Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Somatic Resources - SensorimotorPsychotherapy Approach To StabilisingArousal in Child and Family Treatment

Uploaded by

ana_vio_94Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Somatic Resources - SensorimotorPsychotherapy Approach To StabilisingArousal in Child and Family Treatment

Uploaded by

ana_vio_94Copyright:

Available Formats

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy 2017, 38, 573–581

doi: 10.1002/anzf.1270

Somatic Resources: Sensorimotor

Psychotherapy Approach to Stabilising

Arousal in Child and Family Treatment

Rochelle Sharpe Lohrasbe1,2 and Pat Ogden2

1

Private Practice, Victoria, BC, Canada

2

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute, Broomfield

Trauma first and foremost disrupts the normal functioning of the nervous system, leading to extremes of auto-

nomic arousal that often does not return to baseline once traumatic events are over. Dysregulation of arousal is a

common feature in relational trauma. Such dysregulation is present for the individuals and for the family unit.

When carers are dysregulated their capacities to cope with the challenges of caregiving are compromised. In turn,

children are left to manage not only their own dysregulation but also the fluctuations occurring in their carers.

Somatic resources and the embodiment of non-somatic relational resources are efficient for physiological arousal

and emotional regulation. Sensorimotor psychotherapy offers a means to better understand arousal and dysregu-

lation as well as employ effective strategies to stabilise children and carers in challenged families. This article will

provide a sensorimotor psychotherapy framework that can help in identifying priorities for therapeutic stabilisa-

tion efforts for children with abuse and/or neglect histories and their family members. The authors will discuss

the value of employing somatic resources in preference to other categories of resources, and suggest practical

ways in which to convert any non-somatic resource into a more embodied experience.

Keywords: sensorimotor psychotherapy, attachment, trauma, dysregulation, arousal, family therapy

Key Points

1 Dysregulated autonomic nervous system arousal is a common feature in relational trauma.

2 Dysregulated arousal impacts the capacities of carers to meet the safety and emotional developmental

needs of children.

3 Sensorimotor psychotherapy using Ogden’s Modulation Model offers a conceptual framework which is

helpful for working with dysregulated arousal and relational trauma.

4 The category of somatic resources is essential to stabilising dysregulated arousal.

Experiences in infancy and early childhood impact neurological, physical, emotional,

and cognitive development in children’s brains and bodies. When children are repeat-

edly frightened, neglected, mistreated, or violated in their homes or neighbourhoods

they endure chronic and prolonged periods of dysregulation, often alone and without

support or assistance. These children often fail to develop adequate arousal and affect

regulatory mechanisms, which leaves them with compromised social engagement,

proximity seeking, and either underdeveloped or hyper developed behaviours related

to their attempts to remain safe in dangerous circumstances (Stien & Kendall, 2004).

This results in a wide range of symptoms, reactions, and behaviours including failure

or delayed attainment of developmental milestones, challenges to negotiating social

interactions, and delays in walking, talking, and play. Repeated exposure to

Address for correspondence: rochelle@resilutions.com

ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy 573

Rochelle Sharpe Lohrasbe and Pat Ogden

inconsistent, absent, or frightening parental states of dysregulation elicit physiological

reactivity and influence the developing child, leading to ineffective-inefficient coping

strategies, as well as compromised physical, emotional, and relational functioning.

Disrupted and dysregulated patterns of elimination, sleep, nutritional, and

delayed language development affecting a range of expressive modalities can be seen

(Teicher et al., 2010). As these infants grow their ability to process information to

assess and evaluate their environment becomes compromised or distorted and tends

toward whole or partial stasis in survival patterns of arousal and defence, that is,

anxiety, anger, and apathy. Often these patterns either mimic the states of their car-

ers or present carers with challenges to soothing, needs meeting, safety, etc. Perpet-

ual states of anger, fear, panic – or the opposite: apathy, despair, and the flaccidity

that accompanies a ‘failure to thrive’ or giving up – mean the child must learn to

adapt to that carer for survival rather than the preferred situation where the carer

attunes to the needs of the child. The obvious inability of an infant to meet carer

expectations or emotional needs (i.e., the child doesn’t smile when the carer wants)

places the infant at risk for carer neglect, rejection, or even abuse if the caregiver is

angered.

Developmental limitations of language to communicate distress and need

Infants and toddlers are unable to use language to express or indicate their needs or

wishes. Since they are limited to cooing, crying, and other early vocalisations, their

carers, even well-resourced ones, can be challenged by confusion, misunderstanding,

and subsequent frustration in parent–child interactions. Carers who grew up in less

than optimal families and circumstances, when their own carers were challenged or

uninterested in meeting developmental needs, are doubly challenged as they must

now manage both their own arousal and dysregulation as well as their infant’s or

child’s. Distinguishing what kind of cry – hungry, frustrated, frightened, wet/soiled,

etc. – becomes exponentially more challenging when carer anxiety, depression, PTSD,

or dysregulation is present. Compounded by the developmental limitation of lan-

guage, such circumstances yield the potential for intergenerational transmission of

relational trauma (Browne & Winkelman, 2007).

