Professional Documents

Culture Documents

11 Hypermobility Syndrome

Uploaded by

Yan Zhen YuanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

11 Hypermobility Syndrome

Uploaded by

Yan Zhen YuanCopyright:

Available Formats

ARTICLE

Hypermobility Syndrome

David B. Everman, MD* and Nathaniel H. Robin, MD*†

ing late childhood or early adoles-

IMPORTANT POINTS cence and more slowly through

1. Generalized joint hypermobility is a common clinical finding; adulthood. The age-related decline

its prevalence varies with age, gender, and ethnicity. in joint mobility has been attributed

2. Screening for the presence of generalized hypermobility is accom- to progressive biochemical changes

plished easily and rapidly by using five clinical maneuvers and in collagen structure that result in

the Beighton scoring system. stiffening of the connective tissue

3. Hypermobility syndrome should be considered in the differential components of joints. At any given

diagnosis of children who have musculoskeletal complaints. age, females have a greater degree

4. Hypermobility syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, and the finding of joint laxity. Hypermobility also

of generalized hypermobility on physical examination should prompt varies dramatically among ethnic

consideration of serious disorders of connective tissue. groups, occurring more commonly

5. Treatment of hypermobility syndrome includes nonsteroidal anti- in persons of African, Asian, and

inflammatory drug administration and counseling about the benign Middle Eastern descent. Within

nature of the condition and the relationship of symptoms to joint

these ethnic groups, the pattern of

activity.

age- and gender-related variation

is maintained.

Researchers investigating the

prevalence of hypermobility syn-

Definitions Hypermobility syndrome is the drome often have examined patients

Hypermobility is defined as an term used to describe otherwise in rheumatology clinics, where they

abnormally increased range of joint healthy individuals who exhibit gen- are referred for evaluation of muscu-

motion due to excessive laxity of the eralized hypermobility associated loskeletal complaints. Systematic

constraining soft tissues. Although it with musculoskeletal complaints. examination of these individuals

usually is a benign clinical finding The term was coined in 1967 by for evidence of generalized hyper-

that has few serious implications, Kirk and colleagues, who reported mobility in the absence of systemic

it should raise the clinician’s level the occurrence of rheumatic symp- disease has yielded prevalence fig-

of concern for the presence of an toms in a group of hypermobile chil- ures for hypermobility syndrome of

underlying disorder, particularly one dren who had no connective tissue 2% to 5%, with a relative predomi-

involving the connective tissue. In disorders or other forms of systemic nance of young girls. As with gener-

addition, its association with joint disease. Some clinicians prefer the alized hypermobility, these figures

symptoms makes hypermobility term benign joint hypermobility probably underestimate the true

an important clinical finding in syndrome to distinguish affected prevalence of the syndrome because

children who have musculoskeletal individuals from those manifesting many individuals do not seek med-

complaints. hypermobility as part of a more seri- ical evaluation for mild and inter-

In theory, the distinction between ous disorder. Because hypermobility mittent musculoskeletal symptoms.

hypermobility and the upper limit of syndrome has a strong genetic com- In the subset of patients who have

normal mobility is arbitrary because ponent, it also has been called famil- episodic and unexplained joint pain,

joint motion varies within the gen- ial joint hypermobility. the prevalence of hypermobility syn-

eral population. In practice, how- drome may be significantly higher.

ever, it is not difficult to distinguish Gedalia and colleagues found gener-

hypermobility from the generally Epidemiology and Etiology alized hypermobility in 66% of

accepted clinical norm in the major- Generalized hypermobility in the school children who had recurrent

ity of children. Hypermobility may absence of systemic disease is a arthritis or arthralgia of unknown

be localized, involving one or sev- common condition that has a preva- etiology. Although arthritis usually

eral joints, or generalized, involving lence of 4% to 13% in the general is not considered a feature of hyper-

a number of joints throughout the population. This probably is an mobility syndrome, these data sug-

body. Although excessive joint laxity underestimate of the true frequency gest an increased prevalence of this

is a prominent feature of many because many people who have condition in children who present

systemic disorders, it occurs more hypermobility do not develop joint with intermittent musculoskeletal

commonly in isolation. symptoms or seek medical attention. complaints.

Moreover, the prevalence of hyper- The primary conditions that can

mobility varies markedly with age, involve hypermobility are listed in

*Center for Human Genetics, Department of

Genetics.

gender, and ethnicity of the study Table 1. Generalized hypermobility

†Department of Pediatrics, Case Western

population. It is well known that is a prominent feature of hereditary

Reserve University School of Medicine, children have relatively loose joints connective tissue disorders, includ-

University Hospitals of Cleveland, compared with adults; this normal ing Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos

Cleveland, OH. joint laxity diminishes rapidly dur- syndrome, and osteogenesis imper-

Pediatrics in Review Vol. 19 No. 4 April 1998 111

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

MUSCULOSKELETAL

Hypermobility

Familial asymptomatic hypermobil-

TABLE 1. Select Conditions Featuring Hypermobility ity is a term used to describe contor-

tionists, who demonstrate significant

• Hypermobility syndrome

generalized joint laxity but do not

• Hereditary connective tissue disorders develop joint symptoms. Finally, it

— Marfan syndrome is important to distinguish true joint

— Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility from apparent hyper-

— Osteogenesis imperfecta mobility, which occurs in the con-

— Marfanoid hypermobility syndrome text of muscular hypotonia.

