Professional Documents

Culture Documents

9 Content Based Restriction of The Freedom of Expression

Uploaded by

Anonymous VtsflLix10 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views2 pages9 CONTENT BASED RESTRICTION OF THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Original Title

9 CONTENT BASED RESTRICTION OF THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document9 CONTENT BASED RESTRICTION OF THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views2 pages9 Content Based Restriction of The Freedom of Expression

Uploaded by

Anonymous VtsflLix19 CONTENT BASED RESTRICTION OF THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

CONTENT BASED RESTRICTION OF

THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Content-based restrictions regulate speech based on its subject matter

or viewpoint. They seek to “suppress, disadvantage, or impose

differential burdens upon speech because of its content.”[1] Justice

Holmes, in one of his most famous opinions, wrote:

“ The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man

in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic. . . . The

question in every case is whether the words used . . . create a clear and

present danger. . . .[2] ”

Analysis

In its current formulation of this principle, the Supreme Court held that

“advocacy of the use of force or of law violation” is protected unless

“such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless

action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”[3] Similarly, the

Court held that a statute prohibiting threats against the life of the

President could be applied only against speech that constitutes a “true

threat,” and not against mere “political hyperbole.”[4]

In cases of content-based restrictions of speech other than advocacy or

threats, such regulations are presumptively invalid.[5] The Supreme

Court generally has applies the “strict scrutiny” standard, which means

that it will uphold a content-based restriction only if it is necessary “to

promote a compelling interest,” and is “the least restrictive means to

further the articulated interest.”[6]

Thus, it is ordinarily unconstitutional for a state to proscribe a

newspaper from publishing the name of a rape victim, lawfully obtained.

[7] This is because there ordinarily is no compelling governmental

interest in protecting a rape victim’s privacy.[8]

By contrast, “[n]o one would question but that a government might

prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of

the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops.”[9]

Similarly, the government may proscribe “‘fighting’ words — those which

by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach

of the peace.”[10] Here the Court was referring to utterances that

constitute “epithets or personal abuse” that “are no essential part of any

exposition of ideas,” as opposed to, for example, flag burning.

The operative distinctions between a court’s review of a content-based

restrictions and a content-neutral restrictions is that in the former case,

the government must meet the “compelling interest” and “least

restrictive means” standards, while in the latter situation the government

need only prove a “significant interest” and the availability of “ample

alternative channels for communication of the information.”

Constitutional scholars generally agree that governmental regulation of

media products with violent content, “whether in the form of banning,

rating, or channeling of violent media content, necessarily requires the

government to make a judgment as to what content lies within the ambit

of the statute and what content does not,” thereby triggering content-

based strict scrutiny review.[11]

You might also like

- Transportation LawsDocument125 pagesTransportation LawsDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Jugueta, G.R. No. 202124, 5 April 2016Document37 pagesPeople vs. Jugueta, G.R. No. 202124, 5 April 2016Kassandra Czarina PedrozaNo ratings yet

- People vs. AnchetaDocument3 pagesPeople vs. AnchetaJian CerreroNo ratings yet

- Property Book Two of The Civil LawDocument65 pagesProperty Book Two of The Civil LawDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- BCBSC's Answers To Plaintiff's Interrogatories 012218Document6 pagesBCBSC's Answers To Plaintiff's Interrogatories 012218FOX45No ratings yet

- MY REVIEWER Remedial LawDocument113 pagesMY REVIEWER Remedial LawDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

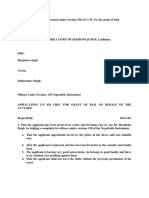

- Application Under Section 436 of CR PC For The Grant of BailDocument3 pagesApplication Under Section 436 of CR PC For The Grant of Bailpooja100% (1)

- People v. VillacortaDocument1 pagePeople v. VillacortaJemson Ivan WalcienNo ratings yet

- Case Digest in Consti Rev. Prepared by Francisco Arzadon Use at Own Risk (2018)Document52 pagesCase Digest in Consti Rev. Prepared by Francisco Arzadon Use at Own Risk (2018)Patrick TanNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law Bar 2014Document21 pagesCommercial Law Bar 2014Dodong Lamela100% (1)

- The UK ConstitutionDocument43 pagesThe UK ConstitutionSafitNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesDocument14 pagesDoctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesEmmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciNo ratings yet

