Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Failures in Communication Journal Article

Uploaded by

syafiqa abdullahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Failures in Communication Journal Article

Uploaded by

syafiqa abdullahCopyright:

Available Formats

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 on 7 July 2012. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.

com/ on December 8, 2021 at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Protected by

Original research

Failures in communication and

information transfer across the

surgical care pathway: interview study

Kamal Nagpal, Sonal Arora, Amit Vats, Helen W Wong, Nick Sevdalis,

Charles Vincent, Krishna Moorthy

Centre for Patient Safety and ABSTRACT and procedural complexity, with little atten-

Surgical Quality, Department Background and Objectives: Effective communication tion given to the system in which care is

of Biosurgery and Surgical is imperative to safe surgical practice. Previous studies delivered. This view has changed over the last

Technology, Imperial College

London, St Mary’s Hospital,

have typically focused upon the operating theatre. This decade with other factors such as leadership,

London, UK study aimed to explore the communication and communication and teamwork having been

information transfer failures across the entire surgical shown to contribute to safety.1 2 Of these

Correspondence to care pathway.

Sonal Arora, Department of factors, communication is perhaps the most

Methods: Using a qualitative approach, semi-structured

Biosurgery and Surgical significant, both as a skill in itself and because

Technology, Imperial College interviews were conducted with 18 members of the

effective communication is integral to the

London, 10th floor, QEQM, St multidisciplinary team (seven surgeons, five

Mary’s Hospital, South Wharf anaesthetists and six nurses) in an acute National success of all the other ‘systems’ factors.

Road, London W2 1NY, UK; Health Service trust. Participants’ views regarding Furthermore, an increased reliance upon shift

sonal.arora06@imperial.ac.uk working has placed a premium on the quality

information transfer and communication failures at

Accepted 10 April 2012 each phase of care, their causes, effects and potential of information transfer and communication

copyright.

Published Online First interventions were explored. Interviews were recorded, (ITC). Despite this, communication failures

7 July 2012 transcribed verbatim, and submitted to emergent remain a leading cause of surgical adverse

theme analysis. Sampling ceased when categorical and events.3e6 Previous studies have explored

theoretical saturation was achieved. these communication issues in surgery7e9 but

Results: Preoperatively, lack of communication their focus has primarily been on the oper-

between anaesthetists and surgeons was the most

ating theatre. Analysis of the full care

common problem (13/18 participants). Incomplete

pathway is critical as communication failures

handover from the ward to theatre (12/18) and theatre

to recovery (15/18) were other key problems. Work

are not discrete eventsdinformation loss in

environment, lack of protocols and primitive forms of one phase of care can potentially compro-

information transfer were reported as the most mise safety in a subsequent phase.10 There-

common cause of failures. Participants reported that fore, any strategy that aims to improve the

these failures led to increased morbidity and mortality. system of surgery and thus patient safety

Healthcare staff were strongly supportive of the view should involve identifying and improving

that standardisation and systematisation of ITC processes across the entire surgical

communication processes was essential to improve pathway.

patient safety. To try to address these problems, briefings,

Conclusions: This study suggests communication checklists and other techniques have been

failures occur across the entire continuum of care and

introduced. However, typically very few studies

the participants opined that it could have a potentially

have been preceded by an analysis of the

serious impact on patient safety. This data can be used

to plan interventions targeted at the entire surgical

information needs and communication

pathway so as to improve the quality of care at all vulnerabilities of the existing system ques-

stages of the patient’s journey. tioning their fitness for purpose.11 12 For

communication to be optimised, we must first

map communication failures and vulnerabil-

INTRODUCTION ities across the continuum of care. This would

allow for a full understanding of the nature

Surgical outcomes have been traditionally and scope of the problem and precise

viewed as a function of patient comorbidities targeting of interventions.

BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:843–849. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 843

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 on 7 July 2012. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on December 8, 2021 at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Protected by

Original research

This study aims to explore ITC failures across the Data analyses

entire surgical journey of patients during their hospital Transcripts were cross-checked with the original record-

stay. Specifically, we aim to look for the ITC failures, ings to ensure accuracy. The primary researcher (KN)

their causes, impact and potential interventions. analysed all interviews using emergent theme analysis.17

Each interview was then coded independently by one of

METHODS three additional members of the research team (with

backgrounds in surgery and psychology). Finally, themes

Participants across the entire set of 18 interviews were reviewed to

Eighteen healthcare professionals, including seven identify key emerging strands.17 The level of coding

surgeons, five anaesthetists and six nurses (two ward, two agreement between researchers (inter-coder reliability)

theatre and two recovery nurses) (table 1) participated was evaluated quantitatively (Pearson’s r correlation

in the study. Participants were selected using a qualitative coefficients).

sampling frame13 to ensure a broad spectrum of demo-

graphical and professional characteristics and were also Quality assurance of data analysis and interpretation

identified by snowball sampling techniques.14 Sampling The consistency (reliability) and confirmability (validity)

ceased when categorical and theoretical saturation was of data analysis and interpretation were assessed using

achieved,15 that is, when no new information was being two techniques. First, external validation of all stages of

discovered about the categories. This study sample was coding and interpretation of transcripts were performed

chosen to cover all phases of the surgical care pathway. independently by three experienced qualitative

researchers. The results were compared and there were no

Data collection significant inconsistencies. Second, member checking18

Semi-structured individual interviews were carried out by was carried out to ensure accurate interpretation of the

a researcher with a background in surgery and patient data.

safety (KN). Communication processes were examined

across three phases: preoperative, intraoperative and

RESULTS

copyright.

postoperative, initially through another methodology,

Healthcare Failure Modes and Effects Analysis.16 Six

critical phases of the surgical care pathway were identi- Coding reliability

fied. Of these, preoperative assessment and optimisa- We examined the correlations between the coders

tion, preprocedure teamwork, postoperative handover, (primary coder vs second coder) for the number of

and daily ward care phases were found to be most items that each of them identified per interview. High

vulnerable to ITC errors through hazard analysis, which correlations imply similar coding across researchers,

were the focus of the interview. therefore adequate reliability of the coding. The corre-

Surgeons’, anaesthetists’ and nurses’ views on the lations obtained were high for all four questions:

following topics were explored: ITC failures across the number of ITC failures: Pearson’s r¼0.84, p<0.01;

four phases; causes of ITC failures; impact of ITC fail- causes of ITC failures: r¼0.86, p<0.01; effects of ITC

ures; and interventions to reduce these failures and to failures: r¼0.74, p<0.01; and interventions: r¼0.91,

improve information flow. p<0.01 (all N¼18).

Interviews took place between June and August 2008 Tables 2e5 list the main findings for each question of

on the hospital site where each healthcare professional the interview protocol and the number of participants

worked. Ethical approval and written consent was that mentioned each item. This quantification of the

obtained. An interview protocol was developed and qualitative data has been used by previous researchers

piloted in two initial sessions, then distilled into a topic and found to be very useful in highlighting the most

guide by the research team. Interviews were recorded important problems.19 In the following sections and

and transcribed verbatim. tables, data relating to key themes are summarised. The

code letter suffixed to each quotation refers to the

surgeon (S), anaesthetist (A), ward nurse (WN), theatre

nurse (TN) and recovery nurse (RN).

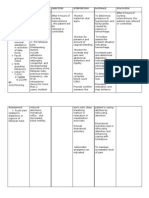

Table 1 Sample of healthcare professionals interviewed

Category Men Women Years of experience ITC failures

Any ITC event involves three components: source,

Surgeons 7 0 4e12

Anaesthetists 4 1 9e26 transmission and receiver. Therefore failure at any stage

Nurses 0 6 6e25 leads to an ITC failure. This is the basis of our classifi-

cation for ITC failures in table 2.20

844 BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:843–849. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 on 7 July 2012. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on December 8, 2021 at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Protected by

Original research

Table 2 Information transfer and communication failures across all phases of care

