Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unit-Ii Strict Liability

Unit-Ii Strict Liability

Uploaded by

Ved BukhariyaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Unit-Ii Strict Liability

Unit-Ii Strict Liability

Uploaded by

Ved BukhariyaCopyright:

Available Formats

2.

1 STRICT LIABILITY: MEANING AND RATIONALE

Strict liability is a general term used to describe forms of liability that do not depend

upon proof of fault. Where a defendant is held responsible for unforeseeable harm or

where he is liable despite having taken all reasonable care to avoid foreseeable harm,

then liability can be said to be strict. The distinction between fault and strict liability is no

rigid. Strict duties may range from almost absolute liability, allowing virtually no

defence, to duties which amount to little more than a high standard of care in negligence.

There is no obvious unity of purpose in the areas of social conduct that are subjected to

stricter duties. If there is a discernible theme it is that people who engage in particularly

hazardous activities should bear the burden of greater risk of damage, or the risk of

greater damage, that their activities generate. Strict liability focuses on the nature of the

defendant's activity rather than, as in negligence, the way in which it is carried on, but it

should not be assumed that strict liability is synonymous with 'liability without fault'. An

activity which creates an unusual or exceptional risk may be justified by its social utility,

and therefore may be reasonable on a negligence theory, but the defendant has imposed

this risk on others for his own purpose and so his conduct is not necessarily blameless.

This idea of the allocation of the burden of the risk to the person who created it is

sometimes used as a justification for strict liability. But this usually rests on certain

unstated assumptions about causation. For example, if a housing estate is built alongside

an existing munitions factory, which created the risk of damage to the houses from an

explosion. Moreover, negligence is also concerned with risk allocation. The 'risk' of

suffering a non-negligent injury is the victim's whereas the risk of causing harm by

carelessness is the actor's. Thus analysis in terms of risk allocation does not explain why

particular kinds of risk are dealt with on the basis of fault, whereas others merit strict

liability. Appeals to the notion of extra-hazardous activities appear somewhat specious

when it is recalled that in practical terms driving a motor vehicle is one of the most risky

activities that the vast majority of the population ever undertakes, and yet it is the

paradigm of a negligence action (consider Spencer [1983) CLJ 65).

A more plausible explanation of strict liability is that it operates as a loss distribution

mechanism. Accidental damage arising from the materialization of a risk inherent in a j

particular activity is paid for by the person or enterprise carrying on the activity. That

person is in the best position to spread the loss via insurance and higher prices for the

products that the activity creates, and so the true social cost of those products is borne by J

the .consumers -in srtiall•atricitints VitaribuS' liability is a - gobd tx-ample-Of this process:

-However, fault liability can be regarded as a loss distribution mechanism too, at least in

conjunction with insurance against liability. The only difference between strict and fault

liability in this respect is the question of which losses are distributed — under fault

•

liability non-negligent damage lies where it falls, whereas under strict liability accidental

harm is distributed.

The rule of strict liability owes its origin to the case of Rylands v. Fletcher. The facts of •

this case were as follows. B, it millownei, employed independent euntmetuis, whu were

apparently competent, to construct a reservoir on his land to provide water for his mill. In

a

•

e

0

43

You might also like

- TGP Reply Brief Hitting Back at John Doe Argument in Epstein CaseDocument28 pagesTGP Reply Brief Hitting Back at John Doe Argument in Epstein CaseJim Hoft100% (1)

- Torts Rule StatementsDocument40 pagesTorts Rule Statementskoreanman100% (1)

- Law of TortDocument6 pagesLaw of TortSenelwa AnayaNo ratings yet

- Michael Danley v. Anthony Geisler - Assault With A Deadly Weapon - OCC Case No. 30-2013-00685341-CU-NP-CJC (Doc 1)Document7 pagesMichael Danley v. Anthony Geisler - Assault With A Deadly Weapon - OCC Case No. 30-2013-00685341-CU-NP-CJC (Doc 1)Fuzzy Panda100% (1)

- Summary of Indian Evidence Act (For Printout)Document274 pagesSummary of Indian Evidence Act (For Printout)Kajal Poriya100% (1)

