Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PM and Gender

Uploaded by

samsheejaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PM and Gender

Uploaded by

samsheejaCopyright:

Available Formats

PAPERS An Exploratory Study of Gender in

Project Management: Interrelationships

With Role, Location, Technology, and

Project Cost

Linda S. Henderson, School of Business and Professional Studies, University of

San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

Richard W. Stackman, School of Business and Professional Studies, University of

San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

ABSTRACT ■ INTRODUCTION ■

This study explores whether gender differences omen are taking on more roles in project management

in project managers are related to gender differ-

ences in their team members. Gender differ-

ences are explored in the context of project

managers’ and team members’ location to one

another, the project team’s use of technology,

and the cost and size of the project teams.

W (Neuhauser, 2007), yet the field is still considered to be male-

dominated (Mulenburg, 2002). The number of gender studies in

the project management literature are relatively small, a state

reflective of a historical trend in the organizational literature. As Martin (2000)

stated, “within organizational studies, research on gender has consistently

been marginalized or ignored, and most mainstream scholarship continues

Using log-linear analysis of 563 project team to be presented as if theories and data were gender-neutral” (p. 207). Over the

members’ responses, several significant find- past decade, the type and frequency of gender studies in the management

ings are reported—including the likelihood of and organizational literatures have increased (e.g., Bartol, Martin, &

same-gender project manager and team member Kromkowski, 2003; Charlesworth & Baird, 2007; Timberlake, 2005), yet a gap

dyads as well as gender differences in project still exists within the project management literature. More recent research in

contextual factors. Implications for organiza- project management has focused on gender-related issues, assumptions, and

tional and project management researchers dynamics that are endemic to the profession (e.g., Lindgren & Packendorff,

and decision makers conclude the article. 2006; Thomas & Buckle-Henning, 2007). To date, however, no studies have

been conducted that consider differences and relationships between gender

KEYWORDS: communication competency; and important contextual factors in managing contemporary projects.

project team satisfaction; project team The purpose of our study is to contribute to the literature of gender

productivity; virtuality; geographic dispersion; research in project management in order to understand better the project

technology-mediated communication context and relationships within which gender differences occur. Our goal is

especially important and timely with the rise of project management as a

critical part of our modern organizations and the economy (Lee-Kelley,

2002). Specifically, we explore whether gender differences in project man-

agers are related to gender differences in team members. We explore these

differences in the context of project managers’ and team members’ location

to one another, their use of technology, and the cost and size of their identi-

fied projects. Using log-linear analysis of 563 project team members’

responses to a survey administered through the website Chief Project Officer

(www.chiefprojectofficer.com), we report several significant findings. In par-

ticular, we report the odds ratios for female and male project managers and

team members in relationship to one another as well as in relationship to

Project Management Journal, Vol. 41, No. 5, 37–55 differences in the project contextual factors. We also report unexpected dif-

© 2010 by the Project Management Institute ferences between gender and team members’ ages and functional special-

Published online in Wiley Online Library ization in information technology. Several implications for organizational

(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/pmj.20175 and project management researchers and decision makers are discussed,

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 37

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

which encourage future changes in the human and social capital development. 26.6% female in telecommunications.2

gender imbalance of project manage- Studies of gender in project-based Gale and Cartwright (1995) isolated how

ment research and practice. work started to appear in the literature women have encountered more prob-

almost 15 years ago (e.g., Gale & lems than males gaining entry and

Cartwright, 1995). Although small in acceptance in the project environments

Literature Review number within the project management of industries that are seen as “masculine”

Gender academic literature, this emergence of in orientation. They further contend

In the past decade, a number of gender- interest in gender corresponds to the that since the culture of project-based

related review articles have been pub- high growth rate of the project manage- industries is inherently masculine in ori-

lished that focused on gender differences ment profession in the workplace. In entation, a culture change will not neces-

with respect to inequality in employ- 2009, the Project Management Institute sarily occur merely as a result of an

ment and work organizations (Mills, (PMI), the major professional associa- increase in the critical mass of women

2003; Reskin, 2000; van der Lippe & van tion in the field, reports over 500,000 entering this environment (Gale &

Dijk, 2002), human capital investment members and credential holders world- Cartwright, 1995).

and its effect on authority and power wide (Project Management Institute, While many researchers view the

relationships (Smith, 2002; Stewart & 2009). According to PMI’s 2008 complexity of gender inequality as

McDermott, 2004), and the impact of Membership Satisfaction Study, the gen- embedded within organizational cul-

stereotypes and overcoming stereo- der breakdown of membership is 70% tures, Martin (2008) maintains that

types (Rudman & Phelan, 2008). male and 30% female. In addition, in when numbers are few, women have

Although none of the articles specifical- the results of PMI’s 2008 Pulse of the predictable problems such as “height-

ly address gender and project manage- Professional Survey, 32% of Project ened visibility, performance feedback

ment, they do highlight that there is still Management Professionals (PMPs®) are skewed too positive or too negative,

much to be learned about personal and female and 68% male.1 Historically, proj- [and] slow promotions and inequitable

structural characteristics and how ect management has been a male- pay” (p. 12). To reduce these problems,

these characteristics interact in creat- dominated discipline, and the relative the number of women must increase to

ing different outcomes (e.g., future absence of gender-related studies 40% to reach a tipping point where

earnings capacity, status, and career reflects this dominance (Mulenburg, morale and performance soar (Martin,

advancement) between men and 2002); however, there is a greater num- 2008). This tipping point is supported

women. Each article overtly states, or at ber of women who are taking on roles in by Ely’s (1994) earlier research that

least implies, that gender does matter managing and participating on project showed a reduction in negative percep-

at work. teams (Neuhauser, 2007). The establish- tions of women when they occupy

Asymmetrical experiences in the ment of the Women in Project Manage- more than 15% of the organization’s

workplace—including project teams— ment Special Interest Group within the leadership roles.

for women regarding experience and Project Management Institute attests to From a cultural perspective, Buckle

knowledge gained can result in differen- this gender-role shift. and Thomas (2003) and Thomas and

tial outcomes or catch-22 situations. According to Gale and Cartwright Buckle-Henning (2007) explicated

Smith (2002) notes that differential (1995), women have been underrepre- and differentiated masculine and femi-

investments in education, work experi- sented in traditional project-based nine logic systems in an effort to better

ence, training, and hours worked industries such as construction and understand how they are embedded in

appear to enhance authority changes engineering just as they have been the project management profession

for both men and women, but men underrepresented in the general man- itself and how practicing project man-

seemingly enjoy a higher return than agement arena. The current breakdown agers view this distinction and rele-

women. And while project teams may for the top five project management vance to their work. These researchers

provide an ideal situation for women to industries is 93.5% male and 6.5% used the concepts of masculinity and

demonstrate their competence and female in construction, 71% male and femininity in reference to different ways

capabilities, Rudman and Phelan (2008) 29% female in consulting, 52.1% male of knowing and behaving, not necessar-

argue that women must disconfirm and 47.9% female in financial services, ily to differences between males and

female stereotypes in order to be con- 68.7% male and 31.3% female in infor- females. In their first study, Buckle and

sidered competent leaders even though mation technology, and 73.4% male and Thomas (2003) examined the implicit

they face negative perceptions for gender assumptions within the Project

1Data provided by Jennifer McCaffrey, Market Research

appearing too ambitious and self- Management Institute’s A Guide to the

Supervisor, PMI, August 2009.

promoting. Clearly, experience within 2Custom study for PMI by Mediamark Research and Project Management Body of Knowledge

project teams is also important to Intelligence, LLC, July 2009. (PMBOK ® Guide), which provides:

