Professional Documents

Culture Documents

14 A, B, C and D of DRCA

14 A, B, C and D of DRCA

Uploaded by

Rahul Gupta0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views34 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views34 pages14 A, B, C and D of DRCA

14 A, B, C and D of DRCA

Uploaded by

Rahul GuptaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 34

A Contro)

Pa "Of ection of Tenany

so received, a8 the unexpirag

lease bears to the total periog

provided further that,

resaid, the landlord shal

sent per annum on the a

1 portio

DN of the con

‘ontract or a

of Agraarment

‘

OF contract or agreerr,

nent

any di

lefaul

II be lial 'S Made in making

mount Ee Pay Simple intoragt aren Yd as

ch he has omitted Tene rate of s

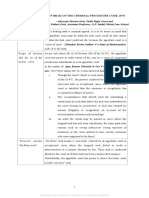

SYNOPSis

ease

OF failed to tatune

rr §. 14A—Introduction

: s, 14A—Object

4A and

' an Ss. 25A, 25B ang 25C are not violative of Art. 14 of the

§. 14A(1}—Conditions of applicability

§. 14A(1)—Landlord

en

noose

. §. 14A(1}—Being a i ‘

vate , mane 'n occupation of any residential accommodation

7 quired to vacate in pursuance

Government or authority of an order of the Central

8, $14A(1}—Purpose of letting i

residential 9 is irrelevant but accommodation must be

9. S.14A(1)}—Overrides the provisions of the Slum Act

10. Set mel at pe invoked even during the period of limited tenancy

11. $.14A(1}—Procedure for trial of an eviction petition under S. 14A

42. S. 14A(1)—Defences open in an eviction application under S. 140.

43. S. 14A(1}—Leave to defend a petition under the section

44, S.14A(1)—Applicability of S. 14(6) and S. 14(7)

45. S. 14A(1)}—Applicability of S. 19(1)

16. S.14A(1}—Claim of eviction must be bona fide

17. S. 14A(1}—Effect of modified circular dated 14-7-1977 on pending

proceedings

1. S. 144A4—Introduction.—This section was added for the first time by the

Delhi Rent Control (Amendment) Act, 1976, S. 5. It was preceded by

Ordinance No. 24 of 1975 which came into force on 1.12.75. And the Act which

superseded the Ordinance was made retrospective to take effect from the same

date, The section gives Government servants residing in Government

accommodation an immediate right to recover possession of their own houses.

S. 25B was also added primarily to implement this section and it provided

summary procedure but it was made applicable simultaneously to all

landlords/owners who required their houses on the ground of bona fide

requirement.

2. $. 144A—Object.—During the Emergency, the Government laid down as a

matter of policy that Government premises occupied by persons who had pret

own houses should be asked to vacate such accommodation occupied by them.

' th

Law of Rent Cor

ta

ww

cmd which penal »

van by a certain date bey

Mn The decision was taker

eos were required to

A were therefore added 4,,

r" ac ate

ment prem itor

4 Chapter TTI

houses within the time allowed ,

This section ane

1 to their own

of the Government calling upon the oe,

‘Pan

premises has been made cong,

chy

121978

euch oocupants to shif

fer

to vacate the

hor this reason the ore

he house for his own occupation

yment premises

is need for f!

Gover

Kasturi Lal’ the Supreme Court made the fotic,

ing

evidence of h

In Sarwan Singh ¥

observations: —

“The object of S. 144, as shown by its marginal note, is to conf,

right on certain landlords to recover “immediate Possession”

of

premises” belonging to them and which are in the possession of jy,

tenants. In the significant language of the marginal note, such a Tigh a

“to accrue” to a class of persons. The same concept is pursued dy

clarified in the body of Section 14A by providing that in ns

ee mentioned i ine section, a right will accrue to n

landlord “to recover immediat ossession of an’ is

by him.” mole any Premises let out

Again >—

“Whatever be the merits of that philosophy, the is

phy, the theory is

allottee from the Central Government or a local authority shout a

Pe a mercy of law’s delays while being faced with instant evi, a

2 Bs landlord save on payment of what in practice is penal mon

‘ac od with a Hobson's choice, to quit the official residence or mt

market rent fri the allotee had in tum to be afforded a ee

oped . Hous Stee: against his own tenant. With that end FS Vit oa

stand inthe way of th alo even the Slum Clearance Act, shall

allo om evicting hi x

the summary procedure i g his tenant by resortin,

te

Prescribed by Chapter III A. The ee

—_____

1. SeeR.K, Parikh

KAY. Uma Verma, 1978(1) RLR 423 (430).

2. AIR 197 5c

265 (272.3),

3. Wbid p.274 of at 3): 1978(2) RCR 445; 1977 rae

; 6: 1977 RCR

348,

7

- wal Control of Eviction of Tenant

1

to supp ort e

" Seon es r the view that the express

Pa ain Gi Cesidental suitability, and ee sim residential

; 2 » of lel was

eleva oy eel ourt quoted the above observation Pace

ao ¢ object was also further rvations in a later

wd eet the Delhi High Court explained in its social setting in this

Tse. F tr peld that pee also commented on the object” In this case

ie ao Pec} es ea S. Jaye were not available in

Io the ingredients of § a and that defence under S. 14A 1s

; . 144. The C

dt awellin ; ‘ ourt also interpreted the

jon ‘dwelling house’ used in the section. The scope of the section was

tai down in the form of propositions.

nd SS.

. S- ent tae 25B and 25C are not violative of Art. 14 of the

constitution: 4 question came up before the Courts in relation to the

jal proce ure laid down in S. 25B for trying only particular eviction

applications, ie., on the grounds contained in S. 14(1)(e) and S. 14A. The vires

ofS. 25 were challenged on the contention that it was violative of Art. 14 and

suffered from the vice of excessive delegation. The challenge was turned

down: In Ravi Dutt Sharma's case before the Supreme Court the attack was in

fact on the validity of Ss. 25A, 25B, 25C. It was not a case under S. 14A but an

eviction application under S. 14(1)(e) read with S. 25B, and the principal

yestion Was whether permission under the Slum Act was necessary before

filing the application. The landlord had applied for permission under the Slum

‘Act which was refused. He then filed the application without permission in

view of the Supreme Court decision in Sarwan Singh v. Kasturi Lal.4 It was in

this context that the validity of Ss. 25A, 25B and 25C was raised. The Supreme

Court laid down the law in the following words

“13, On a consideration, therefore, of the facts and circumstances of

the case and the law referred to above, we reach the following

conclusions:

(1) That Ss. 14A, 25A, 25B and 25C of the Rent Act are special

provisions so far as the landlord and tenant are concerned and in

view of the non-obstante clause these provisions would override

the existing law so far as the new procedure is concerned:

(2) That there is no difference either on principle or in law between

Ss. 14(1) (e) and 14A of the Rent Act even though two provisions

relate to eviction of tenants under different situations:

_—_—

1. Busching Schmitz (P) Lid. v. P.T. Menghani, AIR 1977 SC 1569: 1977(2) RCR 233: 1977 Raj LR

283.

