Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Levy The Effects of External Capital Flows On Developing Countries Financial Instability

Levy The Effects of External Capital Flows On Developing Countries Financial Instability

Uploaded by

Edgar PintoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Levy The Effects of External Capital Flows On Developing Countries Financial Instability

Levy The Effects of External Capital Flows On Developing Countries Financial Instability

Uploaded by

Edgar PintoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Effects of External Capital Flows on Developing Countries: Financial Instability or

"Wrong" Prices?

Author(s): Noemi Levy Orlik

Source: International Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 37, No. 4, Financial Flows and

Exchange Rate Movement in the Global Economy (Winter, 2008/2009), pp. 80-102

Published by: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40471098 .

Accessed: 09/01/2014 11:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

M.E. Sharpe, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal

of Political Economy.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International

JournalofPoliticalEconomy,

vol. 37, no.4, Winter

2008-9,pp. 80-102.

© 2009M.E. Sharpe,

Inc.Allrightsreserved.

ISSN 0891-1916/2009$9.50+ 0.00.

DOI 10.2753/IJP0891-19

16370404

NoemiLevy Orlik

The EffectsofExternalCapital Flows

on DevelopingCountries

FinancialInstability

or"Wrong"Prices?

Abstract:This paperdiscussestheeffectsof capitalmovement on developing

economieswhoseproduction structuresarehighlydependent on foreign technol-

ogyandimports. Itis arguedthat,insteadofincreasing

savingsandinvestment and

maximizing economicgrowth, external capitalflowsinducefinancial instability,

whichmodify "key"pricesanddepresseconomicactivity. Thisanalysisis based

on theassumption thatmoneyis endogenous andtherateofinterestis exogenous;

theexchangerateinducesinflation witha magnifiedpass-througheffect to con-

sumers,and therateof interest is a distributional

variablewhosemainobjective

is torestorefinancialgains.

Keywords:Capitalmovements, economies,

developing money(Post

endogenous

Keynesiantheory),

prices.

Formainstream theprincipal

economists, arguments explaining thebackwardness

ofdeveloping countries

havetodo withtheshallowness andnarrowness offinancial

marketsandthelackofan international

currency tofinance economicdevelopment.

Moreover, theslow economicgrowth is said to resultfromreducedsavingsas a

resultof financial

marketsegmentation and limitedexternal capitalmobility,as

wellas from"wrong"prices,becauseofgovernment intervention.

Accordingly, twopoliciesareusuallyputforth. First,thefinancial

system needs

tobe widenedanddeepenedbyincreasing thedemandforandsupplyoffinancial

instruments;inotherwords,a greater

number offirms mustissuefinancial instru-

mentsthat,inturn,moreagentsneedtodemand.Second,moneymarkets needtobe

NoemiLevyOrlikisa professor

ofeconomics,

Universidad

Nacional

AutónomadeMéxico,

Mexico;e-mail:levy@servidor.unam.mx.

Theauthor

thanksL.R Rochonas wellas an

anonymous forhelpful

referee, comments.

80

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 81

openedtointernational markets (financialglobalization)toincreasetotalsavings,1

whichifcomplemented withfreetrade,ensures"correct"pricesand maximum

efficiency.Undertheseconditionsdomesticand international "real" pricesare

supposedto equalizeso thatexternal capitalmarket equilibrium can be attained

through exchangeratemovements.

Post-Keynesians rejecttheseviews.On theone hand,J.M.Keynes's(1936)

and H. Minsky's(1987) analyses,based on theliquiditypreference theoryand

thefinancial instability

hypothesis, respectively,emphasizetheviewthatcapital

movements aredestabilizing andgenerate economiccycles.Forhorizontalists, such

as NicholasKaldorandBasil J.Moore,moneyis fullyendogenous andtherateof

is determined

interest exogenously bythecentral bank:themoneysupplyisdepicted

as a horizontalschedule- infinitelyelasticininterest-rate/money space.Circuitists

(see,amongothers, JacquesLe Bourva,MarcLavoie,andLouis-Philippe Rochon)

taketheanalysisa stepfurther byarguing thattherateofinterest is anadministered

priceandnotdetermined bymarket variable.Forthe

forces;itis a distributional

financial

latter, flowsnotrelatedtoproductive creditdestroy existing debtor,more

precisely, financialflowsunrelated to spendingon consumption and investment

destroydebt.Consequently, market

financial depthresulting,say,from globalization

can neither expandeconomicactivity norinducefinancial instability.

Whiletheseconditions applychiefly toindustrial economies,theynonetheless

arerelevant to developing economies,providedthefollowing twoconditions ap-

ply.First,thedepthoffinancial markets is nottheresultofbroadfinancial activity

(thesellingandbuyingofprivate financial instruments),butrather is causedbythe

issueof publicfinancial instruments, themainfunction of whichis to guarantee

financialmargins. Second,financial flowsdistort themainpricesoftheeconomy,

inparticular, theexchangerateandwages,whichthenmodify indirectly economic

As such,external

activity. capitalcannotautomatically expandproduction orpro-

ductivecapacity, because,in mostcases,itmerelydestroys debt.

Effluxand RefluxMechanisms

Thedemandforcreditis thestarting pointofmoneycreation andproduction.Busi-

nessesrequirecreditformeeting production costs(e.g.,wagesandoperatingcosts)

andexpansion(e.g.,thefinancing ofinvestment) - whatRochon(2005) hascalled

short-termandlong-term Thesecreditsareissuedbycommercial

credits. banksas

longas borrowers complywithcreditworthiness rulesthatmaychangeovertime.

Creditsare issuedthrough linesof creditor bankdeposits,whichare meansof

payments thathavetheabilityto settledebtsand perform of

nearlyall functions

centralbank(or base) money.

FollowingKeynes(1937), creditsare createdthrough simplebalancesheet

operationsregardless of previousresources(ex nihilo),implying therefore

that

realresources areneitherdepletednorabsorbedinthecreditcreationprocessnor

limitedbysavings.2Also,forhorizontalists, themoneysupplyis notindependent

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

ofinterest-rate movements, andcreditrationing is basedonnonprice mechanisms,

suchas normsofcreditworthiness (see Rochon2001).

For proponents of themonetary circuit,thisprocessinvolvestwo financial

flows(see RochonandRossi2004). First,private money, whichis createdthrough

creditsand deposits-andwhichenablesus to makepayments beforerevenues

arecreated(see Gnos2006)- increasesbothincomeandthemoneysupply.This

processis knownas theefflux mechanism: itis thecreation orinjection ofmoney

intotheproductive sphere.However,onceincomeis consumedorsaved(unspent

incomecreates"savings"or deposits,see Gnos 2006),3incomeis returned to

firms. Consumption and thepurchaseof financial assetsin thissenseare similar

acts,becausein bothcases, incomeis returned to firms. At thisstage,firmsuse

thisincometo retiretheirdebtwiththebankingsystem. Debtsarecanceledand

moneyis destroyed. Thisprocessis knownas thereflux mechanism. Ofcourse,if

households andwageearners hoardsavings,thenfirms do notsucceedincapturing

all oftheirinitialoutlays.

An interestingconclusiondrawnfromthisanalysisis thatmoneyandpricesare

unrelated.Consequently, a higherlevelofeconomicgrowth requireshigherlevels

of moneysupply,withno effecton prices,becausethemoneysupplyis related

to higherproduction or expandedproductive capacity, therebybreaking thelink

betweenmoneysupplyandprices.Inflation is largelycost-push andtheresultof

conflictoverthedistribution ofincome.