- People V EvangelistaDocument2 pagesPeople V EvangelistaRomarie AbrazaldoNo ratings yet

- SpecCiv Declaratory-Relief BaeNotesSeriesDocument1 pageSpecCiv Declaratory-Relief BaeNotesSeriesMark DungoNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure GF CASESDocument7 pagesSearch and Seizure GF CASESAnonymous GMUQYq8No ratings yet

- He Rules On Administrative Investigation by The Sangguniang BayanDocument12 pagesHe Rules On Administrative Investigation by The Sangguniang BayanDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- First Amendment MemorandumDocument2 pagesFirst Amendment MemorandumPropaganda HunterNo ratings yet

- Manuel Vs AlfecheDocument2 pagesManuel Vs AlfecheGrace0% (1)

- San Miguel Vs Sandiganbayan - DigestDocument6 pagesSan Miguel Vs Sandiganbayan - DigestAnaliza Matildo0% (1)

- Maritime CommerceDocument40 pagesMaritime CommerceDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- People V AcaboDocument3 pagesPeople V AcaboKRISANTA DE GUZMANNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of Public AdministrationDocument3 pagesNature and Scope of Public AdministrationDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Marihatag Children's CodeDocument30 pagesMarihatag Children's CodeDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Review Questions On Negotiable Instruments LawDocument27 pagesReview Questions On Negotiable Instruments LawDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Rule 139-BDocument2 pagesRule 139-BChristine RelampagosNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction and Venue Riano 2 ColumnDocument30 pagesJurisdiction and Venue Riano 2 ColumnJeong100% (1)

- Case Digest Villanueva vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilDocument2 pagesCase Digest Villanueva vs. Judicial and Bar CouncilArvy AgustinNo ratings yet

- Bonsubre Jr. v. Yerro, G.R. No. 205952, February 11, 2015Document2 pagesBonsubre Jr. v. Yerro, G.R. No. 205952, February 11, 2015mae ann rodolfoNo ratings yet

- MemDocument252 pagesMemFriktNo ratings yet

- CJ Sereno On Plagiarism Against Justice Del CastilloDocument50 pagesCJ Sereno On Plagiarism Against Justice Del CastilloSophiaKirs10100% (1)

- People Vs Villanueva Legal EthicsDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Villanueva Legal EthicsDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Section 7-11Document6 pagesSection 7-11Kyla100% (1)

- Proposal - Legal ResearchDocument4 pagesProposal - Legal ResearchNeva Bersamen BenitoNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Case DigestDocument61 pagesCivil Law Case DigestKristine N.No ratings yet

- Amendment Revision Codification Repeal PDFDocument9 pagesAmendment Revision Codification Repeal PDFGJ LaderaNo ratings yet

- Ivler Vs San PedroDocument2 pagesIvler Vs San PedroMacNo ratings yet

- People v. Mallari (GR No L-58886, Dec 13, 1998)Document1 pagePeople v. Mallari (GR No L-58886, Dec 13, 1998)d100% (1)

- Pryce Corporation vs. PAGCORDocument3 pagesPryce Corporation vs. PAGCORJulieNo ratings yet

- Digest - People v. OritaDocument3 pagesDigest - People v. OritaDae Joseco100% (1)

- RTC Court VisitDocument3 pagesRTC Court VisitRanin, Manilac Melissa SNo ratings yet

- Gitlow v. New York BriefDocument2 pagesGitlow v. New York BrieftannerjsandsNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez V FranciscoDocument3 pagesRodriguez V FranciscoReyar SenoNo ratings yet

- People Vs NazarenoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs NazarenoCheza Biliran100% (1)

- Parada v. Veneracion DigestDocument1 pageParada v. Veneracion DigestFrancis GuinooNo ratings yet

- LegalEthics - OCA vs. JudgeYuDocument3 pagesLegalEthics - OCA vs. JudgeYuSherry Jane GaspayNo ratings yet

- K&G Mining Corporation vs. Acoje Mining Company, Incorporated, Et Al. G.R. No. 188364, February 11, 2015, Third Division, ReyesDocument1 pageK&G Mining Corporation vs. Acoje Mining Company, Incorporated, Et Al. G.R. No. 188364, February 11, 2015, Third Division, ReyesLDNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs VS: Second DivisionDocument11 pagesPetitioner Vs VS: Second DivisionShawn LeeNo ratings yet

