Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Society Role in Preventing Crime

Uploaded by

sunny kumarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Society Role in Preventing Crime

Uploaded by

sunny kumarCopyright:

Available Formats

INTRODUCTION TO THE SPECIAL EDITION

ON EXPERT EVIDENCE

JASON M CHIN * AND CAITLIN GOSS †

We are very pleased to introduce this special issue of The University of Queensland

Law Journal on expert evidence. As many readers will be aware, expert evidence

remains a contentious issue both in Australia and abroad. Questions have been

raised, for instance, about the reliability of many traditional fields of expert

evidence, biases experts may carry with them into court, and the risk of trials

transforming into battles of experts. 1 We hope that this special issue contributes

to the ongoing discussion.

Many people and groups were integral in making this issue possible. First,

we would like to thank the UQ Law, Science and Technology program, which

funded and enabled the colloquia that led to this special issue. 2 As to those events,

we would like to thank the Supreme Court of Queensland for hosting them and the

many speakers and discussants that generously volunteered their time: the Hon

Justice Peter Applegarth, the Hon Justice Soraya Ryan, Kaye Ballantyne, Emma

Cunliffe, Ben Dighton, Rachel Dioso-Villa, David Hamer, Kathryn McMillan QC,

Mehera San Roque and Rachel Searston. We also thank the TC Beirne School of

Law, and Rick Bigwood, Iain Field and the UQLJ, for their generous support.

This special issue begins with David Hamer and Gary Edmond’s ‘Forensic

Science Evidence, Wrongful Convictions and Adversarial Process’, which helps

frame many of the issues herein. 3 This article delves into recent post-conviction

appeals, and in doing so highlights many of the challenges that forensic science

(which is typically adduced by the prosecution) presents in adversarial systems.

*

Sydney Law School; Institute for Globally Distributed Open Research and Education (‘IGDORE’).

†

TC Beirne School of Law, The University of Queensland.

1

See Gary Edmond, ‘Forensic Science Evidence and the Conditions for Rational (Jury) Evaluation’

(2015) 39(1) Melbourne University Law Review 77; Lisa Dufraimont, ‘Regulating Unreliable

Evidence: Can Evidence Rules Guide Juries and Prevent Wrongful Convictions?’ (2008) 33 Queen’s

Law Journal 261.

2

Jason M Chin, ‘UQ Expert Evidence Colloquium 1’, Truth in Evidence (Web Page)

<https://www.jasonmchin.com/jason-chin-evidence-blog/2018/9/5/uq-expert-evidence-

colloquium-aug-30-2018>; Jason M Chin, ‘UQ Expert Evidence Colloquium 2’, Truth in Evidence

(Web Page) <https://www.jasonmchin.com/jason-chin-evidence-blog/2019/2/18/uq-expert-

evidence-colloquium-pt-2-february-12-2019>.

3

David Hamer and Gary Edmond, ‘Forensic Science Evidence, Wrongful Convictions and the

Adversarial Process’ (2019) 38(2) University of Queensland Law Journal 185.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3546858

184 Introduction 2019

Another such challenge is highlighted in Searston and Chin’s article, which

suggests that some forms of forensic expertise are primarily subjective, intuitive

judgements of the practitioner, which makes them difficult to explain and cross-

examine. 4 In the following article, Smith and Thompson argue that an important

step for many forensic practices — and one that may assuage some concerns

about them being subjective and intuitive — is testing experts’ claims. 5 Smith and

Thompson find that many fields still have work to do in delineating testable

claims. McKimmie and colleagues then discuss another fundamental issue in

expert evidence: gender biases that may impact how the trier of fact assesses the

evidence. 6 They find some evidence for such bias in an original empirical study.

The remainder of the special issue goes on to discuss specific topics of expert

evidence. Gary Edmond explores the history of fingerprint analysis in Australian

courts and finds — troublingly — that it has almost never been challenged on

epistemic grounds. 7 Monds and colleagues discuss the complex and fraught issue

of police serving as ‘experts’ when assessing whether an individual is intoxicated

through exposure to drugs or alcohol. 8 They find that legislation governing such

practices is underdeveloped, and that further research is needed into police

training and how police go about making judgements of intoxication. Finally,

McMillan and Pokarier consider social scientific expert evidence and tzhe various

ways in which such evidence is introduced into court. 9

4

Rachel A Searston and Jason M Chin, ‘The Legal and Scientific Challenge of Black Box Expertise’

(2019) 38(2) University of Queensland Law Journal 237.