2. VL. Kashyap v. R.P. Puri, 1977(1) RLR 397 (405): ILR 1977(1) Del 22.

3. Kewal Singh v. Lajwanti, AIR 1980 SC 161; Ravi Dutt Sharma v. Ratan Lal Bhargava,

SC 967: 1984(1) RR 357: 1984(1) RCJ 325.

AIR 1977 SC 265: 1977(2) SCR 421.

AIR 1984 SC 967 at 971.

AIR 1984

awe

Se Law of Rent Control in Petit ap

pter HHA of the Aimeng

(That the procedure incorporated in Chap Ling

Act into the Rent Act is in public interest and 16 P01 Violajiyg

Article 14 of the Constitution

(4) That in view of the procedure in ¢ hapter IA of the Rent Acy, the

Shim Act is rendered inapplicable to the extent of inconsisten,

and it is not, therefore, necessary for the landlord to oby,,7

permission of the Competent Authority under 5. 19 (1) (a) of the

Slum Act before instituting a suit for eviction and coming Within

S. 14 (1) (e) or 14A of the Rent Act.”

4, S. 14A(1)—Conditions of applicability. —They are:

(1) The landlord must be a person who is in actual occupation of

residential premises allotted to him by the Central Government or an

local authority; it is not necessary that he must be a Government

servant.

(2) He is required to vacate such premises by or in pursuance of a genera]

or special order made by the Central Government or authority and to

incur certain obligations in case of default.

(3) Such order is made on the ground that he owns a residential

accommodation, either in his own name or in the name of his wife or

dependent child, in the Union Territory of Delhi.

For a statement of the conditions for the applicability of the section, see B.N,

Muttoo v. Dr. T.K. Nandi! and Busching Schmitz v. P T Menghani2 Also see the

undermentioned case.3 We will consider these conditions separately.

5. S. 14A(1)—Landlord.—It implies that the occupant of the Government

premises must be the owner. Where wife is the owner, an application by the

“husband will not be maintainable.‘ But a petition by her under S. 25B on the

ground contained in S. 14(1)(e) may be made on the ground of her husband's

requirement.5 The occupant may be one of the co-owners. He may apply along

with the other co-owners or by impleading them as respondents.°

The occupant may not be the owner in the strict sense. For that see

commentary under S. 14(1)(e). The same person should be owner, landlord

and allottee of Government accommodation to maintain an application under

the section.”

AIR 1979 SC 460: 1979(15) DLT 36 SC: 1979(1) RCJ 316: 1979(1) and RCR 144: 1978(2) SCR

409 and Busching Schmitz v. P.T. Menghani, AIR 1977 SC 1569 at 1575.

AIR 1977 SC 1569 at 1575.

. Tilak Ram v. Maya Devi, 1977 (1) RLR 645.

|. Tilak Ram v. Maya Devi, 1977 (1) RLR 645.

. Ibid.

Kanta Goel v. B.P. Pathak, 1977 RC] 735: 1977 Raj LR 49; K.R. Nambiar v. S.C. Mittal, 1977(1)

RCJ 907 Del: AIR 1978 Del NOC 44.

7. Attar Kaur v. R.N. Gupta, 1978(1) RLR 61 Del.

aaRoen

y

al Control of Eviction of ‘1p

ow

nant 563

as been held that the allottee will be the ¢

sprained on hie purchase from DDA under betta of the house which he

pase ement and Disposal of Housin

ng, Estate

ans 1 Estates) Regulations, 1964

dlord may be the real owne:

The jan ner but the house

ndent . se may stand e name of

ris wile oe lent child benami for him, inasmuch i. a ‘i ve

7 e Ss el i ‘ = a uch a case

cove a chi Sar ‘ tion Sa own name or in the name of his wife o

pel ap, e

Ue yas in name. ipply where they are the owners, in fact

Thi Development Authority

the Delhi High Court view has been dissented from by the Punjab and

vyna High Court.) Successor of i

Hath tof the section’ the original landlord is entitled to the

_ S 44A(1)—Being a person in occupati wags

accommodation —Actual Occupation is ne one ‘he ses

rat the landlord never lived in Government accommodation and that he lived

a house 0 Kamila Nagar. Leave to defend was granted.® The application will

not lie if he has already vacated Government premises.6 A mete allotment of

1 nmodation not followed by actual occupation i nt sufficient”

7.8. 14A(I)—Is required to vacate in pursuance of an order of the Central

Government or authority —The section will not apply where the allottee was

otherwise bound to vacate Government premises for other reasons such as

retirement from service or transfer from Delhi The Supreme Court held that

the provision applies to a person who is in Government service at the time of

the notice to vacate and retires subsequently, but not to one. who has already

retired or been transferred outside Delhi.? In Nihal Chand’s case the Supreme

Court was concerned with a case in which the Government servant had retired

after service of notice for vacating the premises, and the question as to what

would be the position in a case where the notice was served after retirement of

the Government servant did not directly arise. It arose in the case of B.N.

Muttoo v. TK. Nandi.'© The Court observed that on the reasoning of Nihal

Chand’s case the landlord would fail, but it proceeded to hold that there was

_____—

1. Kanwal Kishore Chopra v. O.P. Diwedi, 19772) RLR 274 1977(2) RCJ 320; Swaran Singh v.

Kul Bhushan, 1978(1) RLR 548 Del

CL Seth v. Deoki Nandan, 1977 Raj LR 110; Tilak Ram v. Maya Devi, 1977 Raj LR 34.

