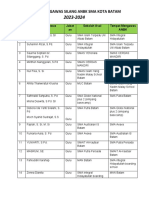

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cake or Doughnut Zizek and German Ideali

Uploaded by

danylo bozhychOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cake or Doughnut Zizek and German Ideali

Uploaded by

danylo bozhychCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Adrian Johnston, “Cake or Doughnut?: Žižek and German Idealist Emergentisms,” Žižek and

His Critics [ed. Dominik Finkelde and Todd McGowan], 2022 (forthcoming)

§1 The Philosophy Behind the Science: Revisiting an Old Debate

In the sixth and seventh chapters of my 2014 book Adventures in Transcendental

Materialism, I initiated a debate with Slavoj Žižek focused on his dialectical materialist turns to

quantum mechanics.1 Following my initial criticisms of Žižek’s speculative appeals to the

physics of the extremely small, he put forward a number of responses to me.2 In turn, I then

defended and further justified my reservations and objections on several occasions (some of

which became parts of my 2018 book A New German Idealism).3

This relatively recent debate between Žižek and me revolved around the issue of whether

quantum physics or neurobiology is the best scientific partner for the philosophical project of

forging an uncompromisingly materialist yet thoroughly anti-reductive theory of subjectivity.

Previously, I have argued against Žižek’s favoring of physics in the manner of a sympathetic

immanent critique. More precisely, I have maintained that Žižek’s privileging of quantum

mechanics is in danger of being at odds with both the anti-reductive and the materialist

commitments he and I share in common. Rooting the subject in the smallest building blocks of

the physical universe threatens to validate long-established reductive explanatory strategies vis-

1 (Adrian Johnston, Adventures in Transcendental Materialism: Dialogues with Contemporary Thinkers, Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press, 2014, pg. 139-183)

2 (Slavoj Žižek, Absolute Recoil: Towards a New Foundation of Dialectical Materialism, London: Verso, 2014, pg.

221-226)

(Slavoj Žižek, Disparities, London: Bloomsbury, 2016, pg. 38-53)

3 (Adrian Johnston, “Interview About Adventures in Transcendental Materialism: Dialogues with Contemporary

Thinkers with Graham Harman for Edinburgh University Press,” Edinburgh University Press, April 2014, http://

www.euppublishing.com)

(Adrian Johnston, “Confession of a Weak Reductionist: Responses to Some Recent Criticisms of My Materialism,”

Neuroscience and Critique: Exploring the Limits of the Neurological Turn [ed. Jan De Vos and Ed Pluth], New

York: Routledge, 2015, pg. 141-170)

(Adrian Johnston, A New German Idealism: Hegel, Žižek, and Dialectical Materialism, New York: Columbia

University Press, 2018, pg. 129-186)

à-vis human mindedness. Treating the zero-level of the physical universe as proto-subjective

threatens to run contrary to materialism (dialectical or otherwise) by lending credence to

spiritualist panpsychism. The risk is that Žižek might end up unintentionally with a both-are-

worse combination of reductionism and spiritualism—and this despite his sincere anti-reductive

and materialist inclinations.

In the past couple of years, further reflection on these matters has led me to the

conviction that there is another dimension to this disagreement between Žižek and me yet to be

addressed with adequate thoroughness. Behind the confrontation between Žižek’s dialectical

materialist rendition of quantum physics and my transcendental materialist rendition of human

biology, a confrontation in which recent and contemporary science takes center stage, there lurks

an older philosophical tension. Perhaps unsurprisingly, considering that Žižek and I both are

especially passionate about the German idealists, this tension is most manifest between the

metaphysical systems of F.W.J. Schelling and G.W.F. Hegel, particularly the philosophies of

nature put forward by these two complexly entwined contemporaries.

My present intervention aims to revisit the back-and-forth between Žižek and me apropos

interfacing empirical science with materialist philosophy in light of the divergences separating

Schelling and Hegel. In both their overarching philosophical frameworks and their more specific

Naturphilosophien, these two German idealists, so I will contend, can and should be interpreted

as emergentists avant la lettre. That is to say, they both see reality as stratified into multiple

interlinked layers, with each layer having arisen from other layers preexisting it.

However, despite both arguably being emergentists, Schelling’s and Hegel’s

emergentisms differ in certain crucial respects. First and foremost, in terms of the basic

arrangement of emergent layers, Hegel presents a layer cake model, while Schelling offers a

layer doughnut one. What do I mean by this? Hegel’s Realphilosophie gets underway with the

“mechanics” of Naturphilosophie (beginning with objectively real space and time), proceeding

within the realm of nature through “physics” (including chemistry) and then onto “organics”

(consisting of geology, botany, and zoology). Hegelian Philosophy of Nature culminates with

the sentient animal organism as itself the transitional link to the next set of emergent layers,

namely, the strata of Geistesphilosophie (grouped into the three broad headings of subjective,

objective, and absolute mind/spirit [Geist]).

In short, Hegel puts forward a layer cake model in which the bottom layer is spatio-

temporal mechanics and the top layer is artistic-religious-philosophical Geist (with many layers

in-between these two extremes). Although the highest layer allows for all the layers below it to

be comprehended in their inherent intelligibility, there is no direct meeting up and merging

together of top and bottom layers—and this despite Hegel’s fondness for circle imagery. That is

to say, various sublations (Aufhebungen) do not annul significant differences-in-kind between the

mechanical and the spiritual.

Schelling’s configuration of emergent layers, by contrast with Hegel’s, is circular such

that the lowest and the highest layers are made to converge—nay, are essentially the same single

layer. One of the biggest bones of contention between Schelling and Hegel, starting with the

latter’s barbed remark about “the night in which all cows are black” in the preface to 1807’s

Phenomenology of Spirit,4 is the former’s enthusiastic embrace of Baruch Spinoza. The young

Schelling, during the mid-1790s-to-early-1800s period in which he is developing his

4 (G.W.F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit [trans. A.V. Miller], Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977, pg. 9)

interconnected Naturphilosophie and Identiätsphilosophie, indeed relies heavily upon Spinozism,

particularly its distinction between natura naturans and natura naturata5 (a reliance persisting

well beyond the first stretch of his lengthy intellectual itinerary).6 The later Schelling, looking

back on his early Naturphilosophie in 1830, both admits this philosophy’s Spinozism as well as

5 (Baruch Spinoza, Short Treatise on God, Man, and His Well-Being, Spinoza: Complete Works [ed. Michael L.

Morgan; trans. Samuel Shirley], Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002, Chapter VIII [pg. 58], Chapter IX [pg. 58-59])

(Baruch Spinoza, Ethics, Spinoza: Complete Works, Part I, Proposition 29, Scholium [pg. 234], Part I, Proposition

31 [pg. 234], Part I, Proposition 31, Proof [pg. 235])

(Baruch Spinoza, “The Letters: Letter 9: To the learned young man Simon de Vries, from B.d.S., February 1663

(?),” Spinoza: Complete Works, pg. 782)

6 (F.W.J. Schelling, “Of the I as the Principle of Philosophy, or On the Unconditional in Human Knowledge,” The

Unconditional in Human Knowledge: Four Early Essays (1794-1796) [trans. Fritz Marti], Lewisburg: Bucknell

University Press, 1980, pg. 69)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature [trans. Errol E. Harris and Peter Heath], Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1988, pg. 15)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Presentation of My System of Philosophy, in J.G. Fichte and F.W.J. Schelling, The Philosophical

Rupture between Fichte and Schelling: Selected Texts and Correspondence [trans. and ed. Michael G. Vater and

David W. Wood], Albany: State University of New York Press, 2012, pg. 145)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Anhang zu dem Aufsatz des Herrn Eschenmayer betreffend den wahren Begriff der

Naturphilosophie, und die richtige Art ihre Probleme aufzulösen, Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik: Zweyten

Bandes, erstes Heft, Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik [ed. F.W.J. Schelling], Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1969, pg.

127)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Fernere Darstellungen aus dem System der Philosophie, Neue Zeitschrift für speculative Physik:

Ersten Bandes, erstes Stück, Neue Zeitschrift für speculative Physik [ed. F.W.J. Schelling], Hildesheim: Georg

Olms, 1969, pg. 49)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Bruno, or, On the Natural and the Divine Principle of Things [trans. Michael G. Vater], Albany:

State University of New York Press, 1984, pg. 125)

(F.W.J. Schelling, The Philosophy of Art [trans. Douglas W. Stott], Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

1989, pg. 26)

(F.W.J. Schelling, “On Construction in Philosophy” [trans. Andrew A. Davis and Alexi I. Kukeljevic], Epoché, no.