5

Chloe A Smith and Matthew B Thompson, ‘Performance Claims in Forensic Science Expert Opinion

Evidence’ (2019) 38(2) University of Queensland Law Journal 261.

6

Blake M McKimmie et al, ‘The Impact of Gender-Role Congruence on the Persuasiveness of Expert

Testimony’ (2019) 38(2) University of Queensland Law Journal 279.

7

Gary Edmond, ‘Latent Science: A History of Challenges to Fingerprint Evidence in Australia’ (2019)

38(2) University of Queensland Law Journal 301.

8

Lauren A Monds et al, ‘Police as Experts in the Detection of Alcohol and Other Drug Intoxication: A

Review of the Scientific Evidence within the Australian Legal Context’ (2019) 38(2) University of

Queensland Law Journal 367.

9

Kathryn McMillan and Nicholas Pokarier, ‘Beyond Common Knowledge: Reviewing the Use of

Social Science Evidence in Australian Courts’ (2019) 38(1) University of Queensland Law Journal 389.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3546858

You might also like

- So Good They Cant Ignore You by Cal Newport Book Summary and PDF 1 PDFDocument8 pagesSo Good They Cant Ignore You by Cal Newport Book Summary and PDF 1 PDFAimee Hall100% (1)

- Commercial InvoiceDocument1 pageCommercial InvoiceAli SadegaNo ratings yet

- Acrostic Poem Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesAcrostic Poem Lesson Planapi-306040952No ratings yet

- Top 100 Cities 2019Document33 pagesTop 100 Cities 2019Tatiana Rokou100% (1)

- Procedural Fairness, The Criminal Trial and Forensic Science and MedicineDocument36 pagesProcedural Fairness, The Criminal Trial and Forensic Science and MedicineCandy ChungNo ratings yet

- Offender ProfillingDocument192 pagesOffender Profillingcriminalistacris100% (3)

- Probability and Statistics in Criminal ProceedingsDocument122 pagesProbability and Statistics in Criminal ProceedingsvthiseasNo ratings yet

- Forensic Fraud: Evaluating Law Enforcement and Forensic Science Cultures in the Context of Examiner MisconductFrom EverandForensic Fraud: Evaluating Law Enforcement and Forensic Science Cultures in the Context of Examiner MisconductRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Impact of Globalisation On Judicial ProcessDocument21 pagesImpact of Globalisation On Judicial Processsunny kumarNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalisation On Judicial ProcessDocument21 pagesImpact of Globalisation On Judicial Processsunny kumarNo ratings yet

- The Psychology and Sociology of Wrongful Convictions: Forensic Science ReformFrom EverandThe Psychology and Sociology of Wrongful Convictions: Forensic Science ReformWendy J KoenNo ratings yet

- Writing Law Dissertations - An Introduction and Guide To The Conduct of Legal ResearchDocument257 pagesWriting Law Dissertations - An Introduction and Guide To The Conduct of Legal ResearchBALtrans100% (4)

- Forensic Science in Canada PDFDocument114 pagesForensic Science in Canada PDFTristanBruceNo ratings yet

- India A Good Venue For ArbitrationDocument13 pagesIndia A Good Venue For Arbitrationsunny kumarNo ratings yet

- Project Office ChecklistDocument6 pagesProject Office Checklistdagomez2013No ratings yet

- Questioned Documents Report 454Document10 pagesQuestioned Documents Report 454rotsacreijav77777No ratings yet

- El Mejor Seguro Contra Los Errores Judiciales Causados Por La Ciencia Basura Una Prueba de Admisibilidad Científica y Legalmente Sólida. ImwinkelriedDocument25 pagesEl Mejor Seguro Contra Los Errores Judiciales Causados Por La Ciencia Basura Una Prueba de Admisibilidad Científica y Legalmente Sólida. ImwinkelriedZigor PelaezNo ratings yet

- Ipda Journal Vol 11 - 1-12Document37 pagesIpda Journal Vol 11 - 1-12ronan.villagonzaloNo ratings yet

- Edmond - ContextualDocument69 pagesEdmond - ContextualFernando SilvaNo ratings yet