Dilbag Rai v. Lajwanti, 1977(2) RC] 135 on S. 13A(1) added in the Punjab Act in its

application to the Union Territory of Chandigarh,

| VIL. Kashyap v. RP. Puri 1977(1) RLR 397: 1977(1) RC} 47: ILR 1977(1) Del 22.

Fateh Singh v. Hukam Chand, 1977 (2) RCR 165: 1977 RLR 244,

Busching Schmitz v.P.T. Menghani, AIR 1977 SC 1569,

Om Parkash Gupta v. Ram Nath Gupta, 1976 RC) 780: 1977 RLR 496.

Ram Chander v. Gokul Chand, 1977(1) RC) 1.

Nihal Chand v. Kalyan Chand, AIR 1978(1) SC 2!

1978(2) SCR 183.

AIR 1979 SC 460.

59 (265): 1978(1) RCR 223: 1978 Raj LR.100:

10.

564 Law of Rent Control in Detht [Sec. 14,

no reason to restrict the plain meaning of the words used in the statute. The

Court said:!

The Court has to determine the intention as expressed by the word.

used. If the words of statutes are themselves precise and unambiguous

then no more can be necessary than to expound those words in their

ordinary and natural sense. The words themselves alone do in such a

case best declare the intention of the lawgiver. Taking into account the

object of the Act there could be no difficulty in giving the plain

meaning to the word ‘person’ as not being confined to Government

servants for it is seen that accommodation has been provided by the

Government not only to Government servants but to others. In the

circumstances, the Court cannot help giving the plain and

unambiguous meaning to the section. It may be that the retired

Government servants as well others who are in occupation of

Government accommodation may become entitled to a special

advantage, but the purpose of the legislation being to enable the

Government to get possession of accommodation provided by them

by enabling the allottees to get immediate possession of the residential

accommodation owned but let by them, the Court will not be justified

in giving a meaning which the words used will not warrant. On this

question therefore we find ourselves unable to concur with the view

taken by the High Court.”

It was held that the appellant wi

appeal was allowed with costs. Thus,

case do not hold the field.

Continued occupation of Government accommodation till the date of the

application is not necessary.? The matter was considered by the Supreme

Court in Narain Khamman v. Parduman Kumar Jain? and it stated its conclusions

in the form of propositions, which are teproduced below:

“18. To summarise our conclusions:

as entitled to invoke S. 14A(1) and his

the contrary observations in Nihal Chand

———____

1. BN. Muttoo v. T.K, Nandi, AIR 1979 sc 460 at 465.

2. Basheshar Nath Setia v. PC. j

AR DONS tia v. Tandon, 1980 (17) DLT 202: 1980 Raj LR 49; 1980(1) RLR 120:

3. AIR 1985SC 4 in para 18; 1985(1) SCC 1; 1985(27) DLT 35.

Control

. val of Eviction of Tenants

565

hen he files i

wn at ‘Control A es under S. 14A (1) of the

l , , to re Pt

residential premises which he so PaSeR eT has be sie

Sa r ich has been let by

Q) such person has, newever, other premises which he owns either

or in tl is wii

See ve name of his wife or dependent child

into which he h;

application under S. 144 (1) of the Act.

() Even i the other Premises owned by him either in his own name

or int fants of his wife or dependent child are not reasonably

suitable for his accommodation, he cannot maintain an application

under S. 14A (1) but must fil

ar le an application on the ground

specie in clause (e) of the Proviso to sub-section (1) of Lan of

(8S 14A(1)—Purpose of letting is irrelevant but accommodation must be

residential —It is established by a series of decisions of the Supreme Court

that the purpose of letting is irrelevant for attracting S. 14A. One may refer to

the undernoted decisions.! No teference, therefore, needs to be made tn the

High Court decisions in which the same view was taken.

The same view has been taken by the Supreme Court in regard to

interpretation of the subsequently inserted provisions contained in Ss. 14B,

14C and 14D?

Even though the purpose of letting is irrelevant, the premises sought to be

got vacated must be ‘residential accommodation.’ Krishna lyer, J. laid down

what is meant by this expression in Busching Schmitz case. The learned judge

explained the meaning of this expression in three short paragraphs so

beautifully that it almost appears to be a picture of what ‘residential

accommodation’ is. It is not necessary to reproduce here the entire discussion.

The test was laid down in para 18 in these words:

-wauu.Whatever is suitable or adaptable for residential uses, even by

making some changes, can be designated ‘residential premises’. And

once it is ‘residential’ in the liberal sense, S. 14 A stands attracted.”

The proviso to S. 14A(1) uses the expression ‘dwelling house’. In the context

it is obvious that the expression ‘dwelling house’ has been used in the same

sense as ‘residential accommodation’. An exhaustive discussion, with

1. Busching Schmitz (P) Lid. v. P-T. Menghani, AIR 1977 SC 1569; BIN. ‘Muttoo v. T.K. Nandi,

eee 3; Chander Mohan v. Harwant

. Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India, 1991(1) RCR 347 SC 12, 13; ler in v. Harwari

Singh 1994(54) DLT 12: 1994(1) RC] 545: 1994(2) RCR 24: 1994 RLR 220.

3. AIR 1977 SC 1569.

4. See paras 17 to 19 of AIR 1977 SC 1569 at 1576.

Rv

Law of Rent Control in Dethi

aw of Re

[ee 14

“ he meaning, of ‘dwelling rel '$ (0 be foung

poset OMe ac irt held:

reference a pea of the cases, the Cou

Delhi case. aka

fore, clear to me that the use of the words

“24. It is, there a it not synonymous with the word n

house’ in S. i The reason is that the allottees of Gove men

defined in the odation are not only Class IV ang Class Ij ffcer

residential accomm« ‘ing one or two room tenements in Covert

(who may be vate clude Secretaries and Joint Secretaries falling

premises), but sphere ed to live in complete bungalows, cor sisting

Sane a in addition to other @PPUrtenances a

of three or Sie intention of the amendment 1S to require them to

conveniences. t accommodation and live in their own house, it ig

aut aoa that they are Tequired to live in their Whole h,

reasonal 0 P

Ouse

ding. In other Word

remise in part of the bui rds

thei ee ee is not confined to only one Of th

eir ni

eated in the proviso and a wider expression ‘dwelling

ae inserted. The word ‘dwelling-house’ must, therefore

more extensive meaning than Premises, but another whole

be excluded from its connotation.”

ile interpreting the UP.

