Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Meiksins Wood Citizens To Lords A Social History of Western Political

Meiksins Wood Citizens To Lords A Social History of Western Political

Uploaded by

Roc Solà0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views124 pagesOriginal Title

Meiksins Wood Citizens to Lords a Social History of Western Political

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views124 pagesMeiksins Wood Citizens To Lords A Social History of Western Political

Meiksins Wood Citizens To Lords A Social History of Western Political

Uploaded by

Roc SolàCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 124

CITIZENS

TO LORDS

A Social History of Western Political Thought

From Antiqnity to the Middle Ages

a

ELLEN MEIKSINS WOOD

M

VERSO

tendon « New Yrk

Je

3

Wée

2008

First published by Verso 2008

Copyright © Ellen Meiksins Wood 2008

AML ght reserved

‘The moral nigh of the author has teen asserted

13579108642

Vero

UK. 6 Meand Sucet, Landon WF OFG

USA: 180 Varick Stee, Nevw York, NY 10014-4606

‘wornsersobookscom

Verso isthe imprint of New Left Books

ISEN-3: 978-1-84567-204

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is avilable fom the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data

‘A canal sexo for chin book is available from the Libraty of Congress

“Typeset in Sabor by Hewer Text UK Lad, Edinburgh

Printed in che USA by Maple Vail

In memory of

Neal Wood

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

1 ‘the Social History of Political Theory

2. The Ancient Greek Polis

3. From Polis to Empire

4 The Middle Ages

Conclision

Index

233

27

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

‘As so often before, am particularly grateful 10 George Conmineh

A evread the whole manuscript and made his cnstomarily generous

sna insightful suggestions. My thanks also to Paul Cartledge, Janet

Goleman and Gordon Schochet, who read parts of the manuscript stud

nade uneful vomunents but cannot, of course, he held responsible for

sry failures on my part to take good advice. Perry Anderson kindly

dered to my last-minute request for a quick reading of the whole text

and made some vety helpful suggestions. And special thanks to Ed

Broadbent, who brilliantly played the role of every writer's dream

audience, the intelligent general reader. Lowe a great deal to his keenly

Critical eye, together with his unfailing support and encouragement.

My greatest debt is to Neal Wood. Many years ago, we decided

that one day we would writea social history ot political theory together.

Somchiw we never yor aivund £058. There were always other projects

to embark on and complete. Yet when, after his death, I set out to do

it'on my own, he remained in a sense the co-author. tt was he who

y of Bs ight; it was he

who coined the phrase, the ‘social history of political theory’ and

this project would have been inconceivable without his rich body of

aan hig example of sch

passionate engagement.

cy combined with

THE SOCIAL HISTORY

OF POLITICAL THEORY

‘What is Political Theory?

Feery complex civilization with a state and organized leadership is

bound to generate reflection on the relations between leader and led,

rulers and subjets, command and obedience. Whether it takes the

form of systematic philosophy. poetry, parable or proverb, in oral

traditions or in the written word, we can call it political thought. But

the subject of this book is one very particular mode of political thinking,

that emerged in the very particular historical conditions of ancient

Groece and developed over two millennia in what we nov call Europe

and its colonial ourposts."

For better or worse. the Greeks invented their oven distinctive mode

of political heory, a systematic and analytical interrogation of political

principles, fuli of laboriously constructed definitions auxd adversarial

argumentation, applying critical reason to questioning the very

foundations and legitimacy of traditional moral rules and the principles

‘of political right. While there have been many other ways of thinking

about politics in the Western world, what we think of as the classics

1 Political” though, in an of is forms, assumes the existence of political organ

ization. For the purpess of chis book, shal ell that form of organization the ‘ate’

defining it broadly erengh ra encorspace wide variety of Foers, Frm the pelis al

the ancient bureaucratic kingdom eo the modern nation state ~ alghough throughout

hoods, we chal often have excanion to take note of he differences among various

Pes of state, The state, theny isa “coniplex of institutions by means cf sich the

poner uf die society is organized on a basis superior to kinship an organization of

Power that entails a claim "to parsmountcy in the application of naked force to social

Droblems and consss of “formal, specialized instruments of coercion (Morton ric,

The Evolution of Political Sty. New York: Random House. 1968. pp. 229-30). The

“as embraces les inne intons = howls dans, Knap wows

and performs commen rocal functions that such ineitatons cannot carry ou

2 CITIZENS TO LoRDs

of Western political thought, ancient and modern, belong to the

tradition of political theory established hy the Greeks

‘Other ancient civilizations in many ways more advanced than the

Greeks — in everything from agncultural techniques to commerce,

navigation, and every conceivable craft or high art ~ produced vast

literatures on every human practice, as well as speculations about the

origins of life and the formation of the universe. But, in general, the

political order was not treated as an object of systematic critical

speculation,

‘We can, for example, contrast the ancient Greek mode of political

speculation about principles of political order with the philosophy of

ethical precept, aphorism, advice and example produced by the far

‘more complex and advanced civilization of China, which had its own

tich and varied! tradition of political thought. Confucian philosophy,

for instance, takes the form of aphorisms on appropriate conduct,

proverbial sayings and exemplary anecdotes, conveying its political

Tessons not by means of argumentation but by subule allusions with

complex layers of meaning. Another civilization more advanced than

classical Greece, India, produced a Hindu tradition of political thought

Lacking the hind of analytical and theoretical speu

acterized Indian works of moral philosophy, logic and epistemolozy.

‘expressing its commitment to existing political arrangements in didactic

fou wi

jon that cha

systematic argumentation. We can also contest classical

political philosophy to the earlier Homeric poetry of heroic ideals.

models and examples or even to the political poetry of Solon, on the

eve uf the classical polis.

The tradition of political theory as we know it in the West can be

traced back to ancient Greek philosophers — notably, Protagoras,

Socrates, Plato and Aristotle — and it has produced a series of “canon”

ical’ thinkers whose names have hecome familiar even to those who

hhave never read their work: St Augustine, St Thomas Aquinas,

Machiavelli, Fiobbes, Locke, Kousseau, Hegel, Muli, and so on. the

writings of these thinkers ate exttemely varied, hut they do have certain

things in common. Although they often analyze the state as it is, their

principal enterprise is criticism and prescription. They all have some

conception of what constitutes the right and proper ardering of sociery

and government. What is conceived as ‘right’ is often based on some

conception of justice and the morally good Ife, but st may also deve

from practical reflections about what is required to maintain peace,

security and material well-being,

Some political theorists offer blueprints for an ideally just state.

Others specify reforms of existing government and proposals for

sue SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY 3

sng public policy For all of them, the central questions have to

nt ep ould perm and how, or what form of government is

ge win they generally agree that i is nor enough to ask and answer

ee dons about the fest form of government: we rust ako exiecaly

eet ie grounds on which sich judgments are made. Underlying

cree ations i always some conception of human nature, those

MeGhineoin human beings that must be nurtured or controled in order

seeeilfeve a right and proper social orcler Political theorists have

£° ned their human ideals and asked what kind of social and political

cirernents are required to realize this vision of humanity And when

atest sel as these are ake, others may net be far off why and

sire har conditions ought we to abey those who govern us, and are

swe exer entitled t0 disobey or rebel?

