Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review of "The Effect of Unions On The Structure of Wages: A Longitudinal Analysis"

Uploaded by

Freed Drags0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views2 pagesThis paper analyzes the effect of unions on wage structure using a longitudinal estimation technique accounting for misclassification of union status and correlations between union status and productivity. Cross-sectional estimates show a large positive union wage gap for lower-skilled workers but a negative gap for higher-skilled workers. The longitudinal estimates suggest these patterns arise from positive selection of lower-skilled union members and negative selection of higher-skilled union members. Even correcting for selection biases, the union wage effect is larger for lower-skilled workers, compressing wage differences between skill groups in the union sector.

Original Description:

Original Title

426585_LaborEcon_TugasWeek9

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis paper analyzes the effect of unions on wage structure using a longitudinal estimation technique accounting for misclassification of union status and correlations between union status and productivity. Cross-sectional estimates show a large positive union wage gap for lower-skilled workers but a negative gap for higher-skilled workers. The longitudinal estimates suggest these patterns arise from positive selection of lower-skilled union members and negative selection of higher-skilled union members. Even correcting for selection biases, the union wage effect is larger for lower-skilled workers, compressing wage differences between skill groups in the union sector.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views2 pagesReview of "The Effect of Unions On The Structure of Wages: A Longitudinal Analysis"

Uploaded by

Freed DragsThis paper analyzes the effect of unions on wage structure using a longitudinal estimation technique accounting for misclassification of union status and correlations between union status and productivity. Cross-sectional estimates show a large positive union wage gap for lower-skilled workers but a negative gap for higher-skilled workers. The longitudinal estimates suggest these patterns arise from positive selection of lower-skilled union members and negative selection of higher-skilled union members. Even correcting for selection biases, the union wage effect is larger for lower-skilled workers, compressing wage differences between skill groups in the union sector.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Frederick Emmanuel Susanto

18/426585/EK/21916

Review Of “The Effect Of Unions On The Structure Of Wages: A

Longitudinal Analysis”

This paper studies the effects of unions on the structure of wages, using an estimation

technique that explicitly accounts for misclassification errors in reported union status, and

potential correlations between union status and unobserved productivity. There is still

substantial disagreement over the extent to which differences in the structure of wages

between union and nonunion workers represent an effect of trade unions, rather than a

consequence of the nonrandom selection of unionized workers. Over the past decade several

alternative approaches have been developed to control for unobserved heterogeneity between

union and nonunion workers. This paper presents some new evidence on the union wage

effect, based on a longitudinal estimator that explicitly accounts for misclassification errors in

reported union status. The estimator uses external information on union status

misclassification rates, along with the reduced-form coefficients from a multi- variate

regression of wages on the observed sequence of union status indicators, to isolate the causal

effect of unions from any selection biases introduced by a correlation between union status

and the permanent component of unobserved wage heterogeneity.

Recognizing that unions may raise wages more or less for workers of different skill

levels, and that the selection process into unionized jobs may generate different selection

biases for workers with different levels of observed skills, the econometric model is estimated

separately for five skill groups using a large panel data set formed from the 1987 and 1988

Current Population Surveys. Simple cross-sectional estimates of the union-nonunion wage

gap are large and positive for workers with lower levels of observed skills (35 percent for

workers in the lowest quintile of the distribution of observed skills) and negative for workers

with the highest levels of observed skills (-10 percent for workers in the upper quintile of

observed skills). Estimates from a measurement-error- corrected longitudinal estimator

suggest that this pattern arises from a combina- tion of a larger union wage effect for less-

skilled workers and opposing patterns of selection bias for unionized workers from the upper

and lower tails of the observed skill distribution. Among workers with lower levels of

observable skills, union members are positively selected, leading to a positive bias in the OLS

union wage gap. Among workers with higher levels of observable skill, on the other hand,

union members are negatively selected, leading to a negative bias in the OLS union wage

gap. Perhaps surprisingly, estimates for a pooled sample indicate essentially no selection bias,

suggesting that the opposing selection biases for more- and less-skilled workers

approximately "cancel" in the overall workforce. These findings shed some new light on the

nature of the union selection process, and suggest that both employer and employee

incentives affect the nature of the unobserved differences between union and nonunion

workers.

