Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bangladesh in Oxford Encyclopedia

Bangladesh in Oxford Encyclopedia

Uploaded by

Jiaor Rahman Munshi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views5 pagesOriginal Title

bangladesh in oxford encyclopedia

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views5 pagesBangladesh in Oxford Encyclopedia

Bangladesh in Oxford Encyclopedia

Uploaded by

Jiaor Rahman MunshiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

because of their ethnic diversity (Albanians, Turks,

Macedonian Slavs, and Gypsies). During World War II

Bosnia was annexed by the puppet Croatian fascist state,

and some Bosnian Muslims joined the Ustashe terror-

ists, often against their better judgment. Both during

and after the war, ties to the Ustashe had tragic conse-

‘quences. Under the Tito regime, the situation became

even more complex. Beginning in 1960 the government

decided to favor the Yugoslav Muslim community by

granting them significant freedom of action and material

advantages. In 1967 a Muslim Nation was recognized as

one of the country’s constituent peoples, although this

recognition extended only to Muslims in Bosnia

Herzegovina, This privileged status rapidly deteri

rated, however, as ethnic and religious tensions grew

following the sharp downturn in the Yugoslav economy

and the collapse of the Communist regime. Recent

events in the former Yugoslavia have affected the three

main Muslim groups in different ways.

In Macedonia local Muslims are seeking to build

stronger ties with their non-Muslim neighbors. Above

all, they seek to free themselves from the grip of Alba-

nian Muslims from Kosovo, who continue to migrate to

western and southern Macedonia in large numbers.

In Kosovo the situation is explosive owing to the long-

standing enmity between the Serbs and the Albanians,

which was raised to a fever pitch during the Communist,

cra, It is virtually impossible to say anything precise

about the current religious situation of the Albanian

community because the assertion of Albanian national-

ism monopolizes public discourse, making it difficult to

analyze the actual influence of both the mosque and the

mystical brotherhoods.

Bosnia-Herzegovina has seen Islam politicized by the

Democratic Action Party of Alija Izetbegovié, whose

theories are clearly presented in two books, The Islamic

Declaration (1970) and Islam between East and West

(1980; English translation, 1984). Izetbegovié has

pushed the various Bosnian Muslim communities to-

ward a “holy union,” even though many of them had

previously shown little enthusiasm for any sort of reli-

gious activism. The country’s Orthodox Serbs and Cath-

olic Croats have similarly retreated into hard-line na-

tionalism, bolstered by their respective churches.

Exploited by leaders who are all former members of the

Titoist political elite, this communal division has led

to the gruesome combat that began in the spring of

1992.

[See also Albania.]

BANGLADESH 187

mIBLiooRAPHY

Caer Nate. LAlboi pa det dvs Leds mts mic

tno ov Aon Pope ps-anomane, 192-1967 Bein and

Wade, 190

Kalonty A "The Pomsk Dilemma.” In La raisin dso

dans le monde murulman périphérique, Lettre d'information, n0. 13,

bp. tat-0, Pai, 1953,

Lett, Glam in Hungary" Canal Ain Srey 1.1 (952%

3

Popo, Alexandre. Lam Blane Let muna uber

rote dan a pide prtotomane. Bein and Wiesbaden, 1986.

Provides an ove view ofthe Musi communis of Southeast

Europe, with an extensive angotatediblography aranged by

county ad perio

Popov, Alenundre, Let mactmons yugoe, 1945-1989: MAd-

tia map ase, 190

Auexavone Porome

‘Translated from French by Harry M. Matthews, Jt

BANGLADESH. The identity of Bangladesh as a

‘modern nation-state is derived from a cohesive ethnic

and regional base in which Islam has long been a key

element. Nearly all of the country’s 114 million people

are speakers of the Bengali language, and, minor sectar-

ian variation aside, some 85 percent are also Sunni Mus-

lims governed by the Hanafi school of Islamic law. Most

of the remaining 15 percent are Hindus.

Islam in Bengal dates from the arrival of Turkic in-

vaders in 1200 cE. In 1576 the region was incorporated

into the Mughal Empire, which retained hegemony un-

til 1757 and the onset of the British empire in India.

Military and political domination do not by themselves

produce mass conversion; thus one mystery of South

Asian history is how the territory today comprising Ban-

sladesh came to contain some 4o percent of the Muslims

counted in British India at its first census (1872), and to

become home to around 30 percent of all South Asian

Muslims today.

