Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Science and Philosophy - Hobbes

Uploaded by

Franca BorelliniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Science and Philosophy - Hobbes

Uploaded by

Franca BorelliniCopyright:

Available Formats

Science and Philosophy

During the last years of the Renaissance the baroque exuberance of its central phase declined.

The most diverse tendencies contributed to this, Puritan plainness and classical restraint above

all. The reaction against metaphysical excesses also came from the new philosophy and

science, which had already been heralded by Francis Bacon at the beginning of the century.

The seeds of the scientific revolution of the 18th century were sown during the last phase of

the Renaissance. The revolution that Copernicus had started in the 16th century developed so

rapidly and so broadly that physics were transformed together with astronomy. In theoretical

terms this meant that the break with the old Aristotelian idea of the universe was complete. In

practical terms there was a parallel development in the design and manufacture of scientific

instruments.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

The other great philosopher of Renaissance England, also strongly opposed obscure

expressions and elaborate conceits. He was in favour of clear thoughts expressed in clear short

sentences, and of direct statements instead of metaphors. His interest in language and rhetoric

as instruments of social and political power was to be greatly influential well into the 18th

century and later. Unlike Bacon, with his empiricism filled with optimism and enthusiasm,

Hobbes was a decided materialist in philosophy; one of his often quoted statements is: ‘The

universal is corporeal; all that is real is material, and what is not material is not real’. For him,

the soul and its operations had all material causes and man’s sentiments – what pleased or

displeased him – were due to external ‘motions’, or factors. Hobbes held a cynical view of

human nature and society. He believed that the state of nature for man only meant war and

destruction; he is the author of the famous phrase: ‘man is a wolf to man’. He argued that

society was run by two overwhelming motivations: fear (of death, other people, social habits,

and so on) and the desire for power. The ways in which these two concerns operate on society

can be rationally analysed as a mechanism. The work in which Hobbes conducts this analysis is

Leviathan (1651). It takes its name from the biblical sea-monster, or whale, which for Hobbes

symbolises the huge and all-powerful organism that alone can control man’s naturally violent

nature: a strong government. Written at the time of the civil wars, the book reflects Hobbes’

pessimistic view of man and expresses a desire for stable government – a sovereign power,

which does not necessarily have to be the king. In examining society and the history of

mankind Hobbes’s displays a cold detachment not unlike that of Machiavelli, which enables him

to deny man’s inherent goodness. In the absence of a supreme power men fall back to a

brutish state in which they are endlessly at war with each other. This, according to Hobbes, is

the fate of mankind unless the social machine regulates and redeems it. Hobbes’s position is

thus opposed to the theories of the natural goodness of man, especially primitive man living in

a state of nature.

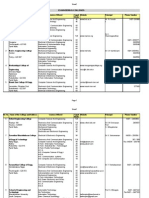

You might also like

- New Zealand Considers Lowering The Voting Age To 16Document3 pagesNew Zealand Considers Lowering The Voting Age To 16Franca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Nov 2021 The British World Heritage Sites XteachxDocument4 pagesNov 2021 The British World Heritage Sites XteachxFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Population Decline Social Justice and The EnvironmentDocument7 pagesPopulation Decline Social Justice and The EnvironmentFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Formal Debate Vocabulary ListDocument2 pagesFormal Debate Vocabulary Listvandana61No ratings yet

- Scheda Movimento LetterarioDocument3 pagesScheda Movimento LetterarioFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Thomas MoreDocument1 pageThomas MoreFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Formal Debate Phrases and StrategiesDocument4 pagesFormal Debate Phrases and StrategiesFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Revised TKTCLILlesson Plan TemplateDocument2 pagesRevised TKTCLILlesson Plan TemplateFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Wyatt and SurreyDocument2 pagesWyatt and SurreyFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Scheda Movimento LetterarioDocument3 pagesScheda Movimento LetterarioFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- The Cult of RuinsDocument1 pageThe Cult of RuinsFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Could You Be Addicted To The Internet - Everyday HealthDocument18 pagesCould You Be Addicted To The Internet - Everyday HealthFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Kazuo Ishiguro (BDocument2 pagesKazuo Ishiguro (BFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Kingsley Amis (1922-1995)Document2 pagesKingsley Amis (1922-1995)Franca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Thom Gunn (1929-2004)Document3 pagesThom Gunn (1929-2004)Franca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- J BallardDocument2 pagesJ BallardFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Ann RadcliffeDocument1 pageAnn RadcliffeFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Pre-Intermediate / Intermediate: Level 1Document4 pagesPre-Intermediate / Intermediate: Level 1Franca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824)Document6 pagesGeorge Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824)Franca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Edmund BurkeDocument1 pageEdmund BurkeFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- A Lack of Order in The Floating Object RoomGeorge Saunders - Hunger Mountain ReviewDocument5 pagesA Lack of Order in The Floating Object RoomGeorge Saunders - Hunger Mountain ReviewFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying - What Is It and How To Stop It - UNICEFDocument23 pagesCyberbullying - What Is It and How To Stop It - UNICEFFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Alliterative PoemsDocument1 pageAlliterative PoemsFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Horace WalpoleDocument1 pageHorace WalpoleFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Could You Be Addicted To The Internet - Everyday HealthDocument18 pagesCould You Be Addicted To The Internet - Everyday HealthFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Advanced: Level 3Document5 pagesAdvanced: Level 3peteNo ratings yet