38 December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

a common language for project (Lee & Sweeney, 2001). In particular, short period” (p. 100). The researchers

managers and common standards of

female project managers appeared to surmised that the project was “regarded

project management quality, excel-

explain their reasoning and rationale both as a means, [though] unintention-

lence, and professionalism. As a

for requests more frequently than al, for reproduction of gendered organi-

documented standard of how proj-

ect managers ought to construct and male project managers. They reported zational practices and as a first step

define their success, PMBOK pro- female project managers as not threaten- towards less male-centered organiza-

vides powerful messages about legit- ing to give team members unsatisfactory tional practices [especially in the male-

imate ways of thinking and behaving performance appraisals as frequently as dominated auto industry]” (Styhe et al.,

(2008, p. 434). male project managers, and frequently 2005, p. 104).

obtaining advance support from higher In summary, the current research

Using the literary device of decon- management to back up their requests literature on gender in project manage-

struction and a qualitative text analysis (Lee & Sweeney, 2001). Research by ment has substantiated the historical

of the PMBOK ® Guide, Buckle and Richmond and Skitmore (2006) also male dominance of this professional

Thomas (2003) found “that masculine showed minor overall differences discipline and points toward a signifi-

concepts and conceptions exert a far between female and male project man- cant need for researchers to examine

more direct influence over how the con- agers in how they coped with stress. gender differences in the context of

tent of project management practices are Female project managers identified variables important to successful proj-

defined than do the feminine ones” work overload and uncertainty as ect management. According to

(Lindgren & Packendorff, 2006, p. 843). sources of stress, whereas male project Lindgren and Packendorff (2006), the

Buckle and Thomas added, “Masculine managers identified delegation and specific need is to research gender

sense making tends to value indepen- interpersonal conflict. in terms of “the individuals’ situation in

dence, self-sufficiency, separation, In contrast, Lindgren and the workplace” (p. 862). The central sit-

power deriving from hierarchical author- Packendorff (2006) conducted an uation for better understanding gender

ity, competitiveness, and analytical and in-depth narrative study of individuals differences in project management lies

impersonal problem solving” (2003, on the same project team in order to with the roles that individuals assume

p. 434). However, in a subsequent study understand how project work reflects on project teams.

of practicing project managers, Thomas ongoing patterns of femininity and

and Buckle-Henning (2007) found both masculinity in society. Their research Roles

masculine and feminine logic systems to showed how project team members’ Contemporary project management

be crucial in the thinking and behavior of acceptance of demands on cost and relies on team-based structures to

successful project managers. Buckle and time efficiency, to the exclusion of other accomplish collective work efforts.

Thomas noted, “Feminine sense making relevant work and life concerns, perpet- These structures emanate from the

involves placing primacy on one’s con- uates the masculinization of project complexity of specialized and often dis-

nection with others. Such individuals work practices. Lindgren and tributed knowledge workers who are

value sharing power and information, Packendorff noted, “It is often a mas- required to accomplish project goals

prize democratic or participative decision- culinization hidden behind seemingly across industries and global contexts.

making, and tend to create cooperative ‘feminine’ rhetoric on equality and flex- In addition, project work often exists in

work settings” (2003, p. 435). Both the ibility, rhetoric that redirects attention dynamic organizational and market-

male and female project managers inter- from collectives to individuals and pre- place environments that place a premi-

viewed in their study exhibited “sophisti- sumes real equality instead of differ- um on project teams who can adapt

cated skill in balancing masculine and ences” (2006, p. 863). Indeed, in a case quickly and creatively to the uncertainty

feminine cognitive styles and attribute study of an all-female core project and ambiguity that affect the well-

their success to ‘dancing in the white team, Styhe, Backman, and Borjesson known triple constraints of time,

spaces’ between the lines laid out by the (2005) found that these women, all resources, and outcome. The roles that

PMBOK” (p. 552). automotive engineers and designers, team members take in managing proj-

Thomas and Buckle-Henning’s initiated and accepted authority to ects are an important dimension

(2007) findings offer insight for earlier develop a concept car aimed at the for analyzing contextual factors in the

research that showed no statistical dif- needs and desires of independent, pro- management of projects and teams

ference in the use of influence strate- fessional women. Their project led to a (Crawford & Pollack, 2004). Two roles in

gies between female and male project successful presentation at a major car particular are critical in this regard: proj-

managers (Bohlen, Lee, & Sweeney, show and was seen as an extraordinary ect manager and core team member.

1998; Lee & Bohlen, 1997). Only minor event in which dominant social prac- Project managers are responsible

differences due to gender were found tices were “turned upside down for a for directing the efforts of a project team

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 39

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

to define the scope, create a plan to Project Management Institute (68% to 2007), self-disclose less, and send

accomplish the scope requirements, 32%, respectively) suggests that females shorter messages than female-only

and successfully implement the plan on may experience less participation and or mixed-gender virtual teams (Savicki

time, within budget, and at the expected greater role incongruity than males in et al., 1996). Cortesi (2001) found that

level of quality (Knutson, 2001). Project both project manager and core team males tend to talk more than females

managers also significantly influence member roles. Role incongruity for when using audio conferencing tech-

the creation of a positive, highly moti- female project managers can also repre- nologies. It also appears that virtual

vated project environment (Schmid & sent status incongruity between the team members pay less attention to the

Adams, 2008). The role of core team more influential role of project manager in-group/out-group differences evinced

member has become inculcated within (as opposed to core team member) and by gender when they work virtually as

the project management profession and their lower citizenry status compared opposed to face-to-face (Martins et al.,

used not only with primary projects, but with men (Rudman & Phelan, 2008). 2004). The complexity resulting from

also with vendors and other outside This type of incongruity can diminish dependence and dispersion has also

stakeholders (Graham, 2000). Reich the status women have earned based on played a role in several gender-neutral

(2007) found that project success relies their achievements (Berger, Webster, studies on the costs and benefits of vir-

upon the maintenance of core team Ridgeway, & Rosenholtz, 1986). The tual project teams. For example,

member composition throughout a implications of these findings have sig- researchers at Intel found that the geo-

project, which is also the key success nificance not just for roles, but also for graphic dispersion of over 1,000 project

factor in ongoing alliances between two other project contextual factors: team members did not appear to sig-

operating and engineering companies location and technology. nificantly detract from overall team

(Zhang & Flynn, 2003). According to performance (Lu, Watson-Manheim,

McDonough and Spital (2003), core Location and Technology Chudoba, & Wynn, 2006). However,

teams are important in effectively man- The rapid growth of project management these researchers did find that overuse

aging project portfolios having high over the past two decades has paralleled of different communication technolo-

uncertainty. Equally important are core the information technology explosion gies across different team environments

team members’ judgments in accom- and, in particular, the legitimization of did reduce performance. Lee-Kelley

plishing a successful project risk analy- virtual work in which project team mem- (2006) found that project team mem-

sis (Chapman, 1998), managing knowl- bers are commonly located at a geo- bers who work virtually experience a

edge (Eppler & Sukowski, 2000), and graphical distance from one another. “distinct feeling of discomfort and

facilitating networks (Hutt, Stafford, Working virtually requires reliance upon unease” (p. 240), especially when other

Walker, & Reingen, 2000). technology-mediated communication to team members are part of different

Grabher (2004) described core accomplish project planning and imple- organizations.

teams as an essential element of project mentation. Gibson and Cohen (2003) use From the perspective of different

ecologies. In this sense, their function the term virtuality to describe the con- functional workgroups, Van den Bulte

and impact are not only relevant to the tinuum upon which teams may exist in and Moenaert (1998) found that team

practice of project management, but terms of their dependence on technolo- communication is enhanced in some

also may reflect cultural norms of their gy-mediated communication and degree functional groups when they are

larger organizational environments. of dispersion. colocated (e.g., R&D), yet negligibly