— Williams syndrome Although the precise etiology of

— Stickler syndrome hypermobility syndrome is unknown,

• Chromosome disorders it clearly has a strong genetic com-

— Down syndrome ponent. Affected first-degree rela-

— Killian/Teschler-Nicola syndrome tives are identified in as many as

50% of cases. An autosomal domi-

• Other genetic syndromes nant pattern of inheritance is most

— Autosomal dominant common, although autosomal reces-

– Velo-cardio-facial syndrome sive and X-linked transmission also

– Hajdu-Cheney syndrome have been documented.

– Pseudoachondroplastic spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia The predominance of affected

– Myotonia congenita females who have hypermobility

— Autosomal recessive

syndrome has fueled speculation

– Cohen syndrome

about the role of gender-related

— Heterogeneous (autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive)

factors in the development and

– Larsen syndrome

expression of the condition. Some

– Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

— X-linked dominant clinicians have observed phenotypic

– Coffin-Lowry syndrome differences, including variations in

— Sporadic location, nature, and severity of joint

– Goltz syndrome symptoms, between affected males

and females from the same family.

• Metabolic disorders The relative contribution of environ-

— Homocystinuria mental influences, such as estrogen,

— Hyperlysinemia or X-linked genetic factors is not

• Orthopedic conditions understood.

— Congenital hip dysplasia

— Recurrent dislocation of shoulder

— Recurrent dislocation of patella Pathogenesis

— Clubfoot There are questions about whether

• Acquired diseases hypermobility syndrome represents

— Neurologic the upper end of normal variation in

– Polio joint mobility or it reflects a mild

– Tabes dorsalis disorder of connective tissue. In

— Rheumatologic support of the latter view, stigmata

– Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis of generalized connective tissue

– Rheumatic fever involvement, including marfanoid

• Familial asymptomatic hypermobility (contortionists) habitus, high-arched palate, skin

striae, hyperelastic or thin skin, vari-

• Apparent hypermobility (muscular hypotonia) cose veins, and spinal abnormalities,

have been observed in some patients

who have hypermobility syndrome.

fecta. In the marfanoid hypermobil- and sporadic genetic syndromes. Additional studies have documented

ity syndrome, generalized hypermo- Joint laxity may be associated with an increased incidence of mitral

bility is present in combination with orthopedic abnormalities, including valve prolapse in hypermobile indi-

the typical skeletal manifestations congenital hip dysplasia and recur- viduals, but this association has

and skin hyperelasticity of Marfan rent dislocations of the shoulder been controversial.

syndrome, but the ocular and cardio- and patella. Hypermobility may be Biochemical and molecular

vascular manifestations are absent. acquired in neurologic conditions, research has supported the classifi-

Hypermobility often is found in such as polio and tabes dorsalis, and cation of hypermobility syndrome as

metabolic diseases such as homo- in rheumatologic diseases. Although a connective tissue disorder. Colla-

cystinuria and hyperlysinemia, chro- hypermobility can develop in juve- gen analysis of skin samples from

mosomal disorders such as Down nile rheumatoid arthritis, limitation patients who have hypermobility

syndrome, and a variety of familial of joint motion is much more likely. syndrome has demonstrated alter-

112 Pediatrics in Review Vol. 19 No. 4 April 1998

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

MUSCULOSKELETAL

Hypermobility

ations in the normal ratios of colla- ized in one or several joints or it nective tissue disorders. Such find-

gen subtypes and abnormalities of may be generalized and symmetric. ings can include pes planus, scolio-

the microscopic connective tissue Although pain most commonly sis, lordosis, genu valgum, lateral

structure. In 1996, the British involves the knee, any joint, includ- patellar displacement, marfanoid

Society for Rheumatology reported ing those of the spine, can be habitus, high-arched palate, skin

the identification of mutations in affected. The pain usually is self- striae, thin skin, and varicose veins.

fibrillin genes in several families limited in duration, but it can recur Although most affected children

who had hypermobility syndrome. with activity. Less commonly, chil- do not have cardiovascular findings,

Despite intensive speculation, the dren may experience joint stiffness, a subset of patients may have evi-

pathogenesis of generalized joint myalgias, muscle cramps, and dence of mitral valve prolapse

laxity in hypermobility syndrome nonarticular limb pain. Although (MVP). As noted previously, the

remains unclear. It appears likely brief episodes of joint swelling can association of MVP with hyper-

that normal joint development and occur in hypermobility syndrome, mobility syndrome is controversial.

function require the interaction of they are uncommon and should Although early studies indicated an

a number of genes coding for the prompt consideration of an alterna- increased incidence of MVP in

structure and assembly of joint- tive diagnosis. In some cases, the affected patients, more recent inves-

related connective tissue proteins. onset of symptoms is preceded by tigations that used stricter echocar-