Which is to the same effect as S, 14A(1) and the proviso,4 The

Court also Teiterated and ©xpressly agreed

with the views of Justice Krishna

Tyer in the Busching Schmitz case,

Kashyap’s case was distinguisheg On the basis of the ob,

Supreme CourtS and j the ‘Premises let out by him’

‘an the whole building. The building in this case

been let out to four tenants. The Court Construed it to mean that the

Portion with each tenant Was ‘Premises’. It was observe that if that

1. VL. Kashyap v, Rp. Puri, 1977 Roy 47, TR 19771) Det 29. AIR 19;

2 Ibid at p. 60 of RC,

3. SS. Makhijani y. VK. Jotwani, 1997

ni, Raj LR 207: 1977 DR 880

4. SP Jain y. Krishna Mohan Gupta, AIR 1987 Hee

. 222: 1987(1 191,

5. Kanta Goel v. pp Pathak, 197713) sop 412 followeg nn

Verma, 1980(18) DLT 118,

in Nanak Chand Gupta v. Ish Kumar

77 Del Noc 205.

OF Eviction Ff Teng

: nant

commodation Was insuffic lent he

5 14()(@)-| was held that the ».

jhe right of the landlord to claim

as the landlord had been aby et pon

° LO pal

inder 5+ 14A was dismissed, © Be

u

4g, $. 4A(—Overrides the .

Prov;

under the Slum Areas (Improvement on of the Siu ,

recondition to file a petition ung, a -— Permission

he Supreme Court in Rayj p, ne the section. The roposition ey iS Rot a

te the right under ¢ Tai Sharma's case has ahent en laid down by

sublic interest and not for hig owe been conferred on the been extracted

enefi indlor h

agreement between the parties contrary at only. It has been held that an,

from enforcing his right under the Pare

was that the landlord had a

section’ Tp tO” Will not prevent him

me Pe choice to retain allo, argument before the judge

rent or ask for eviction of the tenant from hi oma eremises and pay penal

argument is that the landlord had no absol n house. The fallacy in the

accommodation on paym« 'y in the allotted

iS

‘ent of penal rent ieee

between the exercise of nl So there was no question of choice

567

Ould sue the 6

ea two tenants under

PrOVISO Was to restrict

me tenant under S. 144,

> tenants, his

adding, the

Tom only «

nf

5 petition

two rights. cs

commentary under S. 25A.

11. S. 14A(1)—Procedure for trial of a1

is laid down in S. 25B. S. 25B(1) lays down that an application under S. 14A

shall be dealt with in accordance with the procedure specified in that section.

The two grounds one under S. 14A and S, 14(1)(e) are distinct and mutually

exclusive. In an application under S. 14A the landlord must plead all the three

ingredients.” Notwithstanding this difference in the pleadings and scope of

enquiry on the two kinds of applications for eviction, the procedure for trial is

the same, i.e., as laid down in S. 25B, sub-sections (2) to (7). And in either case

there need not be specific prayer for trial under the summary procedure

n eviction petition under S. 14A.—It

Panna Lal Jain v. Memo Devi, 1983(2) RLR 186: 1983(24) DLT 66.

Sarwan Singh v. Kasturi Lal, AIR 1977 SC 265; Madan Lal Gupta v. Ravinder Kumar, 2001(1)

SCC 252: 2001 (1) JT 123 SC; Ravi Dutt Sharma v. Ratan Lal Bhargava, AIR 1984 SC 967;

Shafait Ali v. Shiva Mal, 1987(3) SCC 728: 1987 Raj LR 470.

See commentary under heading 3 supra.

Geoffery Manners and Co. v. Harbhagwan Singh, 1984(2) RC} 384: 1984(26) DLT 404: 19842)

RCR 302 Del.

International Building & Furnishing Co. v. J.S. Rikhy, 1985(2) RCR 2 2s a iB 81

. JL. Paul (Dr.) v. Ranjit Singh, 1980(18) DLT SN 24: 1980(2) RCR 52’ BRR but

Hari Mohan Nehru v. Rameshwar Dayal, 1980 Raj LR 249: AIR 1980 :

: ol :

284.

- 17; J.L. Paul (Dr.) v. Ranjit Singh,

AIR 1977 SC 265 - para 17; anit

: ‘008 aa SN Seana RCR 527; Krishan Kumar v. R.C. Dhingra, 1980 Raj

Law of Rent Control in Delhi

568 Ie. 144

Defences open in an eviction application under s 1

Dieter ated cele eas

the landlord, The defences on merits in such ae renin only 4,

fulfilment ot otherwise of the conditions an res retions mentio in 5.14

above, apart from any defence of a procedura atur pili ray available

according, to law.! In many cases an aaa of S 14(1)(0). However, Pitan

under S. 14A must also satisfy requirements of 5. F ee fever, it is row

settled that not only S. 14A but Ss. 14B, 14C an are different from

cca and confer special rights and a tenant may Pes such application,

only on the grounds specified within the respective sections.

13. S. 14A(1)—Leave to defend a petition under the section.—It is Obvious

that defences open to a tenant in an application under S. 14(1)(e) are not Open

to him. He can contest it only on the ground that the landlord 1s Not a person

in occupation of residential premises allotted to him by the Centraj

Government or that no general or special order has been made by the

Government requiring him to vacate such residential accommodation on the

terms specified in the section. Leave to defend an application under S. 14A(1)

cannot be said to be analogous to the provisions of grant of leave to defend as

envisaged by the Civil Procedure Code, Order XXXVII.

14, S. 14A(1)—Applicability of S. 14(6) and S. 14(7).—S. 25C(1) Temoves

the restriction imposed by S. 14(6) in case of persons who satisfy the

requirements of S. 14A. This means that the restriction imposed therein would

apply only in case of application made under S14(1)(e)-

By virtue of S. 25C(2) the period prescribed by S. 14(7) is reduced from 6

months to 2 months. The reason is that otherwise an applicant under S. 144

would be entitled to possession immediately.> But this is not correct in view of

the decision in Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India,® and the Controller can give

reasonable time to vacate the premises to the tenant.