Thesecondflow(central bankmoney)results from commercial banks'interbank

deficit.Commercial banksuse centralbankmoneytosettleinterbank debtson the

booksofthecentralbank,guaranteeing thateachcommercial bankis able tobal-

ance itsbooks,evenunderconditions of unequaldistribution of depositsduring

theprocessof moneycreation(RochonandRossi 2004). It has beenarguedthat

thisconstitutes an alternativeviewtoChartalism.4

Indeed,as earlyas thelate1950s,Le Bourva(1992) arguedthatthemoneysupply

is a dependent variable.Centralbankstherefore cannotmodify theamount ofliquid-

itythrough changesin themonetary base. Rather, a centralbankaccommodates

all commercial banks'demandforreserves. As such,thebenchmark interest rate

is themainmonetary policyinstrument, determined bythemonetary authorities,

thereby reversing thecausalityputforward byproponents ofthequantity theory of

money(Lavoie 1992).The relevant causalitygoes fromthedemandforcredit,to

thesupplyofcreditandthecreation ofmoney(moneysupply),higher income,and

finallytothedemandforandsubsequent supplyofcentralbankmoney(reserves).

As a result,themoneymultiplier is a fallacy.5

Fromtheabovearguments, horizontal istsandcircuitists highlight twoimpor-

tantissues.First,thecentralbankis forcedto satisfy (accommodate) all reserves

demandedbycommercial banksto avoidfinancial - hencethecentral

instability

banks'continuous surveillanceofthebanking system inordertomitigate financial

disturbances. Notonlyis ita lenderoflastresort, butitmustalso intervene daily.

As Rochon(1999) indicates, thiswas alreadyexplainedinA. Eichner(1987),who

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 83

calledthisthedefensive roleofthecentral bank.Second,higher liquidityis related

tohigher productionorinvestment spending. Consequently changesinproduction

or investment spendingneednotinducefinancialinstability normodifyprices,

especiallyinterestrates.

The relevant issueis thatbankcreditprecedesmoney.6 Also, therefluxto the

financial systembymeansofgoodsandservicespayments - orthrough financial

market securities

holdings- cancelsoutdebts.Indeed,all shortages ofcommercial

bankreservesareaccommodated bythecentralbank;as such,financial instabil-

ity is not theresultof notdestroying existing debts.Moreover, if liquidityrises

independently ofcreditdemand, this excess supplyof money is used toextinguish

debt.As Lavoiestates:"whenagentsdisposeofmoneybalances,thattheywishnot

to hold,theseexcessmoneybalancescan be extinguished bythereimbursement

ofpreviously accumulated debt"(2001,215).

The funding process(whichdealswithtemporal asymmetries betweeninvest-

mentdebtsandcash flowreturns) is no longera centralelementin thefinancial

system, becausecapitalmarkets are less linkedto investment finance.It nowis

accepted thatstockissuance is connected to (mergers

speculation andacquisitions)

rather thanto meettheneedsforprivateinvestment finance.

Effluxand RefluxMechanismin DevelopingEconomies

Giventheforegoing, in thissectionwe analyzethecreationand destruction of

money as it to

applies developing economies. The latter are characterized by

economicandfinancial dependencewithina contextofhighcapitalmobility and

economicglobalization (productiveand where

financial),7 internalproduction,even

fordomesticmarkets, dependson external markets.

Economicopennessthatcharacterizes developingcountriesdoes notdimin-

ishtheefflux andreflux mechanisms. Indeed,providedexternal capitalflowsare

relatedtoproduction orinvestment spending, thecentralbankissuesmoremoney

andcommercial bankdepositsincrease, leadingtohigher incomeandconsumption

levels.As a result,debtsarereimbursed (including external debts)andcentral bank

money settles domestic interbankdebts (Le Bourva 1992, 462).

The endogenousmoneytheorycontinuesto applyprovidedexternalcapital

inflowsare relatedto productionor investment spending,because debtsare

canceled.Indeed,whilenotesandcoins(centralbankliabilities)couldincrease,

liquiditywithin thebankingsystem doesnotincreasebecausesterilization occurs

automatically. In otherwords, centralbanks willtend to neutralizethese external

debts- thisis thecompensation principle,whichis madeclearbyLavoie:"because

themovements of someelementsofthecentralbankbalancesheetareautomati-

callycompensated byoppositemovements in otherelements"(2001, 216).

To date,we havenotdiscussedtheexchangerate,whichplaysa keyrolein

open(orglobalized)developing economies. According tothemainstream approach,

exchange rates should guaranteeequal real prices across economies (e.g., the

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

principle ofpurchasing powerparity[PPP],inabsoluteand,especially, inrelative

terms),which,ofcourse,is rarely, ifat all,observablein therealworld(e.g.,the

Big Mac or Starbucks indexes).A possibleexplanation is thelackof substitution

betweenimported anddomesticgoodsand services:market segmentation in the

productive sector,productdifferentiation, lengthy processesofpriceadjustment,

different productivity levelsbetweentradableand nontradable goods(especially

indeveloping countries, see Krugman andObstfeld1999,chapter14),areall pos-

siblecauses of thecollapseof PPP. M. Lavoie (2001, 219) preciselyarguesthat

althoughPPP mayholdin themediumand longrun,in theshortrunexchange

ratedevaluationscould inducehighercosts- and therefore higherprices - for

foreign goodswithout modifying effective demand,becauseinflation is followed

bysalaryincreases.

In addition,accordingto theinterest-rate parityprinciple(IPP), interest rates

acrosscountries areequalized,providedthatmarkets achieve"correct" (i.e.,equi-

librium) exchangerates.Therefore, IPP is explainedinterms ofmoneysupplyand

inflationdifferentials amongcountries. Hence,expectedexchangeratemovements

tendtoequalizeinterest rates.Again,empirical evidencecontradicts thisexplana-

tion,especiallyin developingeconomies.One reasonis thatdomesticfinancial

assetsare notperfectsubstitutes forforeignfinancialassets,and exchangerate

movements areexplainedinterms ofcapitalinflows andoutflows (seekingfinancial

gains)rather thanpricechanges.

Anotherpossibleexplanation, based on M. Kalecki'stheoryof pricedeter-

mination (see Kalecki1954a),is thepass-through effect.Accordingto thisview,

exchangeratedepreciation mainlyaffects production (domesticorforeign) based

on foreigninputs:theyincreaseinputcosts,butifthereis competition between

producers basedon domesticandforeign inputs, thelatterwillreducetheirprofit

margin so as nottoincreasepricesandthereby remaininthemarket; alternatively,

wagescan be reducedtoneutralize higherimport costs.To wit,theproblem is the

dependenceon foreigninputs.If all producers (domesticor foreign)use foreign

inputs,depreciation affects all producers alike.However,ifthereis competition

betweenthosewhousedomesticandforeign inputs,onlythelatter willbe affected,

andtheywillreducetheirprofit margin.

Regardingthefirstargument, if competition prevails,theincreasedcostsof

imports arenotfullypassedon to prices.8 According to Lavoie,"thereis a lotof

empiricalevidenceaboutthelackof a pass-through effect, whenthereis a rela-

tiveappreciation of theirowncurrency, foreignproducers lowertheirmark-ups

and absorblosses to makesurethatthepricesare in linewithlocal producers"

(2001, 219). The underlying assumption is thatgoodsand servicesareproduced

by domesticand foreignproducers thatcompetewitheach other,andexchange

ratedepreciation affects mainlyforeign producers becauseoftheirhigherimport

coefficient.Consequently, toremaininthemarket, profitsharesarereduced.More-

over,domestic producers areunaffected byexchangeratemovements becausetheir

import coefficient is low.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 85

thisargument

However, doesnotholdintheMexicaneconomy, becauseforeign

anddomestic producers haveroughly thesameimport (especiallyinthe

coefficients

dynamic sector).In thiscase,thereis nocompetition amongthemandhigher costs

arefullypassedontoprices;henceexchangeratedepreciation affectsall firms.