These inay acon obvious questions, but the very idea of asking

them, the ery idea thatthe principles of government or the obligation

toobey authority are proper subjects for systematic rellection and the

Epplicauin of ettieal teason, cannot be taker for granted. Political

theory represents as important a cultural milestone as does systematic

philosophical or scientific reflection on the nature of matter, the earth

find heavenly bodies. If anything, the invention of political cheory i

harder to explain than is the emergence of natucal philosophy and

Th what follows, we shall explore the histovical conditions in which

political theory was invented and how it developed in specific

Historical contexts, always keeping in mind that the classics of

poliical dheory wele wiiten in response t pasticular historical

Circumstances. The periods of greatest cteatvity in politieal theory

have tended to be those historical moments when social and political

confi has erupted in particularly urgent ways, with far-reaching

consequences; but even in calmer times. the questions addressed by

political theorists have presented themselves in historically specific

“This means several thines. Political theorists mav speak to_us

through the centuries. As commentators onthe human condition, they

‘may have something vo say forall times. But they are ike all buat

beings, historical creatures: and we shall have a much richer under-

standing of what they have to say, and even how it might shed light

‘on our own historical moment, when we have some idea of why they

said it to whom they said it with whom they were debating (explicitly

or implicitly), how their immediate world looked to them, and what

hey believed should be changed or preserved. ‘This is nor simply

matter of biographical detail or even historical “background”. To

a CITIZENS TO LORDS

tunderstand what political theorists are saying requires knowing what

‘questions they are trying ta answer, and those questions confront them

‘not simply as philosophical abstractions but as specific problems posed

by specific historical conditions, in the context of specific practical

activities, social relations, pressing issues, grievances and conflicts.

The History of Political Theory

This understanding of political theory as a historical product has not

always prevailed among scholars who write about the history of political

thought; and it probably sill needs to be justified, sot least axainst the

charge that by historicizing the great works of political theory we

ddemean and trivialize them, denying them any meaning and significance

beyond their own historical moutent, Ushall uy w explain and defend

my reasons for proceeding as 1 do, but that reauies, first, a sketch of

how the history of political thought has been studied in the recent past.

In the 19603 asnl 70s, at a tine of sevival for the study of political

theory, academic specialists used to debate endlessly about the nature

and fate of their discipline. But in general political theorists, especially

in American universities, were expected wv embrace he division of

political studies into the ‘empirical’ and the ‘normative’. In one camp

was the real political science, claiming to deal scientifically with the

faxt> of political life as they are, and in the other was ‘theory’, confined

to the ivory tower of political philosophy and reflecting not on wh:

is but on what ought to be.

This bartex: division of the discipline undoubtedly owed much to

the culture of the Cold War. which generally encanraged the withdrawal

of academics from trenchant social criticism. At any rate, political

science lost much of its critical edge. Ihe object of study for this so-

called ‘science’ was not creative human action biir rather politieal

‘behaviour’, which could, it was claimed, be comprehended by quan-

titative methods appropnate to the involuntary motions of material

hodies, atoms or plants

This view of political science was certainly challenged by some

political theorists, notably Sheldon Wolin, whose Politics and Vision

elognently ascerted the importance of creative vision in political analysis?

But at least for a time, many political theorists seemed happy enough

2 Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innuation ie Western Plitial Thought wae

Fist published in 1960. The most recent expanded edition was published by Princeton

University Prov in 2006,

HE SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY 5

“behiw=

1 place assigned to them by the ultra-empiric

me dominant in US pitieal scence departments tscemed

souraiily congenial t0 the disciples of Leo Strauss, who formed an

sei tiance with the behavioural, each faction agreeing %

(het te iilety oF she otber' triton? Themis would

espe Cphilocophers in peace to spin thei intricate conceptual webs,

wee the normative’ theorists Would never cast a critical eye at their

wa taal caleagues political analysis. The Straussian attack on

sararcisy’ was directed against other theorists, in self-proclaimed

“fsoce of universal and absolute truths against the relativism of

ceernitys andy aldbvugh they would later emerge at influential

Mcalopuce of neoconservatism and as something like pailosophical

vents to the repime of George W. Bush Straussian political theorists

ti an easlier generation we on the whole content to pursue their

stecrirnnry and antimodernist (if not antidemocratic) political agenda

Co the philosophical plane ~ except when they ventured completely

Gutside the wails of the aualemy 10 write specches for right wing

trliviciane. Their ‘empiricist’ colleagues seem to have understood

Ghat Stranssians, with their esoteric, even cabaliste philosophical

provceupations, represeuted nu challenge wo the shallowness and vay

‘6f ‘empirical’ political science.

to accept the

4 tn is or che place to engage m the deta abu Lew Susu’ own puta

ews The ie heres hs approach othe dy of poli theory Born n Germany

1 185, Srase enigrted co x US in 1937 and epeialy alts his apontinent f0

thecal at the Uisersty of Chicago in 148 exerted at inuence on the sty

‘of political ec in North Aneta, reducing a school of interpretation which would

he tated on by bis ipl due cadets. The Strwecan=pproach ool

theery begins fom the premise that politcal plosophers, whe are concerned with

ory ofthe canon to daguse hc ides, inorder rx tobe perccued as suber

“They have therlore, aconding to Sraussans, acopted ah esene mode oF WH

thich obliges scholayincerctes to read between the lines. This compulsion, the

Seraussians seem wo guest, has bon agarvanel by the onset of modern ad

omtculty mass democracy which hater caer virtue they mayo may et hae)

2re inevitably dominated by opinion ar, appre host o uth and knowledge

Seransiane regard themselves a piieged heir acces to

the tre meaning of peli pilesonh, taking enormous ier of iterpeaion,

sich say Gout che eral est In way ew ter sclars would allow tema

This approach sends, needless £0 sy to lint the possibilities of debate between

‘sean and those ouside che fraternity sine exer interpretations of text can be

"ued ou a Priors blind o iden ‘sete’ meaings. However much Ssussians

fay have denigrated ‘empirica? political scence, their mathed has reinforced the

‘cosure of ‘normative’ pelitical theory in ite own elipite dora,

and enelive fe

6 CITIZENS TO LORDS

Yet Straussians were not alonein accepting the neat division between

At least,

there was a widespread view that grubbing around in the realities of

politics, while all right for some, was not what political theorists should

«lo, The groundbreaking work of the Canadian political theorist, C.B-

Macpherson, who had introduced a different approach to the study

of political theory by situating seventeenth-century English thinkers

in the historical context of what he ealled a ‘possessive market society",

proved to belittle more than a detour from the mainstream of Anglo-

American scholarship. Scholars who studied and taught the history

of political thought, the ‘classics? of the Western ‘Ganon’, did noc

always subscribe to the Straussian variety of anti-historicismy; but they

were often even more averse ro history. Many treated the ‘greats’ as

pure minds floating free above the political (ays and any attempt to

plant these thinkers on firm historical ground, any attempt to treat

them as living and breathing historical beings passionately engaged in

the politics of theit own time and plicc, would be dismissed as

tsivialization, demeaning great men and reducing them to mere publi-

cists, pamphleteers and propagandists.>

‘What distinguished teal political philosophy from simple ‘ideotogy",

according, to this view, was that it rose above political senagele and

partisanship. It tackled universal and perennial problems, secking

principles of social order and fhuman development valid for all human

beings in all times and places. The questions raised hy rue political

philosophers are it was argued, intrinsically ranshistorical: what does

iu meant to be truly human? What kind of society permits the full

development of that humanity? Whar are the viniversal principles of

right order for individuals and societies?