Acting as an internal trigger, misattunement by the carer may precipitate feelings

of guilt and/or shame only to aggravate their dysregulation already experienced. This

further places the child at risk either directly through abuse/neglect or indirectly

through carer removal, incarceration, substance use, or risk of suicide. Such early

experiences for the child are likely, without intervention, to leave lasting effects on

physical and mental health through the lifespan (Cassidy & Mohr, 2001; Fisher &

Gunnar, 2010). Children may exhibit behavioural difficulties, suffer learning chal-

lenges, experience nightmares, bedwetting, become inconsolable when distressed, and

engage in early truancy (Waters, 2016).

In adolescence, these children may exhibit self-harming behaviours, become easily

stressed, and receive early mental health diagnoses (Waters, 2016). Continuing into

adulthood, they are susceptible to a plethora of physical and mental and psychiatric

issues (Fisher & Gunnar, 2010). Neurologically, prolonged exposure to relational

trauma negatively affects brain development (Teicher et al., 2010). Decreased hip-

pocampal volume and shrunken prefrontal cortex impact speech development,

574 ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy

Somatic Resources in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

memory formation, and the capacity for logic and reasoning (Schore, 2010; Seigel,

2015; Stien & Kendall, 2004).

Infancy and early childhood is a period of significant growth and development of

neurological, physiological, social, and behavioural systems. During this crucial time,

experiences that include neglect, abuse, and/or lack of carer attunement or sufficient

soothing are common in cases of relational trauma. Relational trauma is distinguished

from the usual missteps of parents when it results in chronic and persistent autonomic

nervous system (ANS) and emotional dysregulation in the child (Cassidy & Mohr,

2001). Parents and carers who are inconsistent, unavailable, or unskilled in providing

physical and emotional safety and nourishment become sources of distress for these

infants and young children. Such carers also struggle with their own histories of abuse

and neglect, often without sufficient or useful support and care themselves, which

potentially perpetuates generationally transmitted cycles of physiological and emo-

tional dysregulation (Enlow et al., 2014).

Relational trauma is complex and has many aspects to consider; however, the first

task in psychotherapy is to help the family members and the family unit regulate

hyper- and hypo-arousal (Ford & Courtois, 2009). This article will now focus atten-

tion on efforts to stabilise ANS dysregulation in carers, infants, and the pair together,

using the concepts and techniques of sensorimotor psychotherapy.

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

Sensorimotor psychotherapy (SP), as developed by Pat Ogden and colleagues, is a

method that is well suited to addressing the ANS and emotional dysregulation of rela-

tional trauma often succeeding where words are unavailable or insufficient as descrip-

tors of experience. SP is also a body-inclusive approach advancing the notion that

beneath conscious verbal narratives lies a rich somatic narrative ripe with information

to guide solutions for resolving both the present moment experiences of dysregulation

and the historical origins of current challenges. Since SP does not reply solely on lan-

guage for its effectiveness, it offers a means with which to explore the non-verbal

realm of trauma.

The therapist notes, tracks, conceptualises, and draws the client’s attention to

specific aspects of the somatic narrative, which informs the therapeutic process and

shapes decisions about important choice points. Of interest to our purpose in this

article is the observation and attention given to states of dysregulation. The SP per-

spective would prioritise understanding the client’s expression of dysregulation in its

somatic form, developing the client’s awareness of how dysregulation manifests for

them (if the client is capable of this awareness, and if not, would take the time to

develop skills for somatic awareness), and then developing a few robust somatic

resources to use to support the modulation of arousal and the regulation of the

accompanying emotion. This requires the therapeutic containment of the arousal and

the ability to refrain from premature attempts to reprocess traumatic memories that

feed dysregulated states until a minimal degree of stabilisation is achieved.

Working with the body through physical sensation, muscle tonicity, information

from the five senses, gestures, and movement is especially relevant when working with

children because it is the language of their experience since their cognitive sophistica-

tion is not yet developed. This is not to say that feelings or thoughts or words are

absent from the approach, but the SP-trained therapist is encouraged to look beneath

ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy 575

Rochelle Sharpe Lohrasbe and Pat Ogden

or to the somatic level of experience and meaning in specific ways to promote regula-

tion. Employing principles of neuroplasticity, which we can capitalise upon by helping

clients experience something new in the present moment, current, corrective experience

is sought to overwrite the troubling experience of the past (Ogden, Minton, & Pain,

2006). As carers work individually and with the child as a family, sometimes in sepa-

rate sessions and sometimes in family sessions, creating new experiences in a safe envi-

ronment with a therapist who can slow down the rapid pace of dysregulation, the

behaviours related to old neural pathways can be understood and new neural pathways

can be created allowing for other more adaptive outcomes (Siegel, 2015).

