Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Michael Kennedy - From Casti To Capriccio Strauss (Missing 185)

Uploaded by

Gata Meera0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views20 pagesMichael Kennedy - From Casti to Capriccio Strauss (missing 185)

Original Title

Michael Kennedy - From Casti to Capriccio Strauss (missing 185)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMichael Kennedy - From Casti to Capriccio Strauss (missing 185)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views20 pagesMichael Kennedy - From Casti To Capriccio Strauss (Missing 185)

Uploaded by

Gata MeeraMichael Kennedy - From Casti to Capriccio Strauss (missing 185)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 20

Michael Kennedy

From Casti to Capriccio:

Strauss’s Theatrical Fugue’

It began under the shadow of Nazism. Since October 1932 Richard

Strauss had been working on his comic opera Die schweigsame Frau to

a libretto based on Ben Jonson by the Austrian Jewish novelist and biog-

rapher Stefan Zweig. After Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s death in 1929,

before a note of Arabella was composed, Strauss had despaired of find-

ing a librettist with whom he could work amicably. In Zweig, to his

relief and astonishment, he found one. Moreover, he found one who

deferred to him and, while ready to argue points, was far less touchy and

prickly than Hofmannsthal. He wrote to Zweig from Garmisch on 21

January 1934:

The score of the first act is completed. This news I can give you

today. I got 140 pages of the score done in 2 1/2 months, although

my appointment as Reich Music Chamber President [in November

1933] produces a lot of extra work. I believe I should not refuse

this task because the goodwill of the new German Government in.

' This essay draws primarily on the following sources: (1) A Confidential Matter: The

Lenters of Richard Strauss and Stefan Zweig, 1931-1935 (tans. Max Knight, from

Richard Strauss Stefan Zweig Briefwechsel, ed, Willi Schuh, Frankfurt, 1957), Berke-

ley and Los Angeles, 1977; (2) Richard Sirauss und Joseph Gregor Briefwechset

1934-1949: im Auftrag der Wiener Phitharmaniker; ed. Roland Tenschert (Salzburg,

1955; English translation of extracts in “Selections from the Strauss-Gregor Corre-

spondence: The Genesis of Daphne,” trans. Susan Gillespie, in Richard Strauss and

his World, ed. Bryan Gilliam, Princeton, 1992); (3) Richard Strauss - Clemens

Krauss: Briefwechsel, Gesamtausgabe, ed. Giinther Brosche (Tutzing, 1997); (4)

Rudolf Hartmann, Richard Strauss: die Buhnenwerke von der Urauffuhrung bis heute

(Fribourg, 1980); in Eng. translation by Graham Davies as Richard Strauss: The

Staging of his Operas and Ballets (Oxford, 1982), (5) Kurt Wilhelm, Fars Wort

brauche ich Hilfe: Die Geburt der Oper Capriccio von Richard Strauss und Clemens

Krauss (Nymphenburger, 1988); (6) Norman Del Mar, Richard Strauss, a Critical

Commentary on his Life and Works (London, 1972). 3 vols., vol. 3

17

172 MICHAEL KENNEDY

promoting music and theatre can really produce a lot of good; and

Thave, in fact, been able to accomplish some fruitful things and

prevent some misfortune... Now what? What suits me best are South

German bourgeois sentimental jobs; but such bull's eyes as the

Arabella duet and the Rosenkavalier trio don’t happen every day.

Must one become seventy years old to recognise that one’s greatest

strength lies in creating kitsch? But, seriously, don’t you have some

new, warm-hearted little theme for me?...

Three days later Strauss suggested “a nice one-act” piece from

Calandria by Bernado Dovici da Bibiena (1470-1520) as a complement

tohis second opera Feuersnot (1900-01). Zweig vetoed it and suggested

Kicist’s Amphitryon. “I supposc you arc right about Calandria,” Strauss

replied, while scotching the Kleist (“not my line at all”). But the post-

script to Strauss’s letter betrayed a glint in his eye: “I am waiting with

intense interest for your Abbate Casti.” Zweig had told him that on a

forthcoming visit to London he planned “to read through all the libretti

Abbate Casti wrote for Pergolese [sic] who, second-class musician that

he was, could not do justice to the great charm and the perfect comedy

style of these texts.” [Zweig must have meant Paisicllo. Casti was only

11 when Pergolesi died.] The Abbé Giovanni Battista Casti (1724-1803)

is not mentioned again in their letters until after they had met in Salzburg

in August 1934 when Strauss wrote on the 20": “I am now impatiently

waiting for further news from you, first the translations of the three Casti

operas, then your drafts for them...”

The further news he received from Zweig, in a letter written on 21

August, was an outline of a one-act festival play they had discussed

earlier, Strauss had suggested something “ending up with the Peace of

Constance, 1043, of the Saxon emperor Henry III.” Zweig countered

with a piece set in the last year (1648) of the Thirty Years’ War. His

synopsis was eventually to become Friedenstag. But two days later he

sent a postcard from Vienna:

Lam just studying Abbate Casti.. The small piece by itself is not

usable, but could easily be adapted. Delightful is the title, Prima la

‘musica, poi le parole (‘First the music, then the words') which, in

any case, ought to be retained for this light comedy...

Casti’s divertimento teatrale was written to be performed in Feb-

ruary 1786 in the imperial gardens of the Schéabrunn Palace in Vienna

and was set to music by Salieri (1740-1825). It formed a double-bill

with Mozart's Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario). Casti’s plot is

about a maestro di cappella (music director) and a poet who are re-

quired by their aristocratic patron to produce a scena for two singers,

FROM CASTI TO CAPRICCIO 173

one of whom is the patron’s mistress. The music director and poet argue

about preparations for the opera. The former says it must be ready in

four days, the latter wants longer. The music is already written, says the

maestro, the poet need only write verses to fit the notes — it is of litle

importance that the music should express the meaning of the text.

Eleonora, one of the sopranos, shows off her ability by singing extracts

from Sarti's opera seria Giulio Sabino (1781) and the maestro and poet

stage a scene from the opera (the score quotes Sarti direct). This is

interrupted by Tonina, a comic-opera soprano, and a comic aria is com-

posed for her. The women quarrel over who is to sing first and end by

singing together, one seriously, the other comically. The two harmonise

perfectly and the poet and maestro join in the final ensemble.

