Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Leisner-Jensen, M. (2002) Vis Comica Consummated Rape in Greek and Roman New Comedy

Leisner-Jensen, M. (2002) Vis Comica Consummated Rape in Greek and Roman New Comedy

Uploaded by

Enzo Diolaiti0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views15 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views15 pagesLeisner-Jensen, M. (2002) Vis Comica Consummated Rape in Greek and Roman New Comedy

Leisner-Jensen, M. (2002) Vis Comica Consummated Rape in Greek and Roman New Comedy

Uploaded by

Enzo DiolaitiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

snr ge sort cette revue sont Tanghs,Yallemand et Ie Franca la

icles est de 50 pages imprimées.

ia rédaction doivent étre produits électronique

jours chez eux une copic du manuscrt.

saccommoder aux principes suivis

Les langues do

Jongueur maxi

Tes manuscrits 5

ment, Les auteurs garderont tou}

‘Quant ae ciarions des tents anciens

dace Geek Engh Lexicon de Liddell Sco Jones et dans Ne Thesaurus Lin

quae Latinge respectivement

Tes références aux cEuves

montrent les exemples que voick :

jum des art

«s modernes doivent érre formulées comme le

Monographies

Oliver (ou bien

Exits and Entrances in Greek

0.) Taplin The Sager of Ascyls. The Dramatic Ue af

Fiagedy (Oxford 1977) 242-451 25

is ‘Quincey RAM 120 (1977) 14-43, bien:

J H.Quineey "Textual Notes on Aeschylus Choephori” Rh 120 (1977) 3

4%.

Uae les abréviations employées dans LAnnée Philolegique

‘Adeesser les manusctits &

CLASSICA ET MEDIAEVALIA

Université Aarhus

Instieur des études anci

B 414, Nar. Ringgade,

jennes et médigvales

ppx-Bo00 Aarhus C

Danemark

E-mail: classica@au.dke

Tnternet: wwwau.dkiclassica

Fax, +45 8942 2050

ninisertion et es souscriptions &

munications concernant l'adm

‘dela série Clasica et Mediacvalial!

Toutes les com

Mediaevala et aux owrages

Jarevue Clasca et

Disertationes doivent etre envoyées i

MUSEUM TUSCULANUM PRESS

University of Copenhagen

Nijalagade 92 + 9K-2300 Copenbagen S « Denmark

Fax og 3532 91133 -order@mip.dk - womep.dk

ANICA INDAGATIONIS ANTIQVITATIS ET MEDUAEYE

. | yauo4l?

CLASSICA

ET MEDIAEVALIA

Revue danoise de philologie et d histoire

Tonnes Bekiker-Nieken - Jesper Carlsen

Karsten Friis Jensen - Vincent Gabrielen

Minna Skafie Jensen - Birger Munk Oken

Ole Thomsen

VOL. 53

CASSICA ET MEDIAEVALIA VOL. 53 TABLE DES MATIERES

Cope © Miscum Taculanam Prs 000

Ses by es Ren Poe

‘ted in Dena by Special Teves Vibog +

STUART LAWRENCE

pans 7a 4 Homeric Deliberations and the Gods

PERNILLE FLENSTED-JENSEN

publi abvenionnde pa Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed:

te Conse de recherche des The Odysey and O Brother Where Art Th01? sons 5

secs cence umsines de Dara

ADAM SCHWARTZ,

ube wih de saporof ‘The Early Hoplite Phalanx: Order or Disarray?..ssninnnnnnnsen SE

Te Dash Reach Couns FA oe

forthe Haier On the Gortynian ITAA and 2TAPTOS of the sth Century

65

ANDERS HOLM RASMUSSEN

‘Thucydides’ Conception of the Peloponnesian War Il: Hell. ruecrssn Bt

(CHRISTOS ©. TSAGALIS

Xenophon Homericus: An Unnoticed Loan from the Iliad

in Xenophon’s Anabasis 3 101

CHRISTIAN GOBEL

‘Megarisches Denken und seine ethische Relevant snnnnnnnninnneI33

IOANNNIS M. KONSTANTAKOS

‘Towards a Literary History of Comic Love..nnnmnnnnnnnnennnne Eh

MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

Vis comica: Consummated Rape in Greek and Roman

New Comedy

VavOS LIAPIS

Notes on Menandri Sententiae

97

MUSEUM TUSCULANUM PRESS

TONNES BEKKER-NIFLSEN

Uvesof Copeagen :

Nie 2 ‘Nets, Boats and Fishing in the Roman World sen IS

350 CopentagenS oe

Tas 929109 Jupiter Latiaris and Human Blood: Fact of Fiction? onennnsnnn 23$

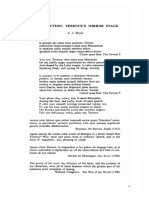

VIS COMICA:

CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK

AND ROMAN NEW COMEDY"

dy Mogens Leiner Jensen

Summary All examples of consummated rape in the comedies of Menande, Plas, and

Terence ae listed and commented upon. As fat as ape is concerned, comedy should not be

taken as miroring reality. Rape on che comic stage was mainly a convenient convention,

Everybody knows that a large part of the plots of the newer Greek and the

Roman comedies are tailored to one pattern, namely ‘boy meets git!’ and

what follows: in spite of the resistance on the part of their surroundings, es-

pecially their fathers, but assisted by faithful servants, they — and we ~ inevi-

tably arrive ata happy ending. On this pattern one can, according to taste or

purpose, construct a comedy of character, manners, or intrigue, a farce or a

moral comedy.

To a love-story of this kind necessarily belongs an account of the way and

the circumstances under which the two young people did originally mect.

‘Their first encounter is never shown on stage, as far as T know. It is revealed

in the prologue or narrated by one of the characters. In one case the encoun-

ter takes place during the comedy but behind the stage, the Fienuchus of

and, presumably, in his model, Menander's Bunuchos. As literature,

drama, film show — not to speak of everyday experience ~ the ways and

means of Cupid are numerous, or rather innumerable, But an astounding

number of comedies have the same beginning of the love-story, namely @

consummated rape: during a festival for instance, at night, under the influ-

cence of wine a young man assaults a young maid and makes her pregnant. In

due time the child is bora, often while the comedy is playing (in the Eunuch

Terens

1 Quotations in this paper are from Amocts Loch Menand, and Emnouts and Ma-

rouzcaus Budé es. of resp. Plutus and Terence. Translations are mine, if not otherwise

seated,

Mogens Lee Jen Vis oni: Connie Rape in reed Roman New Cad? GBM 9 (10001

174 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

even the rape takes place during the play: likewise behind the stage). That a

rape could not be staged in modern times, not even behind the stage, when

the church, cither the Roman or the Lutheran or Reformed one, domi-

neered society, stands to reason, But how is it that a consummated rape

could at all appear in Greek plays meant for a laughter-provoking pastime?

A rape isa tragical and fatal experience to the victim and a setious criminal

offence. Could it be different to the citizens of fourth-centuty Athens? Icis

hardly probable, In some comedies we are not left jm doube chat the girl had

remonstrated vigorously and was left in a deplorable state, and the raper is

well aware that what he has done was an outrage against the girl In this pa-

per I shall examine the circumstances of the rapes in the various comedies

Answers to the questions of how, how many, when and where may, I hope,

throw some light on the problem.