This approach is compatible with the view that the human brain is sensitive to

experience. Early experience through attachment relationships elicits states of calm

and states of stress that can influence the child’s ways of being in and interacting with

people and the world. Chronic arousal fluctuation or persistent states of either hyper-

or hypo-arousal in a child’s nervous system are likely to shape the structure and func-

tion of the developing brain, and ultimately begin to establish a sense of self limited

by the cycles of dysregulated arousal (Siegel, 2015). Children who experience persis-

tent stress/distress are more likely to become anxious, avoidant, or disorganised across

situations or with certain people in their growing circles. By adolescence the tendency

towards one or the other or rapid cycling can be well established. We propose that

the regulation of a nervous system in flux is best accomplished through the body

using somatic resources.

A Somatic Approach to Autonomic Nervous System Regulation

Dysregulation occurs when people endure experiences that compromise typical neuro-

logical development. As stated, these impede cognitive capacities. Thus, the client’s

ability to integrate the gains of therapy is limited. Efforts directed at teaching symp-

tom management without stabilising clients’ neurological and physiological dysregula-

tion may be diluted or even ineffective given diminished cognitive abilities. This may

account for the all too frequent phenomena of clients needing repeated contact with

health care providers to assist with safety and stabilisation despite their clients having

attended programs which taught symptom management skills or provided psychoedu-

cation on what clients should and could do to manage their distress (Clark, Classen,

Fourt, & Shetty, 2015). Dysregulation compromises clients from making use of inter-

ventions and may promote dependence on therapists to manage dysregulation. Thus,

early attention to the states of dysregulation is critical and may serve to ‘teach the cli-

ent to fish’ and increase chances that clients can use what they are taught should

future distress arise (Ogden et al., 2006).

Dysregulation in carers may be exhibited in a plethora of symptoms and behav-

iours which can ebb and flow with their levels of stress and distress of living situations

and circumstances. Additionally, triggers can emerge from their own internal triggers,

such as feelings of inadequacy, images or flashbacks of past abuse, and so forth. This

means there can be unanticipated or unpredictable periods of great turmoil sprinkled

with periods of relative calm and stability. One end of the spectrum can include full-

on diagnoses of depression, anxiety, personality disorders, substance issues, and disso-

ciative disorders occurring in singularity or as multiple diagnoses, which build in

intensity and may be evidenced by increased contact with mental health professionals,

social services, or even hospitalisations (Clark et al., 2015). At the other end, carers

576 ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy

Somatic Resources in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

seem to be making gains and striving towards a tolerable existence. The common

antecedent factor is whatever historical or current traumatic experience has occurred

or is occurring. It should be emphasised that when carers are unstable, they cannot

solve the normal problems of life because they cannot think clearly. Therefore, again,

regulation of physiological dysregulation is paramount, since physiological regulation

likely underlies emotional and cognitive capacities for coping.

When working with states of arousal it is helpful to have a conceptual framework

to concretise for both therapist and client. The window of tolerance (Siegel, 1999) as

part of the SP Modulation Model (Ogden et al., 2006) provides such a framework.

Modulation Model

The Modulation Model (Ogden et al., 2006) offers a multipurpose conceptual frame-

work: to assess present experience of regulation/dysregulation and accompanying vehe-

ment emotions (i.e., rage, terror, panic, despair: Janet, 1889) of survival, to determine

options for resourcing intervention, and to evaluate effects of intervention within ses-

sions and over time. It offers a measure of regulation/dysregulation. Assessing together

whether arousal is within a window can also be used to determine readiness to work

with traumatic recollections/memory for the caregiver.

Arousal refers to physiological functioning that is evident in such indicators as

heart rate, breath rate, muscle tension, and impulse for movement, all of which can

be signs of arousal that are outside the window of tolerance. High arousal is hyper-

arousal related to impulses to frantically reach for help, flee, fight, or freeze and very

low arousal is hypoarousal related to giving up or feeling sleepy). Survival-related

arousal is accompanied by vehement emotions such as rage, terror, panic, and extreme

despair, which are more difficult to resolve than the physiology itself (Janet, 1889).

The window of tolerance can help clients differentiate between, for example, fear or

being scared and terror, or anger and rage (see Figure 1).

Parsing out the emotional aspects to promote agency and influence over one’s fluc-

tuating states is empowering for clients. For clients who are overwhelmed by their

internal sensations, emotions, and thoughts, limiting the type and amount of informa-

tion can be supportive of regulation in and of itself but it also means that the client

has only to deal with a circumscribed amount of information at a time that is possible

for them to integrate. Thus, clients can begin to experience a sense of hope and

agency in managing their experience. For example, a common physiological response

when triggered into dysregulation is a racing heart. If the focus is drawn to the emo-

tion that accompanies the racing heart the client’s fear can escalate and they can

become focused on the potential for a panic attack.