“Prima la musica, poi le parole is excellent,” Strauss wrote to Zweig

on 24 August 1934. Then “How about Casti?” on 10 October, after

blowing hot and cold about the Thirty Years’ War opera. A fortnight

later Zweig wrote from London to say that “the scenario for the little

one-act comedy is finished. I shall send it to you before I formulate the

final version”. But that final version was not delivered. Towards the

end of 1934, both Strauss and Zweig began to experience the difficulties

caused by Germany's leading composer collaborating with a Jewish li-

brettist once the Nazi régime had begun to promulgate anti-Jewish laws

and to persecute Jews. The matter was further complicated in Strauss’s

case. He held an official position, and he had a part-Jewish daughter-in-

law, two grandchildren who were Jewish because of their mother, a Jew-

ish publisher and a Jewish copyist. The Nazis too had a dilemma. If

they banned a new opera by their leading composer, the damage to the

new régime in international eyes would be great. Yet Die schweigsame

Frau broke all their laws. The libretto was submitted by Goebbels to

Hitler, who approved performances of the opera as a special exception.

In December 1934 Goebbels, in a speech in Berlin, rejected the conduc-

tor Wilhelm Furtwangler’s published defense of the composer Paul

Hindemith, whose opera, Mathis der Maler, contained a scene attacking

the burning of books — something which had occurred under the Nazis

‘on 10 May 1933 to books “unacceptable to the régime” — and had been

banned from performance in Germany. On 18 February 1935, Zweig

asked Strauss to delay performances of Die schweigsame Frau “in

order to avoid any connection with the events in the musical world

(Furtwiingler, and so on).” Strauss said there was no need to worry

about anything now that Hitler and Goebbels had approved. “Dresden

also has made its announcements for June-July, so fate must take its

course.” He then made an extraordinary suggestion:

m4 MICHAEL KENNEDY

But for the future: should I have the good fortune to receive one or

several libretti from you, let us agree that nobody will ever know

about it or about my setting them to music. Once the score is fin-

ished, it will go into a safe that will be opened only when we both

consider the time propitious.

Zweig must have been flabbergasted. He candidly reminded Strauss

that it was inappropriate, in view of the historical greatness of his posi-

tion, that “something in your life, in your art, should be done in se-

crecy,” In any case, he said, the secret would be bound to leak out. He

‘was aware that for him, Zweig, to write a new libretto would be “a provo-

cation,” but he would be happy “to assist with advice anyone who might

work for you...without credit or reward.” Strauss was adamant.

I will not give up on you just because we happen to have an anti-

Semitic government now. I am confident the government would

place no obstacles in the way of a second Zweig opera and would

not feel challenged by it if I were to talk about it with Dr Goebbels,

who is very cordial with me. But why now raise unnecessary ques-

tions that will have taken care of themselves in two or three years?

This is clear evidence that Strauss over-estimated his influence with

the new régime and that (like many others in Germany) he lived in a

cloud-cuckoo-land of belief that the Nazis would not be in power for

long. Zweig then seemed to relent. He had been accepted as a member

of the Association of German Playwrights and he suggested an opera

based on the Spanish play Celestina (“a female Falstaff”). That was on

14 March. On 2 April Strauss told him that Goebbels had forbidden a

second Zweig opera. He had told Goebbels that he would continue to

compose Zweig texts in secret “for my desk drawer, for my pleasure. for

my estate... Please continue to think also about the Westphalian peace

and the Casti comedy.” Strauss continued to ply Zweig with ideas —

Celestina pethaps; Semiramis — and when Zweig had two plays by

Alexander Lernet-Holenia (a 38-year-old Austrian poet and novelist with

whom he had collaborated) sent to Strauss, the composer erupted with

indignation: “I frankly don’t know what to think of you. You cannot

seriously believe that a man capable of publishing such silly, tasteless

and witless stuff could write a libretto for me?

‘Two days later, 26 April 1935, Zweig put forward his intimate friend

Joseph Gregor as “your best collaborator, and you would know that I,

bound to him in friendship and to you in admiration, would participate

in his work with true devotion.” Gregor (1888-1960) was a Viennese art

historian, founder and director of the theatre collection in the Austrian

National Library in Vienna. Zweig set him to work on a Semiramis

FROM CASTITO CAPRICCIO 175

libretto for Strauss. When Strauss read it, he described it to Zweig as “a

fetus... Any critique is superfluous, A philologist's childish fairy-tal

Now what? Please don’t you forsake me.” But Zweig knew by now that

he had to forsake him, He wrote on 19 May:

The official measures, instead of getting milder or more concilia-

tory, have only grown harsher. Some of these measures cannot but

offend one’s sense of honour... You will discover yourself, I fear,

that the cultural development will more and more go to the side of,

the extremists... As an individual one cannot resist the will or in-

sanity of a whole world.

Strauss replied:

Neither of us can follow a path different from that prescribed by

‘our artistic conscience. Only one command exists for us: to be

creative for the good of mankind.

They met in Bregenz on 2 June. By 13 June Strauss had gone to

Dresden for rehearsals of Die schweigsame Frau. He railed against Zweig

for insisting on

saddling me with an erudite philologist [Gregor]. My librettist is

Zweig; he needs no collaborators... You write those two operas for

‘me, as you told them to me in Bregenz: 1684 (it was superb)! And

the comic opera Prima la musica (in Eichendorff’s style for all 1

care ) — that’s all I need.

He ended the letter:

Here the rumor is making the rounds that you have assigned your

royalties to the Jewish Emergency Fund. I have denied it.

Strauss was obviously still terrified that his opera would run into trouble.

The rumor was true and Zweig kept to his decision. He wrote to Strauss

very frankly on 15 June ina letter that has not survived. But from Strauss’s

reply we can safely deduce that Zweig had declared his solidarity with

Jews persecuted by the Nazis and pointed out that as librettist of Die

schweigsame Frau he could be viewed as a collaborator with a Third

Reich official. And he seems to have mentioned two events in 1933 for

which Strauss had been criticised: his substitution for Bruno Walter at a

Berlin concert and for Toscanini in Parsifal at Bayreuth. Strauss replied

from Dresden on 17 June. He was furious:

This Jewish obstinacy! Enough to make an anti-Semite of a man!