12, 2008, pg. 272-273)

(F.W.J. Schelling, System der gesammten Philosophie und der Naturphilosophie insbesondere, Ausgewählte

Schriften: Band 3, 1804-1806 [ed. Manfred Frank], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1985, pg. 261)

(F.W.J. Schelling, “System of Philosophy in General and of the Philosophy of Nature in Particular,” Idealism and the

Endgame of Theory: Three Essays by F.W.J. Schelling [trans. Thomas Pfau], Albany: State University of New York

Press, 1994, pg. 153-154, 157-159, 168, 183-184, 186)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Philosophy and Religion [trans. Klaus Ottmann], Putnam: Springer, 2010, pg. 4, 8, 14)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Aphorismen über die Naturphilosophie, Ausgewählte Schriften: Band 3, 1804-1806, pg. 693-694,

705)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Statement on the True Relationship of the Philosophy of Nature to the Revised Fichtean Doctrine:

An Elucidation of the Former [trans. Dale E. Snow], Albany: State University of New York Press, 2018, pg. 29-32)

(F.W.J. Schelling, The Ages of the World, Book One: The Past (Original Version, 1811) [trans. Joseph P. Lawrence],

Albany: State University of New York Press, 2019, pg. 105)

(F.W.J. Schelling, “Notes and Fragments to the First Book of The Ages of the World: The Past,” in Schelling, The

Ages of the World, Book One: The Past (Original Version, 1811), pg. 205, 224, 234, 238-239)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Philosophy of Revelation: The 1841-42 Berlin Lectures, Philosophy of Revelation (1841-42) and

Related Texts [trans. Klaus Ottmann], Thompson: Springer, 2020, pg. 108)

(F.W.J. Schelling, The Grounding of the Positive Philosophy [trans. Bruce Matthews], Albany: State University of

New York Press, 2007, pg. 206)

asserts that Spinozism must provide the foundation for any viable philosophical system7—with

Schelling also portraying his own treatment of human freedom as raising Spinozism to a superior

metaphysical form.8 Interestingly, Žižek, in 2020’s Hegel in a Wired Brain, elevates Spinoza to

enjoying an importance to Žižek’s own thinking comparable to that enjoyed by Immanuel Kant

and Hegel.9

That said, Schelling’s emergentism begins with the fluid “ground” (Grund) of a

primordial creative power (i.e., verb-like natura naturans) that then produces the fixed

“existence” (Existenz) of stable entities (i.e., noun-like natura naturata). According to Schelling,

human subjectivity, as the highest spiritual power, is nothing other than an irruption within the

field of existence of the ground-zero substratum underlying and generating this field. In

psychoanalytic terms, the subject is the return of repressed (Spinozistic) substance, the

resurfacing of natura naturans within the domain of natura naturata. As such, reaching the

highest Schellingian emergent layer amounts to reconnecting with the lowest one—hence a layer

doughnut model.

Tellingly, in nearly all of Žižek’s discussions of quantum mechanics, he explicitly appeals

to Schelling in particular (rather than Hegel, usually his preferred German idealist interlocutor).

The middle-period Schelling of 1809’s Freiheitschrift is Žižek’s favored reference in this vein.

What Žižek values most is this 1809 essay’s Grund-Existenz distinction. As I just implied, this

distinction amounts to a renaming of the Spinozistic contrast between natura naturans and

7 (F.W.J. Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie [ed. Walter E. Ehrhardt], Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-

Holzboog, 1989, pg. 71-72)

8 (Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 73)

9 (Slavoj Žižek, Hegel in a Wired Brain, London: Bloomsbury, 2020, pg. 2)

natura naturata. Moreover, the Freiheitschrift clearly continues to uphold what I have

characterized as the layer doughnut model.10

Žižek’s most recent major philosophical work, 2020’s Sex and the Failed Absolute,

involves him putting forward his Schellingian speculative interpretation of quantum physics

(initially developed in 1996’s The Indivisible Remainder) as the very foundation of his dialectical

materialist theoretical framework. Given both this interpretation’s reaffirmed importance for

Žižek’s philosophical apparatus as well as the previous disagreements between him and me

regarding it, I feel it to be worthwhile on this occasion to reengage critically with Žižekian

quantum metaphysics, especially as elaborated in Sex and the Failed Absolute. Such

reengagement will afford me the opportunity both to deepen philosophically the debate between

Žižek and me involving natural science as well as to bring to light the contemporary relevance of

the Schelling-Hegel pair, particularly in terms of significant contrasts between their metaphysical

edifices.

To be more precise, after delineating Schelling’s and Hegel’s early anticipations of more

recent emergentisms, I herein will argue for the Hegelian layer cake and against the Schellingian

layer doughnut emergentist models. In so doing, I will assert that Schelling’s Spinoza-inspired

approach to nature-as-ground both fails actually to explain the genesis of subjectivity as well as

amounts to an implausible and not-at-all-materialist anthropomorphic panpsychism.

Correspondingly, I will indicate that Žižek would do better to stick to his habitual Hegelian guns

in philosophically appropriating natural scientific content. Doing so would enable him to

articulate a dialectical Naturphilosophie consistent with his core materialist commitments.

10(F.W.J. Schelling, Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom [trans. Jeff Love and

Johannes Schmidt], Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006, pg. 21-22, 29-33)

Žižek’s long-standing choice of the “quantum physics with Schelling” combination is, I will

contend, inconsistent with the dialectical materialism Žižek continues valiantly to advocate.

Despite appearances to the contrary, Schelling is a faux ami of both materialism and naturalism.

As I will show, when he speaks of “matter” (Materie) and “nature” (Natur), he actually is

invoking God and Spirit, the intangible mind of a divine creator.

§2 Giving Layers Their Just Deserts: Schellingian and Hegelian Freiheitskämpfe

My first task here, proving that Schelling and Hegel are emergentists avant la lettre, is

not too difficult. Nonetheless, the accomplishment of this task is called for up front due to the

likelihood of facing two types of resistance to aligning Schelling and/or Hegel with some sort of

emergentism. The first type is a general history-of-ideas worry about anachronism, since the

explicit forwarding of the notion of emergence as per emergentism(s) postdates the era of

German idealism. I believe that the textual evidence I soon will put forward more than

adequately allays any concerns to the effect that attributing emergentist sensibilities to Schelling

and Hegel is at all anachronistic. In fact, this evidence makes a compelling case for identifying

Schelling and Hegel as two key forefathers of emergentist thinking.

The second type of resistance to interpreting Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophies as

involving emergentism(s) is tied to construals of them as metaphysicians of a static, eternal

Absolute. If the ontological foundations of their systems is indeed some kind of timeless,

unchanging One-All, then any and all emergences could feature in their systems only as

epiphenomena qua mere misleading appearances. Although such commonplace impressions of

Schellingian and/or Hegelian metaphysics cannot be thoroughly scrutinized here—doing so

would derail my focus on the Schelling-Hegel divergence apropos emergentism as it relates to

the Žižek of interest to me in this context—suffice it for now to say that I am convinced these

impressions amount to thoroughly inaccurate misimpressions. Both Schelling and Hegel labor

mightily to integrate temporal, genetic, and historical dimensions, ones in which emergences can

and do feature, into the very foundations of their metaphysical edifices (although I believe that

Schelling ultimately fails to achieve such integrations and, along with them, a true emergentism).

Žižek, particularly when reflecting upon quantum physics, heavily favors the middle-

period Schelling of 1809 to 1815. He especially prefers the Freiheitschrift (1809) and the drafts

of the unfinished Weltalter project (1811-1815). This is slightly strange, given that Schelling’s

Naturphilosophie, the component of his corpus evidently most relevant to a philosophical

dialogue with the natural sciences, is developed with the greatest explicitness and detail in his

earlier period. In fact, it is during a stretch from roughly 1797 through 1808 that Schelling

recurrently devotes intense efforts to elaborating a Philosophy of Nature. I will deal with the

emergentism of the middle-period Schelling when I eventually address Žižek’s Schellingian

rendition of recent physics. And, as my illumination of the nature-philosophical emergentism of

the young Schelling immediately to follow will substantiate, the modeling of emergence in such

later texts as the Freiheitschrift and Weltalter drafts is based on Schelling’s pre-1809 work (and

this contrary to the tendency to see Schelling as a thoroughly protean thinker continually

abandoning his prior positions).

The origins of Schelling’s emergentism are to be found in his earliest texts of the

mid-1790s, even before the beginnings of his Naturphilosophie with the 1797 first edition of his

Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature. These initial glimmerings of emergentist sensibilities in the

young Schelling’s pre-1797 writings surface in connection with Spinozism. Of course, Spinoza

arguably is the figure who soon becomes the avowed pivotal forerunner of the Schellingian

philosophies of Nature and Identity—with the entwined elaborations of these philosophies

occupying Schelling throughout the late-1790s and early-1800s.