This

is oneexplanationofthefullpass-through effect.

afteran exchangeratedevaluation,

Moreover, wagestypically decrease(rather

thanincrease)eventhoughinflation setsin; wage reductionscan prevent prices

fromgoingup,thereby leavingunchanged margins.

profit TheEconomicCommis-

sionforLatinAmericaandtheCaribbean(ECLAC) hasarguedthat,indeveloping

wagesaredetermined

countries, bytheprevailing livingconditions oftheregion

(lowerthanindevelopedcountries) andareunrelated toproductivitychanges(see

citedinLevy2007).As such,wageswilldecrease,orincreaselessthan

C. Furtado,

prices,whentheexchangeratedepreciates.

The EffectsofExternalCapital Flowson Liquidityand Pricesin

theMexicanEconomy

To testthehypothesis outlinedabove,thissectionis dividedintothreeparts.First,

we analyzetheeffects ofexternalcapitalflowson liquidity andwe arguethatthe

monetary base remains unchanged since externalcapital inflows are relatively

unconnected to investment spending. Second, we demonstrate that theMexican

production structure has changedas a of

result globalization andFDIs, leadingto

a directcorrelation betweenexchangeratedepreciations (appreciations)andeco-

nomicstagnation (growth).Finally,we consider the relationshipbetween capital

movements andprices,particularly theeffectofexchangerateson prices,wages

andinterest rates.

Mechanism

and theCompensation

ExternalCapitalMovements

An important characteristicof LatinAmericaneconomiesis thatcapitalinflows

dramaticallyincreased in thelate 1980s,9and moreimportant, theywerehighly

disconnectedfromproduction andinvestment spending.Before the 1994Mexican

crisis,foreignportfolioinvestments (FPI) dominated externalinflowsand were

directedtoward Mexicangovernment bonds(theinfamous Tesobonos).As a result

ofNAFTAandthe1994crisis,foreign directinvestment (FDI) displacedFPI and

continued tobe unrelatedto investment spending, largelybecausetheywereused

to acquireexistingcapital(mergers - a majorcharacteristic

and acquisitions) of

globalizedtrade(see Dumenil and Levy 2005). Consequently, theneoliberalargu-

mentsforopeningup thefinancial systemdidnotoperateas promised.10

One elementthatreflects thedisconnection betweenexternalcapitalinflows

andproduction and investment spending is therelative

stabilityof themonetary

basethroughout thisperiod.Indeed,as canbe seeninFigure1, thereareincreased

levelsofinternationalreservesalongsideexternal capitalinflowsandreducednet

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

86 INTERNATIONAL

JOURNALOF POLITICAL ECONOMY

12 -

ιο-

ί" "ι

β · · *' *---

II ·

^- ^--' „ί* -

ν

-^ " - -^

Ί Λ ί /ϊ ? ι'ϋν '/îV ί * ί ί- ? ' ' ' ' '

α Α i li i i six/ i i i > s^^J i i i i 's*'^

-β

Ι ^- ·ΜΒΛ5ΟΡ - - IFVGOP I4KVGÕP I

I Un- f(MBAGOP) Un- f(MB^iOP) |

Figure1. MonetaryBase Composition in Terms of InternationalReserves

and Net InternalCredits

Source:Bancode Mexico,www.banxico.org/mx.

base; IR: international

MB: monetary reserves;NIC: Netinternal

credits

internalcredits(see Table 1). Actuallyafterthe 1994 crisis,international reserves

anchoredthe exchange rate,and net internalcreditscontinuedto be the accom-

modativevariable thatoffsetexternalflowsunconnectedto productiveactivities

(i.e., in accordance withthecompensationprinciple).

As fortherelationship betweeninternational reservesand thesterilization

mecha-

nism,itis interesting to noticetheincreasedportionof international reservesin the

centralbank's balance sheet,accountingfor72 percentof centralbank assets in

2005 (see Table 2). Also, centralbank claims on thegovernmentdisappeared,and

its claims on banks decreased significantly, withtheexceptionof the 1995-2000

period,mainlybecause of theMexican government'srescueof financialinstitutions

(particularlythebankingsector).Actually,in 2000, centralbankcreditto commer-

cial banks averaged 15 percentof centralbank totalassets (see Table 2).

The centralbank's liabilityside shows thereductionof netinternalcredits.First,

bankdepositsat thecentralbank increased,reachingin 2005 close to 30 percentof

totalcentralbank liabilities- a level not seen since the 1980s when legal reserve

requirementswere in operation.(For further discussion,see Levy and Toporowski

2007.) Second, the centralbank benefitedfromfiscal supportas governmentnet

depositsin thecentralbankreachednearly20 percentof totalliabilitiesin 2000. As

a result,thefiscaldeficit(netcentralbank claims on thegovernment)was replaced

by netgovernmentsupportto centralbanks.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 87

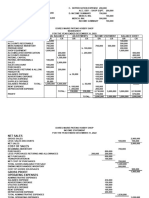

Table 1

Mean and Standard Deviation of the MonetaryBase and Its Components

International

base

Monetary reserves Netinternal

credits

1985-2005

Mean 3.8 5.8 -2.0

SD 0.2 2.3 2.5

1985-1989

Mean 4.3 5.2 -0.9

SD 0.6 3.1 3.1

1990-1995

Mean 3.6 4.5 -1.0

SD 0.2 1.4 1.5

1996-2005

Mean 3.7 6.9 -3.2

SD 0.5 1.4 1.0

Source:Bancode Mexico,www.banxico.org/mx.

deviation

SD: Standard

(ExportSector)oftheMexican

Structure

TheNewProductive

Economy

ofexternal

To analyzetheeffects capitalinflows todeter-

on prices,itis necessary

how

mine,first, dependent (or independent)thedomestic manufacturing sectoris

on external

markets,especiallyexport-orientedsectors(the dynamic ofthe

sector

economy).Only then can we betterunderstandwhether exchange ratemovements

modify economicactivity.

oftheExportSector

TheComposition

In thelastfewdecades,theratioofexportsto GDP increasedquitedramatically,

especiallyafterNAFTA(see Table3,col. 3).' ' Whatis particular

abouttheMexican

economy is thattheexport-orientedhigh-tech manufacturingsector most

increased

15

(approximately percent), easilydisplacing themining which

sector, decreased

by about20 percent, and thelow-techmanufacturing sector,whichdeclinedby

5

approximatelypercent; there were no important changes to theagricultural,

and

forestry, livestocksectors(see Table3).

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

88

pi-qr^qqcocM-i-cvip cm q

°vÇ O^ÒIÍJÒNNNÒWÒ Ó C'Í

Ο h* Ο CO CVI CM τ- I

ΙΟ

ο

ο cocoqqoqoœoœcoq ^ Ρ

™ c'i ^

ο

S β " S 8 Î5 Î5

<odòoi(C)ooioiòinò

S! 7

Ι

qqq^qi^cq^tcvicqq "^σ?

vo

o^ öcMÖiriocdr^r^öoö d oi

τ- ο co

s

o m cm

o

cm ω (pinqT-(qo)co(qw^q ^ "·"

S oJwdinoioocoiri^No cm't-1

CD

<Di-CM OJi-O^-^· CM

Û. CD CO CD CM y-

qoqqcoqh«;cqqcoo)oq q1"

'

i

W ^OÖlri^tCOÖÖÖCDCM CMCM

JŒCDCM ^ Ο) (Ο τ- T-CMCO CO

Û- CM τ- CM i-

"·" "*

δ ^°

q^iq(oqwflpqcD^^

ÖCOlOÖOOCOÖCÖ^i-1

Ο CO O CO CM

COCO

CM

1

δ

^"

o

ίβ

h-.OjqcDi^.i-^tq^tqcM

oioi^doiNcodcõ^cjJ

00 CM 00 CM i-

con.

cmcõ

CM

^

Έ

*ο

(Λ

qcMi^i-q^cMqcMqi- c'i r-^

Ο

^ ^

Έ CO g

C

?» o h»-·!- Ot-

S

h^cj)cqqcqqT- ^^ o

Ο S oScMCMÖcji^coöcodT-1 ór ö

I

û_ ^>

Ι

ο

ο Β Ι

Ι

(Ο SS

- £

õ «

„ * « s

- ο

^

?