‘This pride of race, this solidarity!... I know only two types of people:

those with and those without talent... Who told you that I have ex-

posed myself politically? Because I have conducted a concert in

176 ‘MICUAEL KENNEDY

place of Bruno Walter? That I did for the orchestra's sake. Be-

cause I substituted for Toscanini? That I did for the sake of

Bayreuth... Because I ape the presidency of the Reich Music Cham-

ber? That Ido only for good purposes and to prevent greater disas-

ters! I would have accepted this troublesome honorary office un-

der any government... So be a good boy, forget Moses and the other

apostles for a few weeks and work on your two one-act plays... The

show here will be terrific. Everybody is wildly enthusiastic. And

with all this you ask me to forego you? Never ever!

Five days later a slightly mollified Strauss wrote again hoping Zweig

was “not too angry” about the previous letter.

Lam still so desperate about your obstinacy in wanting to foist on

me your own work under someone else’s name. If you could just

see and hear how good our work is, you would drop all race worries

and political misgivings with which you, incomprehensibly to me,

unnecessarily weigh down your artist's mind and you would write

as much as possible for me and not have anything written by others.

He was, as we would now say, “on a high” about the new opera. It was

to be taken to London for a guest performance.

Dr Goebbels, who will be here with his wife on Monday, will give

a government subsidy for this. As you see, the wicked Third Reich

has its good aspects, too.

Poor self-deceiving Strauss! In his single-minded egocentric ab-

session with his own work—and that was Strauss, you have to take him.

thus or leave him — he could not begin to fathom Zweig’s position.

Moreover, he did not know that his angry letter of 17 June had never

reached Zweig. It was removed from the hotel postbox by a member of

the Saxony Gestapo who sent it to the Governor of Saxony. Meanwhile

on 22 July, the day of the dress rehearsal, someone told Strauss that the

Dresden Intendant, Paul Adolph, had ordered the removal of Zweig’s

name from the printed program. Strauss, while playing his favorite card-

game Skat, suddenly demanded to see a proof. He wrote Zweig’s name

back in and threatened to leave if it was not reinstated by the printer. He

won his point, but Adolph was dismissed by the Nazis a few days later.

The world premiére on 24 June was a success, but neither Hitler nor

Goebbels attended, Strauss also attended the second performance on 26

June then returned to Garmisch the next day. The planned third perfor-

mance was cancelled because Maria Cebotari, who sang Aminta, was

ill. The performance on & July was broadcast. All subsequent perfor-

mances in Germany were banned: some time after 26 June, the Saxony

governor had sent Strauss’s letter directly to Hitler. On 6 July Strauss

FROM CASTITO CAPRICCIO 7

went to Berchtesgaden to meet Gregor the following day. There he was

met by a Nazi official sent by Goebbels to demand his resignation as

president of the Reich Music Chamber. Strauss suddenly realised that

“race worries and political misgivings” were not incomprehensible. With

fears for his family foremost in his mind, he wrote a terrified, grovelling

letter to Hitler trying to explain his “improvised remarks” to Zweig.

‘The Fuhrer ignored him.

After 29 June there is a gup of four months in the Zweig-Strauss

correspondence. Strauss had taken from Gregor at Berchtesgaden draft

librettos of Friedenstag and Daphne. He wrote to Zweig on 31 October

complaining about Gregor’s libretto for Friedenstag (“your version is

bettor fitted for the stago and more concise”). In Daphne he found

“schoolmarm banalities.” Then he returned to the fray:

‘Wouldn't you yourself work on something for me? Celestina and

Poi le parole, doppo la musica? {sic}... 1am mailing this letter

from Tyrol and am asking that you had also better not write to me

across the German border because all mail is being opened. Please

sign your name as Henry Mor; [Henry Morosus is the nephew in

Die schweigsame Frau) | will sign as Robert Storch (the name un-

der which he portrayed himself in his opera Intermezzo]. It would be

better if you were to send me mail by messenger or through Gregor.

Effectively that was the end of the Strauss-Zweig collaboration. I

have dwelt at length upon it because it is necessary to show how Joseph

Gregor came on the scene and how much importance Strauss attached to

the Casti one-act opera. Even though Strauss declared to Zweig that

“my life seems to have definitely come to a full close with Die

schweigsame Frau... Pity!” he could not live without work and he tack-

led Friedenstag, being exceedingly rude to Gregor in the process. In

fact, the libretto of Friedenstag is largely the work of Zweig, as was

acknowledged for the first time in the program for the revival of the

opera in Dresden in April 1995. It was the same with Daphne. This was

Gregor’s work, but Strauss criticised it mercilessly until he got it into

the shape he wanted. Gregor ended it with a choral apotheosis about

which Strauss was never happy. He talked over the problem with his

friend Clemens Krauss, who had conducted the first performance of

Arabella in 1933 in Dresden. Krauss suggested a wholly orchestral de-

piction of the metamorphosis of Daphne into a tree with just a few bars

‘of wordless melody from Daphne. This proposal was followed by Strauss.

‘What next? The idea of Celestina re-emerged. But the Swiss music

critic Willi Schuh sent Strauss a copy of a periodical, Corona, in which

‘was printed the draft of a scenario, Danae, oder die Vernunstheirat

178 MICHAEL KENNEDY

(Danae, or the Marriage of Convenience), which Hofmannsthal had writ-

ten for Strauss in 1920, For whatever reason, Strauss was not interested

at that time, put it in a drawer and forgot it until 1933 when he gave it to

the publisher of Hofmannsthal’s collected works, who printed it in Co-

rona. This, Strauss declared, was what he now wanted. Poor Gregor

‘was again subjected to a barrage of verbal abuse and again, when there

was a problem over how to end the opera, Krauss provided the solution.