Schelling, in the sixth of his 1795 Philosophical Letters on Dogmatism and Criticism,

describes Spinoza as being “troubled by… the riddle of the world, the question of how the

absolute could come out of itself and oppose to itself a world?”11 A footnote to this remark

asserts that this riddle remained “unintelligible” to and unanswerable by Spinoza himself.12

Schelling’s concerns here dovetail with his close friend Friedrich Hölderlin’s contemporaneous

musings as expressed in the latter’s 1795 fragment “Über Urtheil und Seyn”13 (with this

fragment, in its playing off of Spinozistic sympathies against the subjectivist transcendental

idealism of J.G. Fichte, foreshadowing Schelling’s eventual rupture with Fichte in 1801).

One fairly could interpret the entirety of Schelling’s oeuvre, the full sweep of his

meandering output up until his death in 1854, as gravitating around this fundamental

philosophical problem Schelling inherits from Spinoza in particular: how and why the

singularity of the Absolute (whether as God, Nature, Infinity, Identity, Indifference, or whatever

other names one gives it) gives rise out of itself to the plurality of non-Absolute entities and

11 (F.W.J. Schelling, “Philosophical Letters on Dogmatism and Criticism,” The Unconditional in Human Knowledge,

pg. 173-175)

12 (Schelling, “Philosophical Letters on Dogmatism and Criticism,” pg. 174)

13 (Friedrich Hölderlin, “Über Urtheil und Seyn” [trans. H.S. Harris], in H.S. Harris, Hegel’s Development I:

Toward the Sunlight, 1770-1801, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972, pg. 515-516)

(F.W.J. Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism [trans. Peter Heath], Charlottesville: University Press of

Virginia, 1978, pg. 135-136)

10

events.14 Or, one could ask, what account is there of the emergence of the Many out of the One?

Posing Schelling’s line of interrogation of Spinozism in Spinoza’s own terms, how and why does

the unity of substance refract itself into the plurality of attributes and modes? Schelling’s

extensive philosophical body of work, including and especially its anticipations of emergentism,

ought to be understood as motivated by this red thread of metaphysical inquiry. As Schelling

puts it in a polemic against Fichte in 1806, this Spinoza-bequeathed problematic is “the great

question” (die große Frage).15 In another polemic from 1811, one directed against F.H. Jacobi,

Schelling calls this same problematic “the cross of philosophy” (das Kreuz der Philosophie).16

What is more, 1797’s Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, the first elaboration of Schellingian

Naturphilosophie, already pointedly raises this Spinozistic “great question.”17

Informed by Schelling’s immersion in study of the natural sciences circa 1796, Ideas for

a Philosophy of Nature reflects an appreciation by Schelling of eighteenth-century

historicizations of nature. Well before Charles Darwin’s 1859 On the Origin of Species,

14 (Schelling, The Philosophy of Art, pg. 36)

(Schelling, “On Construction in Philosophy,” pg. 285)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Propädeutik der Philosophie, Ausgewählte Schriften: Band 3, 1804-1806, pg. 105-106)

(Schelling, The Ages of the World, Book One: The Past (Original Version, 1811), pg. 74)

(Schelling, “Notes and Fragments to the First Book of The Ages of the World: The Past,” pg. 211, 228)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Der Monotheismus, Sämmtliche Werke [ed. K.F.A. Schelling], zweiter Band, Stuttgart and

Augsburg: Cotta, 1857, pg. 39)

(F.W.J. Schelling, On the History of Modern Philosophy [trans. Andrew Bowie], Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1994, pg. 71-72)

(Xavier Tilliette, Schelling, une philosophie en devenir, 1: Le système vivant, Paris: Vrin, 1992 [second edition], pg.

136, 458)

(Bernd-Olaf Küppers, Natur als Organismus: Schellings frühe Naturphilosophie und ihre Bedeutung für die

moderne Biologie, Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann, 1992, pg. 52)

(Jean-Marie Vaysse, Totalité et subjectivité: Spinoza dans l’idéalisme allemand, Paris: Vrin, 1994, pg. 152)

(S.J. McGrath, The Dark Ground of Spirit: Schelling and the Unconscious, New York: Routledge, 2012, pg. 86)

15 (F.W.J. Schelling, Darlegung Des Wahren Verhältnisses Der Naturphilosophie Zu Der Verbesserten Fichte'schen

Lehre: Eine Erläuterungschrift der ersten, Tübingen: Cotta, 1806, pg. 87)

(Schelling, Statement on the True Relationship of the Philosophy of Nature to the Revised Fichtean Doctrine, pg. 68)

16 (F.W.J. Schelling, Denkmal der Schrift von den göttlichen Dingen ec. des Herrn Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi und

der ihm in derselben gemachten Beschuldigung eines absichtlich tauschenden, Lüge redenden Atheismus, Friedrich

Wilhelm Joseph von Schellings sämmtliche Werke, Band 8 [ed. K.F.A. Schelling], Stuttgart-Augsburg: Cotta, 1861,

pg. 77)

17 (Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, pg. 27-28, 46-47)

11

geological and biological natural histories known to Schelling and his contemporaries (including

Hegel) already eroded long-established traditional pictures of nature as an ahistorical realm of

eternally recurring cycles. Indeed, in 1802’s On University Studies, Schelling associates geology

with “the history of nature” (Historie der Natur selbst),18 an association resurfacing in his later

work too.19 This same 1802 Schelling also declares more sweepingly that, “A truly historical

construction of organic nature would give us the real, objective aspect of the universal science of

nature” (Die historische Konstruktion der organischen Natur würde, in sich vollendet, die reale

und objektive Seite der allgemeinen Wissenschaft derselben).20 The 1811 first draft of the

Weltalter project also emphasizes the significance and profundity of recognizing the depths of

nature’s history21 (with geology’s “ages of the world” inspiring the Weltalter endeavor22).

Relatedly, the notes and fragments for this 1811 first draft go so far as to identify history as the

“highest science”23 (an identification repeated in the 1813 second draft of the Weltalter

project24). Even later, in 1830’s Einleitung in die Philosophie, the history of nature is identified

as also being the history of humanity, with the latter as an outgrowth of the former.25 And, the

registration of the becoming-historical of nature itself already shows up in multiple ways within

the pages of Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature.

18 (F.W.J. Schelling, Vorlesungen über die Methode (Lehrart) des academischen Studiums, Hamburg: Felix Meiner,

1990, pg. 123)

(F.W.J. Schelling, On University Studies [trans. E.S. Morgan], Athens: Ohio University Press, 1966, pg. 128)

19 (F.W.J. Schelling, “Inaugural Lecture (Munich, 26 November 1827),” Philosophy of Revelation (1841-42) and

Related Texts, pg. 24-25)

20 (Schelling, Vorlesungen über die Methode (Lehrart) des academischen Studiums, pg. 137)

(Schelling, On University Studies, pg. 142)

21 (Schelling, The Ages of the World, Book One: The Past (Original Version, 1811), pg. 60, 63, 67)

22 (Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 132-133)

(Hans Jörg Sandkühler, “Natur und geschichtlicher Prozeß: Von Schellings Philosophie der Natur und der Zweiten

Natur zur Wissenschaft der Geschichte,” Natur und geschichtlicher Prozeß: Studien zur Naturphilosophie F.W.J.

Schellings [ed. Hans Jörg Sandkühler], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1984, pg. 21)

23 (Schelling, “Notes and Fragments to the First Book of The Ages of the World: The Past,” pg. 186)

24 (F.W.J. Schelling, Ages of the World (second draft, 1813) [trans. Judith Norman], in Slavoj Žižek and F.W.J.

Schelling, The Abyss of Freedom/Ages of the World, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997, pg. 113-114)

25 (Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 132)

12

The Schelling of this 1797 text speaks both of “a natural history of our mind” (eine

Naturlehre unseres Geistes)26 (suggesting that the transcendental subject itself is a product of

historical nature) as well as of “a hierarchy of life in Nature” (eine Stufenfolge des Lebens in der

Natur)27 (with the mind produced by natural history at the pinnacle of this hylozoistic order). In

this same work, he likewise talks about the immanent genesis of individuated minded

subjectivity out of anonymous worldly objectivity.28 Furthermore, Schelling posits a material

basis as the original foundation of all these generative processes—“Matter is the general seed-

corn of the universe, in which is hidden everything that unfolds in the later developments” (Die

Materie ist das allgemeine Samenkorn des Universums, worin alles verhüllt ist, was in den

spätern Entwicklungen sich entfaltet).29 As will be seen later, recourse to Spinoza’s natura

naturans lurks behind the word “matter” (die Materie) here. This word thereby is somewhat

misleading—and this due to the fact that “matter” just as easily, and more often, connotes the

opposite, namely, Spinoza’s natura naturata.