In SP, we would separate out the emotional experience and any cognitive detail

(like the words ‘something really bad is going to happen’) and direct the client’s

attention exclusively to their heart rate. Then the therapist can use the concept of the

window of tolerance to discover where in their window their arousal lies with a racing

heart (typically in the hyperaroused zone). Together, the client and therapist can learn

somatic resources – direct physical interventions – that can help to slow the client’s

heart rate. This is accomplished perhaps by slowing breath, by connecting with the

feet, or by lifting the rib cage – all while checking in on the client’s experience until

together therapist and client find the somatic resource that slows the heart rate and

returns the arousal to within the window of tolerance.

ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy 577

Rochelle Sharpe Lohrasbe and Pat Ogden

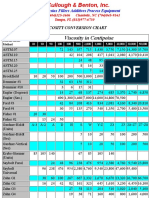

FIGURE 1

The Modulation Model. Ogden & Minton, 2000; Ogden et al., 2006. Differentiates the states of arou-

sal and dysregulation. Guides therapeutic intervention to expand the window of tolerance while redu-

cing the number, duration, and intensity of symptoms and experience outside the window of tolerance.

*Phrase coined by D. Siegel, 1999.

Sometimes a little experimentation is necessary to ensure the right fit of resource to

symptom and individual nervous system. As time and care are taken to maximise the

felt sense of safety and control, perhaps clients notice that clarity returns to their

thinking. Soon, and often with effort and intention and practice, clients learn specific

somatic resources to influence their own experience and develop a sense of agency in

the modulation of their arousal which can be returned to at will during times of stress.

In the case of the family, carers can learn and teach the same ideas to their chil-

dren. Or, perhaps they simply need to use their newfound skill to regulate their own

arousal and their children will follow. When carers can regulate their own arousal

within a window of tolerance this will also influence their child’s ability to regulate

arousal tolerance. Carers could possibly try a ‘let’s do this together’ approach whereby

the family can practice slowing breath together and checking heart rates together.

Other examples include relaxing the jaw or other areas of tension when hyper-

arousal- related anger/rage/panic surface, or standing up, doing jumping jacks, or

bouncing on a therapy ball, should hypoarousal related despair/hopelessness/shame

begin to reveal itself.

Co-regulation via mirror neurons (Pfeifer, Iacoboni, Mazziotta, & Dapretto,

2008) and vagal tone (Porges, 2011) of the ventral vagal branch of the parasympa-

thetic nervous system, which are tagged to facial muscles and expressions, tone of

voice, and eye contact, are both conceptualised as the domain within the window of

tolerance. Mirror neurons may factor in since it is possible that the carer’s body mani-

festation of emotional experiences of panic, despair, terror, or rage, such as clenched

fists, collapsed posture, or tense shoulders are being mirrored by the child. Addition-

ally, physiological manifestations of a carer’s dysregulation such as rapid heart rate or

trembling may be experienced vicariously by a child. Thus, the child’s heart rate,

578 ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy

Somatic Resources in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

respirations, and muscularity may mimic that of their carer’s. A soft tone of voice,

gentle eye contact at the child’s level, accompanied by a soothing touch may go fur-

ther to stabilise arousal from any particular words that might be spoken, striving for

ventral vagal expressions to down regulate hyperarousal and upregulate dorsal vagal

hypoarousal.

Somatic Resourcing

One of the primary methods of helping clients learn how to manage symptoms

including dysregulation involves teaching them how to stabilise their arousal. Since

dysregulation compromises cognitive functioning, efforts directed towards reasoning

and logic to stabilise arousal can be misguided. Instead, a category of somatic

resources, or the embodiment of non-somatic resources, can directly mitigate auto-

nomic nervous system arousal.

Somatic resources

When arousal reaches the upper edges of the window of tolerance physiological changes

influence emotion and thought. Increased heart rate and breathing affect one’s perceived

safety as action systems for survival are triggered. Many approaches attempt to address

accompanying emotions such as fear. Often this approach enhances or increases the

intensity of the fear rather than achieving the desired reduction. By tracking and attend-

ing to the physical constituents of the fear, dysregulation can be stabilised and cognitive

capacities can return to within the window of tolerance as regulation of arousal occurs.

Some examples of somatic resources include spinal alignment, orienting, and the

more commonly known breath and grounding. Key to the SP approach is to establish

a felt sense of the resource and its relationship to the window of tolerance and ideally

how the resource can restore physiological states of calm and stability. Merely talking

about or explaining the resource does not ensure the client fully appreciates or is able

to use the resource effectively when dysregulation begins. The therapist engages in the

resource themselves, by demonstrating deeper breath, aligning their own spine, using

self-touch along with the client, and so forth. This is helpful in setting clients at ease

and practicing the resource together with the therapist.