Classification of failure type with examples and No. of subjects who No. of

Phase of care verbatim quotes said this times

Preoperative Source failures 11 (S¼6, A¼2, N¼3) 13

assessment and < Information at different places

optimisation phase < Consent/notes/investigations missing

< Documentation inadequate

Transmission failures 15 (S¼7, A¼3, N¼5) 24

< Lack of communication between anaesthetic and surgical

teams

< Information not relayed from pre-assessment to theatre

Receiver failures 6 (S¼3, A¼3) 6

< Investigations/specialists’ opinion not checked

Preprocedure phase Source failures 12 (S¼4, A¼3, N¼5) 17

< List changed multiple times

< Incorrect/incomplete name on the list

Transmission failures 8 (S¼3, A¼2, N¼3) 8

< No collaborative network among theatre team

< Lack of communication between ward and theatre staff

Receiver failures 8 (S¼4, A¼3, N¼1) 8

< Equipment/cross match/HDU and ITU bed availability not

checked

< Preoperative checklists not followed

Postoperative phase Source failures 15 (S¼6, A¼4, N¼5) 24

< Postoperative handover not done/incomplete

< Poor/illegible written handover

< Too much information, difficult to differentiate important

from unimportant

copyright.

Transmission failures 3 (S¼1, A¼1, N¼1) 3

< Debriefing does not happen

< Operation notes not transferred

Receiver failures 2 (A¼1, N¼1) 2

< Nurse multitasking, not receiving complete information

Daily ward care Source failures 12 (S¼6, A¼4, N¼2) 20

< Information not available from the nurse (not on the

rounds)

< Notes/observation, fluid charts missing

< Decisions from person leading round unclear

Transmission failures 8 (S¼4, A¼3, N¼1) 12

< Poor communication within and across teams

< Lack of organised process of handing over information

Receiver failures 3 (S¼3) 3

< Care pathways not followed

A, anaesthetists; HDU, high-dependency unit; ITU, intensive treatment unit; N, nurses; S, surgeons.

Preoperative assessment and optimisation phase All healthcare professionals further acknowledged that

Transmission failures were most common as per clini- although opinions are sought from specialists in the

cians; all surgeons acknowledged that there is a lack of process of preoperative assessment, they are seldom

intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary communication. followed up. This leads to operations getting cancelled

Problems identified with the patient in this phase are not as patients are inadequately prepared for surgery.

typically communicated between surgical and anaes- Moreover, multiple modes of information transfer

thetic teams leading to inadequate optimisation of the (letters, personal conversations, telephone communica-

patient for surgery: tions) lead to information loss:

“lots of problems are picked up . but then that is not “Some of the information is available electronically, some

communicated between the preoperative assessment of it is on paper, some of it is verbal from the patient or

team and the surgical team. Similarly there’s a very poor their relatives, some of it is verbal from other medical

communication between the preoperative assessment groups so I think all of the information in one place

team and the anaesthetist” (S1). would prevent errors occurring” (S6).

BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:843–849. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 845

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 on 7 July 2012. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on December 8, 2021 at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Protected by

Original research

Table 3 Causes of information transfer and communication failures

Causes No. of subjects who said this No. of times

Task and technology factors 13 (S¼6, A¼3, N¼4) 16

< Primitive forms of information transfer (ie, paper

medical records, paper investigation forms etc)

< Inadequate mode of communication

< Lack of protocol

Team factors 6 (S¼3, A¼2, N¼1) 6

< Hierarchical obstruction to flow of information

< Poor leadership

Individual factors 13 (S¼5, A¼3, N¼5) 17

< Memory lapses

< Inexperienced staff

< Nurses not empowered to play an active role

< Different competencies between junior doctors

Work environment factors 14 (S¼6, A¼4, N¼4) 17

< High workload/inadequate staff

< Lack of administrative support

< Rapid turnover of healthcare professionals

Organisational factors 11 (S¼4, A¼4, N¼3) 17

< Lack of specialist nurses

< Too many layers in the system

A, anaesthetists; N, nurses; S, surgeons.

