Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2020 Report The Economic Impact of The Arts Economy Is On The Rise

Uploaded by

alvaro asperaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2020 Report The Economic Impact of The Arts Economy Is On The Rise

Uploaded by

alvaro asperaCopyright:

Available Formats

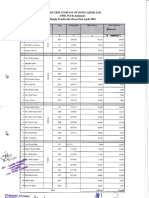

Office of Research & Analysis

March 2020

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report

The Economic Impact of the Arts Economy Is on the Rise

In 2017, the produc on of arts and cultural goods The arts con nue to contribute more to the U.S.

and services in the United States contributed economy than do construc on, transporta on

$877.8 billion, or 4.5 percent, directly to the and warehousing (combined), and agriculture

na on’s GDP. There were over 5 million wage‐ (among other sectors. The arts also generate a

and‐salary workers employed in the arts and widening trade surplus. From 2006 to 2017, this

cultural sector. Compensa on for these workers surplus grew 9‐fold, to more than $25 billion.

totaled $405 billion in 2017.

Below are summary findings on the arts economy. Arts and Cultural Contribu ons to the Crea ve

Click on the topic to go directly to that sec on of Economy

the document. Exports of Arts and Cultural Goods and Services

Total Value of the U.S. Arts Economy The Nonprofit Arts Economy

Trends in Arts and Cultural Produc on

Workers Engaged in Arts and Cultural Produc on

Consumer Spending on Admissions to Performing

Arts Events

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report was produced by the Na onal

Endowment for the Arts in March 2020 using data from the Arts and Cultural Produc on Satellite Account

(ACPSA), produced in partnership with the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. More informa on is available

at www.arts.gov.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 1

I. Total Value of the U.S. Arts Economy 2. Arts and culture surpasses a number of other

sectors such as construc on, transporta on

1. In 2017, arts and cultural produc on

and warehousing, and agriculture (including,

contributed $877.8 billion to the U.S.

forestry, fishing, and hun ng).i

economy.

The value added by arts and culture to the

That produc on amounted to 4.5 percent

U.S. economy is 5 mes greater than the

of U.S. GDP.

value added by the agricultural sector.

Arts and culture adds $87 billion more than

construc on and $265 billion more than

transporta on and warehousing to the U.S.

economy.

Arts and culture

Arts and culture

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 2

3. Six detailed industries emerge as top

contributors to the total economic value

added by arts and culture:

Broadcas ng (excluding sports; web

publishing and streaming services;

publishing (excluding internet publishing);

mo on picture industries; performing arts

companies and independent ar sts,

writers, and performers; and arts‐related

retail trade.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 3

II. Trends in Arts and Cultural Produc on Over the most recent 3‐year period (2015‐

2017), the average annual growth rate of the

1. For nearly two decades, the total economic

value added by arts and culture (adjusted for

value added by arts produc on has generally

infla on) was 4.45 percent, more than double

risen.

the growth rate of the total U.S. economy (+ 2

percent).

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 4

2. The fastest‐growing industries producing arts The value added by sound recording grew by

and cultural goods and services include web 5.8 percent over the same three‐year

publishing and streaming, sound recording, and period.

performing arts presenters. The value added by performing arts

The total value added to the U.S. economy presenters grew at nearly the same clip—5.5

by web publishing and streaming grew by an percent.

average annual rate of 29.2 percent from

2015 to 2017.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 5

III. Workers Engaged in Arts and Cultural 2. The number of workers employed to produce

Produc on arts and cultural goods and services has risen in

recent years.

1. In 2017, the arts and cultural sector employed

more than 5 million wage‐and‐salary workers. Between 2010 and 2017, the years following

the Great Recession, the arts and cultural

Compensa on for those workers topped

economy added 392,000 workers.

$400 billion that year.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 6

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 7

IV. Consumer Spending on Admissions to 2. Between 2000 and 2017, consumer spending

Performing Arts Events on admissions to the performing arts, as a

share of all U.S. consumer spending, rose from

1. In 2017, consumers spent $26.5 billion on

0.13 percent to nearly 0.20 percent.

admissions to performing arts events.

Personal consump on spending on admissions to performing arts events: 2017

(in millions)

Performing arts $26,460

Theater/musical theater/opera $17,004

Music groups and ar sts1 $3,669

Other performing arts2 $3,030

Symphony orchestras and chamber

groups $2,033

Dance $724

1

Includes jazz, rock, and country music performances.

2

Examples include carnivals, circuses, ice‐ska ng performances, and magic shows

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 8

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 9

V. Arts and Cultural Contribu ons to the Crea ve 2. Between 2015 and 2017, average annual

Economy growth in produc on of copyright‐intensive

arts and cultural goods and services grew 6.3

1. Arts and cultural produc on accounts for half

percent.

of the U.S. “crea ve economy.”