A powerful somatic resource is touch. Important to its power is the quality of the

touch. Parents frequently soothe distressed or upset children by gently placing their

hand on the child’s shoulder or taking the child into their arms for a hug. Physical

contact – self touch, or touch from another person – at the right time, on the right

place, and with the right pressure and compassion can quickly return both child and

caregiver to their windows of tolerance.

Eye gaze as a somatic and relational resource in the parent–child dyad also holds

promise when used in specific ways (Mikulincer, Shaver, & Horesh, 2006; Porges,

2011). Encouraging challenged caregivers to look into their child’s eyes during

moments of calm can support bonding and arousal regulation.

The therapist’s role in resourcing and stabilising dysregulation goes beyond psy-

choeducation and discussion. The therapist seeks to create experiences to demonstrate

how somatic resources can help regulate arousal, and facilitate qualitative interactions

between carer and child. All the while, the therapist pays close attention to indicators

such as hesitation discomfort or awkwardness in the carer that signals the need to

explore further. As the therapist draws attention to the carer’s reactions, the

ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy 579

Rochelle Sharpe Lohrasbe and Pat Ogden

opportunity to revisit, reprocess, and resolve past experiences of the carer can be cru-

cial to stopping cycles of dysregulation.

Embodying non-somatic resources

Just as it is desirable for the client to experience a felt sense of a somatic resource, it

is also valuable to achieve a felt sense of a non-somatic resource. For example, if a cli-

ent finds music to be calming then the session can be used to further explore the

calming physical and physiological effects that music provides. Having the client expe-

rience the music through their senses and sensations while observing the effects of lis-

tening to the music on their heart rate breath, muscle tone, and so forth is the

embodiment of a non-somatic resource. Other examples might include the physical

resource of walking in nature, the comfort of a good friend listening, the receiving of

social services, attending a parent–tot play group, etc.

The embodiment of non-somatic resources offers great flexibility and endless

opportunities to tailor the resource to the client. Any resource can be embodied by

placing an emphasis on the felt sense of the resource through its physiological, sen-

sory, or movement components; then exploring the affectual and cognitive qualities

of the felt sense.

By expanding the regulatory capacities of children and their carers using somatic

resources, systems of survival, attachment, and daily life are influenced and provide

the foundation for further therapeutic opportunities in individual and family interven-

tion.

References

Browne, C., & Winkelman, C. (2007). The effect of childhood trauma on later psychological

adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(6), 684–697. Retrieved from https://doi.

org/10.1177/0886260507300207

Cassidy, J., & Mohr, J.J. (2001). Unsolvable fear, trauma, and psychopathology: Theory,

research, and clinical considerations related to disorganized attachment across the lifespan.

Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8, 275–298.

Clark, C., Classen, C.C., Fourt, A., & Shetty, M. (2015). Treating the Trauma Survivor: An

Essential Guide to Trauma-informed Care. New York: Routledge.

Enlow, M.B., Egeland, B., Carlson, E., Blood, E., & Wright, R.J. (2014). Mother–infant

attachment and the intergenerational transmission of posttraumatic stress disorder. Develop-

ment and Psychopathology, 26(1), 41–65. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/

S0954579413000515

Fisher, P.A., & Gunnar, M. (2010). Early life stress as a risk factor for disease in adulthood,

in R.A. Lanius, E. Vermetten & C. Pain (Eds.), The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health

and Disease: The Hidden Epidemic (pp. 133–141). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Ford, J.D., & Courtois, C.A. (2009). Best practices in psychotherapy for children and adoles-

cents, in C.A. Courtois & J.D. Ford (Eds.), Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders:

An Evidence-Based Guide (pp. 59–81). New York: The Guilford Press.

Janet, P. (1889). L’automatisme Psychologique. Paris: Alcan.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P.R., & Horesh, N. (2006). Attachment bases of emotion regulation

and posttraumatic adjustment, in D.K. Snyder, J.A. Simpson, & J.N. Hughes (Eds.), Emo-

tion Regulation in Families: Pathways to Dysfunction and Health (pp. 77–99). Washington,

DC: American Psychological Association.

580 ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy

Somatic Resources in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

Ogden, P., & Minton, K. (2000). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: One method for processing

traumatic memory. Traumatology, 6(3), 149–173.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to

Psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Pfeifer, J.H., Iacoboni, M., Mazziotta, J.C., & Dapretto, M. (2008). Mirroring others’

emotions relates to empathy and interpersonal competence in children. NeuroImage, 39(4),

2076–2085. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.032

Porges, S.W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attach-

ment, Communication, and Self-regulation. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Schore, A. (2010). Relational trauma and the developing right brain: The neurobiology of

broken attachment bonds, in T. Baradon (Ed.), Relational Trauma in Infancy (pp. 19–47).