Preprocedure teamwork Postoperative handover

Source failures, including poor handover from the ward to Many of the failures uncovered in this phase were due to

copyright.

the operating theatre, were the main problems identified an incomplete handover. Information was missing,

in this phase. For example, information regarding aller- incomplete or there was information overload. The

gies and preoperative medication status is often not postoperative handover process was mentioned by all

transferred, with significant implications on patient safety: participants as informal, unstructured and inconsistent:

“when the patient comes to theatre we take everything off “I think that the problem in postoperative handover is

the heparin, we don’t sort of handover to say the patient most likely to be forgetting to tell somebody . I think

was on heparin when they were in the ward” (WN1). there is scope for more formality and recording of

handover and handover protocols such that you don’t

Eight out of 18 healthcare professionals felt that forget to mention the low blood pressure or to give

communication failures among the operating theatre steroids” (A4).

team prior to the start of the operation led to the

omission of important preoperative checks. Thus In addition, participants reported that the surgical

potentially compromising safety further. team is often not present in the recovery room during

Table 4 Consequences of information transfer and communication failures

Impact of information transfer failures No. of subjects who said this No. of times

Impact on patient 18 (S¼7, A¼5, N¼6) 46

< Mortality/major complications

< Operation cancellations/delays

< Increased length of stay

Impact on team 16 (S¼7, A¼4, N¼5) 22

< Staff stressed, unhappy

< Low morale of team

< Service efficiency declines

Impact on organisation 5 (S¼2, N¼3) 8

< Wastage of resources

< Cost implications

< Unnecessary investigations

A, anaesthetists; N, nurses; S, surgeons.

846 BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:843–849. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 on 7 July 2012. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on December 8, 2021 at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Protected by

Original research

Table 5 Interventions to reduce information transfer and communication failures

Interventions No. of healthcare professionals No. of times

Memory aids 15 (S¼6, A¼4, N¼5) 21

< Checklists/protocols/proformas

< Postoperative communication/handover sheet

Technology interventions 8 (S¼3, A¼4, N¼1) 9

< Electronic information and communication record

< Smart card containing updated patients’ information

System changes 9 (S¼5, A¼2, N¼2) 15

< Email from pre-assessment to surgical team

< Risk assessment unit to be established (joint decision

unit for patient, anaesthetist and surgeon)

Cultural changes 11 (S¼5, A¼3, N¼3) 17

< Increased interdisciplinary communication

< Patient should be part of communication pathway

< Juniors feel free to call seniors

A, anaesthetists; N, nurses; S, surgeons.

this phase, so crucial surgical information may not be Work environment factors were the most common

formally handed over. Furthermore, difficulty in priori- reported causes, followed by task, individual, organisa-

tisation of the fragmented information received by the tion and team factors (table 3):

recovery nurse may lead to important information

getting buried, thus delaying the patient’s recovery and “I think for things to happen the right way it’s got to be

made easy for them to happen the right way. And it has to

discharge.

be part of the way you do things. If it’s an add-on, it gets

Daily ward care dropped . design ways of making sure that things . are

easy to follow by everybody” (S3).

copyright.

The most common ITC failures reported by healthcare

professionals in this phase were source failures followed

Rapid turnover of staff members, stress at work and

by transmission failures. Staff shortages, multiple hand-

lack of administrative support were felt to be the

overs and multiple teams doing ward rounds simulta-

common environmental factors leading to ITC failures.

neously means that information is not fully passed across

Task factors included lack of protocols. Variability and

and within professional groups:

inconsistencies in various organisational processes were

“The main problem here is we don’t always have the mentioned by 11 out of 18 healthcare professionals:

nurse following us when we go around. So it’s difficult to

“Consistent and reliable risk assessment is one of the holy

make an integrated assessment of the patient. It’s difficult

grails of preoperative anaesthesia . but it’s not clear

for us to get to find out what has happened” (S4).

whose responsibility it is” (S6).