Core team membership is not necessar- A dearth of research exists that exam- altered for others when working virtually

ily part of defined hierarchical positions ines gender in virtual team environ- (e.g., marketing). Along the same lines,

and structures since their composition ments. However, the existing research research by Patti, Gilbert, and Hartman

usually occurs within matrix or flat does suggest that virtuality may obviate (1997) of product development projects

organizational structures (Lindgren & particular gender dynamics found in in 82 firms showed that the schedule per-

Packendorff, 2006). Yet their composi- larger organizational settings. For formance and product quality signifi-

tion may represent role incongruity in example, females report higher trust cantly benefited when team members

regard to gender. For example, Rudman than males (Furumo & Pearson, 2007) were colocated. Sharifi and Pawar

and Phelan (2008) identify research that and greater satisfaction in general (2002) found that project team members

shows general work roles as more segre- (Martins, Gilson, & Maynard, 2004), perceived co-location to be a better con-

gated and gender-stereotyped for even on female-only virtual teams text for team development, yet viewed

women when men are disproportion- (Savicki, Kelley, & Lingenfelter, 1996). In their virtual performance as influenced

ately represented in positions of author- terms of communication on virtual more by effective team management.

ity. The larger number of male versus teams, males are less able to dominate As previously suggested, the degree

female PMP® credential holders in the team interaction (Furumo & Pearson, of virtuality no doubt influences the

40 December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

nature and quality of communication Project Cost tant subprocess connected to project

among project team members. Historically, project cost constitutes costing: levels of technology usage. In

DeSanctis and Monge (1998), in their one of the triple constraints—schedule, their study of 209 capital facility proj-

review of research on technology- cost, quality—in project management ects, they found significant relation-

mediated communication, found that and is often the most critical in terms of ships between the cost of medium and

message bias can decrease, but under- measuring project success. Managing small projects, the technology used on

standing and comprehension can project cost is a fundamental responsi- these projects and project success. The

increase. In addition, an individual’s bility of project managers, and it is one cost of small-sized projects was $5 mil-

ability to form interpersonal impres- aspect to which project managers are lion or less; medium-sized projects

sions and build relationships takes held accountable. According to Smith cost between $5 million and $50 mil-

longer because these communication (2002), control over monetary resources lion. Their research supports a strong

attributes generally require interac- such as project cost has different gen- relationship between project cost,

tions over time to make sense of social der implications for women and men in technology usage, and ultimate project

cues (Walther, 1993). the workplace. Smith writes, “Men success.

More recently, Henderson (2008) receive twice the economic payoff that Kuehn (2006) also encapsulates the

found a positive relationship between women receive for possessing authority area of risk within project cost estimat-

geographic dispersion of the project that allows them to control monetary ing and comprehensive mitigation

team and the team members’ percep- resources even when gender differ- strategies—a conceptual and practical

tions of their respective project man- ences in education and experience are framework advocated by many theo-

agers’ ability to decode communication. considered” (2002, p. 534). Men draw rists and practitioners in the field.

In addition, there was a positive associ- this economic payoff primarily from Buckle and Thomas (2003) have shown

ation between geographic dispersion having greater numbers in positions of that the project management profes-

and team member satisfaction when authority where controls over monetary sion as demonstrated in the PMBOK

project team members colocate with resources generate larger income than “reveals a strongly masculine orienta-

their project manager. Geographic dis- for women. tion to issues of risk . . . describing how

persion also operated as a double- Notwithstanding the overall state of uncertainties (i.e., risks) ought to be

edged sword in that it was negatively gender inequity in managing monetary identified, structured, and controlled

related to team members’ perceptions resources, project cost can entail sever- through various tactics or methodolo-

of their team’s productivity even when al subprocesses that have implications gies, budgets, and reporting” (p. 438).

team members who were colocated for their inherent masculine orienta- Though Buckle and Thomas (2003) do

with their project managers perceived tion (Buckle & Thomas, 2003). Subpro- not dispute the obvious responsibility

them (project managers) to be compe- cesses can entail estimating, budgeting, that project managers have to mini-

tent communicators. In other words, the accounting, monitoring and tracking, mize project cost through risk manage-

co-location of respondents with their controlling variances, taking corrective ment practice, they do call into question

respective project managers may pro- actions, and generating overall perfor- what is lost with an overreliance on

duce sufficient interactions for team mance metrics of earned value and/or masculine logic systems in risk man-

members to feel satisfied with their return on investment (Dinsmore & agement and project cost control. Such

work on the project, but not necessarily Cabanis-Brewin, 2006). In addition, practice may “prevent new information

clear and/or confident about the pro- some or all of these subprocesses from influencing project processes or

ductivity of their geographically dis- require coordination in their use desired outcomes [and] creativity from

persed team (Henderson, 2008). according to the particular phase of a entering the project life cycle” (p. 439).

Given the paucity of research con- project—from initiation to planning This prevention in turn can exacerbate

cerning gender in virtual project teams through implementation and finally risk and cost problems since the major

and the importance of this contextual closeout. According to Kuehn (2006), in sources of risk in “complex projects

structure in project management, the her recent book on integrated cost and come from changes that are externally

present study seeks to shed light on schedule control, the various sub- imposed and difficult, sometimes

gender differences between project processes of project costing and coordi- impossible, to predict in advance”

managers and core team members who nation need to allow for flexibility to (Remington & Pollack, 2007, p. 69).

are colocated or dispersed. In addition, scale costs to match changing condi- The catch-22 for many project

the present study explores these differ- tions (for example, customer or spon- managers regarding project cost lies in

ences when project teams are dispersed sor scope changes, unavailability of key the distinction between their responsi-

and reliant on technology-mediated resources, etc.). Yang, O’Connor, and bility and accountability for managing

communication. Wang (2006) researched another impor- these costs, often without the formal

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 41

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

organizational authority to determine adding more people to a late project Methodology

or allocate them. According to Cohen only makes it later. Perhaps this To explore gender differences and their

and Bradford (2005), influence requires explains why Ali, Anbarri, and Money interrelationships with project contex-

a number of cognitive, behavioral, and (2008) recently found that the size of a tual factors, we analyzed particular

interpersonal approaches, ones that project team has no relationship with items and scales from questionnaire

project managers need in varying its use of project management software data of project team members in a larg-

degrees to determine and manage proj- ideally intended to better manage the er, ongoing study of project communi-

ect costs. These approaches include project. cation and network relationships. The

assuming that all stakeholders are Conversely, if team size increases questionnaire was made available to

potential allies as opposed to competi- with people who have the right expertise participants through an Internet survey

tors, clarifying goals and priorities, to fit immediate demands, there may be company. We composed a letter that

diagnosing the world of the other per- no negative impact on a project sched- introduced the general parameters of

son (e.g., functional managers, cus- ule. In a study of field data from 200 soft- our study and requested the readers’

tomers, sponsor, stakeholders, vendors, ware development projects across 10 participation through a URL link pro-

etc.), dealing with relationships, and industries, Pendharkar and Rodger vided in the letter. A second company,

influencing through give and take. In (2007) found that increases in team size which owned the subscriber list to the

other words, managing project cost do not increase the software develop- original U.S.-based website Chief

does not solely rely on financial and ment effort and even decrease this effort Project Officer (now Projects at Work),

budgetary knowledge and control, but when particular coding languages are then e-mailed our letter to 4,998

depends as well on a project manager’s used. However, increases in team size subscriber e-mail addresses on three

influence skills. Most often, project can increase effort with the use of partic- separate occasions over a 14-week time

managers are not heads of divisions/ ular tools and lower-quality data. period. At the time of data collection,

departments, nor members of senior Like much of the gender-neutral Chief Project Officer was a website

management teams, yet are responsi- research previously discussed under offering professional development for

ble for delivering the project outcomes “Location and Technology,” there is lit- project professionals in a variety of

(products or services) within financial tle known about how gender differences roles, with a special emphasis on strate-

constraints typically imposed on between project managers and team gies for senior management project

them by senior management (Sahdev, members relate to this all-important decision makers. A total of 657 sub-

Vinnicombe, & Tyson, 1999). As Thomas contextual factor of team size. There scribers from North America completed

and Buckle-Henning (2007) found, proj- may indeed be significant interactions the questionnaire during that time peri-

ect managers need a balance of mascu- between gender and team size that, od, resulting in 5633 useable responses.

line and feminine logic systems and heretofore, have not only been over- Ninety-three responses were excluded

sense making to discern and influence looked in the literature, but also may from the total because the respondents

issues of risk and cost-effectiveness. shed new light on the role gender plays identified themselves as the actual proj-

in the influence of team size. ect managers under question.