Although hypermobility syndrome a recent growth spurt, and affected diographic criteria for the diagnosis

may result from one or more muta- females often report premenstrual of MVP have questioned this associ-

tions in such genes, the importance exacerbations. Because symptoms ation. However, serious cardiovascu-

of pathogenetic classification is a typically are related to activity, they lar abnormalities are seen with some

problem of semantics rather than tend to occur later in the day. In connective tissue disorders that also

a clinically relevant issue for the contrast to arthritic disorders, morn- manifest hypermobility. For this

general pediatrician. ing stiffness is an uncommon find- reason, any hypermobile child who

The pathogenesis of joint com- ing in children who have hypermo- has suspicious cardiac symptoms or

plaints in patients who have hyper- bility syndrome. Instead, they may physical findings requires further

mobility syndrome may be under- awaken at night with complaints of

evaluation by a cardiologist.

stood best by considering the basic joint or extremity pain, especially

structure of a joint. The extent of following an active day. Frequently,

joint mobility is determined by the affected children will have a family

history of similar complaints or Diagnosis

strength and flexibility of surround-

ing soft tissues, including the joint “double-jointedness” in childhood The key to making the diagnosis

capsule, ligaments, tendons, mus- among first-degree relatives. In of hypermobility syndrome lies in

cles, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. addition to relatively nonspecific accurate assessment of the child for

It has been hypothesized that exces- musculoskeletal complaints, some evidence of generalized joint laxity.

sive joint laxity leads to inappropri- patients may have an associated This is accomplished with five sim-

ate wear and tear on joint surfaces history of congenital hip dysplasia, ple clinical maneuvers that require

and surrounding soft tissues, result- recurrent joint dislocations or no special equipment and can be

ing in symptoms referable to these subluxations, ligament or tendon performed by any general physician

tissues. The clinical observation rupture, easy bruising, fibromy- in 30 to 60 seconds (Figs. 1–5). The

of increased symptoms related to algia, or temporomandibular joint father of the 3-year-old girl shown

excessive use of hypermobile joints dysfunction. in the figures is similarly affected,

lends further support to this hypoth- In addition to the primary finding illustrating that hypermobility syn-

esis. Recent studies also have demon- of generalized joint hypermobility, drome can be seen at any age. It

strated reduced proprioceptive sen- physical examination may reveal should be noted that joint laxity in

sation in the joints of patients who pain upon joint manipu-

have hypermobility syndrome. Such lation and, in unusual

findings have led to speculation that cases, mild degrees of

effusion. Signs of active

impaired sensory feedback con-

inflammation, including

tributes to excessive joint trauma

significant tenderness,

in affected individuals.

swelling, redness,

warmth, and fever, are

absent. If such findings

Clinical Manifestations are present, they sug-

Children who have hypermobility gest another diagnosis.

syndrome may present with a vari- Examination of

ety of musculoskeletal complaints. patients who have

The most common symptom is joint hypermobility syn-

pain, which often develops after drome also may reveal

physical activities or sports during extra-articular abnor- FIGURE 1. Assessing generalized joint laxity: passive

which the affected joint(s) is/are malities that are more apposition of the thumb to the flexor surface of the

used repeatedly. Pain may be local- typical of serious con- forearm.

Pediatrics in Review Vol. 19 No. 4 April 1998 113

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

MUSCULOSKELETAL

Hypermobility

FIGURE 2. Assessing generalized joint laxity: passive dorsi- FIGURE 3. Assessing generalized joint laxity: hyperextension

flexion of the fifth finger beyond 90 degrees (in parallel to the of the elbow beyond 10 degrees.

extensor surface of the forearm).

toms, a number of less

commonly associated

features have been

incorporated into these

criteria.

Although hyper-

mobility syndrome is a

relatively common con-

dition, it is a diagnosis

of exclusion. Exclusion

of more serious infec-

tious, inflammatory, and

autoimmune disorders

presenting with painful

or swollen joints can

be aided by appropriate

laboratory studies,

including complete

blood count, erythro-

cyte sedimentation rate

(ESR), rheumatoid

FIGURE 4. Assessing generalized joint FIGURE 5. Assessing generalized joint laxity: forward factor, antinuclear anti-

laxity: hyperextension of the knee flexion of the trunk, with the knees held straight, such body (ANA) titer, and

beyond 10 degrees. that the palms of the hands rest flat on the floor.

levels of serum immune

globulin and comple-

patients who have hypermobility Patients are scored on a 9-point ment. Such tests usually are not

syndrome is virtually always sym- scale, with 1 point awarded for indicated in children who have

metric, except in the presence of each hypermobile site. The points hypermobility syndrome, and results

other musculoskeletal abnormalities then are summed to give a total are normal when the tests are per-

that might limit joint motion. In or “Beighton score” (Fig. 6). A formed. Abnormalities in any of

addition, some consider hyperexten- Beighton score of 4 or more points these tests, such as leukocytosis,

sion of all fingers, not just the fifth usually is considered indicative increased ESR, or a positive ANA

finger, as the physical finding to of generalized hypermobility. titer, suggest an alternative diagno-

examine in hypermobility syndrome. Because there is considerable sis. If there is joint effusion, aspira-

Developed by Carter and Wilkin- clinical overlap between hypermo- tion of the joint fluid will reveal a

son and later modified by Beighton bility syndrome and heritable dis- noninflammatory pattern in patients

for large population studies, this orders of connective tissue, specific who have hypermobility syndrome.