1k seems not to have occurred to proponents of this view that even

such “universal” questions cold he asked and anciwored in nye dl

served certain immediate political interests rather than others, ot that

‘hese questions and answers might even be intended as passionately

partisan. For instance, the human ideale np

tell us much about their social and political commitments and where

empirical and normative, or hetween theory and practi

4 The Political Theory of Posessive Individual: Hobbes to Locke, was published

by Oxfont University Press in 1962, but Macpherson had already published articles in

‘the 19508 applying hs contextual approach. Although Ihave disagreements with him

and regan his deal-sype ‘possessive market society” aka tather ahistorical abstraction,

there can hele denbs thar he broke impereant new grea

5 See, for insance, Dante Germino, Beyond Ideology: The Revival of Political

"Theory (New Yorks Harper and Reo 1967).

SHE SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY 7

and in the conficts of their day. The failure to acknuvledge

sea i fakes cholo ew lle benef in trying to understand

the dassics by situating them in their author's time and place. The

ee yextualization of political thought or the “sociology of knowledge

wight ell us something about the ideas and motivations of lesser

mrartale and ideologues, but it could tell us nothing worth knowing

Shout a great philosopher, a genius like Plato.

“This aliost naive abistoricism was bound to produce a reaction,

and a very different school of thought emerged, which has since over-

fuken its rivals. What has come to be called the Cambridge School

rats, at fest on the face of it, t0 go to the other extreme by radically

resting the works, great and small of poiial theory and denying

them any wider meaning beyond the very local moment of their

Creation. The must effective exponent of this approach, Quentin

Skinner, in the introduction to his classic text, The Foundations of

‘Modern Political Thought, gives an account of his method that seems

directly antithetival 1 the dichowomies on which the ahistorical

anprch was based against the sharp dsintion a polial

ilosophy and ideology and the facile opposition of ‘empirical’ to

reste nto anges Shinn meaner the hinory

of political theory by treating it essentially as the history of ideologies,

and this requires a detailed contextualization. ‘For Itakeit that political

life itself sexs the main problerss for the political theorist, causing a

certain range of issues to appear problematic, and a corresponding

range of questions to become the leading subjects of debate."*

“The principal benefit of chis approach, Skinner waites, is that it

equips us ‘with a way of gaining greater insight into its author's mean-

ing than we can ever hope to achieve simply from reading the text

itself “over and over again” as the exponents uf he “textuslist”

approach have charscteristically proposed.” But there is also another

advantage:

It will now he evidene why I wish to. maintain that. if the history

of political theory were to be written essentially as a history of

ideologies, one outcome might be 2 clearer understanding of the

links between political theory and practice. For it now appears that.

in recovering the terms of the normative vocabulary available ro any

6 Quentin Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Roluical Though, Volume I: The

enasance Carbide: Cambie Users Es 1978

8 CITIZENS TO LORDS

sven agent for the description of his political behaviour, we are at

the same rime indicating one of the constraints upon his behaviour

itself. This suggests that, in order to explain why such an agent acts

as he docs, we are bound to make some reference to this vocabulary,

since it evidently figures as one of the determinants of his action.

‘This in turn suggests that, if we were to focus our histories on the

study of these vocabularies, we might be able to illustrate the exact,

‘ays im which the explanation of political behaviour depends upon

the study of political thought.

Skinner then proceeded to constrict a history of Western political thought

in the Renaissance and the age of Reformation, especially the notion of

the state as it acquired its modern meaning, by exploring the political

vocabularies available to political dhinkers anal autor and the specific

sets of questions that history had put on their agenda. His main strategy.

here as elsewhere in his work, was to cast his net more widely than

historians of political thought have custouiatily done, considering noc

just the leading eheorists but, as he put it, ‘the more general social and

inxellectual matrix out of which their works arosc’.* He looked not only

at the work of tle greats bun also at snore ‘ephemeral contemporary

contributions to social and political thought’. as a means of gaining

access tothe available vocabularies and the prevailing assumptions about

political society that wete shaping debate in specific times and places

Skinner's approach has certain very clear strengths; and other

merabers of the Cambridge School have also applied these principles,

‘fica very effectively wv the analysis of specific thinkers or ‘traditions

of discourse’, especially those of early madern Fngland. The propo-

sition that the political questions addressed by political theorists,

judhuding the great ones, are thrown up by real political life and are

shaped by the historical condi

more nor less than good common sense.

‘Bur much depends on what the Cambridge School regards a8 rel

ans in which they arise coome handly

different meaning than might be inferred from Skinner's reference to

the ‘soctal and intellectual matrix’, It turns out that the ‘social’ matrix

has litle to do with ‘society’, the economy, or even the polity. The

social context is itself intellectual, or at least the ‘social’ is defined by,

and only by, existing vocabularies. ‘The ‘political life” that sets the

agenda for theory is essentially a language game. Inthe end, to contex-

Shad px

THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY 9

lize a ent isto situate it among other texts, among a range of

{walt janes, dacourses and ideological paradigms at various levels of

Pioeiliny from the dassis of political thought down to ephemeral

orm ox political speeches. What emerges from Skinner's assault on

farce nts othe att ary of tes et anther

Y reectaal history, yet anther history of ideas ~ certainly more

ead noes ohare than what went befor, but hardly

sortie a ale tox

“h catalogue of what is missing from Skinner's comprebensive history

of political ideas from 1300 to 1600 reveals quite starkly the limits of

re peomtets. Skinners dealing with a period masked by unajon sexi

and economic developments, which loomed very large in the theory

nd practice of European political thinkers and actors. Yet there is in

fas Look no substansve consideravion of syviuture, he atinicacy

and pessantey, land distribution and tenure, the social division of

Tabour, social protest and conflict, population, urbanization, trade,

commerce, manufacture, and the burgher class”

It ig tne that the other major founding figure of the Cambridge

School, J.G.A. Pocock, is, on the face of it, more interested in economic

developments and what appear tobe mateial factors like che discovery”

fin Peendles words of eapitaland the emergence nf commercial society"

in eighteenth-century Britain. Yet his account of this ‘sudden and

traumatic discovery’ 1s, its way, even more divorced from historical

processes than Skinnerc acerunt af the state The critical mament

for Pocock is the foundation of the Bank of England, which, he argues,

trough about a complete transformation of propery, the transforma

tion ofits stmecture and morality, with ‘spectaenar abruptnece’ in the

‘mid-1690s; and it was accompanied by suéden changes in the psychology

of poles. But in this argument, the Bank of tngland, and indeed

corametcial society. seem tn have nn histrry at all "They elderly

‘emerge full-grown, as if the transformations of property and social

‘slaiony in tbe sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and the formation

OF English agrarian «apitaicm, ar the

oystem associated with the development of capitalist property which

Preceded the foundation ofthe national bank, had no Fearing on theit

Consolidation in the cnmmercal capitalism ofthe eighteenth cont

aling

ly Englich

9 See Neal Wood, john Locke and Agrarian Capitalism (Berkeley ad Los Angeles:

University of California Press, 1984) p 1.