Average annual growth in produc on was

In 2017, copyright‐intensive industries con‐

par cularly strong for web publishing and

tributed $1.1 trillion to the U.S. economy. Of

streaming; sound recording; and publishing,

that value, $569 billion stemmed from the

including arts‐related so ware publishing.

produc on of arts and cultural goods and

services.

Value added by copyright‐intensive industries: 2017

(millions)

Total value Value added from arts

added and cultural produc on

All copyright‐intensive industries $1,101,742 $569,015

Broadcas ng1 $279,903 $143,441

2

Web publishing and streaming $140,683 $125,579

Publishing $262,974 $95,681

Mo on picture industries $77,186 $74,060

Performing arts companies and in‐

dependent ar sts, writers, and en‐

tertainers $53,095 $52,212

Adver sing $75,898 $30,056

Specialized design $23,132 $21,468

Sound recording $14,222 $14,129

Photographic services $8,617 $8,444

Computer systems design3 $166,032 $3,945

1

Excludes sports.

2

See the endnotes to this summary report for more informa on about the industry labeled "web publishing and streaming."

3

Refers to computer systems design suppor ng sound recording and mo on picture produc on.

Data source: Arts and Cultural Produc on Satellite Account (ACPSA),

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and Na onal Endowment for the Arts

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 10

Average annual growth rates of real value added by arts and culture: 2015‐2017

Copyright‐intensive industries only

All copyright‐intensive industries 6.3%

1

Web publishing and streaming 29.2%

2

Computer systems design 12.0%

Sound recording 5.8%

Publishing 5.3%

Adver sing 1.6%

Mo on picture industries 0.2%

Performing arts companies and inde‐

pendent ar sts, writers, and enter‐

tainers ‐0.1%

3

Broadcas ng ‐0.4%

Photographic services ‐0.8%

Specialized design ‐3.4%

1

See the endnotes to this summary report for more informa on about the industry labeled "web publishing and streaming."

2

Refers to computer systems design suppor ng sound recording and mo on picture produc on.

3

Excludes sports.

Data source: Arts and Cultural Produc on Satellite Account (ACPSA),

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and Na onal Endowment for the Arts

Arts and Cultural Produc on as Investment

Historically, private fixed assets were in the form of physical capital (i.e., plant and equipment assets). In

more recent years, however, the BEA has expanded its defini on of investment to include the capitaliza on

of intangible assets.

For example, so ware development was first counted as fixed private investment in 1999. And in 2013, the

na onal income and product accounts (NIPAs) were revised to include research and development expendi‐

tures as investment.

Also in 2013 was the BEA revision that capitalized “entertainment originals.” Entertainment originals refer

to theatrical movies; long‐lived television programs; books; music; and other “miscellaneous entertain‐

ment” such as scripts and scores for the performing arts, gree ng card designs, and stock photography.

In 2015, for example, investment in entertainment originals was $77.3 billion. In 2017, that investment rose

to $84 billion.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 11

VI. Exports of Arts and Cultural Goods and 2. Arts and cultural exports are driven by movies

Services and TV programs, adver sing, arts‐related

so ware, and jewelry and silverware.

1. The U.S. exports more arts and cultural goods

and services than it imports, resul ng in a trade In 2017, those commodi es accounted for

surplus. $49 billion, or two‐thirds of all U.S. arts

exports.

In 2017, the U.S. exported nearly $30 billion

more in arts and cultural goods and services

than it imported.

The arts and cultural trade surplus has

increased since 2006, when it was $3.3

billion.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 12

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 13

VII. The Nonprofit Arts Economy The total value added to the U.S. economy

by tax‐exempt mo on picture and sound

recording industries was $700 million.

1. In 2017, nonprofit performing arts companies,

performing arts presenters, and museums (and

similar ins tu ons) contributed approximately

$15 billion to the U.S. economy and employed

more than 200,000 workers.

Nonprofit Book Publishers

County Business Pa erns (CBP) data, which are produced by the U.S. Census Bureau, furnish sta s cs on

business establishments by legal form of organiza on and by employment size.

In 2017, the CBP tallied 2,440 book publishers. More than 40 percent of those were “S” corpora ons, which

refers to corpora ons in which profits/losses are channeled to the owners, who also pay the taxes. Nearly

800 were “C” corpora ons, meaning that the corpora on is a separate en ty from the owners.

That year, there were also 200 nonprofit book publishers. They employed just under 6,000 workers and paid

more than $300 million in compensa on.

About half of the nonprofit book publishers employed fewer than five employees. Another 47 establish‐

ments employed between 5 and 19 employees, while 35 staffed 20‐99 workers. In 2017, 15 nonprofit book

publishers employed 100 or more employees.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 14

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 15

Endnotes

I

The sectors given are not mutually exclusive. For example, arts and cultural produc on includes parts of the

construc on sector—namely, the building of arts and cultural facili es; travel and tourism includes related

performing arts spending.