- TORT - Question 1 (Vicarious Liability)Document17 pagesTORT - Question 1 (Vicarious Liability)Soh Choon WeeNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Vicarious LiabilityDocument4 pagesDoctrine of Vicarious LiabilitySaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- DELICT Lecture NotesDocument21 pagesDELICT Lecture Notesngozi_vinel88% (8)

- No Fault Liability and Strict LiabilityDocument8 pagesNo Fault Liability and Strict LiabilityISHAN UPADHAYANo ratings yet

- Contributory NegligenceDocument24 pagesContributory NegligenceCoolswastik0% (1)

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument6 pagesVicarious LiabilityEmmanuel Nhachi100% (3)

- Doctrines (Legal Medicine)Document6 pagesDoctrines (Legal Medicine)Billy Arupo100% (1)

- Duty of CareDocument6 pagesDuty of CareSaurabhDobriyalNo ratings yet

- Causation in Fact: But For TestDocument8 pagesCausation in Fact: But For TestPritha BhangaleNo ratings yet

- The 12 Best Happiness BooksDocument16 pagesThe 12 Best Happiness BooksVed BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- Obli CasesDocument13 pagesObli CasesLeonor LeonorNo ratings yet

- Strict Liability: A Project Report ONDocument13 pagesStrict Liability: A Project Report ONManjare Hassin RaadNo ratings yet

- Arrest Without WarrantDocument16 pagesArrest Without WarrantSoumiki GhoshNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability Master&Servant - Mod2 - Liability PDFDocument18 pagesVicarious Liability Master&Servant - Mod2 - Liability PDFBenzuiden AronNo ratings yet

- #28 - Orient Freight International v. Keihin-Everett - NaungayanDocument2 pages#28 - Orient Freight International v. Keihin-Everett - NaungayanJo NaungayanNo ratings yet

- Engineering Ethics Cases PDFDocument12 pagesEngineering Ethics Cases PDFJohn Rhey Lofranco TagalogNo ratings yet

- Roy Safety First 1952Document20 pagesRoy Safety First 1952OVVOFinancialSystems100% (2)

- 9 PMDocument5 pages9 PMricha ayengiaNo ratings yet

- 69torts Project FinalDocument24 pages69torts Project FinalSourabh AhirwarNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of The Various Arguments For and Against Vicarious LiabilityDocument7 pagesA Critical Analysis of The Various Arguments For and Against Vicarious LiabilityKartik GuptaNo ratings yet

- Responsibility, Accountability, and Liability: Studies in The Theory of Responsibility For Engineering Ethics and Engineering AccountabilityDocument95 pagesResponsibility, Accountability, and Liability: Studies in The Theory of Responsibility For Engineering Ethics and Engineering AccountabilityWAWOTOBINo ratings yet

- DELICT Lecture NotesDocument21 pagesDELICT Lecture Noteshema1633% (3)

- Vicarious Liability in The Case of Master and Servant RelationshipDocument18 pagesVicarious Liability in The Case of Master and Servant RelationshipRahul rajNo ratings yet

- Unit-Ii Strict LiabilityDocument71 pagesUnit-Ii Strict LiabilityDivyank DewanNo ratings yet

- Proportionate LiabilityDocument2 pagesProportionate LiabilityWilliam TongNo ratings yet

- Internal Assessment - 1 Subject-Law of TortsDocument6 pagesInternal Assessment - 1 Subject-Law of TortsShreyaNo ratings yet

- Types of Liabilities: Certificate Course On Liabilities Under TortDocument7 pagesTypes of Liabilities: Certificate Course On Liabilities Under TortSnehaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Business LawDocument6 pagesAssignment Business Lawrobertkarabo.jNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Law Law of Tort Week11 1Document11 pagesIntroduction To Law Law of Tort Week11 1Loo Ling LingNo ratings yet

- Torts ExamDocument38 pagesTorts Examthomaf13No ratings yet

- Unit-II Strict LiabilityDocument62 pagesUnit-II Strict LiabilityVed BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDocument21 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndianikNo ratings yet