In explanation of this phenomenon, the British

scholar-administrators who devised and interpreted the

early censuses, notably H. H. Risley, concluded that

massive conversion had occurred among low-caste Hin-

dus seeking refuge from caste oppression in the egalitar-

ian fold of Islam, Seen as an insult to Islam, this conclu-

sion was vigorously opposed by English-educated

‘Muslim intellectuals such as Khondkar Fazli Rubee,

whose Origins of the Musalmans of Bengal (Calcutta,

1895) attempted to show that the Muslim population of

Bengal was mainly descended from Arab, Mughal (Tur-

188 BANGLADESH

kkic), and Afghan invaders. Muhammed Abdur Rahim

(1963, 1967) has more recently sought to reiterate the

argument, but with statistical evidence that few other

historians accept. A contrasting view has it that Bengal

was the last bastion in India of a corrupt and effete Bud-

dhism, and so its people were ripe for the appeal of $f

mystics who followed the first Muslim rulers.

In one way or another, historians universally empha-

size the role of Sufism in the initial stages of Bengali

conversion to Islam. Current explorations of Bengali

Muslim history link the earliest phase of islamization to

the deforestation of the Bengal Delta by land-hungry

peasants of no discernibly stable religious commitment,

spurred on by the revenue-famished rulers of both pre-

Mughal and Mughal Bengal. In Richard Eaton’s (1993)

analysis, $0 adepts also figure prominently as charis-

matic pioneer leaders or ghdsi-pirs (“warrior saints”)

who organized the spread of farming, protected cultiva-

tors from the natural and supernatural hazards of the

forest, and spearheaded development of rural communi-

ties, linking them to the Muslim rulers. Over time, de-

votional cults initiated by these $aff pioneers came to

focus on them as “saints,” and their religious ideology,

Islam, thus embryonically embedded itself in the deltaic

countryside. This amalgam of agriculture and religion

‘ight be seen as the first stage of islamization in Bengal.

Is legacy lives on in the myth of creation found today

among Bengali Muslim cultivators, who, as described

by John Thorp (1978), see themselves as descendants of

a primordial Adam, the first Prophet of Islam and also

the First Farmer, created by God for the express pur-

pose of mastering the earth.

‘A second stage of islamization in eastern Bengal may

be witnessed in the development of a tradition syncretiz-

ing popular forms of Islam and Hinduism. Asim Roy

(1983) argues that the formal doctrines of Islam were at

first absorbed only lightly by the largely rural Bengali

population. Their folk religious culture mingled beliefs

in the fantastic with perceptions of the natural world,

and mixed superstition, myth, and magic with faith.

This was no less true of Bengali Hinduism, since it was

Vaishnavism (Krishna-focused worship) and not ortho-

dox Brahminical codes that captured the imagination of

rural people who identified themselves as Hindus, pro-

viding forms of religious devotion as emotionally satis-

fying and evocatively mystical as the Safi pirism that

had enthralled converts to the Muslim fold.

‘The result was a syneretic folk religion in which $0

pirs and Vaishnavite saints were worshiped interchange-

ably by both Hindus and Muslims. Worship itself com-

monly took form (and to this day often occurs) in di-

dactic narrative exposition by local or itinerant

charismatics, or it featured folk music whose devotional

lyrics were imbued with spiritual metaphor and allegory

intelligible to Hindus and Muslims at once, and whose

performers might claim to be either or both. Indigenous

healers and shamans might proffer curatives whose

power was derived from Qur’n and Krishna alike.

‘There was, however, a considerable gap between the

popular religion of most rural Muslims—descendants of

indigenous converts known as the ajlaf or ajraf (“low

ranked”) social classes—and Muslim lites or ashraf

noble”) classes who claimed Middle Eastern descent

and espoused a version of Islam that looked to North

India, Persia, and Arabia for its inspiration and its lin-

guistic expression (in Persian and Urdu, not in Bengali).

That gap was bridged by religious guides, preceptors,

philosophers, and poets whose writings introduced or-

thodox Islamic dogma by seeking its broad parallels in

Hinduism. For example, accounts of the life of the

Prophet might be couched in terms accommodating to

the Hindu belief in divine incarnations, and descriptions

of Fatimah might evoke the Mother Goddess of popular

Hinduism. There developed a “Muslim-Vaishnavite”

synthesis in Iyric poetry; similar efforts at harmonizing

Hindu and Muslim cosmological, mystical, and esoteric

traditions arose. Thus was constructed a syncretic ver-

sion of Islam that aimed at accommodating elite, Perso-

Arabic versions as well as the devotional, pir-focused

folk traditions of rural non-elites who had identified

themselves with the Islamic faith. This may be seen as

the second stage in the islamization of eastern Bengal.