examination has become the most diagnostic criteria have been devel-

widely accepted screen for detecting oped by the British Society for

generalized hypermobility. It corre- Rheumatology (Table 2). In addition Differential Diagnosis

lates well with more quantitative, to findings of generalized hyper- As outlined in Table 1, the differ-

instrument-dependent methods. mobility and musculoskeletal symp- ential diagnosis of hypermobility

114 Pediatrics in Review Vol. 19 No. 4 April 1998

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

MUSCULOSKELETAL

Hypermobility

connective tissue disease. For these

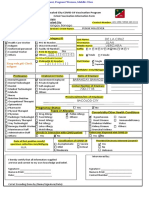

UNABLE TO ABLE TO reasons, it is critical for the clinician

PERFORM PERFORM

CLINICAL MANEUVER (0 POINTS) (1 POINT)

to recognize the distinguishing fea-

tures of inherited connective tissue

Apposition of thumb to forearm disorders in hypermobile children.

Right 0 1

Left 0 1

EHLERS-DANLOS SYNDROME

Extension of fifth finger beyond 90 degrees Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS)

Right 0 1 refers to a group of connective

Left 0 1

tissue disorders that shares the fea-

Extension of elbow beyond 10 degrees tures of joint hypermobility and

Right 0 1 skin abnormalities. The skin find-

Left 0 1 ings may range from softness, thin-

Extension of knee beyond 10 degrees ness, or hyperelasticity to extreme

Right 0 1 fragility with easy bruisability and

Left 0 1 abnormal scar formation. There are

ten subtypes of EDS, which differ

Forward flexion of trunk, legs straight,

palms touching floor 0 1

in terms of severity of joint and

skin findings, involvement of other

Total Beighton Score (sum of points 0 to 9 points tissues, and mode of inheritance.

for each maneuver) Specific molecular defects in colla-

gen or enzymes involved in connec-

FIGURE 6. Calculation of the Beighton score. tive tissue formation have been

identified in several EDS subtypes.

TABLE 2. Proposed Criteria for Hypermobility Syndrome The majority of EDS cases are

represented by types I, II, and III.

Major Criteria The most severe joint laxity is seen

1. A Beighton score of 4 out of 9 or greater (either currently or in EDS type I; affected patients

historically). have significant hypermobility, often

2. Arthralgia for longer than 3 months in four or more joints. accompanied by pain, effusion, and

dislocation. Children who have this

Minor Criteria

condition may experience congenital

1. A Beighton score of 1, 2, or 3 out of 9 (0, 1, 2, or 3 if age is 50+)

hip dislocation, clubfeet, or delayed

2. Arthralgia in one to three joints or back pain or spondylosis,

ambulation due to joint symptoms

spondylolysis/olisthesis.

and leg instability. Associated skin

3. Dislocation in more than one joint or in one joint on more than

one occasion. findings include soft, extensible skin

4. Three or more soft tissue lesions (eg, epicondylitis, tenosynovitis, with a velvety texture, easy bruising,

bursitis). and formation of thin “cigarette

5. Marfanoid habitus (tall, slim, span greater than height, ratio of upper paper” scars when injured. EDS

segment to lower segment <0.89, arachnodactyly). type II is similar to but less severe

6. Skin: striae, hyperextensibility, thin skin, or abnormal scarring. than EDS type I. Both disorders are

7. Eye signs: drooping eyelids, myopia, or antimongoloid slant. caused by defects in type V collagen

8. Varicose vein, hernia, or uterine/rectal prolapse. and inherited in an autosomal domi-

9. Mitral valve prolapse (by echocardiography). nant fashion. Autosomal recessive

cases of EDS type II, caused by

The hypermobility syndrome is diagnosed in the presence of two major or other collagen defects, have been

one major and two minor or four minor criteria. Two minor will suffice reported but are rare. EDS type III

where there is an unequivocally affected first-degree relative. Hypermobil- is similar to type I with respect to

ity syndrome is excluded by the presence of Marfan syndrome or Ehlers- joint involvement, but skin abnor-

Danlos syndrome as defined by the Berlin Nosology. malities usually are limited to an

From: Bird HA. Joint hypermobility: reports from Special Interest Groups of the annual abnormally soft and velvety texture.

meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31:205–208. For this reason, EDS type III often

Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press. is confused with hypermobility syn-

drome, which generally is believed

to have few or no skin changes.

includes a wide variety of genetic serious disorders of connective From a practical standpoint, how-

and acquired disorders, and it is tissue is a particularly common ever, the clinical differences are min-

important to consider each of these diagnostic dilemma. Further, imal, and the two disorders should

possibilities when evaluating a asymptomatic hypermobility may be managed similarly. EDS type

patient who presents with general- be detected frequently on routine III is transmitted in an autosomal

ized joint laxity. Differentiating physical examination, prompting dominant fashion, and the precise

hypermobility syndrome from more the possibility of an undiagnosed molecular defect is unknown.