Despite whatever twists, turns, and discrepancies in Schelling’s claims after 1797, these

just-cited assertions from Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, itself inaugurating Schellingian

Naturphilosophie proper, are echoed repeatedly in subsequent texts. To begin with, the emphasis

26 (F.W.J. Schelling, Einleiting zu: Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur als Einleitung in das Studium dieser

Wissenschaft, Ausgewählte Schriften: Band 1, 1794-1800 [ed. Manfred Frank], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp,

1985, pg. 277)

(Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, pg. 30)

27 (Schelling, Einleiting zu: Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur als Einleitung in das Studium dieser Wissenschaft,

pg. 284)

(Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, pg. 35)

28 (Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, pg. 46-47, 133-134)

29 (F.W.J. Schelling, Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur als Einleitung in das Studium dieser Wissenschaft, Berlin:

Holzinger, 2016, pg. 319)

(Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, pg. 179)

13

on the genetic, on movements of (self-)stratifying becoming, remains constant.30 These geneses

give rise to what arguably are emergent properties and phenomena,31 with Schelling referring to

such unfurling levels and layers as “stages” (Stufen) and/or “potencies” (Potenzen).32 In this

vein, 1799’s First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature identifies as “the fundamental

task of all nature philosophy: TO DERIVE THE DYNAMIC GRADUATED SEQUENCE OF

STAGES IN NATURE” (die Grundausgabe der ganzen Naturphilosophie: die dynamische

Stufenfolge in der Natur abzuleiten).33 This same Schelling refers to “a dynamically graduated

scale in Nature” (eine dynamische Stufenfolge in der Natur)34 and announces that one of the

primary tasks of Naturphilosophie is to illuminate “the intermediate links in the chain of Nature”

30 (F.W.J. Schelling, Allgemeine Deduction des dynamischen Processes oder der Categorieen der Physik, Zeitschrift

für spekulative Physik: Ersten Bandes, erstes Heft, Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik, pg. 103-104)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Allgemeine Deduction des dynamischen Processes (Beschluss der im ersten Heft abgebrochenen

Abhandlung), Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik: Ersten Bandes, zweites Heft, Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik, pg.

83-84)

(Schelling, The Ages of the World, Book One: The Past (Original Version, 1811), pg. 60, 67-68)

(Schelling, “Notes and Fragments to the First Book of The Ages of the World: The Past,” pg. 218)

(Steffen Dietzsch, “Geschichtsphilosophische Dimensionen der Naturphilosophie Schellings,” Natur und

geschichtlicher Prozeß, pg. 246)

(Patrick Cerutti, La philosophie de Schelling: Repères, Paris: Vrin, 2019, pg. 111)

31 (Schelling, Anhang zu dem Aufsatz des Herrn Eschenmayer betreffend den wahren Begriff der Naturphilosophie,

und die richtige Art ihre Probleme aufzulösen, pg. 120)

(Manfred Buhr, “Geschichtliche Vernunft und Naturgeschichte: »Neue« Anmerkungen zur Differenz des

Fichteschen und Schellingschen Systems der Philosophie,” Natur und geschichtlicher Prozeß, pg. 227)

(John H. Zammito, The Gestation of German Biology: Philosophy and Physiology from Stahl to Schelling, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2018, pg. 326)

32 (Schelling, Presentation of My System of Philosophy, pg. 194)

(Schelling, The Ages of the World, Book One: The Past (Original Version, 1811), pg. 84)

(Schelling, “Notes and Fragments to the First Book of The Ages of the World: The Past,” pg. 206, 217, 232-233,

235)

(Schelling, Ages of the World (second draft, 1813), pg. 156-157, 177-178)

(Schelling, Philosophy of Revelation, pg. 51)

33 (F.W.J. Schelling, Erster Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie, Ausgewählte Schriften: Band 1,

1794-1800, pg. 322)

(F.W.J. Schelling, First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature [trans. Keith R. Peterson], Albany: State

University of New York Press, 2004, pg. 6)

34 (F.W.J. Schelling, Einleitung zu dem Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie, oder, über den Begriff der

speculativen Physik und die innere Organisation eines Systems dieser Wissenschaft, Ausgewählte Schriften: Band 1,

1794-1800, pg. 370)

(F.W.J. Schelling, “Introduction to the Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, or, On the Concept of

Speculative Physics and the Internal Organization of a System of This Science,” First Outline of a System of the

Philosophy of Nature, pg. 215)

14

(aller Zwischenglieder im Zusammenhang der Natur)35 conjoining the Alpha and Omega of

nature’s dynamical “Stufenfolge.” Similarly, in a 1801 Jena lecture, Schelling portrays nature as

evolutionary—“everything is just evolution in living nature!” (in der lebenden Natur ist alles nur

Evolution!).36 He continues to think of nature as evolutionary throughout his career.37

Furthermore, Schelling, throughout the late 1790s and early 1800s, remains adamant that

real material nature is the ontological ground-zero for genetic processes or emergences.38 As he

puts it in his 1801 Presentation of My System of Philosophy, “Matter is the prime existent” (Die

Materie ist das primum Existens).39 Likewise, in Schelling’s 1804 Würzburg lectures on the

Philosophy of Nature, he stresses the metaphysical primacy of “the Earth principle” (das

Erdprincip).40 Already in 1799, Schelling vehemently insists that, “the ideal must arise out of

the real and admit of explanation from it” (das Ideelle… aus dem Reellen entspringen und aus

ihm erklärt werden muß).41 The real in question here is initially material nature and the ideal is

35 (Schelling, Einleitung zu dem Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie, oder, über den Begriff der

speculativen Physik und die innere Organisation eines Systems dieser Wissenschaft, pg. 347)

(Schelling, “Introduction to the Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, or, On the Concept of Speculative

Physics and the Internal Organization of a System of This Science,” pg. 199)

36 (F.W.J. Schelling, Hauptmomente aus Schellings Vortrage nach der Stunde aufgezeichnet [ed. Ignaz Paul Vital

Troxler], in F.W.J. Schelling and G.W.F. Hegel, Schellings und Hegels erste absolute Metaphysik (1801-1802) [ed.

Klaus Düsing], Köln: Jürgen Dinter, 1988, pg. 33-34)

(Marie-Luise Heuser-Keßler, Die Produktivität der Natur: Schellings Naturphilosophie und das neue Paradigma

der Selbstorganisation in den Naturwissenschaften, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1986, pg. 103)

37 (Schelling, Philosophy of Revelation, pg. 211)

(Robert J. Richards, The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2002, pg. 11, 211, 225, 298-299, 306)

38 (Schelling, Presentation of My System of Philosophy, pg. 167, 169)

(Schelling, Allgemeine Deduction des dynamischen Processes oder der Categorieen der Physik, pg. 109)

(Schelling, On the History of Modern Philosophy, pg. 118)

(Judith E. Schlanger, Schelling et la réalité finie: Essai sur la philosophie de la Nature et de l’Identité, Paris:

Presses Universitaires de France, 1966, pg. 63)

39 (F.W.J. Schelling, Darstellung meines Systems der Philosophie, Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik: Zweyten

Bandes, zweytes Heft, Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik, pg. 37)

(Schelling, Presentation of My System of Philosophy, pg. 163)

40 (Schelling, System der gesammten Philosophie und der Naturphilosophie insbesondere, pg. 379)

41 (Schelling, Einleitung zu dem Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie, oder, über den Begriff der

speculativen Physik und die innere Organisation eines Systems dieser Wissenschaft, pg. 340)

(Schelling, “Introduction to the Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, or, On the Concept of Speculative

Physics and the Internal Organization of a System of This Science,” pg. 194)

15

ultimately transcendental subjectivity.42 The Philosophy of Nature is charged with furnishing the

clarification (die Erklärung) of this rise of ideality out of reality, the springing (entspringen) of

the former out of the latter.43

Schelling views nature’s sequence of stages (Stufenfolge) as exhibiting a clear

hierarchical order. As just observed, pre/non-human materiality or earthiness is at the bottom of

this hierarchy as the initial moment, form, or incarnation of nature. At the other extreme, the

uppermost strata in the succession of natural levels and layers are those of life, sentience, and, at

the very topmost tier, sapience.

In an ordering later also reflected in Hegel’s Naturphilosophie (as per the second volume

of his three-volume Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences), Schelling sketches a

hierarchical Stufenfolge running from lowest to highest as follows: the physical, the chemical,

the organic, the sentient, and, finally, the sapient.44 In the next section of this intervention, I will

scrutinize the first moment of this series, the physical as Schelling understands it, in a critical

manner. For now, I will highlight two phase transitions, so to speak, in the Schellingian natural

hierarchy: first, the move from the inorganic (encompassing both physics and inorganic

chemistry) to the organic; and, second, the move from animal sentience to human sapience.

