Professional Documents

Culture Documents

White Mutiny: 184 A Brief History of Modern India

Uploaded by

Sonia Sabu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views2 pagesOriginal Title

The Army

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views2 pagesWhite Mutiny: 184 A Brief History of Modern India

Uploaded by

Sonia SabuCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

The Army, which was at the forefront of the outbreak,

was thoroughly reorganised and British military policy came

to be dominated by the idea of “division and counterpoise”.

The British could no longer depend on Indian loyalty, so the

number of Indian soldiers was drastically reduced even as

the number of European soldiers was increased. The concept

of divide and rule was adopted with separate units being

created on the basis of caste/community/region. Recruits

were to be drawn from the ‘martial’ races of Punjab, Nepal,

and north-western frontier who had proved loyal to the British

during the Revolt. Effort was made to keep the army away

from civilian population.

The Army Amalgamation Scheme, 1861 moved the

Company’s European troops to the services of the Crown.

Further, the European troops in India were constantly revamped

by periodical visits to England, sometimes termed as the

‘linked-battalion’ scheme. All Indian artillery units, except a

few mountain batteries, were made defunct. All higher posts

in the army and the artillery departments were reserved for

the Europeans. Till the first decade of the twentieth century,

no Indian was thought fit to deserve the king’s commission

and a new English recruit was considered superior to an

Indian officer holding the viceroy’s commission.

The earlier reformist zeal of a self-confident Victorian

184 ✫ A Brief History of Modern India

White Mutiny

In the wake of the transfer of power from the British East India

Company to the British Crown, a section of European forces

employed under the Company resented the move that required the

three Presidency Armies to transfer their allegiance from the defunct

Company to the Queen, as in the British Army. This resentment

resulted in some unrest termed as White Mutiny.

Prior to 1861, there were two separate military forces in India,

operating under the British rule. One was the Queen’s army and

the other comprised the units of the East India Company. The

Company’s troops received batta, extra allowances of pay to cover

various expenditures related to operations in areas other than the

home territories. With transfer of power, the batta was stopped.

Lord Canning’s legalistic interpretation of the laws surrounding the

transfer also infuriated the affected White soldiers.

The White Mutiny was seen as a potential threat to the already

precarious British position in India with a potential of inciting renewed

rebellion among the ‘still excited population in India’. The demands

of the ‘European Forces’ included an enlistment bonus or a choice

of release from their obligations. Finally, the demand for free and

clear release with free passage home was accepted, and men opted

to return home. It is also believed that open rebellion and physical

violence on the part of ‘European Forces’ were such that there

was little possibility of being accepted into the ‘Queen’s Army’.

liberalism evaporated as many liberals in Britain began to

believe that Indians were beyond reform. This new approach—

‘conservative brand of liberalism’, as it was called by Thomas

Metcalf—had the solid support of the conservative and

aristocratic classes of England who espoused the complete

non-interference in the traditional structure of Indian society.

Thus the era of reforms came to an end.

The conservative reaction in England made the British

Empire in India more autocratic; it began to deny the

aspirations of the educated Indians for sharing power. In the

long term, this new British attitude proved counter-productive

for the Empire, as this caused frustrations in the educated

Indian middle classes and gave rise to modern nationalism

very soon.

The policy of divide and rule started in earnest after

the Revolt of 1857. The British used one class/community

The Revolt of 1857 ✫ 185

against another unscrupulously. Thus, socially, there was

irremediable deterioration. While British territorial conquest

was at an end, a period of systematic economic loot by the

British began. The Indian economy was fully exploited

without fear.

In accordance with Queen’s Proclamation of 1858, the

Indian Civil Service Act of 1861 was passed, which was to

give an impression that under the Queen all were equal,

irrespective of race or creed. (In reality, the detailed rules

framed for the conduct of the civil service examination had

the effect of keeping the higher services a close preserve

of the colonisers.)

Racial hatred and suspicion between the Indians and the

English was probably the worst legacy of the revolt. The

newspapers and journals in Britain picturised the Indians as

subhuman creatures, who could be kept in check only by

superior force. The proponents of imperialism in India

dubbed the entire Indian population as unworthy of trust and

subjected them to insults and contempt. The complete

structure of the Indian government was remodelled and based

on the notion of a master race—justifying the philosophy

of the ‘Whiteman’s burden’. This widened the gulf between

the rulers and the ruled, besides causing eruptions of political

controversies, demonstrations and acts of violence in the

coming period.