Pediatrics in Review Vol. 19 No. 4 April 1998 115

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

MUSCULOSKELETAL

Hypermobility

Of the less frequent subtypes of fragility, often resulting in multiple Management

EDS, the most important to recog- fractures and bony deformities. After more serious disorders are

nize is EDS type IV. Although joint The disorder is highly variable, excluded and hypermobility syn-

and skin abnormalities are usually frequently arises from a sporadic drome is diagnosed, clinical man-

mild, affected individuals have a mutation, and includes both lethal agement is straightforward. First

markedly increased risk of poten- and nonlethal forms. Lethal forms and foremost, the child and his or

tially fatal spontaneous rupture of involve severe bone fragility that her family should be reassured that

the arteries and hollow organs, such is incompatible with life. The non- hypermobility syndrome is a rela-

as the colon. Women who have EDS lethal varieties may be more subtle tively common and benign condition

type IV may experience uterine rup- in clinical presentation, with com- that does not have the potentially

ture during pregnancy. This autoso- plications related to fractures, joint disabling or life-threatening sequelae

mal dominant disorder is caused by instability, short stature, and pro- of other rheumatologic or connective

defective type III collagen. Of note, gressive spinal deformity. The latter tissue disorders. Such reassurance

a revised EDS clinical classification problem may lead to cardiorespira- may prove particularly helpful to

system has been proposed. tory compromise, and effective sur- the parents of children who have a

gical correction is difficult because history of nonspecific and recurrent

MARFAN SYNDROME of bone fragility. In adulthood, pro- musculoskeletal complaints.

Marfan syndrome is an autosomal gressive otosclerosis often results For acute symptoms, patients

dominant disorder characterized by in deafness. should be advised to use non-

a tall, thin body habitus (marfanoid steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

habitus), long extremities, elongated STICKLER SYNDROME (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen as

fingers (arachnodactyly), ocular Stickler syndrome is an autosomal needed. A bedtime dose of a longer

abnormalities (myopia, lens dislo- dominant disorder that is character- acting NSAID, such as naproxen,

cation), and generalized joint hyper- ized by hypermobility, typical facial may benefit children who have

mobility. It is caused by mutations features (malar hypoplasia with nocturnal symptoms. Because the

in the fibrillin-1 gene on chromo- depressed nasal bridge and epican- pathogenesis of joint complaints in

some 15. Fibrillin is an essential thal folds), Robin sequence (micro- hypermobility syndrome is not

glycoprotein component of elastic gnathia, glossoptosis, and cleft related to inflammation, the effec-

connective tissue. Recognition of palate), early-onset arthritis, severe tiveness of NSAIDs for symptoms

this disorder is critical because myopia, and sensorineural hearing other than pain has been disputed.

patients are predisposed to life- loss. Affected infants often experi- Moderate or severe symptoms may

threatening aneurysms and dissec- ence respiratory problems related necessitate rest or abstention from

tions of the aorta as well as aortic to Robin sequence, and children activities that aggravate joint com-

valve regurgitation and mitral valve may develop arthritis before ado- plaints. Physical therapy and hydro-

prolapse. Because of the serious lescence. Severe myopia and an therapy can provide additional relief

nature of Marfan syndrome, any increased risk of retinal detachment of acute symptoms.

child suspected of having this necessitate frequent ophthalmologic Chronic management of this con-

condition should undergo genetic, evaluation. dition typically involves several

cardiologic, and ophthalmologic strategies, including explanation

evaluation. As part of this evalua- WILLIAMS SYNDROME of the nature of hypermobility syn-

tion, plasma amino acids should be Williams syndrome is another auto- drome and the association between

analyzed to exclude the presence of somal dominant disorder featuring excessive joint movement and devel-

homocystinuria, a metabolic disorder hypermobility. However, joint laxity opment of symptoms. Patients

in which there is excessive accumu- is observed primarily in childhood; should be advised to identify activi-

lation of homocystine. In most older affected individuals may ties that precipitate symptoms and to

cases, this results from deficient develop joint contractures. These modify their lifestyles accordingly.

activity of the enzyme cystathionine patients also manifest short stature, Vigorous and repetitive activities, as

synthetase. Clinically, homocystin- characteristic facial appearance, performed during certain sports or

uria is very similar to Marfan syn- hoarse voice, developmental delay hobbies, may underlie the symptoms

drome with respect to body habitus, with an outgoing “cocktail party” and should be targeted as potential

lens dislocation, and generalized personality, and occasional hyper- aggravating factors. The use of

joint hypermobility. However, calcemia. Patients may have con- NSAIDs or acetaminophen prior to

patients who have homocystinuria genital cardiovascular disease, most such activities can help to control

may have mental retardation and commonly supravalvular aortic associated symptoms and facilitate

are at significantly increased risk stenosis, and are predisposed to participation. In some cases, affected

of arterial thrombosis. develop other vascular stenoses. children may require a physician’s

Recently, this syndrome has been excuse to avoid exacerbating symp-

OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA found to arise from deletions in the toms during physical education

Osteogenesis imperfecta, an autoso- long arm of chromosome 7, which classes at school.

mal dominant disorder of collagen, always includes the region of the Despite the importance of avoid-

is characterized by thin blue sclerae, elastin gene. Definitive diagnosis ing excessive activity, a diagnosis of

excessive joint mobility, and bone is possible by molecular testing. hypermobility syndrome should not