ο

.a

g

s Ι Ι S §*I « -8

_êë Ι íígSI ! 8

(Ο

m "ce 8 2 ï S .£ » 2 §

cm 75

φ £ I Ê I I I e Ξ ? g I 11 ? g js

~ ~

< £ ü Ü J ϋ ω (3 Û.E û O to

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 89

The increasedshareof high-tech manufactured goods in totalexportscoin-

cidedwithhighlevelsofimported goods, which remained relatively

unchanged,

especiallywithrespecttoexchangeratemovements resultingfromtechnological

dependenceon foreign capitalgoodsand inputsthatmadeimportdemandprice

inelastic.

As a resultofthemanufacturing activitythatdiversified Mexicanexternal trade,

Mexicofacedlargecurrent accountdéficits becauseofitshighdependence on ex-

ternal(rather thandomestic)markets (see Table3, lastcol.). Exportsremained dis-

connected fromlocaldomesticproduction, as intheprimary sectormodel,thereby

creating export-oriented manufacturing enclaves,reminiscent ofthepreindustrial-

izationeraofthebeginning ofthetwentieth century, although nowmanufacturers

withhightechnology coexistwiththosethatprimarily use rawmaterials.

Developingcountries remained technologically dependent andunabletocom-

pete with industrialized as rate

countries; such,exchange stability continued tobe

distorted, because they need to be stable to

(overvalued) keepprices under control.

Exchangeratestability keptpricesundercontrol, yetitstillcouldnotbalancethe

externalcurrent account.Intheperiodfollowing MexicojoiningtheGATTin 1985,

thepriceinelasticity ofdemandforbothexportsandimports strengthenedandthe

incomeelasticity ofdemandincreased(see Moreno-Brid 2002).

Consequently, exchangeratedevaluations did notaffectthecomposition of

imports, as should be the case under PPP, neither in absolute and terms.

relative

Rather,it onlymodifiedits volume;thecomposition of exportsalso remained

unchanged, on

depending foreign countries' income.

Itshouldbe emphasized thatFDI continued toinfluence mostofmanufacturing

even its

activity, though production was reoriented tomeet the demandofexternal

markets. the

(During import-substitution industrializationperiod,itsatisfied

internal

demand.) More the of the

important, productivity manufacturing sectorincreased,

becauseitscapitalequipment wasnolongerbasedonobsoleteorsecond-generation

technology. Thus, there was no integration betweenthedomesticproduction sector

and industries specialized in advanced This

technology. onlyamplified internal

segmentation.

and ExchangeRateMovements

EconomicGrowth

Undertheconditionsdescribedabove,insteadof inducingeconomicgrowth, ex-

changerate tend

devaluations tohalteconomic Hence,

activity. developingecono-

miescontinuedtorequire exchangeratestotrigger

distorted economicgrowth. The

1976exchangeratedevaluation, forinstance,

(thefirst

one aftertwenty-five

years

flattened

ofexchangeratestability) economicgrowth. Nonetheless,theeconomy

recoveredrather ex-

quickly,givenhigheroil prices,whichled to an overvalued

changerateand induced one of thelasteconomic booms of the regulated of

era

theMexicaneconomy(1977-81) (see Figure2). Similarly, the 1982 exchange

was followedbya periodofeconomicstagnation,

ratedevaluation accompanied

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

90

^ο wco^coqcoinincviin^cqincqoií)

cocdcocvicvi^i-'cvicocvi-r^^cvi-r^cücsi

^y

υ. (oqwoqcoojior; ojcooot-t- cornei)

-

a>cõ^:r^is^i--ci>ior^Lo<j>c'ii^^i:if)od

<MCOC0<MCM<Mt-t-i-i- 1-1-1-1-1-

çjj

c

"c

"^ i-^i-^t^t^ÖOÖi^^t^ÖÖÖÖÖt-1

cvi^^fCD^inpcsiocqcqoqh-oqino

X T^^inododwòdiaJdciwNtíoo)

COOOCOCMCMCMCMi-T-1-τ-τ-ι-ι-ι-τ-

^ a. eq^-i-pojqcvjosjincvicvii-i-i-cvji-

áS t?c?c?d?d?d<?<f?í?<iicf<Ticf

LL cqiq^coinqcqcvjTreoi-^cqcqcvjcq

Q wwdwrpjrrwdcidciòcic)

_l

LL

<

„- o)qo)sq(Ooooooo(D(qq^cor^

χ riqeoqiqeo^qiqnejiqq^nq

g(Ο

^ u)Q^c'jcoeo^qoqq^o)^ioo)W

1

Φ

û_ ^o)LONcqNincoinc'i(oo)coco(pc'j

Q ^ r^r-'wwcow'tcoodaîdaidoONoo

ο Ο i-i-i-i-i-i-i-T-i-i-CNT-CNi-T-i-

ο

ο

ο X

œi-r-inifi^T-CONWWOffiriNCÛ

oodcoNNcodscoifliri^côcvico

LU

È

Φ

|

Ό

(β

ooooi-cvicO'iintoNooœoT-wco

00000>0)0>0>0>0)0)0>0>0>ΟΟΟΟ

,2 £ σ>σ>σ>σ>σ>θ)θ>σ>σ)σ>σ)σ>οοοο

ι- ι- ι- ι-ι- ι- ι- ι- ι- i-i- ι- OJCVlCMCVl

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

91

û.

S * a

I 8

u. S 'fi

5 li

o <u c

cocoœ^co^co^qini-oq(Noqo)q

^c&oicvi-^^-^cvicvico-^^cdoôcvid £ £ .y

'S s s

conT-tqcoojooinNooNotû^cow >>x c5

(ûincoowooiw^CNÏNcûcod^^ g Β >

^Tt^tLOlOinmcOCDCDCOCOCOCDCOCD Ο

ο. δ g

ο

όS

9 Ttooooooinco^coínincooocMco^t ^1 S S ^

S oioS^CD^loT-NOOlfllfiWOCO ví O Vj υ

^ no(û(qi-qwqqwii)cûNqo)r 3 ^ ^ ^

^ ?τττ$i i ττττττΐτ^ saisis

5 οιησ)θΝτ-οο(ο ' 15 Νί

« LJ Sntnn^òoí^t

η ο οο ν .S £ _g uî g

Ι « ?! i

2 - ε s Β--s

η ^ ο ν ^ ο σ) CO q «ο ο ν ^ ν ^ η g ^Ρ"·α g

^cdi^Locoh^<o^c'ic'icoc'ic'ico^in g "g ο S -g

8 I-SS ■§

x 'S 8*^1. "S

oco ST-cocoií)co(qqqr-N(ON S^c^1^

^^.^^,.^^^^^^^^^^

líJCO^ÒÒÒÒWCMCOCOCOCNi^^d

a g^1 g

^S^^^s

§

^

|S§IB

> <L> ζΛ *-" r- 1

^ ^oqNCDT-ojNcoiiiT-cûinNi-inN ^ο^ω^

'fiS 5Í2Õ

LL <υ ω C 3 Λ

2 η QißNcoQQWWinii) cq^tco^q ^-u'S'oow

I ej.«j.T T T o>T T T T T

cj.co« « cv, JS ïf f I

co.cNh*:1~:rN:09'^". ^^^"^^^P^P h-î | υ λ rt ^ í3

^■Nqoqoqcqcvjin^i-NincvjCDWO s^w>j°E-3

coocdco^oJcONCDQ^cvicdoœii) P° ·> 5 η 5 > *5 d

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNALOF POLITICAL ECONOMY

92 INTERNATIONAL

Figure2. The Relationship Between Exchange Rates and Economic Growth

GDP: Grossdomestic Under/over:

product; undervaluation oftheMexican

orovervaluation

exchangerate

250 ι

200 t

50 Í 'J7 l' /R

- -ER Devaluation Inflation

Figure3. Exchange Rate Movement and Inflation

by undervaluedexchange rates and high inflation.Undervalued exchange rates

induced lower domestic demand, and manufacturedgoods were channeled to

externalmarkets(exports),constitutinga displacementfrominternalto external

demand.At thebeginningof the 1990s, theMexican financialsystemwas liberal-

ized and contributedto an overvaluedexchange rate.As a result,economic growth

resumed(althoughat smallergrowthratesin comparisonto the 1978-81 period).