Significance of the Revolt

For the British the Revolt of 1857 proved useful in that it

showed up the glaring shortcomings in the Company’s

administration and its army, which they rectified promptly.

These defects would never have been revealed to the world

if the Revolt had not happened.

For the Indians, the 1857 Revolt had a major influence

View

In conceptual terms, the British who had started their rule as

‘outsiders’, became ‘insiders’ by vesting in their monarch the

sovereignty of India.

Bernard Cohn (in context of the Queen’s Proclamation)

186 ✫ A Brief History of

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Bar Exam Answers Useful Introductory LinesDocument15 pagesBar Exam Answers Useful Introductory LinesMelissa Mae Cailon MareroNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Fallen Angel Chapter OneDocument19 pagesFallen Angel Chapter OneDez Donaire100% (1)

- Part Vi. Correctional AdministrationDocument21 pagesPart Vi. Correctional AdministrationNelorene SugueNo ratings yet

- Ui V BonifacioDocument2 pagesUi V BonifacioCharisse Christianne Yu CabanlitNo ratings yet

- Chi Ming Tsoi vs. CADocument3 pagesChi Ming Tsoi vs. CAneo paul100% (1)

- B - SC - Geology AidedDocument9 pagesB - SC - Geology AidedSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- University of KeralaDocument5 pagesUniversity of KeralaSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- BscProspects 2023Document10 pagesBscProspects 2023Sonia SabuNo ratings yet

- The Material Issues That WentDocument2 pagesThe Material Issues That WentSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- The Growth of Sociology in IndiaDocument1 pageThe Growth of Sociology in IndiaSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Why The Revolt Failed: All-India Participation Was AbsentDocument2 pagesWhy The Revolt Failed: All-India Participation Was AbsentSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Chart 6.1: Distribution of Poultry and Livestock in India, 2012Document2 pagesChart 6.1: Distribution of Poultry and Livestock in India, 2012Sonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Emergence of Shadow ZoneDocument3 pagesEmergence of Shadow ZoneSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Civilians Join: 174 A Brief History of Modern IndiaDocument2 pagesCivilians Join: 174 A Brief History of Modern IndiaSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting IndiaDocument3 pagesFactors Affecting IndiaSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Continued Economic Growth and CallsDocument2 pagesContinued Economic Growth and CallsSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- The Onset of The Monsoon and WithdrawalDocument4 pagesThe Onset of The Monsoon and WithdrawalSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- The Transition SeasonDocument2 pagesThe Transition SeasonSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Two Roads To ModernisationDocument2 pagesTwo Roads To ModernisationSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Slavery Was An Institution Deeply Rooted in The Ancient WorldDocument4 pagesSlavery Was An Institution Deeply Rooted in The Ancient WorldSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Was There A European Renaissance' in The Fourteenth Century?Document2 pagesWas There A European Renaissance' in The Fourteenth Century?Sonia SabuNo ratings yet

- New Agricultural Technology: T T O 2018-19 144 T W HDocument2 pagesNew Agricultural Technology: T T O 2018-19 144 T W HSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Rapid Industrialisation Under Strong LeadershipDocument2 pagesRapid Industrialisation Under Strong LeadershipSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Stories From India's Poorest Districts, Penguin Books, New DelhiDocument1 pageStories From India's Poorest Districts, Penguin Books, New DelhiSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- The Story of TaiwanDocument2 pagesThe Story of TaiwanSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- T H GreenDocument13 pagesT H GreenSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- The Earliest Known Temple of The South, c.5000 (Plan) - Cuneiform LettersDocument3 pagesThe Earliest Known Temple of The South, c.5000 (Plan) - Cuneiform LettersSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights USDocument5 pagesBill of Rights USSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Liberalisation, Privatisation AND Globalisation: An AppraisalDocument9 pagesLiberalisation, Privatisation AND Globalisation: An AppraisalSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Indian Economy On The Eve of IndependenceDocument4 pagesIndian Economy On The Eve of IndependenceSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- LV3.085.The Wind in The Willows 85 - Jealous ToadDocument10 pagesLV3.085.The Wind in The Willows 85 - Jealous ToadThái TrươngNo ratings yet

