Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Reliability of Hadith and Gospel Records

Uploaded by

Bilquees Suleman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views12 pagesTHE HADITH AND THE INJIL (1915)

Original Title

The Muslim World vol. 5

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentTHE HADITH AND THE INJIL (1915)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views12 pagesThe Reliability of Hadith and Gospel Records

Uploaded by

Bilquees SulemanTHE HADITH AND THE INJIL (1915)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

THE WAR AND ISLAM 345

War has three dangerous enemies, which are more than

its match: the Russian knout, the English pound, and

the universal indolence of Moslem races. As a national

state Turkey still possesses vital forces. Islam as a.

world-power is an extinct volcano ; in the depths of its

crater there may still be rumblings, but i t has lost any

power of eruption.”*

Here the writer serioudy quotes a report in the

Vossische Zeitung (March 18th and 19th, 1915) of a new

Mahdi in the Sudan called Derwish Mabur el Afl. “ He

is said to have annihilated the British troops under

General Hawley in December, and by the beginning of

March to have conquered tohewhole of the Sudan with

the capital Khartoum and a great part of Nubia. Dan-

gerous as this success is for the British Government in

the Nile Valley and although it plays directly into the

hands of Turkey, it cannot be regarded as the result of

the summons to the Holy War. For this revolt would

have broken out apart from the Turkish jihad, and even

if Turkey did succeed in conquering Egypt it would

have to suppress this rising in the Sudan.”t His con-

clusion is, that in view of the unparallelled changes in

national relationships through the war, “ t h e task of

Missions to Moslems will assume a new aspect, consequent

on the contrasted relations of the European powers to

Islam.”$

In the supplement to the May and June numbers of

the Allgemeine Missions-Zeitschrift, Herr Enderlin, of the

Sudan Pioneer Mission, founded a few years ago in

Assuan, gives a sketch of “ Tendencies and Currents in

Egyptian Islam.” He is of opinion that Mohammedan

sympathies are with the German cause, and that they pray

“ especially for Hag (Mecca-Pilgrim)Mohammed Ghalyum

-i.e., the Emperor Wilhelm.” Some years since, in a

remote village of Upper Egypt, an Egyptian gentleman

who first received him with suspicion, on finding he was a

German brought out a bottle of scent with a picture of

the Sultan Abdul Ha8midand the German Emperor arm

in arm, saying, “ They are friends, they belong together ” ;

and the company responded, “May Allah lengthen his

* Ibid., p. 163. Ibid., p. 154. $ Ibid., p. 157.

346 THE MOSLEM WORLD

days.” To the writer (p. 63) “it =ems aa if Germany were

destined by the will of God to present to Mohammedans

a better picture of Christianity ” than Russians or Anglo-

Saxons. It may be added that this last article is in a

feuilleton of the review, and the passages quoted are in

small print ; so it may be presumed that they are not

regarded as of first class authority.

The solution of the problem thus presented to German

Christians must wait for the verdict of the peace settle-

ment, when that comes. But if the war so far has shown

that national and religious oppositions are very far from

running parallel, we may hope that any change in

political relations between Germany and Turkey need

not bar the rising tide, hitherto perceptible in German

missionary circles, of interest and sympathy towards the

Christian witness to the Moslem world.

H. U. WEITBRECHT.

A VETERAN’S MESSAGE 347

A VETERAN’S MESSAGE.

-. .0:-

IN the April number of THEMOSLEMWORLDwe had a

greeting from the Bishop in Jerusalem, who was just

girding on his armour for the new work which lay before

him. The Editor has kindly asked me for a brief message

from one who is just laying aside his armour and retiring

from the Front. To my great sorrow, the doctors have

forbidden me ever to return to Persia, and ill-health

makes it necessary for me to leave the firing line and

to join the ranks of those who are engaged at the home

base. It is some comfort to realise that the work and

prayers of those a t home are needed as much as the

labours of those abroad. We are being constantly re-

minded that the present war will be won in the workshops

quite as much as in the trenches. The only thing that

matters is that each citizen who rejoices in his heavenly

citizenship should be in the place chosen for him to

faithfully serve his King.

The thought uppermost in my mind, which I should

like to pass on to you, is the absolute certainty of the final

victory of our King. We are on the winning side, however

long the final victory may be delayed. Christ has con-

quered the forces of sin and Satan. We see not yet all

things put under Him, but that “ not yet ” speaks to us

of the crowning day that is coming, in which every

stronghold of error shall be cast down, and every tongue

- e v e n in what are now Moslem lands--shall confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father !