In che following sections I shall comment on the eases of rape known to me

in the new Greck and Latin comedies. One can reasonably suppose a priori

that not only Menander, Plautus, and Terence employed this special feature,

and chat supplementary material could be found in the voluminous collec.

tions of fragments of the other comic poets. We can in fact conclude from

the comedies investigated that other poets had rapes too in their plays. Buc I

incline to believe that the three of whom we have sufficiently connected

texts, will suffice for the purpose, viz. to obtain an answer to the question

here posed, i.e. how could 2 serious criminal offence be shown to be the

starting point ofa love-story with a happy ending?

In whae follows I shall limit myself to mentioning or quoting words and

lines which indicate a rape, and what can be seen or concluded about the

circumstances of the event. Detailed synopses are hardly relevant in this

connection.

2 and Roman, But as the ape is transferred from the Gree, ie. Ac, comedies, any ex

planation must be found in Athens. The Romans may have shrugged oe despised the

Greek morer= those Grecks!~ and after ll have amused themselves. In one case, the Epi

tows, Plas seems co have thrown a veil over a appy ending which might have been

‘unacceptable toa Roman audience,

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK... 175

MENANDERS

In the Georgos “The Farmer'4 a young man (name unknown) has made a

young girl pregnant,> possibly because he is in love with her and hopes to

marty her, so that it may be rather a case of intercourse before the marriage

(if that makes a difference). The complications begin when the young man's

relatives arrange another marriage. Myrchine, the mother of the girl, has also

a son but a husband is not mentioned. Ie is just a possibility chat she herself

had been raped in her youth, so that the father will also be duly found in the

course of the comedy.

Epitrepontes ‘Men at Arbitration. Shortly after his marriage with Pamphile

Charisios sets out for a business trip. At his return Onesimos, his slave, blabs

cout that Pamphile five months after the marriage has given birth to a boy,

who has been discretely removed. Charisios immediately leaves their home,

although, or because he is deeply in love with his wife as she isin him. But it

is discovered thatthe child had been conceived during the Tauropolia at Ha-

lai, and that the guilty man was Charisios himself when drunk. An eye-

witness, a fluteplayer called Habrotonon, tells

Habrotonon

dnhadiy

-ponninas mazatoioas wivas

bvémene kod vio nacoions eyévero

-rowtirov Erepov. (473-6)

Habrovonon

ob of. éhaviin rio web) yu ob" exe,

3 sow Ava clas to W.G. Arnos Lach Menanet vl Cambridge Mans/London (1979)

vol 3 (196); vol. 3 (200; Sand. Cimon to Menender A Commentary by AW, Grmme snd

FH, Sandbach, Oxford (1973) K-Th. to Aled Koercs nd Andes Thiers Teubner

ce. (1953 ante.

4 Atm 1, 1B 30587 (107 fg 4) and 9e 3 (p36) Arm Se aio Amoe’s

otc. 04. ~ Actual he tiles ofthe play arent relevant oor concen

5 e113} 30, Phila the maid or old nse of Metine wo her misces: awe | 6 woes

tg ibn nwt shat sum to contact a mariage, afer he's eine ou gil?”

(ce Norma Miler, Mander, Pls and Fragmens, enguin Books (1987) 187. Fg. 2

‘Arn 1 p 128: 33 Boothe wrongdoer. The bith probably aes place dung the

play

176 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

ee Baring wéovoa neooroecer win,

rinhove’ éauriig ths Tpigas, xahéy md

al Derrréy, & Boi, raparivey agiidoa.

drnohushensi’» Shov vite éeyére1 fiaos. (486-90)

Habrotonon

[ suppose he came actoss the woman during the night-festival and

unprotected. You know, something very like that actually happened in my

presence.

Habrotonon

1 don’ know. But she was with us, then she wandered off, then suddenly

ran up on her own, crying and tearing her hait. And her silky wrap, very

thin and_precey, was quite ruined, all corn to pieces,

(ct Milles. 5 above, p. 92 £. with slight alterations)

Everything is elucidated and the comedy ends merrily

Fabula incerta.® "To the famous papyrus-codex in Cairo belong some

scraps which have made it possible to reconstruct (with lacunae) one page,

ww. 252 and 33-64, of a comedy, the title of which is still unknown. The

characters appearing are Laches, an elderly man, his son Moschion,

Chaireas, a young friend of Moschion, and Kleainetos, another elderly gen-

tleman, possibly an Arcopagite. Apparently Moschion has ‘raped’ Kleainetos

daughter, and honourably married her during his father’ absence on a very

long business-tip. After Laches! return i is material that he should accept

the marriage, and in the preserved about 60 verses it seems that Chaireas (or

a slave) has concocted a plan to explain and so obtain the paternal consent

to the match, and at the same time his acceptance of Chaireas as his son-in-

law, We are evidently at a fairly advanced stage of the plot. It contains both

Chaireas’ attempt to convince Laches of his fictional story, and Kleainetos

attempe to explain co Laches that everything isin perfect order, that he him-

self has acquiesced and welcomed Moschion as his son-in-law, and that a

boy has already been born!

6 In Am 3 itis Fab. ne 1 pp 426-72

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GRERK ... 177

Vz 17 has éSeipriaro ‘he accomplished, perpetrated’ (ep. Epitrepontes 895

about the same offence).”

Chaireas

fixove dy; wou. Moorziaw ry racbevoy

Chaisv ter, Kaeaiverde). (27 £)

Kleainetos

indueba yaderavely a€ voir0 nUbuevoy. (46-8)

Chaireas

Listen to me. Kleainetos, the gitl was seized by Moschion, he's got her.

Kleainctos

We settled that, though, long ago. Your Moschion has got the girl. He

took her willingly, not by duress. We thought youll be upset when you

found out.

(ce. Arnott 3, 439 and 443)

Whether Kleainetos speech means that Moschion had not raped the girl, or

ic is parc of the plan in order to make Laches swallow che pill les reluctantly,

ic at all events refers to a consummated rape as part and parcel of what is to

be expected from a love-story on the stage. Laches is understandably enough

bewildered, and only wants to scream (¥. 64). As for a discussion and incer-

pretation of these somewhat complicated proceedings I refer the reader to

Arnott’ detailed exposition (Le. 427-30).

Heros “The Guardian Spirit’. Eighteen years ago (frg. 70, 94, Am. 2, 34)

Myrrhine, then a virgin (Arg. 1, Arn., ibid. 8), has been ravished by Laches

and given birth to twins (arg. 1-3; fig. Bef recto 79, ibid. 32). She gave them

10 Tibeios, a shepherd to reat. Their names are Gorgias and Plangon. She has

afterwards married Laches, the raper, without their recognizing one another.

17 Sandbach Comm. 686. Amote considers ic a euphemism: He (se. Chaies] shies off rom

saying openly that Moschion raped Klesinetor daughter Lc, 4352 5,

178 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

In the scene where Myrrine reveals her past ro Laches, now her husband, the

latter, understandably enough, says:

tioadis 3 nefiqua yoerai, nis haBiver

a mooomentin ae; nis athe: (fr 70 96-7, Arn. ibid. 34)

The puzzle’ worse now. How did this assailant avoid your seeing him?