Team Size The questionnaire instructions stat-

A corollary to project cost in determin- Research Questions ed: “This survey asks for your judge-

ing the size of a project is the size of the Based on the previous literature review, ments of a particular project manager

project team. Team size is a common we explore the following research ques- and team with whom you have recently

constraint encountered by project tions in the remainder of this article. worked. Please take a few minutes to

managers. In her study of project lead- • What are the relationships among the think of this project manager, the nature

ers in 17 clinical research organiza- project contextual factors of roles, of the project, and the members of the

tions, Lee-Kelley (2002) found that location, technology, cost, and size? project team. Then respond to the state-

“team size can exert significant influ- • Do gender differences exist between ments and questions in the following

ences on the project leader’s perception project team members and these con- sections.” Periodic reminders to main-

of control, which in turn is likely to textual factors? tain this perspective were embedded in

affect his/her view of the apparent diffi- • Do gender differences exist between the questionnaire. An example reminder

culty of certain project objectives” project managers and these contextu- was to “keep thinking of the same proj-

(p. 475). Borrowing from Brooks (1978) al factors? ect manager and project team.”

and his well-known The Mythical Man- • What are the differences and interre-

3While there were 563 usable responses, only 561 ques-

Month, communication overhead can lationships among project team

tionnaires reported the gender of the project manager.

increase exponentially as team size members and project managers with The two missing data points did not affect the log-linear

increases, which leads to the reality that respect to project contextual factors? analysis.

42 December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

The questionnaire items (see discrepant from those observed” power in no way affected our ability to

Appendix A) used in this study included (Bakeman & Robinson, 1994, p. 50). uncover and report—in meaningful

demographic and contextual questions The interpretation of log-linear ways—the significant results outlined

of the respondents and their target proj- analysis results is based on two chi- and then discussed in the remainder of

ect managers and project teams. Closed- square goodness-of-fit tests in which a this article.

ended items included: nonsignificant result is interpreted as

• Gender of respondent and target proj- the model perfectly fitting the data Results

ect manager (Field, 2005; Rojewski & Bakeman, Frequency counts for each variable are

• Age of respondent and target project 1997). The first goodness-of-fit test provided in Table 1. Most noteworthy,

manager addresses whether the proposed model 30% of our subjects, all from North

• Location: Did/does this project man- is a good fit for the data. If the result is America, are female (n ⫽ 168) and 70%

ager work at the same location as you not significant, one proceeds to the sec- are male (n ⫽ 393). These percentages

work/ed? ond goodness-of-fit test, which helps are identical to the gender breakdowns

• Dispersion: Keep thinking of the same isolate the model variables (including from the PMI 2008 Membership

project manager and project team. To potential higher-level associations Satisfaction Study, and nearly identical

what degree were/are the members of between variables) that can be removed to the results from PMI’s 2008 Pulse of

this project team geographically dis- without significantly affecting the pre- the Professional Survey (see the

persed? dictive power of the model (Field, “Literature Review” section). However,

• Technology usage: To what degree did 2005). Again, a nonsignificant result is recent results of the gender breakdown

this project team rely on technology- interpreted as the model that best fits in PMI’s North American membership,4

mediated communications rather the data, and because of the hierarchi- which constitutes the same geographic

than face-to-face interaction to cal nature of log-linear analysis, one region as our sample, show that 58.1%

accomplish tasks? (Note: technology- focuses only on the remaining highest- are male and 41.9% are female—a

mediated communications include level interaction(s) for interpretation breakdown representative of the 40%

telephone, faxes, teleconferences, and model building purposes. females necessary for the critical mass

e-mail, videoconferences, collabora- Critical to conducting log-linear and change advanced by Martin (2008).

tive design tools, and knowledge analysis is the creation of cross tabs for Our sample differs by 11.9% more for

management systems.) each model in order to assess whether both males and females, thus reflecting

• Cost of identified project no more than 20% of the expected cell the overall PMI membership more

• Size of project team counts have less than five observations closely than its North American contin-

(six distinct sets of cross tabs are provid- gent.

Open-ended, write-in questions ed in Appendix B; Field, 2005). If this Based on our research questions,

included: assumption cannot be met, there are four specific combinations of variables

• What was your role on this project two potential remedies—outside of col- and their respective models were tested

team (i.e., core team, extended team, lecting more data—available to using log-linear analysis. These combi-

stakeholder, client/customer, con- researchers (Field, 2005). One is to accept nations include: contextual (project-

tractor, other)? the loss of power. The other is to com- related) variables (Table 2), project

• What is your functional area of work bine categories within variables to team members with contextual vari-

(e.g., engineering, marketing, infor- increase frequency counts. We chose ables (Table 3), project managers with

mation technology, etc.)? to combine categories for six of the 11 contextual variables (Table 4), and proj-

variables (see Appendix A). We wanted ect team members and project man-

Analysis to prevent a loss of power when testing agers with contextual variables (Table 5).

We applied log-linear analysis to study more complex models—that is, models For all four combinations of variables

the gender composition of project with three or more categorical variables. and their respective models, the initial

teams across contextual (project team) When there are significant higher- chi-square goodness-of-fit tests were

variables. Used in model building and level associations, the results from log- nonsignificant.

testing, log-linear analysis allows for the linear analysis can be “elegantly” Specific to the contextual (project-

study of possible associations between reported in terms of odds ratios (Field, related variables; see Table 2), signifi-

two or more categorical variables and 2005, p. 717). Odds ratios are easiest to cant higher-order associations included

their observed frequencies (Rojewski & understand when variable categories team dispersion and team tech usage

Bakeman, 1997) toward the identifica- can be combined into 2 ⫻ 2 contin-

tion of the “simplest model that still gency tables (Field, 2005). Ultimately, 4Custom study for PMI by Mediamark Research and

generates expected frequencies not too our decision to guard against a loss of Intelligence, LLC, July 2009.

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 43

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

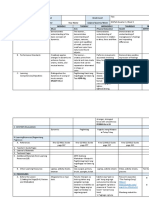

Variable Variable Descriptors Count included a three-way effect for project

team member gender and location and

Project Manager Gender (1) Female 168

PMGen (2) Male 393 project manager gender

(2(26) ⫽ 162.8, p ⬍ 0.001) and a signif-

Project Manager Age (1) 40 and over 368 icant association between project man-

PMAge (2) 39 and under 195 ager gender and project team member

Team Member Gender (1) Female 177 function (p ⬍ 0.05). The significant

TMGen (2) Male 386 association between project team gen-

der and role (p ⬍ 0.05) is noteworthy

Team Member Age (1) 40 and over 395

TMAge (2) 39 and under 168 because it was not significant in the

model results for project team mem-

Team Member Role (1) Core team 211 bers only (see Table 3).