10 1G.A. Pocock, Virtue, Commerce, and History (Cambridge: Cambridge

awersity Press, 1983), p 168, An elaboration of this argument en Pocock and

ommercal sociey will have te anaic anther wl dew wae selva pes

x0 CITIZENS TO LORDS

Such a strikingly ahistorical account is possible only because, for

Pocock perhaps even more than for Skinner, history has little to do

with social processes, and historical transformations are manifest only

48 visible shifts in the languages of politics. Changes in discourse that

represent thee

are presented as its origin and cause.

So, what purports to be the history of political thought, for both

Pocock and Skinner, is curiously shistorical, not only in its failure

to grapple with what on any reckoning were decisive historical devel-

‘opments in the relevant periods but also in its lack of process.

Characteristically, history for the Cambridge School is a series of

disconnected, very local and particular episodes, such as specific

political controversies in specific times and places, which have no

apparent relation to more inclusive social developments o& to any

historical process, large or small."

This emphasis on the local and particular does not, however,

prechide consideration of larger spans of tine and space. The “adi-

tions of discourse’ that are the stuff of the Cambridge School embrace

long periods, sometimes whole centuries or even more. A tradition

may cross national boundaties aid evens continents. Icaay bet pustiee

ular literary genre fairly limited in time and geographic scope, like the

‘mirror-for-princes’ literature, which Skinner very effectively explores

to analyze the work of Machiavelli; ot uotably in the case of John

Pocock, it may be the discourse of ‘commercial society’ which char-

acterized the cighteenth century, or the tradition of ‘civic humanism’,

and a wider scope. Bue whatever its duration

or spatial reach, the tradition of discourse plays a role in analyzing

political theory hardly different from the role played by particular

episodes (which are themselves an interplay of discourses), like the

Engagement Controversy in which Skinner simates Hobbes, or the

Exclusion Crisis which others have invoked in the analysis of Locke.

in both cases, contexts are texts; and at neither end of the Cambridge

historical spectrum. from the very local episode to the lang and wide

spread tradition of discourse, do we see any sign of historical move

ment, any sense of the dynamic connection between one historical

moment and another or between the politieal episode and the social

Imination and consolidation of a social transformation

whiels had a longer

11 For a critica discusion of Skinner's ‘atomized and ‘epsodic™ aeatment of

history. see Cary Nederman.*Quencin Skinner’ State: Historical Method and Traditions

of Discourse’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 18, No.2, June 1985, pp.

haas2

THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY um

at underhe it. In effec, long historical provesses ate thea

a is money bell episodes :

sels co eption of history, the Cambridge Schoo! has somethin

Ins concn oy sore ‘powroderis’ tends

Disco tory dissolved into contingeney Both respond co ‘grand

Ms ard Shnot by criially examining their virtues and vices but by

Faanding bstorical processes altogether

The Social History of Political Theory

1 ‘social history of political theory’, which is the subject of this

Wes uats from the premise thatthe great political thinkers ofthe

pase wae passivnatcly engaged in the issues of their rime and place.

"This was so even when they addressed these issues from an clevated

philosophical vantage point, in conversation with otler philosophers

fn viber times arnd places, and ever, oF especially, when they sought

to translate their reflections into universal ard timeless principles. Often

their engagements took the form of partisan adherence to a specific

and wlentifiable political cause, ot even fairly transparent expressions

of particular interests, the interests of a particular party or class. But

their ideological commitments could also be expressed in a larger

Vision of the good soviety and human ideals.

Ar the same time, the sreat political thinkers ate not party hacks

or propagandists Political theory is certainly an exercise in persuasion,

but its tools are reasoned discourse and arguunentation, in @ genuine

search for some kind of truth. Yer if the ‘preats? are different from

lesser political thinkers and actors, they are no less human and no less

steeped in history. When Plato explored the concept of justice in the

Republic, or when he outlined the different levels of knowledge, he

was certainly opening large philosophical questions and he was

tions, no less than his answers, were (as I shall argue in a subseauent

chapter) driven by his critical engagement with Athenéan democracy.

To acknowledge the humanity and historic engagement of political

thinkers is surely not to demean them or deny them their greatness

Im any case, without subjecting ideas to eritical historical scruting, it

12 Fora discussion of the term social story of political thecre’ see Neal Wood,

“The Susi History of Political Theory, Foitical Theory, Vol. 6 No. 3, Agus 1978,

Hiigtra om ” Agu

nm CITIZENS TO LORDS

{5 impossible to assess their claims to universality or transcendent

truth, The intention here is certainly to explore the ideas of the most

important political thinkers; but these thinkers will always be treated

as living and engaged human beings, immersed not only in the rich

intellectual heritage of received ideas bequeathed by their philosophical

predecessors, nor simply against the background of the available vocab-

tlaries specific to their time and place, bat also in the context of the

social and politieal processes that shaped their immediate world.

‘This social history of political theory, in its conception of historical

‘contexts, proceeds from certain fundamental premises, which belong to

the wadition of ‘historical matesialisn?: huinan beings enter inte tclations

with each other and with nature to guarantee their own survival and

social reproduction. To understand the social practices and cultural

products of any Gite and place, we Heed to know something about those

conditions of survival and social reproduction, something. abour the

specific ways in which people gain access to the material conditions of

life, about how some people gain access tw the labour of others, about

the relations between people who produce and those who appropriate

what others produce, about the forms of property that emerge from

these social relations, and about how these relations are expressed in

political domination, as well as resistance and strueele.

This is certainly not to say that a theorist’ ideas can be predicted

or ‘read off" from his or her social position or ciass. The point is

simply that the questions confronting any political thinker, however

eternal and universal those questions may seem, are posed to them in

specific historical forms. The Cambridge School agrees that, 1n order

to understand the answers offered hy political thee

something about the questions they are trying to answer and that

different historical settings pose different sets of questions. But, tor

the social history of political theory, these qnestinne are peed nat

only by explicit political controversies, and not only at the level of

Philosophy or high politics, but also by the soctal pressures and tensions

thar shape human interactions cnteide the political arena and heynndl

the world of texts.