It is sometimes helpful to look back as well as to look

around. My thoughts go back to a voyage up the

Persian Gulf nearly twenty-six years ago. That grand

old veteran, Bishop French, was witnessing for his Master

a t Muscat, and was, a few months later, to lay down his

life for Him there. But with that solitary exception the

Banner of the Cross was being uplifted nowhere in the

348 THE MOSLEM WORLD

Persian Gulf between Karachi and Baghdad. Zwemer

and Cantine had not yet appeared on the scene to pros-

pect for the Arabian Mission. Bruce, with two col-

leagues, was at work in Julfa, an Armenian village close

to Tsfahan, and the C.M.S. had then no other work in

Persia. The Bible Society’s work in the Persian agency

was almost in its infancy. The American Presbyterian

Mission in Northern Persia was much less fully developed

than it is to-day. There were no special signs that an

era of progress was a t hand. But to-day we thank God

for the vigorous work that for many years has been

carried on at Muscat, Bahrein, Busrah, Kuweit, and

elsewhere, by missionaries of the Arabian Mission. Some

of them already rest from their labours ; but their works

do follow them. One of them, George E. Stone, who

died at Muscat, left a message which has often been an

encouragement to others, “ We are getting the dynamite

under this rock of Islam, and some day God will touch it

0 f l . f ’ ’ The C.M.S. work in Persia has been greatly

developed during the past quarter of a century. Hospitals

for men and women have been built in the Mohammedan

cities of Jsfahan, Yezd, and Kerman, while educational

work has been established in those centres. Faithful

work has also been done for some years at Shiraz, though,

alas, that scene of Henry Martyn’s labours is a t the

present time unoccupied by any ambassador of the

Cross. Itinerating tours have proved that there is in

the country an open door for evangelisation everywhere.

Medical missions do more than unlock the doors ; they

take them off their hinges. The BAbi and Baht% move-

ments, and the persecutions to which their adherents

have been subjected, have in many directions created a

craving for religious liberty, and stimulated a search for

truth. God has wrought and is manifestly working with

us to-day ; let us take courage, making the words of

Henry Martyn our own, “ I f there is one thing which

refreshes my soul above all others, it is that I shall behold

the Redeemer glom‘ously triumphant at the winding up of

all things .f ” That time may not be distant.

CHARLESH. STILEMAN

July, 1915. (Bishop in Persia).

MOHAMMEDAN TRADITION AND GOSPEL 349

MOHAMMEDAN TRADITION AND GOSPEL

RECORD

THE HADiTH AND THE INJIL*

[In this tjrticle, sections I and I1 lay claim to no originality of research.

They are simply and solely a study on Goldziher’s epoch-making

essay on the Hadith in his ‘‘ Mohammedanische Studien,” vol. 11. ;

and the concentration of the attention on certain conclusions which it

seems right to draw from the things there proved. .

In section 111 the attention of the reader is called to the bearing

of the concluaiona thus reached upon the queetion of the reliability of

some of the earliest Christian documents.-W. H. T. G.]

THEREis nothing in Christianity which particularly

invites comparison with the Koran, as a book in which

t.he Deity is ostensibly the sole speaker throughout, and

which has come down to us practically verbatim from its

promulgat,or. More commensurate are the Mohammedan

Traditions and the Gospels. In both of these the basis

is narrutive, or reports of sayings. Both have come down

to us, to a greater or less extent, through oral tradition

in the first stages, their committal to writing and authori-

sation being later. Both directly concern the all-

important subject of the life and teaching of a religion-

founder. And both (though in different ways) are

treated a8 sacred books ; for although modernising

Moslems refuse to consider any book except the Koran

absolutely authoritative, the vast majority still regard

their Bukhari as a Book on which an oath may just as

rightly be taken as the Koran itself.

It is strange, therefore, that with these u prim’

resemblances, the two sets of record8 should present

such immense and citriking differences. The most im-

portant of them are (1)the much more modest dimensions

of the Christian records as compared with the Moslem ;

(2) the lateness with which the Moslem records were

* See “Trendation of the Chapter on Hadith iind the New

Tcatament,” by F. &I. Y. S.P.C.K. London, 1902.

350 THE MOSLEM WORLD

collected into book form as compared with the Christian ;

(3) the absence in the Gospels of i s n d (i.e., the citation

of the pedigree of each report, whether of incident or

saying), and the all-pervading and all-important part

played by isndd in the Traditions.

It is these differences which force upon us the question

of the relative reliability of the records which we call

“ the Gospels,” and the records which are called “ the

Hadith.” And this is the general subject of the present

article. But before we can discuss this definitely, it will

be necessary to concentrate attention exclusively on the

Hadith, a8 being less fa,miliar to us, both in history,

form, and content ; deferring the comparison between

Hadith and Gospel until the end.

