Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Materi Jurnal TB-2 - 9

Materi Jurnal TB-2 - 9

Uploaded by

rfmwddh 130 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views5 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views5 pagesMateri Jurnal TB-2 - 9

Materi Jurnal TB-2 - 9

Uploaded by

rfmwddh 13Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

CASE STUDY 2 + DISNEYLAND RESORT PARIS 369

than Florida were allayed by the spectacular success of Disneyland Tokyo in a

location with a similar climate to Paris. The first letter of agreement was signed

with the French government in December 1985, and financial contracts started

to be drawn up during the following spring. Robert Fitzpatrick, a key organiser

of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, was appointed as the Euro Disney President,

and construction started on the 2,000 hectare site in August 1988. But from the

announcement that the park would be built in France, it was subject to a wave

of criticism. One critic called the project a ‘cultural Chernobyl’ because of how

it might affect French cultural values. Another described it as ‘a horror made of

cardboard, plastic, and appalling colours; a construction of hardened chewing-gum and

idiot folk lore taken straight out of comic books written for obese Americans’. However,

as some commentators noted, the cultural arguments and anti-Americanism

of the French intellectual elite did not seem to reflect the behaviour of most

French people, who ‘eat at McDonald's, wear Gap clothing, and flock to American

movies’.

The major advantage of locating in Spain was the weather. However, the even-

tual decision to locate near Paris was thought to have been driven by a number

of factors that weighed more heavily with Disney executives. These included the

following:

© There was a site available just outside Paris that was both large enough and flat

enough to accommodate the park.

‘© The proposed location put the park within a two-hour drive for 17 million people,

a four-hour drive for 68 million people, a six-hour drive for 110 million people and

a two-hour flight for a further 310 million ot so.

‘© The site also had potentially good transport links. The Euro Tunnel that was to

connect England with France was due to open in 1994. In addition, the French

autoroutes network and the high-speed TGV network could both be extended to

connect the site with the rest of Europe,

© Paris was already a highly attractive vacation destination and France generally

attracted around 50,000,000 tourists each year.

‘© Europeans generally take significantly more holidays each year than Americans

(five weeks of vacation as opposed to two or three weeks)

© Market research indicated that 85 per cent of people in France would welcome a

Disney park in their country.

‘© Both national and local government in France were prepared to give significant

financial incentives (as were the Spanish authorities), including an offer to invest

in local infrastructure, reduce the rate of value added tax on goods sold in the park,

provide subsidised loans and value the land artificially low to help reduce taxes.

Moreover, the French government were prepared to expropriate land from local

farmers to smooth the planning and construction process.

‘The resort was to be 49 per cent owned by the Walt Disney Company and 51 per cent

owned by a company called Euro Disney SCA, which was quoted on the French stock

exchange. Initially all shares were offered to European investors. The Walt Disney

Company was to receive management fees and royalty fees based on the park's

revenues as well as an incentive-based management fee calculated on the park's

cash flow.

370 CASE STUDY 2 * DISNEYLAND RESORT PARIS

Designing Disneyland Resort Paris

Phase 1 of the Euro Disney Park was designed to have 29 rides and attractions as well

as six hotels with over 5,000 rooms in total. In addition, the park had a championship

golf course together with many restaurants, shops, live shows and parades. Although

the park was designed to fit in with Disney’s traditional appearance and values, a

number of changes were made to accommodate what was thought to be the prefer-

ences of European visitors. For example, market research indicated that Europeans

would respond to a ‘wild west’ image of America. Therefore, both rides and hotel

designs were made to emphasise this theme. Disney was also keen to diffuse criti-

cism, especially from French left-wing intellectuals and politicians, that the design

of the park would be too ‘Americanised’ and would become a vehicle for American

‘cultural imperialism’. To counter charges of American imperialism, Disney gave the

park a flavour that stressed the European heritage of many of the Disney characters,

and increased the sense of beauty and fantasy. They were, after all, competing against

Paris's exuberant architecture and sights. For example, Discoveryland featured sto-

rylines from Jules Verne, the French author. Snow White (and her dwarfs) was located

in a Bavarian village. Cinderella was located in a French inn, Even Peter Pan was made

to appear more ‘English Edwardian’ than in the original US designs.