- Lansang vs. GarciaDocument29 pagesLansang vs. GarciaKanshimNo ratings yet

- PD 532 - Anti-Piracy and Anti-Highway Robbery Law of 1974Document2 pagesPD 532 - Anti-Piracy and Anti-Highway Robbery Law of 1974Kyle GwapoNo ratings yet

- People v. TogononDocument4 pagesPeople v. TogononJoy NavalesNo ratings yet

- Francisco Vs CA Prescription DigestDocument2 pagesFrancisco Vs CA Prescription DigestMar Jan GuyNo ratings yet

- Dantes v. CaguiaDocument6 pagesDantes v. Caguiaida_chua8023No ratings yet

- Leonen V DigestDocument4 pagesLeonen V DigestBfp Siniloan FS LagunaNo ratings yet

- Legal EthicsDocument5 pagesLegal EthicsDrewz BarNo ratings yet

- Exceptions To Rule On Final and Executory JudgmentsDocument7 pagesExceptions To Rule On Final and Executory JudgmentsFrancesco Celestial BritanicoNo ratings yet

- 15Document2 pages15NympsandCo PageNo ratings yet

- 24p Khalid Asaad Hashim Al-TumaDocument30 pages24p Khalid Asaad Hashim Al-TumaEncik Mimpi0% (1)

- Freedom of Speech, Press, ExpressionDocument21 pagesFreedom of Speech, Press, ExpressionthedoodlbotNo ratings yet

- PRIMA PARTOSA-JO, Petitioner, vs. THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and HO HANGDocument32 pagesPRIMA PARTOSA-JO, Petitioner, vs. THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and HO HANGJen Agustin MalamugNo ratings yet

- People VS JuguetaDocument2 pagesPeople VS JuguetaMa. Goretti Jica Gula100% (1)

- Gonzalez v. KatigbakDocument2 pagesGonzalez v. KatigbakRon AceNo ratings yet

- Minor Francisco Juan Larranaga vs. CADocument1 pageMinor Francisco Juan Larranaga vs. CAJohn AmbasNo ratings yet

- People V Tibon G.R. No. 188320 Parricide CaseDocument12 pagesPeople V Tibon G.R. No. 188320 Parricide CaseOnireblabas Yor OsicranNo ratings yet

- People vs. Andan (Case)Document16 pagesPeople vs. Andan (Case)jomar icoNo ratings yet

- Calilap Vs DBPDocument1 pageCalilap Vs DBPPaula GasparNo ratings yet

- People Vs OlivaDocument1 pagePeople Vs OlivaFVNo ratings yet

- Avengoza Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesAvengoza Vs PeopleJonathan RiveraNo ratings yet

- Noelito Dela CruzDocument2 pagesNoelito Dela CruzGrey Gap TVNo ratings yet

- Tenoso Vs EchanezDocument4 pagesTenoso Vs EchanezRenzy CapadosaNo ratings yet

- Forensics Cases IIDocument82 pagesForensics Cases IIGlyza Kaye Zorilla PatiagNo ratings yet

- Exam NotesDocument53 pagesExam NotesDev AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Proportionality-What Simpler Means Could Have Been Taken?Document6 pagesProportionality-What Simpler Means Could Have Been Taken?Aditya SinghNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 FREEDOM OF EXPRESSIONDocument17 pagesChapter 13 FREEDOM OF EXPRESSIONRacheal SantosNo ratings yet

- Case BriefDocument4 pagesCase Briefnaveed37370No ratings yet

- Key Case: Schenck v. United States (1919) : 1. Clear and Present Danger TestDocument6 pagesKey Case: Schenck v. United States (1919) : 1. Clear and Present Danger TestSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Dennis v. United States Brandenburg v. Ohio Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire Gooding v. Wilson R.A.V. v. St. PaulDocument4 pagesDennis v. United States Brandenburg v. Ohio Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire Gooding v. Wilson R.A.V. v. St. PaulHeechul ParkNo ratings yet

- Philippine Blooming Mills Employment Organization VsDocument2 pagesPhilippine Blooming Mills Employment Organization VsFrancesco Celestial BritanicoNo ratings yet