I.

All information whatsoever about matters historical,

theological, social, ritual, legal, etc., was passed down

by the Moslems through the first centuries of Islam in

the form of oral traditionp, each tradition (or hadith,

literally “ talk ”) consisting of (a)the pedigree ( i m d d ) ,

( b ) the text (main). The former gives the chain of trans-

mitters connecting the final recorder with the original

speaker or narrator. The latter gives the information

thus supplied, usually in the shape of a short paragraph,

often consisting of no more than a few sentences, some-

t.imes a single sentence.

The volume of these t,raditions grew in the course

of a few centuries to be quite prodigious, running into

hundreds of tho.usands, and touching upon every imagin-

able subject, however great and however trivia.1. The

efforts of the great Traditionists, like al-BukhEiri, were,

therefore, far more efforts of criticism than of collection,

The difficulty was not. the getting, but the sifting.

But what was their canon of criticism ? That is the

important thing for us to know.

In the first place, their criticism was never, under

any circumstance, intermil. Provided that the chain of

transmitters was sound, no intrinsic improbability, im-

possibility, or absurdity in the substance of the tradition

itself, was allowed to weigh for a moment. Even con-

MOHAMMEDAN TRADITION AND GOSPEL 351

tradictiona were allowed to stand, and the existence of

them created another branch of the trditionist science,

the task of which was to explain and harmonise the

differences away. We see in this total absence of intemzcrl

criticism a grave defect in the Moslem method. For

although our own Biblical critics have undoubtedly relied

too much on internal criteria, and have probably in

consequence proceeded very one-sidedly and precar-

iously, it ia still more evident that a cautious employment

of the internal method by the Moslems, to reinforce the

external one, would have saved them from an infinity of

ddu&on.

In the second place, then, their method waa wholly

external; that is to say, it consisted in criticising the

genuineness of the chain of guarantors. To some extent

this criticism was impersonal-e.g., if the chain exhibited

chronological or other impossibilities (the birth-years,

death-years, and habitations of the guarantors being

known), the tradition was called in question or put on

to the black list. But a still mcre important criterium

waa the personal one, and consisted of a naqd ir-rijdZ,

or critique of the guarantors themselves ; their truthful-

ness and general reliability.

Admitting, with admiration, the wonderful learning

which such a method involved, and its success in the

impersonal aspect, how are we to account. for the serious

failure of Moslem criticism in regard to the traditions ?

We have already seen one cause in its resolute barring

of internal evidence. A second, and more important

cause (it seems to us), wm the breakdown of even its

external critique, when i t came to criticising the trans-

mittera themselves.

Generally speaking the Moslem critic found himself

less inclined to criticise the reliability of ir-rijul (" the

men") the farther back he went. His own contem-

poraries and the preceding generation or two would be

the most liable to suspicion. The Tiibi'iin (or second

generation after Mohammed) were not to be lightly

touahed with suspicion. But the Sahiiba, or contem-

poraries, were practicaZZy exempt. For it is a surprising

fact that even where there were admitted suspicions,

352 THE MOSLEM WORLD

they were never allowed, actually and practically, to

weigh. We shall see examples of this strange fact in

moment; but meanwhile let us clearly realise the

drastic results of such a defect. For it is manifest that

impurity a t or near a source is far more important than

lower down. The Moslem criticism of “ the men”

should, therefore, have been m e unsparing in pro-

portion as it approached the source; whereas in fact,

owing to the practical impeccability attributed to the

Companions, it was relaxed exactly in proportion as it

was needed, and suspended exactly at the point where

it became absolutely indispensable. For it is now certain

that the three or four Companions whose contributions

to the traditions probably exceed all the rest put together,

are precisely those upon whose word least reliance can

be placed.