By now, Gregor must have been heartily sick of the mention of Krauss's

name. The opera Die Liebe der Danae, was completed on 28 June 1940,

when Germany had conquered most of Western Europe in the Second

World War. Remembering that Die Frau ohne Schatten had suffered at

its premiére in 1919 because of immediate post-war conditions, Strauss

ordained that Danae should not be performed until at least two years

after the cessation of all hostilities. “That is to say,”, he told Gregor, “it

will take place after my death. So that’s how long you will have to

possess your soul in patience.”

Following his usual practice, Strauss had begun casting around for

his next subject before he completed the music for Danae. In March

1939 he surprised Gregor by returning to the subject of the Casti one-act

plece, envisaging it as a curtain-ratser to the double-bill of Friedenstag

and Daphne, or to one of them. Gregor was aware of the composer’s

interest in this subject because in June 1935 during a holiday in Zurich

he and Zweig had discussed the Casti scenario with a view to converting

it into a libretto for Strauss. According to Gregor

neither of us knew what to do with it... We became obsessed with

an idea: a group of comedians come upon a feudal German castle;

they fall headlong into a delicate situation; a poet and a musician

both sue for the hand of the lady of the castle; she herself does not

know which to choose...we were at once of the same mind that

such a band of players must have a magniloquent director, a blunt

caricature of that so much revered Max Reinhardt, full of his art,

full of the theatre.

This scenario was sent to Strauss, with a covering letter from Zweig

in which he bowed out of the venture. This annoyed Strauss so much

that he rejected the draft. Now, four years later, he had looked at it again

and within four days Gregor had revised it. “A disappointment” was the

not unexpected response from Garmisch:

Nothing like what I had in mind, ie. an ingenious paraphrase on

the subject of

First the words, then the music (Wagner)

FROM CASTITO CAPRICCIO 179

or First the music, then the words (Verdi)

‘or Only words, no music (Goethe)

or Only music, no words (Mozart) to jot down only a few

headings!

Inbetween there are naturally many half-tones and ways of playing

it! These all presented in various light-hearted characters who over-

lap and are projected into cheerful comedy figures — that's what I

have in mind!... In Italian opera the prima donna and tenor regard

the words as unnecessary as long as the cantilena is nicely executed

and the notes themselves bewitch the ear... In.an opera which even

half makes sense, if for whole stretches you don’t hear a word of

the singer’s part — this is also impossible. Three hours long only

notes — unendurable!.

‘The truth was that Strauss wasn’t completely sure what he had in

mind. As far back as July 1933 he had spoken to Krauss ahout his ob-

session with the relative importance of words and music in opera. In

September 1939 he wrote to him that he wanted to write “an opera about

opera, something wholly spirited and original. I really don’t want to

compose another opera; I'd like to make something really special out of

the de Casti, give it a dramaturgic treatment, a theatrical fugue (even

good old Verdi resorted to a fugue at the end of Falstaff) — think of

Beethoven's Quartet fugue — these are the sort of things old men amuse

themselves with! I can’t say yet whether old Gregor is capable of some-

thing like that... So far he has not understood what I really want: not

lyric poetry, not drunken emotions but intellectual theatre, food for

thought, dry wit...” Nothing that Gregor could produce matched these

vague ideas. Strauss showed each Gregor draft to Krauss who was sav-

agely critical, more critical than Strauss who, on 5 July 1939, had unexpect-

edly described Gregor's latest draft as

excellent...perhaps just what I had in mind: a pleasant comedy of

intrigue with a deeper underlying idea! Of course everything now

depends on the witty forming of the dialogue, which I imagine in

natural prose (apart from the actual ‘songs’) and which I intend to

compose as pure seco recitative (as in the prelude to Ariadne) just

with piano accompaniment.

On one day in Garmisch, Strauss and Kranss discussed the problem with

the producer Rudolf Hartmann (who worked with Krauss in Frankfurt

and Munich). Asa result, Strauss, Krauss and Gregor decided to submit

asketch of the dialogue for the opening scene to each other for “judgment.”

Strauss’s was adjudged the best, which enabled him to ask Gregor to cease

180 MICHAEL KENNEDY

“struggling with the ‘problem child’... I now intend to try my luck myself,”

reminding him that he had written his own libretto for Intermezzo (1924).

Strauss now decided on the date and place of the action: “a chateau

near Paris at the time (about 1775) when Gluck was beginning his work

on the reform of opera there.” Strauss thought the castle proposed by

Zweig and Gregor should be the home of a young Count and Countess,

perhaps twins. The Countess — who it was eventually decided should

be a widow — would be

not an insipid German girl but a 27-year-old French woman of the

world with a correspondingly liberal attitude in matters of love and

more serious aesthetic concepts than her brother, the philosophical

theatre-lover and dilettante.

He added:

‘The love issue concerning the Countess must run side by side with

the artistic question of Words and Tone, Word or Tone; that she

experiences the same sympathetic feelings for the poet as for the

musician, but in a different way...

He visualised a single act in four or five scenes and that the extra char-

acters and episodes would be the theatre director (to be modelled on

Max Reinhardt), two Italian singers, a string quartet, an actress (who

has a liaison with the Count) and a rehearsal of a play. Strauss’s long

outline of the plot can be summarized to show its salient points:

I. Poet and musician with Countess. String quartet in honour of

the Countess’s birthday. Corresponding sample of the poet's verses.

Duet from the Italian one-act opera which the Director is preparing

(here clearly in some sparkling dialogue the theatrical problem

[words v music] is partly broached, partly settled).

TL Countess, poet and m

bringing to life the poet’s verses...by improving their musical set-

ting,

Ill. The big ensemble in which all theoretical concerns as well as

those of the heart should be brought together culminating in the

decision that poet and musician collaborate on the complete opera, 10

be perfurimed un the birthday of the Count and Countess in six weeks’

time.