Schelling repeatedly identifies the organic as a “higher potency” (höhern Potenz) in

relation to the inorganic.45 However, he carefully stipulates, as he puts it in the First Outline of a

System of the Philosophy of Nature, that, “life is a product of a potency higher than the merely

42 (Schelling, Allgemeine Deduction des dynamischen Processes (Beschluss der im ersten Heft abgebrochenen

Abhandlung), pg. 84)

43 (Schelling, Ages of the World (second draft, 1813), pg. 180)

44 (Schelling, Hauptmomente aus Schellings Vortrage nach der Stunde aufgezeichnet, pg. 57)

(Schelling, “Notes and Fragments to the First Book of The Ages of the World: The Past,” pg. 249-250)

45 (Schelling, Allgemeine Deduction des dynamischen Processes oder der Categorieen der Physik, pg. 102)

16

chemical, but without being supernatural.”46 This 1799 stipulation signals that Schelling not

only is an emergentist avant la lettre—the very notion of “potencies” or “powers” already signals

this—but aspires to be a strong-qua-anti-reductive (rather than weak-qua-reductive) emergentist.

Indeed, Schelling proposes that each and every emergent proper power/potency of nature enjoys

a degree of relative absoluteness in the sense of self-sufficiency as both ontological and

epistemological irreducibility to any other power/potency.47

For Schelling, the organic risks appearing “supernatural” in relation to the natural if and

when the latter is taken in the sense of the inorganic, of the lower levels of physics and

chemistry. This appearance is due to life coming to exhibit structures and dynamics (such as its

own mereological [self-]organizations and teleological final causalities) not exhibited by merely

physical or chemical entities and events. Also in First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of

Nature, Schelling indeed maintains that sentient organisms in particular (i.e., non-human

animals) achieve a degree of autonomy, of self-determination, over-and-above their physical and

chemical determinants (with these determinants serving as underlying natural conditions for

organisms coming into being).48 In 1800’s System of Transcendental Idealism, Schelling even

goes so far as to portray “organic nature” as “at war against an inorganic nature” (im Kampf

gegen eine anorganische Natur).49 Yet, despite sentient organisms’ relative (but not absolute)

freedom from the immediate efficient-causal influences of physical and chemical nature, the

organic both arises out of the inorganic and continues to be affected by the latter. The war of

46 (Schelling, First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, pg. 68)

47 (Schelling, The Philosophy of Art, pg. 14-15)

48 (Schelling, First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, pg. 147)

49 (F.W.J. Schelling, System des transzendentalen Idealismus, Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 2000, pg. 163)

(Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism, pg. 125)

17

organic against inorganic nature is a matter of nature being at war with itself,50 with the First

Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature and its separate introductory presentation

characterizing life as a matter of nature contra nature.51 Emergentism, not matter how strong, is

still not dualism.

Furthermore, Schelling proceeds to identify the species homo sapiens as marking another

major emergent rupture, involving spirit’s “struggle for freedom” (Befreiungskampf) from

nature,52 within nature’s “sequence of stages”—with the genetic jump from the inorganic to the

organic being a preceding major emergent rupture (although, as I soon will demonstrate, the leap

from the inorganic to the organic is not the first Schellingian leap, despite appearing to be so).

Schelling identifies humanity as demarcating the end of animality and the beginning of a natural

stage (Stufe) moving beyond nature’s organic strata—“the human structure (der menschlichen

Bildung)… because it marks the terminal point (die vollendetste) in the series, stands at the limit

of the organic world (der Grenze der Organisation).”53

Likewise, Schelling holds up the human central nervous system as the most glorious

product of organic nature’s productivity. In 1801’s Presentation of My System of Philosophy, he

asserts that, “the brain (das Gehirn)… is the highest product (das höchste Product),”54 promptly

adding poetically that, “Just as the plant bursts forth in the bloom, so the entire earth blossoms in

50 (Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 140)

51 (Schelling, First Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, pg. 160)

(Schelling, “Introduction to the Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, or, On the Concept of Speculative

Physics and the Internal Organization of a System of This Science,” pg. 230)

52 (F.W.J. Schelling, “Treatise Explicatory of the Idealism in the Science of Knowledge,” Idealism and the Endgame

of Theory, pg. 93-94)

(Schelling, Philosophy of Revelation, pg. 256)

(Schelling, On the History of Modern Philosophy, pg. 120)

(Richards, The Romantic Conception of Life, pg. 136)

53 (Schelling, Vorlesungen über die Methode (Lehrart) des academischen Studiums, pg. 136)

(Schelling, On University Studies, pg. 141)

54 (Schelling, Darstellung meines Systems der Philosophie, pg. 123)

(Schelling, Presentation of My System of Philosophy, pg. 203)

18

the human brain, which is the most sublime flower of the entire process of organic

metamorphosis” (Wie die Pflanze in der Blüthe sich schließt, so die ganze Erde im Gehirn des

Menschen, welches die höchste Blüthe der ganzen organischen Metamorphose ist).55 In tandem

with this, Schelling, in 1807’s Über das Verhältnis der bildenden Künste zu der Natur, depicts

human consciousness as a sort of phase transition through which animal sentience reaches its

fullest flowering and, in so doing, tips over into more-than-animal sapience.56 In 1830, Schelling

depicts the fullest-fledged subjectivity of homo sapiens as nature achieving its own liberation

and self-spiritualization.57

In Schelling’s account, human beings represent the moment of the ideal bursting forth out

of the real.58 By his reckoning, humans are the highest ideal potency at the very apex of the

natural Stufenfolge.59 Especially during the period from 1797 to 1801 when Schelling is

struggling to renegotiate his relationship with Fichte-the-transcendental-idealist in light of

Schelling’s invention of Naturphilosophie—Fichte’s refusal to admit the validity of the

Philosophy of Nature eventually prompts Schelling to break with his former mentor—this

transition from real to ideal is meant to be reflected in the division of philosophy into

Naturphilosophie (foregrounding the real) and transcendental idealism (foregrounding the

ideal).60 Several times, Schelling emphasizes that minded and like-minded conscious and self-

55 (Schelling, Darstellung meines Systems der Philosophie, pg. 124)

(Schelling, Presentation of My System of Philosophy, pg. 204)

56 (F.W.J. Schelling, Über das Verhältnis der bildenden Künste zu der Natur, Ausgewählte Schriften: Band 2,

1801-1803 [ed. Manfred Frank], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1985, pg. 589-590)

57 (Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 140)

58 (Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 50)

59 (Schelling, System der gesammten Philosophie und der Naturphilosophie insbesondere, pg. 451-453, 500-501)

(Schelling, Ages of the World (second draft, 1813), pg. 144)

(Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 50)

(Schelling, Philosophy of Revelation, pg. 51-52, 77-78, 174-175)

(Schlanger, Schelling et la réalité finie, pg. 66-67)

60 (Schelling, Allgemeine Deduction des dynamischen Processes (Beschluss der im ersten Heft abgebrochenen

Abhandlung), pg. 84)

19

conscious sapient subjectivity, as per Kantian and Fichtean transcendental idealism, is the highest

emergent power/potency arising out of a dynamic, historicized nature, as per his Philosophy of

Nature.61 As Dieter Sturma suggests, Schelling’s Naturphilosophie is fundamentally motivated

by a desire to account for the transcendental subjectivity of his immediate predecessors.62

Sturma soon goes on to add, “since nature is temporally prior, then subjectivity itself… acquires

the form of an intrinsically altered nature.”63

1800’s System of Transcendental Idealism is a transitional work in which Schelling

attempts to compromise with Fichte so as to smooth over what the latter perceives as a

fundamental, insurmountable incompatibility between transcendental idealism and

Naturphilosophie. Therein, Schelling portrays transcendental and natural philosophies as

equiprimordial, parallel, and supportive of each other.64 In this portrayal, transcendental idealism

61 (Schelling, Anhang zu dem Aufsatz des Herrn Eschenmayer betreffend den wahren Begriff der Naturphilosophie,

und die richtige Art ihre Probleme aufzulösen, pg. 121, 128-129)

(F.W.J. Schelling, Der Ferneren Darstellungen aus dem System der Philosophie, Andrer Theil, Neue Zeitschrift für

speculative Physik: Ersten Bandes, zweites Stück, Neue Zeitschrift für speculative Physik, pg. 51)

(Wolfdietrich Schmied-Kowarzik, “Zur Dialektik des Verhältnisses von Mensch und Natur: Eine

philosophiegeschichtliche Problemskizze zu Kant und Schelling,” Natur und geschichtlicher Prozeß, pg. 162)

(Dietzsch, “Geschichtsphilosophische Dimensionen der Naturphilosophie Schellings,” pg. 241-242)

(Wolfram Hogrebe, Prädikation und Genesis: Metaphysik als Fundamentalheuristik im Ausgang von Schellings

»Die Weltalter«, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1989, pg. 23-24, 118)

(Andrew Bowie, Schelling and Modern European Philosophy: An Introduction, New York: Routledge, 1993, pg.