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 93

Figure4a. Exchange Rate and Producer Price Index (annual growthrates)

priceindex;ERI:Exchange

PPI:producer rateindex

Thetwoindexarebasedonannual rate(onemonth

growth thesamemonth

against inthe

previous basedonDecember

year), 2004andaremoving offivemonths.

average

However, the1994exchangeratedevaluation abruptlystoppedeconomicgrowth.

Whatfollowedwas one of theworstperiodsof economicstagnation in modern

timesforMexico.Considerthat,in 1995,GDP growth was actuallyminus6 per-

cent.Shortly after,as a resultofmassiveFDI inflows, theexchangeratewas once

again overvalued: economic growth quickly ensued,resultingfromlargeincreases

inexports (until2000), which was followedbyhigher pricesandlargermigrant

oil

remittances (2000-2006) (see Bleckerand Seccareccia 2007).

Fromthisdiscussion, we can see thatthereappearstobe a correlationbetween

capitalout(in)inflows and an under(over)valuedexchange rate.Capitalmovements

arethenexplainedbyoneofthefollowing American

hypotheses: economicgrowth

(thisrelationhas become weaker because of thesurgein Chineseimports), higher

exportprices(especiallyoil), U.S. interest ratemovements, whichinducelarge

FPI movements in and out of developingeconomies,foreigndirectinvestment,

andremittances. Also,thereis a correlationbetweenover(under)valued exchange

rateandeconomicgrowth(stagnation).

TheImpactofExchangeRateson Prices

theeffect

Economicopennessincreased ofexchange because

rateoncostsandprices,

external movements

capital remainan determinant

important ofexchange The

rates.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

94 INTERNATIONAL

JOURNALOF POLITICAL ECONOMY

CPI-PPI

1.8 j 0.25

gSSSSSSSSoooooooooooSoooo

Figure4b. Consumer and Producer Price Movements (annual growthrate)

CPI: consumerpriceindex;PPI: Producer

priceindex

The twoindexarebasedon anualgrowthrate(one monthagainstthesamemonthin the

previousyear),basedon December2004 andaremovingaverageoffivemonths.

Mexican centralbankadoptedthepolicyof stabilizingtheexchangerateas an inter-

mediatetargetto controlinflation.In thissection,we shall analyze theeffectof the

exchangerateon pricesand shallarguethatexchangeratedevaluationsinducehigher

costs (inputs)thatare completelypassed on to consumerprices;alternatively, these

costs can be neutralizedwithlower wages. Interestratesare set to guaranteehigh

financialcapitalreturns(externaland domestic)or to modifyincomedistribution.

The Effectsof Exchange Rates on Prices

Between 1980 and 2005, exchange rate movementswere highlycorrelatedwith

pricemovements.Whenevertheexchange ratedepreciated,inflationwould go up.

Similarly,withexchangerateovervaluations,inflation decreased(see Figure3). The

reasonis quitesimple.Withdevaluationthecostof importsincreasesand,sincethere

is no competitionbetweenforeignand domesticproducers(or substitution between

imports and domestic producedgoods), thesecosts are fullypassed on to prices.

There are two othercorrelationsthatare quite relevantto this analysis. First,

consider the effectof exchange rate movementson producerprices. If competi-

tionexists,we expect foreignproducersnot to pass the fullcosts (of imports)to

producerprices. However,the movementsof these two variables in the Mexican

economy show a different direction.In Figure 4, we can see thatexchange rate

movementsinduce higherproducer prices, reflectingweak competitionin the

Mexican economy.Hence freertrade(as a resultof thenumeroustradeagreements

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 95

00' Ç2rr/*^^' ^ Φ Ο CNJ CO l/j 1^ 00 Ο CM CO LO

■ι

1

O) ' oar oo χοο φ ο) ο ο οχ σ> o o o o o

τ- ' φ) CJ> oD p)0>CJ)OíCJ)OíCJ)0000

"2

ALCI CPI CPI-ALCI

Figure5. Consumer Prices and Average Labor Cost Movements (annual

growthrates)

ALCI: Average labor cost index. CPI: Consumer price index

The two index are based on annual growthrate (one monthagainst the same monthin the

previousyear), based on December 2004 and are five-monthmovingaverage

CO qé ι- ICOΓ^- ^'σ> y^rOF^^TvLO Qr~^/o) ι- CD i- "3"

^j €> O JO,t- c5 V^O Ο *ί ι</^ 5 $ $ 5 ^ 5

Λ_ á η m toi ν fe ο w co ^Ίλ (σ ν ο ο

£0 00~ GO to Ο) Ο) Ο) ΛΛ (7)0)0)00000

w co^t cd

-Ό.Ό ^S &jß

τ-f ^) ÇT'Jp Ο) Π) Ο) Ο) Ο) θΤ'ρ> Ο) Ο) Ο Ο Ο Ο Ο

-1-5 'Ι . . -PPI-ERI

- -CIP-PPI

_2

Figure6. The Three Pass-Through Effects

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNALOF POUTICAL ECONOMY

96 INTERNATIONAL

250-

0«3£$3S£!SS8§3

! * * ? ? ? 5 S? ? S m <3 *

-50

| ER devaluation■ ■ Interest

rates |

Figure7. Exchange Rate and InterestRate Movement

signed by Mexico), highercapital movements(FPI and even FDI) has increased

concentrationand discouragedcompetition.

The secondrelevantcorrelationtakesplace betweenmovementsofconsumerand

producerprice indexes (CPI, PPI, respectively).Again, a fullpass-througheffect

can be observed(see Figure4a). The differencebetweenCPI and PPI, on average,

is greaterthanzero, meaningthat,on average,consumerprices increasein excess

of producerprices.Nonetheless,from2003, theproducerprice index exceeds the

consumerprice index (CPI), whichcan be attributed to less inflationary

pressures

fromlower wages, as discussed in the nextsection.

Income

Exchange Rate, Prices and Workers*

The most strikingfeatureof the Mexican economy is the relationshipbetween

averagelaborcosts (ALC) and theconsumerpriceindex(CPI), whichconfirmsthe

full(or magnified)pass-througheffect.For instance,between 1982 and 2006, the

difference betweenthesetwo variableswas negative(see Figure5), implyingthat,

on average,laborcostsincreasedless thantheCPI, therebysuggestingthatreallabor

costs have been fallingthroughoutthisperiod. The biggestdifferencetook place

whenexchange rateswere undervalued(1982-87 and 1995-96). Inversely,when

the exchange rate was overvalued,prices decreased. Labor costs also decreased,

but not at the same rate; consequently,the gap between average labor costs and

pricesnarrowed.The effectof exchangeratemovementsin Mexico is symmetrical,

unliketheCanadian economy (Blecker and Seccareccia 2007).