IV. The Countess alone with the song.

After this outline, Strauss suggested further scenic details. The

most significant were:

FROM CASTITO CAPRICCIO 181

‘The curtain rises after the quartet-introduction... The Countess is

listening dreamily; on her right are the composer, poet and director,

on the left the Count with the actress who is bored and they carry

on a flirtation... When the music ends...the butler gives a sign to

four young waiters to serve tea during which the five [finally eight]

servants overhear snatches of the theoretical discussion which fol-

lows. The Countess confesses she is stirred by music but perturbed

by emotions she does not understand, hence is not wholly satisfied

by absolute music. The Count...recites the poet’s verses... The

Countess very much likes the poem but, as with music alone, is not

wholly satisfied. Now the director contributes his view with the

trite outlook of the man of the stage as regards the subordinate role

of poet and musician alike when compared with the scenery, décor,

the exhibiting of pretty girls, costumes and nice voices... Here also

is laid the foundation stone for the later discussion of the five ser-

vants who should represent the broad public... The great Quarrel

Ensemble should begin with the introducing of the Italians’ duet,

criticism of which sets off the debates... This could lead to the

recitative scene between the Count and the actress so as to prove

that spoken drama actually makes quite a different spiritual im-

pression from the Italians’ sing-song with a wholly meaningless

stupid subject as pretext. Out of the gradually developing quarrel

comes the decision by poet and musician to write the real opera..

In the end, conciliatory resolutions: all three one-acters will be

played and the Countess will give the ultimate judgment! Whether

the scene of the servants, where they quarrel over which of the

principles (that they have overheard) they should follow in con-

cocting their satyr-play, comes next — that will emerge later. Each

of them could suggest something different! The whole perhaps a

whispered dialogue. When the Countess comes back they vanish!

The basics of Capriccio as we know them are there, but much was

yet to happen. Although Strauss’s decision to write the libretto himself

rid him of Gregor, he was still unsure.

I-can paint well-polished scores”, he wrote to Krauss, “but I need

help for words [firs Wort brauche ich Hilfe. This phrase was taken

by Kurt Wilhelm as the ttle of his indispensable book on the gen-

esis of Capriccio]. You must write it.

Krauss agreed to collaborate. One should in this respect be aware of

Strauss’s letter to his designated biographer Willi Schuh, written on 10

December 1942, six weeks after the premiére:

Krauss is so proud of his libretto that up until now Twas quite happy

to ascribe the authorship to him, or at least 1 said nothing if he

182 MICHAEL KENNEDY

claimed it all to be his. I shall continue to say nothing for the sake

of his other great efforts on my behalf and for my work. However,

in the biography a few discreet statements must be made, in par-

ticular that the main ideas came for the most part from me, the

very deft formulations in the text (some entire scenes) were mainly

by Krauss.

Krauss’s scenario was more complex than Strauss’s, but it contrib-

uted several important ideas. He did not want spoken dialogue. He

enlarged the quartet to a string quintet and he suggested that the Count

and Countess should be listening off-stage. He suggested that the poet

should arrange a meeting with the Countess on the following day at the

saune Lime as she fad agreed wy see the inusician and that the Countess,

elegantly dressed, should enter alone after the servants have left. After her

monologue, she leaves when the butler announces that supper is served.

It was time now to think of detail. First, there was the question of

the verse which the poet has written and which the musician sets to

music. Krauss had an assistant conductor, Hans Swarowsky, in Munich

to whom he gave the task of searching French literature of the period for

something appropriate. Swarowsky found nothing in the period in which

the opera was to be set, but found a sonnet by Pierre de Ronsard from

the 16" century: “Je ne scaurois aimer que vous". Strauss was de-

lighted and set it to music at once (on 1 December 1939). The final

version in the opera is slightly different. Next, they needed to find a text

for the Italian singers’ duet. Look in Metastasio, said Krauss, and in

January 1940 he found a simple song of a youth parting from his loved

‘Addio, mia vita, addio, / Non piangere il mio fato; / Misero non

son’io,” This is the duet between Emirena and Farnaspe concluding Act

1 of Adriano in Siria, a libretto set at least 65 times, by composers in-

cluding Pergolesi. 'This particular text is one of Meyerbeer's early 6

Canzonettes italiennes (1810). However, Strauss has switched the first

two stanzas of the tenor's text, e.g. in the Metastasio text the first stanza

begins Se non ti moro allato,

As the two men worked in the early part of 1940 in a flurry of

correspondence about new ideas and revisions, the characters acquired

names: the Countess, Madeleine; the musician and poet, Flamand and

Olivier; the director, La Roche; the actress, Clairon (she really existed,

Clairon Legris de Latude); the prompter, M. Taupe (mole). Only the

Count remains anonymous. Thanks to the existence of their letters, we

can trace almost day by day how the final libretto took shape. On 18

November 1939, the Italian Dancer was invented. Krauss researched

the popularity of Gluck’s operas in Paris and was thus enabled to pin-

FROM CASTITO CAPRICCIO 183

point the period of the action as the winter of 1776-7 (later they decided

on May 1777). He discussed the real Clairon on 22 November. The next

day he gave Strauss details of the programme La Roche devises for the

Countess’s birthday — the “Destruction of Carthage” was proposed by

Rudolf Hartmann as the genesis of the Quarrel Ensemble.

What was originally conceived as a 45-minute curtain-raiser to the

one-act operas Daphne and Friedenstag (an evening that would have

lasted at least 3 hours 45 minutes without intervals!) was growing to

larger proportions. Even so, Daphne was still being retained as the op-

era to be composed by Flamand and Olivier, to be presented to the Count-

ess and audience after the interval. (There are brief quotations from both

Daphne and Ariadne auf Naxos in the score of Capriccio — between

cue nos. 220 and 221 — which some conductors are barbarians enough

tocut!) Krauss was dubious. Such a double-harness could easily lead to

few performances. Strauss was eventually persuaded that the double-

bill would be impracticable, whereupon he had a marvellous idea: the

“opera-within-the-opera” in honour of the Countess’s birthday should

be about the events in which she and her guests were participating. He

thereby gave Capriccio its unique feature. It became a mirror-image of

itself, and the mirror became its symbol. It cannot be chance or coinci-

dence that the great melody which symbolises opera had been written

22 years earlier for the song-cycle Krdmerspiegel (Shopkeeper’s Mir-

ror, 1918). It is said that Strauss had forgotten this melody and that his

son Franz reminded him of it, saying that so beautiful a tune should not

be buried in a song-cycle which had (then) only been printed privately

because the 12 songs satirised the leading German publishers of the day

with whom Strauss had been in dispute over performing rights.