The results of the structural estimation suggest two substantive conclusions. First,

although a simple cross-sectional estimator provides a roughly unbiased estimator of the

"true" union wage effect for a pooled sample of all workers together, the biases at either tail

of the skill distribution are significant. The biases in the upper and lower tails are in opposite

direction, with evidence of positive selection among union workers with lower observed

skills and negative selection among union workers with higher observed skills. Second, even

correcting for these selection biases, the union wage effect is bigger for workers with lower

levels of observed skill.One immediate implication of the finding that the "true" union wage

effect is larger for less-skilled workers is that wage differences between broad skill groups

tend to be compressed in the union sector. This is consistent with a long literature which finds

that wage differentials by age, education, and region are typically smaller for unionized

worker. Structural models which assume that the probability of union coverage is determined

by a "single index" of observed and unobserved characteristics may be too restrictive. Most

structural analyses of the union wage effect posit a three-equation model, consisting of an

equation for the union wage for a given individual, an equation for the nonunion wage of the

same individual, and a third equation defining a latent index that determines the relative

likelihood of holding a union. In this class of models, the conditional expectation of any

unobserved wage determinants given observed union status is a function only of the index.

Thus the selectivity biases in the union-nonunion wage gap are the same for any two groups

of workers with the same probability of holding a union job.

You might also like

- Research ProposalDocument10 pagesResearch ProposalsalmanayazNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Investing: Fourteenth Edition, Global EditionDocument47 pagesFundamentals of Investing: Fourteenth Edition, Global EditionFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- BYU Study On Union EffectsDocument56 pagesBYU Study On Union EffectsLaborUnionNews.comNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Labor Market Regulationon Employment in Low-Incomecountries: A Meta-AnalysisDocument22 pagesThe Impact of Labor Market Regulationon Employment in Low-Incomecountries: A Meta-AnalysisAxel StraminskyNo ratings yet

- Performance Pay, Sorting and Social Motivation: Tor Eriksson and Marie-Claire VillevalDocument54 pagesPerformance Pay, Sorting and Social Motivation: Tor Eriksson and Marie-Claire VillevalMohit DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- Match Quality With Unpriced AmenitiesDocument40 pagesMatch Quality With Unpriced AmenitiesSrijit SanyalNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Industry and Size Effects On Wage DispersionDocument4 pagesAn Investigation of Industry and Size Effects On Wage Dispersionshakti_ileadNo ratings yet

- The Gender Pay Gap - A Literature Review 2570Document46 pagesThe Gender Pay Gap - A Literature Review 2570Luckace100% (2)

- Does Worker Loyalty PayDocument25 pagesDoes Worker Loyalty PayOcta Tian'zNo ratings yet

- Gender Wage Gap in Online Gig Economy and Gender Differences in Job PreferencesDocument33 pagesGender Wage Gap in Online Gig Economy and Gender Differences in Job PreferencesMarcosNo ratings yet

- Pellizzari 2004Document44 pagesPellizzari 2004Valentina CroitoruNo ratings yet

- Epas12 BALORIO Theorithicalbackgroud Pa CheckDocument20 pagesEpas12 BALORIO Theorithicalbackgroud Pa CheckKen Carillas AugustoNo ratings yet

- Olivetti 2008Document35 pagesOlivetti 2008Bernie Pimentel SalinasNo ratings yet

- Art 3 FullDocument2 pagesArt 3 FullanniezabateNo ratings yet

- World Development: Sarra Ben YahmedDocument15 pagesWorld Development: Sarra Ben YahmedSubroto BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Unemployment Benefits, Unemployment Subsidies and The Dynamics of EmploymentDocument39 pagesUnemployment Benefits, Unemployment Subsidies and The Dynamics of EmploymentELIBER DIONISIO RODR�GUEZ GONZALESNo ratings yet

- Jolr 2008Document16 pagesJolr 2008Christopher CoombsNo ratings yet

- Hirsch & Mueller 2020 - Ilrr - Firm Wage Premia GermanyDocument28 pagesHirsch & Mueller 2020 - Ilrr - Firm Wage Premia GermanychallagauthamNo ratings yet

- Women'S University in AfricaDocument7 pagesWomen'S University in AfricaBianca BenNo ratings yet

- WDR2013 BP Labor Market Institutions (2016!12!11 23-51-45 UTC)Document56 pagesWDR2013 BP Labor Market Institutions (2016!12!11 23-51-45 UTC)michelmboueNo ratings yet