Role (2) Noncore team 352 Finally, Tables 2 through 5 identify

Team Member Function (1) IT 212 significant association results reported

Funct (2) Non-IT 351 earlier. The consistency with which pre-

viously identified association results

Team Member Location (1) Same location 421

Loc (2) Different 142 remain significant in subsequent mod-

els provides additional validation for

Team Dispersion (1) Extremely and majority dispersed 143 our decisions to combine categories

Disp (over 75%) within six of the 11 variables to guard

(2) Some dispersed (50%) 110 against any loss of statistical power but

(3) Slightly dispersed (25%) 177

still be able to report significant find-

(4) Not dispersed (colocated) 133

ings in this exploratory study.

Team Tech Usage (1) Extremely or mostly reliant on 274

Tech technology-mediated communication Discussion

(2) Half of the time reliant on 154 The results of our analyses provide sev-

technology-mediated communication eral significant findings that expand

(3) Slight or no reliance on 135

our knowledge of gender differences in

technology-mediated communication

project management and their interre-

Project Team Size (1) 9 or less 204 lationships with project contextual fac-

Size (2) 10 to 24 214 tors. In this section, we first discuss our

(3) 25 or more 144 findings of the contextual project-

Project Cost (1) $1 million or less 304 related variables. We then consider the

Cost (2) Over $1 million 259 project team members (our question-

naire respondents) with the contextual

Table 1: Variables and variable descriptors.

variables followed by project managers

(identified by their respective team

(p ⬍ 0.001), project team size and proj- and p ⬍ 0.01, respectively). With respect members) and the contextual vari-

ect cost (p ⬍ 0.001), project team size to project managers (see Table 4), proj- ables. Next we look at the interactions

and team dispersion (p ⬍ 0.001), and ect manager gender and age were sig- of project team members and project

project cost and team dispersion nificantly associated with project cost managers with the contextual vari-

(p ⬍ 0.01). Interpretations of all signifi- (p ⬍ 0.01). ables. We conclude the article with lim-

cant higher-order associations are The significant four-way effect itations and suggestions for future

addressed in the “Discussion” section (2(1) ⫽ 5.183, p ⬍ 0.05) for the model research.

and in Table 6. that included project team member With respect to the project contex-

Significant higher-order associa- and project manager gender and age is tual factors (Table 2), we found a strong

tions for project team members (see of most interest (see Table 5), and relationship between project team size

Table 3) included the project team highlights the significant associations and project cost. The odds ratio (Table 6)

member function and location (p ⬍ between project team member and shows that project teams with nine or

0.01), the project team member age project manager gender, and project fewer members are almost six times

and role on the project (p ⬍ 0.05), and team member and project manager more likely to work on projects costing

the project team member gender and age. Additional model results for project $1 million or less than larger project

age in relation to project cost (p ⬍ 0.05 team members and project managers teams. Smaller project teams have

44 December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

Significant Model Chi-Square

Models Goodness-of-Fit:

[Variables] Significant Associations (Sig.) Likelihood Ratio (Sig.)

[Disp][Tech] Two-way effects, x2(6) ⫽ 139.6, p ⬍ 0.001 0.000 (n.s.)

[Size][Cost] Two-way effects, x2(2) ⫽ 140.1, p ⬍ 0.001 0.000 (n.s.)

[Size][Cost][Tech] Two-way effects, x2(12) ⫽ 149.99, p ⬍ 0.001 9.861 (0.453)

[Size][Cost] (0.000)

[Size][Cost][Disp] Two-way effects, x2(17) ⫽ 180.5, p ⬍ 0.001 8.053 (0.529)

[Size][Cost] (0.000)

[Size][Disp] (0.001)

[Size][Disp][Tech] Two-way effects, x2(28) ⫽ 193.8, p ⬍ 0.001 21.881 (0.147)

[Size][Disp] (0.000)

[Disp][Tech] (0.000)

[Cost][Disp][Tech] Two-way effects, x2(17) ⫽ 156.2, p ⬍ 0.001 4.830 (0.776)

[Cost][Disp] (0.006)

[Disp][Tech] (0.000)

Table 2: Model results: Contextual (project-related) variables.

lower project costs—a finding that sup- The odds are even higher (Table 6) that The degree of dispersion also figures

ports either of these contextual factors project teams with higher dispersion significantly in its relation to team size.

as indicators of the overall size of a among members are more likely to use Smaller project teams tend to be co-

project (Ankrah, Proverbs, & Debrah, technology-mediated communication, located, more reliant on face-to-face

2009; Lee-Kelley, 2002; Neuhauser, which reflects Gibson and Cohen’s communication, and cost $1 million or

2007; Pendharkar & Rodger, 2007). (2003) framework for virtual teams. less. As previous research by DeSanctis

Significant Model Chi-Square

Models Goodness-of-Fit:

[Variables] Significant Associations (Sig.) Likelihood Ratio (Sig.)

[Role][Funct][Loc] Main effects, x2(7) ⫽ 215.2, p ⬍ 0.001 1.373 (0.721)

[Funct][Loc] (0.006)

[TMGen][TMAge] Main effects, x2(31) ⫽ 502.8, p ⬍ 0.001 4.813 (0.903)

[Role][Funct][Loc]

[TMAge][Role] (0.020)

[Funct][Loc] (0.006)a

[TMGen][TMAge] Two-way effects, x2(18) ⫽ 165.3, p ⬍ 0.001 12.763 (0.545)

[Size][Cost]

[TMGen][Cost] (0.012)

[TMAge][Cost] (0.009)

[Size][Cost] (0.000)a

[TMGen][TMAge] Two-way effects, x2(40) ⫽ 161.8, p ⬍ 0.001 52.033 (0.251)

[Disp][Tech]

[Disp][Tech] (0.000)a

aSignificant associations reported previously.

Table 3: Model results: Project team members with contextual variables.

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 45

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

Significant Model Chi-Square

Models Goodness-of-Fit:

[Variables] Significant Associations (Sig.) Likelihood Ratio (Sig.)

[PMGen][PMAge] Two-way effects, x2(18) ⫽ 174.6, p ⬍ 0.001 8.399 (0.868)

[Size][Cost]

[PMGen][Cost] (0.001)

[PMAge][Cost] (0.001)

[Size][Cost] (0.000)a

[PMGen][PMAge] Two-way effects, x2(40) ⫽ 173.2, p ⬍ 0.001 33.452 (0.494)

[Disp][Tech]

[Disp][Tech] (0.000)a

aSignificant associations reported previously.

Table 4: Model results: Project managers with contextual variables.

Significant Model Chi-Square

Models Goodness-of-Fit:

[Variables] Significant Associations (Sig.) Likelihood Ratio (Sig.)

[TMGen][TMAge] Four-way effects, x2(1) ⫽ 5.183, p ⬍ 0.05 0.000 (n.s.)

[PMGen][PMAge]

[TMGen][PMGen] Three-way effects, x2(26) ⫽ 162.8, p ⬍ 0.001 5.183 (0.879)

[Role][Funct][Loc]

[TMGen][PMGen][Loc] (0.001)

[TMGen][PMGen] (0.000)a

[TMGen][Role] (0.040)

[PMGen][Funct] (.019)

[Funct][Loc] (0.005)a

[TMAge][PMAge] Two-way effects, x2(26) ⫽ 75.355, p ⬍ 0.001 2.981 (0.982)

[Role][Funct][Loc]

[TMAge][Role] (0.008)a

[TMAge][PMAge] (0.000)a

[Funct][Loc] (0.007)a

[TMGen][PMGen] Two-way effects, x2(40) ⫽ 292.8, p ⬍ 0.001 31.762 (0.529)

[Disp][Tech]

[TMGen][PMGen] (0.000)a

[Disp][Tech] (0.000)a

[TMAge][PMAge] Two-way effects, x2(40) ⫽ 209.8, p ⬍ 0.001 28.405 (0.695)

[Disp][Tech]

[TMAge][PMAge] (0.000)a

[Disp][Tech] (0.000)a

[TMGen][PMGen] Two-way effects, x2(18) ⫽ 288.1, p ⬍ 0.001 16.691 (0.273)

[Size][Cost]

[PMGen][TMGen] (0.000)a

[PMGen][Cost] (0.019)a

[Size][Cost] (0.000)a

[TMAge][PMAge] Two-way effects, x2(18) ⫽ 211.6, p ⬍ 0.001 13.274 (0.505)

[Size][Cost] [TMAge][PMAge] (0.000)a

[PMAge][Cost] (0.002)a

[Size][Cost] (0.000)a

a Significant associations reported previously.

