Professional Documents

Culture Documents

N9. A Case Study: Alan Sillitoe's "The Fishing Boat Picture"

Uploaded by

Sunny KwonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

N9. A Case Study: Alan Sillitoe's "The Fishing Boat Picture"

Uploaded by

Sunny KwonCopyright:

Available Formats

2020/2/29 Jahn: PPP/Narratology

mind style The textual evocation, especially by typical diction, rhetoric, and syntax, of a

narrator's or a character's mindset and typical patterns of thinking. See Fowler (1977:

76); Leech and Short (1981: ch. 6); Nischik (1991).

"Corto y derecho," he thought, furling the muleta. Short and straight. Corto y derecho.

(Hemingway, "The Undefeated" 201) [A bullfighter thinking in bullfighting terms.]

Ah, to be all things to all people: children, husband, employer, friends! It can be done:

yes, it can: super woman. (Weldon, "Weekend" 312) [The weary exclamation, the

enumeration of stress factors, and the ironical allusion are typical features of Martha's

mind style.]

N8.13. Following Hough (1970), the term coloring is occasionally used to refer to the local

coloring (also 'tainting' or 'contamination') of the narrator's style by a character's diction,

dialect, sociolect, or idiolect, often serving a comic or ironical purpose. Colouring is most

functional when the narrator's and the character's voices are equally distinctive (typically, in the

fiction of Austen, James, Lawrence, and Mansfield). Hough 1970; Page 1973: ch. 2; McHale

1978: 260-262; Stanzel 1984: 168-184; Fludernik 1993: 334-338. Example:

Uncle Charles repaired to the outhouse (Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist) [The original

example used by Kenner (1978: ch. 2) to illustrate what he termed the 'Uncle Charles

Principle'. The word "repaired" is typical of the character's diction.]

Ol Abe always felt relaxed and great in his Cadillac and today he felt betteranever (Selby,

Last Exit to Brooklyn) [a diegetic statement appropriating the character's "betteranever"].

N9. A Case Study: Alan Sillitoe's "The Fishing Boat Picture"

(In the following, all page number references are to the reprint of Sillitoe's story in The Penguin

Book of Modern British Short Stories, ed. Malcolm Bradbury, London: Penguin, 1988, 135-149.

The story was originally published in 1959.)

N9.1. Like many first-person narratives, Sillitoe's "Fishing-Boat Picture" is a fictional

autobiography. Harry is a mature narrator who looks back on his past life. Although he is only

fifty-two at the time of writing the story, he feels his life is all but over. Like many first-person

narrators, he has become not only older but also wiser. Looking back on his life, he realizes that

he made many mistakes, especially in his behavior towards his wife Kathy. The story's first-

person narrative situation is uniquely suited for presenting Harry's insights about his wasted life.

N9.2. The story is told in a straightforwardly chronological manner, and its timeline can be

established quite accurately (cp N4.8). The story's action begins with Harry's and Kathy's "walk

up Snakey Wood" (135). Kathy leaves Harry after six years, when he is thirty (136); so, at the

beginning he must be twenty-four. Since "it's [...] twenty-eight years since I got married" (135),

the narrating I's current age must be fifty-two. Kathy's weekly visits begin after a ten-year

interval (139), when Harry is forty. Kathy's visits continue for six years (147), and when she

dies, terminating the primary story line, the experiencing I is forty-six. A number of historical

allusions indicate that Harry's and Kathy's final six years are co-extensive with World War II

(140, 147). The narrative act itself takes place in 1951, six years after Kathy's death .

N9.3. The story's action episodes focus on Kathy, picking out their first sexual encounter, the

violent quarrel that makes her run away, her return ten years later, her ensuing weekly visits,

the repeated pawnings of the fishing-boat picture, and her death and funeral. Throughout their

relationship, Harry "doesn't get ruffled at anything" (136), and he remains unemotional and

indifferent to the point of lethargy. To the younger Harry, marriage means "only that I changed

one house and one mother for a different house and a different mother" (136). Although he

never sets foot from Nottingham (139), his main idea of a good time is reading books about far-

away countries like India (137) and Brazil (139). He cannot even cry at Kathy's funeral ("No

such luck", 148). And yet, her ignoble death -- in a state of drunkenness she is run over by a

lorry -- causes a change in him. Now he cannot forget her as he did after she left him (139-

140); the only thing he can do is obsessively review the mistakes he has made. In the final

retrospective epiphany, he realizes three things with devastating clarity: that he loved Kathy but

never showed it, that he was insensitive to her need for emotional involvement and

communication, and that her death robbed him of a purpose in life.