116 Pediatrics in Review Vol. 19 No. 4 April 1998

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

MUSCULOSKELETAL

Hypermobility

be used to encourage inactivity. experience fewer symptoms follow- SUGGESTED READING

Rather, it is generally accepted that ing menopause. Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B,

moderate exercise is extremely Although hypermobility syndrome Tsipouras P, Wenstrup RJ. Ehlers-Danlos

is a relatively benign condition, syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche,

beneficial by maximizing muscle 1997. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61(suppl):

support around hypermobile joints. some potentially significant sequelae A49

Swimming is advocated for improv- have been reported to occur with Beighton P, Solomon L, Soskolne CL. Articu-

ing general muscle tone, and spe- increased frequency in affected lar mobility in an African population.

patients. Studies of hypermobile Ann Rheum Dis. 1973;32:413–418

cific strengthening exercises may Bird HA. Joint hypermobility: reports from

help to increase muscular support football players and ballet dancers Special Interest Groups of the annual

in particularly symptomatic areas. have noted an increased frequency meeting of the British Society for Rheuma-

Because the knee is the joint of ruptured ligaments, joint disloca- tology. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31:205–208

tions, and other orthopedic injuries. Biro F, Gewanter HL, Baum J. The hyper-

involved most commonly, quadri- mobility syndrome. Pediatrics. 1983;72:

ceps exercises can be especially Affected individuals may be predis- 701–706

helpful. Instruction of children in posed to fractures, and scoliosis Carter C, Wilkinson J. Persistent joint laxity

joint protection techniques also may result from hypermobility of and congenital dislocation of the hip.

the spine. Some clinicians have J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46B:40–45

may prove beneficial. For example, Gedalia A, Brewer EJ. Joint hypermobility in

children who have hyperextensible observed hernias as well as uterine pediatric practice—a review. J Rheumatol.

and rectal prolapse with increased 1993;20:371–374

knees are encouraged to stand with

frequency in adults who have hyper- Gedalia A, Person DA, Brewer EJ, Giannini

their knees slightly flexed, while EH. Hypermobility of the joints in juvenile

mobility syndrome.

those who have unstable ankles episodic arthritis/arthralgia. J Pediatr. 1985;

Finally, it has been speculated

may benefit from the use of an ankle 107:873–876

that children who have hypermobil- Hall MG, Ferrell WR, Sturrock RD, Hamblen

aircast. Finally, patients who have ity syndrome are at increased risk of DL, Baxendale RH. The effect of the hyper-

significant symptoms or extreme developing premature degenerative mobility syndrome on knee joint proprio-

degrees of joint hypermobility osteoarthritis as adults. A specific ception. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:121–125

should be encouraged to avoid all Handler CE, Child A, Light ND, Dorrance

pattern of progression that involves DE. Mitral valve prolapse, aortic com-

sports, hobbies, or careers involving onset of osteoarthritis in the fourth pliance, and skin collagen in joint hyper-

physical activities that may result in to fifth decade, followed by eventual mobility syndrome. Br Heart J. 1985;54:

chronic and excessive joint stress. chondrocalcinosis within affected 501–508

Kirk JA, Ansell BM, Bywaters EGL. The

joints, has been described by some hypermobility syndrome: musculoskeletal

clinicians. However, much of the complaints associated with generalized

Prognosis evidence for this association has hypermobility. Ann Rheum Dis. 1967;26:

Because joints tend to stiffen with been anecdotal, and it remains an 419–425

age, the natural history of hypermo- Mishra MB, Ryan P, Atkinson P, et al. Extra-

issue of considerable debate. It articular features of benign joint hyper-

bility syndrome is typically one of generally is agreed that only long- mobility syndrome. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;

improvement, with progressively term prospective studies of patients 35:861–866

lessening degrees of joint laxity and who have hypermobility syndrome Morgan AW. Report on the Hypermobility

associated musculoskeletal symp- will provide the needed insight into Special Interest Group. Br J Rheumatol.

1996;35:392–393

toms. Many affected children out- the natural history and prognosis of Raff ML, Byers PH. Joint hypermobility

grow their symptoms during adoles- this common and often unrecognized syndromes. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;

cence or adulthood, and women may condition. 8:459–466

PIR QUIZ

1. Which of the following statements 2. An 8-year-old boy is brought to you 3. Which of the following is the most

regarding hypermobility is true? for pain in the knees and legs. Which appropriate management of a child

A. Caucasian children exhibit greater of the following favors the diagnosis who has hypermobility syndrome?

joint mobility than those of of hypermobility syndrome? A. Genetic counseling.

African descent. A. A grade II/VI diastolic murmur is B. Periodic echocardiographic

B. Hypermobility is a significant risk heard in the second left intercostal evaluation.

factor for mitral valve prolapse. space. C. Reassurance of its benign nature.

C. Joint laxity observed in early B. After evening soccer practices, D. Slitlamp examination of eyes.

childhood usually diminishes the patient is awakened with pain E. Urine amino acid analysis.

during late childhood and early at nights.

adolescence. C. Episodes of joint pain are associ- 4. Which of the following conditions

D. Males have a greater degree ated with low-grade fever. is associated with dislocated lens?

of joint laxity compared with D. A moderate amount of joint effu- A. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

females. sion without tenderness is noted B. Homocystinuria.