- Print Only Chapter 4-The Hacienda de Calamba Agrarian ProblemDocument62 pagesPrint Only Chapter 4-The Hacienda de Calamba Agrarian ProblemJohn Mark SanchezNo ratings yet

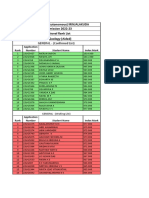

- Summary Expenses For RS and EQ ActivityDocument1 pageSummary Expenses For RS and EQ Activitypugalreigns05No ratings yet

- Legend Hotel vs. Realuyo AKA Joey Roa, G.R. No. 153511, 18 July 2012Document2 pagesLegend Hotel vs. Realuyo AKA Joey Roa, G.R. No. 153511, 18 July 2012MJ AroNo ratings yet

- Legal EnglishDocument4 pagesLegal EnglishTeona GabrielaNo ratings yet

- Fable Module II Group #10...Document3 pagesFable Module II Group #10...jazmin vidaljimenezNo ratings yet

- Rogers v. Tennessee Keeler v. Superior CourtDocument2 pagesRogers v. Tennessee Keeler v. Superior CourtcrlstinaaaNo ratings yet

- National Policy For The Empowerment of WomenDocument10 pagesNational Policy For The Empowerment of Womenavijitm_abcNo ratings yet

- At The Bookshop: Listening 7Document1 pageAt The Bookshop: Listening 7Wayra EvelynNo ratings yet

- Bug Bounty RelatedDocument36 pagesBug Bounty RelatedMichael ben100% (1)

- LetterDocument2 pagesLettercristine jagodillaNo ratings yet

- Jewish Standard, December 18, 2015, With SupplementsDocument112 pagesJewish Standard, December 18, 2015, With SupplementsNew Jersey Jewish StandardNo ratings yet

- Regular and Irregular VerbDocument5 pagesRegular and Irregular VerbNajmia HermawatiNo ratings yet

- Cabanatuan and Bonifacio HistoryDocument3 pagesCabanatuan and Bonifacio HistoryAnonymous LRs7fslNo ratings yet

- RIZALDocument6 pagesRIZALZeny Ann MolinaNo ratings yet

- ETHICS IN MNGT. ISSUES IN GOV DISCUSSION - GDNiloDocument7 pagesETHICS IN MNGT. ISSUES IN GOV DISCUSSION - GDNiloGlazed Daisy NiloNo ratings yet

- Halsbury's SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE (VOLUME 44 (1) (REISSUE) )Document218 pagesHalsbury's SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE (VOLUME 44 (1) (REISSUE) )MinisterNo ratings yet

- Chempakaraman Pillai and EmdonDocument19 pagesChempakaraman Pillai and Emdonkarthik arunmozhiNo ratings yet

- 2A Case Digest - PD 705Document4 pages2A Case Digest - PD 705Brozy MateoNo ratings yet

- Political Ideas: Case Study: Rwandan GenocideDocument7 pagesPolitical Ideas: Case Study: Rwandan GenocideWaidembe YusufuNo ratings yet

- Clu3m 01 GlossaryDocument6 pagesClu3m 01 GlossaryJude EinhornNo ratings yet

- Jesus Our Eucharistic Love: Eucharistic Life Exemplified by The SaintsDocument58 pagesJesus Our Eucharistic Love: Eucharistic Life Exemplified by The Saintssalveregina1917No ratings yet

- A Quilt For A CountryDocument7 pagesA Quilt For A CountryAlm7lekالملكNo ratings yet

- Artistes From Isles & Zonal Cultural Centre To Present Cultural Progs. at Marina Park & Amphitheatre, Anarkali From Dec. 23 To 25Document4 pagesArtistes From Isles & Zonal Cultural Centre To Present Cultural Progs. at Marina Park & Amphitheatre, Anarkali From Dec. 23 To 25Xerox HouseNo ratings yet

- Ankit KumarDocument14 pagesAnkit KumarArbaz KhanNo ratings yet