Ii

In this report, “other informa on services” is labeled “web publishing and streaming.” The category also includes

non‐government libraries and archives and other services such as stock photo agencies.

Iii

“Real” es mates are measured in 2012 chained dollars.

Iv

The Arts Endowment’s Office of Research & Analysis defines the “crea ve economy” as value added by industries

that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has iden fied as copyright‐intensive. See “Intellectual Property and the

U.S. Economy: 2016 Update,” Economics & Sta s cs Administra on and U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

V

Es mates by tax status were derived by combining data from the Arts and Cultural Produc on Satellite Account

(ACPSA) and the Economic Census, which is produced by the U.S. Census Bureau. The analysis also used data from

the Census Bureau’s Nonemployer Sta s cs (NES) program, which captures the earnings of self‐employed workers.

Value added by nonprofit performing arts presenters ($3 billion), for example, was derived by mul plying the total

ACPSA value added for the industry ($15.3 billion) by 20 percent, which is the share of revenue earned by tax‐

exempt promoters of performing arts, sports, and similar events, according to the 2017 Economic Census.

This method, however, may understate nonprofit value added by performing arts presenters. It is likely that the 20

percent es mate would be higher if the Economic Census data for promoters excluded sports and other non‐arts

events. In other words, if the Economic Census data were restricted to performing arts presenters, the share of

revenue tallied as tax‐exempt may have been greater than 20 percent.

A similar argument applies to employment in tax‐exempt performing arts establishments—it may have been higher

than the 29,000 workers shown in this report for 2017.

The U.S. Arts Economy (1998‐2017): A Na onal Summary Report 16

You might also like

- MARODIN, Helen B. K. - Unlocking Piranesi's Imaginary PrisonsDocument167 pagesMARODIN, Helen B. K. - Unlocking Piranesi's Imaginary Prisonsalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Rumi's Thought On Whitman's PoetryDocument10 pagesThe Influence of Rumi's Thought On Whitman's Poetryalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- BREWSTER, Sir David - Letters On Natural Magic (1856)Document180 pagesBREWSTER, Sir David - Letters On Natural Magic (1856)alvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- 6 - BUZPINAR, Ş. Tufan - A - Reassessment - of - Anti - Ottoman - PalacardsDocument37 pages6 - BUZPINAR, Ş. Tufan - A - Reassessment - of - Anti - Ottoman - Palacardsalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- Alterity in American Literature The Faces of The Other in Melville's Moby-Dick and Billy BuddDocument10 pagesAlterity in American Literature The Faces of The Other in Melville's Moby-Dick and Billy Buddalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- Empire of Ecstasy Nudityand Movementin G PDFDocument6 pagesEmpire of Ecstasy Nudityand Movementin G PDFalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- 3 - ÇETINSAYA, Gökhan - Sultan Abdülhamid II's Domestic PolicyDocument36 pages3 - ÇETINSAYA, Gökhan - Sultan Abdülhamid II's Domestic Policyalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- Byron - Fragment of A Novel (1816)Document4 pagesByron - Fragment of A Novel (1816)alvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- Hillel Ofek - Why The Arabic World Turned Away From Science - The New AtlantisDocument29 pagesHillel Ofek - Why The Arabic World Turned Away From Science - The New Atlantisalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- LOW, Michael Christopher - The Mechanics of MeccaDocument380 pagesLOW, Michael Christopher - The Mechanics of Meccaalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- STAGG, John - "The Vampyre" (1810)Document4 pagesSTAGG, John - "The Vampyre" (1810)alvaro aspera100% (1)

- BAUDELAIRE, Charles - Metamorphoses of The Vampire (1857)Document1 pageBAUDELAIRE, Charles - Metamorphoses of The Vampire (1857)alvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- GOETHE - Bride of Corinth (1797) PDFDocument4 pagesGOETHE - Bride of Corinth (1797) PDFalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- BYRON - The Giaour (1813) (Vampiric Extract)Document2 pagesBYRON - The Giaour (1813) (Vampiric Extract)alvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- OSSENFELDER, Heinrich August - Der Vampir (1748) PDFDocument1 pageOSSENFELDER, Heinrich August - Der Vampir (1748) PDFalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- KIPLING, Rudyard - The Vampire (1897)Document1 pageKIPLING, Rudyard - The Vampire (1897)alvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- GABRIEL, Douglas - Scythianos - The Hidden MasterDocument89 pagesGABRIEL, Douglas - Scythianos - The Hidden Masteralvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- YEATS, William Butler - Oil and Blood (1889) PDFDocument1 pageYEATS, William Butler - Oil and Blood (1889) PDFalvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- The Raven and Other Poems - The Raven - Wiki SourceDocument4 pagesThe Raven and Other Poems - The Raven - Wiki Sourcealvaro asperaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Music Video: Performance Task (Peta)Document2 pagesMusic Video: Performance Task (Peta)Ellyza SerranoNo ratings yet