A third stage may be posited with the rise of several

strains of revivalism confronting the homegrown, syn-

cretic Bengali variety of Islam in the early nineteenth

century. Among the most important was the Fari’

(Fard’idi) movement (from Arabic fard, recalling the

obligatory duties of Islam), founded in 1818 by Hajii

Shari‘atullah (1781-1840), an East Bengali whose

twenty years in the Arabian Muslim heartland had im-

bued him with Meccan standards of belief and practice.

Spreading rapidly throughout eastern Bengal down to

1900, this movement called upon the local Muslim faith-

ful to abandon pirism and eschew Hindu-tainted cus-

toms and beliefs. The Fariizis presented what they

considered orthodox models of Islamic credo and con-

duct and insisted that belief and behavior be shaped in

conformity with the Five Pillars. They also became ac-

tive in agrarian struggles, which often pitted Muslim

peasants against Hindu and European landlords, thus

adding a religiously communal element to the social and

political antagonisms spreading in the Bengali country-

side at this time,

Another movement, the Tariqah-i Mubammadiyah,

an Indian counterpart to the Wahhabt movement of

eighteenth-century Arabia, had been initiated in Delhi

in 1818 by Sayyid Ahmad Shahid (1786-1831). Intro-

duced into western Bengal by Titu Mir (1782-1831) in

1827, it also became involved in peasant struggles. A

key feature of this movement was its emphasis on strict

adherence to the shari‘ah; one of its offshoots, the Abl-i

Hadith (“people of hadith”) movement, was vehement

in stressing ijikad, The Ahl-i Hadith movement is the

most visible remnant of the last century’s reformist

movements in Bangladesh today, with a reported two

thousand local branches and two million adherents in

the mid-1980s, especially in the northern districts of the

country. Its local groups display distinctive variations in

ritual performance but otherwise avoid exclusive, sect-

like behavior and are open to relationships with Mus-

Jims of other persuasions. The Ahli Hadith is led by

highly educated and articulate spokespersons, such as

its long-standing amir, Professor Muhammad ‘Abdul

Biri, a respected Islamic scholar and top university ad-

ministrator; these leaders have developed the original

movement's doctrines toward progressive social reform

along Islamic lines.

The revivalist “purification” of Bengali Islam under-

mined its earlier syncretism by stressing the differences

between Islam and Hinduism. As Rafiuddin Ahmed

(1981) has argued, these militant movements deepened

Islamic consciousness in late nineteenth-century East

Bengal and paved the way for effective mobilization of

its Muslim peasantry by the Muslim elites who would

lead the Pakistan movement in the twentieth century.

Such elites included in their number many belonging to

an Islamic modernist tradition, begun in the late nine-

teenth century and similar to its counterparts elsewhere

in the Muslim world, which advocated Western educa-

tion and stressed the utility of European science in har-

monic combination with classical Islamic scientific and

humanistic learning and moral ideals. Thus, in its Is-

lamic dimension, by 1947 the maturing national identity

of East Bengal not only retained remnants of Sufism and

syncretism but also contained elements of orthodox fun-

damentalism and modernism.

From a large survey she has recently conducted of

BANGLADESH 189

Bangladeshi Muslims claiming an active faith, Razia

Akter Banu (1992) has identified three basic tendencies

in present-day Bangladeshi Islam, all of which have

their roots in these historic movements. Nearly half of

her rural and a quarter of her urban respondents

evinced the syncretism of folk belief and practice de-

scribed above. Followers of popular forms of Islam most

often represent lower levels of income, education, and

‘occupation.

Attribution of supernatural power to pirs is an espe~

cially salient feature of popular Bangladeshi Islam.

Commemorative gatherings (‘urs) at the ubiquitous

tombs (mazar) of the pirs occur year-round, and major

shrines are located throughout the country. At least one

‘major $afi order (tarigah), the Qadiriyah, has a large

following, with a national center in the Chittagong dis-

trict village of Maijbhandar. These Maijbhandari, as

they are called, meet in weekly gatherings (mahfil)

where religious folk music forms the centerpiece of de-

votional worship, and they have an annual conclave at

their national center. The nature and extent of $afi ac-

tivity in Bangladesh needs much further study, but it is

widespread and attracts persons of all social, educa-

tional, and occupational backgrounds.

