNo ratings yet

- John Brown DBQDocument2 pagesJohn Brown DBQangela100% (4)

- Amzah Ibn Abdul-Mu Alib Was A: Nabī Asad Allāh JannahDocument1 pageAmzah Ibn Abdul-Mu Alib Was A: Nabī Asad Allāh JannahMeasam TVNo ratings yet

- Cry of Pugad LawinDocument18 pagesCry of Pugad LawinNoel MarquezNo ratings yet

- The Ottoman EmpireDocument136 pagesThe Ottoman EmpiregnostikbreNo ratings yet

- April Carter - Political Theory of Anarchism (1971, Law Book Co of Australasia) PDFDocument124 pagesApril Carter - Political Theory of Anarchism (1971, Law Book Co of Australasia) PDFFelipe RichardiosNo ratings yet

- Supplementary Report Bahá'ís of Iran 2010Document15 pagesSupplementary Report Bahá'ís of Iran 2010Jheniefeer SayyáhNo ratings yet

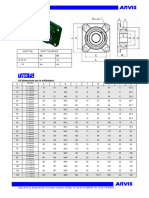

- Arvis Bearing FL MetricDocument1 pageArvis Bearing FL MetricNMBaihakiARNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21-The Age of NapoleonDocument18 pagesChapter 21-The Age of NapoleonJonathan Daniel KeckNo ratings yet

- Field Artillery Journal - Nov 1936Document99 pagesField Artillery Journal - Nov 1936CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- History of Peru ......Document10 pagesHistory of Peru ......koem phannyNo ratings yet

- Released in Full: UncluwtassifiedDocument13 pagesReleased in Full: UncluwtassifiedSergio SanzNo ratings yet

- Age of Mythology Unit StatisticsDocument11 pagesAge of Mythology Unit Statisticstoney lukaNo ratings yet

- The Leadership JourneyDocument107 pagesThe Leadership JourneyPaul100% (1)

- Marele Zid Chinezesc 2021Document1 pageMarele Zid Chinezesc 2021Frasie SergiuNo ratings yet

- GooglepreviewDocument49 pagesGooglepreviewshumi belayNo ratings yet

- International Economics 16th Edition Carbaugh Solutions ManualDocument24 pagesInternational Economics 16th Edition Carbaugh Solutions ManualTylerArcherrgcax100% (57)

- Military - Arms & Accoutrements - Swords - Hunting Swords & CuttoesDocument43 pagesMilitary - Arms & Accoutrements - Swords - Hunting Swords & CuttoesThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (2)

- José Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonso RealondaDocument2 pagesJosé Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonso RealondaJames ArriolaNo ratings yet

- Digimon World 2 Game SharkDocument17 pagesDigimon World 2 Game Sharkcorona_2013No ratings yet