E. The presence of hypermobility is in both knee joints. C. Hypermobility syndrome.

usually indicative of a serious E. Point tenderness is observed on D. Osteogenesis imperfecta.

underlying connective tissue the medial aspect of both knees. E. Williams syndrome.

disorder.

Pediatrics in Review Vol. 19 No. 4 April 1998 117

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

Hypermobility Syndrome

David B. Everman and Nathaniel H. Robin

Pediatrics in Review 1998;19;111

DOI: 10.1542/pir.19-4-111

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/19/4/111

References This article cites 12 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/19/4/111.full#ref-list-1

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the following

collection(s):

Rheumatology/Musculoskeletal Disorders

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/rheumatology:musculo

skeletal_disorders_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or in its entirety

can be found online at:

https://shop.aap.org/licensing-permissions/

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/reprints

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

Hypermobility Syndrome

David B. Everman and Nathaniel H. Robin

Pediatrics in Review 1998;19;111

DOI: 10.1542/pir.19-4-111

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the

World Wide Web at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/19/4/111

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it has

been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned, published, and trademarked by the

American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 1998 by the American

Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0191-9601.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Philippines:AAP Sponsored on October 3, 2019

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- CPG AID - Full VersionDocument120 pagesCPG AID - Full VersionJoniee SnowNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- How To Make Liquid Doxy 2007Document2 pagesHow To Make Liquid Doxy 2007Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- DOH National Antibiotic Guidelines 2017Document264 pagesDOH National Antibiotic Guidelines 2017Degee O. Gonzales67% (3)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- CPN-CSPC Protocol 26nov2014Document136 pagesCPN-CSPC Protocol 26nov2014John J. MacasioNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- 14 Nice Uti 2018Document23 pages14 Nice Uti 2018Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Guarino 2014Document21 pagesGuarino 2014ChangNo ratings yet

- CPG AID - Full VersionDocument120 pagesCPG AID - Full VersionJoniee SnowNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Doxycycline: in An EmergencyDocument2 pagesDoxycycline: in An EmergencyYan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- IDSA Guidelines On The Treatment of MRSA InfectionsDocument5 pagesIDSA Guidelines On The Treatment of MRSA Infectionsbenny christantoNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Consensus Guidelines For The Management of Atopic Dermatitis - An Asia Pacific Perspective PDFDocument12 pagesConsensus Guidelines For The Management of Atopic Dermatitis - An Asia Pacific Perspective PDFRatna U LukitaningtyasNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- 2017 AHA Kawasaki DiseaseDocument74 pages2017 AHA Kawasaki DiseaseEdwin WijayaNo ratings yet

- Isk - AapDocument14 pagesIsk - AapRoberto SoehartonoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 14 AAP Salmonella Infections 2019Document5 pages14 AAP Salmonella Infections 2019Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- PIIS0002934317302206Document8 pagesPIIS0002934317302206Alan Ahlawat SumskiNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Aria Guidelines 2020Document14 pagesAria Guidelines 2020xtine100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 11 JPS Kawasaki Disease 2014Document24 pages11 JPS Kawasaki Disease 2014Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Content ServerDocument9 pagesContent ServerRahma RafinaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Food Allergy: A Practice Parameter Update-2014Document53 pagesFood Allergy: A Practice Parameter Update-2014B Ere VelBeNo ratings yet

- 12 NICE Fever Under 5 2018Document40 pages12 NICE Fever Under 5 2018Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0091674917309193Document9 pagesPi Is 0091674917309193Annisa YutamiNo ratings yet

- 10 AAP Allergy 2019Document13 pages10 AAP Allergy 2019Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in The United StatesDocument58 pagesGuidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in The United StatesErico Marcel Cieza MoraNo ratings yet

- Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Volume 51 issue 9 2012 [doi 10.1016%2Fj.jaac.2012.07.004] Adelson, Stewart L. -- Practice Parameter on Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual Sexual.pdfDocument18 pagesJournal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Volume 51 issue 9 2012 [doi 10.1016%2Fj.jaac.2012.07.004] Adelson, Stewart L. -- Practice Parameter on Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual Sexual.pdfKharisma FatwasariNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Allergy Diagnostic TestingDocument149 pagesAllergy Diagnostic TestingIoana-NicoletaNicodimNo ratings yet

- Urticaria 2014Document8 pagesUrticaria 2014Beny RaNo ratings yet

- 8 AAP NRP - The Science Behind The Changes 2016Document37 pages8 AAP NRP - The Science Behind The Changes 2016Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- Ad Part 4Document16 pagesAd Part 4Flor OMNo ratings yet

- AAD Atopic Dermatitis - Phototherapy and Systemic Agents 2014Document42 pagesAAD Atopic Dermatitis - Phototherapy and Systemic Agents 2014Yan Zhen YuanNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- WHO Guidelines For Newborn CareDocument26 pagesWHO Guidelines For Newborn CareMamoni MaityNo ratings yet

- Management of Atopic Dermatitis - 4Document14 pagesManagement of Atopic Dermatitis - 4Christian SalimNo ratings yet