Table 5: Model results: Project team members and project managers with contextual variables.

46 December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

Association Odds Ratio Interpretations

[Disp][Tech] Projects that are mostly to extremely dispersed are 4.6 times more likely to be mostly to extremely reliant on

technology-mediated communication.

[Size][Cost] Projects that have nine or fewer team members are 5.9 times more likely to cost $1 million or less.

[Size][Disp] Projects that have nine or fewer team members are 2.3 times less likely to be mostly to extremely dispersed.

[Cost][Disp] Projects that cost $1 million or less are 1.8 times less likely to be mostly to extremely dispersed.

[Funct][Loc] Core project teams members are 1.14 times more likely to be located at the same location as the project manager.

[TMGen][Cost] Female project team members are 1.5 times more likely to be on projects that cost $1 million or less.

[TMGen][Loc] Female project team members are 1.1 times less likely to be at the same location as the project manager.

[TMGen][Role] Female project team members are 1.4 times more likely to be a core team member than are male project team

members.

[TMAge][Role] Project team members 40 years old and older are 1.5 times less likely to be a project team core member than

are project team members 39 years old and younger.

[TMAge][Cost] Project team members 40 years old and older are 1.7 times less likely to be on projects costing $1 million or

less than are project team members 39 years old and younger.

[PMGen][Cost] Female project managers are 1.9 times more likely to be assigned to projects costing $1 million or less than

are male project managers.

[PMGen][Loc] Female project managers are 1.3 times less likely to be at the same location as project team members.

[PMGen][Funct] Female project managers are 1.4 times more likely to work with IT-functional project team members than are

male project managers.

[PMAge][Cost] Project managers 40 years old and older are 2.1 times less likely to be assigned to projects costing $1 million

or less than project managers 39 years old and younger.

[TMGen][PMGen] Female project team members are 9.0 times more likely to be assigned to female project managers than are

male project team members.

[TMAge][PMAge] Project team members who are 40 years old and older are 3.4 times more likely to be assigned to project man-

agers 40 years old and older than are project team members 39 years old and younger.

Table 6: Significant associations’ odds ratio interpretations.

and Monge (1998), Wallace (2004), and same location as their respective proj- Female project team members are

Walther (1993) showed, the combina- ect managers than team members who almost twice as likely to be on projects

tion of less dispersion and lower tech- have different functional responsibili- costing $1 million or less (Table 6). This

nology usage, which account for the ties. This finding is similar in type to finding suggests that female team

majority of cases in our study, can previous research that found particular members may not be associated with

facilitate interpersonal impressions functions such as R&D and product the masculinization of project costs

among team members and aid in rela- development better suited to co-location identified by Buckle and Thomas (2003)

tionship building more speedily than (Patti et al., 1997; Van den Bulte & and thus experience less opportunity to

its opposite. Moenaert, 1998). It may well be that work on larger, more complex projects

The next log-linear analysis of proj- project team members with informa- that cost more. The previous finding

ect team members with the project tion technology expertise paradoxically that projects costing less have smaller

contextual variables (Table 3) produced require more face-to-face contact with project teams supports this implica-

several significant and noteworthy rela- their project managers than we would tion. We also found that female team

tionships. First, project team members expect by virtue of the essential role members are less likely to work at the

whose function is information technol- information technology plays in dis- same location as their respective proj-

ogy (IT) are more likely to work at the persed environments. ect managers and are more likely to

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 47

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

assume the role of core team member project managers and core team mem- projects, leaving them more marginal-

than their male counterparts. bers—to use project assignments to ized both geographically and culturally

According to Grabher (2004), the core build their careers. The role of project from power-gaining experiences in

team, when viewed as one of several manager could be a path to power. comparison to their male counterparts.

“organizational layers that are tem- Kanter (1977) wrote of “homosocial “Homosocial reproduction” (Kanter,

porarily tied together for the comple- reproduction,” which is the reproduc- 1977) appears to have transferred into

tion of a specific project” (p. 1507), tion of social characteristics of organi- the project management discipline,

represents the “elementary learning zational power structures over succes- along with the prevalent bias toward

arena of projects” (p. 1492). Female sive generations of work. If men are masculine logic systems and sense

team members may be perceived as more likely to manage projects that making (Buckle & Thomas, 2003). This

fitting best within this conceptualiza- are larger in scale (e.g., number of team “homosocial reproduction,” as repre-

tion of a core team in male-dominated members and cost of project) and thus sented in relational and organizational

project-based industries where they likely to be more visible, then they may demography, mediates a variety of

have been historically underrepre- be more likely to sustain their positions individual-level and organizational-

sented (Gale & Cartwright, 1995). in the organizational power structure. level outcomes at work (Tsui & Gutek,

Lastly, we found team members 40 Finally, project managers 40 years of 1999; Tsui & O’Reilly, 1989). Thus, the

years of age or older to be 1.5 times age or older are two times less likely to historical “glass ceiling” for women or

less likely to be on core teams than be assigned to projects costing $1 mil- “glass escalator” for men (Rudman &

members 39 years of age and under. lion or less than project managers 39 Phelan, 2008) found in general man-

From the perspective of project ecolo- years of age and younger. This finding is agement exists within contemporary

gies (Grabher, 2004), the firm(s), or consistent with that of project team project management as well.

company(s), within which a project members. It also lends credence to both The final two results from Table 5

operates as well as the larger commu- Grabher’s (2004) notion of project show that female project managers

nity of clients, suppliers, and corporate ecologies and the implication of are more likely to work with project

or organizational groups, all comprise Hodgson’s (2002) research that the role team members with an IT function than

the arena in which noncore team of the project manager is a path to are male project managers. Since team

members operate in extended rela- power in which a project manager’s members with an IT functional respon-

tionships with core team members. experience, expertise, and authority sibility are more likely to be colocated

It is probable that these extended (older and male) leads to roles on larg- with their project manager, it appears

team members, as opposed to core team er, more costly projects. that this relationship is more stable

members, are older in age given the Table 5 shows the final set of results when both team members and project

requirements for their experience, from the log-linear analysis of project managers are male. Lastly, project team

expertise, knowledge, and capabilities. team members and project managers members who are 40 years of age and

As shown in Table 4, both the gen- with the contextual variables. The most older are 3.4 times more likely to work

der and age of project managers signif- striking results concern gender. Female on teams with project managers in the

icantly interact with project cost. project team members are nine times same age group than are team members

Female project managers are almost more likely to work with female project 39 years of age and younger. As previ-

twice as likely to work on projects cost- managers than are male project team ously discussed, team members of this

ing $1 million or less than are male members. Female project managers are 40+ age group are less likely to be on a

project managers (Table 6). This finding also more likely to be dispersed from core team and, along with project man-

is consistent with the result for female team members (Table 6). These find- agers, less likely to be on projects cost-

project team members. In effect, both ings are especially critical given the pre- ing $1 million or less. Returning to

female project managers and team vious findings that female project man- Grabher’s (2004) project ecologies, these

members are significantly more likely agers and team members are more like- results collectively indicate a relation-

to work on lower-cost, smaller projects ly to work on smaller, less costly proj- ship between age and the experience

than their male counterparts. Hodgson ects. In addition, female team members and expertise found more frequently in