The inverserelationshipbetween average labor costs and prices (induced by

exchangeratemovements)is a historicalfactof theLatin Americanregion,espe-

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 97

ciallyinMexico.Referring totheexchangeratedevaluation thatoccurred inChile

and Mexicoin the1950s,J.Noyola(1957) explainsthattheywerefollowedby

lowerwagelevels,especiallyincountries wheretradeunionswereundergovern-

mentcontrol(as has beenthecase in Mexico,at leastsincethe 1940s).Hence,

politicalfactors

prevented labortoretainitspurchasing power,thereby leadingto

drasticchangesinthedistribution ofincome(Pivetti1991),characterizing indeed

a counterrevolution.

The threeratios(exchangeratemovements to producerprices,producerto

consumerprices,and laborcoststo consumerprices)together givean interest-

ingoverviewof theeffects of capitalinflowson prices(see Figure6). First,the

highercostsof externalinputs(causedby exchangeratedevaluation - ERI) are

fullypassedon toproducer prices(reflectedinthePPI), indicatingthatproducers

do notsubstituteexternalinputs.Second,thereis a fullpass-through effect from

producer toconsumer prices,whichdenotesthatentrepreneurs' margins arehighly

inelasticto changinginputcosts(Mott1998). Finally,laborcostsmoveless than

consumer prices.By neutralizing higherimportcosts,inflationis controlledand

entrepreneurs'profitmargins arestabilized.Hence,highercostsarepassedon to

consumers, whilelaborcostdecreaseskeepprofit margins unchanged.

and Interest

Movement

Exchange-Rate Rates

Another strikingfeatureof theMexicaneconomyis thatexchangeratedevalua-

tionsarefollowedbyhigherinterest rates(see Figure7). Thiscan be explainedin

termsofcentral bankauthorities' decisionstosupportfinancialcapitalgains,which

needtorecoverlosses,becauseofthedepreciation ofthenationalcurrency. Hence

interestratechangesareintended tooffsetcapitalgains/losses.

Moreover, higherinterest ratesmodifythedistribution of incomein favorof

capitalowners,demandis reduced, andtheeconomy stagnates.Also,importsdecline

andthecurrent accountdeficit shrinks(oratleastdoesnotincrease).Furthermore,

economicgrowth reducescredit,without affectingcommercial bankreturns,be-

causethespreadbetweentheTreasury bondratesanddepositratescontinues tobe

extremely high,as arefeesandcommissions. Undertheseconditions, thecentral

banksetstheinterest ratein a pro-cyclicalmannerto validatefinancialgainsand

affectindirectlyeconomicactivity.

Two ProblemsAriseWhenDevelopingEconomiesGlobalize

Althoughdevelopingeconomieshave undergone structural

important changes,

oftheircommercial,

andglobalization

suchas thederegulation andpro-

financial,

ductivesectors,twomainproblemsremain.Domesticinstitutionsarenotlinked

to productive and movements

activity in

of theexchangerateremainineffective

balancingtheircurrent

account.

Regarding ofdomesticfirms

issue,theintegration

thefirst firms

to foreign re-

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

ducesdomestic spending oninvestment (see Levy2006a,2006b).Second,levelsof

creditworthiness

tendtorisebecausemoreunreliable localborrowers demandcredit

(smallandmedium domesticbusinesses thatoperate inriskier

sectorssuchas internal

markets andagricultural Third,financial

activity). margins increase,includingbank

commissions andfees,eventhough a lowervolumeofcreditis issued.Thus,invest-

mentspending ceases tobe thedeusex machinaofeconomicactivity andexports

becomethemaineconomic activity,

inducing hugeexternal incomeleakages(because

oftheincreasedlevelofimports) alongwithhighfinancial margins.

The secondobstacleforemerging countries is thatexchangeratemovements

do notbalancetheexternal currentaccount,becauseexchangeratedepreciation

induceslowerincomelevels to achievebalance-of-payment equilibrium. Ad-

exchangeratedevaluations

ditionally, are followedby higherprices(producer

andconsumer prices),lowerwages,andhigherinterest rates,thusmodifying the

distribution

ofincome.

Theneedtoattaineconomicindependence onceagainhasbecomea crucialele-

mentofdevelopment. Government intervention through fiscalpolicydeficits

aimed

atstrengthening

domestic production seemstheonlywayout,whichshouldbedone

withoutsubsidizingmultinational

corporations operating intheMexicaneconomy.

The dynamicproductive sectorsneedto be linkedto thedomesticeconomyand

shouldnotonlyrelyon low wagesin searchofan elusiveforeign demand.

Conclusion

The demandforcreditis theonlysourceof moneycreationin spiteof increased

externalcapitalmovements orgovernment openmarket External

operations. capital

inflowsrequiresterilizationif theyare unconnected to economicactivity (com-

pensation mechanism). Ifcreditdemanddoes notrise,themonetary base remains

relatively

unchanged andexternal capitalinflows lowernetinternalcredits.

Underfinancial globalization,interest ratesremainan administeredprice,the

mainobjectiveofwhichis toguarantee financialgains,whilepricestabilization

is

attainedthrough exchangeratestabilization policesandthewagebillis thebuffer

variablewhenever inflation

beginstorise.

Inflation

is determined by increasesin costsof production, whereimported

inputsareextremely relevant,as is imperfect market Undersuchcon-

structure.

marginsare protected.

ditions,profit Dependenceon theexternalsectorand the

lowcorrelation betweenexportsanddomesticproduction needsinducestructural

whichworsensas liberalization

inflation, grows.

Externalcapitalflowsin countries withhighforeign dependencealterprices,

whichthenprevent sustainedeconomicgrowth. Exchangeratedepreciation does

notinducehigher exportsnordoesitmodify thecomposition ofimports;itmerely

reducesimports, becausethereis no substitution betweenexternalanddomestic

production.Moreover, higher import costsleadtohigher consumer prices,thereby

erodingthepurchasing powerofworkers' incomeas theirrealwagesfall.Thisthen

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 99

compresses domesticmarkets; yetentrepreneur's

profit

margins remainunchanged.

inglobalizedopeneconomies.

Thisis a viciouscyclethatis moreintensified

Notes

1. Itis assumedthatexternal savingsarecomplementary andnota substitute fordomestic

savings;therefore totalsavingswouldincrease.

2. Keynesdefendsa twofoldpositionon thisissue.In TheGeneralTheory, themoney

supplyis directly relatedtointerest ratesbyputting forward theidea ofan upward-sloping

moneysupplyschedule.However, inKeynes(1937),hearguesthatanaccommodative central

bankpolicyneednotmodify ratesas commercial

interest creditexpands.

3. Keynes'sdiscussionof moneyhoardingis disregarded, a view sharedby Minsky

(1975),whomodifies thedeterminants ofmoneydemand.

4. According toChartalism, centralbankmoneyis drivenprincipally bytheneedtopay

government taxes(see Wray1998).

5. As Le Bourvasays, It theretore seemsnecessaryto abandontheconceptot money

multipliers, whicharerelicsofthequantity theory of money, andto findanother technical

explanation forthedevelopment ofbankcredit"(1992,448).

6. The speculativemotivefordemandingmoneyis notemphasizedby honzontahsts

andcircuitists.

7. Kregel(ζυυζ) arguesthateversinceLatinAmericancountries acnieveatneirinde-

pendence, theyhavebeenopeneconomieswithgovernments adaptingtheireconomiesto

theinternational divisionoflabor.

8. KholdyandSohrabian (1990) present econometric

interesting workforindustrial coun-

tries,showing thattheexchangeratepass-through onwholesalepricesandconsumer

effects

pricesneednotbe equal,arguingthatifthelatterarenotfullyaffected, theexchangerate

pass-through effectis limited.

9. StallingandStudart (2006) showthatexternal capitalflowsintermsot GDP doubled

intheearly1990sinLatinAmerica.International bankloans,bondsandequitiesrepresented

20% ofGDP in 1995,but50% in 2003. In EastAsia,external inflows increasedonlyby6

percentage points(Stallingand Studart2006,table5-6, 126),whereasGDP growth rates

between1991-2000and 2001-2003 weremuchsmallerin LatinAmericain comparison

(3.3% against7.7% and0.4% to6.8%, StallingandStudart 2006,see table5-7, 128).