London: Routledge.

Siegel, D. (2015). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape

Who We Are (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Stien, P.T., & Kendall, J. (2004). Psychological Trauma and the Developing Brain: Neurologi-

cally Based Interventions for Troubled Children. New York: The Haworth Press Inc.

Teicher, M.H., Rabi, K., Sheu, Y., Seraphin, S.B., Andersen, S.L., Andersen, C.M., Choi, J.,

& Tomoda, A. (2010). Neurobiology of childhood trauma and adversity, in R.A. Lanius,

E. Vermetten, & C. Pain (Eds.), The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease:

The Hidden Epidemic (pp. 112–122). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Waters, F.S. (2016). Healing the Fractured Child: Diagnosis and Treatment of Youth with Disso-

ciation. New York: Springer Publishing Co., Inc.

ª 2017 Australian Association of Family Therapy 581

Copyright of Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy is the property of Wiley-

Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv

without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print,

download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Trauma On Brain DevelopmentDocument29 pagesTrauma On Brain DevelopmentChirra Williams100% (1)

- Grand v. Schwarz - Brainspotting Trademark PDFDocument12 pagesGrand v. Schwarz - Brainspotting Trademark PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Trauma Therapist ToolkitDocument23 pagesTrauma Therapist ToolkitRoxana100% (1)

- Working With Traumatic Memories To Heal Adults With Unresolved Childhood Trauma - Neuroscience, Attachment Theory and Pesso Boyden System Psychomotor Psychotherapy PDFDocument305 pagesWorking With Traumatic Memories To Heal Adults With Unresolved Childhood Trauma - Neuroscience, Attachment Theory and Pesso Boyden System Psychomotor Psychotherapy PDFAlessandro Papa100% (3)

- ACEs Connected LifeDocument26 pagesACEs Connected LifeYari MarreroNo ratings yet

- Alicia F. Lieberman, Patricia Van Horn - Psychotherapy With Infants and Young Children - Repairing The Effects of Stress and Trauma On Early Attachment (2008)Document385 pagesAlicia F. Lieberman, Patricia Van Horn - Psychotherapy With Infants and Young Children - Repairing The Effects of Stress and Trauma On Early Attachment (2008)rosana80% (5)

- Dissociation Following Traumatic Stress: Etiology and TreatmentDocument19 pagesDissociation Following Traumatic Stress: Etiology and TreatmentNievesNo ratings yet

- Dissociative Amnesia: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Course, and DiagnosisDocument26 pagesDissociative Amnesia: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Course, and DiagnosisZiggy GonNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in The Wake of Loss - Strategies For Working With The Missing Stage of GriefDocument48 pagesAnxiety in The Wake of Loss - Strategies For Working With The Missing Stage of GriefAlguémNo ratings yet

- Psychological First AidDocument16 pagesPsychological First AidYerson Alarcon MoralesNo ratings yet

- Complex Childhood TraumaDocument11 pagesComplex Childhood TraumaAkinosan100% (1)

- Revised Emotion Regulation Homework Sheet 1Document1 pageRevised Emotion Regulation Homework Sheet 1rileyjenNo ratings yet

- Manual Diversity Therapy RoomDocument21 pagesManual Diversity Therapy RoomAlguémNo ratings yet

- Complex PTSDDocument21 pagesComplex PTSDRyne ZuziNo ratings yet

- Janina 1Document6 pagesJanina 1AngelesLunaJuradoNo ratings yet

- Creating A Trauma Informed Child Welfare SystemDocument10 pagesCreating A Trauma Informed Child Welfare SystemiacbermudaNo ratings yet

- The Science of NeglectDocument20 pagesThe Science of NeglectdrdrtsaiNo ratings yet

- Interoception and CompassionDocument4 pagesInteroception and CompassionMiguel A. RojasNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Resilience To Personality, Coping, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Young AdultsDocument15 pagesRelationship of Resilience To Personality, Coping, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Young AdultsBogdan Hadarag100% (1)

- Theory: PolyvagalDocument2 pagesTheory: PolyvagalWayne CasanovaNo ratings yet

- Brief Family-Based Crisis Intervention (Cftsi) - Stephen BerkowitzDocument20 pagesBrief Family-Based Crisis Intervention (Cftsi) - Stephen Berkowitzapi-279694446No ratings yet

- The Polyvagal Parenting Playbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Interactive Strategies for Every Age and StageFrom EverandThe Polyvagal Parenting Playbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Interactive Strategies for Every Age and StageNo ratings yet

- FZ6 Vs Z750Document6 pagesFZ6 Vs Z750Andrea Manca100% (1)