This last point is the one which must now engage

our particular attention. If we study for a moment the

chronological table of names, with their dates, which

accompanies this number, we are a t once struck by the

fact that nearly all the best of the Companions died off

between twenty and thirty years after the death of

Mohammed, namely, during the period of the wars, both

foreign and civil, which completely fill Islamic history

down to the establishment of Umayyad power. And it

is precisely these Companions, whose veracious recol-

lections of speech and event we should first desire to

possess, who are represented by the isniid’s as having

passed down to us nothing, or next to nothing. Still

more remarkable is the fact that even one of this class

like Sa‘d b. WaqqB, who survived some twenty years

into the Umayyad period, has handed down little or

nothing. To whom then do we owe (or are represented

as owing) the vast bulk of the traditions about Moham-

m e d ? To the younger Companions, and above all to

three men, Abti Huraira, Ibn ‘Abbcis, and Anas b. MBlik,

to which names may be added that of ‘A’isha,the favour-

ite wife of Mohammed. No objection can be levelled

against the latter on the score of brevity of companion-

ship, or slightness of intimacy, with Mohammed. The

objection to her is her utter ~~nscrupulousness,her

MOHAMMEDAN TRADITION AND GOSPEL 383

passionate partizanship, and general want of sound

character. But the former three, in addition to certain

grave personal defects, were only in touch with Moham-

med for the last few years of his life, and in those days

were exceedingly juvenile persons at that. Ibn ‘Abbb,

to whom we owe thousands of traditions on all manner

of subjects, and especially the Prophet’s own alleged

explanations of Koran texts and alleged legal decisions

(that is to say, traditions involving masses of most

intricate detail), was only fourteen years of age a t

Mohammed’s death! and his contact with him was

limited to the last four years of his life, that is to say,

from the tenth or eleventh of his life ! Abii Huraira,

to whom also thousands of traditions are ascribed, only

islamised four years before Mohammed’s death, and was

a youth of no mark whatever during that time. Anas

b. Malik, likewise a man of no birth, standing, or educa-

tion, was only nineteen a t the death of Mohammed. Yet

Caetani estimates that more than half of A1 BukhWs

7275 traditions are ascribed to these three youths-one

might almost say, boys! In Tabari’s monumental his-

tory Ibn ‘Abbas is cited 286 times, Abii Huraira 52, An-

47,while the first four Khalifas are not cit,ed so much as

once.

The biographer Al Waqidi (died A.H. 207) is evidently

struck by this fact., and accounts for it by saying that

the older Companions died “before there was any

necessity of referring to them.”* But in another place

he attributes the fact to a much morc suggestive cause,

namely, “ their fear ” (Le., of giving forth traditions

erroneously).t Thus ‘IJmar said, “ If it were not that I

feared lest I should add to the facts in relating them, or

take therefrom, verily I would tell you.” Similar words

are attributed to ‘Uthmi%n,$Ibn Mas‘tid and Ibn Zubair.

No such modesty, unfortunately, characterised the less

responsible Abii Huraira, Ibn ‘Abbiis, etc.--least, of all

the irrepressible ‘A’isha : their popularity and fame,

as we shall see, depended on the substitution of an

extreme boldness, not to say effrontery, for this fear.

* Quoted in Muir’s Life.”

“ (Intro., p. L., note ; new edition).

t Ib., p. LXVI.,note. $ Ib., p. XXXVI., note.

Y

364 THE MOSLEM WORLD

Still more significant is a remark attributed t o Sa‘d

b. Waqqa. He waa dmost the only one of the more

reputable Companions who survived well into the period

of the Umayyads, and i t is, indeed, very significant that

not even from him do we receive traclitions-especially

when we read the reason which he himself gives for hie

abstention. “ I fear,” he said, “ that if I tell you one

thing, ye will go and add thereto, &B from me, a hun-

dred!”* Frankness could no further go in the way

of commentary upon the proceedings of Trditioniste,

within eighteen years of the death of ‘Ali. Clearly the

less scrupulous were already hard at work ; and clearly

(moreover) they were not only inventing traditions but

also isna’s to match (cf., “ as from me,” above). The

point is important ; for i t shows (1) how little objective

value an apparently impeccable isnad may really possess,

(2) how little it need really safeguard the tradition

which i t vouches, and (3) how futile is any argument for

reliability which is based on the absolute integrity of

the first generation of Moslems. For it is surprising

that as early as this we find indications of the unscrupu-

lousness to which Sa‘d alludes so candidly. Even in

‘Uthmgn’s time, less than twenty-four years after

Mohammed’s death, the thing had begun ; witness

‘Uthman’s strmge and significant command : “ It is

not permitted to any one to relate a tradition as from

the Prophet which he has not already heard in the time

of Abii Bakr and ‘Umar ! ” The words are their own

commentary.

We may be pardoned for thinking, in particular, that

these caveats were not without tacit allusion to the very

traditionists whom we have already mentioned, especially

Aba Huraira, Ibn ‘Abbiis, and ‘A’kha. I n the case of

one of them, indeed, Abii Huraira, there are many

indications of the low opinion hold by his contemporariefi

of his truthfulness and reliability, which definitely justify

the suspicion. If similar indications are wanting in the

caae of Ibn ‘Abbkq, the interest of his descendants in

protecting the ancestor of their dynasty from everything

and anything that might discredit him, is sufficient to

* Ib., p. LXVI., note.