Disney conceded to the pressure for French to be the language of the park with

English taking second place, The American actor Vincent Price’s voice-over for the

Phantom Manor, that was used initially, was replaced by a French actor. Only Price's,

maniacal laugh remained. In keeping with their desire to make this park more

‘European’, even the story behind the Disneyland Paris Phantom Manor (named The

Haunted Mansion in the US versions), although open to interpretation, was changed

to include bits of The Phantom of the Opera and Great Expectations, Main Street USA,

built in the idealised style of America at the beginning of the twentieth century, con-

tained ornate shopping arcades one of which (diplomatically!) contained an exhibi-

tion telling the history behind the presentation of the Statue of Liberty by France to

the USA in a spirit of friendship.

Because of concerns about the popularity of American ‘fast-food’, Euro Disney

introduced more variety into its restaurants and snack bars, featuring foods from

around the world. In a bold publicity move, Disney invited a number of top Paris chefs

to visit and taste the food. Some anxiety was also expressed concerning the different

‘eating behaviour’ between Americans and Europeans. Whereas Americans preferred

to ‘graze’, eating snacks and fast meals throughout the day, Europeans generally pre~

ferred to sit down and eat at traditional meal times. This would have a very significant

impact on peak demand levels on dining facilities. A further concern was that in

Europe, (especially French) visitors would be intolerant of long queues. To overcome

this, extra diversions such as films and entertainments were planned for visitors as

they waited in line for a ride,

Discoveryland was new for a Disney park; it was based on the concept of the future

based on past European visionaries, Fantasyland was also new in that it had its own

new ‘European’ attractions, along with a newly created castle especially for Euro

Disney. Adventureland gained some extra new areas, again with a more authentic

‘European’ look than in previous parks.

Before the opening of the park, Euro Disney had to recruit and train between

12,000 and 14,000 permanent and around 5,000 temporary employees. All these

new employees were required to undergo extensive training in order to prepare

CASE STUDY 2 + DISNEYLAND RESORT PARIS 371)

them to achieve Disney's high standard of customer service as well as understand

operational routines and safety procedures. Originally, the company’s objective was

to hire 45 per cent of its employees from France, 30 per cent from other European

countries and 15 per cent from outside of Europe. However, this proved difficult

and when the park opened around 70 per cent of employees were French. Most ‘cast

members’ were paid around 15 per cent above the French minimum wage.

Espace Euro Disney (an information centre) was opened in December 1990 to

show the public what Disney was constructing. The ‘casting centre’ was opened

on 1 September 1991 to recruit the cast members needed to staff the park's attrac-

tions, But the hiring process did not go smoothly. In particular, Disney's grooming

requirements that insisted on a ‘neat’ dress code, a ban on facial hair, set standards

for hair and fingernails and an insistence on ‘appropriate undergarments’ proved

controversial. Both the French press and trade unions strongly objected to the

grooming requirements, claiming they were excessive and much stricter than was

generally held to be reasonable in France, Nevertheless, the company refused to

modify its grooming standards.

Accommodating staff also proved to be a problem, when the large influx of

employees swamped the available housing in the area. Disney had to build its own

apartments as well as rent rooms in local homes just to accommodate its employees.

Notwithstanding all the difficulties, Disney did succeed in recruiting and training all

its cast members before the opening

The park opens

‘The park opened to employees for testing during late March 1992, during which time

the main sponsors and their families were invited to visit the new park. The formal

press preview day was held on 11 April 1992, and the park finally opened to visitors

on 12 April 1992. When opening the new resort, Roy Disney, nephew of Walt Disney,

spoke of his ‘emotional homecoming for the Disney family, which traced its roots to the

French town of Isigny-sur-Mer’. The opening was not helped by strikes on the commuter

trains leading to the park, staff unrest, threatened security problems (a terrorist bomb:

had exploded the night before the opening) and protests in surrounding villages

who demonstrated against the noise and disruption from the park. The opening-day

crowds, expected to be 500,000, failed to materialise, and at close of the first day only

50,000 people had passed through the gates.

Disney had expected the French to make up a larger proportion of visiting guests

than they did in the early days. This may have been partly due to protests from French

locals who feared that their culture would be damaged by Euro Disney. Also all Disney

parks had traditionally been alcohol-free. To begin with Euro Disney was no different,

However, this was extremely unpopular, particularly with French visitors who like to

have a glass of wine or beer with their food. But whatever the cause, the low initial

attendance was very disappointing for the Disney Company.