Itis difficult to believe that Strauss had forgotten the melody, since

his memory for music, whether his own or others’, was phenomenal. In

this case, too, the melody was singularly apt for its purpose. In Capric-

cio Strauss was intent on projecting, with the lightest of touch, a de-

tached view of opera as both sublime and ridiculous. The melody first

insinuates itself into the texture in the orchestra when the Countess, who

personifies opera, sings that

the theatre unveils for us the secrets of reality. In its magic mirror

(Zauberspiegel) we discover ourselves. The theatre moves us be-

cause itis the symbol of reality (scene 9, five bars after cue no. 137).

At the word “mirror,” the 1918 melody is first heard yet it does not

flower fully until a few pages later when the Count sings “An opera is an

absurd thing” and goes on to mock operatic conventions — “a murder

184 MICHAEL KENNEDY

plot is hatched in song...suicide takes place to music.” Strauss uses his

melody for the dual purpose of underlining opera’s magic power to dis-

close reality and its absurdity. This ambivalence was present, too, in

Kriimerspiegel, where the melody occurs twice. In the eighth song it

forms the long piano prelude and postlude to the words “Art is threat-

ened by businessmen, that’s the trouble. They bring death to music and

transfiguration to themselves.” Even more significantly, in the last song,

it is re-introduced at the word Fulenspiegel (‘Owl-mirror’) when the

singer asks who will stop these merchants’ evil ways and answers “One

man found a jester’s way to do it — Till Eulenspiegel.” The melody, we

discover, is a sublimated variant of Till’s principal motif. Nothing is

more typical of Strauss’s genius at its ripest than the combination of

Jesting and tenderness which makes ill Kulenspiege! the most endear-

ing of the tone-poems. Capriccio, too, is suffused with a comparable

blend of poetry and humour in perfect symphonic equipoise.

Although Strauss did not complete the full score of Act 3 of Die

Liebe der Danae until 28 August 1940, in the same month he began to

compose Capriccio — the introduction (now a sextet) and the opening

scene as far as the first words spoken by La Roche. He played the first

two scenes to Krauss on 4 September. Later that month he re-wrote the

Ronsard sonnet in F3, having decided that his original A major was too

high. Krauss delivered the end of the libretto on 18 January 1941 and on

24 February Strauss completed the short score. The full score was com-

pleted on 3 August 1941. I believe it to be the greatest, the nearest to

perfect, of Strauss’s operas, comparable with Verdi's Falstaff in its

summation of a long-lived composer's wisdom and mastery of form and

content. There is no doubt that Salome is his most advanced and revo-

lutionary opera score, uncuttable in its total cumulative impact, and that

Elektra runs it close in emotional power. Die Frau ohne Schatten is the

grandest of his scores, Ariadne auf Naxos the most original and elegant,

Der Rosenkavalier the most appealing to the wider public, Intermezzo a

very special case of melodic recitative transformed into unending melody,

But Capriccio represents all the best in Strauss purged of the excesses

which worry all but his most devoted admirers. It owes a lot to the

conversational style of both the Prologue to Ariadne auf Naxos and In-

termezzo, while the aura of gentle melancholy that suffuses the score

derives from Act 3 of Die Liebe der Danae. This was the starting-point

of what is known as his “Indian Summer” period when he regained all

the freshness of his early invention and combined it with an autumnal.

serenity and tenderness running through the whole of Capriccio, the

instrumental masterpieces which followed from 1942 to 1948 and the

final glorious effulgence of the Vier letzte Lieder.

186 MICHAEL KENNEDY

they have seen and heard during the afternoon; then the mysterious shad-

owy music as M. Taupe the prompter emerges after having fallen asleep

in the rehearsal-room. His subsequent dialogue with the major-domo is

both touching and, in some indefinable way, haunting. The mirror-im-

age of the work is retained to the very end, when Madeleine asks her

own image in the mirror to find an ending for the opera that is “not

trivial.” Her last gesture before going into supper is to glance in the

mirror. As she leaves, the major-domo, astonished by her behaviour,

looks back into the mirror as though he might find an answer there. The

conflict between words and music is, possibly, left unresolved, but we

can be in no doubt that Strauss wants us to believe that music has won.

During rehearsals when Krauss was stressing to the cast the importance

of clarity of diction, Strauss was heard to mutter: “Well, if a little of my

music is heard now and then, I shan't object.”

Next to the Countess, whose final aria is one of the high peaks in

all Strauss, the most engrossing role is that of La Roche, the theater

director. Like Clairon's, the name was borrowed by Gregor from real

life. Johann Laroche or La Roche (1745-1806), a Viennese actor from.

the Volkstheater, was the creator of the Wiener Kasperl, the Vienna clown

or Punch (as in Punch and Judy). In an article in the Journal of the Rich-

ard Strauss Gesellschaft (Vol.47, June 2002), Dagmar Saval-Wiinsche

observes the similarity between La Roche's aria and much that was said.

by Max Reinhardt to Arthur Kahane, his dramaturg at the Deutsches

Theater in Berlin from 1902. In his Das Tagesbuch eines Dramaturgen

(Diary of a Dramaturg, Berlin, 1926), Kahane quoted the transcript of a

conversation with Reinhardt at the Café Monopol in Berlin in 1902.

Reinhardt spoke of his vision of the theatre as a place that

gives pleasure to people, that leads them away from the grey mis-

ery of everyday life to the cheerful atmosphere of beauty.... lam not

afraid to experiment if I believe in its value, but will not experi-

ment for experiments sake... I believe in a theatre that belongs to

the actors.