How did he leave you? (tr. Ar, ibid. 35)

‘A question, which also puzzles us, and of which he ought to know the an-

swer. Plangon in her turn has now been raped by Pheidias, a neighbour (arg

6 Fs peizwy 36 1g | neomBucner wera Sr Ty weloaxa.‘A neighbour had pre-

viously forced the maid’; tz Arn. 2, 9) and has born a child. The rapes in the

two generations are cleared up, and Pheidias (62° nuenxtis ‘the wrongdoer)

‘can marry Plangon, she being the daughter of an Artic citizen (Arg. 10-2).

Kisharstes “The Lyre Player. A mutilaced scrap of a papyrus in Berlin

which contains the ends of 27 lines of this comedy has the words oer 76

‘peqovdg ‘what happened by violence’ (I. 19) and Bias ‘by force’ (20) (Arn. 2,

18)

Plokion “The Necklace.® We owe our knowledge of this comedy primarily

to Aulus Gellius, who in the Noctes Atticae 2.25 compares it with Plocium,

the adaptation by Caccilius Seatius. Gellius gives this synopsis:

Filia hominis pauperis in pervigili vtiata ex. Eaves clam pasrem fit,

Ihabebatur pro vingine, Ex co vitio gravida mensibus exactis parturit, Serous

bonae frugi, cum pro foribus domus staret et propinguare partum filiae atque

omnia vitinon ese oblasum ignonart, gemitum et ploratum puellae audit in

puerperioenitentis: times, irascitur, suspicarur, dolet, (SS 15-18)

‘The daughter of a poor man was raped during an all-night festival. This

was kept secret from her fathers, and she was believed ro be a virgin. Be-

cause of this sinful act, when her time came, the pains set in. An honest

slave, standing outside the house doors, who did not know that the daugh-

§ Not in Am. its not sated why. The longer fragments ~ from Gellius and Seobaios — are

found in Sandbach, OCT Menander (1972 and 1990): 3-4 se also Sandb. Comm. 705

They are translated by Miller (a. 5) 240-2 They do not mention the rape,

vis Comic,

ONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK... 179)

ters delivery was approaching, or that she had been the victim of an out

rage, hears the girl groaning and crying in labour: he is caught by fear, ex-

asperation, suspicion, and grief,

Samia “The Gitl from Samos’. Moschion, the young and naive hero of the

play, relates in the prologue, without disguising anything, what has hap-

pened so far: during the celebration of mourning for Adonis he has been

drunk and violated Plangon, the daughter of his nabour Nikeratos. He im-

mediately confessed his guilt to the girl’s mother and vowed to marry het

daughter. The child has already been born (wv. 38-56). It is reasonable to

suppose that he was already in love with the girl next door, so that itis inter-

course before the marriage. But Demeas, his adoptive father, and Nikeratos

during a long business trip to Byzantion that they undertook together, have

reached the agreement that the two young people are to be martied. And so

they are, afer many complications, most happily.

‘Synaristosai ‘Women Lunching Together’. One fragment of this comedy is

a quotation from a treatise iced On Interpretation, attributed to the theto-

rician Hermogenes.? The lines from Menander correspond closely to lines

89-92 of Plautus’ Cistellara.

ribopérou yi Twos nipns, nis en BedBacuern, ceunids adbyyiaTo

noiqun ailrcoiy dria Bedriorag

: Avoroaioy 7h He

royemy.

6.28 w nohosOnoer weer 00 mode ny Blea”

Enerra dorriov kai xohaxetn éué ve Kai

viv ware’ By ude) — (Arn, fr. 1344)

For there, when someone asked a girl how she had been sexually as-

saulted, she described a disgusting evene with dignity by using the most

choice vocabulary: For the Dionysia had a procession'® ...]. He followed

9 Bd, H.Rabe (1913), p. 200. Fg. 382 K-Th,, Arm 51344

ro Acconding to Pausanias (2.75) once 2 year a night (N.B.), images of Dionysus wete

brought to the sanctuary from che sovaled Kooneerian, with torches butning and

hymns

180 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

ime right to the door, and then, with always dropping in and flattering me

and my mothes, he got to know me (er. Arn, ibid., 345 slightly altered).

For a mote details see below under Plautus,

‘Phasma “The Apparition.” Few fragments of this comedy have been pre-

served. Donatus in his commentary on Terence’s Eunuchus (prol. 9.3 printed

Arn. 3, 406-9) gives a synopsis of the Phasma containing only the initial

situation, From this it is seen that the mother of the young girl was born

after a consummated rape:

Phasma autem nomen fabulae Menandri est, in gua noverca superducta

sadulescentivirginem, quam ex vitio quondam conceperat, furtim eductam

[-l Pabebat

“The Apparition’, however, is che title of a play by Menander. In it a

young man acquired a stepmother who had formerly been raped, con-

ceived a daughter and brought her up secretly. (Arn. 3, 406 ft. Arn.)

In a dialogue between a man and a woman (t93-207) the woman relates a

raping at Brauron which is too damaged to be quoted here (Arn. 3, 398, ll

203-7), but itis quite evident that she describes a story very similar co what

Habrotonon in Epitrepontes tells about Pamphile’s shocking experience at

the Tauropolion. Some words are used in both comedies: Phasma 195 nav=

ugibos obtens Epim. 452 reaywyidog obeys: Phasma 199 mhaynfieion Epitr. 486

éxAavif, Ics probably the same rape as that mentioned by Donatus.

Pap. Antinoopolis 153 contains six names of the dramatis personae and

some forty lines of dialogue. Two other fragmentary papyri are printed in

the Loeb Menander, possibly belonging to the same comedy an containing

the beginnings and ends of another 36 resp. 16 verses. The name of the au-

thor and the title are nearly illegible, but have been interpreted as resp.

Menander and Apistos, ‘An Untruscworthy Person’. As Sandbach remarks

(Comm. 722) itis highly probable that a MS of the fourth century 8c con-

tains a Menandrean play, ‘and nothing speaks against his authorship’. In the

1 Cp the biblical use of to know’ sbout sexual intereoure.

12 Am. 2365-41 with new numbering co which I refer

15 Arm. 3505-27 under the tile Fabuda incerta 6.

(Cuassicn ET MEDIAEYALIA $3 - 2002

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK 18

first scene of the play 2 young man, who has been happily married for five

months, declares himself immensely unhappy. A servant shows him a box

containing objects that the man interpretates as recognition-tokens of a

child, kepe by the mother. His unhappiness may be due to his wife having

left him without an explanation, possibly because she has discovered that she

‘when she married was pregnanc after a rape, probably by the man she later

married, as in the Epitrepontes and in the Heeyra of Terence. The objects

found among her belongings in the search fora clue to her disappearence are

clearly old, e.g. a moth-eaten cloak and possibly a sword so rusty that it can-

not be drawn from its sheath," and so may have belonged to the young

wifes mother, providing another instance of rape in two generations.