Participants also mentioned that information is often Effects of ITC failures

fragmented. Some of it is recorded in the patient’s All the participants said that ITC failures can directly or

medical notes, or in the drug charts and some passed on indirectly lead to patient harm (table 4). Some partici-

as verbal instructions, which makes it difficult to access. pants went to the extent to say that nearly all surgical

In addition, healthcare professionals also acknowledged disasters can find their origins in ITC failures:

the lack of communication between the surgical team:

I think what people don’t appreciate is that information

another classic example that we see is that patients transfer problems can make a difference between life and

who’ve had a low anterior resection, may have an anas- death. Communication is seen as a very soft issue and

tomosis and no one should be digitating them, or giving people think that it can’t have much of a bearing on

them anything PR, and you know a house officer or outcomes and I completely disagree with that. The

a junior member of the staff gives them a rectal suppos- sooner you speak to somebody about a certain problem

itory . there are issues with communicating post- the sooner the action is taken, the sooner the problem is

operative management to everyone involved (S5). sorted out. The patient will obviously have a better

outcome. And all the sooner, sooner, sooner, depends

Causes of ITC failures upon how the information is transferred (S1).

We classified causes of these ITC failures in accordance

with the seven-level framework classification of contrib- Beyond patient harm, ITC failures were also thought

utory factors proposed by Vincent21 [14]. to destroy team dynamics and lead to stress:

BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:843–849. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 847

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 on 7 July 2012. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on December 8, 2021 at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Protected by

Original research

“more stress for the nurses stress for the patient, stress for DISCUSSION

everyone, because there’s no proper communication”

(WN2). This is the first prospective study to systematically identify

ITC failures across the entire surgical care pathway. Its

They can also have an impact on the organisation

qualitative approach enabled these issues to be explored

through unnecessary investigations, wastage of resources

in a way that would not have been possible with quanti-

and theatre list cancellations, which can all potentially

tative methods. Importantly, this study confirms earlier

result in increased healthcare costs:

findings that ITC failures are common in surgery, are

“the cost effectiveness of theatre time, if the operation is equally distributed along the whole continuum of care10

cancelled because the notes are not there or the wrong and can cause patient harm.22 Checklists, system changes

patient has been booked so it’s all that theatre time that’s and technological interventions can improve communi-

been wasted and being paid for” (RN2). cation and information transfer.23e25

More significantly, this study goes beyond other studies

Interventions focused only on the operating theatre and helps address

There is a widely shared view among participants about the bigger picture of this problem. We found that there

the need for interventions to improve information flow was a lack of communication between different teams, and

and reduce ITC failures across the whole continuum of in cases where information was available, it was either

care. Structured, organised, transparent and efficient difficult to access or fragmented. The causes and effects of

ITC was described as the basis for all interventions. these failures identified in this study also echo the findings

Regarding the content of interventions, participants of previous work.26 Apart from patient harm, the partici-

mentioned checklists, smart card, cultural and system pants mentioned the healthcare system seems to suffer

changes (table 5). Checklists have been shown to change enormous inefficiencies because of poor ITC practices.

the outcome of the patients.11 12 Almost all participants Healthcare professionals did have a clear view about

emphasised the need for the development of tools for the interventions to improve the process of information

standardisation of information transfer. Participants felt transfer so that it is more structured and systematic.

copyright.

that there should be a central information repository, In particular, checklists were thought to have great

which should have all the relevant patient information potential e perhaps reflecting the success of the checklist

and could be accessed when required: in other industries.27 This is in accordance with a recent

WHO study which found that implementation of

let’s imagine a smart card that the patient carries with

a surgical safety checklist was associated with a significant

them and you put into a machine and you add to it, well

improvement in patient safety practices. The mandatory

at this phase I want you to give a litre of saline . so all

the information is there and the recovery nurse doesn’t introduction of this WHO checklist in England in 2010

have to say “what did he say”, they can look and say well may help to improve some of the communication and

actually this is the information that we need to acquire information transfer processes in every operating theatre

for this patient, this is the management for that patient across the countrydwe have yet to see its outcomes.