34)

(Rudolf Brandner, Natur und Subjektivität: Zum Verständnis des Menschseins im Anschluß an Schellings

Grundlegung der Naturphilosophie, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2002, pg. 52)

(Markus Gabriel, Transcendental Ontology: Essays in German Idealism, London: Continuum, 2011, pg. xix-xx, 3,

60)

(Freud Rush, “Schelling’s critique of Hegel,” Interpreting Schelling: Critical Essays [ed. Lara Ostaric], Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2014, pg. 222-223)

(Zammito, The Gestation of German Biology, pg. 319)

62 (Dieter Sturma, “The Nature of Subjectivity: The Critical and Systematic Function of Schelling’s Philosophy of

Nature,” The Reception of Kant’s Critical Philosophy: Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel [ed. Sally Sedgwick],

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pg. 219-220)

63 (Sturma, “The Nature of Subjectivity,” pg. 223)

64 (Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism, pg. 2-3, 7)

(Schelling, “Introduction to the Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, or, On the Concept of Speculative

Physics and the Internal Organization of a System of This Science,” pg. 194)

(Schelling, Anhang zu dem Aufsatz des Herrn Eschenmayer betreffend den wahren Begriff der Naturphilosophie,

und die richtige Art ihre Probleme aufzulösen, pg. 116)

20

prioritizes the subjective ideal as epistemologically generative of the objective real, whereas the

Philosophy of Nature prioritizes the objective real as ontologically generative of the subjective

ideal.65 However, both before and after the System of Transcendental Idealism, Schelling denies

this balanced fifty-fifty weighting of importance between the transcendental and the natural,

clearly emphasizing the ontological and epistemological primacy of Naturphilosophie over

transcendental idealism.66 It should not have come as a shock to him that Fichte was unmoved

by the suspicious olive branch extended in Schelling’s 1800 text.

This noted, a certain continuity between the System of Transcendental Idealism and the

Philosophy of Nature of the late 1790s and early 1800s warrants attention. By 1800, as seen,

Schelling already has situated the subjectivity of transcendental idealism at the highest levels of

nature’s hierarchical succession of stages. In this picture, the transcendental subject is the

ultimate emergent product of a dynamic nature producing a whole series of emergent strata

leading up to the genesis of this subject. Much later, in 1834, Schelling characterizes this as a

matter of grounding “psychology” in ontology.67

The System of Transcendental Idealism then further enriches this picture by introducing a

series of genetic levels and layers within the structure of transcendental subjectivity, namely, by

narrating processes in and through which this subject unfolds itself and achieves self-

65 (Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism, pg. 7, 14)

(Schelling, “Introduction to the Outline of a System of the Philosophy of Nature, or, On the Concept of Speculative

Physics and the Internal Organization of a System of This Science,” pg. 193, 196-197)

66 (Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, pg. 41-42. 53-55)

(Schelling, Anhang zu dem Aufsatz des Herrn Eschenmayer betreffend den wahren Begriff der Naturphilosophie,

und die richtige Art ihre Probleme aufzulösen, pg. 128-129)

(Schelling, Der Ferneren Darstellungen aus dem System der Philosophie, Andrer Theil, pg. 51)

(Schelling, On University Studies, pg. 122-123)

(Schelling, System der gesammten Philosophie und der Naturphilosophie insbesondere, pg. 504)

(Schelling, Philosophy and Religion, pg. 8)

67 (F.W.J. Schelling, Vorrede zu einer philosophischen Schrift des Herrn Victor Cousin, Ausgewählte Schriften:

Band 4, 1807-1834 [ed. Manfred Frank], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1985, pg. 626)

21

consciousness68 (Schelling’s 1800 treatise indeed anticipates certain core aspects of Hegel’s 1807

Phenomenology of Spirit). Ideal subjectivity, as well as the real nature from which it allegedly

emerges, contains emergent dimensions within itself. The System of Transcendental Idealism

appeals to Kant’s own hints about the genetic dimensions of the “I”69 and characterizes

transcendental philosophy properly construed as “a history of self-consciousness, having various

epochs” (eine Geschichte des Selbstbewußtseins, die verschiedene Epochen hat).70 These

“epochs” can be understood as the equivalent within transcendental subjectivity of emergent

powers/potencies within nature.

Despite portraying the ideality of transcendental subjectivity as arising from the reality/

materiality of nature, the anti-reductive aspirations of Schelling’s variety of (proto-)emergentism

is on display in his System of Transcendental Idealism. Therein, he asserts that, “the spirit is

everlastingly an island, never to be reached from matter without a leap” (der Geist eine ewige

Insel ist, zu der man durch noch so viele Umwege von der Materie aus nie ohne Sprung gelangen

kann).71 The notion of “leap” (Sprung) suggests that “spirit” (Geist as ideal subjectivity) marks a

break with material nature produced within and out of nothing other than material nature itself.

Schelling’s naturalist account of anthropogenesis hence seemingly would rely upon a strong

68 (Schelling, “Treatise Explicatory of the Idealism in the Science of Knowledge,” pg. 104)

69 (Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism, pg. 31)

(Immanuel Kant, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View [trans. Victor Lyle Dowdell], Carbondale and

Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1978, pg. 9-10, 85, 176)

(Adrian Johnston, Time Driven: Metapsychology and the Splitting of the Drive, Evanston: Northwestern University

Press, 2005, pg. 79-93)

(Adrian Johnston, “Meta-Transcendentalism and Error-First Ontology: The Cases of Gilbert Simondon and

Catherine Malabou,” New Realism and Contemporary Philosophy [ed. Gregor Kroupa and Jure Simoniti], London:

Bloomsbury, 2020, pg. 145-178)

70 (Schelling, System des transzendentalen Idealismus, pg. 67)

(Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism, pg. 50)

71 (Schelling, System des transzendentalen Idealismus, pg. 98)

(Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism, pg. 74)

22

variant of emergentism (with Hegel’s emergentism also definitely being an extremely anti-

reductive sort).

In terms of significant overlaps between Schelling’s and Hegel’s narratives apropos

relations between Natur und Geist, Schelling repeatedly describes a grand-scale arc in which the

entirety of nature eventually generates out of itself sentient animals and sapient humans through

which it comes to experience and even know itself.72 Nature, via its unfurling emergences,

transition from being in-itself (an sich) to for-itself (für sich) once it produces from within itself

sentience and sapience.73 This Schellingian story anticipates and likely inspires Hegel’s

substance-also-as-subject motif recurring throughout his mature works.74

Having established Schelling’s proto-emergentist credentials, I turn now to doing the

same for Hegel. However, my task in Hegel’s case is much easier—and this for several reasons.

To begin with, I already argue in detail for an emergentism-avant-la-lettre in the Hegelian edifice

on prior occasions.75

72 (Schelling, Philosophy of Revelation, pg. 158-160, 162, 222)

73 (Schelling, Allgemeine Deduction des dynamischen Processes (Beschluss der im ersten Heft abgebrochenen

Abhandlung), pg. 86-87)

(Schelling, Hauptmomente aus Schellings Vortrage nach der Stunde aufgezeichnet, pg. 36)

(Schelling, System der gesammten Philosophie und der Naturphilosophie insbesondere, pg. 442, 444, 466-467)

(Schelling, Einleitung in die Philosophie, pg. 42-43)

74 (Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, pg. 9-10)

(G.W.F. Hegel, Philosophy of Mind: Part Three of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences [trans. A.V.

Miller], Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, §573 [pg. 309-310])

(G.W.F. Hegel, Lectures on Logic: Berlin, 1831 [trans. Clark Butler], Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008,

§212-213 [pg. 212], §235 [pg. 227])

(Johnston, Adventures in Transcendental Materialism, pg. 23-49)

(Johnston, A New German Idealism, pg. 11-37)

(Adrian Johnston, Prolegomena to Any Future Materialism, Volume Two: A Weak Nature Alone, Evanston:

Northwestern University Press, 2019, pg. 15-69)

(Adrian Johnston, “The Difference Between Fichte’s and Hegel’s Systems of Philosophy: A Response to Robert

Pippin,” Pli: The Warwick Journal of Philosophy, special issue: “Hegel and the Sciences: Philosophy of Nature in

the Twenty-First Century” [ed. Filip Niklas], no. 31, 2019, pg. 1-68)

75 (Johnston, Adventures in Transcendental Materialism, pg. 23-49)

(Johnston, Prolegomena to Any Future Materialism, Volume Two, pg. 15-69)

(Johnston, “The Difference Between Fichte’s and Hegel’s Systems of Philosophy,” pg. 1-68)

23

Furthermore, as I have hinted intermittently throughout the preceding, I see Hegel as

embracing and carrying forward multiple features of the early Schelling’s Naturphilosophie in

particular (and this despite him also being quite critical of it76). These features include: the

sequencing of the dynamic stages of nature (physical, chemical, organic, sentient, and sapient)77;

treating transcendental subjectivity itself as a product of pre/non-subjective being, with

transcendental idealism in need of an underlying nature-philosophical ontology; and,

comprehending the subject as substance sensing and grasping itself. That is to say, Hegel shares

with Schelling—he continues to do so even after these former friends and allies become

estranged from each other following the publication of the Phenomenology of Spirit—

commitment to a proto-emergentism as central to a partly naturalistic ontology beyond Kantian

and Fichtean transcendental idealisms (with their anti-naturalisms). As for the nonetheless

significant differences between Schelling and Hegel, I will address those later in connection with

my considerations apropos Žižek.