- Hamilton 2015 Does Entrepreneurship Pay An Empirical Analysis of The Returns To Self EmploymentDocument28 pagesHamilton 2015 Does Entrepreneurship Pay An Empirical Analysis of The Returns To Self EmploymentMarcos BalmacedaNo ratings yet

- Efficiency Wages in Pakistan's Small Scale Manufacturing Abid A. BurkiDocument26 pagesEfficiency Wages in Pakistan's Small Scale Manufacturing Abid A. BurkiHurriyah KhanNo ratings yet

- Is There A Wage Premium For Public Sector Workers?Document7 pagesIs There A Wage Premium For Public Sector Workers?aidan_gawronskiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 Reading NotesDocument1 pageLecture 6 Reading Notessc.wever.janiceNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Industrial and Labor Relations ReviewDocument15 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Industrial and Labor Relations ReviewUnJin LeeNo ratings yet

- The Compensation Penalty of Right-To-Work" Laws - Econ Policy InstituteDocument13 pagesThe Compensation Penalty of Right-To-Work" Laws - Econ Policy InstituteMiles Dylan ConwayNo ratings yet

- Quach OTDocument123 pagesQuach OTFranco CalleNo ratings yet

- Occupational Licensing and Labor Market FluidityDocument2 pagesOccupational Licensing and Labor Market FluidityCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Decomposing Wage Distributions Using Recentered Influence Function Regressors Firpo Et AlDocument60 pagesDecomposing Wage Distributions Using Recentered Influence Function Regressors Firpo Et AlDavid Van DijckeNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4324933Document53 pagesSSRN Id4324933Boris PolancoNo ratings yet

- Pupato - 2017 - Performance Pay, Trade and Inequality PDFDocument27 pagesPupato - 2017 - Performance Pay, Trade and Inequality PDFSiti Nur AqilahNo ratings yet

- Department of Economics: Working PaperDocument44 pagesDepartment of Economics: Working PaperDanudear DanielNo ratings yet

- Quan 200254Document37 pagesQuan 200254Minh ThùyNo ratings yet

- Shiney ChakrabortyDocument23 pagesShiney Chakrabortymarley joyNo ratings yet

- Performance-Enhancing Compensation Practice and Employee ProductivityDocument12 pagesPerformance-Enhancing Compensation Practice and Employee ProductivityDesyintiaNuryaSNo ratings yet

- Social Incentives in The WorkplaceDocument42 pagesSocial Incentives in The WorkplaceVictor Hernandez MartinezNo ratings yet

- Inequality at Work: The Effect of Peer Salaries On Job SatisfactionDocument45 pagesInequality at Work: The Effect of Peer Salaries On Job SatisfactionFatiima Tuz ZahraNo ratings yet

- Literature Review For Labour Turnover ResearchDocument8 pagesLiterature Review For Labour Turnover Researchjsllxhbnd100% (1)

- Do Friends and Relatives Really Help in Getting A Good JobDocument59 pagesDo Friends and Relatives Really Help in Getting A Good JobTevfik CansuNo ratings yet

- Spillover Effects From Voluntary Employer Minimum WagesDocument74 pagesSpillover Effects From Voluntary Employer Minimum WagesStuff NewsroomNo ratings yet

- Fringe Benefits and Job SatisfactionDocument22 pagesFringe Benefits and Job SatisfactionAfnan Mohammed100% (1)

- WP 1125 Ability Matching and Occupational Choice PDFDocument66 pagesWP 1125 Ability Matching and Occupational Choice PDFpluk.shellacabrezosNo ratings yet

- Spencer EmployeeVoiceEmployee 1986Document16 pagesSpencer EmployeeVoiceEmployee 1986Bishnu Bkt. MaharjanNo ratings yet

- Ab - Bas (FRANCE)Document8 pagesAb - Bas (FRANCE)Lan AnhNo ratings yet

- LACEA Paper RevisedDocument46 pagesLACEA Paper RevisedJosé Ignacio GonzálezNo ratings yet

- CompansationDocument3 pagesCompansationMohammad Shahin AlamNo ratings yet

- Pension StudyDocument10 pagesPension StudyJon OrtizNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction and PromotionsDocument35 pagesJob Satisfaction and PromotionsBryan TeeNo ratings yet