This approach differs from that of the Cambridge School both in

the scope of what is regarded as a ‘context’ and in the effort to appre

hend historical processes. Ideological episodes like the Engagement

Controversy or the Exclusion Crisis may tell us something about

thinker like Hobbes or Locke; but unless we explore how these thinkers

situated themselves in the larger historical processes that were shaping

their word, itis hard to see how we are to distinguish the great theorists

from ephemeral publicists.

6, we must kien

quip SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY B

Long-term developments in socal relations, property forms and

see etries: and itis undoubtedly true that political theory tends to

Fen h ar moments like this, when history intnades most dramatically

aor Gialouue among rexts or traditions of discourse. But a major

so ike John Locke, while he was certainy responding to specific

“indomentary political controversies, was raising larger fundamental

anecrons about sexial relation’, property and the cate generated by

iMger social transformations and structural tensions ~ in particular

eulopments that we associate with the ‘rise of capitalism. Locke

id nets needless to sa) know that he was obseéving she development

Sf what we cal capitalism but he was dealing with problems posed

by is characteristic transformations of property, cass relations and

thestate, Io divorce hin (round

hic wrk and its capacity to illuminate its own historical moment, lt

alone the ‘human condition’ in genera.

Tr different historical experiences yive rive to different sets uf probe

lem, it follows that these divergences will also be observable in vari-

tus “traditions of discourse’ Its not, for instance, enough to talk

bout a Western or European historical experience, defined by x

common cultueal and philosophical inheritance. We must also look

‘or differences among the various patterns of property relations and

the various processes of state-formation that distinguished one

European society from another and produced different patterns of

theoretical interrogation, different sets of questions for political

Uhinkers 0 address

The diversity of “diseanrsee’ does nar simply express personal or

ven national idiosyncrasies of intellectual style among political

philosophers engaged in dialogue with one another across geographical

and chronological henndarie. Ta the eviens thar plitieal philosophers

are indeed reflecting not only epon philosophical traditions but upon

mubiems set by political lie, their “discourses are diverse mn large

Part because the paliical penhieme thry reanfronr ane diserce “The

Boblem ofthe state for instance, has presented ill historically in

diferent gues even to sch cose neighbour as the English and the

Even the ‘perennial questions’ have appeared in various shapes. What

appears as a salient issue will vary according to the nature of the

larger sunial wuntentis to impoverish

/ave discussed these differences at some length in The Pristine Culture of Capi-

‘alsm: A Historical Pasay on Old Regimes and Modern States (Leatoes Verso 1993).

1 CITIZENS 10 LOKDS

principal contenders, the competing social forces at work, the contflict-

ing interests at stake. The configuration of problems arising from a

struggle such as the one in early modern England betwern ‘improxing?

landlords and commoners dependent on the preservation of common

and waste land will differ from those at issue in France amiong peasants,

scigncurs, and a tax hungry state. Even within the same historical or

national configuration, what appears as a problem to the commoner

or peasant will not necessarily appear so to the gentleman-tarmer, the

seigneur, or the royal office-holder. We need not reduce the great

political thinkers to ‘prize-fighters’ for this or that social interest in

order co acknowledge the importance of identifying the particular

constellation of problems that history has presented to them, ot to

recognize that the “dialogue’ in which they are engaged is not simply

a timeless debate with rootless philosophers but an engagement with

living historical accots, Luth those who dominate and those who resist.

“To say this is not to claim that political theorists from another time

and place have nothing to say to our own. There is no inverse relation

berween historical contextualization and ‘relevance’. On the const

historical contextualization isan essential condition for learning from

the ‘classics’, not simply because it allows a better understanding of

a thinker’s meaning and intention, but also because itis in Hie content

‘of history thar theory emerges from the realm of pure abstraction and

centers the world of human practice and social interaction.

I here are, of course, commonalities of experience we share with wut

oman, and there are innumerable

practices learned by humanity over the centuries in which we engage as

car ancestors did. Uhese common experiences mean thar much of what

reat chinkers of the past have to say is readily accessible to us. Bat if

the dassics of political theory are to yield fruitful lessons, it snot enough

to acknowledge these commonalities of human and historical experience

for ta mine the claesice fir certain ahstract winiversal principles. To

historicize is to humanize, and to detach ideas from their own material

and practical setting is to lose our pomts of human contact with them.

“There is a way, all roo common, of studying the history of political

theory which detaches it from the urgent human issues to which itis

addressed. To think about the politics in political theory is, atthe very

least, to consider and make judgments about whar ir would mean £©

translate particular principles into actual social relationships and

political arrangements. If one of the functions of political theory 18

fo sherpen our perceptions and conceptual instruments for thinking

about politics in our own time and place, that purpose is defeated by

emptying historical political theories of their own political meaning.

predecesears jnst hy irre of bei

THE SOLIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY ts

for instance, I encountered an argument about

rem USheory of natural slavery, which scomed to me to illustrate

Aen Morrcomings of an ahistorical approach.!* We should not, che

the ent went, ucat the theory of natural slavery as a comment on

aepually actual social condition, the celation berween slaves and

saaege as it existed in rhe ancient world, because to do so isto deprive

sre any significance beyond the socio-economic circumstances of its

ict ay ce naads we shoul recognize ie ay x plilosophical

Rretaphor for the unwversal human condition in the abstract. Yet to

“Tony that Aristotle was defending a ral social practice, the enslavement

of real human beings, of fo suggest that we have more to learn about

the human condition by refusing to confront his theory of slavery in

it concrete historical meaning, seems 2 peculiar way of sensitizing us

to the realities of social life and polities, or indeed the human condition,

Some yeats ABs

in uur own time oF any’ other.

‘There is also another way in which the contextual analysis of political

few of MU. Finley Ancient Savery and Modern

14 Arle Seresbouses in

cology, writes dsmissively of is approach asa ‘soca! historian, which, apparent

car eel us fev unsurprising chings at dre peinpitan of writers om slavery

fut cannot illuminate the deeper meaning of philosophical reflections sus as those

* ‘riote, ‘Aristotle’ ellestions on the nature of slavery she wrtes, more us beyond

patticular slave and @ particular master. Instead, te slave's subordination co the

imsster refects our own subordination to katie. Slavery is nor only the degraded

Fe inen of one witheur camel or hy or her akewe Tr iethe conn ofall humans

‘ature. The master and the lve & not tlaionship lite tothe lve

ofthe anion and ender wold wih Ts

aeferconal stats which Arneleexortsus vo understand so tt we ma understand

sn in soca wn tr he a yn

tation © the species ofa time and place, and sae i why though he notes the

‘Stores of A uy of Astana ate syd he ot

inthe elevanc of encientslaers For hat we must rrntothe ancient cilosopher

lite Teas Wal. 9)No, Nees p79) eure has Ane

-zems perc to deny that he iyi the proces efeting on the very specific

sth of slvery ave kn ta de Geckos Wh psp be poe

ey that Arcot intends to si slavery By teatngit asa manfettion of hora

shoals tbortinaion ro nature (though we may be acne, on the conte,

nk har ths naturalization of slaves sens precy orsiaton. Bu here i

27 3. sorathing rather walling abow the view that s‘Blosophea erp

eof Arto, which detaches i cnn of avery Fo the concrete el ies

r aster-sLye lation in trial tne and apace, telly x tore about “the

LADS of anes fined Arde vows about than dove me

al history’, which eas the philosophers reflections a6 pei, recctons O0

"ens nota a metaphor hut ata all oosoncree historia reais

sf The mactr apd slave

16 CITIZENS TO LORDS

theory can illuminate our own historieal moment. If we abstract a

political theory from its historical context, we in effece assimilate it

to our own. Understanding a theory historically allows us to look at

‘our own historical condition from a eritieal distance, from the vantage

point of other times and other ideas. It also allows us to observe how

certain assumptions, which we may now accept uncritically, came into

being and how they were challenged in their formative years. Reading

political theory in this way, we may be less tempted to take for granted

the dominant ideas and assumptions of our own time and place.