- Activity 13.1 - LunneyDocument48 pagesActivity 13.1 - LunneyGaming SlowNo ratings yet

- Vicariousliability 160526071222Document86 pagesVicariousliability 160526071222Imad AnwarNo ratings yet

- KVJMVJHMVDocument19 pagesKVJMVJHMVShivansh PamnaniNo ratings yet

- Chanakya National Law University: PatnaDocument23 pagesChanakya National Law University: PatnaGunjan SinghNo ratings yet

- A Comparitive Study On Inevitable Accident and Act of GodDocument9 pagesA Comparitive Study On Inevitable Accident and Act of GodAkash JNo ratings yet

- RMT 551 Tort in The Construction Industry PT 2Document13 pagesRMT 551 Tort in The Construction Industry PT 2jialinnNo ratings yet

- Negligence, Strict and Absolute LiabiltyDocument19 pagesNegligence, Strict and Absolute LiabiltyNeeharika Maniar100% (1)

- ADMIN LAW ProjectDocument20 pagesADMIN LAW Projectleela naga janaki rajitha attiliNo ratings yet

- MGMT 260 CH 5 PT II SLDocument13 pagesMGMT 260 CH 5 PT II SLqhaweseithNo ratings yet

- NegligenceDocument37 pagesNegligenceTDM SNo ratings yet

- Article 2 Tile, Research Questions &objectivesDocument8 pagesArticle 2 Tile, Research Questions &objectivesNothingNo ratings yet

- HQ13 Law of Tort Sample 2018Document5 pagesHQ13 Law of Tort Sample 2018bsoc-le-05-22No ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability in TortsDocument18 pagesVicarious Liability in TortsMonu SinghNo ratings yet

- Contributory NegligenceDocument24 pagesContributory NegligenceAniket RajNo ratings yet

- Public Liability Insurance 1Document10 pagesPublic Liability Insurance 1Ayanda MabuthoNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Business Law 3rd Edition Kubasek Solutions ManualDocument13 pagesDynamic Business Law 3rd Edition Kubasek Solutions Manualdariusba1op100% (29)

- Fordham Law Review Fordham Law ReviewDocument47 pagesFordham Law Review Fordham Law ReviewJinu JoseNo ratings yet

- Notes Oblicon Arts 1262 1274Document7 pagesNotes Oblicon Arts 1262 1274Christy Tiu-FuaNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts Seminar: Vicarious LiabilityDocument7 pagesLaw of Torts Seminar: Vicarious LiabilityAddya VermaNo ratings yet

- Fundermental of law - Alice Adams - Thầy KhánhDocument29 pagesFundermental of law - Alice Adams - Thầy Khánhhomyduyen310No ratings yet

- Eleventh Edition Update Spring 24Document43 pagesEleventh Edition Update Spring 24zackmweuNo ratings yet

- Constructive Cash Distributions in A Partnership - How and When TDocument8 pagesConstructive Cash Distributions in A Partnership - How and When TAleaNo ratings yet

- Remoteness of Damage: Remote and Proximate DamageDocument9 pagesRemoteness of Damage: Remote and Proximate Damagesai kiran gudisevaNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument19 pagesVicarious LiabilityRocking MeNo ratings yet

- Contributory NegligenceDocument12 pagesContributory Negligencesai kiran gudisevaNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDocument21 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaNikhil JainNo ratings yet

- Negligence Without Fault: Trends Toward and Enterprise Liability for Insurable LossFrom EverandNegligence Without Fault: Trends Toward and Enterprise Liability for Insurable LossNo ratings yet

- Symbolism in Buddhism VedDocument18 pagesSymbolism in Buddhism VedVed BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- AvcfbfgbDocument14 pagesAvcfbfgbVed BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- Welcome To The Swiftread PDF Reader: OrangeDocument1 pageWelcome To The Swiftread PDF Reader: OrangeVed BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- The Trial of Gandhi 1922Document15 pagesThe Trial of Gandhi 1922Ved BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- CLM - ET - Sep - 2018 - Model AnswerDocument1 pageCLM - ET - Sep - 2018 - Model AnswerVed BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- 2356 2019 35 1501 27914 Judgement 04-May-2021Document190 pages2356 2019 35 1501 27914 Judgement 04-May-2021Ved BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- Unit-II Strict LiabilityDocument62 pagesUnit-II Strict LiabilityVed BukhariyaNo ratings yet

- Gonzales vs. CA (G.R. No. L-37453, May 25, 1979)Document14 pagesGonzales vs. CA (G.R. No. L-37453, May 25, 1979)Vina CagampangNo ratings yet

- VocabularyDocument2 pagesVocabularyAnnika Graniolati TockNo ratings yet

- Common Law and Civil Law Legal Systems ComparedDocument2 pagesCommon Law and Civil Law Legal Systems ComparedTame AvaaNo ratings yet

- State of Gujarat vs. DHIRUBHAI RAVATBHAI DHRANGADocument53 pagesState of Gujarat vs. DHIRUBHAI RAVATBHAI DHRANGAranjanjhallbNo ratings yet

- Sample Job Application 2022Document4 pagesSample Job Application 2022api-591849044No ratings yet

- The Police Seek To Prevent Crimes by Being Present in Places Vulnerable. C. Opportunity DenialDocument17 pagesThe Police Seek To Prevent Crimes by Being Present in Places Vulnerable. C. Opportunity DenialFelix GatuslaoNo ratings yet

- Davis, Domestic Violence-Related DeathsDocument9 pagesDavis, Domestic Violence-Related DeathsDương Vinh QuangNo ratings yet

- RFP Sample Risk AssessmentDocument7 pagesRFP Sample Risk AssessmentJean LeDucNo ratings yet

- Courtroom Etiquette, Decorum Contempt of Court - ZamreDocument68 pagesCourtroom Etiquette, Decorum Contempt of Court - ZamreJia Wei WorkNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics Corporate LawDocument8 pagesDissertation Topics Corporate LawHelpInWritingPaperSingapore100% (1)

- League of Nations PDFDocument19 pagesLeague of Nations PDFEfaz Mahamud AzadNo ratings yet

- Registry of Barangay InhabitantsDocument12 pagesRegistry of Barangay InhabitantsDenAymNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. GumbanDocument5 pagesU.S. v. GumbanleopoldodaceraiiiNo ratings yet

- EO Kasambahay Desk OfficerDocument2 pagesEO Kasambahay Desk OfficerBrgy. 10 Estancia, Pasuquin, Ilocos NorteNo ratings yet

- IPC - Project Sem IVDocument33 pagesIPC - Project Sem IVNarain SNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 The Nature of The International Legal SystemDocument12 pagesTopic 1 The Nature of The International Legal SystemevasopheaNo ratings yet

- EL BULLYING (Inglés)Document3 pagesEL BULLYING (Inglés)zoerajomontenegroNo ratings yet

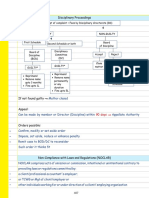

- Disciplinary Proceedings: Professional EthicsDocument3 pagesDisciplinary Proceedings: Professional EthicsDinesh MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- 20L-0993 Importance of ConstitutionDocument4 pages20L-0993 Importance of ConstitutionRafia100% (2)

- Theories of Human RightsDocument13 pagesTheories of Human RightsSalanki SharmaNo ratings yet

- SN01403Document36 pagesSN01403Szabolcs HunyadiNo ratings yet

- AI and Judicial Decision-MakingDocument18 pagesAI and Judicial Decision-MakingDeborah BACLearnNo ratings yet

- JMS Labs Vs Yusufali EesmailDocument5 pagesJMS Labs Vs Yusufali EesmailRONAK PATTANAIKNo ratings yet

- The Vulcan Insurance Co. Ltd. Vs Maharaj Singh and AnotherDocument8 pagesThe Vulcan Insurance Co. Ltd. Vs Maharaj Singh and AnotherYashasviniNo ratings yet

- Existing National Laws Related To Health Trends, Issues, and ConcernsDocument2 pagesExisting National Laws Related To Health Trends, Issues, and ConcernsHAN YTNo ratings yet