(A4). Despite highlighting the simple measures like checklists,

study also identifies that major organisational, system and

A need for cultural and system changes also emerged cultural changes are needed to enhance the ITC.

through the interviews, that is, a culture of openness, A revamp of preanaesthetic unit, improved communica-

transparency where everybody can raise their concern tion between the preanaesthetic unit and the surgical

and is not afraid of the seniors. In addition, there should team, clarity of responsibility were a few of the interven-

be a system overhaul, that is, pre-assessment communi- tions identified. This finding echoes the conclusions

cation with the surgical team, automatic alerts, surgical from previous studies.2 26 28 29 In their study, Williams

care pathway checklist/electronic list. It was felt by the et al26 also suggested major change in institutional habits

participants that through improved communication and to improve the ITC. Process mapping has been used in

better teamwork, even mortality and morbidity can be the past to improve the current practices and decrease

reduced: the errors. The study by Aulbach et al30 showed the

improvement in blood transfusion safety by process

so you cannot change the fact that complications will

mapping and subsequently implementing wireless elec-

occur in surgery, but you can definitely change what the

outcome of the complications with good communication tronic transfusion verification technology.

and good information transfer. And good teamwork This study does have limitations. An obvious limitation

between the various people such as surgeons, anaesthe- was the fact that we interviewed a small sample of

tists, the nurses and doctors, if you improve that then you surgeons, anaesthetists and nurses and there is a possi-

can definitely reduce the postoperative mortality (S1). bility that their views may not have captured all of the

848 BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:843–849. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886

BMJ Qual Saf: first published as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 on 7 July 2012. Downloaded from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/ on December 8, 2021 at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Protected by

Original research

relevant concepts. However, our sampling strategy and 6. Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, et al. The quality in

Australian Health Care Study. Med J Aust 1995;163:458e71.

methodology provided rich information from a range of 7. Healey AN, Undre S, Vincent CA. Developing observational

healthcare professionals and the fact that we reached measures of performance in surgical teams. Qual Saf Health Care

2004;13(Suppl 1):i33e40.

saturation, that is, no new themes emerged, supports the 8. Lingard L, Espin S, Whyte S, et al. Communication failures in the

generalisability of our findings. Another fact that needs operating room: an observational classification of recurrent types and

effects. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:330e4.

to be taken into account is that this study is based on 9. Sevdalis N, Forrest D, Undre S, et al. Annoyances, disruptions, and

subjective assessment of the clinicians, but these clini- interruptions in surgery: the Disruptions in Surgery Index (DiSI). World

J Surg 2008;32:1643e50.

cians had a varied amount of experience and we believe 10. Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, et al. Patterns of

that it represents the most common ITC errors communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J

Am Coll Surg 2007;204:533e40.

throughout the surgical care pathway. We also accept 11. Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to

reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med

that important communication failures occur across the 2009;360:491e9.

primary/secondary care boundary, before admission and 12. Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, et al. Improving

communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care

on discharge; these need to be addressed in subsequent 2003;18:71e5.

studies. 13. Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract

1996;13:522e5.

Further research should build upon this study by 14. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks,

conducting an observational study of ITC failures within California: Sage, 1994.

15. Kuper A, Lingard L, Levinson W. Critically appraising qualitative

the surgical system. We believe that this study may also research. BMJ 2008;337:a1035.

guide the development of measures to evaluate ITC 16. Nagpal K, Vats A, Ahmed K, et al. A systematic quantitative

assessment of risks associated with poor communication in surgical

failures and in subsequent interventions to mitigate their care. Arch Surg 2010;145:582e8.

effects. Understanding and addressing these failures will 17. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and

guidelines. Lancet 2001;358:483e8.

enhance the quality and safety of patient care across the 18. Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 2nd

entire surgical pathway. edn. London: Routledge, 1995.

19. Arora S, Sevdalis N, Nestel D, et al. Managing intra-operative stress:

Contributors KN, KM, NS, CV were involved in conception and design, analysis what surgeons want from a crisis training programme. Am J Surg

2009;197:537e43.

and interpretation of data. KN, HW, SA, AV were involved in acquisition,

20. Flin R, O’Connor P, Crichton M. Safety at the Sharp Endda Guide to

analysis and interpretation of data. SA, KN, AV, HWW drafted the initial article. Non-technical Skills. Ashgate, 2007.