Thisbenefit may nut besv readily available ew contextual approaches

in which historical processes are replaced by disconnected episodes

and traditions of discourse. The Cambridge mode of contextualization

canewages us tu believe that the old political chinkers have litte to

say in our own time and place. It invites us to think that there is

nothing to learn from them, because their historical experiences have

suo apparent connection to Our own. To discover what there i to learn

from the history of political theory requires us ta place ourselves on

the continuum of history, where we are joined to our predecessors not

uiily by the continuities we share bur by the processes of change that

intervene between us. bringing us from there to here

‘The intention of this stud, then, is not only to illuminate some

classic texts and the conditions in which they were created but also to

explain by example a distinctive appenach to contextual interpretation

Tes subject matter will be not only texts, nor discursive paradigms, but

the social relations that made them possible and posed the particular

questions addressed by political thearists. This kind of contextual

reading also requires us to do something more than follow the line of

descent from one political thinker to the next. It invites us to explore

haw certain fundamental cacial relations ext dhe para

«creativity, not only in political theory but in other modes of discourse

that form part of the historical setting and the cultural climate within

which political :

Roman law or Christian theology:

While 1 try to strike a balance between contextual analysis and

interpretation of the major texte, some readere may think that this

way of proceeding places too much emphasis on grand structural

themes at the expense of a more exhaustive textual reading. But the

approach being proposed in this book: is best understood not as if

any way excluding or slighting close textual analysis bur, on the

Contrary as a way Of shedding light on texts, which others can put to

the test by more minute and detailed reading.

THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY 7

‘The Origin of Political Theory

scholars have offered various explanations for the emergence of political

theory in ancient Greece. There will be more in the next chapter about

the specific historical conditions that produced, especially in Athens,

the kind of confidence m human agency that s'a necessary condition

Uf political theory: In this chapter, we shall confine ourselves to the

general conditions that marked the Greeks out from other ancient

civilizations and set the agenda for political theory

The most vital factor undoubtedly was che development, perhaps

by the late eighth century BC, of the unique Greek state, the polis,

which sometimes evolved into self-governing democracies, as in Athens,

{rum the carly fifth to the late fourth century. This type of state differed

shaeply from the large imperial states that characterized other ‘high’

civilizations, and from states that preceded the polis in Greece, the

Minoan and Myeenean kingdoms. In place of an clakorarc burcauctatic

apparatus, the polis was characterized by a faidly simple stare admin-

istration (if we can even call it a ‘state’ at all) and a self-governing

civic community, in which the principal political tclations were not

between rulers and subjects but among, citizens ~ whether the citizen

body was more inclusive, as én Athenian democracy, or less 50, a8 in

‘Sparta or the city states of Crete, Politics, in Ue seuse we have cone

10 understand the word, implying contestation and debate among

diverse interests, replaced rule or administration as the principal object

of political dicourse, These factors were, uf vourse, more prouuinent

in democracies, and Athens in particular, than in the oligarchic polis.

43s also significane that by the end of the fifth century, Greece was

becoming a literate culture, in unprecedented ways and to an unprece-

vel deze. Although we should not overestimate its extent. a kind

{ Popular literacy, especially in the democracy, replaced what some

ed ee cn eee ee ee ee

fe litcsaxy in which reading and writing were

{Pectslized skills practised only oF largely, by professionals or scribes

happened in Greece, and especially in Athens, has been described

S the democratization of writing,

of poPtlar rule, which required widespread and searching discussion

ret osing social and political issues, and which provided new oppor.

ons for political leadership and influence, when coupled with

te ichinn Prosperity, broughe an increasing demand for schooling and

ith a & An economically vital, democratic and relatively free culture

and antici means of written expression and exact argumentation,

Noursble rane audience for such discourse, created an atmosphere

‘othe bicth and early thriving of political theory, a powerful

x8 cIrIzeNs TO LORDS

and ingenious mode of self-examination and reflection that continues

to the presenc.

But we need to look more closely at the polis. and especially the

democracy, to understand why this new mode of political thinking

100k the form that it did, and why it raised certain kinds of questions

that had not been raised before, which would thereafter set the agenda

for the long tradition of Western political theory. There will be more

in the next chapter about Athenian society and politics, as the specific

context in which the Greek classics were written. For oir purposes

here, a few general points need to be highlighted about the conditions

1m which political theory originated.

The polis represented not only a distinctive political form but a

tunique organization of social relations. The state in other high

‘avilizations typically embodied a relation between rulers and subjects

that was at the same rime a relation berween appropriators and

ptoducers. The Chinese philosopher, Mencius, once wrote that ‘Those

‘who are ruled produce food; those who rule are fed. That this is right

is universally recognized everywhere under Heaven.’ This principle

nicely sums up the essence of the relation between rulers and producers

which characterized the most advanced ancient civilizations.

In these ancient states, there was a sharp demarcation between

production and politics, in the sense that direct producers had no

political role, as rulers or even as citizens. The state was organized 10

control subject labous, and it was above all through the state that some

people appropriated the labour of others or its products. Office in the

state was likely to be the primary means of acquiring great wealth.

Even where private property in land vias faily well developed, state

office was likely to be the source of large property, while small property

generally carried with it obligations to the state in the form of tax,

throughout its long imperial history that large property and great

wealth were associated with office, and the imperial state did everything

toimpede the autonomous development of powerful propertied classes.