It was reported that, in the first nine weeks of operation, approximately 1,000

employees left Euro Disney, about one half of whom ‘left voluntarily’. The reasons

cited for leaving Disney's employment varied. Some blamed the hectic pace of work

and the long hours that Disney expected. Others mentioned the ‘chaotic’ condi-

tions in the first few weeks, Even Disney conceded that conditions had been tough

372 CASE STUDY 2 » DISNEYLAND RESORT PARIS

immediately after the park opened. Some leavers blamed Disney's apparent difficulty

in understanding ‘how Europeans work’. ‘We can’t just be told what to do, we ask ques-

tions and don’t all think the same’ Some visitors who had experience of the American

parks commented that the standards of service were noticeably below what would

be acceptable in America. There were reports that some cast members were failing to

meet Disney's normal service standard:

- even on opening weekend some clearly couldn't care less ... My overwhelming impres-

sion ... was that they were out of their depth. There is much more to being a cast member

than endlessly saying “Bonjour”. Apart from having a detailed knowledge of the site,

Euro Disney staff have the anxiety of not knowing in what language they are going to be

addressed ... Many were struggling’

It was also noticeable that different nationalities exhibited different types of behav-

iour when visiting the park. Some nationalities always used the waste bins while

others were mote likely to drop litter. Most noticeable were differences in queueing

behaviour. Northern Europeans tend to be disciplined and content to wait for rides in

an orderly manner. By contrast, some southern European visitors ‘seem to have made

an Olympic event out of getting to the ticket taker first’

‘The press in a number of countries debated whether Euro Disney really knew what

it was trying to be. Is it an American theme park in Europe? Is it a theme park that

exploits the European heritage of Disney characters? Had the park any connection at

all with France, its host country? Is there a fundamental difference between Europeans

and Americans in the type of entertainment that they appreciate? Is it even possible

to devise a theme park that can please so many different nationalities and cultures?

Others claimed that the nature of the European work force was such that they could

never achieve the US standards of Disney service:

‘The Disney style of service is one with which Americans have grown up. There are several

styles of service (or lack of it) in Europe; unbridled enthusiasm is not @ marked feature

of them’

Nevertheless, not all reactions were negative. European newspapers also quoted

plenty of positive reaction from visitors, especially children. Euro Disney was so dif-

ferent from the existing European theme parks, with immediately recognisable char-

acters and a wide variety of attractions. Families who could not afford to travel to the

United States could now interact with Disney characters and ‘sample the experience at

far less cost’

The first phase of development (the theme park, hotel complex and golf course)

had gone massively over budget. And attendance figures failed to improve much (by

May the park was only attracting around 25,000 visitors a day instead of the pre-

dicted 60,000). Moreover it appeared that only three in every 10 visitors were native

French. Seven weeks after the opening of the park, visitor attendance was reported

at 1.5 million, a disappointment for the park which had expected 11 million visi-

tors in its first year, and when Euro Disney announced its first quarter revenues of

$489,000,000, it also said that it would make a loss in its first financial year. Again,

the loss was blamed on disappointing attendance figures. Nevertheless, the company

pointed out that Disney’s other theme parks had made comparable losses in their

first year of operation, and anyway, it was foolish to try to predict future attendance

so early in the park’s history. However, the Euro Disney company stock price started

a slow downward spiral, rapidly losing almost a third of its value.

CASE STUDY 2 + DISNEYLAND RESORT PARIS 373

The next 15 years

By August 1992 estimates of annual attendance figures were being drastically cut from

11 million to just over 9 million. Euro Disney’s misfortunes were further compounded

in late 1992 when a European recession caused property prices to drop sharply, and

interest payments on the large start-up loans taken out by Euro Disney forced the

company to admit serious financial difficulties. Also, the cheap dollar resulted in more

people taking their holidays in Florida at Walt Disney World.