My account of Hegelian emergentism, in a context in which Schellingian emergentism

also is under examination, will focus on the second volume of Hegel’s Encyclopedia, namely, the

Philosophy of Nature. However, the earlier Science of Logic already contains an important

remark relevant to my concerns here. Near the end of “The Doctrine of Being,” during the

discussion of the dialectics of quality, quantity, and measure, Hegel turns his attention to the old

76 (G.W.F. Hegel, Philosophy of Nature: Part Two of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences [trans. A.V.

Miller], Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970, pg. 1, §246 [pg. 10], §359 [pg. 385-388])

(G.W.F. Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy: Volume Three [trans. E.S. Haldane and Frances H. Simson],

New York: Humanities Press, 1955, pg. 529, 541-545)

77 (G.W.F. Hegel, The Jena System, 1804-5: Logic and Metaphysics [ed. John W. Burbidge and George di

Giovanni], Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986, pg. 185)

24

bit of supposed wisdom according to which “nature does not make leaps” (natura non facit

saltum).

Hegel proceeds to observe that, “Every birth and death (Alle Geburt und Tod), far from

being a progressive gradualness (eine fortgesetzte Allmählichkeit), is an interruption (ein

Abbrechen) of it and is the leap (der Sprung) from a quantitative into a qualitative alteration.”78

He continues:

It is said, natura non facit saltum; and ordinary thinking when it has to grasp a

coming-to-be or a ceasing-to-be (ein Entstehen oder Vergehen), fancies that it has

done so by representing it as a gradual emergence or disappearance (ein allmähliches

Hervorgehen oder Verschwinden). But… the alterations of being in general are not

only the transition of one magnitude into another, but a transition from quality into

quantity and vice versa, a becoming-other which is an interruption of gradualness

(ein Abbrechen des Allmählichen) and the production of something qualitatively

different from the reality which preceded it.79

Hegel immediately goes on to mention the familiar example of H2O as qualitatively solid, liquid,

or gas at different points along the quantitative temperature scale.80 But, whether the example

be, on the one hand, ice changing to water changing to steam or, on the other hand, birth

following gestation or death following illness, Hegel’s point is the same: Natural processes

indeed are punctuated and marked (or “interrupted” as “ein Abbrechen des Allmählichen”) by

abrupt “leaps” (Sprünge), namely, what nowadays would be called “tipping points” or “phase

transitions.” Later in the Science of Logic, in “The Doctrine of the Concept,” Hegel also refers to

natural “stages” (Stufen) accumulating through emergences.81 Of course, apart from purely

78 (G.W.F. Hegel, Wissenschaft der Logik I, Werke 5, Werke in zwanzig Bänden [ed. Eva Moldenhauer and Karl

Markus Michel], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1969, pg. 440)

(G.W.F. Hegel, Science of Logic [trans. A.V. Miller], London: George Allen & Unwin, 1969, pg. 369-370)

79 (Hegel, Wissenschaft der Logik I, pg. 440)

(Hegel, Science of Logic, pg. 370)

80 (Hegel, Science of Logic, pg. 370)

81 (G.W.F. Hegel, Wissenschaft der Logik II, Werke 6, Werke in zwanzig Bänden [ed. Eva Moldenhauer and Karl

Markus Michel], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1969, pg. 257)

(Hegel, Science of Logic, pg. 586)

25

natural examples, the Russian Marxist tradition, in terms of a historical materialist construal of

socio-political history, subsequently hails Hegel’s dialectics of quality and quantity as “the

algebra of revolution.” Furthermore, these same Hegelian comments on “natura non facit

saltum” subsequently reappear in Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature.82

So then, what about Hegel’s emergentism as per his Philosophy of Nature? The second

volume of the Encyclopedia contains ample evidence to the effect that the mature Hegel, still like

Schelling despite the Phenomenology-precipitated split between them, subscribes to what

defensibly can be characterized as an emergentist model of a material nature eventually

generating out of itself spiritual subjectivity. In the introduction to the Philosophy of Nature,

Hegel offers a description of Spirit’s Befrieungskampf from Nature in which he references

Schelling’s Naturphilosophie:

A rational consideration of Nature (Die denkende Naturbetrachtung) must

consider how Nature is in its own self this process of becoming Spirit, of

sublating its otherness (die Natur an ihr selbst dieser Prozeß ist, zum Geiste

zu werden, ihr Anderssein aufzuheben)—and how the Idea is present in each

grade or level of Nature itself (jeder Stufe der Natur selbst); estranged from

the Idea, Nature is only the corpse of the Understanding (der Leichnam des

Verstandes). Nature is, however, only implicitly (nur an sich) the Idea, and

Schelling therefore called her a petrified intelligence (versteinerte… Intelligenz),

others even a frozen intelligence; but God does not remain petrified and dead;

the very stones cry out and raise themselves to Spirit (heben sich zum Geiste

auf).83

82(Hegel, Philosophy of Nature, §249 [pg. 22])

83(G.W.F. Hegel, Die Naturphilosophie: Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften II, Werke 9, Werke in

zwanzig Bänden [ed. Eva Moldenhauer and Karl Markus Michel], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1978, §247 [pg.

25])

(Hegel, Philosophy of Nature, §247 [pg. 14-15])

26

The young Schelling’s image of nature as congealed or petrified intelligence84 is not the only

Schellingian note sounded in this passage. Both in this quotation and throughout the second

volume of the Encyclopedia, Hegel echoes a number of features of the early Schelling’s

Naturphilosophie.

First of all, there is the idea of nature as a dynamic “process of becoming” unfolding in a

series of “grades or levels” (Stufen). Indeed, Hegel declares that, “Nature is to be regarded as a

system of stages (ein System von Stufen).”85 And, as I already pointed out, these identified

Stufen and their orderly sequencing are more or less the same between Schelling’s and Hegel’s

Naturphilosophien. It also should be appreciated that Hegel associates each emergent stage as a

sublation (Aufhebung) of its genetic predecessors, with Spirit itself as Nature’s immanent self-

sublation (“Nature is in its own self this process of becoming Spirit, of sublating its otherness,”

“the very stones cry out and raise themselves to Spirit [heben sich zum Geiste auf]”).86

Moreover, Hegel shares with Schelling the claim that conscious and self-conscious

spiritual subjectivity is the very pinnacle of a natural hierarchy of emergent strata, being the

highest product of life, with the realm of the organic as the uppermost general tier of nature.87

However, Hegel stipulates that, “mind has for its presupposition Nature” (Der Geist hat für uns

84 (Schelling, Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature, pg. 181)

(Schelling, System of Transcendental Idealism, pg. 6, 30)

(Schelling, The Ages of the World, Book One: The Past (Original Version, 1811), pg. 63)

(G.W.F. Hegel, The Difference Between Fichte’s and Schelling’s System of Philosophy [trans. H.S. Harris and Walter

Cerf], Albany: State University of New York Press, 1977, pg. 165-167))

85 (Hegel, Die Naturphilosophie, §249 [pg. 31])

(Hegel, Philosophy of Nature, §249 [pg. 20])

86 (G.W.F. Hegel, Philosophy of Mind: Part Three of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences [trans. A.V.

Miller], Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, §381 [pg. 13-14], §388-389 [pg. 29-31])

87 (Hegel, Philosophy of Nature, §248 [pg. 17-18], §251 [pg. 25], §252 [pg. 27])

27

die Natur zu seiner Voraussetzung).88 Beginning with the sentient animal organism and reaching

its fullest realization in and through the sapient human subject, natural substance transitions from

unconscious in-itself-ness to self-aware and self-knowing for-itself-ness.89 Speaking of this

movement through which (natural) substance (i.e., “this totality” as the planetary whole of the

earth) becomes also (spiritual) subject, Hegel states:

This totality (Diese Totalität) is the ground (der Grund) and the universal substance

(die allgemeine Substanz) on which is borne what follows. Everything is this totality

of motion but as brought back under a higher being-within-self (höherem Insichsein)

or, what is the same thing, as realized into a higher being-within-self. This being-

within-self contains this totality, but the latter remains indifferently and separately

in the background as a particular existence (ein besonderes Dasein), as a history

(eine Geschichte), or as the origin (der Ursprung) against which the being-for-self

is turned (gegen den das Fürsichsein gekehrt ist), just so that it can be for itself (für

sich zu sein). It lives therefore in this element but also liberates itself (befreit sich)

therefrom, since only weak traces of this element are present in it. Terrestrial being

(Das Irdische), and still more organic and self-conscious being (das Organische und

sich selbst Bewußte), has escaped from the motion of absolute matter (ist der

Bewegung der absoluten Materie entgangen), but still remains in sympathy with

it and lives on it as in its inner element.90

The “being-within-self” (Insichsein) and “being-for-self” (Fürsichsein) would be sentience and

sapience respectively as both moments of the becoming-subject of “universal substance” (die

allgemeine Substanz). The latter is the “totality” (Totalität) of “the motion of absolute matter”

(der Bewegung der absoluten Materie) serving as the “ground” (der Grund) for experiencing and

(self-)knowing beings.