- Job Matchand Occup ChoicDocument38 pagesJob Matchand Occup Choicpluk.shellacabrezosNo ratings yet

- Academic ResearchDocument18 pagesAcademic ResearchTam NguyenNo ratings yet

- Pay StructureDocument10 pagesPay StructurePooja GaonkarNo ratings yet

- wk7 DQDocument7 pageswk7 DQharum haiNo ratings yet

- Durham Research OnlineDocument53 pagesDurham Research OnlineAlok D. TiwariNo ratings yet

- The Correlation Between Minimum Wage and Youth Unemployment Final-1Document14 pagesThe Correlation Between Minimum Wage and Youth Unemployment Final-1Dakshi KumarNo ratings yet

- Review of Literature:: (Matthew J. Grawitch, 2009)Document6 pagesReview of Literature:: (Matthew J. Grawitch, 2009)Sylve SterNo ratings yet

- Accountants Job Satisfaction A Meta AnalDocument22 pagesAccountants Job Satisfaction A Meta AnalMuna Hussien OsmanNo ratings yet

- Increasing The Cost of Informal Employment Evidence From Mexico 2Document54 pagesIncreasing The Cost of Informal Employment Evidence From Mexico 2Susana FariasNo ratings yet

- Spillover Effects From Voluntary EmployeDocument74 pagesSpillover Effects From Voluntary Employeshaun19971111No ratings yet

- Marriage Premium For Women Final Paper - VFDocument18 pagesMarriage Premium For Women Final Paper - VFPhilip AbrahamNo ratings yet

- American Economic AssociationDocument21 pagesAmerican Economic Associationlcr89No ratings yet

- Summary of Uncovered Interest Parity: The Long and The Short of ItDocument2 pagesSummary of Uncovered Interest Parity: The Long and The Short of ItFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- WInter Rangkuman1Document2 pagesWInter Rangkuman1Freed DragsNo ratings yet

- Summary of Burgernomics: A Big Mac™ Guide To Purchasing Power ParityDocument2 pagesSummary of Burgernomics: A Big Mac™ Guide To Purchasing Power ParityFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Law of One Price in Scandinavian Duty-Free StoresDocument2 pagesSummary of The Law of One Price in Scandinavian Duty-Free StoresFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Law of One Price in Scandinavian Duty-Free StoresDocument2 pagesSummary of The Law of One Price in Scandinavian Duty-Free StoresFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- Summary of Managing Volatile Capital Flows: Frederick Emmanuel Susanto 18/426585/EK/21916Document2 pagesSummary of Managing Volatile Capital Flows: Frederick Emmanuel Susanto 18/426585/EK/21916Freed DragsNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Investing: Fourteenth Edition, Global EditionDocument42 pagesFundamentals of Investing: Fourteenth Edition, Global EditionFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Investing: Fourteenth Edition, Global EditionDocument55 pagesFundamentals of Investing: Fourteenth Edition, Global EditionFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- Summary Of: The Value of Saving A Life: Evidence From The Labor MarketDocument2 pagesSummary Of: The Value of Saving A Life: Evidence From The Labor MarketFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- LaborEcon TugasWeek7Document2 pagesLaborEcon TugasWeek7Freed DragsNo ratings yet

- Summary Of: The Value of Saving A Life: Evidence From The Labor MarketDocument2 pagesSummary Of: The Value of Saving A Life: Evidence From The Labor MarketFreed DragsNo ratings yet

- LaborEcon TugasWeek7Document2 pagesLaborEcon TugasWeek7Freed DragsNo ratings yet

- 1.1 EXPOSURE (Sketching The Map of A School Showing Its Structures:) Draw Your Map Here. Name of School: Marcelino Fule Memorial CollegeDocument6 pages1.1 EXPOSURE (Sketching The Map of A School Showing Its Structures:) Draw Your Map Here. Name of School: Marcelino Fule Memorial CollegeJalenne NolledoNo ratings yet

- © 2002 by John HarricharanDocument30 pages© 2002 by John HarricharanMauriceGatto50% (2)

- Diploma ELECTRICAl 6th Sem SylDocument21 pagesDiploma ELECTRICAl 6th Sem SylAadil Ashraf KhanNo ratings yet

- Ghana: InstructionsDocument2 pagesGhana: InstructionsBright KorantengNo ratings yet