PLAUTUS

Aulularia ‘The Pot of Gold’ usually is supposed to be modelled after a play

by Menander. Phaedra (or Phaedrium) is the daughter of Euclio. She has in

the night-time during the festival of Ceres been ravished by the drunken

Lyconides. He knew her and was in love with her, whereas she did not know

who he was. We are told so by the Lar familiar who delivers the prologue

(28-30, 36) and by Lyconides himself 10 Euclio (794-5). In a long and very

amusing scene between Euclio and Lyconides (731-807), Euclo talking of his

pot with gold which he believes Lyconides has stolen, the latter of his of-

fence to Phaedra who has just born his child (691), the culprit does not con-

ceal his guilt (but he does not repent):

Lyconides

Fateor peccaviseet me culpam commeritum sci;

id adeo te oratum advenio, ut animo aeguo ignascas mibi

Buclio

Cari ausu’ cere, ut id quod nom tuum eset rangers?

Lyconides

Quid vs fri? facurn est illu: feriinfecoum nom pores.

Deos credo voluise: nam ni vellent non fires, scio (738-42)

14 FeB.t, Arm. sats wx 20-4 w: comm, See also bid. p. 509, n. sand 6 with reference to

A Sceberg, Clasica & Mediacvlia 3 (1970) 2189.

182 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

Tyconides

[confess that I have sinned and committed an offence; 1 therefore come

to you to pray that you will resign and pardon me,

Buclio

How dared you go so far and touch what was not yours?

Lyconides

What shall | do? What is done cannot be undone. I believe it was the will

of the gods: for if they didnie want it done it wouldnit have happened, 1

know that

Buclio, when the truth eventually dawns upon him, reproaches him severely

(796 fF), (but not neaely so severely as when he thought that Lyconides was

talking about the gold, 745 ff). In the end the two lovers are united in be-

trothal, in accordance with the intensions and plans of the kind Lar.

intllaria “The Casker’. Adapted from Menander’s Syraristoua, The scene

isin Sikyon. Sclenium, a girl of seventeen, isa foundling, che issue ofa rape;

she has grown up in the houschold of Melaenis, a former courtesan, who is

now a procuress, bue not educated for her fostermother’s profession, because

she, out of some inborn high-class virtue, does not want ro be a meretrix.

She has been allowed to live together with one Alcesimarchus; they are head

over cas in Jove. But his father will force him into a marriage with a relative

and the gil is at her wits end, She consults Syra, a worldly-wise colleague of

het foster-mother, and Gymnasium, her daughter, to ask Gymnasium (olive

‘with her, for fear that Melaenis will force her to rerurn to her. Syra asks her

hhow Alcesimarchus made her acquaintance, which she tells them." There is

15 Syra

Opec,

(Quo is ome ininwavit pac we ad re?

Selenium

Per Diana

ater pomp me rectatum dst. Dum redeo domi,

ompcilacomecutue cancun me aque ad ores

inde in concise cm marr es mecon sd

blends, muneribus, deni, (88-92)

At ile oneepts irae verbs pad matrem meam

‘me uci ducturum exe. (89)

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK... 183

practically verbal correspondance between Menander and Plautus."® The

‘wo young people fell in love. Syra is righteously scandalized: in theie profes-

sion love is a vice, it is destructive to the trade. But everything ends a

should. Selenium is a legitimate Attic citizen, actually the daughter of

Demipho, the intended father-in-law of Alcesimarchus!

‘Apparently this is the romantic story of love at first sight. But alas! che

story is not as chaste as that. According to Hermogenes (see above) ‘to ap-

proach with compliments is a nicer way of expressing the fact chat she was

ravished. There is hardly any doubs that Hermogenes is right; wo details

which are common in such a situation are found here too. Firstly, in the pro-

logue (postponed) 156 fF. Auxilium, 2 godhead, relates how, seventeen years

ago, a youth, a Lemnian merchant came to Sikyon and during the proces-

sion vi, vinolentus, multa nocte, in via ’by force, being drunk, late at night,

in the street) raped a girl, to wit Selenium’s mother. Its likewise a recurring

feature that the enamoured culprit confesses to the gir!’ mother and prom-

ises to marry the girl.'7 As Cistellaria has many lacunae, and there are only a

handful of fragments of Synaristosa, we do not know how the pregnancy

developed, but itis highly probable that the expected birth takes place dur-

ing the play,

Epidicus® The original and its author are not known. This highly amus-

ing play shows a rape in che parents’ generation, Periphanes, the senex of the

‘comedy, 2 gentleman of high standing in Athens, in his youth paid a visit to

Epidauros where he ravished a giel called Philippa. During the play they

meet, Philippa having come to Athens in search of her daughter, who has

Syra

1 do want to know how this low wormed himself into your Favour?

Selenium

During the Dionysus festival my mother rook me co see the procesion. When we re

tured home he followed me dicretly and attentively tothe door: then he insinsated

himself into my mother’s and my friendship, with compliments, friendly turns, and pre-

Bar he vowed in solemn words in frome of my mocher, 0 take me for his wife

16 See above

17 Ex, Menander Samia 50-3: possibly Georgs-. Terence Adelphoi 470 fan exact parallel

1 Synarina.

18 Epidicus i the name ofthe lading character, slave,

184 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

been taken prisoner in the wat. They are uncertain whether they know one

another and have the following lines:

Periphanes

[Noscii ego hane; nam videor nescio ubi me vidise prius

Estme ea an non east quars animus retur meus?

Philippa

Di boni, vsitaui (...antidbac?

Periphanes

Corto east (...] quam in Epidauro

‘pauperculam memini conprimere (..-]

Philippa

Plane hicine st

qui mi in Epidauro virgin primus pudicitiam pepulit.

Periphanes

[se] quae meo compressu pepertfiliam, quam domi nunc habeo. (537-42)

Periphanes

T think I know her; for it scems to me that I have seen her. Is she, or ist

she the girl that I’m inclined to think?

Philippa

My gods, have I seen him before?

Periphanes

Surely itis she [...] whom I remember I went to bed with, that poor

litee gi

Philippa

Te she, and no mistake, who when I was chaste took my virtue away.

Periphanes

She who after my assault bore the giel chat I now have in my house.

(Che las relative clause is not true; that is what Epidicus has made him be-

lieve). They now do recognize one another. Periphanes has not forgotten his

illegitimate offipring abroad, and has some years later even sent her gifts by

Epidicus. But at the time of the comedy he is a widower with a son, Seratip-

pods, who has been ro the war, returning with a girl Telestis, whom he has

bought out af the boory, having fallen in love with her. Being moneyless, of

course, he borrowed the amount of forty minae from a moneylender, who

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK... 185

has followed him to Athens to have his due. Epidicus by a stratagem gets the

amount from Periphanes. As the mother and daughter meet they recognize

cach other, and Epidicus recognizes Telestis as the child he had brought the

gifts from her father. But so ic falls out that the lovers are brother and sister,

which is a chock to Stratippocles: perdidisti et reppersti me, soror ‘you have

found me and lst me, my sister!” (652). What Telests thinks or feels we do

not know. She disappears from the stage after I. 660, and is no more heard

of,

Their first meeting was not a rape, as we could have expected. On the

contrary. At his first entry Stratippocles tells his friend Chaeribulus of his

situation, his love and wane of money, and Chaeribulus asks:

Chaeribulus

] quis ert vitio qui id vortat ribi?

Stratippoctes

(Qui invident, omnis inimicos mibiilloc facto repperi:

«at pudicitiae eins numauuam mec vim nee vitium ateuli.

Chaeribulus

am isto probior es meo quidem anime, cum in amore temperes. (108-11)

Chacribulus

‘Who would blame you for that?