15. S. 14A(1)—Applicability of S. 19(1).—S. 19(1) of the Act lays down that

where a landlord recovers possession of any premises from a tenant under

Ss. 14(1)(e), 14A, 14B, 14C and 14D, he shall not within three years from the

date of obtaining possession re-let whole or part of the premises without

permission of the Controller. The reference to Ss. 14A, 14B, 14C and 14D has

been added only by the Amendment Act 57 of 1988. However, even when

there was no reference to it in S, 19(1), the Supreme Court had held

+ Vil. Kashyap v. RP. Puri, 1977(1) RC} 47: ILR 1977(1) Del 22,

2. BN. Muttoo v. T.K. Nandi, AIR 1979 SC 460; Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India, 1991(1)

RCR 347 SC,

3. BN. Muttoo v. T.K, Nandi Supra; Busching Schmitz v. P.T. Menghani, AIR 1977 SC 1569 -

reiterated in Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India supra.

+ See B.N. Muttoo v. TK. Nandi, AIR 1979 SC 460 at 467-68.

. Ibid at p. 468.

6. Supra,

ae

moval of Renctiam of Trees

wu wee en

week! Apply evn IN relation ty 65

pot tw! 4A by reason of nevewary

amen

ig MACY Claim or eviction mut be home fide I ,

Supreme Court that all clai ft has beer Laie

pony tne laine for eviction of tenamte enue ie wien

heading of Chapter Tl A was also re

Teeases in which the contrary ples dhoveca le . nor this propositin

sre th Oe good Taw mn made can not be

nb ACI) Effect of modified

2 §. 4A ified ci 7

1 Sine? _Refore considering the cneaTad pia ie won pending,

r cessary to note the difference it made. By circular dated 9 7h, be

eetment decided that those Government servants who had built their

wees at (NE place of their posting within the limits of any local or adjacent

nicipality shall be required to vacate the Government accommodation

ak to them within three months from 1-10-1975. It was also provided that

if they did not vacate the Government accommodation within the stipulated

| after that period they would be charged licence fee at market rate. By

the revised circular dated 14-7-1977 the Government decided with effect from

14-1977 the restriction on allotment of accommodation to such servants would

stand modified making them eligible for Government accommodation The

rent or licence fee payable by the allottee was related to the rent the allottee

was receiving from his own house. The modification was brought about by a

notification issued by the President in pursuance of rule 45 of the Fundamental

Rules amending the Allotment of Government Residences (General Pool in

Delhi) Rules, 1963 contained in Part VIII, Division XXVI B of the

Supplementary Rules. Thus where leave had been refused by the Controller

and eviction order had been passed, the High Court took note of the

subsequent event, granted leave to defend and sent the matter back for the

tenant to take it as a ground of defence and for the Controller to consider its

effect and decide afresh the application for eviction.

The matter came up before the Supreme Court. It was held that the

modification did not amount to withdrawal of the first notification, which only

stood modified to the extent as to what rate of rent would be payable by the

Government employee, owning his own house, if he retained the allotted

premises, that is, if he failed to vacate the Government accommodation in

pursuance of the general order dated September 9, 1975 and the special order

dated December 26, 1975. An eviction petition filed before the modified order

was issued remained maintainable. The High Court's order dismissing it at the

revision stage was set aside.

mul

1. Busching Schmitz Pot. Ltd. v. P.T. Menghani, AIR 1977 SC 1569.

2. Surjit Singh Kalra v. UOI supra.

3. Balkrishan Kapur v. Fagir Chand Jain, 1978(2) RLR 682 Del.

4. Hakam Singh v. Jagat Singh, 1979(1) RC} 384: 1978(2) RCR 957: 1979(15) DLT 117: ILR

1978(2) Del 797; Mohan Singh v. Narain Das, 1978 Raj LR 3

5. Jain Malleables v. Bharat Sahay, AIR 1982 SC 71: 1982(21) DLT 134: 1982 Raj LR 138: 1962(1)

RC] 431 - overruling K.D. Singh v. Hari Babu Kanwal supre.

570 Law of Rent Control in Delhi [See in

je possession of premises to a

jt

1[14B. Right to recover immediat iy Were tne landlord

rces, etc.

bers of the armed fo!

“vn d or retired person from any armed forces a,

(a) is a aah by him are required for his own residence; or

premi

Core

Ind the

d forces who had bee

a member of any armet "il

(b) in oes ie iotiald let out by such member are required f4, the

' -

residence of the family of such member,

dependent may, within one year tr

s the case may be, the _

we aoieiciesre or retirement from such armed forces OF, a8 the ca,

a the date of death of such member, or within a period of one year from

Pe of commencement of the Delhi Rent Control (Amendment) Act, 199,

whichever is later, apply to the Controller for recovering the immediate

possession of such premises.

(2) Where the landlord is a member of any of the armed forces and hag 2

period of less than one year preceding the date of his retirement and the

premises let out by him are required for his own residence after his Tetirement,

he may, at any time, within a period of one year before the date of his

retirement, apply to the Controller for recovering the immediate possession of

such premises.

(3) Where the landlord referred to in sub-section (1) or sub-section (2) has

let out more than one premises, it shall be open to him to make an application

under that sub-section in respect of only one of the premises chosen by him.

Explanation— For the purposes of this section, ‘armed forces’ Means an

armed force of the Union constituted under an Act of Parliament and includes a

member of the police force constituted under Section 3 of the Delhi Police Act,

1978 (34 of 1978).

14C. Right to recover immediate Possession of premises to accrue to

Central Government and Delhi Administration employees.—(1) Where the

landlord is a retired employee of the Central Government or of the Delhi

Administration, and the premises let out by him are required for his own

residence, such employee may, within one year from the date of his retirement

or within a period of one year from the date of commencement of Delhi Rent

Control (Amendment) Act, 1988, whichever is later, apply to the Controller for

Tecovering the immediate possession of Such premises.

(2) Where the landlord is an employee of the Central

Delhi Administration and has a period of less than one

of his retirement and the Premises let out by him are Fequired by him for his

own residence after his tetirement, he may, at any time within a period of one

year before the date of his retirement, apply to the Controller for recovering the

immediate possession of Such premises.