- Scientific and Legal Developments in Fire and Arson Investigation by Rachel Dioso-Villa MN Journal Law Science Tech Issue 14-2Document32 pagesScientific and Legal Developments in Fire and Arson Investigation by Rachel Dioso-Villa MN Journal Law Science Tech Issue 14-2Sabeena NaseerNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Forensic Science in The United States: A Path ForwardDocument12 pagesStrengthening Forensic Science in The United States: A Path Forwardchrisr310No ratings yet

- 38 - 1 - 4neg Unimelb PDFDocument47 pages38 - 1 - 4neg Unimelb PDFIjibotaNo ratings yet

- Forensic Science in CanadaDocument114 pagesForensic Science in CanadaJulián EspinalNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography The World of Forensic ScienceDocument14 pagesAnnotated Bibliography The World of Forensic Scienceapi-301806252No ratings yet

- evidance Act HDocument9 pagesevidance Act Hward fiveNo ratings yet

- The Googling JurorDocument54 pagesThe Googling JurorDavid Harvey100% (4)

- The Individualization Fallacy in Forensic Science EvidenceDocument23 pagesThe Individualization Fallacy in Forensic Science EvidenceShweta KumariNo ratings yet

- Stephen Lawrence 25 Years On: Homicide Professionalism and Decision-Making by SIOs in The Modern Era During Austerity'Document87 pagesStephen Lawrence 25 Years On: Homicide Professionalism and Decision-Making by SIOs in The Modern Era During Austerity'Rena Jocelle NalzaroNo ratings yet

- Case Studies Reveal Broader Perspectives on Pre-Trial PublicityDocument34 pagesCase Studies Reveal Broader Perspectives on Pre-Trial Publicitymariam machaidzeNo ratings yet

- Case Studies of Pre - and Mid-Trial Prejudice in Criminal and CiviDocument54 pagesCase Studies of Pre - and Mid-Trial Prejudice in Criminal and CiviLatika RawlaniNo ratings yet

- Advanced Evidence Law, Course OutlinesDocument8 pagesAdvanced Evidence Law, Course Outlineshritik.kashyap23No ratings yet

- Comparative StudyDocument15 pagesComparative Studyshahdishaa988No ratings yet

- MatthewBThompson Tangen McCarthy EvidenceForExpertiseInFingerprintIdentification AAFS2013 Abstract v03Document1 pageMatthewBThompson Tangen McCarthy EvidenceForExpertiseInFingerprintIdentification AAFS2013 Abstract v03MichelangeloNo ratings yet

- Judicial Gatekeeping of Scientific Evidence and Experts in Criminal AdjudicationsDocument29 pagesJudicial Gatekeeping of Scientific Evidence and Experts in Criminal AdjudicationshidhaabdurazackNo ratings yet

- Ideology or Situation Sense - An Experimental Investigation oDocument93 pagesIdeology or Situation Sense - An Experimental Investigation oAhmed SaidNo ratings yet

- The Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision - Findley e ScottDocument108 pagesThe Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision - Findley e ScottPedro Ivo De Moura TellesNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Judicial System in England and WalesDocument17 pagesUnderstanding the Judicial System in England and WalesDivyansh MimrotNo ratings yet

- Regulating Flawed Bite Mark EvidenceDocument54 pagesRegulating Flawed Bite Mark Evidencerobsonconlaw100% (1)

- 9781315094205_previewpdfDocument89 pages9781315094205_previewpdfnicoledanielatgNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Expert Opinion Evidence: Melbourne University Law Review May 2017Document33 pagesRethinking Expert Opinion Evidence: Melbourne University Law Review May 2017vijay srinivasNo ratings yet

- Police Survey Ms 07Document20 pagesPolice Survey Ms 07kristine joy piterosNo ratings yet

- Thesis - Rape Trial Court Experiences PDFDocument99 pagesThesis - Rape Trial Court Experiences PDFarjoshNo ratings yet

- INTERPOL 18th IFSMS Review Papers-2016Document769 pagesINTERPOL 18th IFSMS Review Papers-2016habtamu tsegayeNo ratings yet

- Empirical Study of Insider Witnesses' Assessments at The International Criminal CourtDocument30 pagesEmpirical Study of Insider Witnesses' Assessments at The International Criminal CourtJuana LoboNo ratings yet

- Cornell Law Review ArticleDocument30 pagesCornell Law Review Articlepalmite9No ratings yet