MOHAMMEDAN TRADITION AND GOSPEL 355

account for the fact. For from all we know of the man*

and the circumstances of his conversion, and from a

rational judgment on his work, it is impossible to place

him any higher than Abii Huraira.

If we place the allusions of his cont,emporaries t.0 Abii

Huraira in an appendix,? it is not that they are of

secondary importance, but only because their dispro-

portionate fulness might disturb the flow of our argu-

ment. On the contrary, they are of first-rate importance

and should be most carefully studied. The points to

notice here are :-

(1) if, in the face of these contemporary strictures,

the name of Abii Huraira is passed by later criticism m

beyond criticism, simply on the score of his being a

Companion, this shows that later criticism simply had

a blind spot. in relation to the first generation of Moslems.

And this is the more serious, for :

(2) the nearer falsification can be proved to the

source the mwe serious it becomes. But here we have

evidence of falsification at the very source. If a well-

spring has been poisoned, what avails the most careful

guardianship of the streams and reservoirs below i t ?

Yct Bukhsri increased the strictness of his n q d QT

r i j d the later their lives occurred, diminishing the strict-

ness to zero as he ascended the stream. We now see

that both on general and particular grounds the process

should have exactly been reversed. The Fathers of

Mohammedan tradition were, in one word, entircly

unworthy of such blind trust.

Nor, as we descend the stream again, do we find the

banks and reservoirs well-guarded. Goldziher, in his

epoch-making study on the Traditions in “ Moham-

medanische Studien,” has shown with what utter un-

scrupulousness the business of tradition-falsification went

on during the Umayyad and the first part of the ‘Abbasid

period. Now political partisans coined hadith’s to

In order to acquire authority ior a certain tractition concerning

the details of certain ritual lustrstions at night, he claims to have

more than once passed the night in the aame bed with Mohammed

and one of his wives, and thus to have observed the lustratione iu

question ! It is Bukhti who preserves this story.

t See appendix to thia article.

366 THE MOSLEM WORLD

support various political parties, and now, similarly,

hadith’s were coined to support the various schools of

jurisprudence (fiqh), or to supply material for the lawyers

upon which to base their systems. The number of tradi-

tions grew from thousands to tens and hundreds of

thousands. So gross was the business that Moslems do

not deny, and never have denied, that fabrication went

on ; the whole raison d’6tre of al-Bukh8ri waa to reduce

these hundreds of thousands to a very few thousands, a

confession in itself to the correctness of the verdict of

modern times. But this is not the point. The real

point is not that fabrication went on, but that there is

the gravest suspicion that the best men were not above

it, and that, therefore, even Bukhhri’s critique and whole

method are still further compromised. It is well worth

while pausing to consider this point more in detail.

The times were in many respects out of joint in the

world of Islam. The House of Umttyy which, with

Mu‘gwiyah, had seized the Khalifate were reckoned by

pious Moslems as usurpers on the one hand and semi-

heathen on the other, worthy sons of those reprobate

Meccan aristocrats whose conversion to Islam had only

been secured by force of circumstance and hope of gain.

It was absolutely necessary for such men to get religious

sanction for their rule. The oracle of Hadith was freely

manipulated to this end, and the ‘Ulama in the govern-

ment-offices were pressed into the service of giving

Pmayyad rule a religious complexion in this and other

ways. The strictest Moslems, therefore, refused entirely

to serve under the Khdafd’ al-j a w (Tyrant-Khalifas).

And yet it was not entirely men of their own kidney who

consented thus to serve. Under such circumstances

there will always be found men of a mediating turn of

mind who will make the attempt to serve God in Mam-

mon’s court, and Mammon for God’s sake.

Of these wm one who is the typical traditionist of his

generation,* Zuhri (d. 125). This man’s name occurs in

the isntid’s of his generation more frequently than any

other. And this very fact is enough to shalie our already

* Just as ‘Urwa b. Zubair was typical for the previous generation,

and Ibn . A b b t and the others we have mentioned for the firat.

You might also like

- The Blood of the Moon: Understanding the Historic Struggle Between Islam and Western CivilizationFrom EverandThe Blood of the Moon: Understanding the Historic Struggle Between Islam and Western CivilizationNo ratings yet

- The Apology of Timothy IDocument174 pagesThe Apology of Timothy ISupernova_Pegasi100% (1)

- Islam and Christianity 1918Document2 pagesIslam and Christianity 1918Mia AmaniahNo ratings yet

- Apology of Al-Kindi Trns Muir PDFDocument122 pagesApology of Al-Kindi Trns Muir PDFIdo MudahiNo ratings yet