These are not the actual words of La Roche in the opera, but they prob-

ably gave Gregor the idea for the character, But it was Krauss who

rounded him out more fully and, almost certainly, Strauss who injected

the real meat into the text of the aria. Krauss wrote to Strauss concern-

ing his own first draft of the text:

[La Roche] should justify himself as the specialist of the theater

whose duties even embrace light music, but only where it is on an

artistic level, Singspiel, or good comic opera and ballets... [he]

should nevertheless remain a sympathetic advocate for practical

thinking in the theater, which also supports great art out of its pro-

FROM CASTI TO CAPRICCIO 187

ceeds... His speech should finish comically and bombastically, per-

haps so that he blows his own trumpet and crowns himself with the

halo of the Art Patron... As a result he somehow remains a sympa-

thetic figure and never sinks to the level of a provincial hack.

Modeled on Reinhardt he may have been, but his words are often

the voice of Strauss himself, the practical man of the theatre, the voice

so often to be heard in the correspondence with Hofmannsthal, In Strauss,

there is nothing else for a male singer to compare with La Roche’s big

aria or diatribe; this is perhaps the most novel feature of Capriccio. Surely

it is Richard Strauss the anti-modemist who says:

1 preserve all the good things that have been written; the art of our

fathers lies in my trust... Where is the masterpiece today that speaks

to the hearts of the people, in which their souls are seen reflected?

Teannot discover it

Other quotations from this aria deserve attention later,

Six days before Strauss completed the full score he wrote to Krauss:

I'm taking great trouble to ensure that the last scene is especially

beautifully orchestrated for our dear friend! {the soprano Viorica

Ursuleac, Krauss’s mistress and later his wife]. “Therefore the

harps,” as dear old Bruckner used to say about his trombones.

The opera was now known as Capriccio, but the title had not been de-

cided until 6 December 1940 at Krauss’s suggestion after they had dis-

cussed many alternatives. Strauss was still not entirely convinced and

hankered after The Sonnet or The Countess's Sonnet. But Capriccio it be-

came, Itwas Krauss, too, who suggested the subtitle of “conversation piece.”

Now came the question of performances. In spite of his ban on a

performance of Die Liebe der Danae, Strauss does not seem to have

been so adamant about Capriccio. Moreover, he was indebted to Krauss,

who was in favor with the régime. Krauss had been music director of

‘Munich Opera since 1937 and had built up a Strauss repertory with some

fine singers. But since September 1941 he had been artistic director of

the Salzburg Festival and it was there that Strauss wanted Capriccio to be

performed, On 12 October 1941 he wrote to Krauss:

If the festival hall in Salzburg is more intimate than the Hoftheater

in Munich and the acoustics at least good enough for the text to be

well understood (that is unfortunately not the case in Munich), we

would of course have to try it out first — this would be the factor to

outweigh all other considerations. Don’t forget Capriccio is not a

piece with universal audience appeal, atleast not for an audience of

1800 people per evening. It is perhaps a delicacy for cultural con-

168 MICHAEL KENNEDY

noisseurs (musically not very important, in any case not so tasty

that the music will help out if the great public fails to warm to the

libretto). That is why this unusual litle baby has to be presented in

a special cradle and that means the Salzburg Festival! Audiences go

there specially and apply different criteria.

But Krauss won the argument. He wanted Capriccio as the climax of a

Strauss Festival in Munich in the summer of 1942 for which he had

gained Goebbels’s approval. But the festival was postponed because of

transport shortages caused by military requirements and because the

baritone Hans Hotter, who was to sing Olivier, suffered from hay-fever

every June. The Capriccio premiére was fixed for 28 October 1942 in

the Nationaltheater, Munich. Swauss installed himself in the Hotel

Vierjahreszeiten, attended all the rehearsals and played Skat with some

of the singers, including Franz Klarwein and Hotter, until midnight. (They

let him win because they wanted to go to bed.) Ursuleac, who had cre-

ated Arabella and the Commandant’s Wife in Friedenstag and was to

create Danae, sang the Countess, Horst Taubmann was Flamand, Hotter

Olivier, Georg Hann La Roche, Walter Hofermayer the Count, Carl

‘Seydel was Taupe, and Irma Beilke and Franz Klarwein the Italian sing-

ers. The role of Clairon, written for contralto, was re-written by Strauss

for the soprano Hildegarde Ranczak (this, and an alternate version for

Madeleine, is to be found in the Richard-Strauss-Institut in Garmisch),

but today is usually sung by a mezzo-soprano, Hartmann produced it

and the décor was by Rochus Gliese. Strauss described exactly what he

wanted for furniture and lighting. Goebbels did not attend the premiére,

which was given under his patronage. This was a victory for Krauss,

because Strauss was out of favor.

Because of almost nightly air raids on Munich, which began at

about 10pm, it was decided that the performances should start at 7pm so

as to be over by 9.30 and that the opera should be given without an

interval. Hartmann states in his book on the staging of Strauss operas

(see note 1) that Strauss and Krauss had planned for an interval (but the

score when published said “in one act"). It is usual today to have an

interval, Hartmann reverted to this format for the Paris premiére in 1957.

‘The Strauss authority Norman Del Mar calls it “an iniquitous custom,”

but few would agree. Hartmann vividly recalled the atmosphere sur-

rounding those first Munich performances:

Who among the younger generation today can really imagine a great

city like Munich in total darkness, or theater-goers picking their

way through the blacked-out streets with the aid of small torches

giving off a dim blue light through a narrow slit? All this for the

FROM CASTITO CAPRICCIO 189

experience of the Capriccio premiére. They risked being caught in

a heavy air raid, yet their yearning to hear Strauss’s music, their

desire to be part of a festive occasion, and to experience a world of,

beauty beyond the dangers of war led them to overcome all these

material problems.

A further 15 performances were given in 1942-3, with some changes of

cast. Klarwein sometimes sang Flamand and Carl Kronenberg Olivier.

‘The final performance was on 17 June 1943 in honour of Strauss's 79”

birthday a week earlier. This was broadcast and a recording of it has

since been issued. Four months later, the Nationaltheater was destroyed

by bombs. Peiformances of Capriccio followed in Hanover, Darmstadt,

Bielefeld, Dresden, Ziirich, and Vienna. The first Salzburg production

was in 1950, conducted by Karl Bohm, who had hoped to conduct the

world premicre as he had done those of Dic schweigsame Frau in 1935

and of Daphne (dedicated to him) in 1938. The first London perfor-

mance was in 1953 (by a visiting company); in the United States in 1954

(at the Juilliard School of Music); and at Glyndebourne (to which it is

ideally suited) in 1963. Far from being a piece for connoisseurs, Ca-

priccio has entered and remained in the regular international repertory.