Government or of the

year preceding the date

—_—__

1. Ins. by Act 57 of 1988, sec. 9 (wef 1-12-1988),

ws) Control of Lvtction of Tenant

Gee

.q) Where tho landlord referred to IN Sub-section (1) or exp« ,

as (ot oul more Ha ONG premises, it Shall be open here a

It eation under thal Sub-Socton i’ agryny Only one of the proneasn

chosen PY ul anes

ht to recover Immediat

44D. Rig! © Possession of premise t

dow. —(1) Where the landlord isa widow and the pras68 tt by ho

her husband, are required by her for her own

the Controller for recovering the immediate posses

2) Where the landlord referred 0 in sub-secti

ae lon (1) has let out more than

one premises, it snall be open to her to make an application under that sub-

section in respect of any one of the Premises chosen by her)

put by her, or

fesidence, she may apply to

'SION of SUCH premises

SYNOPSIS

4. $8. 14B, 14C and 14D—Iintroduction

2, $8. 14B, 14C and 140— Validity

3, Ss, 14B, 14C and 14D—Procedure to be fc

spalleatons thereundes lollowed for trial of eviction

Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Claim under must be bona fide

. $8, 14B, 14C and 14D—Applicabitity of s, 19

. $8. 148, 14C and 14D—Applicabitty of & 14(6) and S, 14(7)

. $s. 14B, 14C and 14D—Landlord need not be the owner

. Ss. 14B, 14C and 140—Purpose of letting is Irrelevant b

be suitable for residence 8 . Mt premises must

. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Transteree landlord cannot invoke

). Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Detences ‘open to the teriant

11, S,14B-Scope

12, S, 14B—Meaning of retirement

13. S.14C—Scope

14, S.14C—Leave to defend

15. S.14D—Scope

Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Introduction.—These three sections have been

inserted in the Act for the first time by the Amendment Act of 1988. They are

intended to confer special rights for tecovery of immediate possession of their

premises on defined categories of landlords, in case they require the same for

their own residence. The categories of these landlords are three: (1) Landlord

who is released or retired person or a person due to retire from any armed

force, i., armed force of the Union constituted under an Act of Parliament or

the police force constituted under S. 3 of the Delhi Police Act, 1978;

(2) landlord being retired employee or employee due to retire from service of

the Central Government or of the Delhi Administration; and (3) landlord who

isa widow.

Law of Rent Control in Deth [Ser 14R

Certain common features

(the three sections is quite similar Certain i

The wording of the Firstly, all the three sections refer tq

e noted

in the three sections may be not

Se he sections the basic condity

\ rd and not the owner Secondly, in allt i

; h ; hi st be for ‘own residence’ In case

is that the requirement of the landlord must be f ver of arined a of

Sua requirement may also be of the family of the member of armed force:

require ay

pose ptting nor the nature of premises js

refered ie bli icobrous thal the premises fa question must be ulabe ye

ee Baad wholly commercial premises would be outside the sections

Thin thy in “tthe three sections a period of limitation of one year is prescribed

for invoking the section from the date of accrual of the cause iM action a in

case of the employees ete. of the armed forces or Government joned in

Ss. 14B and 14C, the landlord may invoke the section upto one year prior to

the due date of retirement. Fourthly, in all cases an option has been Biven to

the landlord to choose one premises, where he has let out more than one

Premises, for the purposes of invoking the requisite section. He cannot invoke

the section in respect of more than one premises. At the same time, his choice

of one premises cannot be questioned, provided of course the Premises are

suitable for residence.

Simultaneously with the insertion of Ss. 14B to 14D, S. 25B(1) of the Act was

also amended to provide that the applications under Ss. 14B to 14D would be

dealt with in accordance with procedure specified in S. 25B. S. 19(1) was also

amended. But no amendments were made in S. 25B sub-secs. (2) to (5).

Though the sections are comparatively new, several aspects related to their

validity and interpretation have been authoritatively settled. We shall first

refer to the common points and then the specific sections in this respect.

2. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Validity—The validity of the sections was

challenged on the ground of violation of Art. 14 of the Constitution. It was

submitted that the classification made by these sections was arbitrary,

discriminatory and illegal. The challenge was rejected and it was held that it

was a matter of legislative policy if it felt that Particular sections of landlords

should be allowed to recover Possession of their premises from tenants in a

faster and easier manner. It was irrelevant that all the deserving categories of

the landlords had not been given similar benefit!

3. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Procedure to be

applications thereunder—The question was

B.M. Chanana v. Union of India? by a divisi

Relying on the fact that by the Amendment

—_____

1. BM. Channa v. Union of india, 1990(1) RCR 312 Del DB: : ;

"3300 RR mane) RCJ 219: 1990(40) DLT 113,

. Kapur (Dr) v. Union of India

: RCI ; 4

Union ofa, BIO) ROR a ee need on another pone Singh Kalra v.

417: 1991(2) SCC 87:

Sec. 14B]

Control o

Ml Eviction of Tenant

amended, but the other

not amended, it was ur

down in S. 25B would

sub. Section

20 S thereof an,

ed betore the Cour an a

Sh apply to such ot

~C Applications

me T Menetted 10 the Supreme Cone von

Wd Vv. > Menghani! j @ecision in Busch

“ Nas bee: ae

Viction under ¢ os een held tha

ond ele that aes As even though ene oe Hat: 19 applied ever

and a at despite the omission by the L seen erence to S '4A in. 19,

of S. 25B except sub-sec.(1) ~Cgislature to amend the Provisi

Schedule, it was obvious th; mend form ¢

‘a .

Ss. 14B, 14C and 4p ce ih of Legislature was that cases under

10us]

id be i. *

summary procedure lain down i my disposed of and therefore the

der Ss. 14B, 14C - “9B would apply to evict es

unde of summons ‘would There was no difficulty in tis peceinene

ave to be adapted by Mserting the relevant

as taken the same view, though

urt judgment. The Court observed

Purpose and object of classification

ecified rights to recover immediate

cd nugatory3

ve form of sure nONS w

"SUMMArY procedure laid

of summons in the

‘asses with sp

possession of premises would be rendere

so.’ Contrary observations in some earlier cases are not good law. But even in

Dr. P.P. Kapur’s case the bench had held that mere desire of the landlord was

not enough, and there must be an element of need in it. The tenant can not be

evicted on a false plea of requirement or

feigned requirement.6

5. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Applicability of S. 19.—It

including these sections by amendment by Act 57 of 1988,

6. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Applicability of S. 14(6) and S. 14(7).—They do

not apply. The reader may refer to the commentary under those sections. Also

see commentary under heading No. 9, infra.

applies by specifically

Though S. 14(7) does not apply, it does not mean that the tenant is not

entitled to any time for surrendering possession of the premises. It is always

left open to the Controller, who is a quasi judicial authority, to exercise his

judicial discretion in every case of eviction, and grant reasonable time to the

; vcae 7

tenant to deliver possession of premises.