- Eng Speaking Orientalists j.1478-1913.1963.tb01156.xDocument20 pagesEng Speaking Orientalists j.1478-1913.1963.tb01156.xNoor UD DinNo ratings yet

- Muhammed (Pbuh) in The BibleDocument164 pagesMuhammed (Pbuh) in The BibleAnsari Salman0% (1)

- Muhammad's Inspiration by JudaismDocument14 pagesMuhammad's Inspiration by JudaismCheradenine75% (4)

- History of The Waldenses. - William JonesDocument635 pagesHistory of The Waldenses. - William JonesPabloNo ratings yet

- Mohammedanism: Lectures on Its Origin, Its Religious and Political Growth, and Its Present StateFrom EverandMohammedanism: Lectures on Its Origin, Its Religious and Political Growth, and Its Present StateNo ratings yet

- Wright Jerusalem New TestamentDocument18 pagesWright Jerusalem New Testamentkkhipple100% (1)

- A Nineteenth Century Miracle, The Brothers Ratisbonne and The Congregation of Notre Dame de Sion (1922)Document374 pagesA Nineteenth Century Miracle, The Brothers Ratisbonne and The Congregation of Notre Dame de Sion (1922)luvpuppy_uk100% (1)

- The Crusades: Classic Histories Series: The War Against Islam 1096-1798From EverandThe Crusades: Classic Histories Series: The War Against Islam 1096-1798Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Apology of Al Kindy,: in Defence of Christianity Against IslamDocument122 pagesApology of Al Kindy,: in Defence of Christianity Against IslamShan SirajNo ratings yet

- Between Christ and Caliph: Law, Marriage, and Christian Community in Early IslamFrom EverandBetween Christ and Caliph: Law, Marriage, and Christian Community in Early IslamNo ratings yet

- The Hope of Catholick Judaism (1910) HartDocument184 pagesThe Hope of Catholick Judaism (1910) HartDavid BaileyNo ratings yet

- The Silesian Horseherd - Questions of the HourFrom EverandThe Silesian Horseherd - Questions of the HourNo ratings yet

- Al Kindy's Defense of Christianity Against IslamDocument122 pagesAl Kindy's Defense of Christianity Against IslamNjono SlametNo ratings yet

- Everyone Belongs to God: Discovering the Hidden ChristFrom EverandEveryone Belongs to God: Discovering the Hidden ChristRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Crusades - ThorauDocument11 pagesCrusades - ThorauAltafNo ratings yet

- The War with Russia; Its Origin and Cause: A Reply to the Letter of J. Bright, Esq., M.PFrom EverandThe War with Russia; Its Origin and Cause: A Reply to the Letter of J. Bright, Esq., M.PNo ratings yet

- The Silesian Horseherd - Questions of The Hour by Müller, F. Max (Friedrich Max), 1823-1900Document90 pagesThe Silesian Horseherd - Questions of The Hour by Müller, F. Max (Friedrich Max), 1823-1900Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The World's Great Sermons - Talmage to Knox Little - Volume VIIIFrom EverandThe World's Great Sermons - Talmage to Knox Little - Volume VIIINo ratings yet

- The Crusades - From Five Perspectives Christian Jewish and Muslim PDFDocument15 pagesThe Crusades - From Five Perspectives Christian Jewish and Muslim PDFLuiz Cesar MagalhaesNo ratings yet

- Faith of Islam QuilliamDocument88 pagesFaith of Islam QuilliamMohammad Hamid MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Komatsu Wheel Loader Wa900 8r Shop Manual Sen06750 04 2020Document22 pagesKomatsu Wheel Loader Wa900 8r Shop Manual Sen06750 04 2020brianwong090198pni100% (16)

- Bible in China BroomhallDocument209 pagesBible in China BroomhallYU JonahNo ratings yet

- The Dot On the I In History: Of Gentiles and Jews—a Hebrew Odyssey Scrolling the InternetFrom EverandThe Dot On the I In History: Of Gentiles and Jews—a Hebrew Odyssey Scrolling the InternetNo ratings yet

- Fulcher of Chartres ChronicleDocument74 pagesFulcher of Chartres ChronicleБелый Орёл100% (1)

- George Whitefield: A Biography, with special reference to his labors in AmericaFrom EverandGeorge Whitefield: A Biography, with special reference to his labors in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Mancipia March, 2007Document8 pagesMancipia March, 2007Saint Benedict Center100% (1)