- Nilufa Shariff - Pain Dissertation PresentationDocument31 pagesNilufa Shariff - Pain Dissertation PresentationNilufar JivrajNo ratings yet

- Heavenly Spa MenuDocument2 pagesHeavenly Spa MenuDeTaaliNo ratings yet

- Catálogo de Dispositivos PQS 2014 PDFDocument318 pagesCatálogo de Dispositivos PQS 2014 PDFGestion Biomedica Prosalco IPSNo ratings yet

- Biomechanics of Edentulous StateDocument15 pagesBiomechanics of Edentulous StateNadeemNo ratings yet

- Michigan State and Local Public Health COVID-19 Standard Operating ProceduresDocument19 pagesMichigan State and Local Public Health COVID-19 Standard Operating Proceduresfebri rizaldyNo ratings yet

- UNICEF Annual Report 2019Document68 pagesUNICEF Annual Report 2019Volodymyr DOBROVOLSKYINo ratings yet

- Stree Rog 4Document11 pagesStree Rog 4Sambamurthi Punninnair NarayanNo ratings yet

- Infectious Disease Act, 2020 (1964)Document3 pagesInfectious Disease Act, 2020 (1964)Bijay ThapaNo ratings yet

- Eat Yourself Smart: Britain Faces Airlift DeadlineDocument64 pagesEat Yourself Smart: Britain Faces Airlift DeadlineNidhi BhartiNo ratings yet

- Running Head: QSEN 1Document11 pagesRunning Head: QSEN 1Mariam AbedNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- IUM-First Aid, Safety Concept (1594)Document7 pagesIUM-First Aid, Safety Concept (1594)Risad ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 Digestive SYSTEM WorksheeetDocument8 pagesPaper 2 Digestive SYSTEM WorksheeetOmar AlfrouhNo ratings yet

- Research Article Smilacina Japonica A. Gray: Antifungal Activity of Crude Extract From The Rhizome and Root ofDocument10 pagesResearch Article Smilacina Japonica A. Gray: Antifungal Activity of Crude Extract From The Rhizome and Root ofJolianna Andrea Beatrice BallezaNo ratings yet

- Hydrotherapy Principles & TechniquesDocument75 pagesHydrotherapy Principles & TechniquesSANLAPAN SAHOONo ratings yet

- T10 FinDocument12 pagesT10 FinalejandraNo ratings yet

- Week 3 (20!09!2021) Compe Law ProvisionsDocument18 pagesWeek 3 (20!09!2021) Compe Law ProvisionsNeil FrangilimanNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Form (Sample)Document1 pageVaccination Form (Sample)Godfrey Loth Sales Alcansare Jr.No ratings yet

- Clobazam As First Add On What Is The Evidence and Experience - Final Deck - 14 Feb 2023Document51 pagesClobazam As First Add On What Is The Evidence and Experience - Final Deck - 14 Feb 2023veerraju tvNo ratings yet

- Manual CCTT I y II PDFDocument77 pagesManual CCTT I y II PDFJosé LuccaNo ratings yet

- Child Health COURSE PLAN M.SC 2 YEARDocument49 pagesChild Health COURSE PLAN M.SC 2 YEARSanthosh.S.UNo ratings yet

- BAB 6. True and False StatementDocument5 pagesBAB 6. True and False StatementLentera DakwahNo ratings yet

- Khatib2017 PDFDocument14 pagesKhatib2017 PDFluxmansrikanthaNo ratings yet

- OMES-protocol OMDDocument9 pagesOMES-protocol OMDMaritzashuNo ratings yet

- Suicide Prevention and Intervention: HelplinesDocument1 pageSuicide Prevention and Intervention: Helplinesdesignbox91No ratings yet

- Exercise 3. Handling and Mass Production of Biological Control AgentsDocument5 pagesExercise 3. Handling and Mass Production of Biological Control AgentsRoxan AngonNo ratings yet

- Hsslive-Xi-Zoology-Rev-Test-4-Qn-By-Zta-Malappuram (1) - 230212 - 105754Document5 pagesHsslive-Xi-Zoology-Rev-Test-4-Qn-By-Zta-Malappuram (1) - 230212 - 105754എസ്സാർപി ഊരുചുറ്റൽ തുടരുന്നുNo ratings yet

- Baby Thesis RevisedDocument20 pagesBaby Thesis RevisedSanjoe Angelo ManaloNo ratings yet

- Vaccine Excipient & Media Summary: Excipients Included in U.S. Vaccines, by VaccineDocument4 pagesVaccine Excipient & Media Summary: Excipients Included in U.S. Vaccines, by VaccineZeljko RasoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Deep Breathing on Blood Pressure in Hypertensive PatientsDocument10 pagesEffect of Deep Breathing on Blood Pressure in Hypertensive PatientssendyNo ratings yet

- Pentasa Tablets and Sachets PIDocument14 pagesPentasa Tablets and Sachets PIGeo GeoNo ratings yet

![Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Volume 51 issue 9 2012 [doi 10.1016%2Fj.jaac.2012.07.004] Adelson, Stewart L. -- Practice Parameter on Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual Sexual.pdf](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/374100827/149x198/36f7ea4b2c/1521290598?v=1)