- TlctraumaDocument7 pagesTlctraumaapi-356243627No ratings yet

- Domestic Violence - Shrey & MusabDocument6 pagesDomestic Violence - Shrey & MusabMusab AlbarbariNo ratings yet

- Bowlby - The Nature of The Child's Tie To His MotherDocument26 pagesBowlby - The Nature of The Child's Tie To His Motherinna_rozentsvit100% (1)

- 50 Risks To Take With Your KidsDocument211 pages50 Risks To Take With Your KidsVăn Hải NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Grief During The Pandemic Internet-Resource-GuideDocument76 pagesGrief During The Pandemic Internet-Resource-GuideAnastasija TanevaNo ratings yet

- World Handbook of Existential TherapyDocument10 pagesWorld Handbook of Existential TherapyFaten SalahNo ratings yet

- Star Conference Feeling Buddies - Our JourneyDocument27 pagesStar Conference Feeling Buddies - Our JourneyfernandapazNo ratings yet

- Srimadbhagwata Mahapuran With MahabharataDocument505 pagesSrimadbhagwata Mahapuran With Mahabharataprapnnachari100% (6)

- Article Taming The Terrible MomentsDocument3 pagesArticle Taming The Terrible Momentsapi-232349586No ratings yet

- Profile of A Therapeutic CompanionDocument3 pagesProfile of A Therapeutic CompanionPatricia BaldonedoNo ratings yet

- Emdr Protocol Standard En-GbDocument4 pagesEmdr Protocol Standard En-GbNadia100% (1)

- NICABM InfoG StructuralDissociationModelDocument2 pagesNICABM InfoG StructuralDissociationModelssjeliasNo ratings yet

- What Happened To You Book Discussion Guide-National VersionDocument7 pagesWhat Happened To You Book Discussion Guide-National Versionaulia normaNo ratings yet

- NICABM InfoG Window of Tolerance RevisedDocument1 pageNICABM InfoG Window of Tolerance Revisedsemsem0% (1)

- Congresso Roma BROCHURE ENG DefDocument13 pagesCongresso Roma BROCHURE ENG DefISCFormazione100% (1)

- Teens in Distress SeriesDocument4 pagesTeens in Distress SeriesdarinaralucaNo ratings yet

- Lanius & Frewen 2006 - Toward A PsychobiologyDocument15 pagesLanius & Frewen 2006 - Toward A PsychobiologyCarlos Eduardo NorteNo ratings yet

- Appearance Is Not Always: - We Don't Need A Secure BaseDocument4 pagesAppearance Is Not Always: - We Don't Need A Secure BaseMike ChristopherNo ratings yet

- Taylor 2006 Tend and BefriendDocument6 pagesTaylor 2006 Tend and BefriendGer RubiaNo ratings yet

- CFT HandoutsDocument49 pagesCFT HandoutsEsmeralda Herrera100% (2)

- Hydrogenium Homeopathic RemedyDocument6 pagesHydrogenium Homeopathic RemedySatya PalNo ratings yet

- The 10 Steps & Ogden'S Sensorimotor PsychotherapyDocument29 pagesThe 10 Steps & Ogden'S Sensorimotor Psychotherapydocwavy9481No ratings yet

- Trauma Solutions Relational Empowerment Training Slides PDFDocument23 pagesTrauma Solutions Relational Empowerment Training Slides PDFihcammaNo ratings yet

- Attachment TheoryDocument4 pagesAttachment TheoryMohammedseid AhmedinNo ratings yet

- Grief and Narrative TherapyDocument13 pagesGrief and Narrative TherapySidney OxboroughNo ratings yet

- Play Theraphy (Unfinished)Document21 pagesPlay Theraphy (Unfinished)OmyNo ratings yet

- Ensink 2014 Mentalización TraumaDocument15 pagesEnsink 2014 Mentalización TraumaDanielaMontesNo ratings yet

- Adverse Childhood ExperiencesDocument9 pagesAdverse Childhood Experiencesapi-487854212No ratings yet

- Liotti Trauma Attachment 2004Document39 pagesLiotti Trauma Attachment 2004samathacalmmindNo ratings yet

- Part 1 Artificial Window of Tolerance WorkbookDocument28 pagesPart 1 Artificial Window of Tolerance WorkbookFaten SalahNo ratings yet

- Death Anxiety and Its Association With Hypochondriasis PDFDocument8 pagesDeath Anxiety and Its Association With Hypochondriasis PDFRebeca SilvaNo ratings yet

- Early Interaction and Developmental Psychopathology: Volume I: Infancy Gisèle Apter Emmanuel Devouche Maya GratierDocument229 pagesEarly Interaction and Developmental Psychopathology: Volume I: Infancy Gisèle Apter Emmanuel Devouche Maya GratierRoberto Alexis Molina Campuzano100% (1)