(2002) argues that project assignments are more likely to be dispersed from extended team members as opposed to

allow individuals to demonstrate abili- their project managers and to work on core team members.

ties, strengths, and professionalism, core teams. Taken together, these

which addresses both the responsibili- results indicate that both female project Limitations and Future Research

ty/accountability demands ascribed to managers and team members may be Our exploratory research design allows

the project manager as well as the locked in a vicious cycle of project us to report on the relationships among

opportunities for individuals—both assignments on lower-cost, smaller project contextual variables and the

48 December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

gender of project team members and region (77.4% male and 22.6% female).5 Conclusion

their respective project managers. We This area of research has direct implica- The results of our exploratory study

relied on self-report data for our results tions for cross-cultural influences on confirm the importance of gender in

and, as with other research utilizing this gender inequities within global project project management and its interrela-

methodology, care should be taken in management teams (Mills, 2003). tionships with role, location, technolo-

generalizing the results to the project We also recommend that future gy, and cost. The major contribution is

management discipline. As one way to researchers look at gender across differ- the gender makeup of project teams

obviate this concern, we asked respon- ent industries—in particular, construc- and the segregation of women on

dents to indicate whether or not the tion, consulting, financial services, smaller, less costly, more dispersed core

project they referenced in answering information technology, and telecom- project teams that rely on technology-

our survey questions was completed or munications. This recommendation mediated communication more than

ongoing. Over 70% of respondents ref- especially applies to those organiza- those of men. The limited participation

erenced current, ongoing projects. Our tions that rely upon structures in which afforded to women in these types of

use of a common method of data col- project management organizations projects calls into question their ability

lection may have limited our ability to (PMOs) and project portfolio manage- to move forward and develop human

uncover other significant results. This ment groups play a key role in the man- and social capital in contemporary

qualification may apply to the design of agement of organizations (McDonough & project environments.

the questionnaire response sets and Spital, 2003). Timberlake (2005) argues that, in

our decisions to collapse some of the Future research is also needed general, women continue to lag behind

response sets. These limitations regarding project managers’ ability to men in career advancement and in lev-

notwithstanding, our results can be select project team members (in partic- els of compensation and achieved sta-

fairly generalized due to our sample’s ular, core team members), which would tus. This is due, in part, to women’s

validation of gender breakdown by the raise the potential for additional gender inability to access social capital,

various PMI research studies discussed differences, relationships, and dynam- defined as the collective value of all

earlier. In addition, the overall results of ics. This type of focus could lead to social networks and the trust, reciproc-

our study provide a significant and future research on “success measures” ity, information, and cooperation with-

compelling view of the role that gender specific to projects—that is, timeliness in an organization (Prusak & Cohen,

in particular plays within the relation- of completion, cost overruns, and cus- 2001). Participation on project teams,

ships of project team members, their tomer satisfaction with respect to the especially as a project manager or core

project managers, and key contextual quality of ultimate project outcomes. team member, provides an excellent

factors of the project management Including these “success measures” is forum for an individual to develop

environment. important for gender comparisons social capital that spans functional and

As to future research, the results of especially with regard to how women hierarchical levels in the organization.

our study point toward the need for project managers and team members Social capital is a source of knowledge,

continued efforts to uncover and are successful regardless of the cost of resources, and networks that is essen-

understand the dynamics of gender their projects. Understanding success tial for career development and matu-

within project management. For exam- would require future research that ration (Timberlake, 2005). Timberlake

ple, any study linking gender and proj- examines the actual performance of (2005) adds that, while women may

ect teams has the potential to inform us project managers and how their behav- enter into an organization with similar

as to how personal and structural char- iors affect their teams’ performance levels of human capital as men, their

acteristics in the workplace affect men (Turner & Muller, 2005). Lastly we rec- subsequent success is not determined

and women. Besides replicating our ommend that future research consider by human capital alone. Her argument,

study with additional samples, we rec- family-related factors of both female as we interpret it, clearly illustrates the

ommend that future research also and male project managers and team importance of participation in informal

include an examination of gender members in order to understand how organizational networks.

across different geographic regions. family responsibilities may explain gen- Given the increasing importance of

The current gender breakdown of PMI der differences with respect to team projects within organizations over the

membership in North America is quite size, project cost, and dispersed versus past decade, participation in key posi-

different from that found in the Asia colocated project teams (van der Lippe & tions on projects may portend increased

Pacific region (82.4% male and 17.6% van Dijk, 2002). human and social capital along with vis-

female), Europe/Middle East/Africa ibility and thus career advancement

region (86.1% male and 13.9% female), 5Custom study for PMI by Mediamark Research and opportunities for women that could fur-

and the Latin America/Caribbean Intelligence, LLC, July 2009. ther erode the glass ceiling/sticky floor

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 49

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

barriers. However, our results highlight Brooks, F. P. (1978). The mythical man- European Management Journal, 18,

the opposite. Segregation on projects month: Essays on software engineering. 334–342.

may actually hinder a woman’s ability to Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Field, A. (2005). Discovering statistics

break through the glass ceiling or break Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of using SPSS (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks,

from the sticky floor in the project man- Computer Science. CA: Sage.

agement discipline. Reskin (2000, p. 707) Buckle, P., & Thomas, J. (2003). Furumo, K., & Pearson, J. M. (2007).

says it best: “Inequality at work does not Deconstructing project management: Gender-based communication styles,

just happen; it occurs through acts and A gender analysis of project manage- trust, and satisfaction on virtual teams.

the failures to act by people who run ment guidelines. International Journal Journal of Information, Information

and work for organizations.” of Project Management, 21, 433–441. Technology, and Organizations, 2,

Chapman, R. J. (1998). The effective- 47–60.

Acknowledgment

ness of working group risk identifica- Gale, A., & Cartwright, S. (1995).

The authors wish to thank Dr. Deborah

tion and assessment techniques. Women in project management: Entry

Bloch, professor emeritus in the School

International Journal of Project into a male domain?: A discussion on

of Education at the University of San

Management, 16, 333–344. gender and organizational culture—

Francisco, for her assistance with the

early formation of this research study. ■ Charlesworth, S., & Baird, M. (2007). Part 1. Leadership and Organizational

Getting gender on the agenda: The Development Journal, 16(2), 3–8.

References tale of two organizations. Women in Gibson, C. B., & Cohen, S. G. (2003).

Ali, A. S. B., Anbarri, F. T., & Money, Management Review, 22, 391–404. Virtual teams that work: Creating con-

W. H. (2008). Impact of organizational ditions for virtual team effectiveness.

Cohen, H., & Braford, D. (2005).

and project factors on acceptance and San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Influence without authority (2nd ed.).

usage of project management software

San Francisco, CA: Wiley. Grabher, G. (2004). Architectures of

and perceived project success. Project

Cortesi, G. J. (2001). The relation of project-based learning: Creating and

Management Journal, 39(2), 5–34.

communication channel and task on sedimenting knowledge in project

Ankrah, N. A., Proverbs, D., & Debrah, Y. group composition, participation, and ecologies. Organization Studies, 25,

(2009). Factors influencing the culture performance in virtual organizations. 1491–1514.

of a construction project organization: Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Graham, A. K. (2000). Beyond project

An empirical investigation. Engineering, State University of New York at Albany, management 101: Lessons for manag-

Construction and Architectural Albany, NY. ing large development programs.