N9.4. The theme of becoming aware of one's own flaws can be treated well in a first-person

narrative situation. Unlike the ordinary well-spoken authorial narrator, who cannot himself be

present as a character in the story, Harry's working-class voice and diction is a functional and

characteristic feature in Sillitoe's story. His self-consciousness in telling the story ("I'd rather not

make what I'm going to write look foolish by using dictionary words", 135) and his involvement

in the story support the theme of developing self-recognition. Whereas Harry's story is an

http://www.uni-koeln.de/~ame02/pppn.htm#N10 64/76

You might also like

- Catch As Catch Can: The Collected Stories and Other WritingsFrom EverandCatch As Catch Can: The Collected Stories and Other WritingsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (36)

- Liber KariDocument16 pagesLiber KariAldo CokaNo ratings yet

- SAR Vs HopscotchDocument7 pagesSAR Vs HopscotchtityperezNo ratings yet

- Humor - A Friend in the Library: Volume VI - A Practical Guide to the Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes - In Twelve VolumesFrom EverandHumor - A Friend in the Library: Volume VI - A Practical Guide to the Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes - In Twelve VolumesNo ratings yet

- Novel Summary 1Document4 pagesNovel Summary 1am_mailNo ratings yet

- Lodge David The Lives of Graham GreeneDocument31 pagesLodge David The Lives of Graham GreeneΝΤσιώτσοςNo ratings yet

- In the Shadow of King Saul: Essays on Silence and SongFrom EverandIn the Shadow of King Saul: Essays on Silence and SongRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- J D SalingerDocument10 pagesJ D SalingerBenjamin J. IrishNo ratings yet

- Literary Terms 1Document6 pagesLiterary Terms 1ChemistryHonorsNo ratings yet

- Ernest HemingwayDocument6 pagesErnest HemingwayRoxana ȘtefanNo ratings yet

- A Farewell To Arms by Ernest Hemmingway, and Lord of The Flies by William Golding, AreDocument5 pagesA Farewell To Arms by Ernest Hemmingway, and Lord of The Flies by William Golding, ArebmfgeorginNo ratings yet

- Huckleberry Finn AnalysisDocument5 pagesHuckleberry Finn AnalysisGiovanna CostantinoNo ratings yet

- CC 5 ExamDocument4 pagesCC 5 Examsagnik thakurNo ratings yet

- Victory: "A caricature is putting the face of a joke on the body of a truth."From EverandVictory: "A caricature is putting the face of a joke on the body of a truth."No ratings yet

- Harold Bloom, Albert A. Berg-George Orwell's 1984 (Bloom's Guides) (2004)Document125 pagesHarold Bloom, Albert A. Berg-George Orwell's 1984 (Bloom's Guides) (2004)zdanakas100% (1)

- Realistic Vs Romantic: The Imagistic World of Post-War English LiteratureDocument25 pagesRealistic Vs Romantic: The Imagistic World of Post-War English LiteratureShahpar AltafNo ratings yet

- The Tragic Conservatism of Ernest Hemingway: And Other Essays Including the Neocon CabalFrom EverandThe Tragic Conservatism of Ernest Hemingway: And Other Essays Including the Neocon CabalNo ratings yet

- MWSGDocument8 pagesMWSGapi-244470959No ratings yet

- The Misadventures of Nero Wolfe: Parodies and Pastiches Featuring the Great Detective of West 35th StreetFrom EverandThe Misadventures of Nero Wolfe: Parodies and Pastiches Featuring the Great Detective of West 35th StreetRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Hemingway's Existential Ending: Tung Chung-HsuanDocument15 pagesHemingway's Existential Ending: Tung Chung-HsuanpetrichorNo ratings yet

- The Snows of KilimanjaroDocument19 pagesThe Snows of KilimanjaroMacrina CasianaNo ratings yet

- Essay On O Henry 'A Municipal Report' PDFDocument5 pagesEssay On O Henry 'A Municipal Report' PDFFernando C.SNo ratings yet

- 7 - Chapter 2Document46 pages7 - Chapter 2bijesh babuNo ratings yet

- Waiting For Godot A Comparative Analysis FinalDocument3 pagesWaiting For Godot A Comparative Analysis FinalSimpLycheryl DemafilesNo ratings yet

- GB ShawDocument6 pagesGB ShawrohityadavalldNo ratings yet

- George Bernard Shaw HEARTBREAK HOUSE SUMMARY & ANALYSISDocument4 pagesGeorge Bernard Shaw HEARTBREAK HOUSE SUMMARY & ANALYSISBhatti KhanNo ratings yet