Is this a triumph for words or music? The words are brilliant, but it is

the music that has endeared this great opera to so many listeners.

The question has often been asked: how, in 1940 and 1941, with

Europe at war and with tyranny on the march in his own country, could

Strauss have written an opera so far removed from the spirit of the time?

How could he sit at his desk in Garmisch concocting an aesthetic argu-

ment on the supremacy of words or music when the world was engulfed

in suffering and thousands were dying not only on the battlefield but in

concentration camps? If we were to purge the world of works of art,

music, and literature that bore little relation to the times in which they

were created, we would deprive ourselves of many masterpieces.

Strauss’s case 1s complex, as the first part of this essay will have shown.

One answer he himself might have given is that he was a Nietzschean

and believed that art is the one and only justification of life. That is a

philosophy which could not be sustained today, but to a 19% ccntury

man like Strauss it presented no difficulty. I doubt that he would have

put forward the defence, if defence were needed, that his work on Danae

and Capriccio was what has bccn called “inner emigration,” an escape

from reality into one’s creative kingdom.

‘Two principles governed Strauss’s life, and one must accept them

or reject him entirely. The first was the all-consuming obsession with

his own music, the other his passionate love for his family. The number

190 MICHAEL KENNEDY

of performances of his works and the royalties they accrued were of

overwhelming importance to him, not because he wanted to live in a

regal style, but because they provided the security he desired for his

family. It was as simple as that, He had lost a large amount of money in

both world wars when his foreign royalties were frozen or confiscated.

But Strauss’s position vis-a-vis the Nazi régime at this time was far

from simple. In spite of his dismissal in 1935, the Nazis, while keeping

him at arm’s distance, knew that he was still an indispensable interna-

tional asset. Thus, they allowed him to visit London, Paris, Rome, and

elsewhere. But if they needed him, he especially needed them if he was

to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law Alice and her sons. If that meant

conducting under Goebbels’s auspices here and there, it was worth it.

And it was worth it because in November 1938, the time of the

Kristallnacht persecution of the Jews, stormtroopers went to the Garmisch

villa hoping to find and arrest Alice, who had been hidden by friends.

At the same time, the elder grandson Richard, aged 11, on his way to

school, was asked by a stormtrooper “Where is your Jew mother?” and

was taken to the town square to watch Jews being manhandled. His

brother Christian, aged six, was fetched and forced to spit on Jews.

‘Suauss then begun to trade on his position to win some special privi-

leges for Alice, his son Franz (her husband) and their children. In the

spring of 1941 he won limited “Aryan” status regarding education for

the grandsons but nothing for Franz or Alice. At this point, the Gauleiter

of Vienna, Baldur von Schirach, enlisted Strauss’s help in building up

‘Vienna as a cultural capital. Schirach was out of favor with Hitler and

Goebbels and knew that Hitler was unrelenting on “the Jewish ques-

tion.” But he needed Strauss (who owned a villa in Vienna) and gave

him vague promises of protection that, more or less, he kept. In Decem-

ber 1941, Strauss and his family moved to Vienna; thereafter he com-

muted between there and Garmisch as occasion demanded. Schirach’s

reward was the first performance of the Sextet trom Capriccio on 7 May

1942 at a private gathering in his house. During 1942, before Capriccio

was performed, Alice’s grandmother was incarcerated in Theresienstadt con-

centration camp, where she died. Twenty-six of Alice’s relatives also died

inthe camps. In February of that year, Strauss was summoned to Berlin and

subjected to insulting verbal abuse by Goebbels.

These are merely some of the facts of the cat-and-mouse game

played between Strauss and the Nazis from July 1935 to 1944, It was a

game in which Strauss was prepared to sacrifice his good name in order

to protect his nearest and dearest. Who shall blame him? It was against

FROM CASTI TO CAPRICCIO 191

this background that Capriccio was composed. We need to look at some

of La Roche’s aria in this context where he refers to the

vulgar forces our capital city finds diverting... The masks have been

removed, to be sure, but you see caricatures instead of human coun-

tenances! You despise these goings-on, yet you tolerate them! You

make yourselves guilty by your silence.

Perhaps Capriccio is not “escapist.”

It was, though, a success, When a critic wrote that it was a piece

for connoisseurs Strauss, forgetting his own earlier misgivings, wrote to

Krauss quoting La Roche: “Will it not really ‘speak to the heart of the

people’?” He knew it was his testament, the best conclusion to his life’s

work for the theater. “Do you really believe that after Capric-

cio...something better or even just as good could follow?” The last mu-

sic he ever conducted, two months before he died, was the Moonlight

Music. He always knew how to make a good end.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Sunday StudyguideDocument18 pagesSunday StudyguideGata MeeraNo ratings yet

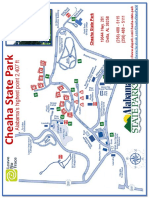

- Cheaha Park MapDocument1 pageCheaha Park MapGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- FS 17Document3 pagesFS 17Gata MeeraNo ratings yet

- ProgramNotes Strauss MetamorphosenDocument3 pagesProgramNotes Strauss MetamorphosenGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- Kefir InstructionsDocument2 pagesKefir InstructionsGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- US05WIU1Document1 pageUS05WIU1Gata MeeraNo ratings yet

- The Yellow DwarfDocument24 pagesThe Yellow DwarfGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- 2019 08 Campus MapDocument1 page2019 08 Campus MapGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- The Hind in The WoodDocument24 pagesThe Hind in The WoodGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- 2020 Ballpark MapDocument1 page2020 Ballpark MapGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- 12 Seitan or Tofu MarinadesDocument2 pages12 Seitan or Tofu MarinadesGata MeeraNo ratings yet

- M. Owen Lee - Love That Colors and Transforms - Die Frau Ohne SchattenDocument8 pagesM. Owen Lee - Love That Colors and Transforms - Die Frau Ohne SchattenGata MeeraNo ratings yet