- (Australia) Law and Norm. Justice Administration and The Human Sciences in Early Juvenile Justice in VictoriaDocument28 pages(Australia) Law and Norm. Justice Administration and The Human Sciences in Early Juvenile Justice in VictoriaTrần Hà AnhNo ratings yet

- Invalid Forensic Science Testimony and Wrongful ConvictionsDocument97 pagesInvalid Forensic Science Testimony and Wrongful ConvictionsTlecoz Huitzil100% (1)

- 2430 Foreword-SentencingPrinciples PDFDocument7 pages2430 Foreword-SentencingPrinciples PDFchalacosoyNo ratings yet

- Reliability of Expert Evidence Key to International DisputesDocument62 pagesReliability of Expert Evidence Key to International DisputesMian Sami ud DinNo ratings yet

- Avoiding The Perfect Storm of Juror Contempt: Professor Cheryl ThomasDocument21 pagesAvoiding The Perfect Storm of Juror Contempt: Professor Cheryl ThomasRedMachaNo ratings yet

- Modern Scientific Techniques Help Achieve Fair Criminal JusticeDocument18 pagesModern Scientific Techniques Help Achieve Fair Criminal JusticeSam OndhzNo ratings yet

- Bschmidt - Pride - Final Draft 1Document15 pagesBschmidt - Pride - Final Draft 1api-480331204No ratings yet

- Criminal Investigation Research Paper IdeasDocument7 pagesCriminal Investigation Research Paper Ideasgw060qpy100% (1)

- Judicial Officers Bulletin The Courts and Social MediaDocument6 pagesJudicial Officers Bulletin The Courts and Social MediaYo Boi KatakuriNo ratings yet

- Schweitzer & Saks (2007) CSI EffectDocument9 pagesSchweitzer & Saks (2007) CSI EffectEden SkyeNo ratings yet

- Improving Forensic Science Reliability in Indian Criminal Justice System: An Empirical StudyDocument10 pagesImproving Forensic Science Reliability in Indian Criminal Justice System: An Empirical StudyAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Contention One Is Inherency:: Fundamental ClashDocument4 pagesContention One Is Inherency:: Fundamental ClashmatthewleedavisNo ratings yet

- Making Human Dignity Central to International Human Rights Law: A Critical Legal ArgumentFrom EverandMaking Human Dignity Central to International Human Rights Law: A Critical Legal ArgumentNo ratings yet

- Informative SpeechDocument7 pagesInformative Speechapi-340376954No ratings yet

- M. Pardo - The Field of Evidence and The Field of KnowledgeDocument72 pagesM. Pardo - The Field of Evidence and The Field of KnowledgeGonçaloBargadoNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Cotton - When Judges Dont Follow The Law - Research and Recommendations - 35Document35 pages2015 - Cotton - When Judges Dont Follow The Law - Research and Recommendations - 35Fernando Silva100% (1)

- The Effect of Human Rights On Criminal ProcessDocument29 pagesThe Effect of Human Rights On Criminal Processqian linNo ratings yet

- The Supreme Court, The Media, and Public Opinion: Comparing Experimental and Observational MethodsDocument49 pagesThe Supreme Court, The Media, and Public Opinion: Comparing Experimental and Observational MethodsPrafull SaranNo ratings yet

- Epistemology and Evidence Law Course GuideDocument8 pagesEpistemology and Evidence Law Course GuideSundus DaniyalNo ratings yet

- Court Party ThesisDocument5 pagesCourt Party Thesisangelagibbsdurham100% (2)

- How To Write A Research Paper On Forensic ScienceDocument5 pagesHow To Write A Research Paper On Forensic ScienceaflbrtdarNo ratings yet

- Best Practice Recommendations For Eyewitness Evidence Procedures: New Ideas For The Oldest Way To Solve A CaseDocument36 pagesBest Practice Recommendations For Eyewitness Evidence Procedures: New Ideas For The Oldest Way To Solve A Caseapi-61200414No ratings yet

- THDC ENGINEERS AND LAWYERSDocument7 pagesTHDC ENGINEERS AND LAWYERSPankaj KumarNo ratings yet

- Chandigarh 18022022Document1 pageChandigarh 18022022sunny kumarNo ratings yet

- Chennai18022022 ADocument1 pageChennai18022022 Asunny kumarNo ratings yet

- UGC-NET-DECEMBER-2020 - JUNE-2021-SUBJECT - CATEGORY-MarksDocument39 pagesUGC-NET-DECEMBER-2020 - JUNE-2021-SUBJECT - CATEGORY-Markssunny kumarNo ratings yet