Another 5o percent of Banu’s rural sample, and more

than 60 percent of her urban respondents, claimed ad-

herence to orthodox forms of Islam: literality in accep-

tance of Qur’én and hadith, strictness in observing the

obligatory duties, and total obedience to the Hanafi

school of law. Both urban and rural people of moderate

‘educational background register among the ranks of the

‘orthodox; in the rural areas orthodoxy is associated with

relatively higher levels of land ownership, in contrast

to its correspondence with middle levels of income in

the cities.

Finally, while very few rural Bangladeshi Muslims es-

pouse an Islamic modernist point of view, with its em-

phasis on rationalism and scientism and rejection of lit-

ceralistic determinism, Banu found that 12 percent of the

urbanites in her sample adopted this perspective. Not

surprisingly, espousal, of this viewpoint was associated

with high levels of Western education as well as with

higher occupation and income.

Banu’s study also suggests that adherents to both the

Popular and orthodox versions of Islam hover between.

high and moderate levels of actual practice, as measured

by the degree to which they claim to carry out the daily

and annual obligatory duties of the faithful. Modernists

tend toward moderate and lower levels of practice, as

190 BANGLADESH

one might surmise. In my observation, the daily and

weekly requirements of prayer and the mandate of the

annual fast are widely met by rural Bangladeshis, and a

good deal of social pressure is exerted via shaming

mechanisms and fear of embarrassment toward the

maintenance of Muslim propriety in public conduct. In

urban areas, where normative conformity is more diffi-

cult to exact, performance in these areas is more varied.

The Islamic component of East Bengal’s regional

identity was at the forefront of its people's political con-

sciousness during their struggle for an independent Pa-

kistan until 1947. Thereafter, however, the Bengalis in

‘what became East Pakistan became disillusioned as they

perceived their economic, political, and cultural inter-

ests increasingly subordinated to those of their confiréres

in non-Bengali West Pakistan. Accordingly, the ethno-

linguistic element of their national identity, especially

Pride in their language and its associated cultural tr

tions, took political primacy, and although their reli-

gious commitment to Islam by no means waivered, it no

longer shaped their immediate political goals. By the

‘mid-1950s Bengali enthusiasm for the Muslim League,

which had spearheaded Pakistani independence, became

deeply eroded. The growing rift between Pakistan’s

eastern and western wings broke into rebellion in 1971,

and, led by the secular nationalist Awami League, an

independent Bangladesh was born. [See also Muslim

League; Awami League.]

In part because members of Islamic political parties

had—sometimes violently—opposed separation from Pa-

kistan, the first constitution of Bangladesh (1972) pro-

claimed secularism as a principle of state policy and pro-

hibited political parties based on religious affiliation.

Individuals thought to have stood against independence

on religious or other grounds were stigmatized, and, not

uncommonly, ordinary Muslims visibly observant in

dress and ritual performance could find themselves

shunned or mocked by supporters of the party in power.

A great many Bangladeshi Muslims, however, were

uncomfortable with official secularism. Daily religious

practice went on unabated, as did the expressions of

popular and orthodox Islam noted above. The Delhi-

based Tablighi Jama‘at, which aims at strengthening Is-

lamic faith and practice among believers, became highly

active in the country, attracting large numbers and pre-

saging an Islamic resurgence. In 1975 the increasingly

dictatorial Awami League was overthrown; a more fa-

vorable domestic climate for the political expression of

Islam was ushered in.

Against this domestic background, one should also

note that Bangladesh was receiving mounting propor-

tions of its foreign aid from the oil-rich and conservative

Arab states, where Bangladeshis were working in mas-

sive numbers, especially in Saudi Arabia. The post-coup

government of Ziaur Rahman (1975-1981) became

prominently active in Islamic international organiza-

tions, and increasing ties to the wider Muslim world

‘may have prompted it in 1977 to replace the secularism

clause of the constitution with a proclamation of “abso-

Jute faith and trust in almighty Allah,” mandating that

government strengthen “fraternal ties with the Muslim

states on the basis of Islamic solidarity.” The Zia gov-

‘ernment began to sponsor Islam as well, in its establish-

ment of a cabinet-level Division of Religious Affairs,

creation of an Islamic Foundation for research, and

plans for a new Islamic University. Under a separate

directorate in the Ministry of Education, since 1975 the

number of madrasahs in Bangladesh has increased by 50

percent, their teachers by one-third, and students by

well over two-thirds. The subsequent government of H.