‘The ancient ‘bureaucratic” state, then, constituted a ruling body

superimposed upon and appropriating, from subject comuunities of

direct producers, above all peasants. Although such a form had existed

in Greece, both there and in Rome a new form of political organization

emerged which combined landlords and peasants in one civic and

military community. While others. notably the Phoenicians and

Carthaginians, may have lived in city-states in some ways comparable

to the Greek polis or the Roman Republic, the very idea of a civie

JHE SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICA THEORY 9

snunity and ctizenshiy as sin from the princi of rule by

com sll

cetiperimposed state apparatus, derive from the Greck

bay -a of a peasant-citizen was even further removed from the

experience of uther ancient states. The role of slivery in Greece and

Reune will be discussed in subsequent chapters; but, for the moment,

itisimportant to acknossledge the distinctive political role of producing

iteses peasants and craftsmen, and their unique relation to the state.

fe the Greck polis and the Roman Republic, appropriators and

producers in the citizen body confronted one another directly as

Midividnals and as classes, as landlords and peasants, ot primtatily as

fulers and subjects. Private property developed more autonomously

find completely, separating itself more thoroughly from the state. A

new and distinctive dynamic of property and class relations was difer~

catiated ont from the traditional relations of (appropriating) state and

(producing) subjects.

{he special characteristics of these states are reflected in the classics

of ancient political thought. When Plato, for example. attacked the

democratic polis of Athens, he did so by opposing to it a state-form

that departed radically from precisely those features most unique and

specific ta the Greek polis and which hore a striking resemblance in

principle to certain non-Greek states. In the Republic, Plato proposes

2 community of rulers superimposed upon a ruled community of

Deodhicers, primarily peasants, a state in which producers are individ

ually “free? and in possession of property, not dependent on wealthier

Prwvate proprietors; but, although the rulers own no private property

Producers are collectively subject to. the ruling. comm

compelled to transfer surplus labour to their non-produeing, masters.

Poliseal and military functions belong exclusively to the ruling clas,

according tn she radisinnal separatian af mikvary and farming lace,

which Plato and Aristotle both admired. In other words, those who are

‘isd proguce tod, and those who rule are fed. Plato no douibt drew

inspiration from the C: . these

Principles ~ notably Sparta and the city-states of Crete; but itis likely

that the model he had more specifically in mind was Egypt — of, at

ease, Egypt as the Greeks, sometimes inaccurately, understood it.

ag thet classical writers defended the supremacy of the dominant

lasses i less radical and more specifically Greco-Roman ways. In partic-

tla, the doctrine of the ‘minced constitution’ ~ which appeate in Plato's

Cauts 204 figures prominently in the writings of Aristotle, Polybius, and

Packie, Zests @ uniquely Greek and Roman reality and the special

lems faced by a dominane class of private proprietors in a state

and

y

Le exarae

20 eran

that incorporates rich and poor, appropriators and producers, landlonds

and peasants, into a single civic and suilitary comnuunity. The idea of

the mixed constitution proceeded from the Greco-Roman classification

of constitutions — in particular, the distinction ‘among government by

the many, the few, or only one: democracy, oligarchy, monarchy. A

constitution could be ‘mixed’ in the sense that it adopted certain

clements of each. More particularly, rich and poor could be respectively

represented by “oligarchic’ and ‘democratic’ elements; and the predom-

inance of the rich could be achieved nor by drawing a dear and rigid

division between 2 ruling apparatus and subject producers, or between

rmuhtary and tarmung classes, but by tilting the constitutional balance

towards oligarchic elements.

In both theory and practice, then, a specific dynamic of property and

lass relations, distinct trom the relations between rulers and subjects,

swas woven directly into the fabric of Greek and Roman politics. These

relations generated a distinctive array of practical problems and theo-

retical issues, especially in the democratic polis. There were, of course,

distinetive problems of a society like Athens, chat lacked

an unequivocally dominant ruling stratum whose economic power and

political supremacy were coextensive and inseparable, a society where

economic and political hierarchies did not coincide and political

relations were less between rulers and subjects than amiong citizens.

‘These political relations were played out in assemblies and juries, in

constant debate, which demanded new rhetorical skills and modes of

argumentation. Nothing could be taken for granteds and, not surpris-

ingly, this was a highly litigious society, in which political discourse

derived much of its method and substance from legal disputation, with

all its predilection for hairsplitting, controversy.

Greek political theorists were self-conscious about the uniqueness

order

is apenifi fons uf state, and they inevitably caplored th

of the polis and what distinguished it from others. They raised questions

about the origin and purpose of the state. Having effectively invented

st new idcininy ce civic idemity of citizensbipy hey pored yu

about the meaning. of citizenship, who should enjoy political rights

and whether any division between rulers and ruled existed by nature.

‘They confronted the tension between the levelling identity of citizenship

and the hierarchical principles of noble birth or wealth, Questions

about law and the rule of law; about the difference between political

organization based on violence or coe

based on deliberation or persuasion; about human nature and its

suitability (or otherwise) for political life ~all of these questions were

thrown up by the everyday realities of life in the polis

1 aud civic community

rie SOCIAY HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY ar

inthe absence of aruling ass whose ethical standards were accepted

no asstime the eternity and inviolablity of traditional norms.

mesure i a lg

arcing old proverbs or reiting epics of aristocrat hero-kings but

ePSGnsracting theoretical aepuments to meer theoretical challenges

Gystons arose abou che origin of moral and politcal principles and

oeetmakes them binding. From the same political realities emerged

he humanistic principle that ‘man is the measure of all things’, with

ii che new questions that this principle entailed. So, for instance, the

Sophists (Greek philosophers and teachers ssho will be discussed in

the next chapte) asked whether moral and politcal principles exist

ature or merely Ly custo ~ 4 question that could be a

2 tone wave. some congenial to democracy, others in support of

Gligarchy; and when Plato expressed his opposition to democracy,

he could not rely on invokinn, the gos o1 time-honoured custom but

seas obliged co make his case by means of philosophic reason, to

construct a definition of justice and the good life that seemed to rule

‘out democracy.

Political Theory in History: An Overview

Born in the polis. this new mode of political thought would survive

the polis and continue to set the thearctical agenda in later centuries,

when very dilerene forts of stace prevailed, This longevity hay not

been simply a matter of tenacious intellectual legacies. The Western

tradition of political theory has developed on the foundations estab-

lished in ancient Greece because certain issues bave resained at the

‘entre of European political life. In varying forms. the autonomy of

Private property its relative independence from the state, and the

fon tenes hee fc! of social power have continued to shape

the political azenda. On the one hand. appropriating classes have

ne ded the state to maintain order, conditions for appropriation and

ottel over producing classes. On the other hand, they have found

i ae @ burdensome nuisance and a competiter for surplus labour.

bani ® wary eye on the stare, the dominant appropriating classes

ee always had cw curn their attention to their relations with subor-

tampa ptodlucing, classes. Indeed, their need for the state has been

mea ectermined by those difficult relations. n particular, throughout

matt of Western hiscory, peasants fed, clothed, and housed the lordly

rity by means of surplus labour extracted by payment of rents,

22 CITIZENS TO LORDS

fees, or tributes. Yet, though the aristocratic state depended on peasants

and though lords were always alive to rhe threat of resistance, the

politically voiceless classes play little overt role in the classics of Western

political theory. Their silent presence tends to be visible only in the

great thenrerical efforts dewoted to justifying social and political hier

archies.

the relation between appropriating and producing classes was to

change fundamentally with the advent of capitaliem, but the history

‘of Western political theory continued to be in large part the history of

tensions between property and state, appropriators and producers. In

general, the Western tradition of political chcory has becn ‘history

from above’, essentially reflection on the existing state and the need

for its preservation or change written from the perspective of a member

or client of the ruling classes. Yee it should be obvious that this history

from above’ cannot be understood without relating it to what can be

learned about the ‘history from below’. The complex three-way relation

betwicen the state, propertied classes and prunlusess, perhaps more

anything else, sets the Western political tradition apart from others.