KM, NS, CV revised it critically for important intellectual content. KN, SA, AV,

copyright.

21. Vincent C. Understanding and responding to adverse events. N Engl

HWW, NS, CV, KM had final approval of the version to be published. J Med 2003;348:1051e6.

22. Christian CK, Gustafson ML, Roth EM, et al. A prospective

Funding The research described here was supported by the National Institute study of patient safety in the operating room. Surgery

of Health Research (NIHR) and the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences 2006;139:159e73.

Research Council (EPSRC). 23. Catchpole KR, de Leval MR, McEwan A, et al. Patient handover from

surgery to intensive care: using Formula 1 pit-stop and aviation

Competing interests None. models to improve safety and quality. Paediatr Anaesth

2007;17:470e8.

Ethics approval The project protocol was submitted to the National Research 24. Lingard L, Regehr G, Orser B, et al. Evaluation of a preoperative

Ethics Service (Joint UCL/UCLH Committees on the Ethics of Human checklist and team briefing among surgeons, nurses, and

Research). They felt it was a ‘service evaluation’ study so did not require anesthesiologists to reduce failures in communication. Arch Surg

ethical approval. REC reference number: 08/H0715/112. 2008;143:12e17; discussion 18.

25. Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, et al. A randomized,

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed. controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and

sign-out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am

Coll Surg 2005;200:538e45.

REFERENCES 26. Williams RG, Silverman R, Schwind C, et al. Surgeon information

1. Undre S, Arora S, Sevdalis N. Surgical performance, human error and transfer and communication: factors affecting quality and efficiency of

patient safety in urological surgery. Br J Med Surg Urol 2009;2:2e10. inpatient care. Ann Surg 2007;245:159e69.

2. Vincent C, Moorthy K, Sarker SK, et al. Systems approaches to 27. Boorman D. Today’s electronic checklists reduce likelihood of crew

surgical quality and safety: from concept to measurement. Ann Surg errors and help prevent mishaps. ICAO J 2001;1:17e36.

2004;239:475e82. 28. Nagpal K, Arora S, Abboudi M, et al. Postoperative handover:

3. Kohn L. To err is human: an interview with the Institute of Medicine’s problems, pitfalls, and prevention of error. Ann Surg

Linda Kohn. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 2000;26:227e34. 2010;252:171e6.

4. Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in 29. Patterson ES, Roth EM, Woods DD, et al. Handoff strategies in

hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care

II. N Engl J Med 1991;324:377e84. operations. Int J Qual Health Care 2004;16:125e32.

5. Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, et al. Incidence and types of 30. Aulbach RK, Brient K, Clark M, et al. Blood transfusions in critical

adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care care: improving safety through technology & process analysis. Crit

2000;38:261e71. Care Nurs Clin North Am 2010;22:179e90.

BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:843–849. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000886 849

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- CBT Study GuideDocument10 pagesCBT Study Guideplethoraldork100% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Nabh Training Topics For All The Departmental StaffDocument4 pagesNabh Training Topics For All The Departmental StaffMr. R. Ramesh75% (8)

- Course Name Course Code Lecturer: General Radiographic Instrumentation DBR 11002 DR Suffian Bin Mohamad TajudinDocument4 pagesCourse Name Course Code Lecturer: General Radiographic Instrumentation DBR 11002 DR Suffian Bin Mohamad Tajudinsyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Ankylosing Spondilitis Latest 25 SepDocument12 pagesAnkylosing Spondilitis Latest 25 Sepsyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Sectional Anatomy Sectional AnatomyDocument34 pagesSectional Anatomy Sectional Anatomysyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Asignmnt Patho IDocument2 pagesAsignmnt Patho Isyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Script BiDocument2 pagesScript Bisyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Keratin and Melanin PigmentsDocument2 pagesKeratin and Melanin Pigmentssyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Advances in Fai ImagingDocument19 pagesAdvances in Fai Imagingsyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity and Abnormal Blood Glucose Among Healthy Weight AdultsDocument6 pagesPhysical Activity and Abnormal Blood Glucose Among Healthy Weight Adultssyafiqa abdullahNo ratings yet