Seeatippocles

‘Those who envy me my happiness. I have found that everybody turned

my enemies because of that; but I have not assaulted her or fouled her vir

tue.

Chaeribulus

‘To my mind you are so much the more honourable, as you know how to

govern your passions.

The last three lines are missing in the oldest MS, the venerable Ambrosian

palimpsest, and have been condemned by some editors. In any case there

can hardly be any doubt why they are here, exactly because of the unhappy

ending. We expect a birth as we have seen it in the other instances of rape,

but in that case the child would be the offipring of an illicit, incestuous af-

fair and not a blessing to one and all, at any rate in Rome. In Athens the

connubial union of Stratippocles and Telestis would have been permitted by

186 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

law. !9 I think we need not hesitate to draw the conclusion that in the Greek

model 'Stratippocles' did rape “Telestis, and that chey like other pairs of lov-

crs married in the end. In Epidicus the real happy ending, which occupies

the lines 660-733, the end of the play, consists in the manumission of Epi-

dicus. Periphanes who had been tricked out of money by Epidicus now for-

gives him and rewards him generously when he underseands that he has

brought about the reappearance of his daughter. Epidicus even forces him to

ask permission co liberate him, the crowning triumph of the slave. 2°

Truculentus. Tide and. author of the original are unknown. In this in

many ways unique comedy* we have a sexual assault on a young girl. The

jeune premier, Diniarchus, an utterly good-for-nothing fellow, has at one

time been engaged to the daughter of one Calliles, but not because of any

kind of affection. During the engagement he has assaulted her in drunken-

ness and made her pregnant, without her discovering that the assaulter was

her fiancé. This circumstance makes ita rape, although of an extraordinary

kind, Afterwards he has broken the engagement in favour of Phronesium, a

ravenous meretrix, who has then cleaned him off. Shorely before the begin:

ning of the play the giel has been delivered of a boy. Callicles, however, dis-

covers the identity of the father and Diniazchus has to confess:

Diniarchus

Per tua obsecro

genua us tu istueinsipienter facturm sapienter fras,

‘ibique ignoscas quod animi inpos vini vito fecerim.

Callies

‘Non placer. In mutum culpam confers, qui non quit logui;

nam vinum si fabulari poset, se defenderc.

Non vinum viris moderari, sed viri vino solent,

(qui quidem probi sunt; verum qui improbus est si quasi bibit

sive adeo care temeto,tamen ab ingenio improbust. (826-33)

19 ARW. Harcson The Law of Athen (968) 23, with. ,

20 See Erich Sogal Roman Laughter. The Comedy of Plant (3968 and 1987) 109 f

21 The name, o nickname, ofa teslene slave

22 David Konstan in his Roman Comedy (1983) 142-64, the chapter “Trucuentun Satire

‘Comedy’ gives good account and interpretation of the play.

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK 187

Diniarchus

Verum te obscro ut rua gnatam des mibireorer, Callies.

Callicles

Eundem pol ve iudicasse quidem itam rem intellego;

nam hatid mans, dum ego darem illams: tute sumpsisi tb.

ume habeas ut nace’. Verum hoc te muleabo bolo:

ses talenta magna dots demam pro istainscisia

Diniarchus

Bene agis mecum. (841-6)

Diniarchus

I clasp your knees and pray that you will bear my unwise act as a wise

‘man, and forgive what I've done: wine made me loose my head.

Callicles

I dont like that! you put the blame on a mute that cant speak for itself,

for if wine could talk it would defend itself. Drink does not govern man,

it the man who governs his drinking, that is if he is righteous man. He

who is nor, whether he drinks or abstains from liquor, has an unrighteous

character.

Diniarchus

implore you Give me your daughter for a wife, Callicles,

Callcles

I see that youve passsed sentence upon yourself: you wouldnit wait for me

to leave her to you. Youve made your bed and you must lie on itt But this

is to be the penalty for your folly: I reduce the dowry by six talents.

Diniarchus

You are 100 good.

Whereupon Diniarchus at once streaks off co get to Phronesium again.

TERENTIUS.

“Andria “The Giel from Andeos.. After Menander. Pamphilus, son of Simo, in

the house of Chrysis, a meretrix, now deceased, has met her ‘sister, called

Glycerium, has fallen in love with her and made her pregnant. It is de-

188 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSPN

scribed as a rape, vitiat , the violates’ (arg. 2) and facere iniuriam , ‘to do

‘wrong’, a common word for ‘rape’ (488), equivalent with the Greek aicée,

‘met with above. Bur the love of the two young people is clearly reciprocal,

they have sworn to marry and live in eternal fidelity, and to let the boy (who

is bor in line 473 and is declared by the midwife ro be an ecastor situs puer

by Castor, a fine boy’, 486) live, They firmly believe thae Glycerium isa cvis

Attica, But unfortunately Simo and his friend Chremes have agreed that

Pamphilus should marry Cheemes' daughter. So: Chremes quite naturally

refuses to let his daughter marry him. After a good many complications the

knot is disentangled i 923 ff: Glycerium is proved to be Pasibula, a daughter

of Chremes, who many years ago was lost, taken by Phania, her undle, to

‘Andros under the threat of war. And all concerned afier all are satisfied and

happy.

Banuchus, After Menander. As always in Terence there are wo plots,

parallel and intertwined, Phaedria frequents Thais, a meretrix of noble

character. She has taken Pamphila, a gil of sixteen years (v. 526 f) into her

hhouse, whom she supposes to be the daughter of an Attic citizen. Phaedria

hhas promised her a eunuch to attend on the git. Chaerea, Phaedrias brother,

a forward young person - he to9 is, or is said to be, sixteen (v. 693) - happens

to see her in the street, exchanges clothes with the eunuch bought by his

brother (but without the latter's knowledge), gains access to Thais’ house

and rapes the gir, without loosing a minute. The endeavours of Thais bear

fruit, She has traced the brother of the gicl, Chremes, who can prove that

she is his sister and a legitimate daughter of a citizen. In her childhood she

was kidnapped by pirates, and later was captured by Thraso, a soldier who

also courts Thais and has presented the girl to her. And Pamphila and Chac-

rea can marry.

Hecyra ‘The Mother-in-Law’. After Apollodoros. The plot is similar to

Epitrepontes and the Papyrus Antinoopois, in that we here have a newly mar-

ried couple as the chief characters, Pamphilus and Philumena (who is not

cone of the dramatis personae). He has married her, not because he was in

love with her, being the lover of Bacchis, a meretrix, but because the fathers

desired it. Accordingly he has not consummated the marriage. But lice by

licde Pamphilus has become aware that she is a good and affectionate

woman, she has won his love, and he has dropped his connection with Bac-

chis, who very nobly has accepted the situation, And then he is sent by his

father on a business trip ~ a favourite way of creating complications — while

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK... 189)

the young bride has remained with her parents-in-law. But suddenly she

leaves their house and moves back to her own people without explanation.