Management, 16(1), 26–37. Project Management Journal, 31(4),

Crawford, L., & Pollack, J. (2004). Hard

Bakeman, R., & Robinson, B. F. (1994). and soft projects: A framework for 7–19.

Understanding log-linear analysis with analysis. International Journal of Henderson, L. S. (2008). The impact of

ILOG: An interactive approach. Hillsdale, Project Management, 22, 645–653. project managers’ communication

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. DeSanctis, G., & Monge, P. (1998). competencies: Validation and exten-

Bartol, K. M., Martin, D. C., & Communication processes for virtual sion of a research model for virtuality,

Kromkowski, J. A. (2003). Leadership organizations. Journal of Computer satisfaction, and productivity on proj-

and the glass ceiling: Gender and Mediated Communication, 3(4). ect teams. Project Management

ethnic group influences on leader Retrieved June 21, 2005, from Journal, 39(2), 48–59.

behaviors at middle and executive http://www.asusc.org/jcmc/vol3/issue Hodgson, D. (2002). Disciplining the

managerial levels. Journal of Leadership 4/desanctis.html profession: The case of project man-

and Organization Studies, 9(3), 8–20. Dinsmore, P. C., & Cabanis-Brewin, J. agement. Journal of Management

Berger, J., Webster, M., Jr., Ridgeway, (2006). The AMA handbook of project Studies, 39, 803–821.

C. L., & Rosenholtz, S. J. (1986). Status management (2nd ed.). New York: Hutt, M. D., Stafford, E. R., Walker, B.

cues, expectations, and behaviors. In AMACOM. A., & Reingen, P. H. (2000). Case study:

E. Lawler (Ed.), Advances in group Ely, R. J. (1994). The effects of organi- Defining the social network of a strate-

process (Vol. 3, pp. 1–22). Greenwich, zational demographics and social gic alliance. Sloan Management

CT: JAI Press. identity on relationships among pro- Review, 41(2), 51–63.

Bohlen, G. A., Lee, D. R., & Sweeney, fessional women. Administrative Kanter, R. (1977). Men and women of

P. J. (1998). Why and how project man- Science Quarterly, 39, 203–238. the corporation. New York: Basic Books.

agers attempt to influence their team Eppler, M. J., & Sukowski, O. (2000). Knutson, J. (2001). Succeeding in proj-

members. Engineering Management Managing team knowledge: Core ect-driven organizations. New York:

Journal, 10(4), 21–28. processes, tools and enabling factors. Wiley.

50 December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

Kuehn, U. (2006). Integrated cost and Mills, M. B. (2003). Gender and Rojewski, J. W., & Bakeman, R. (1997).

schedule control in project manage- inequality in the global labor force. Applying log-linear models to the

ment. Vienna, VA: Management Annual Review of Anthropology, 33, study of career development and tran-

Concepts. 41–62. sition of individuals with disabilities.

Lee, D. R., & Bohlen, G. A. (1997). Mulenburg, G. M. (2002). Virtual man- Exceptionality, 7(3), 169–186.

Influence strategies of project man- ufacturing. Journal of Product Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2008).

agers in the information technology Innovation Management, 19(2), Backlash effects for disconfirming gen-

industry. Engineering Management 180–186. der stereotypes in organizations.

Journal, 9(2), 7–14. Neuhauser, C. (2007). Project manager Research in Organizational Behavior,

Lee, D. R., & Sweeney, P. E. (2001). An leadership behaviors and frequency of 28, 61–79.

assessment of influence tactics used by use by female project managers. Project Sahdev, K., Vinnicombe, S., & Tyson, S.

project managers. Engineering Management Journal, 38(1), 21–31. (1999). Downsizing and the changing

Management Journal, 13(2), 16–24. role of human resources. International

Patti, A. L., Gilbert, J. P., & Hartman, S.

Lee-Kelley, L. (2002). Situational lead- (1997). Physical co-location and the Journal of Human Resources

ership: Managing the virtual project success of new product development Management, 10, 906–923.

team. Journal of Management projects. Engineering Management Savicki, V., Kelley, M., & Lingenfelter,

Development, 21, 461–476. Journal, 9(3), 31–37. D. (1996). Gender, group composition,

Lee-Kelley, L. (2006). Locus of control Pendharkar, P. C., & Rodger, J. A. and task type in small task groups

and attitudes to working on virtual (2007). An empirical study of the using computer-mediated communi-

teams. International Journal of Project impact of team size on software devel- cation. Computers in Human Behavior,

Management, 24, 234–243. opment effort. Information Technology 12, 549–565.

Lindgren, M., & Packendorff, J. (2006). Management, 8, 253–262. Schmid, B., & Adams, J. (2008).

What’s new in new forms of organiz- Motivation in project management:

Project Management Institute. (2008).

ing? On the construction of gender in The project manager’s perspective.

A guide to the project management

project-based work. Journal of Project Management Journal, 39(2),

body of knowledge (PMBOK ® guide)—

Management Studies, 43, 841–866. 60–71.

Fourth edition. Newtown Square, PA:

Lu, M., Watson-Manheim, M. B., Author. Sharifi, S., & Pawar, K. S. (2002).

Chudoba, K. M., & Wynn, E. (2006). Virtually co-located product design

Project Management Institute. (2009).

Virtuality and team performance: teams: Sharing teaming experiences

Retrieved August 1, 2009, from

Understanding the impact of variety of after the event? International Journal

http://www.pmi.org/AboutUs/Pages/

practices. Journal of Global of Operations & Production

Default.aspx.

Information Technology Management, Management, 22, 656–679.

9(1), 4–23. Prusak, L., & Cohen, D. (2001). How to

invest in social capital. Harvard Smith, R. A. (2002). Race, gender, and

Martin, J. (2000). Hidden gendered

Business Review, 79(6), 86–92. authority in the workplace: Theory and

assumptions in mainstream organiza-

research. Annual Review of Sociology,

tional theory and research. Journal of Reich, B. H. (2007). Managing knowl-

28, 509–542.

Management Inquiry, 9, 207–216. edge and learning in IT projects: A

conceptual framework and guidelines Stewart, A. J., & McDermott, C. (2004).

Martin, J. (2008). Treacherous terrain:

for practice. Project Management Gender in psychology. Annual Review

Equity and equality at work and at

Journal, 38(2), 5–17. of Psychology, 55, 519–544.

home. Graduate School of Business,

Stanford University. Retrieved Remington, K., & Pollack, J. (2007). Styhe, A., Backman, M., & Borjesson,

December 26, 2008, from http:// Tools for complex projects. Burlington, S. (2005). YCC: A gendered carnival?

www.atn.edu.au/wexdev/local/docs/ VT: Gower. Project work at Volvo Cars. Women in

research//joanne_martin.pdf. Reskin, B. F. (2000). Getting it right: Sex Management Review, 20(1/2), 96–106.

Martins, L. L., Gilson, L. L., & Maynard, and race inequality in work organiza- Thomas, J. L., & Buckle-Henning, P.

M. T. (2004). Virtual teams: What do we tions. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, (2007). Dancing in the white spaces:

know and where do we go from here? 707–709. Exploring gendered assumptions in

Journal of Management, 30, 805–835. Richmond, A., & Skitmore, M. (2006). successful project managers.

McDonough, E. F., III, & Spital, F. C. Stress and coping: A study of project International Journal of Project

(2003). Managing project portfolios. managers in large ICT organizations. Management, 25, 552–559.

Research Technology Management, Project Management Journal, 37(5), Timberlake, S. (2005). Social capital

46(3), 40–46. 5–16. and gender in the workplace. Journal

December 2010 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 51

An Exploratory Study of Gender in Project Management

PAPERS

of Management Development, 24(1/2), Walther, J. B. (1993). Impression devel- research has been published in the Project

34–44. opment in computer-mediated inter- Management Journal, Management