- Article: Matthew K. Abramowitz, Michal L. Melamed, Carolyn Bauer, Amanda C. Raff, and Thomas H. HostetterDocument7 pagesArticle: Matthew K. Abramowitz, Michal L. Melamed, Carolyn Bauer, Amanda C. Raff, and Thomas H. Hostetterdianaerlita97No ratings yet

- AnisokoriaDocument5 pagesAnisokoriaNurunnisa IsnyNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Hyperthyroidism by Traditional Medicine TherapiesDocument3 pagesTreatment of Hyperthyroidism by Traditional Medicine TherapiesPirasan Traditional Medicine CenterNo ratings yet

- Dose MonitoringDocument60 pagesDose MonitoringNovan HartantoNo ratings yet

- NCP ConstipationDocument3 pagesNCP ConstipationNika LoNo ratings yet

- Ulnar Nerve Injury, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument30 pagesUlnar Nerve Injury, Diagnosis and TreatmentsherysheryyNo ratings yet

- Basal GangliaDocument48 pagesBasal GangliaMudassar Roomi100% (1)

- Care Map UtiDocument1 pageCare Map UtiJonathonNo ratings yet

- Notre Dame of Educational Association.Document10 pagesNotre Dame of Educational Association.Maui TingNo ratings yet

- Medical Vocabulary - HOSPITALDocument4 pagesMedical Vocabulary - HOSPITALBianca AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Health Communication and Mass Media CH1 PDFDocument17 pagesHealth Communication and Mass Media CH1 PDFShamsa KanwalNo ratings yet

- DyalisisDocument24 pagesDyalisisAbdulla Abu EidNo ratings yet

- PromixineDocument2 pagesPromixineStelaA1No ratings yet

- Surgery Illustrated - Surgical Atlas: Mainz Pouch Continent Cutaneous DiversionDocument25 pagesSurgery Illustrated - Surgical Atlas: Mainz Pouch Continent Cutaneous DiversionAbdullah Bangwar100% (1)

- Tim Richardson TMA02Document6 pagesTim Richardson TMA02Tim RichardsonNo ratings yet

- Epilepsy SurgeryDocument13 pagesEpilepsy SurgeryDon RomanNo ratings yet

- EcgDocument18 pagesEcgDelyn Gamutan MillanNo ratings yet

- Class II Division 1 Treatment Using A Two-Phase Approach - A Case Report.Document16 pagesClass II Division 1 Treatment Using A Two-Phase Approach - A Case Report.ryanfransNo ratings yet

- 柳奇學姐提供的Mode of Mechanical VentilatorDocument79 pages柳奇學姐提供的Mode of Mechanical Ventilatorapi-25944730100% (10)

- Definition, Vocabulary and Academic Clarity-1Document26 pagesDefinition, Vocabulary and Academic Clarity-1umarah khanumNo ratings yet

- HepatitisDocument8 pagesHepatitisudaybujjiNo ratings yet

- TFN Joyce TravelbeeDocument33 pagesTFN Joyce Travelbeechryss advinculaNo ratings yet

- Temporo-Mandibular Joint Complex Exercise SuggestionsDocument9 pagesTemporo-Mandibular Joint Complex Exercise SuggestionsClaudia LeperaNo ratings yet

- Caregiving Body TemperatureDocument69 pagesCaregiving Body TemperatureDanny Line100% (1)

- Bionic Eye AbstractDocument3 pagesBionic Eye Abstractvamsi28No ratings yet

- Pysch Nursing ReviewerDocument72 pagesPysch Nursing ReviewerKristeen Camille ValentinoNo ratings yet

- Ectopic PregnancyDocument2 pagesEctopic PregnancyRex Dave Guinoden100% (1)