‘Ac the same time as Pamphilus returns, looking forward to resume the mar-

ried life, she is delivered of a child. She has, as Myrehina, her mother, ells

Pamphilus, been the victim of a rape (v. 385: Nam vitium est oblatwm vingini

olim ab nescio quo improbo ‘for the maid was once deflowered by I don't

know which rascal’ as Pamphilus in a monologue retells what he has heard

from Bacchis). This causes great excitement, and Pamphilus does not want

to live with her under these ciecumstances, as the child must have been con-

ceived before marital relations were adopted. But then Myrthine happens to

sec her daughter's ring on Bacchis hand (the two families and the meretrix

being neighbours), and it is disclosed that Pamphilus was the culprit. He

had taken the ring from the girl, whom he did not recognize, and given it to

Bacchis! After the facts have been made clear the later in a long monologue

narrates how the facts were discovered: Homo fitetur vi in via nescio quam

compresise | dicingue see illi anulum, dium lucia, detnexsse le admits that

he has had intercourse in the street with I donit know whom, and says that

he had grasped her ring in the struggle’ (v. 828 f). It seems to be in very bad

taste for Pamphilus co have done so, bur it is necessary for the solution of

the knot. And everything ends happily.

‘Adelphoe “he Brothers. After Menander’s Adelphoi Il (one of two come-

dies of Menander with the same title) and Diphilos’ Synapoohneskontes

"Joined in Death’. There are two pairs of brothers, two old ones, Micio and

Demes, and two young men, Aeschinus and Cresipho, sons of Demea, who

has let his liberally minded bachelor brother adopt Aeschinus, while he him-

self has educated Cresipho after sterner principles. The two young men have

both of them fallen in love, Ctesipho with a meretrix, Aeschinus wich Pam-

phila, a young, impecunious girl. He has made her pregnant but promised

to marry her and sworn eternal fidelity. In a conversation between Sostrata

the gitl’s honest, but poos, mother and Canthara, her old nurse, the latter

introduces an unusual, but realistic view of the matter:

Canthara

E re nata melas fieri baud potuit quam fictumst, ent,

quando vitium oblatwmst, quad ad illum attinet potssinum,

talem, sali genere atque animo, natum ex tanta familia. (295-7)

CLASSICA eT MADIABYALIA $3 - 2002

190 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

Canthara

Ie could not have turned out better than it has, Mistress, that seeing she

has been seduced it involves such a fine young gentleman, of such a char-

acter and disposition, of such an important family.**

In other words: this is a blessing in disguise. At this moment Geta, Sostratas

slave, comes rushing with the hozrible news that he has seen Aeschinus with

another woman, whom he has abducted from a pimp (but she is in fact Cre-

sipho’ gi-friend, the meretrix, Aeschinus being involved in an intrigue to

help his brother in his love-affair). He must have deserted Pamphila. The

to women are shocked and Sostraa exclaims in her despair:

Sostrata

‘me miseram! quid oredas iam aut quoi credas? nosrumne Aeschinwn,

nostram vitam onium, in guo nostra spes opesque omnes stae

cenant? qui sine hac iurabas se unum numguam vieturum diem?

(qui sein sui gremio positurum puerum dicebatpasris,

ita obrecrasurum ut liceret hanc sbi uxorem ducere? (530-4)

Sostrata

(Oh no, no, What can one believe? Who can be trusted? Our Aeschinus,

the life of us all, in whom we put all our hopes and everything, who

swore he could not live a day without her! And he promised he would

pput the baby in its grandfather’ arms and beg the old man’s leave to

marry her!™*

“To her too, the rape should have been the door tothe happiness of her child.

‘Thanks to the endeavours of the other characters Ctesipho is made able to

purchase the freedom of his meretrix from her leno, and Aeschinus is mar-

ried to his Pamphila. The birth takes place in we. 486-7 when Pamphila is

heard to be in labour, imploring the assistance of Iuno Lucina.

25 Cp. Terence Adelphi, ed, RH, Matin (Cambridge 1976) 1.

tu Te Betty Radice, Terence. The Comedies Penguin (0965 and lace 354.

peep cages) Sus aee eg eee gee edie cease eas cesais ce sais cea mais cieamcimamiinameeas:

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK 19

In nine Menandrean comedies we find a consummated rape as part of the

plot, in four of them it looks as iF both the young giel and her mother owe

their existence to a sexual offence. To these we can add the fabulae palliatae

which were modelled on other comedies by Menander, Plautus’ Aulularia

and Cistellaria, and Andria; Eunuchus and Adelphoi of Terence, another five,

Jn Plautus we have rapes in four plays, in one of them in two generations.

In four of the six comedies of Terence we find the, one is tempted to say,

obligatory rap.

In about forty-five Greck and Roman new comedies we see that in seven-

teen, nearly wo fiths, a consummated rape is an essential element of the

plot. In a handful of them there are two rapes; both the young girl and her

mother owe their existence to a sexual offence.

In all of these che consequence of the rape is love and a happy ending,

‘excepting apparently Truculentus. And to the list of Attic playwrights we can

now add the unknown authors of Epidicus and Truculentus

Already in Hellenistic times the rape was acknowledged as one of several

characteristics of New Comedy. Satyros, the peripatetic grammarian (proba-

bly ard century nc), in his Life of Euripides which has been preserved frag-

mentically on a papyeus,%* has the following defective, but informative pas-

sage:

au] neds ywaika wai naxpl neds vlév wai Bepdnore mois Beonbrmy, Hv

ard tis nepimevetas, Bramunis napbbvuv, troBohds nadia, avarrrercte~

mods 21d re daxrudioy Kai dui Beonion, radra yéo dort Dimou ca

ouskxorra viv veurrépay wauodiay, ds nods lxcon yanen Ebpunins [

.-] towards his wife, che father’s towards his son and the slave’ towards

his master, or what has to do with the peripery: virgins raped, change-

lings, recognition by means of rings and necklaces; all this then, which

25 Pap. Oxy 1X 125; Grasano Anighet Stir, Vite di aripide, Pisa (1969) Pe 39 VU, p59.

192 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

hhad been developed to perfection by Euripides, constitutes the New

Comedy [...°6

“To Saryros che deflowered maid is a principal characteristic of the New

Comedy, like the conventional bad relations between man and wife, father

and son, master and slave; and like foundlings and anagnorismos as means

«o lead 0 the peripery and dénouement, all of which go to make a proper

comedy:

The world of comedy disposes of a range of recurring motives, used again

and again, explainable only by reference to the stage itself. (Incidentally, the

plots with che young couple, whose love is impeded by their elders, but

brought about, victoriously, by their servants, is one of the most common

and maybe the most improbable of the dramatical conventions. When was

there a society which permitted or enabled slaves and valets and soubrettes

to perform those admirable feats of cunning and cheating?)