- Issue and Held CabansagDocument2 pagesIssue and Held CabansagRuth DulatasNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For Reading in Philippine HistoryDocument16 pagesSyllabus For Reading in Philippine HistoryDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Ntroduction To Ublic Dministration: Instructor: Office HoursDocument10 pagesNtroduction To Ublic Dministration: Instructor: Office HoursDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- GE RPH New NormalDocument21 pagesGE RPH New NormalDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Sample Module - .StrategicmgtDocument8 pagesSample Module - .StrategicmgtDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Tfijni I (Document31 pagesTfijni I (Roy Luigi BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Refreshers Activity in Labor Law (Activity 2)Document4 pagesRefreshers Activity in Labor Law (Activity 2)Dodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Authors: All SB MembersDocument6 pagesAuthors: All SB MembersDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- The Foundation of International Human Rights LawDocument1 pageThe Foundation of International Human Rights LawDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- SuccessionDocument91 pagesSuccessionDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Recit and Quiz ConofLawsDocument1 pageRecit and Quiz ConofLawsDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Persons Family RelationsDocument64 pagesPersons Family RelationsDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Changes in Insurance Code: by Chapter and TitleDocument4 pagesChanges in Insurance Code: by Chapter and TitleDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- Blank 9Document4 pagesBlank 9grace caubangNo ratings yet

- New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262 (1932)Document32 pagesNew State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262 (1932)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Illinois Computer Research, LLC v. Google Inc. - Document No. 128Document7 pagesIllinois Computer Research, LLC v. Google Inc. - Document No. 128Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Banko Filipino vs. DiazDocument16 pagesBanko Filipino vs. DiazSherwin Anoba CabutijaNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. Joseph A. Dirienzo, Appellant, V. Howard D. Yeager, Principal Keeper of The New Jersey State Prison at TrentonDocument6 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. Joseph A. Dirienzo, Appellant, V. Howard D. Yeager, Principal Keeper of The New Jersey State Prison at TrentonScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chronology of Important EventsDocument13 pagesChronology of Important EventsAiceeNo ratings yet

- Angelina Francisco vs. NLRC, Kasei Corporation Et. Al.Document7 pagesAngelina Francisco vs. NLRC, Kasei Corporation Et. Al.talla aldoverNo ratings yet

- Amigable vs. Cuenca G.R. No. L-26400 43 SCRA 487 February 29, 1972Document2 pagesAmigable vs. Cuenca G.R. No. L-26400 43 SCRA 487 February 29, 1972senpai FATKiDNo ratings yet

- Amended Prayers 15 Feb 15Document8 pagesAmended Prayers 15 Feb 15Chetanya93No ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension AssignmentDocument19 pagesReading Comprehension AssignmentS162650% (2)

- NELC Witness Statement - RedactDocument8 pagesNELC Witness Statement - RedactGotnitNo ratings yet

- Cases Chattel MortgageDocument4 pagesCases Chattel MortgageDremSarmientoNo ratings yet

- Dadole v. COADocument9 pagesDadole v. COAElaine Chesca0% (1)

- CLJ 2012 4 193 LeeflDocument14 pagesCLJ 2012 4 193 LeeflAlae KieferNo ratings yet

- I) Answer The Questions According To The Following Paragraph. Choose One AlternativeDocument5 pagesI) Answer The Questions According To The Following Paragraph. Choose One AlternativeJaviera Chandia RamirezNo ratings yet

- Art 7 Executive TranscriptDocument19 pagesArt 7 Executive TranscriptLove Jirah JamandreNo ratings yet

- People V GambaDocument5 pagesPeople V Gambaarianna0624No ratings yet

- Termination of The Contract and Wrongful Dismissal-1Document21 pagesTermination of The Contract and Wrongful Dismissal-1KTThoNo ratings yet

- Warden Petition For Review To The Arizona Supreme CourtDocument10 pagesWarden Petition For Review To The Arizona Supreme CourtRoy WardenNo ratings yet

- Nevada Supreme Court Rule 49.10Document2 pagesNevada Supreme Court Rule 49.10acie600No ratings yet

- Laygo vs. Solano MayorDocument7 pagesLaygo vs. Solano MayorMerNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Allen University, An Educational Corporation Chartered by The State of South Carolina, Debtor, 497 F.2d 346, 4th Cir. (1974)Document3 pagesIn The Matter of Allen University, An Educational Corporation Chartered by The State of South Carolina, Debtor, 497 F.2d 346, 4th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet