Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reaction Paper Planning Theory Juanito S Pasiliao JR

Uploaded by

JUANITO JR. PASILIAOOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reaction Paper Planning Theory Juanito S Pasiliao JR

Uploaded by

JUANITO JR. PASILIAOCopyright:

Available Formats

REACTION PAPER: PLANNING THEORY

By: Juanito S. Pasiliao Jr. EHP 210

Beginning in the twentieth century, a number of urban planning theories rose to

prominence, influencing the appearance and experience of the urban

landscape based on their popularity and duration. In the mid-twentieth century,

comprehensiveness was the major goal of city planning. As the independence of

various components of the city became more apparent, it became clear that

land use, transportation, and housing all needed to be designed in connection

to one another. Social and natural scientists, on the other hand, have become

increasingly active in planning practice, research, and teaching over the last 30

years. The demand for a single unified theory of planning has developed as their

impact has grown (Feldt, 1980-1991).

Planning is the methodical process of identifying a need and then determining

the best approach to satisfy that need, all while working within a strategic

framework that allows you to define priorities and establishes operational

standards (Shapiro, 2001). Individual and family decisions, as well as complicated

ones made by organizations and governments, are all part of the planning

process.

Urban planning is a critical instrument for achieving long-term development. It

aids in the formulation of medium- and long-term objectives that balance a

shared vision with the logical allocation of resources required to attain it. Planning

helps municipalities make the most of their budgets by guiding infrastructure and

service expenditures and combining growth demands with the need to

safeguard the environment. It also distributes economic development within a

specific area in order to achieve social goals, and it establishes a framework for

collaboration among local governments (United Nations Human Settlements

Programme (UN-Habitat), 2013).

Social systems are immensely complex and highly interrelated entities whose

entire operation is only partially understood, as experienced planners understood,

as experienced planners understand better than most individuals. A single

change in any area of such a complex system necessarily leads to a cascade of

secondary changes and adjustments across the system. The unintended

alterations are often unintended and can have unfavorable repercussions (Feldt,

1980-1991). The following theories were used in order to compress and digest the

facts and information to come up with a systematical approach with regards to

planning.

Individually, planning defined as the process of making plans for future action, is

a common human trait that manifests itself in a wide range of dreams,

computations, decisions, and acts. As a result, one of the most important

characteristics of public planning is the state-society interface and how authority

is used (Shapiro, 2001). This is one of the reasons why some theorists conflate

planning with government policy in general. However, planning theory is more

directly concerned with the role of government in environmental transformation.

It encompasses what has previously been referred to as land use planning, city

planning, urban and regional planning, town and country planning, and spatial

planning, each referring to a specific sort of planning rather than planning in

general. Because planning is concerned with the future course of action, it is

normative in nature: how planning should be done. Some planning theorists have

even ignored the study of how planning actually occurs as a field of social

investigation, believing that planning theory must promote a specific method of

planning. As a result, much of what has been written as planning theory is on

planning methods, or how to plan; yet these approaches frequently represent

broader worldviews and theoretical ideas.

Due to its action-oriented nature, theories of action are also fundamental to

planning, intersecting with technical, political, and aesthetic problems, and thus

with theories of value. Theories of action in planning can relate to knowledge

generation methodologies as well as theories and methodology for planning and

implementation. As a result, different planning theories have distinct theoretical

constitutions; (Williams, 1970) implicit theories of substance, knowledge, and

action, with varying emphasis on one or the other. The substantive focus is the

defining aspect of planning for certain theorists; for them, the substantive focus is

the defining feature of planning.

A definite subject, as well as recognized theories and methods, are required for

any branch of knowledge to expand and become distinctive. Even those who

dispute its application and relevance, planning theory is a key aspect of planning

as a study and a profession. A theoretical outlook is a fundamental aspect of any

deliberate and considered process such as planning, whether it is formally

acknowledged or implicitly embraced.

We have offered a synthesis of urban theories overviewed in Planning Theory by

Allan G. Feldt, recalling the most essential issues and questions common to most

theories of urban systems, which emphasized the need for a plurality of such

theories. The general explanation for the world’s urbanization can be found in

social organizing capacities as well as economic expansion. Even while the

process of emergence of innovations that drive the impulses is still difficult to

forecast in terms of conditions of its appearance and qualitative content, these

two processes are strongly associated over time. The spatial organization of urban

forms is beginning to be better understood, if we acknowledge that the

explanations and models that account for it must be viewed as open dynamics

rather that static equilibrium (Denise Pumain, 2019). At all levels of city

organization and systems of cities, the persistence of urban hierarchies, as well as

the scaling laws that appear between various attributes of cities, is the result of a

dynamic diffusion of innovations that exploits quantitative inequalities and

qualitative differences between cities to build complex networks of

complementarity and independencies. All citizens corporations, and municipal

governments are concerned in this regard.

References

Anderson, A. A. (2004). Theory of Change. as a tool for strategic planning.

Denise Pumain, J. R. (2019). Conclusion. Perspectives on urban theories, 14-32.

Feldt, A. G. (1980-1991). Planning Theory. 43-52.

MIASTA:, W. P. (2016). IN SEARCH OF AN IDEAL CITY. THE INFLUENCE, 1-12.

Shapiro, J. (2001). Toolkit on Overview of Planning . Civicus, 1-52.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). (2013). Urban

Planning For City Leaders. 4-12.

Williams, H. E. (1970). General Systems Theory, Systems Analysis, and. 9-33.

You might also like

- HEALEY, Patsy - in Search of Strategic in Spatial Strategic MakingDocument20 pagesHEALEY, Patsy - in Search of Strategic in Spatial Strategic MakingnNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning - Patsy HealeyDocument23 pagesStrategic Planning - Patsy HealeyRivaldiEkaMahardikaNo ratings yet

- Waiters' Training ManualDocument25 pagesWaiters' Training ManualKoustav Ghosh90% (51)

- Landman Training ManualDocument34 pagesLandman Training Manualflashanon100% (2)

- Merger Case AnalysisDocument71 pagesMerger Case Analysissrizvi2000No ratings yet

- Nursing Process & Patient Care ModalitiesDocument6 pagesNursing Process & Patient Care ModalitiesNur SanaaniNo ratings yet

- Bruce MoenDocument4 pagesBruce MoenGeorge Stefanakos100% (5)

- Breaking the Development Log Jam: New Strategies for Building Community SupportFrom EverandBreaking the Development Log Jam: New Strategies for Building Community SupportNo ratings yet

- Postpaid Bill AugDocument2 pagesPostpaid Bill Augsiva vNo ratings yet

- Make Money OnlineDocument9 pagesMake Money OnlineTimiNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Participatory PlanningDocument13 pagesThe Benefits of Participatory PlanningVanessa Williams50% (2)

- Teresita Dio Versus STDocument2 pagesTeresita Dio Versus STmwaike100% (1)

- Planning TheoryDocument26 pagesPlanning TheoryBrian GriffinNo ratings yet

- Development Plan-Part IV, 2022-2023Document3 pagesDevelopment Plan-Part IV, 2022-2023Divina bentayao100% (5)

- Planning Theories - Literature SummaryDocument25 pagesPlanning Theories - Literature SummaryKlfjqFsdafdasf100% (1)

- The Communicative Turn in Planning Theory and Its Implications For Spatial Strategy Formation (Healey 1996)Document18 pagesThe Communicative Turn in Planning Theory and Its Implications For Spatial Strategy Formation (Healey 1996)Karoline Fischer100% (1)

- Postmodern Planning TheoryDocument13 pagesPostmodern Planning Theorycaleb_butler656767% (6)

- PCC 3300 PDFDocument6 pagesPCC 3300 PDFdelangenico4No ratings yet

- The Concept of Spatial Planning and The Planning System (In The Book: Spatial Planning in Ghana, Chap 2)Document18 pagesThe Concept of Spatial Planning and The Planning System (In The Book: Spatial Planning in Ghana, Chap 2)gempita dwi utamiNo ratings yet

- Power Relationships, Citizens Participation and Persistence of Rational Paradigm in Spatial Planning: The Tuscan ExperienceDocument23 pagesPower Relationships, Citizens Participation and Persistence of Rational Paradigm in Spatial Planning: The Tuscan ExperienceSofiaVcoNo ratings yet

- Adapting The Deliberative Democracy Temp PDFDocument22 pagesAdapting The Deliberative Democracy Temp PDFGabija PaškevičiūtėNo ratings yet

- TPS 111 (Nur Khamilia)Document8 pagesTPS 111 (Nur Khamilia)Nur KhalizaNo ratings yet

- TPS 111 (Nur Khamilia)Document8 pagesTPS 111 (Nur Khamilia)Nur KhalizaNo ratings yet

- TPS 111 (Nur Khamilia)Document8 pagesTPS 111 (Nur Khamilia)Nur KhalizaNo ratings yet

- SPATIAL PLANNING SYSTEMSDocument32 pagesSPATIAL PLANNING SYSTEMSAndrei DumitruNo ratings yet

- Towards Strategic Planning Implementation For Egyptian CitiesDocument14 pagesTowards Strategic Planning Implementation For Egyptian CitiesIEREKNo ratings yet

- Towards A Philosophy of Social PlanningDocument23 pagesTowards A Philosophy of Social PlanningAdnan SahelNo ratings yet

- European Spatial Research and Policy) Top-Down and Bottom-Up Urban and Regional Planning - Towards A Framework For The Use of Planning StandardsDocument17 pagesEuropean Spatial Research and Policy) Top-Down and Bottom-Up Urban and Regional Planning - Towards A Framework For The Use of Planning Standardshasan.lubnaNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Urban DevelopmentDocument9 pagesSustainable Urban DevelopmentSara FurjamNo ratings yet

- Sanchez 20Document13 pagesSanchez 20Yasmein OkourNo ratings yet

- Towards Strategic Planning Implementation For Egyptian CitiesDocument16 pagesTowards Strategic Planning Implementation For Egyptian CitiesIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- Dinc2015 (048 061)Document14 pagesDinc2015 (048 061)Jean ClaireNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument8 pagesAnnotated BibliographyANGELICA MAE HOFILEÑANo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature on Urban Design ComponentsDocument7 pagesReview of Related Literature on Urban Design Componentsangel hofilenaNo ratings yet

- Town Planning, Planning Theory and Social Reform: International Planning Studies May 2008Document19 pagesTown Planning, Planning Theory and Social Reform: International Planning Studies May 2008rachanaNo ratings yet

- Town Planning and Social Reform: A Class PerspectiveDocument19 pagesTown Planning and Social Reform: A Class PerspectiverachanaNo ratings yet

- Reinventing Spatial Planning in A Borderless Europe: Emergent ThemesDocument15 pagesReinventing Spatial Planning in A Borderless Europe: Emergent Themesganimed1No ratings yet

- Theory and Practice in Planning - A Planners Tale FinalversionDocument7 pagesTheory and Practice in Planning - A Planners Tale Finalversionapi-256126933No ratings yet

- Community Planning: An Interdisciplinary PracticeDocument16 pagesCommunity Planning: An Interdisciplinary PracticeJosielyn ArrezaNo ratings yet

- City Planning and Polit ValuesDocument23 pagesCity Planning and Polit ValuesMichelle M. SaenzNo ratings yet

- From Old to New Policy DesignDocument21 pagesFrom Old to New Policy DesignLucasSouzaNo ratings yet

- Planning Support Systems For Spatial Planning Through Social LearningDocument2 pagesPlanning Support Systems For Spatial Planning Through Social LearningYehia Ayasha RafidhahNo ratings yet

- Zoning More Than Just A Tool Explaining Houston S Regulatory PracticeDocument18 pagesZoning More Than Just A Tool Explaining Houston S Regulatory PracticeAnonymous FDXnOdNo ratings yet

- Buitelaar Et Al - The Public Planning of Private Planning - Controlled SpontaneityDocument21 pagesBuitelaar Et Al - The Public Planning of Private Planning - Controlled SpontaneityLabdhi ShahNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Tps551Document12 pagesAssignment 1 Tps551halifeanrentapNo ratings yet

- Institutional and Stakeholder Mapping: Frameworks For Policy Analysis and Institutional ChangeDocument12 pagesInstitutional and Stakeholder Mapping: Frameworks For Policy Analysis and Institutional ChangekarimmianNo ratings yet

- Place As Layered and Segmentary Commodity. Place Branding, Smart Growth and The Creation of Product and ValueDocument17 pagesPlace As Layered and Segmentary Commodity. Place Branding, Smart Growth and The Creation of Product and ValueHadista BonitaNo ratings yet

- Innovations in Spatial Planning As A Social Process Phases Actors ConflictsDocument26 pagesInnovations in Spatial Planning As A Social Process Phases Actors ConflictsCao Giang NamNo ratings yet

- Participation International Dev EssayDocument10 pagesParticipation International Dev EssayOli NewmanNo ratings yet

- Article ReviewDocument4 pagesArticle ReviewNithya ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Planning Theory and The City PDFDocument10 pagesPlanning Theory and The City PDFophyx007No ratings yet

- Mobilities, Politics, and The Future - Critical Geographies of Green Urbanism (2017) .Document10 pagesMobilities, Politics, and The Future - Critical Geographies of Green Urbanism (2017) .Orlando LopesNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document7 pagesAssignment 1Nurul Aslah KhadriNo ratings yet

- Smartcities 02 00032 v2Document16 pagesSmartcities 02 00032 v2WondemagegnNo ratings yet

- Artículo MetodológicoDocument22 pagesArtículo MetodológicoAna_YesicaNo ratings yet

- Co Production-Key IdeasDocument12 pagesCo Production-Key Ideaskagotg12No ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document15 pagesFULLTEXT01Eb baNo ratings yet

- Relationality Territoriality Toward New Conceptualization of CitiesDocument10 pagesRelationality Territoriality Toward New Conceptualization of Citiesduwey23No ratings yet

- Howlett (2014)Document21 pagesHowlett (2014)Paulilla24No ratings yet

- University of Pretoria etd – Political Ideologies RoleDocument34 pagesUniversity of Pretoria etd – Political Ideologies RoleAbu UsamaNo ratings yet

- Development Communication Policy ScienceDocument4 pagesDevelopment Communication Policy ScienceKouame AdjepoleNo ratings yet

- Urban Planning Research PapersDocument5 pagesUrban Planning Research Papersegx124k2100% (1)

- Justification For The Research: 2.1 General Field of StudyDocument17 pagesJustification For The Research: 2.1 General Field of StudyAnonymous PjGyG6INo ratings yet

- Government-Aided Participation in Planning Singapore: Emily Y. Soh and Belinda YuenDocument14 pagesGovernment-Aided Participation in Planning Singapore: Emily Y. Soh and Belinda YuenCheng ZehanNo ratings yet

- Planning in The Face of PowerDocument15 pagesPlanning in The Face of PowertaliagcNo ratings yet

- Process of Public Policy Formulation in Developing CountriesDocument12 pagesProcess of Public Policy Formulation in Developing CountriesZakaria RahhilNo ratings yet

- RBO, Spatial Dimension of Public Administration PDFDocument17 pagesRBO, Spatial Dimension of Public Administration PDFrbocampo100% (2)

- Varieties of Civic Innovation: Deliberative, Collaborative, Network, and Narrative ApproachesFrom EverandVarieties of Civic Innovation: Deliberative, Collaborative, Network, and Narrative ApproachesNo ratings yet

- Cities as Spatial and Social NetworksFrom EverandCities as Spatial and Social NetworksXinyue YeNo ratings yet

- STPDocument32 pagesSTPvishakha_rm2000No ratings yet

- SCM Software Selection and EvaluationDocument3 pagesSCM Software Selection and EvaluationBhuwneshwar PandayNo ratings yet

- Titanium Plates and Screws For Open Wedge HtoDocument6 pagesTitanium Plates and Screws For Open Wedge HtoDaniel Quijada LucarioNo ratings yet

- SD NEGERI PASURUHAN PEMERINTAH KABUPATEN TEMANGGUNGDocument5 pagesSD NEGERI PASURUHAN PEMERINTAH KABUPATEN TEMANGGUNGSatria Ieea Henggar VergonantoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Professional Practices in Nepal ADocument20 pagesChapter 3 Professional Practices in Nepal Amunna smithNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Farming FPO Promotes Natural AgricultureDocument4 pagesSustainable Farming FPO Promotes Natural AgricultureSHEKHAR SUMITNo ratings yet

- You Write, It Types!: Quick Start GuideDocument21 pagesYou Write, It Types!: Quick Start Guidejean michelNo ratings yet

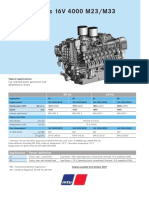

- Diesel Engines 16V 4000 M23/M33: 50 HZ 60 HZDocument2 pagesDiesel Engines 16V 4000 M23/M33: 50 HZ 60 HZAlberto100% (1)

- Australian Securities and Investments Commission V KingDocument47 pagesAustralian Securities and Investments Commission V KingCourtni HolderNo ratings yet

- Moldavian DressDocument16 pagesMoldavian DressAnastasia GavrilitaNo ratings yet

- Business ModelsDocument10 pagesBusiness ModelsPiyushNo ratings yet

- Si Eft Mandate FormDocument1 pageSi Eft Mandate FormdSolarianNo ratings yet

- Italy, Through A Gothic GlassDocument26 pagesItaly, Through A Gothic GlassPino Blasone100% (1)

- 41 Programmer Isp RT809F PDFDocument3 pages41 Programmer Isp RT809F PDFArunasalam ShanmugamNo ratings yet

- NCP GeriaDocument6 pagesNCP GeriaKeanu ArcillaNo ratings yet

- Packex IndiaDocument12 pagesPackex IndiaSam DanNo ratings yet

- Elitox PPT ENG CompressedDocument18 pagesElitox PPT ENG CompressedTom ArdiNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam Report Python code Fibonacci sequenceDocument2 pagesMidterm Exam Report Python code Fibonacci sequenceDim DimasNo ratings yet

- Soil Penetrometer ManualDocument4 pagesSoil Penetrometer Manualtag_jNo ratings yet

- SoalDocument4 pagesSoalkurikulum man2wonosoboNo ratings yet