1. AIR 1977 SC 1569.

2. Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India, 1991 (2) SCC 87.

3.\ Ibid. para 8. ; »

4, Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India supra para 20. o

5. P.P. Kapur (Dr.) v. Union of India, AIR ee ae etc

ic |. v. Rajendra K. Tandon,

6. Rahabar Productions Put. Ltd. v.

7. Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India supra para 21.

7. Law of Rent Control in Delhi Ge

574 aw of [er in

In this connection it may be noticed that the Delhi High Court hag

the Controllers to give two month’s time for vacating, the premis

cases.' In view of the Supreme Court decision, the Controller can ary thy

time according to the circumstances of each case. But itis obvious thar ihe

should not exceed very much beyond the period of two-three months, j

of the fact that even in a case under S. 14(1)(¢) the maximum time allowed i.

six months. These being provisions for immediate recovery of POSSESSion, the

time allowed should be at least lesser than that in cases under S, 14(1 Ne)?

7. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Landlord need not be the owner.— Ajj the thes

sections use the word ‘landlord’. Accordingly the landlord need not be aso the

owner of the premises in question, as in the case of an eviction PPlication

under S. 14(1)(e).

8. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Purpose of letting is irrelevant but Pre:

must be suitable for residence.—So far as the first part of the Proposit

concerned, it is settled by decisions of the Supreme Court.’ The same vie:

been taken by the High Court. The reader may also refer to comm,

under S. 14A whereunder the legal position is the same.

Stroy

Mall sug

N View

Mises

tion is

"Ww had

lentary

The second part of the proposition is implicit in the sections. As alread

observed all the sections~provide for immediate recovery of Possession of

premises in case of requirement for ‘residence’ either of the landlord, or his

family in case of a landlord who, being a member of the armed forces, was

Killed in action. It follows a fortiori that the premises must be such which are

suitable for residence. Thus it is submitted that the word ‘premises’ in these

sections will have the same meaning as has been given to the words

‘residential accommodation’ used in S. 14A. The test laid down by Krishna

yer, J. in Busching Schmitz case® would be applicable. For that again the reader

may refer to the commentary under S. 14A. In Mahendra Raj's case the Court

observed that if premises are residential in nature the purpose of letting would

be irrelevant, meaning thereby that the premises must be residential in nature.

It is submitted that the test laid down in Busching Schmitz case is more

appropriate.

\

9. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Transferee landlord cannot invoke.—In BM.

Chanana v. Union of India’ question arose before the High Court as to whether a

transferee landlord or the successor-in-interest of the original landlord had a

right to invoke S. 14C. The Court referred to V.L. Kashyap’s case” and Kanta

L

B.M. Channa v. Union of India supra and Mahendra Raj v. Union of India, 1990(2) RCR 63 DB.

Mahendra Raj v. Union of India, 1990(2) RCR 63 Del DB affirmed in Surpit Singh Kalra v.

Union of India, 1991(1) RCR 347 SC; P.P. Kapur (Dr.) v. Union of India, AIR 1990 Del 290.

Furit Singh Kalra v. Union of India supra; EMC Steels Ltd. v. Union of India, 1991()

RCR 407.

n

P.P. Kapur (Dr.) v. Union of India, AIR 1990 Del 290.

AIR 1977 SC 1569.

- 1990(1) RCR 312 DB.

TLR 1977(1) Del 22.

nage

. 14B \

sec. 148] Control of Futction of

of Tenant

, 1

Goel’s case! and held that the expre:

premises of which he was the ndlong

‘Premise: let

we landlord nt § Wet out by ir

when application for eviction Was filed the date of retirement aia mean

‘ourt express 5 ‘d, in case ‘e time

The Cc 7 Pp essed the view that it would Nis filed before his Tetirement

object of enacting §. 14c if 4 “tbe defeating the Purpose

expressed the conclusion, Strictive me, Poegiand

there;

landlord either by inheri crefore, that where

5 eritance oO

occupation thereof under that landlord 7

or when he filed an application under ‘ate of the land)

premises were let out }: aoe

we . Y the land

maintain the said application.2 The cout i in position to

apply to a case under S. 14C, 9¢ ; wither held that s

i 5, f the heirs

my was e1 tit ? one o| on

against the tenant who was inducted by tie hei a h their agen sete

held that the premises were aa

’ Us eir agent. It w:

1 v a ‘ough th gent. It was

This matter also cam

€ up before thy i ‘it Si

Union of India It was urged bef ae upreme Court in Surjit Singh Kalra v.

oe Supreme Court that S. 14(6) was als

attracted to applications 14C and 14D. The Court re

“The original landlord who cannot evict the tenant since he has got

Many houses under his Occupation cannot use the device by

transferring one of the houses to a third party who could easily evict

such a tenant. The tenant in occupation of the transferred premises

gets a protection from eviction for a minimum period of five years.

S. 14B and other allied provisions referred to the premises let out and

not acquired by transfer. One may become an owner of the premises

by transfer but the tenant in occupation of the transferred property

cannot be evicted by resorting to Ss. 14B to 14D. If the transferee wants

to evict the tenant of such premises he must take action only under

S. 14(1)(€)..00..”

(Emphasis supplied)

1. AIR 1977 SC 1599. :

° ees age fon bur 2 eer 1994(2) RCR 24: 1994

994(54 :

3. Chander Mohan v. Harwant Singh, 1

RLR 220,

4. 1991(1) RCR 347.