‘M, Ershad (1982-1991) continued in this vein; the pres-

ident and members of his cabinet publicly associated

themselves with a famous and politically active pir. In

1988 the National Assembly passed a constitutional

amendment declaring Islam the “state religion” of the

country.

The intent and import of this change remain unclear.

Ie did not, however, result in institution of the shari‘ah.

Bangladeshis have not recently been prone toward fund-

amentalist government. In the first post-independence

National Assembly election (1979) that permitted Islam-

‘oriented parties to compete, the conservative but non-

theocratic Muslim League won 19 of 300 seats and 10

percent of the popular vote; no fundamentalist parties

contested. But in the parliamentary election of 1986, the

Muslim League's mere four seats were surpassed by ten

that went to the Jama‘at-i Islimi (Islamic Assembly),

which advocates a fullfledged Islamic state. Harbinger

of things to come, the Jama‘at’s student front, the

Islamiya Chhatra Shibir (Islamic Student Group),

emerged as a major force in Bangladesh's politically vol-

atile universities. Not surprisingly, then, the Jamé‘at

garnered nearly 12 percent of the popular vote in the

1991 National Assembly elections, winning 18 (6 per-

cent) of all 300 seats, and 8 percent of the 221 it con-

tested.

It remains to be seen whether Bangladesh will ever

become an Islamic state. Its past has shown, however,

that Islam seeks perennial renewal in the dynamic inter-

play between Bengali nationalism and Muslim universal-

ism that lies at the heart of its national identity.

{See also Islam, article on Islam in South Asia; Pir.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abmad Khan, Muin-ud-din. History ofthe Fara'idi Movement in Ber-

gal, 1818-1906. Karachi, 1965. Definitve work t0 date on the

‘Faris and their relations with other movements; essential read-

ing on Islamic revivalism in nineteenth-century Bengal.

Ahmed, Rafiuddin. The Bengal Mustims, 1871-1906: A Ques for Iden-

ti. Delhi, Oxford, and New York, 1981. Best general study of

nineteenth-century Bengali Muslim society, covering religious, s0-

cial, and politcal development in an integrated manner. See also

his Islam in Bangladesh: Soci, Culte, ond Politics (Dhaka,

1983), and Religion, National, and Politics in Bangladesh (New

Dethi, 1990), both collections of orginal esays on social and politi

cal aspects of Islam in Bangladesh since 1971

Ahmed, Sula. Muslim Community in Bengal, 1884-1912. Dhaka,

1974. Comprehensive study with chapters on educational, social,

economic, and political development, focusing on elites.

Banu, U. A. B. Razia Akter. Islam in Bangladesh. Leiden and New

York, 1992. Unique and highly imaginative social science survey

esearch study of current atitudes and beliefs, with informative

historical background chapters.

Eaton, Richard Maxwell. The Rite of Islam ond the Bengal Frontier,

1204-1760. Berkeley, 1993. Path-breaking reassessment of the

spread of Islam as seen in the context of Bengali agrarian and eco-

omic history.

Hag, Muhammed Enamul. A History of Sufciom in Bengal. Dhaka,

1975. Detailed, if not particularly critical, history through the me-

dieval period, with an outline of major beliefs and biographical

Karim, Abdul. Social History of the Musims in Bengal, Doun t A.D.

1538. Dhaka, 1959. Covers intellectual development, social organi

zation, and daily life in the eatly Islamic period

Mallick, Azizur R. British Policy and the Musims of Bengal, 1757-

1856. Dhaka, 1961. Focus on educational policy and its impact on

Muslim society; background on religious syncretism and revivalist,

Rahim, Muhammed Abdur. Social and Cultural Histry of Bengal. 2

vols. Karachi, 1963-1967. Tour de force survey of Bengal’s medieval

history from a Muslim nationalist perspective; covers all aspects,

including both Hindu and Muslim societies,

Raychaudhuri, Tapan, Bengal under Akbar and Jahangir: An Inroduc-

tory Study in Social History. Delhi 1953. Seminal study ofthe early

‘Mughal period, with important chapters on religious development

Roy, Asim. The Islamic Syncreistic Tradition in Bengal. Princeton,

1983, The best study of beliefs and practices in the prerevivalist

medieval period; essential for the study of popular Islam in Bangla-

desh today.