In his excellent book The New Comedy of Greece & Rome (Cambridge

1985), RLL. Hunter has a chapter on ‘Plots and motifs: the stereotyping of

comedy’ (pp. 59-82). He examines a number of the stereotyped elements in

comedies, but does not mention rapes, which are treated in the following

section, ‘Men and women’ (pp. 85-95) in the chapter on “Themes and con=

flicts. In disposing like this Hunter has apparently taken the position that

this special element mierors actual social and sexual conditions in Athens. In

a note27 he refers to FH. Sandbach, saying that the latter ‘has a clear ac-

count of the legal position of both partes afer a rape’.*® Sandbach’s exposi-

tion is very good and clear. He says among other things:

‘Athenian law exposed to a civil suit or a criminal prosecution the perpe-

trator of a rape on a citizen girl? Rape, not seduction [sc. of a married

26 The translation is given with some reservation on account ofthe preservation ofthe tex

See alo Arrighesis translation, oc 87

27 B67, n.23 10.95

28 Sandbach Comm. 524

29 ARLW. Harrison, 0. (above, a. 19) 19 discusses the legal postion of rape. He noces that

‘the evidence, however, is almor entirely from Roman comedy and weters on thetric of

the Roman petiod In his footnote» he adds, ‘it ie difficult disentangle fourth-cencury

Athenian law out of this evidence. And S.C. Todd The Shape of Athenian Law (Oxford

1993) 276-7 says "We know next to nothing about the way in which rape at Athens was

legally regulated’

See

Y

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK 193

woman}, is sometimes explicitly said to be the beginning of the story and

must be supposed in other cases. Ifthe giel had been a consenting partner,

that would have have lowered her in the eyes ofthe fourth-cencury Athe~

nian, On the other hand, although rape was regarded as a disgraceful act,

it was by no means an unpardonable or unthinkable one. (P. 33)

What we have seen above bears out what Sandbach here says. But is the last

sentence, and the consequences drawn, completely crue? A rape was of

course always outrageous and certainly not unthinkable, and could pre-

sumably in some cases be forgiven by the victim and her people, which is at

any rate true in comedy, but Sandbach’s expression is nor far from suggesting,

thar rape was a next to everyday occurrence in better circles in fourth-

century Athens. This too seems to be true in the theatrical sphere. But T

should like to mention another phenomenon which is closely connected

with the rape, the exposure of new-born babes, which quite naturally, so to

say, is represented in some of the comedies mentioned above. It is known

that exposure was used as a somewhat harsh way of birth-control. But itis

subject to doubt whether it was as usual in Hellas as one could believe from

the plays. Sandbach himself writes:

Whether such exposure of children was practised in Athens of Menander’s

times has been much discussed. The evidence for it comes mainly from

the plays, which may be chought merely to use a traditional motive, not

to give a picture of current life. Certainly the happy ending, by which the

child is restored to its true parents, must have been an almost unknown

‘occurrence. Why then suppose that the rest of the story is any more true

to life? (Comm. 34)

‘Why, indeed? I do not see how exposure of children differs from rape in this

respect. We have, I believe, no reason to think that rape was “a picture of

ccrtent life, not'a traditional motive’, nor ‘that the rest of the story is any

more true to lif.

194 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

‘To resume: the cases of rape in comedies are numerous, and they have much

in common. In many cases they happen during a sacral festival in the ni

time, under the influence of wine; or the rape is 2 spontaneous act in the

street, in via. The rape is an offence against the young woman, the culprit

repents, and is rebuked by the girls father. In three cases the rape scems to

be quite unnecessary, in Cistellaria (Menander/Plautus) and the original of

Fpidicus and in Andria.

There are, as it has been seen, variations in the treatment of this proce-

dure, and none of the items of the list is absolutely impossible, but some are

undeniably very improbable, for instance in those comedies where the raper

and the raped gitl shorty afterwards meet fll in love, and marry happily

without recognizing each other; see e.g. the lines in Heros quoted above,

That the interval between the rape and the marriage is very short is seen

from the fact that the illicit fruit of the rape in some plays is born some

months after the marriage. This is the case in Menander’ Epitrepontes, che

Papyrus Antinoopolis, Terence Hecyra. In short: What is striking and impor-

tant for the question we began by posing is the frequency and the uniform-

ity of the plots with a rape asthe starting poine.

1 refer again to Satyros and his enumeration of the characteristics of com-

‘dy. He mentions the virgins raped, together with the well-known bad rela-

tions of husband and wife. When reading the comedies one very soon real-

izes the curious fact that whereas matrimony is the object of the desires of|

the young, wife and husband in the parental generation as often as not lead

a cat-and-dog life. Harsh jokes about domestic tyrants and viragos abound

(especially the second variety), though kind and reasonable parents, para-

doxically especially mothers, are seen. Similarly, as Satyros says, fathers and

sons are opposed: the old man does his bese to thwart the desires of his son

and prevent his love, and the son desires nothing more than duping his fa-

ther and cheating him, or his mother for thac matter, of the necessary money

to realize his fondest dreams. A remarkable exception are Demeas and Mo-

schion, his adopted son, in Samia, And further: the devored slave is never

compliant to the master of the house but risks his life, or a leas his back, to

assist his young master. (The ‘good’, ie. obedient, slave is ridiculous and

heaped with scorn). Ic is difficul to believe that this isa general realistic pic-

ture of life in Athens, that conditions have not been considerably more var-

VIS COMICA: CONSUMMATED RAPE IN GREEK 195

ied from house to house. If Satyros had thought that rape, as described in

the comedies, was a normal phenomenon, he presumably would not have

had it on his lise of typical conventions.

Sccondly I again stress the frequency of rapes in comedies. If Hunter and

Sandbach are right in thinking that rapes were looked upon with greater

equanimity than we do now, not least by the comic poets, still 1 can hardly

believe that a corresponding proportion of marriages in Athens should have

been based on a consummated rape.

‘Third and last: Dare we take the playwrights at their word when they pos-

tulate that these connections are not only the start of a married life, but also,

with the exception of Truculentus, as the beginning of a happy life for the

young till death do them part?

The conventional ingredients occurring in the rape-stories down to details,

all of chem undoubtedly based on reality, make it unlikely chat this isa fre-

quent or commonplace feature fetched from everyday life in Athens. The

universe of comedy is conventional as that of all other literary genres. As

Hunter rightly stresses: ‘we are moving in the self-referential world of the

theatre and the conventions are *...more important than the attempe t©

reproduce faithfully the pattern of life outside the theatre’.!° This is ac-

cepted by us, the public in che theatron. A few examples: Pyrgopolinices,

Plautus’ Mies glorioss, curiously does not know that his neighous, Periplec-

comenus, is a confirmed elderly bachelor. He unhesitatingly believes it when

he is told by his slave that Periplectomenus is married to a young wife, who

is desperately in love with the braggare warrior. None of them is said ¢o be a

new inhabicant in the street. A character so frequently presented as the para~

site is, as far as I know, practically unknown outside the world of the theatre,

from Epicharmos to Terence. All of these conventions of course had theit

counterparts in the Athenian world, buc their frequent appearances and their

constant acting with and against one another (reminding of the stock of

roles in the Italian commedia dell arte) belong to the stage.

The rapes and their consequences so often met with in the new comedies

‘of Greece and Rome cannot be explained and understood by reference to

30.0. 74 and 8

196 MOGENS LEISNER-JENSEN

actual social and legal conditions in fourteenth-century Athens and Hella,

‘They must be understood as a, to the poet, handy and immediately intelli

gible way of connecting two young people. Neither society nor Menander

and his colleagues can be accused of having had a cynical view of the suffer

ings of the young girls. Realism and probability, o improbabilicy, are largely

intelevane on the stage, of, rather, the stage has its own realism and probality

‘or improbality.

NOTES ON MENANDRI SENTENTIAE

by Vayos J. Liapis

Summary: The following critical notes ae complementary to my Modern Greek commen

tary on Mevisdeas riya parrot, which is soon to appeat The txt is reproduced from,

and the apparatus criccus is based on, S Jackel.) Teubner edition."

MON. 8 J.