- The Key to the Middle East: Discovering the Future of Israel in Biblical ProphecyFrom EverandThe Key to the Middle East: Discovering the Future of Israel in Biblical ProphecyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Acfrogcvrlus9a1t3x6zmw0p7lnvima Iauj Wsdsi6w6tl6 Yg7cu56lnresl6mmh1cio05-Pdsyylp9lg201bd-Is6lyo2qpuimlciuvj7d5u48jdyq9iarj52ypj11fcniyt86 Lzxv8q5ecvDocument8 pagesAcfrogcvrlus9a1t3x6zmw0p7lnvima Iauj Wsdsi6w6tl6 Yg7cu56lnresl6mmh1cio05-Pdsyylp9lg201bd-Is6lyo2qpuimlciuvj7d5u48jdyq9iarj52ypj11fcniyt86 Lzxv8q5ecvLeslianys Henriquez MaysonetNo ratings yet

- Christ and His Church: An Overview of the History of ChristianityFrom EverandChrist and His Church: An Overview of the History of ChristianityNo ratings yet

- Apology of Al Kindy,: Sir William Muir, K.C.S.I. Ll.D. D.C.L.Document121 pagesApology of Al Kindy,: Sir William Muir, K.C.S.I. Ll.D. D.C.L.vincent11abNo ratings yet

- The Second Wave of EvangelizationDocument10 pagesThe Second Wave of EvangelizationaleteiadocsNo ratings yet

- Allard. Ten Lectures On The Martyrs. 1907.Document388 pagesAllard. Ten Lectures On The Martyrs. 1907.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- The Great Revival of the Eighteenth Century: with a supplemental chapter on the revival in AmericaFrom EverandThe Great Revival of the Eighteenth Century: with a supplemental chapter on the revival in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Neophyte-JR-with-Komarov-2019-07-06Document10 pagesNeophyte-JR-with-Komarov-2019-07-06EMS CommerceNo ratings yet

- 5 Ad 500 CharlemegneDocument4 pages5 Ad 500 CharlemegneAnonymous HF5fT2Tw6YNo ratings yet

- Michael Servetus and IslamDocument17 pagesMichael Servetus and IslamCorneliusNo ratings yet

- The Church and the Barbarians: Being an Outline of the History of the Church from A.D. 461 to A.D. 1003From EverandThe Church and the Barbarians: Being an Outline of the History of the Church from A.D. 461 to A.D. 1003No ratings yet

- 40 Years in The Turkish EmpireDocument524 pages40 Years in The Turkish EmpireAlin DiaconuNo ratings yet

- Hourani 90Document65 pagesHourani 90plotinus2No ratings yet

- Product Description: The Pilgrim ChurchDocument4 pagesProduct Description: The Pilgrim ChurchrhokrizNo ratings yet

- Medieval Prophecy and Religious Dissent - Robert E. LernerDocument23 pagesMedieval Prophecy and Religious Dissent - Robert E. LernerSalva Rubio RealNo ratings yet

- Akenson - Surpassing Wonder The Invention of The Bible and The Talmuds (1998)Document672 pagesAkenson - Surpassing Wonder The Invention of The Bible and The Talmuds (1998)HansHeru100% (4)

- Quotation xr2021052 Xircon Malawi Liverpool TrustDocument1 pageQuotation xr2021052 Xircon Malawi Liverpool TrustBilquees SulemanNo ratings yet

- Schengen Visa Application FormDocument8 pagesSchengen Visa Application FormYasser Hammad MohamedNo ratings yet

- Tender Advert For The Distribution ProductsDocument3 pagesTender Advert For The Distribution ProductsBilquees SulemanNo ratings yet

- This Price List Will Be Effective From 1 June 2014. Single Station Bi-Axial Rotational Moulding Machines: EN SeriesDocument5 pagesThis Price List Will Be Effective From 1 June 2014. Single Station Bi-Axial Rotational Moulding Machines: EN SeriesBilquees SulemanNo ratings yet

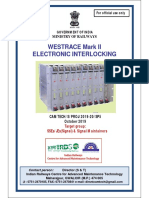

- WESTRACE Mark II EIDocument16 pagesWESTRACE Mark II EISampreeth Nambisan Perigini100% (2)

- Lifetime Warranty For The Autocom CDPDocument1 pageLifetime Warranty For The Autocom CDPApostol DorinNo ratings yet

- Pay and Benefits Information For Last Mile Health Employees Based in MalawiDocument2 pagesPay and Benefits Information For Last Mile Health Employees Based in MalawiBilquees SulemanNo ratings yet

- User Guide Ocsilloscope 1.4 EngDocument10 pagesUser Guide Ocsilloscope 1.4 EngApostol DorinNo ratings yet

- History of QuranDocument71 pagesHistory of QuranSarbu AnaNo ratings yet

- Paul Starkey Modern Arabic Literature New Edinburgh Islamic Surveys S. 2006Document233 pagesPaul Starkey Modern Arabic Literature New Edinburgh Islamic Surveys S. 2006Claudia Varela100% (1)