- Breakfast at Tifanny - S EssayDocument16 pagesBreakfast at Tifanny - S EssayAgustina BasualdoNo ratings yet

- Ernest Hemingway Book AnalysisDocument7 pagesErnest Hemingway Book AnalysisRichard DiazNo ratings yet

- Modern DramatistsDocument10 pagesModern DramatistsiramNo ratings yet

- The Legend of Sleepy HollowDocument10 pagesThe Legend of Sleepy HollowAprinfel TimaanNo ratings yet

- As Jennifer Schuessler Noted in 2009Document5 pagesAs Jennifer Schuessler Noted in 2009ÆvgeneasNo ratings yet

- Hesse's Steppenwolf: A Comic-Psychological Interpretation: Michael P. SipioraDocument25 pagesHesse's Steppenwolf: A Comic-Psychological Interpretation: Michael P. SipioraHarisonloncaricNo ratings yet

- 19th C. Lit EssayDocument10 pages19th C. Lit EssayKristína UrbanováNo ratings yet

- The Sun Also RisesDocument5 pagesThe Sun Also RiseskathrynNo ratings yet

- Seamus Heaney The Redress of PoetryDocument6 pagesSeamus Heaney The Redress of PoetryGlitterladyNo ratings yet

- Kramer 0Document8 pagesKramer 0Mariou90100% (1)

- Slaughterhouse 5Document5 pagesSlaughterhouse 5Ruxandra IoanaNo ratings yet

- Saul BellowDocument17 pagesSaul Bellowcyranobergerac2000No ratings yet

- Irving ELHDocument27 pagesIrving ELHDISHONNo ratings yet

- 3-The Victorian Period 2Document40 pages3-The Victorian Period 2marimart13No ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument21 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentPreet kotadiyaNo ratings yet

- 22.gassim DohalDocument8 pages22.gassim DohalRazak AlbagdadiNo ratings yet

- Shaw's Arms and The ManDocument12 pagesShaw's Arms and The ManMona Aly100% (1)

- Top 50 Insp. WritersDocument4 pagesTop 50 Insp. WritersNaveen KotaNo ratings yet

- Alfred Jarry, Novelist: FormDocument11 pagesAlfred Jarry, Novelist: Formjeff teh100% (1)

- The CenciDocument69 pagesThe CencifghNo ratings yet

- Gilbert and Gubar Snow White ThesisDocument6 pagesGilbert and Gubar Snow White Thesisafbtfcstf100% (2)

- Elec 1 Week 5Document15 pagesElec 1 Week 5Bryan VillarealNo ratings yet

- Hazardous Locations: C.E.C. ClassificationsDocument4 pagesHazardous Locations: C.E.C. ClassificationsThananuwat SuksaroNo ratings yet

- Ecs h61h2-m12 Motherboard ManualDocument70 pagesEcs h61h2-m12 Motherboard ManualsarokihNo ratings yet

- Standard Test Methods For Rheological Properties of Non-Newtonian Materials by Rotational (Brookfield Type) ViscometerDocument8 pagesStandard Test Methods For Rheological Properties of Non-Newtonian Materials by Rotational (Brookfield Type) ViscometerRodrigo LopezNo ratings yet

- Faa Data On B 777 PDFDocument104 pagesFaa Data On B 777 PDFGurudutt PaiNo ratings yet

- Roxas City For Revision Research 7 Q1 MELC 23 Week2Document10 pagesRoxas City For Revision Research 7 Q1 MELC 23 Week2Rachele DolleteNo ratings yet

- Random Variables Random Variables - A Random Variable Is A Process, Which When FollowedDocument2 pagesRandom Variables Random Variables - A Random Variable Is A Process, Which When FollowedsdlfNo ratings yet

- Hydraulic Mining ExcavatorDocument8 pagesHydraulic Mining Excavatorasditia_07100% (1)

- Civ Beyond Earth HotkeysDocument1 pageCiv Beyond Earth HotkeysExirtisNo ratings yet

- Gomez-Acevedo 2010 Neotropical Mutualism Between Acacia and Pseudomyrmex Phylogeny and Divergence TimesDocument16 pagesGomez-Acevedo 2010 Neotropical Mutualism Between Acacia and Pseudomyrmex Phylogeny and Divergence TimesTheChaoticFlameNo ratings yet

- Prospekt Puk U5 en Mail 1185Document8 pagesProspekt Puk U5 en Mail 1185sakthivelNo ratings yet