5. Atp. 353 para 21 of the RCR.

Law of Rent Control in Delhi See. 14R

576

: » Supreme Court judgme,

squence of the sent ig

. at the consequ Pre met e naeE

It is therefore cle et high Court i Raiciamama men

gment of the

that the judgmen

ent sath

overruled to this exte far as the Supreme C ‘ourt has held r at S. 14(6) has

It is submitted that so fa na aD, here can De no aut “1

¢ inder Ss.

ications Ww servations in Sarwan Singh

application to app h there are some obs i v

this proposition, even et but for S. 25C the provisions of S. 14(6) could

Kasturi Lal' which sugges case under S. 14A, and on parity of Teasoning to

have ns applicable ° ne This is because S. 14(6) expressly refers to

cases under Ss. ;

nae 4(1)(e).

application for eviction ey . ' Oe eee landlord cannot invoke Ss. 145

However, the proposition al : ears, with respect, to be too wide, The

to 14D under any Se eee BM. Chanana’s case appears to be

aed eat aa cononanee with the statutory provisions. The High

eet ie ‘Tightly observed that in principle no distinction ean ibe made

between S. 14A and the sections under consideration in respect o Tansferee

landlord. The Supreme Court appears to have proceeded on an assumption

that it is very easy to transfer houses to persons who can take benefit of the

sections under consideration and thereby summarily evict the tenants. It is

submitted that there is no foundation for such an assumption. In the first place

it is not so simple to transfer residential houses merely with intent to evict the

tenant, and that too to a category of landlords covered by the sections under

consideration. Secondly, even if a transfer is made simply to invoke the

sections under consideration, it would always be open to the tenant to show

that the transfer was mala fide or sham with the intention of simply evicting the

tenant in occupation. Thirdly, by reasoning of this interpretation many

deserving landlords would be denied the right of invoking the section, For

example, a member of the armed forces may genuinely purchase a house

occupied by a tenant with the intention of Occupying it at some future point of

in action soon after the purchase. This

een and there is no reason as to why in

many instances of en nat to invoke S. 14B. There may be

expression “let oA

“Tet out by her, out by him” in Ss, 145 and 14C and

or by as

1 AIR 1977 5¢ 265 (274), Y her husband” in S. 14D have

2. 2004 (10) SCALE 550,

sec. 14B]

Control of Eviction of Tenant S77

significance. If it was unnecessary in the scheme of these Sections as to

who had actually let out the premises, the legislature would not have

used the term “let out by him” or ‘let out by her, or by her husband”

In interpreting, a provision one cannot assume that the words employed

by the legislature are redundant. ”

The expression, “let out by her or by her husband” is not an

expression which permits of any ambiguity. We must, therefore, give it

its normal meaning. So understood the conclusion is inescapable that

the legislature intent was only to confer a special right on a limited class

of widows viz. the widow who let the premises or whose husband had

let the premises before his death and which premises that widow

requires for her own use.”

It was further held that if Ss. 14(6) and 14D were not read harmoniously,

it would lead to an anomaly. Such anomaly can be removed by holding that

since a transferee landlord cannot evict a tenant before expiry of 5 years from

date of purchase, S. 14D providing for immediate recovery of premises would

not be applicable to such a case.

10. Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D—Defences open to the tenant—Since the

procedure laid down in S. 25B applies, the tenant has to obtain leave to defend

under S. 25B(5). The scope of S. 25B(5) has been considered in detail later and

reference may be made to the commentary thereunder.

The question which would survive for consideration is as to what are the

defences open to the tenant under Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D. The matter is no

longer res integra and has been examined and settled by the decisions of the

Supreme Court as also the Delhi High Court.

In Surjit Singh Kalra v. Union of India,’ which was a case under S. 14B, it was

argued on behalf of the tenants that the tenant would be entitled to leave to

contest an application under Ss. 14B, 14C and 14D by disclosing such facts as

would disentitle the landlord from obtaining an order of eviction on grounds

specified in S. 14(1)(e).

The Court compared the provisions in S. 14(1)(e) and in S. 14B, and after

observing that Ss. 14C and 14D were similar to S. 14B, it came to the

conclusion that ‘Ss. 14B to 14D were markedly different from S. 14(1)(e).’ It,

then referred to the statutory provisions in S. 25B and the form of the

summons in the Third Schedule and repelled the argument of the tenants in

these words:?

If the application is filed under S. 14B, the summons should state

that the application is filed under S. 14B and not under S. 14(1)(e) or

14A. Likewise if the applications are under Ss. 14C to 14D, the

summons should state accordingly. That would indicate the scope of

the defence of the tenant for obtaining leave referred to in sub-section

(5) of S. 25B. Under sub-section (5), the tenant would contest the

application by obtaining leave with reference to the particular claim in

—___

1. 1990 (1) RCR 347 SC.

2. Ibid p. 352.

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- N:fffi: - Lrai"iDocument5 pagesN:fffi: - Lrai"iRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- The Rules To Regulate Proceedings For Contempt of The Supreme Court, 1975'Document5 pagesThe Rules To Regulate Proceedings For Contempt of The Supreme Court, 1975'Rahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Retrial: Section 386 (B) of The Criminal Procedure Code, 1973Document6 pagesRetrial: Section 386 (B) of The Criminal Procedure Code, 1973Rahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Research Diary Entry - Sahitya SrivastavaDocument4 pagesClinical Research Diary Entry - Sahitya SrivastavaRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Seminar - I (Synopsis)Document9 pagesSeminar - I (Synopsis)Rahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Sample ProjectDocument22 pagesSample ProjectRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Relinquishment DeedDocument7 pagesRelinquishment DeedRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Project of Environmental LawDocument24 pagesProject of Environmental LawRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Implied Limitations O N Amendments: Submitted byDocument21 pagesImplied Limitations O N Amendments: Submitted byRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Social Media and Freedom of Speech and ExpressionDocument16 pagesSocial Media and Freedom of Speech and ExpressionRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Appointment of CommissionerDocument5 pagesAppointment of CommissionerRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Family Law New AssignmentDocument15 pagesFamily Law New AssignmentRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Code OF Criminal Procedure IDocument27 pagesCode OF Criminal Procedure IRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Mortgage DeedDocument10 pagesMortgage DeedRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Setting Aside of Ex - Parte OrderDocument5 pagesSetting Aside of Ex - Parte OrderRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Examination Paper - Admin Law May 2020Document3 pagesExamination Paper - Admin Law May 2020Rahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Hindu Law. Raghib Naushad PDFDocument96 pagesHindu Law. Raghib Naushad PDFRahul GuptaNo ratings yet