- Younes Alaoui Shajarat Al-Kawn Critical StudyDocument16 pagesYounes Alaoui Shajarat Al-Kawn Critical StudySi DiNo ratings yet

- A Shī Ī-Jewish Debate (Munā Ara) in The Eighteenth CenturyDocument21 pagesA Shī Ī-Jewish Debate (Munā Ara) in The Eighteenth CenturyJaffer AbbasNo ratings yet

- Kalki Avtar in Hinduism Prophet Mohammed (Pbuh) - A Research by Hindu PunditDocument4 pagesKalki Avtar in Hinduism Prophet Mohammed (Pbuh) - A Research by Hindu Punditismailp99626275% (8)

- Introduction To Islamic Creed v4 PDFDocument102 pagesIntroduction To Islamic Creed v4 PDFAzeez MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Bruce Chatwin's insights on human restlessness and the need for movementDocument4 pagesBruce Chatwin's insights on human restlessness and the need for movementDámaris HernándezNo ratings yet

- The Flowing TearDocument457 pagesThe Flowing Tearroukayakazan81No ratings yet

- 40 HadithsDocument104 pages40 HadithsPaeghamNo ratings yet

- Islamic Sainthood in The Fullness of Time by Gerald T. ElmoreDocument785 pagesIslamic Sainthood in The Fullness of Time by Gerald T. ElmoreSY Lodhi100% (2)

- Unraveling Islam 2016 Q4Document134 pagesUnraveling Islam 2016 Q4isa.koran5628No ratings yet

- Qawaid Al-Aqaid - English - Al-GhazaliDocument150 pagesQawaid Al-Aqaid - English - Al-GhazaliJohn100% (3)

- The Holy Quran Malayalam Translation of MeaningDocument904 pagesThe Holy Quran Malayalam Translation of MeaningArshad Farooqui100% (14)

- IstighosahDocument4 pagesIstighosahRizal MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Feb 4Document17 pagesFeb 4api-266327898No ratings yet

- Tariqah Muammadiyyah As Tariqah Jami ADocument36 pagesTariqah Muammadiyyah As Tariqah Jami AUzairNo ratings yet

- زيادات موطأ محمد بن الحسن الشيباني عن موطأ يحي بن يحي الليثي ومميزاتها PDFDocument17 pagesزيادات موطأ محمد بن الحسن الشيباني عن موطأ يحي بن يحي الليثي ومميزاتها PDFعبدالله بن هيمان المصرىNo ratings yet

- IRE 1 GuideDocument17 pagesIRE 1 GuideMAFABI BURUHANNo ratings yet

- Excerpts From Mikyalul MakarimDocument113 pagesExcerpts From Mikyalul MakarimawaitingNo ratings yet

- GeomancyDocument159 pagesGeomancyalimuhammedkhan211550% (2)

- 2.2khutbah Bandingan Ko Kaphiapiai Ko Mbala A LoksDocument4 pages2.2khutbah Bandingan Ko Kaphiapiai Ko Mbala A LoksJohari AbubacarNo ratings yet

- Jihad: From Muhammad To ISIS (Post Hill Press, Nashville/New York, 2018) and DedicatedDocument9 pagesJihad: From Muhammad To ISIS (Post Hill Press, Nashville/New York, 2018) and DedicatedSaptarshi BasuNo ratings yet

- Death and TaqwaDocument10 pagesDeath and TaqwaTruthful MindNo ratings yet

- Islamiyat O'Level Notes - Life and Importance of Prophet MuhammadDocument9 pagesIslamiyat O'Level Notes - Life and Importance of Prophet MuhammadAmeer100% (1)

- Diverse Community: Learning From Each OtherDocument7 pagesDiverse Community: Learning From Each OtherabdoullahNo ratings yet

- Salawats On Sayyidina RasulullahDocument18 pagesSalawats On Sayyidina Rasulullahzarlakhta100% (3)

- The KoranDocument4 pagesThe KorankiminNo ratings yet

- The Four KhalifahDocument4 pagesThe Four KhalifahShabbir AhmadNo ratings yet

- Irshadut TalibeenDocument28 pagesIrshadut Talibeenmraihana.100No ratings yet

- An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sFrom EverandAn Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (19)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesFrom EverandSon of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (496)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Becky Lynch: The Man: Not Your Average Average GirlFrom EverandBecky Lynch: The Man: Not Your Average Average GirlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Broken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.From EverandBroken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (43)

- If I Did It: Confessions of the KillerFrom EverandIf I Did It: Confessions of the KillerRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (132)