“Amay 1 xépias tiBixoy depen BRABmy

‘sb coiag 18% wiplos © ven x8 dncov POny ai 3006, i 3B add, Meineke

(béoe x, etiam Charetis ft 126 J.] wires Fer BOvy. li 3006, 3 (wer)

‘As RJ. Parsons has indicated (in P. Oxy. ali 1974] p. 27), the papyrus’ read-

ing +8 duxoy has offered a new solution to an old problem. Nonetheless, one

‘may feel that Meinekes (@y), pointing as it isco a textbook case of haplog-

raphy, is too neat to be dispensed with; what is more, é appositely brings

cout the conditional sense of &3ixor.

[As regards che nariae lectiones béger and sire, Jackel has plumped for the

former, evidently on the parallel of mon. 119 (BA Bae déset oot xéoBos @Bixoy

«By 77 Marcovich dina») and mon. 422 (Kéobos normpéy Guia dei dpe!)

However, [should venture to put forth a defensio of rter (which can now

be dated as early as ap 3rd cent.) on grounds of style.* No one has noticed,

~ Thanks ate deco the many scholars who have been kind enough to read and comment

con this paper, thereby saving me from errors to0 numerous to mention: G.A. Christodow

Jou (Adhens), Ferando Garcia Romero (Madrid), A.E. Garvie (Glasgow), DIM. Mac-

Dowell (Glasgow), S. Mathaios (Nicosia), J-ThA. Papademettion (Athens), Th.

Stephanopoulos (Patras), A. Tkimaks (Nicosia), and S.Titsirdis Para) ll remaining

shortcomings are, of couse, my responsibly,

1S, Jacke, MenondriSonteniae. Comparatio Menandri et Philsions Leiptig 1964

2R Fuhrer Zar savichon Uheecung der Menanderentenzon Beiesge zur Klassischen

Philologie 145 (Konigstein/ Ts. 1982) 64. n. 395 also remasks that viet i in 20 der

buanalser

J Li Novo Manan Semen’ CEA (058) 9734

py nemepe wan ida

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Pavis (1989) Problems of Translation For The Stage. Interculturalism and Post-Modern TheatreDocument20 pagesPavis (1989) Problems of Translation For The Stage. Interculturalism and Post-Modern TheatreEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Dixon - Reading Roman WomenDocument132 pagesDixon - Reading Roman WomenEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ducos, M. (1990) La Condition Des Acteurs À Rome. Données Juridiques Et SocialesDocument9 pagesDucos, M. (1990) La Condition Des Acteurs À Rome. Données Juridiques Et SocialesEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Dunbabin - Theater and Spectacle in The Art of The Roman EmpireDocument172 pagesDunbabin - Theater and Spectacle in The Art of The Roman EmpireEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Moussy (2001) Esquisse de L Histoire Du Substantif PersonaDocument5 pagesMoussy (2001) Esquisse de L Histoire Du Substantif PersonaEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Arcellaschi (1990) Médéé Dans Le Théâtre Latin D'ennius À SénèqueDocument469 pagesArcellaschi (1990) Médéé Dans Le Théâtre Latin D'ennius À SénèqueEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Beacham, Richard - The Roman Theatre and Its AudienceDocument280 pagesBeacham, Richard - The Roman Theatre and Its AudienceEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Hunter (2002) Acting Down. The Ideology of Hellenistic PerformanceDocument18 pagesHunter (2002) Acting Down. The Ideology of Hellenistic PerformanceEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Bablitz (2007) Actors and Audience in The Roman CourtroomDocument301 pagesBablitz (2007) Actors and Audience in The Roman CourtroomEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Henry (1915) The Characters of Terence - Studies in Philology 12, 2, Pp. 55-98Document44 pagesHenry (1915) The Characters of Terence - Studies in Philology 12, 2, Pp. 55-98Enzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Tradición Manuscrita de TerencioDocument12 pagesTradición Manuscrita de TerencioEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Traill, A. (2001) Menander's Thais and The Roman Poets - Phoenix 55.3-4, PP, 284-303Document21 pagesTraill, A. (2001) Menander's Thais and The Roman Poets - Phoenix 55.3-4, PP, 284-303Enzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Dumont (1990) L Imperium Du Paterfamilias en Parenté Et Stratégies Familiares Dans L Antiquité RomaineDocument12 pagesDumont (1990) L Imperium Du Paterfamilias en Parenté Et Stratégies Familiares Dans L Antiquité RomaineEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- (Synthese Language Library 25) Gregory T. Stump (Auth.) - The Semantic Variability of Absolute Constructions-Springer Netherlands (1985)Document419 pages(Synthese Language Library 25) Gregory T. Stump (Auth.) - The Semantic Variability of Absolute Constructions-Springer Netherlands (1985)Enzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Gowers (2004) The Plot Thckens. Hidden Outlines in Terences ProloguesDocument17 pagesGowers (2004) The Plot Thckens. Hidden Outlines in Terences ProloguesEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Dubourdieu (1989) Les Origines Et Le Développement Du Culte Des Pénates À RomeDocument577 pagesDubourdieu (1989) Les Origines Et Le Développement Du Culte Des Pénates À RomeEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Alexandre-Guérin-Jacotot (Edd) (2012) - Rubor Et PudorDocument74 pagesAlexandre-Guérin-Jacotot (Edd) (2012) - Rubor Et PudorEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Le Guen-Milanezi (Ed) L'appareil Scenique Dans Les Spectacles de L'antiquiteDocument124 pagesLe Guen-Milanezi (Ed) L'appareil Scenique Dans Les Spectacles de L'antiquiteEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- KOVACCI - La Oración en Español y La Definición de Sujeto y PredicadoDocument8 pagesKOVACCI - La Oración en Español y La Definición de Sujeto y PredicadoEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Moussy - La Polysemie en LatinDocument159 pagesMoussy - La Polysemie en LatinEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- (Midway Reprints) Carl Darling Buck - The Greek Dialects - Grammar, Selected Inscriptions, Glossary-University of Chicago Press (1928)Document199 pages(Midway Reprints) Carl Darling Buck - The Greek Dialects - Grammar, Selected Inscriptions, Glossary-University of Chicago Press (1928)Enzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Gilula (1989) Greek Drama in Rome. Some Aspects of Cultural TranspositionDocument11 pagesGilula (1989) Greek Drama in Rome. Some Aspects of Cultural TranspositionEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Boyle (2004) Introduction - Terences Mirror StageDocument9 pagesBoyle (2004) Introduction - Terences Mirror StageEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Karakasis (2005) Terence and The Language of Roman ComedyDocument325 pagesKarakasis (2005) Terence and The Language of Roman ComedyEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Anna a. Novokhatko - The Invectives of Sallust and Cicero_ Critical Edition With Introduction, Translation, And Commentary (Sozomena Studies in the Recovery of Ancient Texts)-Walter de Gruyter (2009)Document235 pagesAnna a. Novokhatko - The Invectives of Sallust and Cicero_ Critical Edition With Introduction, Translation, And Commentary (Sozomena Studies in the Recovery of Ancient Texts)-Walter de Gruyter (2009)Enzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet

- Ocampo, S. - Epitafio - RomanoDocument6 pagesOcampo, S. - Epitafio - RomanoEnzo DiolaitiNo ratings yet