10. Different theoriesarguethattheavailability ofexternal currency is one ofthemost

important requirements foreconomicgrowth. Neoliberals,suchas McKinnon(1972), and

Gurleyand Shaw (1967), advocatethatexternalopenness,includingbanksand nonbank

financial institutions,wouldincreasesavingsandinvestment. Thisviewis basedon theex

antesavingtheory, whichassumesthatexternalcapitallimitseconomicgrowth.Kalecki

(1954b),basedon different assumptions, arguesthatexternalfinancecan limiteconomic

growth, whichcan be neutralized throughincreasingexportsthatwouldfinanceeconomic

development.

11. Rodnckarguesthat therewas moreprivatization, deregulation, andtradeliberal-

izationin LatinAmericaandEasternEuropethanprobablyanywhere else at anypointin

economichistory," withMexicocertainly at theverytopofthatlist(2006,974).

References

económica(The MexicanRoad

Aspe,P. 1993.El caminomexicanode la transformation

Mexico:Fondode CulturaEconómica.

to EconomicTransformation).

P.,andW. Milberg.1993-94."DegreeofMonopoly,

Arestis, PricingandFlexibleEx-

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

100 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

changeRate."JournalofPostKeynesian Economics16,no. 2 (Winter):167-88.

Bancode México.2008.IndicadoresEconómicos(EconomieIndicators), www.banxico.

org.mx.

Bielschovsky, R. 1998."Cincuenta anosdel Pensamiento de la CEPAL: unaresena"

(Fifty YearsofThought ofCEPAL: A Critique).In Cincuentaanos del Pensamiento

de la CEPALI (Fifty YearsofThoughtofCEPAL I), ed. R. Bielschovsky, pp.9-6 1.

Santiago:CEPAL.

Blecker,R.,andM. Seccareccia.2007. "WouldGreaterNorthAmericanMonetary

Integration Protect CanadaandMexicoAgainsttheRavagesof 'DutchDisease'?"

Paperpresented attheCongressoftheLatinAmericanStudiesAssociation(LASA),

Montreal, Canada,September 6.

Chick,V.,andS. Dow. 2002. "Monetary PolicywithEndogenousMoneyandLiquidity

Preference: A NonDualisticTreatment." JournalofPostKeynesian Economics24, no.

4 (Summer):587-609.

Davidson,P. 1972.Moneyand theReal World.NewYork:JohnWileyandSons.

Dumenil,G., andD. Levy.2005. "CostsandBenefits ofNeoliberalism: A Class Analy-

sis."In Financialization and theWorldEconomy, ed. G. Epstein.Cheltenham, UK:

EdwardElgar.

Eichner, A. 1987.TheMacrodynamics ofAdvancedMarketEconomies.Armonk, NY:

M.E. Sharpe.

Epstein,G. 2005. "Introduction: Financialization andtheWorldEconomy."In Financial-

izationand theWorldEconomy, ed. G. Epstein,pp. 3-16. Cheltenham, UK: Edward

Elgar.

Gnos,C. 2006. "Accounting Identities:

MoreThanJustBookkeeping Conventions."

In Complexity, Endogenous Moneyand Macroeconomic Theory, ed. M. Setterfield,

21-35. Cheltenham, UK: EdwardElgar.

Griffith-Jones,S., andB. Stallings.1995."The NewGlobalFinanceTrends:Implications

forDevelopment." JournalofInter-American Studies& World Affairs 37, no. 3 (Fall):

59-98.

Gurley, J.G.,andE.S. Shaw.1967."FinancialStructure andEconomicDevelopment."

EconomicDevelopment and CulturalChange15 (April):257-68.

INEGI. 2008.Bancode Información Estadistica(BankofStatistical Information), www.

inegi.gob.mx/inegi/default.asp.

Kalecki,M. 1954a/1977."Costosy precios"(CostsandPrices).In EnsayosEscogidos

obredinâmicade la economiacapitalista1933-1970(SelectedEssayson theDynam-

ics oftheCapitalistEconomy1933-1970),pp. 57-76. Mexico:FCE.

. 1954b/1993. "TheProblem ofFinancing EconomicDevelopment." In Collected

Works ofMichalKalecki,vol.5, ed. M. Ostiansky, pp.23-^44.Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Keynes,J.M.1937/1973. "AlternativeTheoriesoftheRateofInterest." In TheCollected

Writings ofJohnMaynardKeynes,vol.XIV: TheGeneralTheoryandAfter, Defence

and Development, ed. D. Moggridge, pp. 201-215. London:MacmillanandCam-

bridgeUniversity Press.

. 1936/1986. La teoriageneralde la ocupación,el inter es y el dinero(The

GeneralTheoryofEmployment, InterestandMoney).Mexico:Fondode Cultura

Económica.

Koldy,S., andA. Sohrabian.1990."ExchangeRatesandPrices:EvidencefromGranger

CausalityTests."JournalofPostKeynesian Economics13,no. 1 (Fall): 71-78.

Kregel,J.2002. "Do We NeedAlternative FinancialStrategiesforDevelopment in Latin

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WINTER2008-9 101

America?"Paperpresented attheFourthSeminaron FinancialEconomics"Financial

Cooperation andInstitutions andAsymmetries in LatinAmerica,November.

Krugman, P.,andR. Baldwin.1987."The Persistence oftheU.S. TradeDeficit." Brook-

inss Paperson EconomicActivity I: 1-55.

Lavoie,M. 1992."JacquesLe Bourva'sTheoryofEndogenousCreditMoney."Reviewof

PoliticalEconomy4, no.4 (October):436-46.

. 2001. "The RefluxMechanisms andtheOpenEconomy."In Credit,Interest

Ratesand theOpenEconomy, Essayson Horizontalism, ed. L.-P.RochonandM.

Vernengo, pp. 215^2. Cheltenham, UK: EdwardElgar.

Le Bourva,J.1992."MoneyCreationsandCreditMultipliers." ReviewofPolitical

Economy 4, no. 4 (October):447-66.

Levy,N. 2006a. "El comportamiento de la inversion en economiaspequenasy abiertas

y los desafiosparala políticaeconómica:la experiência Mexicana"(The Behavior

ofInvestment in SmallOpenEconomiesandtheChallengesforEconomicPolicy:

The MexicanExperience).In Políticasmacroeconómicas para países en desarrollo

(Macroeconomic PoliciesforDevelopingCountries), ed. G. ManteyandΝ. Levy,pp.

^01-16 Mexico:Porrna.

. 2006b."El comportamiento de la inversion: revalorización de factoresmicro

y macroeconómicos en mercadosglobalizadosen la economiaMexicana"(The

Behaviorof Investment: Revaluation ofMicroandMacroeconomic FactorsinGlobal-

ized MarketsintheMexicanEconomy).In MercadosGlobalizadosen la Economia

Mexicana(GlobalizedMarketsintheMexicanEconomy),ed. G. Vargas,pp. 111-33.

Mexico:DGAPA.

. 2007. "NewEconomicGrowth Patterns in DevelopingCountries: IncreasedEx-

ternalDependenceand 'Wrong'Prices."Paperpresented at theInternationalConfer-

encein MemoryofGuyMhoneon SustainableEmployment Generation in Develop-

ingCountries: Current Constraints andAlternative Strategies,January 25-27.

Levy,N., and J.Toporowski. 2007. "Open Market in

Operations Emerging Markets:the

MexicanExperience." In OpenMarketOperations and FinancialMarkets, ed. D.

MayesandJ.Toporowski, pp. 137-177.London:Routledge.