- Motor ArduinoDocument41 pagesMotor ArduinoyankurokuNo ratings yet

- Guilt and ChildrenFrom EverandGuilt and ChildrenJane BybeeNo ratings yet

- DOD-MST-INS-002, MST For Installation of Field Instruments.-Rev-1Document15 pagesDOD-MST-INS-002, MST For Installation of Field Instruments.-Rev-1BharathiNo ratings yet

- Viscosity Conversion ChartDocument2 pagesViscosity Conversion ChartCorvetteNo ratings yet

- Schore2001 PDFDocument69 pagesSchore2001 PDFMihaela ButucaruNo ratings yet

- Dennis McGuire: Mental Wellness and Good Health in Teens and Adults With Down SyndromeDocument23 pagesDennis McGuire: Mental Wellness and Good Health in Teens and Adults With Down SyndromeGlobalDownSyndromeNo ratings yet

- Briere ITCT-A Final PDFDocument119 pagesBriere ITCT-A Final PDFDave HenehanNo ratings yet

- Stress and Personality DDocument7 pagesStress and Personality DAdriana NegrescuNo ratings yet

- Trauma Guideline Manual PDFDocument157 pagesTrauma Guideline Manual PDFsilviaemohNo ratings yet

- 12 Quarter 1 Module 12 - Timeline-Of-ExtinctionDocument13 pages12 Quarter 1 Module 12 - Timeline-Of-ExtinctionMah Jane Divina100% (1)

- Strategic Significance of Arabian SeaDocument4 pagesStrategic Significance of Arabian SeaShamshad Ali RahoojoNo ratings yet

- Advances in Fatigue Analysis TechnologiesDocument38 pagesAdvances in Fatigue Analysis TechnologiesMarcelino Pereira Do NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Deep Audio ClassificationDocument10 pagesDeep Audio ClassificationVinayNo ratings yet

- PP No. 61 Tahun 2009 (Kepelabuhan) English VersionDocument54 pagesPP No. 61 Tahun 2009 (Kepelabuhan) English VersionSetyaning KartikaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Eigenvalues 1Document9 pagesNotes On Eigenvalues 1Vivian BiryomumaishoNo ratings yet

- National Building Code of The Philippines SummaryDocument2 pagesNational Building Code of The Philippines SummaryScott AlilayNo ratings yet

- Designated Airspace HandbookDocument153 pagesDesignated Airspace HandbookBradley NorthcotteNo ratings yet

- IMGS - QTF - A20 - For Cargo VesselDocument4 pagesIMGS - QTF - A20 - For Cargo VesselLion DayNo ratings yet

- IUPAC - Practice SheetDocument5 pagesIUPAC - Practice SheetRishi NairNo ratings yet

- Normal Distribution and Standard Normal DistributionDocument46 pagesNormal Distribution and Standard Normal DistributionazmanrafaieNo ratings yet

- On The Optimal Weighting Matrix For The GMM System Estimator in Dynamic Panel Data ModelsDocument28 pagesOn The Optimal Weighting Matrix For The GMM System Estimator in Dynamic Panel Data ModelsNeemaNo ratings yet

- 21wcss Programacao Final PDFDocument279 pages21wcss Programacao Final PDFlocometrallaNo ratings yet

- Grendel ZodiacDocument3 pagesGrendel ZodiacSteven LaiNo ratings yet

- Bowex KaplinDocument30 pagesBowex Kaplinmustafa çetinkayaNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 Maths Practice Sheet Decimals (Ekam and Ena) (01!09!2017)Document5 pagesGrade 6 Maths Practice Sheet Decimals (Ekam and Ena) (01!09!2017)praschNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 11 Physics Notes For Properties of Bulk MatterDocument20 pagesCBSE Class 11 Physics Notes For Properties of Bulk MatterAyush Kumar100% (1)

- Neligan Vol 4 Chapter 10 MainDocument20 pagesNeligan Vol 4 Chapter 10 MainisabelNo ratings yet

- FO-SHE-02 Risk Assessment FormDocument2 pagesFO-SHE-02 Risk Assessment FormNeil OsenaNo ratings yet

- Law Essay SampleDocument8 pagesLaw Essay Sampleheffydnbf100% (2)

- Respuestas AtlanticaDocument5 pagesRespuestas AtlanticaWilson Zambrano0% (1)

- Jurnal Antropologi: Isu-Isu Sosial Budaya: Modal Sosial Kelompok Rentan Sebagai UpayaDocument10 pagesJurnal Antropologi: Isu-Isu Sosial Budaya: Modal Sosial Kelompok Rentan Sebagai UpayaSari IntanNo ratings yet

- Nikon Metrology SolutionsDocument44 pagesNikon Metrology SolutionsBinh NguyenNo ratings yet