- As The Record Spins Materialising ConnecDocument25 pagesAs The Record Spins Materialising ConnecDr. Stan Wardel BA, MA, MChem, MBA, DPhil, DSc.No ratings yet

- Scot Taber - QuickStart GuideDocument15 pagesScot Taber - QuickStart GuidebroeckhoNo ratings yet

- Bài tập tiếng Anh lớp 7 (Unit 1 - 16)Document57 pagesBài tập tiếng Anh lớp 7 (Unit 1 - 16)nguyenanhmai100% (2)

- What A Friend We Have in Jesus Lyrics - Google Search 2Document1 pageWhat A Friend We Have in Jesus Lyrics - Google Search 2dab20nnan20godswill20No ratings yet

- Gema Sangkakala Choir BiographyDocument2 pagesGema Sangkakala Choir BiographyAndre Rudolfo YoshuaNo ratings yet

- Ebook Como Se Dice Student Text PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesEbook Como Se Dice Student Text PDF Full Chapter PDFnancy.larsen721100% (26)

- Grammar Reference: - Teacher Su Language CentreDocument60 pagesGrammar Reference: - Teacher Su Language CentreKhin Thandar WinNo ratings yet

- Quiz 3 EnglishDocument2 pagesQuiz 3 EnglishAmber NicoleeNo ratings yet

- 2 Bac. Addition and ConcessionDocument1 page2 Bac. Addition and ConcessionDavinchi Davinchi DaniNo ratings yet

- My English by Julia AlvarezDocument6 pagesMy English by Julia AlvarezLorena AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- Theme of MusicDocument11 pagesTheme of MusicBarathyNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 6 - Third Periodical ExamDocument9 pagesMapeh 6 - Third Periodical ExamReichelle Flores93% (14)

- Cello - Concerto - No.1 - in - C - Major - Hob - VIIb1 - Joseph - Haydn Clarinetes-Oboe - 1Document1 pageCello - Concerto - No.1 - in - C - Major - Hob - VIIb1 - Joseph - Haydn Clarinetes-Oboe - 1Samuel FabianoNo ratings yet

- Heroes Del Silencio-Entre Dos TierrasDocument13 pagesHeroes Del Silencio-Entre Dos Tierrasjesus elias martinez yah100% (1)

- Jurassic Park: Conductor's SheetDocument10 pagesJurassic Park: Conductor's SheetmartinNo ratings yet

- 1950 Epiphone Triumph RegentDocument6 pages1950 Epiphone Triumph RegentBetoguitar777No ratings yet

- ABS CBN Schedule (1987 1999)Document1 pageABS CBN Schedule (1987 1999)Lian Las Pinas100% (1)

- Kathleen DeberrybrungardDocument6 pagesKathleen DeberrybrungardCASSIO UFPINo ratings yet

- Frank SinatraDocument1 pageFrank SinatraJosue Rivera VillaNo ratings yet

- Cifra Club - Natalie Imbruglia - TornDocument3 pagesCifra Club - Natalie Imbruglia - TorncristianprNo ratings yet

- Películas en CD y DvdsDocument2 pagesPelículas en CD y DvdsAsociación Amigos de India-ColombiaNo ratings yet

- Root-Third-Seventh Chords - Antonio FlorisDocument1 pageRoot-Third-Seventh Chords - Antonio FlorisAntonio FlorisNo ratings yet

- Program Muzica Nuntapaul Si MihaDocument40 pagesProgram Muzica Nuntapaul Si MihaRamo RamoNo ratings yet

- Quarter - Third - / Week 3:: Concept Notes With Formative ActivitiesDocument15 pagesQuarter - Third - / Week 3:: Concept Notes With Formative ActivitiesRuth AramburoNo ratings yet

- Noboborsho Allowance 20Document2 pagesNoboborsho Allowance 20Haripur grid ss High voltage grid substationNo ratings yet

- Radio Interview PlanningDocument2 pagesRadio Interview PlanningCharlie ParkesNo ratings yet

- English I Cultural Programme ReviewDocument2 pagesEnglish I Cultural Programme ReviewDhananjay TuduNo ratings yet

- Lyrics - Faith Over FearDocument2 pagesLyrics - Faith Over FearZarita CarranzaNo ratings yet

- Sing Street: Directed by John CarneyDocument32 pagesSing Street: Directed by John Carneybrigid mcmanusNo ratings yet