McKinnon,R.I. 1972."El capitalen economiasfragmentadas" (Capitalin Fragmented

Economies).In Dineroy Capitalen el desarrolloeconómico(MoneyandCapitalin

EconomicDevelopment), pp. 7-26. Mexico:CEMLA.

Minsky, H. 1991. "The Endogeneity ofMoney."In NicholasKaldorand Mainstream

Economics:Confrontation or Convergence? ed. E. Nell andW. Semmler, pp.

207-220.NewYork:St. Martin'sPress.

. 1975.Las razonesde Keynes{JohnMaynardKeynes).Mexico:Fondeode Cul-

turaEconómica.

. 1986.Stabilizing an UnstableEconomy. New Haven:Yale University Press.

Moreno-Brid, J.C.2002. "Liberalización comercialy la demandade importaciones en

México"(CommercialLiberalization andDemandforImports in Mexico).Investi-

gationEconómica(EconomieInvestigation), no. 240 (April):13-50.

Moore,Β. 1988.Horizontalists and Verticalists: TheMacroeconomics ofCreditMoney.

Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Mott,T. 1998."A KaleckianViewofNew KeynesianMacroeconomics." In NewKeynes-

ian/Post Keynesian Alternatives,ed. R. Rotheim, pp. 262-71. London: Routledge.

Noyola,J.1957/1998. "Inflacióny desarrollo económicoen Chiley Mexico"(Inflation

andEconomicDevelopment inChileandMexico).In Cincuentaanos del Pensamien-

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

102 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

to de la CEPAL I (FiftyYears of ThoughtofCEPAL /), vol. 1, ed. R. Bielschovsky,pp.

273-86. Santiago: CEPAL.

Pivetti,M. 1991. Essays on Money and Distribution,London: Macmillan.

Rochon, L.-P. 1999. Credit,Money and Production:An AlternativePost-Keynesian Ap-

proach. Cheltenham,UK: Edward Elgar.

. 2001. "Horizontalism:Settingthe Record Straight."In Credit,InterestRates and

the Open Economy: Essays on Horizontalism,éd. L.-P. Rochon and M. Vernengo,pp.

31-65. Cheltenham,UK: Edward Edgar.

. 2005. "The Existence of MonetaryProfitsWithinthe MonetaryCircuit:An Es-

say in Honour of Augusto Graziani." In The MonetaryTheoryof Production: Tradition

and Perspectives,ed. G. Fontana and R. Realfonzo, pp. 125-38. London: Macmillan.

Rochon, L.-P., and S. Rossi. 2004. "Central Banking in the MonetaryCircuit."In Central

Banking in theModern World,AlternativePerspectives,ed. M. Lavoie and M. Se-

careccia, pp. 144-63. Cheltenham,UK: Edward Elgar.

Rodrick,D. 2006. "Goodbye WashingtonConsensus, Hello WashingtonConfusion?A

Review of the WorldBank's Economic Growthin the 1990s: Learningfroma Decade

of Reform."Journalof Economic Literature44, no. 4 (December): 973-87.

Salama, P. 2006. "Deudas y dependência financieradel Estado en América Latina" (Debts

and Financial Dependency of the State in Latin America). In Confrontacionesmon-

etárias: marxistasy post-keynesianosen América Latina (MonetaryConfrontations:

Marxistsand Post-Keynesians in Latin America), ed. A. Giron,pp. 101-24. Argentina:

CLACSO.

Stalling,B., and R. Studart.2006. Finance for Development: Latin American in Com-

parative Perspective.Washington,DC: Brookings InstitutionPress.

Toporowski,J. 2000. The End of Finance, Capital MarketInflation,Financial Deriva-

tivesand Pension Fund Capitalism. London: Routledge.

Wray,L.R. 1998. UnderstandingModern Money.Cheltenham,UK: Edward Elgar.

call I -800-352-2210; outsidetheUnitedStates,call 717-632-3535.

To orderreprints,

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:24:42 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Case Study On VodafoneDocument5 pagesCase Study On Vodafonesandy12leo100% (1)

- Corporation - Chapter 7Document8 pagesCorporation - Chapter 7Charles NavarroNo ratings yet

- Prof Salesmanship PQ1 - MIDTERM EXAMDocument83 pagesProf Salesmanship PQ1 - MIDTERM EXAMSherina Manlises100% (1)

- The Grand Pavilion: Panoramic ShotDocument10 pagesThe Grand Pavilion: Panoramic ShotCANASA Maria Zyra Faye T.No ratings yet

- Using Green Product Process Innovation To AchievDocument16 pagesUsing Green Product Process Innovation To AchievMostafa ElghifaryNo ratings yet

- Governance Chapter 11 Nina Mae DiazDocument3 pagesGovernance Chapter 11 Nina Mae DiazNiña Mae DiazNo ratings yet

- Video Sales Challenge Webinar NotesDocument20 pagesVideo Sales Challenge Webinar NotesGaurav MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Documents For Taftan Quetta RoadDocument125 pagesDocuments For Taftan Quetta Roadzain iqbalNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Notes PayableDocument10 pagesAccounting For Notes PayableLiza Mae MirandaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3-Common Takeover & Anti-Takeover TacticsDocument5 pagesChapter 3-Common Takeover & Anti-Takeover Tactics1954032027cucNo ratings yet

- RAYANAIR CASE STUDY1 - CompressedDocument20 pagesRAYANAIR CASE STUDY1 - Compressedyasser massryNo ratings yet

- ICO Audit Survey FeedbackDocument3 pagesICO Audit Survey FeedbackMaricris Napigkit SerranoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Analytics & Social Skills For Professional DevelopmentDocument6 pagesCognitive Analytics & Social Skills For Professional DevelopmentRishika GuptaNo ratings yet

- Accounting EndtermDocument4 pagesAccounting EndtermNow OnwooNo ratings yet

- Client Assistance ScheduleDocument9 pagesClient Assistance SchedulesefanitNo ratings yet

- Audit of ReceivablesDocument23 pagesAudit of ReceivablesBridget Zoe Lopez BatoonNo ratings yet

- 611B - ImcDocument20 pages611B - ImcRushi100% (1)

- (2014) Schivinski & Dabrowski - The Effect of Social Media Communication On Consumer Perceptions of BrandsDocument27 pages(2014) Schivinski & Dabrowski - The Effect of Social Media Communication On Consumer Perceptions of BrandsGabriela De Abreu PassosNo ratings yet

- Simu't Sarap in A CupDocument3 pagesSimu't Sarap in A CupMARY JEANELNo ratings yet

- Pinaki Panani Bogus PurchasesDocument6 pagesPinaki Panani Bogus PurchasesLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- QSP-17 SOP For Pest ControlDocument2 pagesQSP-17 SOP For Pest ControlAshish DasNo ratings yet

- Swift D'ouverture Le 06-10-2021Document4 pagesSwift D'ouverture Le 06-10-2021Jak ObNo ratings yet

- TeacherDocument28 pagesTeacherMarielle LabradoresNo ratings yet

- Biotechusa KFT Beu22006334Document1 pageBiotechusa KFT Beu22006334Brunhilda BrunhildaNo ratings yet

- Computation of ARCCDocument25 pagesComputation of ARCCgrand exploitNo ratings yet

- Print - Latest Tenders and Bids in Ethiopia From All Sources and Regions PDFDocument1 pagePrint - Latest Tenders and Bids in Ethiopia From All Sources and Regions PDFProNo ratings yet

- Internship Final ReportDocument26 pagesInternship Final ReportM06VictorNo ratings yet

- Catalist Singapore ListingDocument13 pagesCatalist Singapore ListingAmerNo ratings yet

- T1 (Introduction)Document6 pagesT1 (Introduction)Syahirah ArifNo ratings yet

- Katropa-Membership FormDocument2 pagesKatropa-Membership FormKuya Ver CastilloNo ratings yet