- Industry Profile Journey of Indian Stock MarketDocument16 pagesIndustry Profile Journey of Indian Stock MarketapurvwebworldNo ratings yet

- Percent Air Voids in Compacted Dense and Open Asphalt MixturesDocument4 pagesPercent Air Voids in Compacted Dense and Open Asphalt MixturesAhmad KhreisatNo ratings yet

- Peter Pan, Wendy and The Sirens: The Dichotomy of Women in The Victorian EraDocument5 pagesPeter Pan, Wendy and The Sirens: The Dichotomy of Women in The Victorian EraJustine RadojcicNo ratings yet

- Investigating Causal Relationship Between Social Capital and MicrofinanceDocument18 pagesInvestigating Causal Relationship Between Social Capital and MicrofinanceMuhammad RonyNo ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of 100 W Class AB AmplifierDocument47 pagesDesign and Implementation of 100 W Class AB AmplifierreneSantosIVNo ratings yet

- Aguilar vs. Aguilar, G.R. No. 141613, 16 Dec 2005Document4 pagesAguilar vs. Aguilar, G.R. No. 141613, 16 Dec 2005info.ronspmNo ratings yet

- No Rest For The Wicked (LotFP)Document34 pagesNo Rest For The Wicked (LotFP)Paulo Ricardo100% (1)

- On Neutrosophic Feebly Open Set in Neutrosophic Topological SpacesDocument8 pagesOn Neutrosophic Feebly Open Set in Neutrosophic Topological SpacesMia AmaliaNo ratings yet

- A Investigative Study Into The Critique by Pastor Reckart of The Mysterious Cloud of 28th. February 1963 by Bernard B. CoxDocument44 pagesA Investigative Study Into The Critique by Pastor Reckart of The Mysterious Cloud of 28th. February 1963 by Bernard B. CoxBernard CoxNo ratings yet

- Berger Internship Report PDFDocument51 pagesBerger Internship Report PDFtanyabarbieNo ratings yet

- When One Plus One Doesn't Make Two - Asad UmarDocument20 pagesWhen One Plus One Doesn't Make Two - Asad UmarSinpaoNo ratings yet

- Titration - WikipediaDocument71 pagesTitration - WikipediaBxjdduNo ratings yet

- Ok Ale Boet Al ManualDocument131 pagesOk Ale Boet Al ManualJaimeNo ratings yet

- Rule 12.1. Drawing, Summoning, and Qualifying The VenireDocument34 pagesRule 12.1. Drawing, Summoning, and Qualifying The VenireJohn S KeppyNo ratings yet

- Formula C1 Unit 6 TestDocument3 pagesFormula C1 Unit 6 TestIsabella AmigoNo ratings yet

- The Kitchen (Living Concepts) - Klaus Spechtenhauser PDFDocument155 pagesThe Kitchen (Living Concepts) - Klaus Spechtenhauser PDFsachirin100% (1)

- 4th Semester SyllabusDocument13 pages4th Semester SyllabusMugu MadhavNo ratings yet

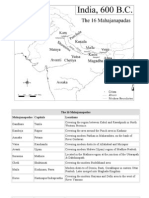

- AncientDocument12 pagesAncientVishal Bansal100% (1)

- Design of Fixed Bed Catalytic ReactorsDocument253 pagesDesign of Fixed Bed Catalytic ReactorsTissa1969100% (1)

- Palo Alto Networks Certified Network Security Administrator (PCNSA) BlueprintDocument5 pagesPalo Alto Networks Certified Network Security Administrator (PCNSA) BlueprintlokillerNo ratings yet

- Warren Larsen Chp1 (Principles of Accounting)Document147 pagesWarren Larsen Chp1 (Principles of Accounting)annie100% (1)

- LSRW Skills: A Way To Enhance CommunicationDocument4 pagesLSRW Skills: A Way To Enhance CommunicationIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 Quizzes q1w7Document2 pagesGrade 7 Quizzes q1w7api-251197253No ratings yet

- Operational Management of Ford Motors CorporationDocument56 pagesOperational Management of Ford Motors CorporationMuhammad Hassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Tenses Chart WorkDocument2 pagesTenses Chart WorkvitaNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology Project-RollNo. 236Document17 pagesResearch Methodology Project-RollNo. 236dishu kumarNo ratings yet