- Mappa Past S - and CDocument3 pagesMappa Past S - and CFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter SampleDocument13 pagesHarry Potter SampleFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Meena KandasamyDocument7 pagesMeena KandasamyFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Meaning of Research DesignDocument24 pagesMeaning of Research Designvaqas HussainNo ratings yet

- ADEC - Modern Private School 2015 2016Document20 pagesADEC - Modern Private School 2015 2016Edarabia.comNo ratings yet

- Environmental Chemistry Course ObjectivesDocument2 pagesEnvironmental Chemistry Course ObjectivesSajedur Rahman MishukNo ratings yet

- Marianna Galingging ResumeDocument1 pageMarianna Galingging ResumeMariana GalinggingNo ratings yet

- Oxford Bibliographies Cognitive Dissonance TheoryDocument3 pagesOxford Bibliographies Cognitive Dissonance TheoryOussama ThrNo ratings yet

- What Is EngineeringDocument14 pagesWhat Is EngineeringBrayan MosqueraNo ratings yet

- Queuing Theory To Reduce Waiting Time in Automatic Teller Machine (ATM)Document9 pagesQueuing Theory To Reduce Waiting Time in Automatic Teller Machine (ATM)IJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Reseach PaperDocument6 pagesReseach PaperNamrah KhatriNo ratings yet

- Leibniz BiographyDocument5 pagesLeibniz Biography412lightNo ratings yet

- Physics WaveDocument6 pagesPhysics WaveRevolver RTzNo ratings yet

- Crossword Puzzle Maker - Final PuzzleDocument2 pagesCrossword Puzzle Maker - Final PuzzleCy YoungNo ratings yet

- 4114939494Document2 pages4114939494Uzair AhmadNo ratings yet

- Legal Persuasion TechniquesDocument47 pagesLegal Persuasion TechniquesNitish Verghese100% (1)

- Bio-Topical GoaDocument4 pagesBio-Topical Goachreod99No ratings yet

- Good Laboratory Practice. Part 2. Recording and Retaining Raw DataDocument4 pagesGood Laboratory Practice. Part 2. Recording and Retaining Raw Dataanonim 2123No ratings yet

- Hard Reading - Learning From Science Fiction - Tom ShippeyDocument352 pagesHard Reading - Learning From Science Fiction - Tom ShippeyRaúl III100% (3)

- 1996 Giere-Richardson OriginsofLogicalEmpiricism PDFDocument24 pages1996 Giere-Richardson OriginsofLogicalEmpiricism PDFPablo MelognoNo ratings yet

- Facets of DataDocument22 pagesFacets of DataPrashant SahuNo ratings yet

- Engineering CollegesDocument5 pagesEngineering Collegeslakshmi_priya53No ratings yet

- J.C Bose Memorial and InnovationDocument18 pagesJ.C Bose Memorial and InnovationS.M. Rezvi Rezoan ShafiNo ratings yet

- G1. Chapter 1234 ReferenceDocument36 pagesG1. Chapter 1234 ReferenceJoyce Ann Rivera ComingkingNo ratings yet

- Unit-Ii Sample and Sampling DesignDocument51 pagesUnit-Ii Sample and Sampling Designtheanuuradha1993gmaiNo ratings yet

- Edu Edu0000214Document20 pagesEdu Edu0000214Jeric Espinosa CabugNo ratings yet

- OutputDocument2 pagesOutputMelano ArjayNo ratings yet

- The Living WorldDocument19 pagesThe Living WorldYoginiben PatelNo ratings yet

- Learning From Others and Reviewing The Literature Lesson 1: Selecting Relevant LiteratureDocument8 pagesLearning From Others and Reviewing The Literature Lesson 1: Selecting Relevant LiteratureLINDSAY PALAGANASNo ratings yet

- JADC2: Getting Down To Work: Ndia 2023 Human Systems ConferenceDocument23 pagesJADC2: Getting Down To Work: Ndia 2023 Human Systems Conferencelfx160219No ratings yet

- Engineering Europe's Next Generation of Innovators and Problem-SolversDocument11 pagesEngineering Europe's Next Generation of Innovators and Problem-Solversالواثقة باللهNo ratings yet

- DLL Isaac Week 1 August 29 September 01Document9 pagesDLL Isaac Week 1 August 29 September 01Marvin Jay Ignacio MamingNo ratings yet

- A Study On Awairness of E-Banking ServicesDocument5 pagesA Study On Awairness of E-Banking ServicesGaurav JagtapNo ratings yet