‘Thorp, John P., Jr. “Masters of Earth: Conceptions of ‘Power’ among

‘Muslims of Rural Bangladesh.” Ph.D. dis., University of Chicago,

1978. Pioneering anthropological study of community organization

and religious culture among Bangladeshi Muslim peasantry.

Perer J. Bextocet

BANKS AND BANKING 191

BANKS AND BANKING. Modern banking was

first established in the Islamic world in the mid-nine-

teenth century. Financial intermediaries of course were

‘not new to the region, as the sophisticated Moslem trad-

ing economies had long used specie as a means of ex-

change, and money changers and moneylenders carried

out their business in most urban centers. Money chang-

cers were especially active in the cities of the Hejaz, such

as Mecca and Medina, catering for needs of the Pi

agrims, demonstrating that there was no Islamic objec

tion to currency dealings and the exchange of precious

metals. The prohibition of ribé (“interest”) in the

Qur'an, however, meant that there was much suspicion

of conventional commercial banking in the form in

which it had developed in Europe.

The Penetration of Colonial Banking. The early

commercial banks were all European owned, the Impe-

rial Ottoman Bank being an Anglo-French venture, and

the Imperial Bank of Persia was British owned and man-

aged. Much financial intermediation in the Ottoman ter-

ritories was in the hands of Greek Christians or Jews

rather than Muslims. The latter were keen traders, and.

indeed the prophet Muhammad had been a trader, but

there was a reluctance on religious grounds to get in-

volved in the collection and lending of money. Muslim

traders granted credit in kind on a deferred-payment bi

sis rather than charging interest. Advances were covered

from personal and family equity rather than from sav-

ings attracted from strangers by the promise of interest.

‘The Imperial Banks served the government and the

trade of the European empires rather than the local

Muslim business community or the wealthy landlord

class. The management of Ottoman debt was a major

undertaking, and the Imperial Ottoman Bank acted on

behalf of the sultan in arranging bond issues in London

and Paris. The Imperial Bank of Persia was closely in-

volved with the Anglo-Iranian oil company, later to be-

come British Petroleum. The National Bank of Egypt,

a wholly British-owned institution, was mainly involved

in the finance of cotton exports, on which the Lanca-

shire textile industry depended. This trade was con-

tolled by Greek and Levantine merchants rather than

Egyptian Muslims. In Malaya the Hong Kong and

Shanghai Bank was active in the finance of the rubber

trade, but even the plantation workers were immigrants

rather than indigenous Muslims.

‘Muslim-owned Commercial Banks. It was not until

the 1920s that groups of Muslim businessmen began to

realize that traditional financial intermediation was of

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Historical Foundations of The Law of EvidenceDocument35 pagesHistorical Foundations of The Law of EvidenceJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Seerat BooksDocument2 pagesSeerat BooksJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Run To ParadiseDocument1 pageRun To ParadiseJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Poro POD PDFDocument184 pagesPoro POD PDFmashihoorNo ratings yet

- Mvnvwei PV L 'Ywbqv: Gvkzvevzzj EvqvbDocument7 pagesMvnvwei PV L 'Ywbqv: Gvkzvevzzj EvqvbJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Manarat International University: Exam: Spring 2017-Mid-Term Session: Spring 2017Document1 pageManarat International University: Exam: Spring 2017-Mid-Term Session: Spring 2017Jiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Anglo Muhammadan LawDocument13 pagesAnglo Muhammadan LawJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- History BooksDocument4 pagesHistory BooksJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Rasuler Chokhe Duniya AbridgedDocument11 pagesRasuler Chokhe Duniya AbridgedJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Dhaka - BG Prayer TimesDocument2 pagesDhaka - BG Prayer TimesSheikh RionNo ratings yet

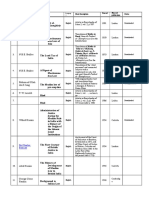

- Theodoor Willem Juynboll Thomas Patrick Hughes: Sl. No Author Title Short Description Year of Place of Publication StatusDocument1 pageTheodoor Willem Juynboll Thomas Patrick Hughes: Sl. No Author Title Short Description Year of Place of Publication StatusJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Asus P 2430 U 1 TB 4 GB DDR 4 Core I 3 6 Gen 14Document1 pageAsus P 2430 U 1 TB 4 GB DDR 4 Core I 3 6 Gen 14Jiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet

- Al Ahkamus SultaniyyahDocument1 pageAl Ahkamus SultaniyyahJiaor Rahman MunshiNo ratings yet