There is nothing unique to the West, of course, about socities in

which dominant groups apptopriate what others produce. But there

is something distinctive about the ways in which the tensions betiseen

them have shaped political life and theory in the West. This may be

precisely because the relations bewween appropriators ané producers

have never, since classical antiquity, been synonymous with the relation

between rulers and subjects. To be sure, the peasant-citizen would not

survive the Rovian Euipire, and many centuries would pass before

anything comparable to the ancient Athenian idea of democratic

Citizenship would re-emerge in Europe. Feudal and early modern Europe

would, in its own way, even approximate the old division between

rulers and producers. as labouring classes were exclided from active

political rights and the power to appropriate was typically associated

wich the possession of ‘extra-economic” power, poitticai, yudiciai or

military. But even then. the relation herween tuilere and produirere was

never unambiguous, because appropriating classes confronted theit

abouring compatriots not, in the first instance, as a collective power

omwanized in the state but in a more ditectly personal relarion as

individual proprietors, in rivalry with other proprietors and even with

the state,

‘The auronomy of property and the contradictory relations between

ruling class and state meant that propertied classes in the West always

had to fight on two fronts. While they would have happily subscribed

to Menciuss principle abour those who rule and those who feed ther,

1 HISTORY OF POLITICAL THEORY ess

THe soc

take for granted such a neat division between rulers:

they could never Tatse there was a much clearer division than existed

‘and producers b

Trwhere hetwcen property and state,

he foundations of Western political theory established

Fie is eaten aa

ve aneiipeen many changes and additions to its theoretical agenda, in

ccping with changing historical conditions, which will be explored

tei following chapeers. The Romans, perhaps because their arieto-

Cove repli didnot confront challenge these of the Athenian

Cnocracy. did not produce a tradition of political theory as fruitful

eee een OA

Jnnovations, especially the Roman law, which would have major imph

tions for the development of political theory. The empire also gave

Fhe te Chrishanity, which becane the imperial religion, with all ies

euleural consequences.

Tes particularly significant thar the Romans began to delineate a

sharp distinction between public and private, even, petTapsy between

state and society. Ahene all, the opposition between property and state

as two distinct foci of power, which has been a constant theme through-

out the history of Western political theory, was for the first tine

Formally acknowledged hy the Romans in their distinction between

imperium and dominivm, power conceived as the right to command

and power in the form of ownership. This did nor preclude the view

expressed already hy Cicero in On Duties (De Offictis) — that the

purpose of the state was to protect private property or the conviction

that the state came into being. for that reason. On the contrary the

partnership of state and private property, which wentld continue to be

ventral theme of Western political theory, presupposes the separation,

snd che tensions, berween them.

‘Thetension herwern these ran farmenf penser, which was intensified

in theory and practice as republic gave way to empire, would, as we

wll se, piay a farge part in the tall of the Koman kmpire. With the

the of feudalism, that rencinn wae rrenloed an the side nf demininon,

8 the stare was virtually dissolved into individual property. In contrast

to the ancient division between rulers and producers, in which the

state was the dominant inst

iment of appropriation, the feudal seare

‘eurcely had an autonomous existence apart from the hierarchical chain

4 individual, if conditional, property and personal lordship. Instead

of @ centralized public authority, the feudal stare war a network of

Darcellized sovereignties’, governed by a complex hierarchy of social

“ations and competing jurisdictions, in the hands not only of lores

and kings, but als of various autonomous corporations, to say nothing,

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5811)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Maarten Van Ginderachter, Marnix Beyen - Nationhood From Below - Europe in The Long Nineteenth Century-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2012)Document273 pagesMaarten Van Ginderachter, Marnix Beyen - Nationhood From Below - Europe in The Long Nineteenth Century-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2012)Roc SolàNo ratings yet

- Erika Harris - Nationalism - Theories and Cases-Edinburgh University Press (2009)Document225 pagesErika Harris - Nationalism - Theories and Cases-Edinburgh University Press (2009)Roc SolàNo ratings yet

- Patrick J. Geary - The Myth of Nations - The Medieval Origins of Europe-Princeton University Press (2002)Document223 pagesPatrick J. Geary - The Myth of Nations - The Medieval Origins of Europe-Princeton University Press (2002)Roc Solà100% (1)

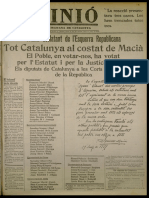

- Opinio L 19310630Document8 pagesOpinio L 19310630Roc SolàNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press International Labor and Working-Class, IncDocument16 pagesCambridge University Press International Labor and Working-Class, IncRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- Archilés - El Discreto Encanto Del Centralismo o Los Límites de La Diversidad en La España ContemporáneaDocument39 pagesArchilés - El Discreto Encanto Del Centralismo o Los Límites de La Diversidad en La España ContemporáneaRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- (The Wiles Lectures) Adrian Hastings - The Construction of Nationhood - Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism-Cambridge University Press (1997)Document247 pages(The Wiles Lectures) Adrian Hastings - The Construction of Nationhood - Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism-Cambridge University Press (1997)Roc SolàNo ratings yet

- Pi - Margall Pensamiento SocialDocument180 pagesPi - Margall Pensamiento SocialRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- Pi - Margall Pensamiento SocialDocument180 pagesPi - Margall Pensamiento SocialRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- La Catalunya Populista, Ucelay-Da CalDocument20 pagesLa Catalunya Populista, Ucelay-Da CalRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- Gabriel Alomar Sobre Liberalisme I NacioDocument72 pagesGabriel Alomar Sobre Liberalisme I NacioRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- CF LesNacionalitatsDocument744 pagesCF LesNacionalitatsRoc Solà100% (1)

- El Bombardeo de Barcelona Por El General Espartero 1842Document12 pagesEl Bombardeo de Barcelona Por El General Espartero 1842Roc SolàNo ratings yet

- El Republicanisme Lerrouxista A Catalunya (1901-1923)Document130 pagesEl Republicanisme Lerrouxista A Catalunya (1901-1923)Roc SolàNo ratings yet

- Fabregas Finances Revolucio Ok Amb Biografia PDFDocument189 pagesFabregas Finances Revolucio Ok Amb Biografia PDFRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- Fabregas Finances Revolucio Ok Amb Biografia PDFDocument189 pagesFabregas Finances Revolucio Ok Amb Biografia PDFRoc SolàNo ratings yet

- Fabregas Finances Revolucio Ok Amb Biografia PDFDocument189 pagesFabregas Finances Revolucio Ok Amb Biografia PDFRoc SolàNo ratings yet