88 (G.W.F. Hegel, Der Philosophie des Geistes: Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften III, Werke 10,

Werke in zwanzig Bänden [ed. Eva Moldenhauer and Karl Markus Michel], Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1970,

§381 [pg. 17])

(Hegel, Philosophy of Mind, §381 [pg. 8])

89 (G.W.F. Hegel, Jenaer Systementwürfe III: Naturphilosophie und Philosophie des Geistes [ed. Rolf-Peter

Horstmann], Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 1987, pg. 262)

90 (Hegel, Die Naturphilosophie, §270 [pg. 104])

(Hegel, Philosophy of Nature, §270 [pg. 81])

28

Furthermore, there is a cross-resonance between moments in the above quotation from

Hegel’s Naturphilosophie and the earlier-cited Schelling of both the First Outline of a System of

the Philosophy of Nature and System of Transcendental Idealism. Specifically, in these 1799 and

1800 texts, Schelling characterizes life, especially human life, as involving portions of nature

coming to individuate themselves by rebelling against the larger natural whole from which they

emerge. Schellingian life is a matter of nature being at war with itself, immanently generating

discord from within and out of itself.

Likewise, in the just-quoted passage, Hegel portrays being-within-and-for-self (i.e.,

spiritual subjectivity) as reacting back against the larger natural background from which it

originates (“the origin (der Ursprung) against which the being-for-self is turned (gegen den das

Fürsichsein gekehrt ist)”). Through this rebellious turning against its substantial base, the

subject “liberates itself” (befreit sich) from efficient-causal determination by mere physics and

chemistry alone. It thereby “escaped from the motion of absolute matter” (ist der Bewegung der

absoluten Materie entgangen). A short while later in his Philosophy of Nature, Hegel similarly

claims that, “the healthy, and more especially minded, creature withdraws itself from this

universal life and opposes itself to it” (das Gesunde und dann vornehmlich das Geistige entreißt

sich diesem allgemeinen Leben und stellt sich ihm entgegen).91 For Schelling and Hegel alike,

both animal organisms and human subjects come to be and sustain themselves partly through

Freiheitskämpfe in which they violently separate themselves from and strike back against the

natural dimensions from which they originally arise.

91(Hegel, Die Naturphilosophie, §279 [pg. 130])

(Hegel, Philosophy of Nature, §279 [pg. 102])

29

On the basis of the immediately preceding, I will highlight one final point of agreement

between the Schelling and the Hegel under consideration here before proceeding to an

engagement with Žižek. In terms of the rapport between nature (as per Schellingian and

Hegelian Naturphilosophien) and subject (as per Schellingian transcendental idealism and

Hegelian Geistesphilosophie), the subject’s transcendence of nature nonetheless remains

immanent to this same nature. With Hegel, evidence of this insistence is visible in the prior

block quotation from the Philosophy of Nature (“weak traces of this element are present in it,”

“still remains in sympathy with it and lives on it as in its inner element”). What is more, the

Philosophy of Mind, the third and final volume of the Encyclopedia, likewise insists on this

simultaneity of immanence and transcendence in Spirit’s relation with Nature (albeit with an

emphasis here on transcendence)—“Mind, as embodied, is indeed in a definite place and in a

definite time; but for all that it is exalted over them” (Der Geist, als verkörpert, ist zwar an

einem bestimmten Ort und in einer bestimmten Zeit, dennoch aber über Raum und Zeit

erhaben).92

As will become evident in what follows, Hegel comes to worry that Schelling,

particularly in the latter’s more Spinozistic moods, cannot adequately preserve the transcendent

side of the simultaneously nature-immanent and nature-transcendent subject. Indeed, Hegel’s

critique of Spinozism, including Schelling’s Spinozism—I have detailed this critique at length

elsewhere93—dovetails with how Hegel’s version of strong emergentism differs from the

emergentism of Schelling. This difference between Hegelian and Schellingian emergentisms

92 (Hegel, Der Philosophie des Geistes, §392 [pg. 54])

(Hegel, Philosophy of Mind, §392 [pg. 38])

93 (Johnston, Adventures in Transcendental Materialism, pg. 13-64)

30

will prove to be central to my assessment of Žižek’s philosophical appropriations of quantum

mechanics. I now turn to this assessment.

§3 The Rabbit and the Hat: Anthropogenesis With and Without Anthropomorphism

For many years now, Žižek has been pursuing a dialectical materialist ontology centrally

including within itself a theory of subjectivity. The subject of this theory originates out of, yet

thereafter becomes irreducible to, pre/non-human nature. The question is not whether Žižek

relies upon some sort of emergentism. Rather, the question is exactly what type of emergentism

he embraces.94 And, given Žižek’s avowed indebtedness to both Schelling and Hegel, revisiting

Žižekian dialectical materialism in light of Schelling’s and Hegel’s (proto-)emergentisms

promises to clarify further Žižek’s core philosophical project.

I will be focusing primarily on Žižek’s 2020 book Sex and the Failed Absolute. I have

chosen this focus for three reasons. First, Sex and the Failed Absolute is Žižek’s most recent

substantial theoretical work. Second, I already have dealt with the bulk of his preceding

philosophical texts in my own prior publications. And, third, Sex and the Failed Absolute

involves Žižek doubling-down specifically on his recourse to quantum physics as integral to his

unique version of dialectical materialism.

Žižek’s initial turn to quantum mechanics occurs in his 1996 book The Indivisible

Remainder, in a chapter entitled “Quantum Physics with Lacan.”95 Perhaps this chapter should

have been entitled “Quantum Physics with Lacan and Schelling,” since the Schellingian

94 (Johnston, Adventures in Transcendental Materialism, pg. 17-18, 125)

(Johnston, A New German Idealism, pg. 141-142, 173-174, 181, 185-186)

95 (Slavoj Žižek, The Indivisible Remainder: An Essay on Schelling and Related Matters, London: Verso, 1996, pg.

189-236)

31

philosophy being explored throughout this 1996 book is as important to its chapter on quantum

matters as is Lacanian psychoanalysis. To be precise, the middle-period Schelling, from 1809’s

Freiheitschrift to 1815’s third and final draft of the unfinished Weltalter project, is Žižek’s

privileged partner (along with Jacques Lacan) in the context of his theoretical borrowings from

quantum physics.

Before carefully considering Žižek’s Schelling-inspired quantum ontology, I need to say a

few things about the Žižek-preferred middle-period Schelling with respect to the early (pre-1809)

Schelling I discussed in some detail above. Many scholars consider the 1809 Freiheitschrift as

marking a break within Schelling’s corpus, a rupture in his intellectual itinerary demarcating a

divide between “early” and “middle” periods. I will not be debating here whether or not a

radical discontinuity occurring in 1809 punctuates the unfolding of Schelling’s thinking. For my

limited present purposes, even if it does so, I would maintain that there nonetheless remain

certain major lines of continuity between the pre-1809 and the 1809-and-after Schelling.

The first of these continuities is Schelling’s commitment to select features of Spinozism

as he construes it. His clarifications and qualifications apropos Spinozism in the Freiheitschrift

testify to how sharply he had been stung by Hegel’s then-fresh 1807 dismissal of the Spinozistic

“night in which all cows are black.”96 Hegel belatedly, in his Berlin Lectures on the History of

Philosophy, registers an appreciation of these clarifications and qualifications insofar as he then

recognizes the Freiheitschrift as “deeply speculative in character.”97

Yet, I would maintain that, whatever caveats Schelling tacks onto his relationship with

Spinoza in 1809, he nevertheless retains certain essential features of Spinozism. More generally,

96 (Schelling, Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom, pg. 12-13, 16-17)

97 (Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy: Volume Three, pg. 514)

32

Schelling’s occasional distance-takings from Spinoza, his scattered criticisms of Spinoza’s

philosophy he voices periodically both before and after 1809, are far outweighed by his frequent