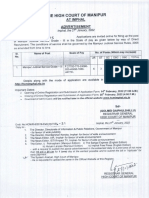

- THE Manipur: High Court ofDocument5 pagesTHE Manipur: High Court ofsunny kumarNo ratings yet

- Advertisement of Job and It's ImportanceDocument6 pagesAdvertisement of Job and It's Importancesunny kumarNo ratings yet

- Role of Public in Crime PreventionDocument1 pageRole of Public in Crime PreventionLilNo ratings yet

- Africa-Ethnic-Religious-Groups PPDocument14 pagesAfrica-Ethnic-Religious-Groups PPPaul MoldovanNo ratings yet

- C4. Layout StrategyDocument23 pagesC4. Layout StrategyÁi Mỹ DuyênNo ratings yet

- Hammond Magic PDFDocument9 pagesHammond Magic PDFJaney BurtonNo ratings yet

- Test de Exersare Nr. 1 Engleză 2020Document6 pagesTest de Exersare Nr. 1 Engleză 2020Janetz KrinuNo ratings yet

- Laguna TourismDocument6 pagesLaguna TourismRennee Son BancudNo ratings yet

- Module 3Document6 pagesModule 3Sherica PacyayaNo ratings yet

- ArbitrationDocument4 pagesArbitrationjuhi biswasNo ratings yet

- Civil Rights Movement StoryboardDocument2 pagesCivil Rights Movement Storyboardapi-324501629No ratings yet

- Theories of Punishment and Punishment Under IpcDocument12 pagesTheories of Punishment and Punishment Under IpcNisha SinghNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in MapehDocument4 pagesLesson Plan in MapehJesseNo ratings yet

- Webinar Strategy TemplateDocument9 pagesWebinar Strategy TemplateDr. Abhijeett DesaiNo ratings yet

- Paro - Ecocity of BhutanDocument15 pagesParo - Ecocity of BhutanTanaya VankudreNo ratings yet

- Name: Sufiya Nurul Indah NIM: 2520160036 MK: Translated (Ptei)Document3 pagesName: Sufiya Nurul Indah NIM: 2520160036 MK: Translated (Ptei)Sofia IndahNo ratings yet

- Vulnerability Management Guideline v1.0.0 PUBLISHEDDocument11 pagesVulnerability Management Guideline v1.0.0 PUBLISHEDJean Dumas MauriceNo ratings yet

- Controlled Student RecordsDocument2 pagesControlled Student RecordsLEEWIN GOYAONo ratings yet

- Community Health Action Project PlanDocument1 pageCommunity Health Action Project PlanJulius BayagaNo ratings yet

- TRAI Mobile VAS Comments From StakeholdersDocument83 pagesTRAI Mobile VAS Comments From Stakeholdersmixedbag100% (1)

- Pakistan Studies - Lecture 1Document7 pagesPakistan Studies - Lecture 1Muhammad Muzammil Bin AtaNo ratings yet

- YSJ Programmes BrochureDocument32 pagesYSJ Programmes BrochureAshish GejoNo ratings yet

- NIT Calicut BTech CSE CurriculumDocument14 pagesNIT Calicut BTech CSE CurriculumNithish Sharavanan SKNo ratings yet

- Marie Chris B. Ramoya: Curriculum Vitae for Philosophy Instructor and ResearcherDocument5 pagesMarie Chris B. Ramoya: Curriculum Vitae for Philosophy Instructor and ResearcherChristine Aev OlasaNo ratings yet

- Top 350 MCQ PomDocument91 pagesTop 350 MCQ PomjaivikNo ratings yet

- GTU Exam Questions on Engineering Economics and ManagementDocument18 pagesGTU Exam Questions on Engineering Economics and ManagementHrishikesh Bhavsar100% (1)

- Developing Writing Material by Using Blended Learning in Vocational High SchoolDocument10 pagesDeveloping Writing Material by Using Blended Learning in Vocational High Schoolrizka widayaniNo ratings yet

- Regularizing Assistant Surgeons in Tamil NaduDocument3 pagesRegularizing Assistant Surgeons in Tamil NaduVasanth DocuNo ratings yet