At the first anniversary of the park’s opening, in April 1993, Sleeping Beauty’s

Castle was decorated as a giant birthday cake to celebrate the occasion, however,

further problems were approaching. Criticised for having too few rides, the roller

coaster Indiana Jones and the Temple of Peril was opened in July. This was the first

Disney roller coaster that included a 360-degree loop, but just a few weeks after open-

ing emergency brakes locked during a ride, causing injuries to some guests. The ride

was temporarily shut down for investigations. Also in 1993 the proposed Euro Disney

phase 2 was shelved due to financial problems. Which meant Disney MGM Studios

Europe and 13,000 hotel rooms would not be built to the original 1995 deadline origi-

nally agreed upon by The Walt Disney Company. However, Discovery Mountain, one

of the planned phase 2 attractions, did get approval

By the start of 1994, rumours were circulating that the park was on the verge of

bankruptcy. Emergency crisis talks were held between the banks and backers, with

things coming to a head during March when Disney offered the banks an ultimatum,

It would provide sufficient capital for the park to continue to operate until the end of

the month, but unless the banks agreed to restructure the park’s $1 billion debt, the

‘Walt Disney company would close the park and walk away from the whole European

venture, leaving the banks with a bankrupt theme park and a massive expanse of vir-

tually worthless real estate. Disney then forced the bank's hand by calling the annual

stockholder meeting for 15 March. Shortly before the stockholder meeting, Michael

Eisner, Disney's CEO, announced that Disney was planning to pull the plug on the

venture at the end of March 1994 unless the banks were prepared to restructure the

loans. Faced with no alternative other than to announce that the park was about to

close, just before the annual meeting the banks agreed to Disney’s demands. This

effectively wrote off virtually all of the next two years’ worth of interest payments,

and granted a three-year postponement of further loan repayments. In return, the

‘Walt Disney Company wrote off $210 million in unpaid bills for services, and paid

$540 million fora 49 per cent stake in the estimated value of the park, as well as restru

turing its own loan arrangements for the $210 million worth of rides at the new park.

In May 1994, the train connection between London and Marne-la-Vallée was

completed, along with a TGV link, providing a connection between several major

European cities. By August the park was starting to find its feet at last, and all of the

park’s hotels were fully booked during the peak holiday season, Also, in October, the

park's name was officially changed from Euro Disney to ‘Disneyland Paris, in order

to, ‘show that the resort now was named much more like its counterparts in California and

Tokyo’ and to link the park more closely with the romantic city of Paris. Some com-

mentators noted that the name change would disassociate the resort in people's

minds with controversy, debts and politics. The end-of-year figures for 1994 showed

encouraging signs despite a 10 per cent fall in attendance caused by the bad publicity

over the earlier financial problems. And by the end of March 1995 Disney executives

were predicting that Disneyland Paris might break even by the end of 1995.

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- ToeflDocument43 pagesToeflrfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- MT Indofood Future LeaderDocument6 pagesMT Indofood Future Leaderrfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Pemasaran-Konsep Dan AplikasiDocument473 pagesPemasaran-Konsep Dan Aplikasirfmwddh 13100% (2)

- Structure: IntelligenceDocument1 pageStructure: Intelligencerfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Materi Jurnal TB-2 - 10Document5 pagesMateri Jurnal TB-2 - 10rfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Ekonomi Kemiskinan: Introducing Economic Development: A Global PerspectiveDocument33 pagesEkonomi Kemiskinan: Introducing Economic Development: A Global Perspectiverfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Materi Jurnal TB-2 - 11Document10 pagesMateri Jurnal TB-2 - 11rfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Materi Jurnal TB-2 - 12Document10 pagesMateri Jurnal TB-2 - 12rfmwddh 13No ratings yet

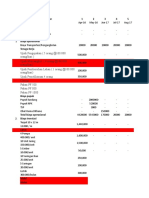

- Upah Pengepakan (5 Orang @100.000 Orang/hari) Upah Mencangkul (4 Orang @100.000 Orang/hari) Upah Pembersihan Lahan (1 Orang @100.000 Orang/hari)Document5 pagesUpah Pengepakan (5 Orang @100.000 Orang/hari) Upah Mencangkul (4 Orang @100.000 Orang/hari) Upah Pembersihan Lahan (1 Orang @100.000 Orang/hari)rfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Proposal KKN Desa BojongsariDocument15 pagesProposal KKN Desa Bojongsarirfmwddh 13No ratings yet

- Makalah Tugas Mata Kuliah Sistem Informasi BisnisDocument17 pagesMakalah Tugas Mata Kuliah Sistem Informasi Bisnisrfmwddh 1350% (2)