- Gracie Warhurst WarhurstDocument1 pageGracie Warhurst Warhurstapi-439916871No ratings yet

- T5 B11 Victor Manuel Lopez-Flores FDR - FBI 302s Re VA ID Cards For Hanjour and Almihdhar 195Document11 pagesT5 B11 Victor Manuel Lopez-Flores FDR - FBI 302s Re VA ID Cards For Hanjour and Almihdhar 1959/11 Document Archive100% (2)

- Top Activist Stories - 5 - A Review of Financial Activism by Geneva PartnersDocument8 pagesTop Activist Stories - 5 - A Review of Financial Activism by Geneva PartnersBassignotNo ratings yet

- EN 50122-1 January 2011 Corrientes RetornoDocument81 pagesEN 50122-1 January 2011 Corrientes RetornoConrad Ziebold VanakenNo ratings yet

- Iaea Tecdoc 1092Document287 pagesIaea Tecdoc 1092Andres AracenaNo ratings yet

- ALE Manual For LaserScope Arc Lamp Power SupplyDocument34 pagesALE Manual For LaserScope Arc Lamp Power SupplyKen DizzeruNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document6 pagesChapter 1Grandmaster MeowNo ratings yet

- 2016 W-2 Gross Wages CityDocument16 pages2016 W-2 Gross Wages CityportsmouthheraldNo ratings yet

- Network Fundamentas ITEC90Document5 pagesNetwork Fundamentas ITEC90Psychopomp PomppompNo ratings yet

- Basic Econometrics Questions and AnswersDocument3 pagesBasic Econometrics Questions and AnswersRutendo TarabukuNo ratings yet

- DS Agile - Enm - C6pDocument358 pagesDS Agile - Enm - C6pABDERRAHMANE JAFNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Atomistic Simulation Through Density Functional TheoryDocument21 pagesIntroduction To Atomistic Simulation Through Density Functional TheoryTarang AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Notes On Antibodies PropertiesDocument3 pagesNotes On Antibodies PropertiesBidur Acharya100% (1)

- JFC 180BBDocument2 pagesJFC 180BBnazmulNo ratings yet

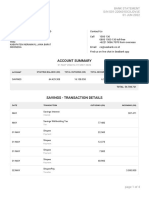

- Seabank Statement 20220726Document4 pagesSeabank Statement 20220726Alesa WahabappNo ratings yet

- Codan Rubber Modern Cars Need Modern Hoses WebDocument2 pagesCodan Rubber Modern Cars Need Modern Hoses WebYadiNo ratings yet

- Product NDC # Compare To Strength Size Form Case Pack Abcoe# Cardinal Cin # Mckesson Oe # M&Doe#Document14 pagesProduct NDC # Compare To Strength Size Form Case Pack Abcoe# Cardinal Cin # Mckesson Oe # M&Doe#Paras ShardaNo ratings yet

- Intelligent DesignDocument21 pagesIntelligent DesignDan W ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- WHO Guidelines For Drinking Water: Parameters Standard Limits As Per WHO Guidelines (MG/L)Document3 pagesWHO Guidelines For Drinking Water: Parameters Standard Limits As Per WHO Guidelines (MG/L)114912No ratings yet

- A Hybrid Genetic-Neural Architecture For Stock Indexes ForecastingDocument31 pagesA Hybrid Genetic-Neural Architecture For Stock Indexes ForecastingMaurizio IdiniNo ratings yet

- Body Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.From EverandBody Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Writing to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllFrom EverandWriting to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (83)

- Surrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSurrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates LanguageFrom EverandThe Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates LanguageRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (916)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Learn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- How Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideFrom EverandHow Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideNo ratings yet

- The Art of Writing: Four Principles for Great Writing that Everyone Needs to KnowFrom EverandThe Art of Writing: Four Principles for Great Writing that Everyone Needs to KnowRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageFrom EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (429)

- Learn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (136)

- Idioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsFrom EverandIdioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Everything You'll Ever Need: You Can Find Within YourselfFrom EverandEverything You'll Ever Need: You Can Find Within YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- Win Every Argument: The Art of Debating, Persuading, and Public SpeakingFrom EverandWin Every Argument: The Art of Debating, Persuading, and Public SpeakingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (78)

- Spanish Short Stories: Immerse Yourself in Language and Culture through Short and Easy-to-Understand TalesFrom EverandSpanish Short Stories: Immerse Yourself in Language and Culture through Short and Easy-to-Understand TalesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Messages: The Communication Skills BookFrom EverandMessages: The Communication Skills BookRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- Learn German with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: German Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn German with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: German Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (151)

- Learn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (15)